Abstract

Objective: Interventional pain management has been recognized over the last couple of decades for treating chronic-pain syndromes. Acupuncture is a nonpharmacologic therapeutic option for pain management and may be an option for different patients with contraindications for interventional pain management. This review explores this options.

Method: This limited review examines the role of acupuncture for managing head-and-neck pain and lower-back pain, according to interventional pain management.

Conclusions: Acupuncture at various points, corresponding to the stellate ganglion, which is ST 10 Shuitu, and corresponding to the splanchnic nerve and the facet joint of the lumbar vertebra—which are Ex-B2 paravertebra—can be applied for pain management in the head-and-neck area and in the lower-back area. According to various research findings, acupuncture is effective and safe for reducing pain in the head and neck area, as well as in the lower back.

Keywords: acupuncture, interventional pain management, head-and-neck pain, lower-back pain

Introduction

For treating chronic-pain syndromes, with interventional pain management has been recognized in the past 2 decades. The most important aim of pain medicine is to use a specific therapy—conservative and/or interventional—for the right patient at the right time. Therefore, treatment selection should be made according to the clinical diagnoses of patients.1 Interventional pain management has developed further and involves multiple disciplines. An example is the guideline for interventional pain management used for chronic lower-back pain, which uses facet-joint, trigger-point, sacroiliac-joint, and epidural injections.2 Moreover, interventional pain management is also used with numerous modalities to guide injection targets, with such imaging as ultrasound and fluoroscopy.3 However, interventional pain management has some contraindications; thus, it cannot be applied to all patients.

Acupuncture has been recognized as a nonpharmacologic therapeutic option for pain management. Acupuncture has a variety of modalities for pain management, such as manual acupuncture, electroacupuncture (EA), laser acupuncture, pharmacoacupuncture, and thread embedment. Considering the efficacy of acupuncture that can be used to address different types of pain,4 acupuncture may be an option for different patients who have contraindications for interventional pain management. The locations of certain acupuncture points correspond to the locations of interventional pain management targets. This limited review examines the role of acupuncture for treating head-and-neck and lower-back pain according to interventional pain management protocols.

Acupuncture For Head-and-Neck Pain With Stellate-Ganglion Block

Anatomy of a Stellate Ganglion

Stellate ganglions are irregularly formed ganglions that occur in 80% of the population This kind of ganglion constitutes the cervical-sympathetic chain as a fusion of the inferior cervical and the first thoracic sympathetic ganglion. A stellate ganglion lies anterior to the neck of the first costa inferior to the transverse process of the seventh cervical vertebra; receives preganglionic supplies from the first and second thoracic segments; and, therefore, supplies the head-and-neck region innervations.5,6

A stellate-ganglion block or lower cervical-sympathetic block has been advocated for diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic purposes in a variety of conditions. Although multiple techniques are advocated for performing this block, fluoroscopically guided sympathetic blocks are more appropriate. Complications of a stellate-ganglion-block include those related to the technique, infections, and pharmacologic complications related to the drugs utilized. A cervical-sympathetic or stellate-ganglion block is a very commonly performed procedure. If performed correctly, this block can provide good, therapeutic, prognostic, and diagnostic results.7

In a 2016 study by Ghai, et al., 20 patients suffering from chronic pain of the upper extremities, head, and, neck that did not respond to conservative treatments, had decreased pain intensity (P < 0.05) 30 minutes after receiving a stellate ganglion block, and the analgesic effect was sustained until the third month of follow-up.8

Acupuncture in ST10 Shuitu Points

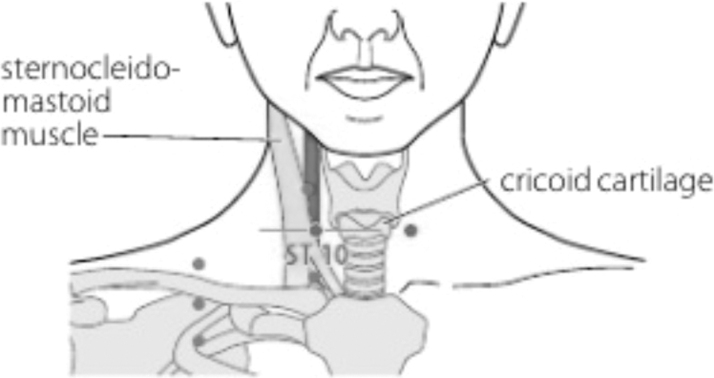

ST10 Shuitu is an acupuncture point located on the anterior neck region, at the same level with an inferior border of thyroid cartilage, just anterior to the border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 1).9 This point is innervated by the cervical branch of the facial nerve, the sympathetic trunk, and the descending branch of the hypoglossal and vagus nerves.10 By locating ST 10 point that corresponds to the stellate ganglion, acupuncture stimulation at ST 10 can be developed to block the stellate ganglion.

