Abstract

Background

Unintended pregnancy among adolescents represents an important public health challenge in high‐income countries, as well as middle‐ and low‐income countries. Numerous prevention strategies such as health education, skills‐building and improving accessibility to contraceptives have been employed by countries across the world, in an effort to address this problem. However, there is uncertainty regarding the effects of these interventions, hence the need to review the evidence‐base.

Objectives

To assess the effects of primary prevention interventions (school‐based, community/home‐based, clinic‐based, and faith‐based) on unintended pregnancies among adolescents.

Search methods

We searched all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status up to November 2015. We searched the Cochrane Fertility Regulation Group Specialised trial register, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2015 Issue 11), MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, Social Science Citation Index and Science Citation Index, Dissertations Abstracts Online, The Gray Literature Network, HealthStar, PsycINFO, CINAHL and POPLINE and the reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

We included both individual and cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating any interventions that aimed to increase knowledge and attitudes relating to risk of unintended pregnancies, promote delay in the initiation of sexual intercourse and encourage consistent use of birth control methods to reduce unintended pregnancies in adolescents aged 10 years to 19 years.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trial eligibility and risk of bias, and extracted data. Where appropriate, binary outcomes were pooled using a random‐effects model with a 95% confidence interval (Cl). Where appropriate, we combined data in meta‐analyses and assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 53 RCTs that enrolled 105,368 adolescents. Participants were ethnically diverse. Eighteen studies randomised individuals, 32 randomised clusters (schools (20), classrooms (6), and communities/neighbourhoods (6). Three studies were mixed (individually and cluster randomised). The length of follow up varied from three months to seven years with more than 12 months being the most common duration. Four trials were conducted in low‐ and middle‐ income countries, and all others were conducted in high‐income countries.

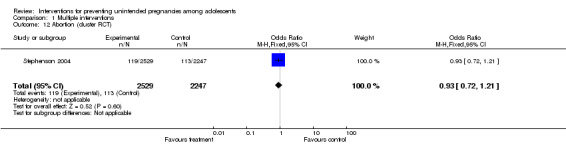

Multiple interventions

Results showed that multiple interventions (combination of educational and contraceptive‐promoting interventions) lowered the risk of unintended pregnancy among adolescents significantly (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.87; 4 individual RCTs, 1905 participants, moderate quality evidence. However, this reduction was not statistically significant from cluster RCTs. Evidence on the possible effects of interventions on secondary outcomes (initiation of sexual intercourse, use of birth control methods, abortion, childbirth, sexually transmitted diseases) was not conclusive.

Methodological strengths included a relatively large sample size and statistical control for baseline differences, while limitations included lack of biological outcomes, possible self‐report bias, analysis neglecting clustered randomisation and the use of different statistical tests in reporting outcomes.

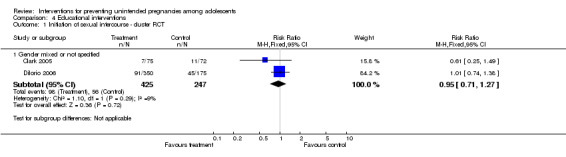

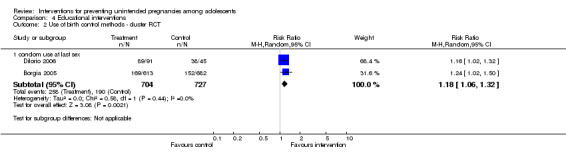

Educational interventions

Educational interventions were unlikely to significantly delay the initiation of sexual intercourse among adolescents compared to controls (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.27; 2 studies, 672 participants, low quality evidence).

Educational interventions significantly increased reported condom use at last sex in adolescents compared to controls who did not receive the intervention (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.32; 2 studies, 1431 participants, moderate quality evidence).

However, it is not clear if the educational interventions had any effect on unintended pregnancy as this was not reported by any of the included studies.

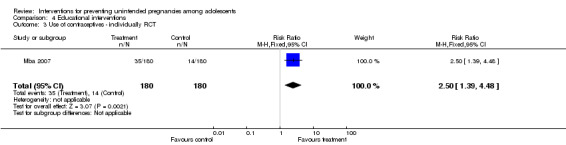

Contraceptive‐promoting interventions

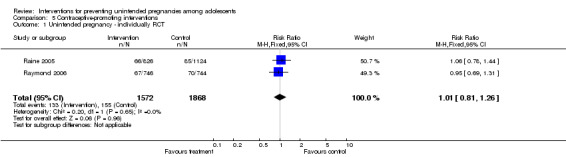

For adolescents who received contraceptive‐promoting interventions, there was little or no difference in the risk of unintended first pregnancy compared to controls (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.26; 2 studies, 3,440 participants, moderate quality evidence).

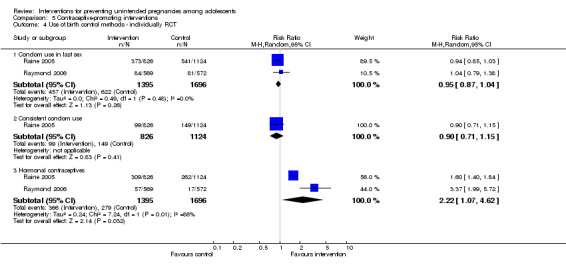

The use of hormonal contraceptives was significantly higher in adolescents in the intervention group compared to those in the control group (RR 2.22, 95% CI 1.07 to 4.62; 2 studies, 3,091 participants, high quality evidence)

Authors' conclusions

A combination of educational and contraceptive‐promoting interventions appears to reduce unintended pregnancy among adolescents. Evidence for programme effects on biological measures is limited. The variability in study populations, interventions and outcomes of included trials, and the paucity of studies directly comparing different interventions preclude a definitive conclusion regarding which type of intervention is most effective

Plain language summary

Interventions for preventing unintended pregnancy among adolescents

Interventions for preventing unintended pregnancy include any activity (health education or counselling only, health education plus skills‐building, health education plus contraception education, contraception education and distribution, faith‐based group or individual counselling) designed to increase adolescents' knowledge and attitudes relating to risk of unintended pregnancies; promote delay in initiation of sexual intercourse; encourage consistent use of birth control methods and reduce unintended pregnancies.

This review included 53 randomised controlled trials comparing these interventions to various control groups (mostly usual standard sex education offered by schools). The search for trials was not limited by country, though most of the included trials were conducted in high‐income countries, with just four trials in middle‐ and low‐income countries, mainly representing the lower socio‐economic groups. Interventions were administered in schools, community centres, healthcare facilities and homes. Meta‐analysis was performed for studies where it was possible to extract data.

Only interventions involving a combination of education and contraception promotion (multiple interventions) was seen to significantly reduce unintended pregnancy over the medium‐term and long‐term follow‐up period. Results for behavioural (secondary) outcomes were inconsistent across trials.

Limitations of this review include reliance on programme participants to report their behaviours accurately and methodological weaknesses in the trials.

Summary of findings

Background

The World Health Organization defines adolescents as individuals between 10 years and 19 years of age (WHO 1980). Adolescence is a period of transition, growth, exploration and opportunities. During this phase of life, adolescents experience physical and sexual maturation and tend to develop an increased interest in sex, with attendant risks of unintended pregnancies, health risks associated with early childbearing, abortion outcomes, and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS.

Adolescents who have an unintended pregnancy face a number of challenges, including abandonment by their partners, inability to complete school education (which ultimately limits their future social and economic opportunities), and increased adverse pregnancy outcomes (Henshaw 2000; Koniak‐Griffin 2001; Kosunen 2002; Moore 1993; Phipps 2002;, Upchurch 1990).

Description of the condition

Unintended pregnancy among adolescents is a common public health problem in industrialised, middle‐ or low‐income countries (WHO 1995). The number of unintended pregnancies is reported to be on the decline in the US, with the Office of Adolescent Health reporting a 10% drop from 2012 to 2013, and more than a 50% drop between 1991 and 2013 (Hamilton 2014). The same decline was seen across all racial groups but some disparities remain: Black and Hispanic teens make up a large proportion of teen births in the US (Hamilton 2014). The same trend is reported in most countries (World Bank 2014): in sub‐Saharan Africa, there was a decline in the fertility rate among adolescents from 134 live births per 1000 in 2000 to 115 live births per 1000 in 2010, although these rates are still high when compared to the world standard; in India, adolescent pregnancies constitute 19% of total fertility (Mehra 2004) but this rate has been declining with 77 live births per 1000 in 2010 as compared to 109 live births per 1000 in 2000; and an Israeli study estimated the incidence of teenage pregnancy in Israel to be 32 live births per 1000 adolescent girls (Sikron 2003).

Repeat pregnancies among adolescents are also common and are associated with increased risks of adverse maternal and child health outcomes (Nelson 1990). Unintended pregnancy is not only costly to the teenagers and their families, it is also a huge financial burden to the state, borne by taxpayers in high‐income nations. It was estimated that spending on medicaid‐subsidised medical care related to unintended pregnancy totals more than USD 12 billion annually (Thomas 2009). These costs include welfare support for mothers experiencing financial difficulties, implementation of programmes (educational and skills training) to empower mothers to gain financial independence, and lost tax revenues arising from reduced employability and earnings (Burt 1986; Haveman 1997; Maynard 1996; Rich‐Edwards 2002 ).

