Abstract

We have characterized RNA polymerase II complexes halted from +16 to +49 on two templates which differ in the initial 20 nucleotides (nt) of the transcribed region. On a template with a purine-rich initial transcript, most complexes halted between +20 and +32 become arrested and cannot resume RNA synthesis without the SII elongation factor. These arrested complexes all translocate upstream to the same location, such that about 12 to 13 bases of RNA remain in each of the complexes after SII-mediated transcript cleavage. Much less arrest is observed over this same region with a second template in which the initially transcribed region is pyrimidine rich, but those complexes which do arrest on the second template also translocate upstream to the same location observed with the first template. Complexes stalled at +16 to +18 on either template do not become arrested. Complexes stalled at several locations downstream of +35 become partially arrested, but these more promoter-distal arrested complexes translocate upstream by less than 10 nt; that is, they do not translocate to a common, far-upstream location. Kinetic studies with nonlimiting levels of nucleoside triphosphates reveal strong pausing between +20 and +30 on both templates. These results indicate that promoter clearance by RNA polymerase II is at least a two-step process: a preclearance escape phase extending up to about +18 followed by an unstable clearance phase which extends over the formation of 9 to 17 more bonds. Polymerases halted during the clearance phase translocate upstream to the preclearance location and arrest in at least one sequence context.

It is now appreciated that control of transcription often occurs at steps after the assembly of the preinitiation complex (reviewed in references 23, 27, 35, and 44). In particular, a number of transcription units have been described in which an RNA polymerase is paused from 20 to 40 nucleotides (nt) downstream of the transcription start site (reviewed in reference 24). The mechanistic basis for the temporary halting of polymerases at these promoter-proximal locations has not been described.

Promoter-proximal pausing occurs at the transition from the initiation to the elongation phase of transcription. It is therefore reasonable to ask whether such pausing is functionally associated with this transition. For both Escherichia coli RNA polymerase and RNA polymerase II, the continued elongation competence of the transcription complex is thought to be primarily determined by the RNA-DNA hybrid within the transcription bubble (15, 18, 42) and the interaction of a portion of polymerase (the sliding clamp) with the segment of DNA immediately downstream of the bubble (28, 30; see also reference 39). When the advancing RNA polymerase reaches a template region where one or both of these interactions are weak, such as locations which encode long stretches of U in the transcript, the polymerase slides upstream along the template to establish more favorable interactions. The upstream translocation of the transcription bubble displaces the 3′ end of the RNA from the active site of the polymerase, resulting in transcriptional arrest (2, 16, 17, 31). Arrested polymerases retain their transcripts but cannot resume RNA synthesis unless the upstream translocation is reversed or the transcript is cleaved at the active site (3, 9, 25, 32, 36, 38, 43). Either of these events realigns the 3′ end with the catalytic center and allows transcription to continue.

RNA polymerases stalled in the promoter-proximal region resemble arrested complexes in that they retain their transcripts but are unable to continue transcription. However, no common sequence elements that might induce arrest, such as A-rich template strand segments, have been described within the initially transcribed regions of genes which bear stalled polymerases. Footprinting studies with both E. coli RNA polymerase (16, 20, 29) and RNA polymerase II (40) halted 20 to 30 nt downstream of the transcription start site have often revealed strongly upstream-translocated footprints. This is consistent with the possibility that newly initiated RNA polymerases might generally be prone to arrest. However, somewhat surprisingly, not all promoter-proximal RNA polymerase II complexes with upstream-translocated footprints are arrested (40). Thus, the relationship of transcript length, transcript sequence, and elongation competence for promoter-proximal transcription complexes is not well understood.

In this paper we present the characterization of a set of RNA polymerase II complexes paused from 16 to 49 bases downstream of the transcription start site, using templates with two completely different initially transcribed sequences. RNA polymerase II passes through several functionally distinct states during transcription in this region. Up to about position +20, the paused complexes remain fully elongation competent. This is followed by a clearance phase that may continue as far as 32 bases downstream of the transcription start site. During this stage, halted complexes translocate upstream, thereby placing the RNA polymerase over the initiation site. Interestingly, this translocation results primarily in transcriptional arrest in only one of the two sequence contexts. After clearance is achieved, the final elongation state may not be attained until 15 more bases are added to the nascent RNA. Thus, temporarily halting RNA synthesis during the initial stages of transcript elongation can leave RNA polymerase II in danger of arrest, depending on the exact transcript length and sequence. This tendency to arrest may also be observed as transient pausing during free-running transcription reactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Ultrapure nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) and deoxynucleoside triphosphates were obtained from Pharmacia Biotechnology, 32P-labeled NTPs were from NEN, Deep Vent DNA polymerase and restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs, and streptavidin-coated magnetic beads were from Promega Biotech.

Plasmids.

All plasmids used in this study contained the adenovirus major late promoter. The pML20-42 and pML20-46 plasmids were described previously (40). The plasmid referred to here as pML20-23like is actually the second in a series of plasmids of this type and will be referred to elsewhere as pML20-23like2 (A. Újvári and D. S. Luse, submitted for publication). It was constructed by digesting the pML20-42 template with BssHII and StuI at positions −13 and +25 and replacing this segment with a synthetic fragment. The differences between the two templates are shown in Fig. 1; all sequence upstream of −3 is identical for the two promoters. The clone was verified by DNA sequencing.

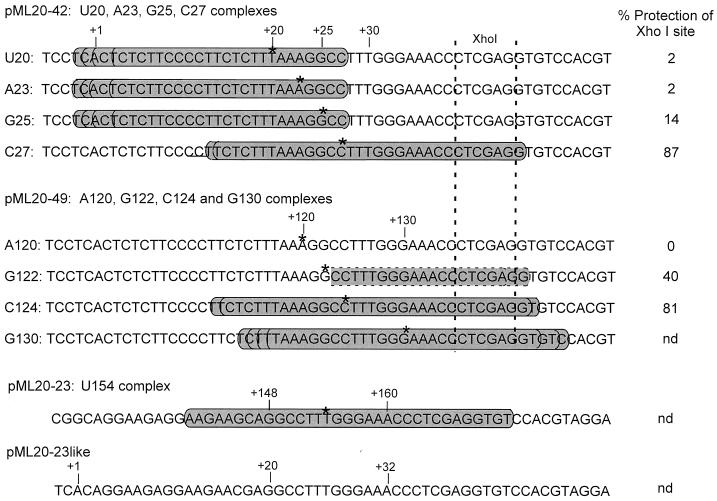

FIG. 1.