FIG. 1.

Location of ST 10 Shuitu point.9 Source: WHO standard acupuncture point locations, 2010.

Needling ST 10 Shuitu can be performed by instructing the patient to turn the head contralaterally. While palpating the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the level of inferior border of the thyroid cartilage, 1 finger marks the pulsating carotid artery for safety. Needling is performed anterior to the finger, perpendicularly to the skin, turned slightly superior to the medial, and pushed further for 10–15 mm. Lifting, thrusting, and rotating may be performed to induce sensations in the face, and then retained for 30 minutes.11

Acupuncture for Lower-Back Pain with Splanchnic-Nerve Block and Vertebral Facet-Joint BLOCK

Anatomy of the Splanchnic Nerves

The splanchnic nerves are bilateral visceral autonomic nerves. They include the thoracic splanchnic nerves (greater, lesser, and least or lowest), lumbar splanchnic nerve, sacral splanchnic nerve, and pelvic splanchnic nerve (erigentis nerve). All splanchnic nerves have preganglionic (presynaptic) sympathetic fibers, except for the pelvic splanchnic nerves, which have preganglionic parasympathetic fibers. These nerves have connections to the celiac plexus, aorta, mesenteric and hypogastric areas, and pelvis; and control the function of the gut and pelvic organs. These splanchnic nerves are predominantly constituted of motor-nerve fibers leading to the internal organs (visceral-efferent fibers) and sensory-nerve fibers; as well as pain signals originating from these organs (visceral-afferent fibers).12, 13

The greater splanchnic nerve is in the highest position of the 3 nerves and receives branches from the T-5–T-8 thoracic-sympathetic ganglia, the lesser splanchnic nerve lies below the greater nerve and receives branches from the T-9 and T-10 sympathetic ganglia, and the least splanchnic nerve is the lowest nerve receiving branches from the 11th thoracic and/or 12th thoracic ganglion.12,13

The lumbar-splanchnic nerve emerges from the upper 2 ganglia of the lumbar part of the sympathetic chain (L-1 and L-2). The sacral-splanchnic nerves, on each side, connect the sacral part of the sympathetic trunk (1st sacral ganglion) to the inferior hypogastric (pelvic) plexus. The lumbar splanchic nerve's preganglionic sympathetic fibers ascend from the inferior to the superior hypogastric plexuses; then go to the aorta and inferior mesenteric plexuses (where they relay); then go to innervate the hindgut. From each pelvic plexus, sacral splanchnic fibers also supply the pelvic vessels and organs. Delicate fibers emerge from the sacral roots, S-2, S-3, and probably S-4, to form the pelvic splanchnic nerves on each side (or nervus erigentis) arising from the ventral primary rami of the second, third, and often the fourth sacral nerves, providing preganglionic parasympathetic innervation to the hindgut.13

Anatomy of the Vertebral Facet Joint

The facet joints are the synovial joints of the spine that can be involved in various processes. The facet joint is formed by the superior and inferior articular processes of 2 adjacent vertebrae. The facet joint is a considered to be a synovial joint—due to its fibrous capsule, which encloses the articulation of bone and cartilage—and is sustained by the periosteum. This joint also contains synovial fluid. The facet joint is located between the pedicle and lamina of the same vertebra and forms an articular pillar that provides total structural stability of the vertebra. The functional unit of the vertebral column consists of 2 connected vertebral bodies, an intervertebral disc, and two 2 joints. This unit is called a motion segment. The posterior segment of the spine guides its movement, with the type of movement being determined by the facet-articulation plane. The coronal orientation of the joint minimalizes extension but sustains rotation, whereas the rotational side orientation of the lumbar articulation minimalizes rotation.9 The posterior segment contains a complex of posterior ligaments that play an important role in stabilizing this area. This complex consists of the supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, articular-facet capsule, and ligamentum flavum. The sensory nerves of this joint are the medial branches of the ramus of the spine.9,14