Adolescent mothers are more likely to perform poorly in school, come from low socio‐economic homes and a less advantageous environment; and be themselves children of mothers with limited school education and a history of unintended teenage pregnancies (Elfebein 2003). Children born to adolescent mothers are more likely to have low birth weight, and become victims of physical neglect and abuse (Elfebein 2003), more likely to end up as school‐dropouts like their mothers, or engage in delinquent behaviours (Monea 2011).

Description of the intervention

On account of the short‐ and long‐term consequences of unintended pregnancies for the adolescent, their families and society at large (Burt 1990; Trussell 1997), government public health programmes, bilateral agencies and non‐governmental organisations (NGOs) have implemented (and continue to implement) various interventions to address the problem, using a variety of approaches.

Such interventions include:

curriculum‐based sex and STD/HIV education programmes (Safer Choices (Coyle 2001), Becoming a Responsible Teen (St. Lawrence 2005), All for You (Coyle 2006));

abstinence‐alone programmes (Postponing Sexual Involvement (Kirby 1997b), Sex can Wait (Denny 2006));

comprehensive programmes ‐ a combination of multiple components (Sexual Health and Relationships (SHARE) (Henderson 2007), RIPPLE (Stephenson 2004), Children's Aid Society‐Carrera program (Philliber 2002));

sex and STD/HIV education programmes for parents and teens (Keepin' it R.E.A.L (Dilorio 2006), REAL Men (Dilorio 2007));

interactive video‐based and computer‐based interventions (DeLamater 2000, Downs 2004);

clinical protocol and one‐on‐one programmes, which include advance promotion and provision of emergency contraceptives (Raine 2000; Raymond 2006);

clinic‐based programmes (Lindberg 2006), promotion of clinic appointments and supportive activities (Danielson 1990, Orr 1996);

youth development programmes (service learning such as the Reach for health service learning program (O'Donnell 2003), Teen Outreach Program (TOP) (Philliber 1992); and

vocational education (Summer Training and Education Program (STEP) (Grossman 1992).

How the intervention might work

Interventions that are designed to reduce teen pregnancy appear to be most effective when a multifaceted approach is used, as the problem is multiple determined and multidimensional. The interventions should not only focus on sexual factors and related consequences, they should also include non‐sexual factors such as skills training, and personal development. Further, stakeholders including pregnant teens, parents, the health sector, schools and churches should work together to devise programmes that are practical, evidence based, culturally appropriate and acceptable to the target population.

Some interventions focus primarily on changing the psychosocial risk and protective factors that involve sexuality. One such is Safer Choices (Coyle 2001) which improves teens’ knowledge about the risks and consequences of pregnancy and STDs, values and attitudes regarding sex, perceptions of peer norms about sex and contraception, self‐efficacy (ability to say ‘no’ to unwanted sex), consistent use of contraception including condoms, and their intentions regarding sexual behaviours. Some interventions promote abstinence only (Denny 2006), and others add a comprehensive, health‐education approach wherein safer sexual practices are also included (Jemmott 1998). Sex and STD/HIV education programmes for parents and teens seek to improve parent/child communication regarding sexual health and sexuality, and promote connectedness (Dilorio 2006). Clinic protocols and one‐on‐one programmes promote practices that provide advance supplies of emergency contraceptives to high risk adolescents (Lindberg 2006; Orr 1996), as well as providing health counselling for young men (Danielson 1990).

Other interventions, such as youth development endeavours, focus on non‐sexual factors, which aim to engender positive values in adolescents, inspire hope for the future, improve performance in school and bolster family relationships. They also aim to reduce risky behaviours such substance abuse and violence; promote service‐learning programmes which provide supervised voluntary community‐service opportunities, as well as mentoring opportunities on skills‐building (O'Donnell 2003, Philliber 1992). Some make use of trained peer educators to conduct the health‐education sessions serving as mentors or role models in achieving sustained behavioural changes (Borgia 2005).

Experts suggest that in order to reduce teenage pregnancies, interventions should be designed to address multiple sexual and non‐sexual antecedents that correlate with adolescent sexuality, and which may be related to the adolescents, their families, schools, communities and cultural factors ‐ notably religion (Kirby 2002a). Interventions should also include publicly‐financed mass media campaigns and expanding government‐subsidised family‐planning services (Thomas 2012).

With regard to cultural factors, while one Israeli study showed that the incidence of pregnancy was three times higher among Muslims than among Jews (Sikron 2003), another showed that women with no religious affiliation had the highest unintended pregnancy rate compared to women with religious affiliation, and that these women were also most likely to end the pregnancy by abortion (Finer 2006). This raises questions about the possible impact of faith‐based interventions, which tend to start early and are often sustained for long periods at the home and community levels. In some communities, premarital or extra‐marital sex, whether in young or older people, is seen by the larger society as a violation of morality. Most moral codes and laws that prescribe acceptable conducts of sexual relationships have their origin in major religions.

Why it is important to do this review

Evaluation studies of specific interventions as well as reviews and meta‐analyses of the effects of current strategies show discrepant evidence of effectiveness (DiCenso 2002, Fullerton 1997, Maness 2013). For example, a review of 73 studies reported that four intervention programmes resulted in delay in initiation of sexual intercourse, increased condom and contraceptive use, and reduced unintended teenage pregnancy (Kirby 2002b). The interventions identified as being effective in that review were sex and HIV education curricula; one‐on‐one clinician‐patient protocols in healthcare settings; service learning programmes; and intensive youth development programmes (Kirby 2002b).

Another systematic review of randomised controlled trials showed that several primary prevention measures did not delay the initiation of sexual intercourse nor reduce the number of pregnancies among adolescents (DiCenso 2002, Maness 2013). As this review demonstrated, a small number of programmes actually led to an increase in the number of pregnancies among partners of male participants of abstinence programmes (DiCenso 2002). One author had attributed the small decline in the level of adolescent pregnancy in the US to a decrease in sexual activity and an increase in contraceptive use, especially long‐term contraceptive injectables and implants (Pettinato 2003), fear of contracting HIV/AIDS, health education programmes, a changing moral climate, new contraceptives, and improved economic climate (Klerman 2002).

It is possible that discrepancies in results of existing reviews and meta‐analyses may partly be explained by design flaws in the evaluation of studies and reviews. For example, most reviews included non‐randomised and observational studies; most were limited in scope through their exclusion of unpublished studies; very few included rigorous statistical analysis, and some were based on surveys (Franklin 1997).

This calls for rigorous reviews to more clearly elucidate the effects of these interventions, taking cognizance of the complex and multi‐factorial nature of adolescent sexuality and pregnancy.

Moreover, most of the reviews were limited to industrialised nations (DiCenso 2002), and thus could not account for any influences of social, cultural, and economic factors in diverse populations. Such reviews have limited value to bilateral agencies and international NGOs working in the field of adolescent health promotion. In light of this, the Cochrane systematic approach was used to limit bias (systematic errors) and reduce chance effects, thereby providing more reliable results upon which to draw conclusions and make rational and evidence‐based recommendations (Antman 1992; Oxman 1993). This review draws from the expertise and resources already developed within Cochrane in general and Cochrane Fertility Regulation in particular.

In this review, we assessed and summarised the effects that adolescent pregnancy prevention interventions have on: [i] adolescents' knowledge and attitudes relating to risks of unintended pregnancies, [ii] delay in initiation of sexual intercourse, [iii] consistent use of birth control methods, and [iv] reduction in unintended pregnancies. To reduce publication bias (Cook 1993, Dickersin 1990), we considered all published and unpublished randomised controlled studies that assessed the effectiveness of interventions to reduce unintended pregnancy among adolescents, written in any language. Studies conducted in both high‐income and middle‐ and low‐income countries were also considered (WHO 1995). This body of evidence will help to elucidate what works, and what does not in the efforts to reduce unintended pregnancies among adolescents, and thus help to justify the use of scarce resources, train public health professionals, and facilitate the design of interventions that are effective.

Objectives

To assess the effects of primary prevention interventions (school‐based, community/home‐based, clinic‐based, and faith‐based) on unintended pregnancies among adolescents.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials, including cluster randomised trials where the unit of randomisation is the household, community, youth centre, school, classroom, health facility, or faith‐based institution.

Types of participants

Male and female adolescents aged 10 years to 19 years

Types of interventions

Any activity (either health education or counselling only, health education plus skills‐building, health education plus contraception‐education, contraception education and distribution, faith‐based group or individual counselling) designed to increase adolescents' knowledge and attitudes about the risk of unintended pregnancies, promote delay in initiation of sexual intercourse, encourage consistent use of birth control methods, and reduce unintended pregnancies. Where our search strategy identified studies that were not specifically designed to influence adolescent pregnancy, but were later reported to influence any of our primary or secondary outcomes, we included such studies if they met the other eligibility criteria.