Sequences of templates used in this study; summary of nuclease protection results for transcription complexes on the templates. The asterisks show the locations of the 3′ ends of the RNAs, and the shaded ovals indicate the regions protected from attack by exoIII for the complex in question. The pML20-42 and pML20-49 templates and associated exoIII footprints have been described previously (40). Each of these templates contains an XhoI restriction site as shown. The percent protection of this site by the indicated complexes is given by the value in the column at the right; these values were determined as described in Materials and Methods (nd, not determined). The pML20-23 template and the exoIII footprint of the U154 complex have been described previously (39). The pML20-23like template was constructed as described in Materials and Methods.

Template preparation for in vitro transcription reactions.

Linear DNA templates were made by PCR using the forward primer 5′-GGCATCAAGGAAGGTGATTG-3′ (biotinylated at the 5′ end) and the reverse primer 5′-CAGTGCCAAGCTTGCATG-3 (a HindIII site is underlined). This amplified a 190-bp segment of the template with the transcription start site 96 bp downstream of the biotinylated end. After purification using the Concert clean up kit (BRL) and digestion with HindIII to reduce transcription arrest before the end of the template (12), the template DNA was finally purified by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation.

In vitro transcription reaction on attached templates.

Biotinylated template DNA was immobilized on streptavidin-coated magnetic beads by incubation of 15 pmol of template with 220 ng of beads (1 mg of beads/ml of suspension; 1 mg of beads contains ≈1 nmol of streptavidin protein) in 100 μl of BC100 (20 mM Tris, pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol, and 0.2 mM EDTA) for 10 min at room temperature. Preinitiation complexes were assembled basically as described for free template DNAs (39). Template DNA (approximately 1 μg) immobilized on beads was magnetically concentrated and resuspended in 15 μl of water; the final reaction volume of 50 μl contained 50% HeLa cell nuclear extract, 70 mM KCl, and 8 mM MgCl2. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 25 min. Beads from each reaction were washed twice in 150 μl of BC100 and finally resuspended in 35 μl of BC100. On pML20-42 or pML20-46 templates, RNA polymerases were advanced to U20 by incubation at 30°C for 5 min in the presence of 2 mM ApC, 40 μM dATP, 20 μM UTP, and 1 μM [α-32P]CTP in a final volume of 50 μl, followed by further incubation at the same temperature for 3 to 4 min in the presence of 20 μM nonlabeled CTP. On the pML20-23like template, polymerases were advanced to A16 using the same procedure, except the initial 5-min incubation contained 2 mM ApC, 40 μM ATP, and 1 μM [α-32P]GTP, followed by addition of 20 μM GTP. Complexes attached to beads were magnetically concentrated followed by immediate resuspension in 150 μl of wash buffer (30 mM Tris, pH 7.9, 62.5 mM KCl, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 8 mM MgCl2, and 10% glycerol) containing 1% Sarkosyl and incubation at room temperature for 2 to 5 min. The beads were rinsed three times with 150 μl of ice-cold wash buffer without Sarkosyl, resuspended in 100 to 150 μl of the same buffer, and then incubated for 2 to 5 min at room temperature with the required subset of NTPs to advance the RNA polymerases to the next desired position downstream. On pML20-42 and -46 templates, 10 μM NTPs was used, and on the pML20-23like template, 100 μM NTPs was added. The higher NTP concentration on the pML20-23 template was dictated by the greater tendency of complexes to arrest on this template. The beads were washed four times with 150 μl of wash buffer after each walking step to remove free NTPs. To determine the extent of arrest, 10-μl aliquots of halted complexes were preincubated at 37°C for 3 min before chase at 37°C for 3 min with 200 μM (each) NTP.

The reactions were stopped by addition of an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:24:1). RNAs were ethanol precipitated and resolved on either 13% acrylamide gels (19:1 acrylamide-bisacrylamide) or 25% acrylamide gels with 3% bisacrylamide; all gels contained 7 M urea. The gels were imaged, and individual bands were quantified with a PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). RNA length markers were made by partial resection of the transcript of a particular halted complex in the presence of 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate at 37°C for 2, 4, and 8 min.

SII treatment.

Recombinant human elongation factor SII was purified as described previously (45). The SII stock used in this study was stored at 1.27 mg/ml at −70°C and was not subjected to more than two cycles of freezing and thawing; 0.5 μl of this SII preparation, when added to a standard 30-μl transcription reaction mixture and incubated for 5 min at 37°C, was able to restart all of the arrested RNA polymerases on the histone H3.3 gene arrest site in the pML20-30 plasmid (39). All complexes used for SII analyses were preincubated at 37°C for 3 min. For the study of SII cleavage in stalled complexes, 1.25 μl of SII was added to a 50-μl transcription reaction mixture, and the reaction was continued at 37°C; 10-μl samples were withdrawn at the times indicated in the figures. For chases in the presence of SII, 9 μl of the halted complexes was added to 1 μl of 2 mM NTPs and 0.25 μl of SII, and the reaction was continued at 37°C for the times indicated in the figures. All reactions were stopped by equal volumes of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:24:1). Some samples from the 8-min time points were dried after purification, resuspended in 50 μl of water, and incubated with 1 U of calf intestine phosphatase (CIP) at 30°C for 10 min.

Protection of the XhoI restriction site in transcription complexes.

pML20-42 or pML20-49 plasmid DNA was linearized with PstI, which cleaves the DNA 30 bp downstream of the XhoI site. Preinitiation complex assembly on this DNA, purification of the preinitiation complexes by gel filtration, generation of the initial elongation complexes, purification of these complexes by Sarkosyl rinsing, and walking of the RNA polymerases to the final desired location were all performed essentially as described previously (40). The transcription complexes were incubated with XhoI (0.27 U/μl) for 4 min at 37°C, followed by chase. (We confirmed that the bulk of the DNA in the reaction was cleaved by XhoI under these conditions.) Following digestion, the reactions were chased for 5 min at 37°C with 50 μM NTPs. RNA was purified, resolved by electrophoresis, and imaged on a PhosphorImager as described above. Protection of the XhoI site was calculated as the ratio of the runoff RNA (at the PstI site) to the sum of the runoff RNA and the RNA which terminated at the XhoI site.

RESULTS

Initially transcribed sequences can strongly modulate the transcriptional competence of RNA polymerase II halted in promoter-proximal locations.