Various abnormalities can occur in the facet joints, such as effusions, cysts, septic arthritis, tumors, etc.14 However, the most common problem is facet-joint syndrome. Facet-joint syndrome, is a condition in which this joint is the source of pain. Chronic low-back pain often results from facet-joint disorders, with a prevalence of 15%–41%.15

The most-common cause of facet-joint syndrome is degeneration of the spine, also known as spondylosis. Joint degeneration that occurs with age and abnormal body mechanisms is known as osteoarthritis (OA). The pathophysiology of OA is not understood fully. It is a complex condition involving various cytokines and proteolytic enzymes. Other causes of facet-joint disease include trauma caused by injury or sports activities. Inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, can also cause inflammation of the synovium.

Subluxation of the facet joints due to spondylolisthesis can also contribute to the development of facet-joint syndrome. Patients with this syndrome show signs of cartilage erosion and inflammation, which can cause pain. The body will also undergo some physical changes in response to this process. Ligaments, such as the ligamentum flavum, can become thickened and hypertrophic. The formation of new bone around a joint can occur with the development of osteophytes or “bone spurs.” There may also be an increase in subchondral bone volume with hypomineralization.15 On magnetic resonance imaging, articular-cartilage thinning, osteophytes, ligament thickening, and joint effusion can be found.9 Spondylolisthesis caused by degeneration is often caused by OA of the facet joints, and usually occurs in L-4–L-5. Spondylolisthesis that appears in a younger patient (ages30–40) can be caused by congenital abnormalities, stress, or fractures.15

Acupuncture in Ex-B2 Paravertebral Points

Ex-B2 paravertebral points (Huato Jiaji) are 17 pairs of points on the back of the body, located at 0.5 cun lateral to the lower border of the spinous processes, close to the spinal-facet joints, comprising 12 pairs of thoracic points (Thoracic Jiaji) between T-1 and T-12, and 5 pairs of waist points (Back Jiaji) between L-1 and L-5 (Fig 2).11 In other references, an Ex-B2 point can be located 0.5 cun lateral from the midline from C-1 to L-5.16,17 Among others are cervical, thoracic (T-1–T-10), thoraco–lumbar (T-11–L-2), and lumbar compartment or psoas areas (L-2–L-5).17

FIG. 2.

Location of Ex-B2 Jiaji points.11 Source: Atlas of Acupuncture. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2008.

One can determine an Ex-B2 point location, according which one is desired, then determine the location of the spinous process and determine the location of the 0.5-cun point on the lower lateral border. Then one can puncture 0. 5–1 cun vertically or at a medial angle to the spine, up to 1.5 cun in the lumbar area. The purpose of puncturing this area is to stimulate local nerve roots. Therefore, the insertion angle must be adjusted according to the patient's anatomy. After inducing De Qi, manual needle stimulation can be stopped and can be continued with electrostimulation.11

Acupuncture has many advantages, including curative effects, no side-effects, simple manipulation, and relatively low cost. Acupuncture is 90% effective for treating low back-pain. Choice of local acupoints, with an Ashi point as the main acupuncture point includes remote acupuncture points; and such additional main acupuncture points as BL25 Dachangshu, Ex-B2 Jiaji, BL 23Shenshu, BL40 Weizhong.18

Acupuncture stimulation at Ex-B2 provides reduction in low-back pain with stimulation of the skin and muscle tissue around the vertebrae supplied by the posterior ramus of the spinal cord and causes changes in the sciatic nerve and blood flow mediated by this nerve reflex response. Clinically, acupuncture stimulation on Ex-B2 is the first choice because it is easy, safe, and effective. However, if the results are ineffective, treatment with EA stimulation of the pudendal nerve can be attempted.19