We categorised interventions as follows.

Educational interventions: health education, HIV/STD education, community services, counselling only, health education plus skills‐building, faith‐based group or individual counselling.

Contraceptive‐promoting interventions: contraception‐education with or without contraceptive distribution.

Multiple interventions: combination of educational interventions with contraceptive‐promotion interventions.

Control: no additional activity/intervention to existing conventional population‐wide activities.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Unintended pregnancy.

Secondary outcomes

Reported changes in knowledge and attitudes about the risk of unintended pregnancies.

Initiation of sexual intercourse.

Use of birth control methods

Abortion.

Childbirth.

Morbidity related to pregnancy, abortion or childbirth.

Mortality related to pregnancy, abortion or childbirth.

Sexually transmitted infections (including HIV).

Search methods for identification of studies

See: Cochrane Fertility Regulation methods used in reviews.

We did not impose any language restrictions, and sought translations where necessary. We did not impose any restrictions on journal of publication and used no country names or other geographical terms in the search. Full search strategies are shown below (Appendix 1).

Electronic searches

We searched all relevant studies regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, and in progress).

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library) online; Issue 11 November 2015.

The Cochrane Fertility Regulation Trials Search Co‐ordinator helped us to search the Group's specialised trial register (Code: SR‐FERTILREG).

We searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (1966 to November 2015), EMBASE (1980 to November 2015), Dissertations Abstracts Online (http://library.dialog.com/bluesheets/html/bl0035.html), The Gray Literature Network (http://www.osti.gov/graylit/), HealthStar, PsycINFO, CINAHL and POPLINE for randomised controlled trials using the Cochrane Fertility Regulation search strategy (Helmerhorst 2004).

We searched LILACS (La Literatura Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Informacion en Ciencias de la Salud) database 2015 (www.bireme.br; accessed November 2015) and the Social Science Citation Index and Science Citation Index (1981 to November 2015).

We searched the Specialist Health Promotion Register (Social Science Research Unit (SSRU), Institute of Education, University of London at: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk; June 2005)

For search terms, see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

In addition, we contacted individual researchers, national and international research institutes/centres and organisations (including non‐governmental organisations) working in the field of adolescent reproductive health in order to obtain information on unpublished and on‐going trials. To ensure that no relevant studies were left out, we read through the list of references in each identified study in order to follow up on articles that may have qualified for inclusion in the review.

Data collection and analysis

One hundred and forty‐two (142) potentially relevant studies were identified of which 53 studies met the inclusion criteria and two are awaiting data extraction (Studies awaiting classification) pending the collection of complete data from the study authors.

Selection of studies

Two authors (CO and EE) independently applied the inclusion criteria to all identified studies and made decisions on which studies to include. The studies were initially checked for duplicates and relevance to the review by looking at the titles and abstracts. Where it was not possible to exclude a publication by looking at the title or the abstract, the full paper was retrieved. Differences were resolved by discussion and consultation with a third author (MM, HE or JE) when in doubt. The results section of each publication was blinded during screening to minimise bias. There were no language preferences in the search or the selection of articles.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (CO and EE) undertook data extraction using a standard data extraction form. We extracted the following data from each study that qualified for inclusion in the review.

Methods: the nature of concealment of allocation to study or control group (whether adequate, unclear, inadequate, or not done), study duration, type of trial, provider and outcome assessor blinding, extent of drop‐outs and cross‐overs, co‐interventions, other potential confounders, and any validity criteria that were used.

Participants: study setting (including country, state, region, community) and unit of randomisation (schools, households, communities, faith‐based institutions), age, gender, race/ethnicity, and other socio‐demographic characteristics of participants.

Interventions: nature of the intervention delivered to the study and control groups, and how it was delivered; timing and duration, and length of follow‐up.

Outcome measures and results: differences between intervention and control groups in terms of unintended pregnancy (first pregnancy), reported knowledge and attitudes about the risk of unintended pregnancies, initiation of sexual intercourse, use of birth control methods, abortion, childbirth, morbidity related to pregnancy, abortion or childbirth, and mortality related to pregnancy, abortion or childbirth.

Missing data: missing data arose from two sources, participant attrition and missing statistics.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the methodological quality of included studies using standard methods for randomised controlled trials as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1 (Higgins 2011a).

We considered six parameters: generation of allocation sequence, concealment of allocation sequence, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias.

-

Generation of allocation sequence:

Yes ‐ if the method described was suitable to prevent selection bias (such as computer‐generated random numbers, table of random numbers or drawing lots);

Unclear ‐ if the method was not described but trial was described as "randomised"; and

No ‐ if sequences could be related to prognosis (case record number, date of birth, day, month, or year of admission).

-

Concealment of allocation:

Yes ‐ if there was evidence that the authors took proper measures to conceal allocation through, for example, centralised randomisation or use of serially‐numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes;

Unclear ‐ if the authors either did not report an allocation concealment scheme at all, or reported an approach that is unclear;

No ‐ if concealment of allocation was inadequate (such as alternation or reference to participant identification numbers or dates of birth).

-

Blinding:

Yes ‐ if there was evidence of no blinding and outcomes were unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding, or blinding of participants and key study personnel was ensured and unlikely that blinding was broken, or outcome assessment was blinded and the non‐blinding of others was unlikely to introduce bias;

Unclear ‐ insufficient information or outcome not addressed;

No ‐ no blinding and outcome likely to be influenced by lack of blinding or blinding carried out but likely to be broken.

-

Incomplete outcome data:

Yes ‐ if there is evidence that there are no missing outcome data, or reason for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome, or missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups and with similar reasons across groups, or for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically‐relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate, or for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically‐relevant impact on observed effect size, or missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods;

Unclear ‐ insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ (e.g. number randomised not stated, no reasons for missing data provided) or outcome not addressed;

No ‐ reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups or for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically‐relevant bias in intervention effect estimate, or for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size, or ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation, or potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation.

-

Selective outcome reporting:

Yes ‐ if there is evidence that all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported as stated in the protocol, or it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified in the absence of the protocol;

Unclear ‐ insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’;

No ‐ not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; or one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. sub scales) that were not pre‐specified, or one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified, or one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis, or the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study.

-

Other sources of bias:

Yes ‐ if study is free of other sources of bias;

Unclear ‐ insufficient information to assess if an important risk of bias exists or insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias;

No ‐ has extreme baseline imbalance or claimed to have been fraudulent or stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal ‐ stopping rule) or potential source of bias related to the specific study design used.

Measures of treatment effect

We performed data entry and analysis in Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3 (RevMan 2014). For meta‐analysis of categorical variables we calculated Relative Risk (RR) or Peto's Odds Ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (Cl). For meta‐analysis of continuous variables we calculated mean differences (MD).

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster randomised trials

Only cluster‐randomised trials for which adjustment had been made for design effect were included in the meta‐analyses. Where possible, we corrected for design effects using standard procedures (Rao 1992). Before entering the results of cluster‐randomised studies into RevMan, we transformed outcome data according to the procedure in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions ( Adam 2004; Deeks 2011), dividing the number of events and number of participants by the design effect [1 + (1 ‐ m) * r]. We used the details provided by each study (total n and number of clusters) to calculate the average cluster size (m). Since most of the trials did not provide the intra cluster correlation coefficient, we adopted a fairly reliable intra cluster correlation coefficient of 0.02 which had been used in a similar systematic review (DiCenso 2002).

Trials with multiple groups

Eleven studies had multiple groups ( Dilorio 2006; Downs 2004; Herceg‐Brown 1986; Jemmott 1998; Jemmott 2005; Markham 2012; Morberg 1998;, Norton 2012; O'Donnell 1999; Raine 2005, Walker 2006, ). For studies included in the meta‐analyses (Dilorio 2006; Herceg‐Brown 1986; Jemmott 1998; Morberg 1998; Raine 2005), we combined all relevant experimental intervention groups in the studies into a single group. The same was done for the control groups as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Section 16.5.4 .(Higgins 2011b) For studies with multiple follow‐up points, we used data from the last time points.

Dealing with missing data

Missing data arose from participant attrition and missing statistics.

Where possible, we extracted data by allocation intervention, irrespective of compliance with the allocated intervention, in order to allow an 'intention‐to‐treat' analysis, as this minimizes bias (Hollis, 1999); otherwise we performed an 'as‐treated' analysis. We included these variables in a meta‐analysis using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.3 for the outcomes selected above (RevMan 2014). We conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate attrition as a source of heterogeneity and possible bias.

Where statistics were missing (numbers of participants per group, attrition rates, percentage affected for each outcome), we contacted primary study authors to supply the information. Where the information was unavailable due to data loss or non‐response, we reported the available results as stated in the trial report in the Additional table (Table 5).