Our laboratory recently reported exonuclease III (exoIII) footprint analyses of RNA polymerase II ternary complexes stalled from 20 to 50 bases downstream of a series of variants of the adenovirus major late promoter (40). These complexes generally remained competent to continue transcription, but many of them, particularly those with 20- to 25-nt transcripts, gave exoIII footprints that were translocated far upstream from their expected positions, reminiscent of arrested complexes (see the pML20-42 footprints in Fig. 1). It had been shown earlier that E. coli RNA polymerase complexes halted at similar locations early in transcription (16, 20, 29) also have upstream-translocated footprints. Thus, it was reasonable to suggest that upstream translocation is a general feature of RNA polymerases halted early in transcript elongation. However, we could not exclude the possibility that our results depended on the particular initially transcribed sequences we chose to study. Those templates contain a segment from +2 to +19 in which all the bases on the nontemplate strand are pyrimidines (Fig. 1). In an initial attempt to address the role of this unusual sequence in the properties of our early transcription complexes, we constructed another template, pML20-49, in which the entire initially transcribed region of pML20-42 was moved to a more downstream location, beginning at +98 (40) (Fig. 1). This allowed us to study promoter-distal transcription complexes which had the same local transcript and template sequence as the promoter-proximal complexes we had previously characterized. We did obtain exoIII footprints characteristic of normal elongation-competent polymerases for some transcription complexes halted on pML20-49. However, with complexes stalled at +120 and +122 on pML20-49, which are analogous to the +23 and +25 complexes on pML20-42, we either observed a weak partial footprint (G122 complex [Fig. 1]) or failed to detect any footprint (A120 complex [Fig. 1]).

As an alternative approach to locating RNA polymerases along the DNA, we tested for the ability of transcription complexes to protect an XhoI restriction enzyme site just downstream of the stalling point. This site was located so that it would be inaccessible in elongation-competent complexes, which protect against exoIII digestion about 18 bp downstream of the point of bond formation (39), but would be accessible in upstream-translocated complexes. The XhoI site in the pML20-42 template begins at +39 (Fig. 1). This site could be cut in 90 to 100% of U20, A23, and G25 complexes but was inaccessible in C27 complexes, in agreement with the extent of downstream protection predicted by our exoIII footprinting results (primary data not shown) (Fig. 1). The same test was then performed with the A120 and G122 complexes on the pML20-49 template. We were somewhat surprised to find that the XhoI site at +136 was completely cut in A120 complexes and 60% cut in G122 complexes (Fig. 1). Thus, even though the A120 and G122 complexes are stalled far downstream of the transcription start site and are fully elongation competent, they show partial or complete upstream translocation.

Based on these data, we realized that the unusual footprints of transcription complexes halted within the first 25 nt of the transcription unit on pML20-42 might result from template or transcript sequence and not from promoter proximity. We therefore decided to test an entirely different initially transcribed sequence. An appropriate sequence was suggested by our earlier exoIII footprinting results on the pML20-23 template (39). Complexes halted at promoter-distal locations on this template were fully elongation competent. These complexes had exoIII footprints centered around the point of bond formation, and the footprints advanced downstream in synchrony with transcription (39) (Fig. 1). Thus, there are no DNA sequences immediately upstream or downstream of the site of initial pausing in the pML20-23 template that provide an intrinsic barrier to normal translocation by RNA polymerase II. We constructed a new template, pML20-23like, by simply relocating the convenient pausing site on pML20-23 so that it was only 23 bases downstream of the transcription start site (Fig. 1). The promoter sequences in pML20-23like from +2 upstream are the identical adenovirus major late promoter-derived elements used in all of our other templates. Note that the initial transcript on pML20-23like is almost entirely purines, in contrast to the polypyrimidine initial transcript for the templates we had previously studied.

To facilitate analysis, we prepared our templates as biotinylated DNA fragments, on which transcription complexes were assembled by incubation in HeLa cell nuclear extract. Transcription was initiated with the dinucleotide ApC and an appropriate subset of the NTPs to halt RNA polymerases at the desired initial location. The initial transcription complexes were purified by washing them with buffer containing 1% Sarkosyl followed by a return to transcription buffer. The complexes were walked to the desired downstream location, with additional buffer washes as necessary, and then challenged with all four NTPs in excess to determine transcriptional competence. All washing and walking steps prior to the final NTP challenge were performed at 30°C. The complexes were then incubated at 37°C for 3 min before addition of the chase NTPs. The use of 30°C for all but the final steps was found to be necessary because of greatly increased arrest at 37°C. The brief 37°C incubation allowed us to compare our results with our earlier footprinting work (40), in which complexes were treated with exoIII at 37°C.

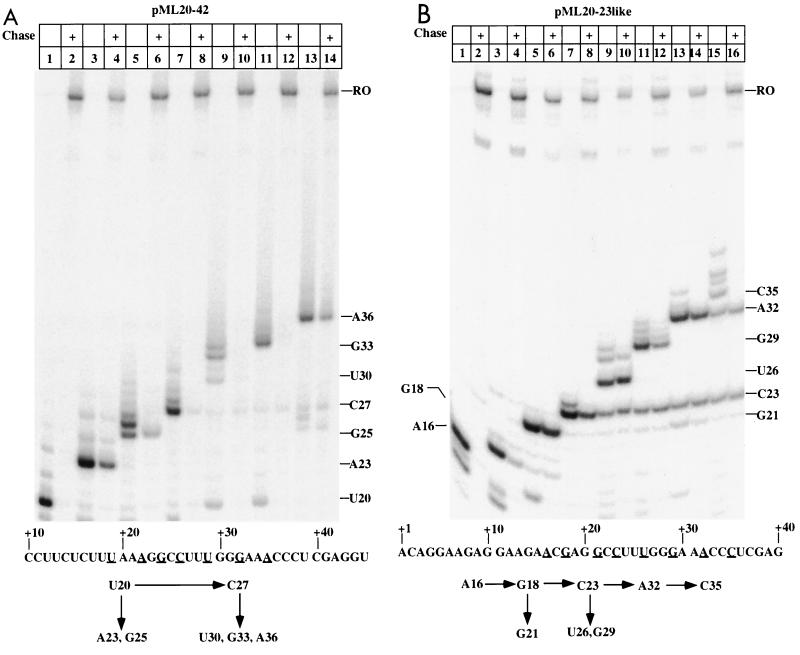

Figure 2A shows the results of such a walking experiment with a set of complexes halted between +20 and +36 on the pML20-42 template. Sarkosyl rinsing took place at +20. Consistent with our earlier findings, the large majority of these complexes could be restarted upon challenge with all four NTPs. The basal arrest level for any pol II transcription complex in this test, including those halted at promoter-distal locations, is about 10% (Table 1 and data not shown). About 40% of the A23 and A36 complexes and about 20% of the G25 complexes did not restart (Table 1). The complexes that failed to resume transcription did not terminate, because they did chase in the presence of elongation factor SII (Fig. 3 and 4). The two complexes which showed the greatest tendency to arrest, A23 and A36, also had strongly upstream-translocated footprints in the earlier exoIII footprinting study (Fig. 1) (40). However, the presence of an upstream-translocated footprint did not always correlate with arrest. In particular, the U20 complex showed no arrest above background, and the G25 complex, which had the most severely upstream-translocated footprint of any complex we studied (40), showed less arrest than the A23 complex.