Needling techniques in Ex-B2 paravertebral points include Xiang Wei Needling, Seven Needling, Four Flowers Needling, and Five Needling. Xiang Wei Needling involves using a needle tip inserted in the direction or “tail,” subcutaneously at the midline of the spine, into the appropriate 6-cun acupuncture point. The Seven Needling technique involves first inserting a needle into the Yaoshu and then pricking the site at an upward angle under the skin. The second needle is inserted into the spinous process at an upward angle. Ultimately, all seven needles are inserted at the same distance at the posterior midline. The sensations of anesthesia, pain, numbness, and prominence in the local area may be felt. The Four Flowered needles are inserted at an angle (slightly downward and inward) from Geshu and Dashu at an angle of 45° to the spine 0.5–0.8 cun until anesthesia is felt. Five Needling Flowers inserted at an angle from Xinshu and Geshu at an angle of 45° into the spinal column at 0.5–0.8 cun. Another needle is inserted at an angle upward into the Lingtai at the same depth.20

Discussion

As a cervical-sympathetic ganglion, as stellate ganglion supplies sympathetic innervation to the head-and-neck region, upper extremities, and chest. A stellate ganglion block—a procedure used to block sympathetic nerves—can either be diagnostic or therapeutic. This is performed with the patient under sedation, via fluoroscopy, computed tomography, or ultrasound guidance, using such local anesthesia as bupivacaine. The indications include pain in the head, neck, upper extremities, and chest (most commonly complex regional pain syndrome); vascular disorders, local complications following mastectomy; postherpetic neuralgia; hearing disorders; hyperhidrosis of an upper extremity; cardiac arrhythmias; hot flashes; and post-traumatic stress disorder.6,7

Many studies on acupuncture as a nonpharmacologic treatment for pain management have been performed with various modalities. A clinical trial was conducted on the use of the ST 10 Shuitu point corresponding to the middle cervical ganglion as acupuncture therapy. A 2001study, by Huang et al., which examined the effect of acupuncture therapy on migraine, showed a significant reduction in pain intensity in a treatment group, compared to a control group, with a P-value <0.01. There was a significant decrease in the frequency of attacks, with better results in the treatment group than in the control group. There was a change in rheoencephalogram results, which returned to normal in 80 patients (81.6%) in the treatment arm and 30 patients (65.3%) in the control arm. Outcomes of improvement in the treated group were greater than in the control group. Overall, the effective rate of 96.9% in the treatment group was better than 89.1% in the control group with P < 0.05.21

Splanchnic-nerve and facet-joint block techniques have also been studied for management of low-back pain. Li et al. used warm acupuncture on 8 points bilaterally, as well as BL 23, BL 25, BL 54, and Ex-B2 15/16 unilaterally on the affected side of a patient with low-back pain caused by lumbar-disk herniation. Combining acupuncture and infrared thermal therapy can improve blood circulation, increase cell phagocytosis, induce strong anti-inflammation in the surrounding nerve area, and provide nonspecific acupuncture effects on endogenous opioids.22

In 2003, Meng et al. conducted a study of a combination of acupuncture and medical therapy, compared to medical therapy alone for chronic low-back pain. Stimulation was induced at GV 3, GV 4, BL 23, BL 24, BL 25, BL 36, BL 37, BL 40, and BL 54 twice per week for a total of 5 weeks. Better pain reduction occurred in the intervention group, compared to the medication-alone group (P < 0.001).23

In 2006, comparing a wait-list group with an acupuncture-treated group, Brinkhaus et al. performed acupuncture in at least 4 points in the acupuncture group, choosing points from BL 20 to BL 34, BL 50 to BL 54, GB 30, GV 3, GV 4, GV 5, GV 6, Ex-B2, and M-BW 25 for chronic back pain, twice per week in the first 4 weeks, then once per week for 4 weeks. The acupuncture group had better pain relief than the wait-list group.24

A 2007 study by Kennedy et al. compared the effects of verum acupuncture and a nonpenetrating sham-acupuncture control condition in patients with nonspecific, acute low-back pain. In the verum acupuncture group, stimulation was induced at 8–13 points, selected from GV 3, GV 4, BL 23, BL 25, GB 29, GB 30, GB 31, GB 34, BL 36, BL 37, BL 40, BL 56, BL 60 at a minimum of 3 times and a maximum of 12 times within 4–6 weeks. There was a significant reduction of pain in the verum acupuncture group, compared to the nonpenetrating sham-acupuncture group at a 3-month follow-up.25

Based on the findings of the abovementioned studies, it can be concluded that acupuncture can produce an analgesic effect in cases of head-and-neck pain and low-back pain. Acupuncture therapy for patients with head-and-neck pain can be performed by puncturing the ST 10 Shuitu points, according to the location of the stellate ganglion. For cases of low-back pain puncturing at the Ex-B2 paravertebral point can be performed.