1. Studies that Could not be included in meta‐analysis.

| Intervention | Outcome | Study ID | Number Assessed | Case affected | Control affected | Test Statistics | 95% CI | p‐value |

| Educational intervention | Pregnancy | Mitchell‐DiCenso 1997 | 1701 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 0.97 | 0.93 to 1.0 | 0.04 |

| Initiation of intercourse | Clark 2005 | 156 | ‐ | ‐ | Beta: 1.604 and SE: 1.00 | ‐ | < 0.11 | |

| Aarons 2000 (females) | 139 | Adj. OR: 1.88 | 1.02 to 3.47 | 0.04 | ||||

| Aarons 2000 (males) | 123 | Adj. OR: 1.18 | 0.61 to 2.29 | 0.62 | ||||

| Perskin 2015 | 1079 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 1.00 | 0.70 to 1.41 | |||

| Changes in knowledge and attitudes about the risk of unintended pregnancy | Blake 2001 | 351 | 92.9% | 91.8% | ns | |||

| Use of birth control at last sex | Mitchell‐DiCenso 1997 (females) | 109 | 42.2% | 46.7% | OR: 1.03 | 1.00 to 1.07 | 0.03 | |

| Mitchell‐DiCenso 1997 (males) | 214 | 39.3% | 35.9% | OR: 1.06 | 1.02 to 1.77 | 0.005 | ||

| Aarons 2000 (females) | 135 | Adj. OR: 3.39 | 1.16 to 9.95 | 0.025 | ||||

| Aarons 2000 (males) | 125 | Adj. OR: 1.53 | 0.55 yo 4.26 | 0.42 | ||||

| Use of condom at last sex | Okonofua 2003 | 1896 | 39.1% | 31.9% | OR: 1.41 | 1.12 to 1.77 | ‐ | |

| Clark 2005 | 221 | 77% | 73% | |||||

| Unprotected intercourse in the past 3 monthsa | Kogan 2012 | 502 | Beta: ‐0.375 and SE: 0.32 | >0.05 | ||||

| Ever had sex without condoms | Dilorio 2007 | Mean: 0.23 | Mean: 0.57 | ‐0.61 to ‐0.06 | 0.03 | |||

| Multiple interventions | Pregnancy | Coyle 2006 | 308 | ‐ | ‐ | OR; 0.84 | ‐ | 0.61 |

| Diclemente 2004 | 460 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 0.53 | 0.27 to 1.03 | 0.06 | ||

| Stephenson 2004b | 1172 | 2.3% | 3.3% | ‐ | ‐ | 0.07 | ||

| Kirby 2004 | 2145 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 1.34 | 0.98 to 1.84 | 0.07 | ||

| Coyle 2006 | 417 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 0.77 | 0.49 to 1.23 | 0.28 | ||

| Smith 1994 | 95 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | < 0.05 | ||

| O'Donnell 2002 | 195 | 6.8% | 18.5% | |||||

| Morrison‐Beedy 2013 | 323 | B=‐.823 OR: 0.44 |

0.009 | |||||

| Allen 1997 | 560 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 0.41 | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Initiation of sexual intercourse (mixed gender) | Coyle 2006 | 94 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 1.23 | 0.51 to 2.97 | 0.65 | |

| Smith 1994 | 95 | .Mean: 1.19 | .Mean: 2.74 | |||||

| Basen‐Engquist 2001 | 8326 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 1.03 | 0.88 to 1.21 | 0.69 | ||

| Markham 2012 | 627 | AOR:0.65 | 0.54,0.77 | <.01 | ||||

| O'Donnell 2002 | 195 | 40.1% | 66.1% | OR: 0.39 | 0.20 to 0.76 | 0.005 | ||

| Markham 2012 | 735 | AOR:0.82 | 0.51,1.34 | >0.05 | ||||

| Coyle 1999 | 2565 | OR:1.13 SE: 0.24 |

0.71 to 1.82 | 0.60 | ||||

| Initiation of sexual intercourse (male) | Coyle 2004 | 1412 | 19.3% | 27.7% | model R2: 0.118 | ‐ | 0.02 | |

| Kirby 2004 | 809 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 1.08 | 0.80 to 1.46 | 0.63 | ||

| Stephenson 2004 | 8156 | 32.7% | 31.1% | OR: 0.90 | 0.65 to 1.23 | 0.35 | ||

| Eisen 1990 | 408 | 36% | 44% | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Initiation of sexual intercourse (female) | Coyle 2004 | 1417 | 20.3% | 22.1% | model R2: 0.145 | ‐ | 0.53 | |

| Kirby 2004 | 1220 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 0.88 | 0.59 to 1.31 | 0.54 | ||

| Stephenson 2004 | 8156 | 34.7% | 40.8% | OR: 0.80 | 0.66 to 0.97 | 0.008 | ||

| Eisen 1990 | 480 | 27% | 22% | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Use of condoms at last sex | Kirby 2004 | 2145 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 1.38 | 1.06 to 1.79 | 0.02 | |

| Coyle 2006 | 359 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 1.00 | 0.49 to 1.23 | 0.99 | ||

| Diclemente 2004 | 460 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 3.94 | 2.58 to 6.03 | < .001 | ||

| Downs 2004 | 258 | ‐ | ‐ | OR: 2.13 | ‐ | 0.15 | ||

| Norton 2012 | 198 | OR: 0.93 | ‐0.75,0.62 | 0.85 | ||||

| Coyle 1999 | 1018 | OR:191 SE:0.27 |

1.13 to 3.21 | 0.02 | ||||

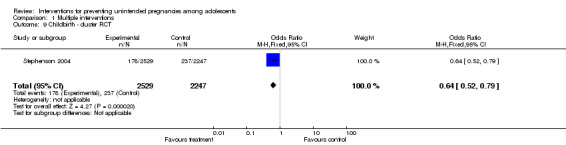

| Childbirth | Henderson 2007 | 4196 | 300/1000 | 274/1000 | OR: 14.6 | 0.32 | ||

| Abortion | Henderson 2007 | 4196 | 127/1000 | 112/1000 | OR: 26.4 | 0.40 | ||

| Consistent condom use at 12 months | Sieving 2011 | 253 | Mean: 0.96 (116/126) | Mean: 0.66 (81/127) | ARR:145 | 1.26 to 1.67 | 0.00 | |

| Consistent condom use at 24 months | Sieving 2011 | 204 | Mean:1.53 | Mean: 0.93 | ARR: 1.57 | 1.28,1.94 | ||

| Consistent hormonal contraceptive use at 12 months | Sieving 2011 | 253 | Mean: 4.27 (74/126) | Mean: 2.91 (51/127) | ARR:1.46 | 1.13 to 1.89 | 0.00 | |

| Consistent hormonal contraceptive use at 24 months | Sieving 2011 | 203 | Mean: 3.29 | Mean: 2.34 | ARR: 1.30 | 1.06,1.58 | ||

| Minnis 2014 | 162 | OR:0.42 | 0.12 | |||||

| Use of condoms at first sex | Coyle 1999 | 285 | OR:0.68 SE:0.48 |

0.26 to 1.75 | 0.42 | |||

| Protected against pregnancy at last sex | Coyle 1999 | 998 | OR:1.62 SE:0.22 |

1.05 to 2.50 | 0.03 | |||

| Sexually Transmitted Infections | Morrison‐Beedy 2013 | 323 | B=‐0.067 OR: ‐0.94 |

0.77 | ||||

| Jemmott 2005c | Mean:10.5 SE: 2.9 |

Mean:18.2 SE:2.8 |

0.05 | |||||

|

Baird 2010: The following listed outcomes were reported. However, the method of reporting made difficult to extract correct estimates. 1. Pregnancy School girls and dropouts among the treatment group are 1.1 percentage points less likely to have become pregnant over the past year. Not statistically significant. 2. Onset of sexual intercourse There was a 46.6% reduction in the onset of sexual activity among initial dropouts (P < 0.01) and a 31.3% reduction in the onset of sexual activity among initial schoolgirls (P = 0.112). 3.Condom use The intervention had no impact on self‐reported condom use. | ||||||||

a ‐ Binary outcome (did unprotected intercourse occur or not?)

b ‐ Study (Stephenson 2008) same as Stephenson 2004, but with an extended follow up (7yrs)

c ‐ Data comparing skills‐based intervention versus health‐promotion intervention

Analyses assessing impact on delay of sexual initiation excluded individuals who reported any type of sexual intercourse at baseline

Analyses assessing impact on other on sexual behaviours are limited to individuals that are sexually active

ns ‐ non‐significant

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed data sets for heterogeneity by visual assessment of forest plots and chi2 tests for heterogeneity with a 10% level of statistical significance, and applied the I2 statistic with a value of 50% or higher denoting significant levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Since asymmetry of funnel plots may result from publication bias, heterogeneity, or poor methodological quality (Sterne 2011), we planned to examine funnel plots using Review Manager 5.3 but found an insufficient number of trials to do this.