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional competence of RNA polymerase II complexes halted within two different promoter-proximal regions. Preinitiation complexes were assembled and advanced downstream to either U20 on the pML20-42 template (A) or A16 on the pML20-23like template (B), as described in Materials and Methods. The initial complex for each template was rinsed with Sarkosyl and then advanced as indicated by the schematic at the bottom of each panel. Reactions in the indicated lanes were chased to runoff (RO). Relevant portions of transcript sequence are given at the bottom of each panel; the underlining indicates the locations at which the complexes were halted. In both panels, RNAs were resolved on 13% polyacrylamide-urea gels. The lengths of various RNAs and the position of the runoff transcript are given to the right of each gel. +, chase with 200 μM (each) NTP.

TABLE 1.

Summary of percent of transcription complexes which arrested at various positions on templates

| Template | Fraction remaininga

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 18 | 20 or 21 | 23 | 25 or 26 | 27 | 29 or 30 | 32 | 33 | 35 or 36 | 37 | 39–41 | 42–44 | |

| pML20-42 | 12 (3) | 40 (3) | 22 (3) | 12 (2) | 14 (3) | 37 (2) | 14 (2) | 41 (2) | 9 (2) | 9 | |||

| pML20-46 | 12 (2) | 28 (2) | 13 (2) | 12 (2) | 20 (2) | 32 (2) | 49 (2) | 14 (2) | |||||

| pML20-23like | 6 | 17 | 66 | 45 (3) | 81 (3) | 38 (3) | 59 (2) | 15 (2) | 15 (2) | 14 (2) | |||

The lengths (in nucleotides) of the RNA in the complexes are given across the top. The values, which are averages when multiple determinations were performed, represent the fraction (percent) of a particular complex which remained after a 5-min chase with all four NTPs. The number of independent determinations for those complexes assayed more than once are given by the values in parentheses.

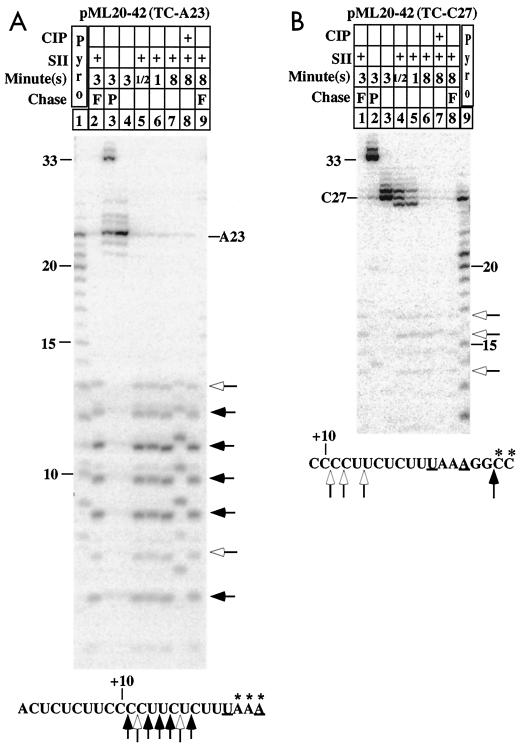

FIG. 3.

Lengths of RNA fragments produced by SII treatment of transcription complexes on the pML20-42 template. A23 (A) or C27 (B) complexes made as described in Materials and Methods were labeled with α-32P-NTPs at the 3′ ends of the transcripts during the last step of walking, as indicated by the asterisks in the transcript sequence below each panel. Treatments with SII and CIP and/or chase with a subset (P) or all (F) of the NTPs were performed in lanes marked with a plus for the times indicated above each panel. The major and minor 3′ products liberated by SII treatment are marked by solid and open arrows, respectively, to the right of each panel. The locations of the cleavages that produced these fragments are given by corresponding arrows on the transcript sequence at the bottom of each panel. RNA length markers were generated by partial pyrophosphorolysis of body-labeled A23 complex (A, lane 1) or C27 complex (B, lane 9). In both panels, the RNAs were resolved on 25% polyacrylamide-urea gels containing 3% bisacrylamide.

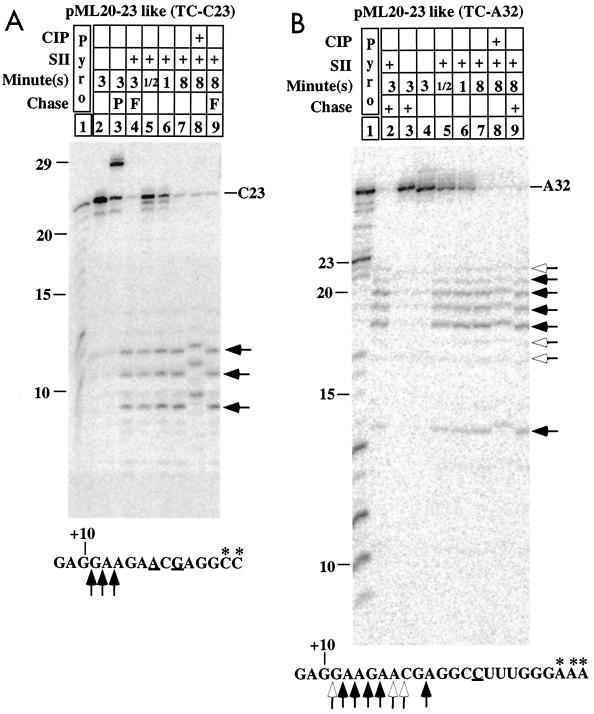

FIG. 4.

Lengths of RNA fragments produced by SII treatment of transcription complexes on the pML20-23like template. C23 (A) or A32 (B) complexes made as described in Materials and Methods were labeled with α-32P-NTPs at the 3′ ends of the transcripts during the last step of walking, as indicated by the asterisks in the transcript sequence below each panel. Treatments with SII and CIP and/or chase with a subset (P) or all (F) of the NTPs were performed in the lanes marked with a plus for the times indicated above each panel. The major and minor 3′ products liberated by SII treatment are marked by solid and open arrows, respectively, to the right of each panel. The locations of the cleavages that produced these fragments are given by corresponding arrows on the transcript sequence at the bottom of each panel. RNA length markers were generated by partial pyrophosphorolysis of body-labeled C23 complex (A, lane 1) or A32 complex (B, lane 1). In both panels, RNAs were resolved on 25% polyacrylamide-urea gels containing 3% bisacrylamide.

We continued this type of experiment on the pML20-46 template, which is similar to pML20-42 but with an additional 10 bp added at the +25 position (40). This change allows efficient generation of transcription complexes halted from +37 to +46. Among these downstream complexes were two which showed significant levels of arrest, C37 and U40 (primary data not shown; Table 1). These two complexes gave significantly upstream-translocated footprints in our earlier study (40).