Conclusions

At various points, acupuncture, corresponding to the stellate ganglion, which is ST 10 Shuitu, and corresponding to the splanchnic nerves and the facet joints of the lumbar vertebra, which are Ex-B2 paravertebral points, can be applied to interventional pain management according to the area the acupuncture is intended to innervate. According to research, acupuncture at various points has been proven to be effective and safe for reducing pain in the head-and-neck area as well as in the lower-back area.

Author Disclosure Statement

No financial conflicts of interest exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this paper.

References

- 1. Imani F, Rahimzadeh P. Interventional pain management according to evidence-based medicine. Anesth Pain Med. 2012;1(4):235–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Medical Policy Interventional Pain Management. Injections: Sacroiliac, Epidural Steroid, Facet and Trigger Point. 2020. Online document at: www.paramounthealthcare.com/assets/documents/medicalpolicy/PG0354_Invasive_Procedures_for_Back_Pain.pdf Accessed May 27, 2020.

- 3. Narouze SN. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures in pain management: Evidence-based medicine. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(suppl1):S55–S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA, Lewith G, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: Update of an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Pain. 2018;19(5):455–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Standring S, ed. Gray's Anatomy [e-book]: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 41st ed. China: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elias M. Cervical sympathetic and stellate ganglion blocks. Pain Physician. 2000;3(3):294–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gunduz OH, Kenis-Coskun O. Ganglion blocks as a treatment of pain: Current perspectives. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2815–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ghai A, Kaushik T, Kundu ZS, Wadhera S, Wadhera R. Evaluation of new approach to ultrasound guided stellate ganglion block. Saudi J Anaesth. 2016;10(2):161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lim S. WHO standard acupuncture point locations. Evid-Based Complement Alternat Med. 2010;7(2):167–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhu B, Wang H. Meridians and Acupoints. Philadelphia: Singing Dragon; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Focks C. E-Book-Atlas of Acupuncture. Muchen: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Naidoo N, Partab P, Pather N, Moodley J, Singh B, Satyapal K. Thoracic splanchnic nerves: Implications for splanchnic denervation. J Anat. 2001;199(5):585–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haroun H. Clinical anatomy of the splanchnic nerves. MOJ Anat Physiol. 2018;5(2):87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Almeer G, Azzopardi C, Kho J, Gupta H, James S, Botchu R. Anatomy and pathology of facet joint. J Orthop 2020;22(7):109–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Curtis L, Shah N, Padalia D. Facet Joint Disease [internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robinson NG. Interactive Medical Acupuncture Anatomy. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eid HE. Paravertebral block: An overview. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2009;20(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yan LB. Acupuncture treatment for low back pain in China. Japan Acupunct Moxib. 2010;6(1):61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Inoue M, Kitakoji H, Yano T, Ishizaki N, Itoi M, Katsumi Y. Acupuncture treatment for low back pain and lower limb symptoms—the relation between acupuncture or electroacupuncture stimulation and sciatic nerve blood flow. Evid-Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008;5(2):133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yan L. Manipulation and Acu-esthesia: Diagrams of Acupuncture [Chinese–English ed]. Shanghai: Scientific and Technical Publishers; 2001:133–135. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qingwen H, Reixia W. Clinical study on treatment of migraine with acupuncture at Shuitu point. Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion 2001;10. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li T, Wang S, Zhang S, et al. Evaluation of clinical efficacy of silver-needle warm acupuncture in treating adults with acute low back pain due to lumbosacral disc herniation: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meng C, Wang D, Ngeow J, Lao L, Peterson M, Paget S. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain in older patients: A randomized, controlled trial. Rheumatology. 2003;42(12):1508–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brinkhaus B, Witt CM, Jena S, et al. Acupuncture in patients with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Arch.Intern.Med. 2006;166(4):450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kennedy S, Baxter G, Kerr D, Bradbury I, Park J, McDonough S. Acupuncture for acute non-specific low back pain: A pilot randomised non-penetrating sham controlled trial. Complement. Ther Med. 2008;16(3):139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]