Data synthesis

We used a fixed‐effects model (FEM) for data synthesis and a random‐effects model (REM) for cases where we detected heterogeneity, and considered it appropriate to still perform meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

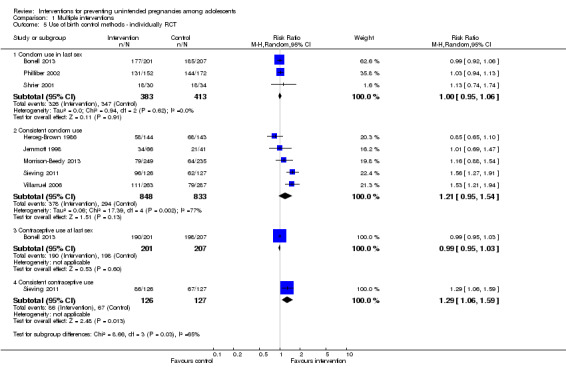

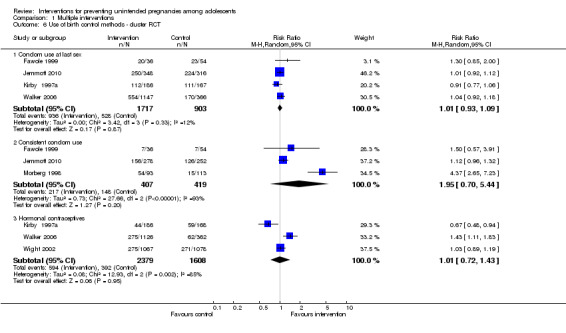

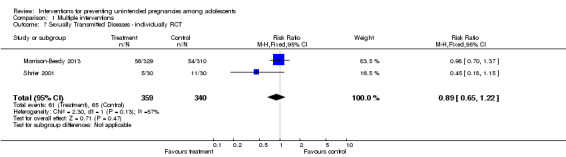

We sub‐grouped the use of birth control into 'condom use at last sex', 'consistent condom use', 'contraceptive use at last sex', 'consistent contraceptive use' and 'use of hormonal contraceptive'. We found insufficient data to conduct sub‐group analysis of homosexual and heterosexual intercourse. We excluded quasi‐experimental studies (controlled before‐and‐after, and interrupted time series) as this was cumbersome and would have delayed the update of this review.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome (unintended pregnancy) including and excluding trials with high attrition rates (> 20%). The number of trials that used adequate allocation concealment was insufficient to allow for sensitivity analysis to assess the possible influence of high risk of bias in trials that did not apply allocation concealment.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We found 142 studies, of which we included 53 and excluded 87 , with two awaiting assessment (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification); we have approached the primary authors of these papers for relevant additional information.

Included studies

All the studies were randomised controlled trials. Eighteen of the studies randomised individuals, 32 randomised clusters (schools (20), classrooms (6), and communities/neighbourhoods such as community‐based organisations and social networks (6). Three studies were mixed (individually and cluster randomised) (Allen 1997; Eisen 1990; Kirby 1997b). The length of follow up varied from three months to seven years, with greater than 12 months being the most common duration.

Participants

A total of 105,368 participants were included in all the included studies. The number of participants per study varied greatly (Characteristics of included studies). Most of the studies confined inclusion of participants to specific age requirements, others restricted inclusion based on specific school grade levels (varying between 6th grade to 12th grade). The age of participants in the included studies ranged from 9 years to 19 years, except for seven studies which included participants aged 9 years to 24 years: Baird 2010, 13 years to 22 years; Mba 2007, 10 years to 20 years; Minnis 2014, 16 years to 21 years; Okonofua 2003, 14 years to 20 years; Raine 2005, 15 years to 24 years (mean 19.9); Raymond 2006, 14 years to 24 years; and Shrier 2001, 13 years to 22 years (median 17). For these studies, more than 75% of the participants were within the stipulated age limit of 10 years to 19 years. Sixteen studies included participants who were sexually active (Baird 2010; Bonell 2013; Diclemente 2004; Downs 2004; Jemmott 2005, Jemmott 2010; Kogan 2012; Markham 2012; Mba 2007; Minnis 2014; Morrison‐Beedy 2013; Norton 2012; O'Donnell 1999; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Sieving 2011); one study recruited adolescent mothers < 18 years at time of delivery living with their mothers (Black 2006); three studies recruited dyads (adolescents and their guardian) (Dilorio 2006; Dilorio 2007; Guilamo‐Ramos 2011b). Most studies included male and female participants. Eighteen studies included female participants only (Allen 1997; Baird 2010; Black 2006; Bonell 2013; Cabezon 2005; Diclemente 2004; Downs 2004; Ferguson 1998; Guilamo‐Ramos 2011b; Henderson 2007; Herceg‐Brown 1986; Howard 1990; Jemmott 2005; Morrison‐Beedy 2013; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; , Shrier 2001; Sieving 2011) and one, male participants only (Dilorio 2007).

Setting

Four trials were conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Baird 2010; Fawole 1999; Mba 2007; Okonofua 2003), and all others were conducted in high‐income countries: United States of America (41), England (2), Scotland (2), Canada (1), Italy (1) and Mexico (2). Most of the studies were conducted in schools. Other sites included hospitals or family planning health agencies, neighbourhoods/communities and clubs.

Interventions

Educational interventions

Six studies compared an educational interventions to a standard school curriculum (control): Aarons 2000; Blake 2001; Clark 2005; Dilorio 2007 (parent‐based educational intervention); Mitchell‐DiCenso 1997; and Perskin 2015 (computer‐based sexual health education). Three studies compared the intervention to regular health promotion classes or no control intervention (Kogan 2012; Mba 2007; Okonofua 2003). One study offered the same intervention to the two groups but with different instructors (peers or teachers) (Borgia 2005). Another study compared a parent‐based intervention based on social cognitive theory (intervention 1) and a life skills programme based on problem behaviour theory (intervention 2) versus a one‐hour HIV‐prevention session (control) (Dilorio 2006);

Contraceptive‐promoting interventions

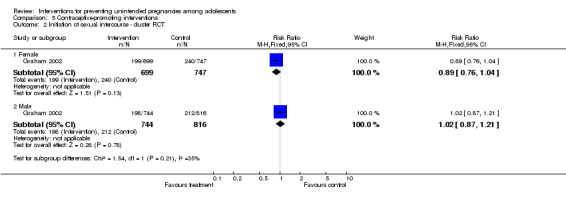

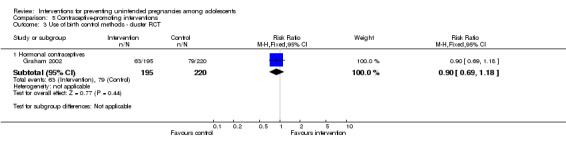

Two studies compared the effect of improving access to contraception. Raine 2005 had two intervention groups (pharmacy access and advance provision of contraceptives) and a control (clinic access, as needed); Raymond 2006 compared increased access to contraceptives (unlimited free supply) versus standard access (as needed, at usual cost). Another study compared contraception education to usual school sex education (Graham 2002).

Multiple interventions (educational and contraceptive‐promoting interventions)

Twelve studies compared a combination of educational interventions and contraceptive‐promoting interventions with standard school curriculum (sex or HIV/AIDS education) (Basen‐Engquist 2001; Coyle 1999; Coyle 2004; Coyle 2006; Eisen 1990; Fawole 1999; Henderson 2007; Howard 1990; Kirby 1997a; Kirby 2004; Shrier 2001; Wight 2002). Sieving 2011 compared multiple interventions linked to clinical services versus usual clinical service only for 17 months and 24 months, and Bonell 2013 compared weekly three‐hour sessions over 18 weeks to 20 weeks in pre‐school nurseries developing parenting, self‐awareness and confidence versus health promotion only . Three studies added community youth services to their intervention versus the following control groups: regular health curriculum (Allen 1997) and standard class curriculum (O'Donnell 1999; O'Donnell 2002).

Four studies compared multiple interventions with health promotional interventions unrelated to sexual behaviour, or no intervention for the control groups (Cabezon 2005; Diclemente 2004; Morrison‐Beedy 2013; Villarruel 2006 ). One study offered written materials on the lessons covered in the intervention programme to the control group (Smith 1994).

Nine studies compared more than one intervention (multiple intervention groups). Jemmott 1998 had two interventions, one with an emphasis on abstinence versus one with an emphasis on the use of contraceptives, compared to a health promotion control. Jemmott 2005 compared the same intervention (informative versus skills‐based (practical) versus health promotion (control). Kirby 1997b compared an adult‐led intervention versus a youth‐led intervention (each with the same contents) compared to the standard sex curriculum. Markham 2012 compared risk avoidance (abstinence until marriage) versus risk reduction (with the emphasis on abstinence until older) versus a control of regular health classes. Morberg 1998 compared a four‐week intervention over three years in one intervention group and a 12‐week intervention over one year in the other, versus the usual school curriculum. Walker 2006 used the same intervention for both intervention groups but one emphasised the use of condoms and the other emphasised access to condoms and emergency contraceptives, versus biology‐based sex education.. . . Two studies compared three intervention groups with different aims. Jemmott 2010 compared three different levels of training: enhanced training (intervention package, two days' training plus hands‐on training/practice); standard training (intervention package plus two days' training); and manual only (intervention package provided to participants but no training) compared to non‐sexual‐related health promotion intervention (control). Norton 2012 compared the promotion of condom use to prevent an unplanned pregnancy (pregnancy intervention), STI (STI intervention), and HIV (HIV intervention), versus standard health services received by students. . Herceg‐Brown 1986 had two intervention groups, regular clinic services plus 50 minutes of family or individualised counselling services on sex and contraceptive education for six weeks known as the 'Family support group', versus regular clinic services plus staff support through two to six telephone calls four to six weeks after the initial clinic visit, known as the 'Periodic support group', versus regular clinic services.