The results of walking experiments with complexes halted on the pML20-23like template are shown in Fig. 2B. In this case the initial Sarkosyl-rinsed complex was A16. In contrast to the results with the pML20-42 template, all of the complexes halted on pML20-23like between +21 and +32 showed a substantial tendency to arrest. This effect was most pronounced for the G21, U26, and A32 complexes (Table 1). These complexes had not terminated, because they could resume transcription in the presence of SII (Fig. 3 and 4). Complexes which had reached +35 or further downstream on the 20-23like template were fully elongation competent (note in particular lane 15 of Fig. 2B).

It is important to recall that when RNA polymerase II was halted within the same sequence used for the initially transcribed region of pML20-23like, but in a much more downstream location (i.e., at +151 to +160 on the pML20-23 template [39]), no upstream translocation or arrest was observed. Thus, for at least one sequence context, upstream translocation (see below) and failure to continue transcription are particular properties of the early stage of transcript elongation. Also, the comparison of transcription complexes halted at similar locations within the pML20-42 and 20-23like templates shows that the unusual properties of early elongation complexes are strongly modulated by transcript and/or template sequence.

RNA polymerases halted within a range of promoter-proximal locations translocate to a common upstream location, as revealed by SII-mediated transcript cleavage analysis.

RNA polymerase II occupies 30 to 35 bp of template DNA with the catalytic center located about 18 to 20 bp upstream of the leading edge, as judged by exoIII footprinting (6, 39; see also reference 37). Since transcript cleavage in arrested complexes is apparently carried out by the catalytic center (32, 38), the location of RNA polymerase on the template DNA in the arrested complexes can be determined by treating the halted complexes with the transcript cleavage factor SII and measuring the size of the RNA that is liberated from the 3′ end of the transcript. Many promoter-proximal transcription complexes, particularly on the pML20-23like template, have a strong tendency to arrest, so it was not always possible to obtain homogenous preparations of halted complexes. Therefore, for the experiments in this section we advanced polymerases to locations just upstream of the desired final position using nonlabeled NTPs and then performed the final walking step with a single labeled nucleotide. This allowed us to determine the lengths of the RNAs released by SII treatment with no interfering background. We mapped the lengths of the liberated RNAs with reference to RNA markers resolved on the same gel.

We began by testing complexes on the 20-42 template. A23 complexes were prepared in which the three A residues at the 3′ end were labeled (Fig. 3A). As expected from the results shown in Fig. 2, a substantial fraction (about 35% in this experiment) of these complexes could not continue RNA synthesis upon NTP addition (Fig. 3A, lane 3). The nonchaseable complexes were returned to transcriptional competence by the addition of SII (lane 2). The presence of SII either under chase conditions (lane 2) or in the absence of NTPs (lanes 5 to 7) resulted in the production of a set of 7- to 13-nt RNAs, the most prominent of which were 9 to 11 nt long. The mobilities of all of these RNAs were altered by phosphatase treatment (lane 8), confirming that they represent 3′-end fragments produced by transcript cleavage. Note that essentially all of the label originally in the A23 RNA appeared in these cleavage products, even when transcript elongation was possible (compare lanes 2 and 5). This agrees with the earlier observation (40) that A23 complexes have strongly upstream-translocated exoIII footprints. Even though both footprinting and transcript cleavage analysis place the A23 complexes exclusively in an upstream location, these complexes must at least transiently occupy the downstream, transcriptionally competent position, since more than half of them could be chased by readdition of NTPs. This emphasizes the fact that many halted RNA polymerase II transcription complexes exist in equilibrium among several template locations (11, 39, 40).

When fully elongation-competent C27 complexes labeled in the last two C residues (Fig. 3B) were treated with SII, most of the label simply disappeared. This was expected, since SII-mediated cleavage in elongation-competent complexes occurs primarily in dinucleotide units (7, 10), and dinucleotides would not have been recovered in the ethanol precipitation used in the preparation of samples shown in Fig. 3. A small fraction of the SII-mediated cleavages with C27 complexes did give much larger fragments. As with all of the A23 complexes, these larger SII cleavage products appeared to the same extent regardless of the presence of NTPs to allow transcript elongation.

A summary of the results of all of our tests with SII cleavage of pML20-42 and pML20-46 complexes is given in Fig. 5. All complexes except A23 showed some cleavage in short increments. Two aspects of the large-increment (6-nt or greater) cleavages are noteworthy. First, in the three complexes halted at or upstream of position +27, these cleavages took place at a common location near position +12. Secondly, in complexes halted downstream of +27, cleavage did not occur at +12 but at a set of locations no more than 9 nt upstream of the 3′ end.

FIG. 5.

Summary of SII-mediated transcript cleavage on three sets of promoter-proximal RNA polymerase II complexes. TC, transcription complex. The major and minor cleavage sites on each transcript are indicated by the solid and open arrows, respectively. In the case of the C35 transcript, we did not detect any cleavage products directly; we infer from earlier results (10) that the initial cleavage took place at the location shown by the arrow in parentheses.

Although complexes halted on the pML20-23like template were more often arrested than those on the pML20-42 template, many aspects of SII-mediated cleavage in the two complex populations were similar. For example, SII treatment of 3′-end-labeled C23 complexes on pML20-23like resulted in the liberation of 10- to 12-nt RNAs, regardless of the presence or absence of NTPs (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 4 and 7). This is very similar to the results seen with the analogous A23 complexes from the pML20-42 template, even though the sequences in the region in which cleavage took place are completely different. Two other predominantly arrested pML20-23like complexes, U26 (Fig. 5) and A32 (Fig. 4B), also directed SII-mediated cleavage to the same location. This result is particularly striking for the A32 complexes; in this case 18- to 22-nt RNAs were produced upon incubation with SII (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the C35 complex, which is halted only 3 bases further downstream, gave no large cleavage products upon exposure to SII (Fig. 5).

Kinetic analysis reveals strong pausing in the +20 to +30 region during normal transcript elongation.

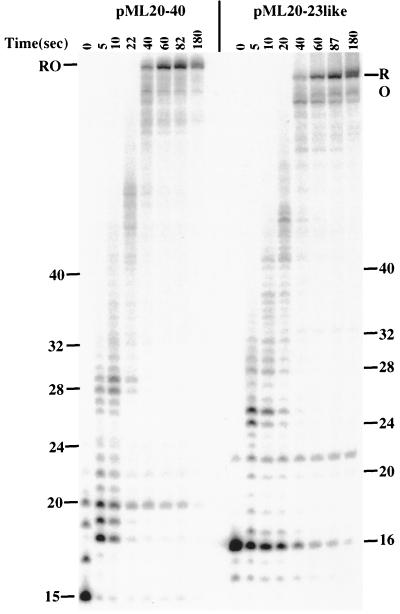

The tendency of some early transcription complexes to undergo upstream translocation when halted between about +20 and +30 on either template suggested that significant pausing might be observed in this region during free-running RNA synthesis. A test of this idea is shown in Fig. 6. Sarkosyl-rinsed complexes were halted at +16 on the pML20-23 template or at +15 on the pML20-40 template. The pML20-40 template is identical to pML20-42 except for a single-base change of C to G at +16 on the nontemplate strand. Polymerases were released into elongation at 30°C by the addition of a 200 μM concentration of all four (unlabeled) NTPs, and samples were taken at the time points indicated in the figure. Under these conditions most polymerases reached the end of the template, at +96, in 40 to 60 s, giving an average transcript elongation rate of about 1.5 to 2 nt/s. On the pML20-40 template, all of the C15 starting complexes had resumed transcription within 5 s. However, a considerable portion of these complexes paused immediately downstream (at +18 through +20) for 5 to 10 s before continuing transcription. Another strong pause was observed just before +30. A fraction of 20-mer transcripts did not resume transcription for a much longer time (Fig. 6, compare the 82- and 180-s time points). However, there was some 20-nt RNA in the starting material, and it is possible that these 20 halted complexes are the source of the slow-restarting 20-nt complexes. The initial 16-mer complexes on the pML20-23 template restarted much more slowly than the initial complexes on pML20-40. In addition to transient pauses at +24 and +25 and at +28 to +31, some of the pML20-23like complexes apparently arrested at +21, since a significant level of 21-mers could not continue transcription even after 3 min of incubation with NTPs.

FIG. 6.

Kinetics of transcript elongation by RNA polymerase II complexes on pML20-40 and pML20-23like templates. RNA polymerase II complexes advanced to +15 or +16 on the pML20-40 and pML20-23like templates were Sarkosyl rinsed and allowed to resume transcription in the presence of 200 μM (each) all four NTPs at 30°C. The reactions were stopped by addition of phenol-chloroform at the indicated time points. The RNAs were resolved on a 13% polyacrylamide-urea gel. The numbers on both sides of the gel indicate the sizes of the transcripts in nucleotides. RO, runoff.

DISCUSSION

Footprinting studies with RNA polymerase II complexes halted from 20 to 50 nt downstream of the transcription start site gave two unexpected results: first, complexes halted early in elongation (before +26 for the template used) were strongly upstream translocated but not predominantly arrested, and second, some upstream translocation was observed with complexes as far as 40 nt downstream of the transcription start site (40). These findings, combined with earlier work on E. coli RNA polymerase (29), suggested that RNA polymerases may be generally prone to upstream translocation during the early stages of transcript elongation. In this paper we show that the sequence context used for our earlier footprinting experiments can lead to anomalous behavior by RNA polymerase II even in a downstream location. However, we observed both upstream translocation and arrest with a second initially transcribed region, even though this sequence in a promoter-distal location was traversed normally by RNA polymerase II. Thus, in at least one sequence context, halting RNA polymerase II early in elongation is, by itself, sufficient to provoke both upstream translocation and arrest. Sequence strongly modulates the consequences of promoter-proximal stalling, since most transcription complexes halted at +20 to +33 on the (polypyrimidine) pML20-42 template were upstream translocated (40) but nevertheless elongation competent. In spite of the different fates of transcription complexes halted in the two sequence contexts, we found an underlying similarity: upstream translocation prior to +32 on both templates always relocated RNA polymerase such that about 12 to 13 nt of RNA remained upstream of the catalytic center.

A well-documented model for the transcription complex proposes that continued competence for elongation (and resistance to upstream translocation and arrest) depends primarily on the RNA-DNA hybrid and the sliding clamp of the polymerase, which interacts with DNA downstream of the point of bond formation (reviewed in reference 27). While this model explains the behavior of RNA polymerase at promoter-distal arrest sites, it does not predict the results we report here with transcription complexes in the early stages of RNA chain elongation. Neither the DNA downstream of the point at which the complexes were halted nor the RNA-DNA hybrids within the complexes should have posed a significant barrier to the resumption of transcription by RNA polymerase II. The DNA downstream of the region at which polymerases were stalled in our experiments is the same plasmid DNA sequence that permitted full resumption of transcription (without upstream translocation) for RNA polymerases halted at promoter-distal locations (Fig. 1) (40). Furthermore, a weak RNA-DNA hybrid is not a common feature of the arrested promoter-proximal complexes. For example, the U26 complex on pML20-23like, whose transcript ends in three U residues, is strongly arrested. However, the analogous complex on the pML20-42 template, U29, was not arrested at all. Note that these two complexes should share identical RNA-DNA hybrids and identical DNA sequences downstream of the point at which RNA synthesis was halted (Fig. 1). The U26 and U29 complexes only differ in sequence beginning 9 bases upstream of the point of bond formation.

We conclude from our data that promoter-proximal and promoter-distal RNA transcription complexes with identical local transcript and template sequences can have very different properties. It is important to stress the limitations to this conclusion. First, we cannot say from the findings presented in this paper that the functional difference between promoter-proximal and promoter-distal complexes is simply transcript length. The promoter-proximal complexes could differ in some fundamental way from their promoter-distal counterparts. However, other workers in this laboratory have very recently shown that promoter-distal RNA polymerase II complexes whose transcripts are trimmed to 20 to 50 nt display the same elongation competence as early elongation complexes with the same transcript sequence and transcript length (Újvári and Luse, submitted). Also, since we have analyzed only two initially transcribed regions, we cannot conclude that in all sequence contexts RNA polymerases halted early in elongation will tend to translocate upstream. It is interesting that stalled early elongation complexes on either template tend to translocate upstream to a common location. This suggests (but does not prove) a common, sequence-independent aspect to early elongation on both templates.

Our results do indicate that the existing model of the transcription complex must be extended in order to explain the properties of promoter-proximal complexes. We propose that in addition to the RNA-DNA hybrid and the sliding clamp, the transcript itself, well upstream of the hybrid, contributes to the elongation competence of the transcription complex. An attractive mechanism for this effect would involve the interaction of the nascent RNA with the RNA polymerase beginning relatively far from the 3′ end, roughly 25 to 30 nt upstream. In the multisubunit RNA polymerases, immediately after bond formation the transcript forms an RNA-DNA hybrid of 8 to 9 nt followed by passage through an exit channel (19). RNase protection studies indicate that 14 to 17 nt of RNA upstream of the 3′ end (18) are tightly associated with the polymerase and inaccessible to nuclease (7, 17, 25; see also reference 34). In the present work, we show that the completion of the RNA-DNA hybrid and the filling of the exit channel after the synthesis of about 13 nt results in an unusually stable intermediate for the RNA polymerase II nascent elongation complex, as indicated by the fact that transcription complexes arrested between this point and +25 to +32 (depending on the template) all translocate upstream to a common location with only about 13 nt of RNA remaining upstream of the 3′ end. We suppose that once the nascent RNA has reached a critical length and can interact with the putative upstream interaction site, the transcription complex begins to be stabilized in its final elongation configuration, thereby preventing reverse threading of the transcript and inhibiting upstream translocation. This event has presumably occurred by +27 on the pML20-42 template and by +35 on the pML20-23like template. If the nascent transcript continues to interact with the RNA polymerase for more than 40 nt upstream of the 3′ end, the transition into the final, upstream translocation-resistant form of the elongation complex might not be complete until this upstream binding site is filled. This could explain the partially arrested nature of complexes with 36, 37, or 40 nt of RNA (Fig. 5 and Table 1); these complexes showed upstream translocation in footprinting studies (40). We do not know why complexes with RNAs shorter than the critical length of 25 to 32 nt are particularly prone to upstream translocation. There may be a transient unfavorable interaction of the nascent RNA as it emerges from the initial exit channel, prior to the point at which the transcript is sufficiently long to reach the second interaction site.