One study, Downs 2004 had one intervention and two control groups. The same information was provided to the control groups as to the intervention group, however they differed in their mode of administration (interactive video versus book form or brochure for the controls). Another study, Guilamo‐Ramos 2011b evaluated a parent‐based intervention (health education and skills‐building); parents and their adolescent children participated in the intervention, versus standard health promotion for nine months.

Two studies offered some form of incentive to the intervention group; Minnis 2014 combined conditional cash transfers (CCT) as an incentive for completing educational, reproductive health and life skills sessions; while Baird 2010 provided CCT (an incentive for schoolgirls and dropouts to stay in school or return to school respectively), with the aim of reducing certain sexual behaviours.

One study offered peer‐led multiple interventions versus usual teacher‐led sex education (Stephenson 2004), while another compared same intervention administered by peer counsellors compared to adult staff (Ferguson 1998).

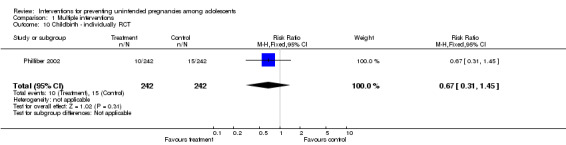

One study compared the intervention with an alternative youth programme (recreational activities, art & crafts) (Philliber 2002).

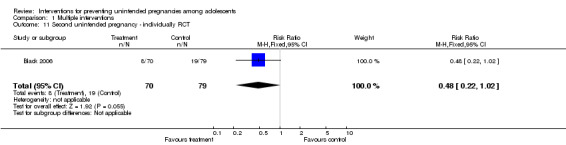

Black 2006 aimed to prevent a second unintended pregnancy. The intervention involved a home‐mentoring programme (home visits every week until the infant's first birthday, approximately 19 visits) compared to a no‐intervention control ().

Outcomes

Twenty studies assessed and reported on unintended pregnancy (Allen 1997; Bonell 2013; Cabezon 2005; Coyle 2006; Diclemente 2004; Ferguson 1998; Herceg‐Brown 1986; Howard 1990; , Kirby 1997a; Kirby 1997b; Kirby 2004; Mitchell‐DiCenso 1997; Morrison‐Beedy 2013; O'Donnell 2002; Philliber 2002; , Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Smith 1994; Stephenson 2004; Wight 2002 , , , , ) and one study reported second unintended pregnancy (Black 2006). Other outcomes reported were initiation of intercourse, consistent use of contraceptives or condoms, use of contraceptives or condoms at last sex, use of hormonal contraceptives, knowledge about the risk of pregnancy, abstinence, sexually transmitted diseases, childbirth and abortion.

Most studies reported outcomes on the change in knowledge of STD, HIV, AIDS, condom and contraceptive use, as well as intentions to use condoms, contraceptives or have sex. However, these were not part of the outcomes assessed in this review and therefore were not reported.

Excluded studies

Eighty‐four studies were excluded; forty‐six studies, though randomised studies were excluded for one or more of the following reasons: none of the desired outcomes was measured, participants were either pregnant or couples, more than 25% of the participants were above the required age range, the study did not use the desired intervention, there was no formal control group, had no protocol, and the stated method of randomisation was not adequate. The remaining studies (38) were not randomised controlled studies (Characteristics of excluded studies).

No ongoing studies were found.

Risk of bias in included studies

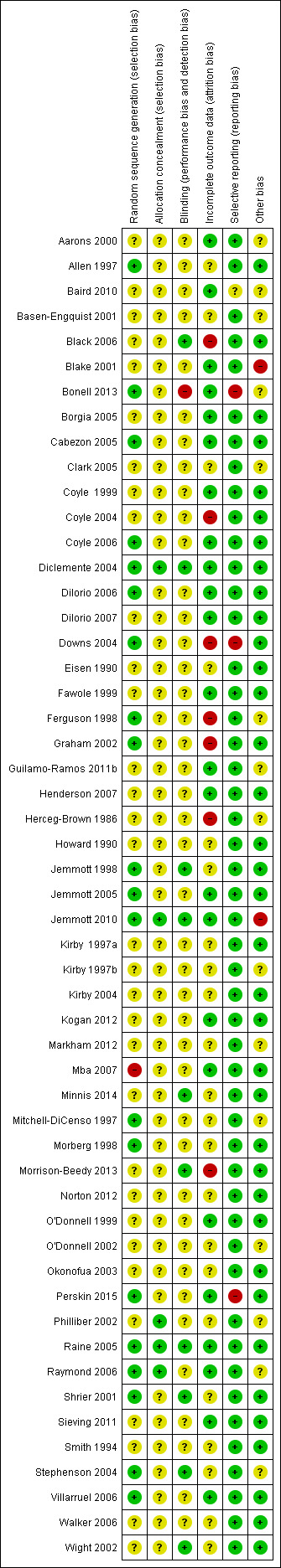

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Generation of allocation sequence: ten studies used a computer‐generated allocation sequence (Bonell 2013; Dilorio 2006; Graham 2002; Jemmott 1998; Jemmott 2005; Jemmott 2010; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006; Stephenson 2004; Villarruel 2006), four used a table of random numbers (Diclemente 2004; Downs 2004; Mitchell‐DiCenso 1997, Shrier 2001), one used simple balloting (Cabezon 2005), two used coin toss technique (Allen 1997; Ferguson 1998). Two trials used restricted randomisation involving multiple steps (Coyle 2004, Coyle 2006), and two other studies used block randomisation (Morberg 1998; Philliber 2002,). One trial reported use of "balanced randomisation" (Wight 2002) but gave no details to explain the procedure, and another one used quarterly marking period within school (Blake 2001). One study used a modified "multi‐attribute randomization method", providing no further details (Perskin 2015). The remaining studies (29) had insufficient or no information on the randomisation generation method, and used terms such as "assigned at random" or "randomly assigned", leaving us uncertain whether the trial results were vulnerable to selection bias.

Allocation concealment: four studies reported adequate allocation concealment that used sealed, opaque envelopes (Diclemente 2004; Philliber 2002; Raine 2005; Raymond 2006). The remaining studies did not provide information on concealment of allocation.

Baseline differences can be increased by inadequate and clustered randomisation sequences. Out of the 53 trials, 17 reported at least one significant group difference at baseline (Aarons 2000; Allen 1997; Basen‐Engquist 2001; Coyle 2004; Coyle 2006; Dilorio 2006; Jemmott 1998; Jemmott 2005; Jemmott 2010; Kirby 1997b; Markham 2012; Mitchell‐DiCenso 1997; Morberg 1998; Okonofua 2003; Raymond 2006; Smith 1994 ) and each one of these trials controlled for baseline differences in analyses. One study Mba 2007, did not test for baseline differences between groups.

Three trials did not report a clear statement of baseline differences between groups (Dilorio 2007; Ferguson 1998; Henderson 2007) but controlled for these differences in their analyses. One trial used a significance level of P < 0.01 for these calculations (Kirby 1997a), and two reported baseline differences only for sexual behaviours (Clark 2005; O'Donnell 2002).

Blinding

For most of the trials, staff (assessors and administrators) were not blinded to group assignment, as every trial utilised written self‐reported questionnaires, although assessor blinding was reported in eight studies (Black 2006; Bonell 2013; Diclemente 2004; Jemmott 1998; Raine 2005; Shrier 2001; Stephenson 2004; Wight 2002 ). Two studies blinded participants and interviewers (Jemmott 2010; Minnis 2014). For one study, the condition was unknown to participant and facilitators until groups were filled and facilitators assigned (Morrison‐Beedy 2013) and for another, the condition was unknown only to participants until after baseline assessment (Perskin 2015). Blinding was not reported in the remaining 42 studies. The impossibility of blinding intervention staff may have given rise to performance bias.

Contamination or 'exchange of information' of the control group might have occurred as the intervention and control groups sometimes attended different programmes at the same site. This is more likely to be present in trials that randomised participants by individual or classroom, rather than by entire community centre, school or neighbourhood. This, however, leads to bias in the findings in the direction of no effect rather than in the direction of significance.

Incomplete outcome data

Attrition rates at final follow‐up ranged from 0.5% (Henderson 2007) to 58% (Coyle 2006). Five studies did not clearly explain/state the numbers of individuals lost to follow up (Baird 2010; Basen‐Engquist 2001; Blake 2001; Howard 1990; Norton 2012). Eighteen trials reported overall attrition rates that exceeded 20% at final follow up (Borgia 2005; Clark 2005; Coyle 2004; Coyle 2006; Dilorio 2007; Eisen 1990; Jemmott 2010; Kirby 1997a; Kirby 2004; Markham 2012; Mitchell‐DiCenso 1997; Morberg 1998; O'Donnell 2002; Philliber 2002; Shrier 2001; ,Smith 1994; Stephenson 2004; Walker 2006 , . ).

Most trials conducted a modified intention‐to‐treat analysis (whereby all students were included in the analysis regardless of number of sessions attended as long as they provided baseline and follow‐up data). Outcomes such as pregnancy, use of condoms, contraceptive and sexually transmitted diseases were analysed using the number who initiated sex or were already sexually active as the sample size (denominator). Coyle 2004 made use of a rich‐imputation model based on baseline peer norms, group, time, ethnicity, and group‐by‐time interaction to account for dropouts. O'Donnell 2002 conducted several sets of analyses according to different principles: not reporting results according to original dropouts.

Studies with outcomes that could not be included in the meta analysis are reported in Table 5.

Selective reporting

Apart from the primary outcome, most included studies reported a range of outcomes (sexual behaviour), using different recall periods and grouping outcomes such as initiation of intercourse at three months and six months, and use of condoms at last sex, thus suggesting no standard set of outcomes for evaluation, preventing a comprehensive meta‐analysis.

Results were also analysed based on subgroups of participants, for example, measuring initiation of intercourse among virgins and non‐virgins at baseline. However, more often, sexual initiation was often assessed only among participants who reported never having had sexual intercourse at baseline.

Few studies reported at least one outcome separately by gender without providing overall summaries of effect (Aarons 2000; Coyle 2004; O'Donnell 2002).

Due to missing information such as numbers of participants per trial arm and percentages for dichotomous outcomes, meta‐analysis could not be carried out for some studies (data presented in Table 5).

The lack of statistical controls for cluster‐randomised data, is a limitation for this study. While most cluster randomised studies controlled for clustering in their analyses, some did not (Aarons 2000; Allen 1997; Fawole 1999; Kirby 1997a), suggesting that studies which did not report statistical methods for dealing with clustered data analysed their results on an individual level.

Few studies attempted to control for the occurrence of a Type I error which is likely to occur when different outcomes are analysed; Allen 1997 and Raine 2005 used a Bonferroni correction when considering the significance of statistical tests, and Coyle 2004 stated it use though the method was not specified.

Other potential sources of bias

Limitations of self‐report and behavioural outcome data

Most of the studies made use of self‐reported data which is an inevitable source of bias for studies evaluating sexual behaviours (as there is the tendency for respondents to agree with statements associated with healthier behaviours or attitudes). However, the veracity of the self‐reported behaviours was improved by privacy and confidentiality in most studies.

Heterogeneity in programme design and implementation across trials

A major source of bias in this review is a high degree of heterogeneity in the ways programmes were designed and implemented across trials. This can be seen in some of the meta‐analyses carried out. Our inclusion criteria specified that we would accept interventions that aimed to prevent unintended pregnancy while promoting safer‐sex strategies such as condom use or contraceptive use but it is unclear how much emphasis was put on these goals. An example is Eisen 1990 that offered almost the same intervention to both groups differing only in the level of emphasis and duration of the intervention, or studies offering same intervention but administered differently such as peer‐counsellor facilitators versus adult staff (Ferguson 1998) and Downs 2004, interactive video versus book form or brochure of the same intervention.

Finding relevant trials

Though the search for relevant trials was comprehensive, it is likely that relevant trials may have been omitted from this review, if the specified search terms were not mentioned in the title and abstracts but most likely due to inability to assess all unpublished trials.

Underreporting of implementation data

Inadequate description of programme design and implementation made the assessment of heterogeneity challenging. Differences in the way that programmes were designed, delivered, and taken up may have made the studies too heterogeneous to permit comparisons across trials; however, these differences are difficult to determine from the available data and could have influenced the meta‐analyses. Few studies reported strategies to monitor and promote the extent to which programmes were delivered by facilitators and taken up by participants as planned. Such strategies include take‐home assignments, keeping attendance records, conducting interviews with programme staff and participants, bringing in independent raters (Morrison‐Beedy 2013), conducting exit interviews with participants, and communication with participants by phone (Herceg‐Brown 1986, Dilorio 2006). One study regularly trained all programme staff, visiting each site regularly (Philliber 2002). Though these strategies were put in place, most trials rarely stated the extent of implementation fidelity. One study Morberg 1998, reported difficulties for community‐based programme activities to convey programme messages related to sexual behaviour due to vocal opposition; at one programme site, a member of the community opposition group attended every programme session related to sexual behaviour, potentially affecting programme delivery.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

for the main comparison.

| Contraceptive‐promoting interventions (individual RCTs) | |||||

| Patient or population: Male and female adolescents aged 10 years to 19 years Setting: All settings Intervention: Contraceptive‐ promoting interventions Comparison: No additional activity/intervention to existing conventional population‐wide activities | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with No intervention/standard curriculum | Risk with Contraception Intervention | ||||

| Unintended pregnancy follow up: range 6 months to 12 months | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.81 to 1.26) | 3440 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| 83 per 1000 | 84 per 1000 (67 to 105) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 85 per 1000 | 86 per 1000 (69 to 107) | ||||

| Use of birth control methods (condom use in last sex) follow up: range 6 months to 12 months | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.87 to 1.04) | 3091 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| 367 per 1000 | 348 per 1000 (319 to 381) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 312 per 1000 | 296 per 1000 (271 to 324) | ||||

| Use of birth control methods (hormonal contraceptives) follow up: range 6 months to 12 months | Study population | RR 2.22 (1.07 to 4.62) | 3091 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| 165 per 1000 | 365 per 1000 (176 to 760) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 131 per 1000 | 292 per 1000 (141 to 607) | ||||

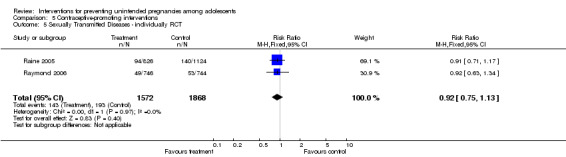

| Sexually Transmitted Diseases follow up: range 6 months to 12 months | Study population | RR 0.92 (0.75 to 1.13) | 3440 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| 103 per 1000 | 95 per 1000 (77 to 117) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 98 per 1000 | 90 per 1000 (73 to 111) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: confidence interval fail to appreciable harm and included the null value

2.

| Educational interventions (cluster RCTs) | |||||

| Patient or population: Male and female adolescents aged 10 years to 19 years Setting: All settings Intervention: Educational interventions Comparison: No additional activity/intervention to existing conventional population‐wide activities | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with No intervention/Standard curriculum | Risk with Educational intervention | ||||

| Use of birth control methods (condom use at last sex) follow up: range 5 months to 24 months | Study population | RR 1.18 (1.06 to 1.32) | 1431 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| 261 per 1000 | 308 per 1000 (277 to 345) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 534 per 1000 | 630 per 1000 (566 to 704) | ||||

| Initiation of sexual intercourse (mixed gender) follow up: range 12 months to 24 months | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.71 to 1.27) | 672 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| 227 per 1000 | 215 per 1000 (161 to 288) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Several risk of bias assessment were unclear (not provided in the text)

2 Low number of events and confidence interval includes the null value

3.

| Multiple interventions (cluster RCTs) | |||||

| Patient or population: Male and female adolescents aged 10 years to 19 years Setting: All settings Intervention: Multiple interventions Comparison: No additional activity/intervention to existing conventional population‐wide activities | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with No Intervention/Standard curriculum | Risk with Multiple interventions | ||||

| Unintended pregnancy follow up: range 3 months to 48 months | Study population | RR 0.50 (0.23 to 1.09) | 3149 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 3 | |

| 67 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (15 to 73) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 25 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (6 to 27) | ||||

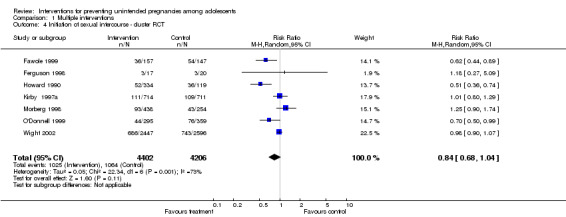

| Initiation of sexual intercourse (mixed gender) follow up: range 3 months to 36 months | Study population | RR 0.84 (0.68 to 1.04) | 8608 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 5 | |

| 253 per 1000 | 212 per 1000 (172 to 263) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 212 per 1000 | 178 per 1000 (144 to 220) | ||||

| Use of birth control methods (condom use at last sex) follow up: range 6 months to 17 months | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.93 to 1.09) | 2620 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 6 | |

| 585 per 1000 | 591 per 1000 (544 to 637) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 565 per 1000 | 570 per 1000 (525 to 615) | ||||

| Use of birth control methods (consistent condom use) follow up: range 6 months to 36 months | Study population | RR 1.95 (0.70 to 5.44) | 826 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 7 | |

| 353 per 1000 | 689 per 1000 (247 to 1000) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 133 per 1000 | 259 per 1000 (93 to 722) | ||||

| Use of birth control methods (hormonal contraceptives) follow up: range 16 months to 24 months | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.72 to 1.43) | 3987 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 5 7 | |

| 244 per 1000 | 246 per 1000 (176 to 349) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 251 per 1000 | 254 per 1000 (181 to 360) | ||||