A model invoking interaction of an upstream segment of the transcript with the RNA polymerase not only explains our results but also agrees with a number of other observations. Milan and colleagues (26) showed that E. coli transcription complexes protect the nascent RNA against moderate levels of RNase attack over two regions: the first 14 to 16 nt and 30 to 45 nt from the 3′ end. The more upstream of these sites could correspond to the transcript-RNA polymerase interaction site proposed above. The potential existence of long RNA binding domains within RNA polymerase was suggested by earlier studies from the Chamberlin laboratory on binary complexes of RNA and RNA polymerase (1, 13). In these experiments, maximal binding of RNA oligonucleotides to either E. coli RNA polymerase or yeast RNA polymerase II was not achieved with RNAs less than about 30 nt long. Our model is also consistent with the recent findings of Kireeva et al. (15). In these studies, yeast RNA polymerase II transcription complexes were assembled from purified yeast polymerase and a minimal nucleic acid scaffold, including an initial 9-nt RNA primer. These non-promoter-initiated complexes strongly resemble promoter-initiated complexes in a number of assays. Significantly, halted yeast RNA polymerase II complexes bearing 9- or 40-nt transcripts were much more likely to resume transcription than complexes containing 20-, 23-, or 34-nt RNAs. Finally, the concept of an upstream RNA binding domain is also consistent with recent data from other workers in this laboratory, who have shown that hybridization of oligonucleotides to the region 30 to 45 nt upstream of the 3′ end can cause significant arrest in otherwise elongation-competent promoter-distal RNA polymerase II transcription complexes (Újvári and Luse, submitted). Note that in these experiments, hybridization to more 3′-proximal positions along the transcript, such as 17 to 27 bases upstream of the site of bond formation, actually reduced the basal level of arrest in the transcription complexes. This presumably reflects blocking of reverse threading of the transcript and thus of upstream translocation, as shown by Reeder and Hawley (34).

The results reported here indicate that the transition from initiation to elongation by RNA polymerase II is significantly more extended than previously appreciated. Most earlier work on this transition has focused on the events which occur between roughly the formation of the 10th and 15th bonds. These include the end of abortive initiation, after about 10 bonds have been made (8), and the reclosure of the upstream end of the initial transcription bubble, which also begins to occur at about +10 (5, 8). Kugel and Goodrich (21) localized the rate-limiting step in nonactivated transcription, using kinetic studies, to a point between the initiation site and +15. RNA polymerase II transcript initiation complexes that lack TFIIH (22) or which have been exposed to inhibitors of the ERCC3 helicase of TFIIH (4) cease transcription about 10 to 15 bases downstream of the transcription start site.

The transition(s) just described is often termed promoter clearance. We note that RNA polymerase II complexes halted as far downstream as +32 translocate upstream, leaving the body of the polymerase covering the transcript initiation site (reference 40 and the present work). It thus seems likely (although this idea has not been tested by us) that RNA polymerase II complexes halted 10 to 15 bases after initiation would not allow the entry of another RNA polymerase. This suggests that another frequently used term for the +10 to +15 transition(s), namely, promoter escape, might be a more appropriate description for this step than promoter clearance. We emphasize that the event(s) involved in promoter escape has been completed before the transitions we study here, since the most promoter-proximal complex we tested was stalled at +16. Moreover, all of the complexes we studied were rinsed with 1% Sarkosyl before further assay, which should have removed the general initiation factors. We did not test for the presence of these factors directly, but our earlier footprinting studies with, for example, U20 complexes on the pML20-42 template (40), revealed no template protection over the TATA box, which should have been occupied had TFIID been present (33, 41) and no protection downstream to about +46, which would have been occupied had TFIIH been present (14). Also, we confirmed that the presence of dATP had no effect on the ability of one of our highly arrested complexes to resume transcription (data not shown).

After the escape step, RNA polymerase must undergo a second transition, which we observed between +25 and +27 (on the 20-42 template) or +32 and +35 (on the 20-23like template). Following this transition, the polymerase begins to display the properties of the final elongation-committed form. In particular, transcription complexes which have passed this transition no longer translocate far upstream to cover the initiation site. We therefore favor the term promoter clearance for this second major transition within the nascent RNA polymerase II transcription complex. Note that pauses at or just before this point are observed in free-running transcription reactions (Fig. 6) It is also important to note that the postescape transitions that we observed are not, as best we can determine, dependent upon the Sarkosyl rinsing step. Preliminary tests indicate that we observe similar properties for halted complexes which have not been rinsed. For example, C23 complexes on the pML20-23like template which have not been exposed to Sarkosyl are predominantly arrested. They are also at least partially upstream translocated, since about 50% of the XhoI sites (Fig. 1) could be cleaved in these complexes (data not shown).

After the clearance transition, the RNA polymerase is apparently still not in the final elongating state. For example, several complexes on the pML20-42 and 20-46 templates which are well downstream of +27, namely, A36, C37, and U40, showed significant arrest (Fig. 5 and Table 1) and upstream translocation of the exoIII footprint (40).