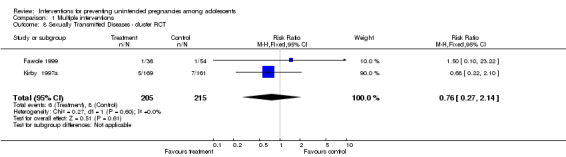

| Sexually Transmitted Diseases follow up: range 6 months to 17 months | Study population | RR 0.76 (0.27 to 2.14) | 420 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 8 | |

| 37 per 1000 | 28 per 1000 (10 to 80) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 31 per 1000 | 24 per 1000 (8 to 66) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Downgraded by 1 for risk of bias; several assessments were unclear due to no information provided. Such potential limitations are likely to lower confidence in the estimate of effect

2 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision; low number of events, confidence interval includes appreciable benefit and null value

3 Heterogeneity could be explained (difference in comparison intervention and length of follow up)

4 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: confidence interval includes appreciable benefit

5 Downgraded by 1 for inconsistency: unexplained large variations in effect

6 Confidence interval includes the null value, however, the sample size and number of events are fairly large and confidence interval is relatively narrow

7 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: confidence interval includes appreciable benefit and harm

8 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision; low number of events, confidence interval includes appreciable benefit and harm

4.

| Multiple interventions ( individual RCTs) | |||||

| Patient or population: Male and female adolescents aged 10 years to 9 years Setting: All settings Intervention: Multiple interventions Comparison: No additional activity/intervention to existing conventional population‐wide activities | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with No Intervention/Standard curriculum | Risk with Multiple interventions | ||||

| Unintended pregnancy follow up: range 12 months to 36 months | Study population | RR 0.66 (0.50 to 0.87) | 1905 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| 116 per 1000 | 76 per 1000 (58 to 101) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 149 per 1000 | 98 per 1000 (74 to 129) | ||||

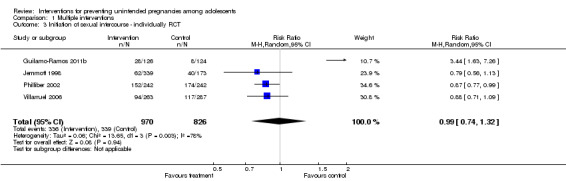

| Initiation of sexual intercourse (mixed gender) follow up: range 9 months to 36 months | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.74 to 1.32) | 1796 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| 410 per 1000 | 406 per 1000 (304 to 542) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 236 per 1000 | 234 per 1000 (175 to 312) | ||||

| Use of birth control methods (condom use in last sex) follow up: range 12 months to 24 months | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) | 796 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 6 | |

| 840 per 1000 | 840 per 1000 (798 to 891) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 837 per 1000 | 837 per 1000 (795 to 887) | ||||

| Use of birth control methods (consistent condom use) follow up: range 12 months to 24 months | Study population | RR 1.21 (0.95 to 1.54) | 1681 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 5 6 | |

| 353 per 1000 | 427 per 1000 (335 to 544) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 476 per 1000 | 575 per 1000 (452 to 732) | ||||

| Sexually Transmitted Diseases follow up: mean 12 months |

Study population | RR 0.89 (0.65 to 1.22) | 699 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 5 8 | |

| 191 per 1000 | 170 per 1000 (124 to 233) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 270 per 1000 | 241 per 1000 (176 to 330) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Downgraded by 1 for risk of bias; several assessments were unclear due to no information provided. Such potential limitations are likely to lower confidence in the estimate of effect

2 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision; low number of events, confidence interval includes appreciable benefit and null value

3 Heterogeneity could be explained (difference in comparison intervention and length of follow up)

4 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: confidence interval includes appreciable benefit

5 Downgraded by 1 for inconsistency: unexplained large variations in effect

6 Confidence interval includes the null value, however, the sample size and number of events are fairly large and confidence interval is relatively narrow

7 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision: confidence interval includes appreciable benefit and harm

8 Downgraded by 1 for imprecision; low number of events, confidence interval includes appreciable benefit and harm

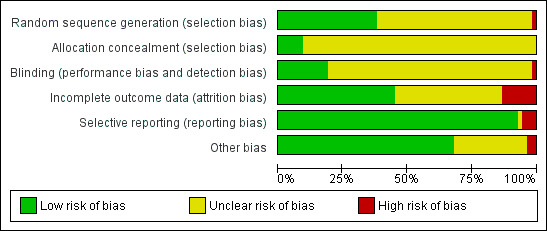

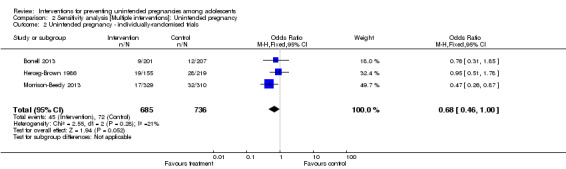

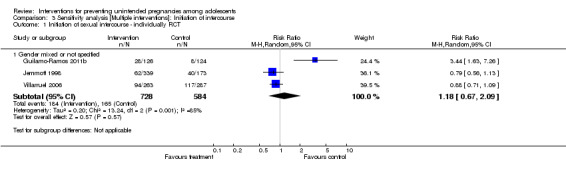

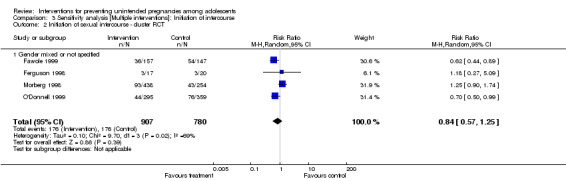

MULTIPLE INTERVENTIONS

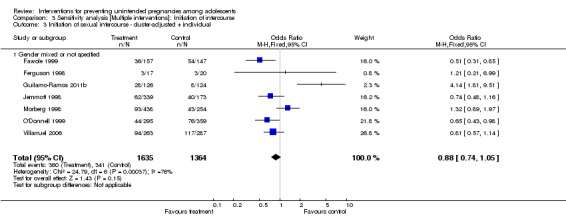

Unintended pregnancy

Four individually randomised trials (Bonell 2013; Herceg‐Brown 1986; Morrison‐Beedy 2013; Philliber 2002), showed that risk of unintended pregnancy was significantly lower among participants that received multiple interventions compared with the control group; (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.87; 4 studies; 1905 participants, Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Multiple interventions, Outcome 1 Unintended pregnancy [individually randomised trials].

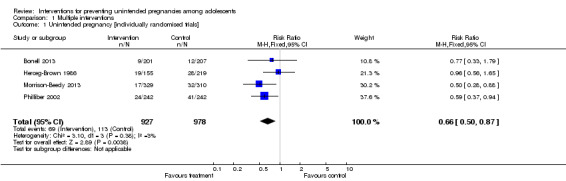

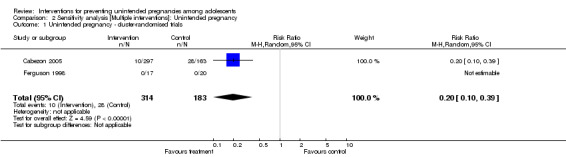

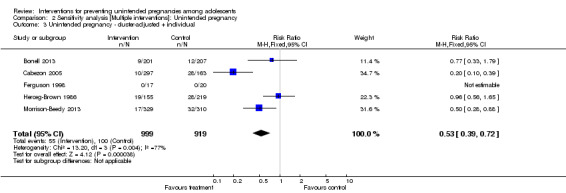

Five cluster trials (Cabezon 2005; Ferguson 1998; Howard 1990; Kirby 1997b; Wight 2002) that adjusted for design effect showed a 50% reduction in the risk of unintended pregnancy in the intervention group compared to the control group, although the difference was not statistically significant ((RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.09; 5 studies, 3149 participants, Analysis 1.2). However sensitivity analysis excluding trials with high attrition rates showed that the risk of unintended pregnancy was significantly lower in the intervention than control groups ((RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.39; 2 studies, 497 participants, Analysis 2.1). In addition, an analysis that combined cluster‐randomized trials (adjusted for design effect) with individually randomised trials (Bonell 2013; Cabezon 2005; Ferguson 1998; Herceg‐Brown 1986; Morrison‐Beedy 2013 ) showed significantly lower risk of unintended pregnancy in the intervention group compared to control (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.72; 5 studies,1918 participants,Analysis 2.3 ). This sensitivity analysis showed a persistence of statistical heterogeneity with I2 statistic of 77% (Analysis 2.3).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Multiple interventions, Outcome 2 Unintended pregnancy [cluster‐randomised trials].

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis [Multiple interventions]: Unintended pregnancy, Outcome 1 Unintended pregnancy ‐ cluster‐randomi sed trials .

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis [Multiple interventions]: Unintended pregnancy, Outcome 3 Unintended pregnancy ‐ cluster‐adjusted + individual .