A major motivation to undertake the study of promoter-proximal transcription complexes is the observation that many RNA polymerase II transcription units contain a polymerase halted, by mechanisms largely unknown, between about 25 and 50 nt downstream of the transcription start site (24). As noted above, most of the well-studied transitions for newly initiated RNA polymerase II are complete by the point at which 15 bonds have been made. We report here that RNA polymerase II undergoes at least one more transition before reaching the final form of the transcript elongation complex downstream of +40. We suggest that the tendency of the polymerase to fall into arrest with transcripts in the 25- to 40-nt size range when transcribing pure DNA templates identifies a potential substrate for antielongation and clearance mechanisms in the cell.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grant GM 29487 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altmann C R, Solow-Cordero D E, Chamberlin M J. RNA cleavage and chain elongation by Escherichia coli DNA-dependent RNA polymerase in a binary enzyme·RNA complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3784–3788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artsimovitch I, Landick R. Pausing by bacterial RNA polymerase is mediated by mechanistically distinct classes of signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7090–7095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borukhov S, Sagitov V, Goldfarb A. Transcript cleavage factors from E.coli. Cell. 1993;72:459–466. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dvir A, Conaway R C, Conaway J W. Promoter escape by RNA polymerase II—a role for an ATP cofactor in suppression of arrest by polymerase at promoter-proximal sites. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23352–23356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiedler U, Timmers H T. Peeling by binding or twisting by cranking: models for promoter opening and transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. Bioessays. 2000;22:316–326. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200004)22:4<316::AID-BIES2>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gu W, Powell W, Mote J, Jr, Reines D. Nascent RNA cleavage by arrested RNA polymerase II does not require upstream translocation of the elongation complex on DNA. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25604–25616. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu W G, Reines D. Variation in the size of nascent RNA cleavage products as a function of transcript length and elongation competence. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30441–30447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holstege F C P, Fiedler U, Timmers H T M. Three transitions in the RNA polymerase II transcription complex during initiation. EMBO J. 1997;16:7468–7480. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izban M G, Luse D S. The RNA polymerase-II ternary complex cleaves the nascent transcript in a 3′->5′ direction in the presence of elongation factor-SII. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1342–1356. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izban M G, Luse D S. SII-facilitated transcript cleavage in RNA polymerase-II complexes stalled early after initiation occurs in primarily dinucleotide increments. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12864–12873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izban M G, Luse D S. The increment of SII-facilitated transcript cleavage varies dramatically between elongation competent and incompetent RNA polymerase-II ternary complexes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12874–12885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izban M G, Samkurashvili I, Luse D S. RNA polymerase II ternary complexes may become arrested after transcribing to within 10 bases of the end of linear templates. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2290–2297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson T L, Chamberlin M J. Complexes of yeast RNA polymerase II and RNA are substrates for TFIIS-induced RNA cleavage. Cell. 1994;77:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim T K, Ebright R H, Reinberg D. Mechanism of ATP-dependent promoter melting by transcription factor IIH. Science. 2000;288:1418–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kireeva M L, Komissarova N, Waugh D S, Kashlev M. The 8-nucleotide-long RNA:DNA hybrid is a primary stability determinant of the RNA polymerase II elongation complex. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6530–6536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komissarova N, Kashlev M. RNA polymerase switches between inactivated and activated states by translocating back and forth along the DNA and the RNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15329–15338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komissarova N, Kashlev M. Transcriptional arrest: Escherichia coli RNA polymerase translocates backward, leaving the 3′ end of the RNA intact and extruded. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1755–1760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komissarova N, Kashlev M. Functional topography of nascent RNA in elongation intermediates of RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14699–14704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korzheva N, Mustaev A, Kozlov M, Malhotra A, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A, Darst S A. A structural model of transcription elongation. Science. 2000;289:619–625. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krummel B, Chamberlin M J. Structural analysis of ternary complexes of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase-deoxyribonuclease-I footprinting of defined complexes. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:239–250. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90918-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kugel J F, Goodrich J A. A kinetic model for the early steps of RNA synthesis by human RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40483–40491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006401200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar K P, Akoulitchev S, Reinberg D. Promoter-proximal stalling results from the inability to recruit transcription factor IIH to the transcription complex and is a regulated event. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9767–9772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landick R. Transcription—shifting RNA polymerase into overdrive. Science. 1999;284:598–599. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lis J. Promoter-associated pausing in promoter architecture and postinitiation transcriptional regulation. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:347–356. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marr M T, Roberts J W. Function of transcription cleavage factors GreA and GreB at a regulatory pause site. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milan S, D'Ari L, Chamberlin M J. Structural analysis of ternary complexes of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: ribonuclease footprinting of the nascent RNA in complexes. Biochemistry. 1999;38:218–225. doi: 10.1021/bi9818422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nudler E. Transcription elongation: structural basis and mechanisms. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:1–12. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nudler E, Avetissova E, Markovtsov V, Goldfarb A. Transcription processivity: protein-DNA interactions holding together the elongation complex. Science. 1996;273:211–217. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nudler E, Goldfarb A, Kashlev M. Discontinuous mechanism of transcription elongation. Science. 1994;265:793–796. doi: 10.1126/science.8047884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nudler E, Gusarov I, Avetissova E, Kozlov M, Goldfarb A. Spatial organization of transcription elongation complex in Escherichia coli. Science. 1998;281:424–428. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nudler E, Mustaev A, Lukhtanov E, Goldfarb A. The RNA-DNA hybrid maintains the register of transcription by preventing backtracking of RNA polymerase. Cell. 1997;89:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orlova M, Newlands J, Das A, Goldfarb A, Borukhov S. Intrinsic transcript cleavage activity of RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4596–4600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purnell B A, Emanuel P A, Gilmour D S. TFIID sequence recognition of the initiator and sequences farther downstream in Drosophila class II genes. Genes Dev. 1994;8:830–842. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeder T C, Hawley D K. Promoter proximal sequences modulate RNA polymerase II elongation by a novel mechanism. Cell. 1996;87:767–777. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reines D, Conaway R C, Conaway J W. Mechanism and regulation of transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:342–346. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reines D, Ghanouni P, Li Q Q, Mote J. The RNA polymerase-II elongation complex-factor-dependent transcription elongation involves nascent RNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15516–15522. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice G A, Chamberlin M J, Kane C M. Contacts between mammalian RNA polymerase-II and the template DNA in a ternary elongation complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:113–118. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudd M D, Izban M G, Luse D S. The active site of RNA polymerase II participates in transcript cleavage within arrested ternary complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8057–8061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samkurashvili I, Luse D S. Translocation and transcriptional arrest during transcript elongation by RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23495–23505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samkurashvili I, Luse D S. Structural changes in the RNA polymerase II transcription complex during transition from initiation to elongation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5343–5354. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawadogo M, Roeder R G. Interaction of a gene-specific transcription factor with the adenovirus major late promoter upstream of the TATA box region. Cell. 1985;43:165–175. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sidorenkov I, Komissarova N, Kashlev M. Crucial role of the RNA:DNA hybrid in the processivity of transcription. Mol Cell. 1998;2:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toulmé F, Mosrin-Hauman C, Sparkowski J, Das A, Leng M, Rahmouni A R. GreA and GreB proteins revive backtracked RNA polymerase in vivo by promoting transcript trimming. EMBO J. 2000;19:6853–6859. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uptain S M, Kane C M, Chamberlin M J. Basic mechanisms of transcript elongation and its regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:117–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoo O, Yoon H, Baek K, Jeon C, Miyamoto K, Ueno A, Agarwal K. Cloning, expression and characterization of the human transcription elongation factor, TFIIS. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1073–1079. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]