The giant thermopower of an ionic liquid–based ionogel can be tuned within an ultrawide range by selective ion doping.

Abstract

Ionic thermoelectrics show great potential in thermal sensing owing to their ultrahigh thermopower, low cost, and ease in production. However, the lack of effective n-type ionic thermoelectric materials seriously hinders their applications. Here, we report giant and bidirectionally tunable thermopowers within an ultrawide range from −15 to +17 mV K−1 in solid ionic liquid–based ionogels. Particularly, a record high negative thermopower of −15 mV K−1 is achieved in the ternary ionogel, rendering it among the best n-type ionic thermoelectric materials under the same condition. A thermopower regulation strategy through ion doping to selectively induce ion aggregates to enhance ion-ion interactions is proposed. These selective ion interactions are found to be decisive in modulating the sign and magnitude of the thermopower in the ionogels. A prototype wearable device integrated with 12 p-n pairs is demonstrated with a total thermopower of 0.358 V K−1, showing promise for ultrasensitive thermal detection.

INTRODUCTION

Accurate detection of heat flux and temperature plays an essential role in numerous applications from industries to domestic usages. Thermoelectrics based on the Seebeck effect, in which a thermovoltage V is produced through charge diffusion under a temperature difference ∆T, provide a feasible and simple solution to converting heat to electricity directly, empowering them with the ability of thermal sensing (1). Common high-performance thermoelectric materials with either electrons or holes carrying both charges and heat have Seebeck coefficients (or thermopower, α = −V/∆T), ranging from only tens of to a few hundred microvolts per kelvin (2). The limited Seebeck coefficients of current thermoelectric materials greatly restrain their thermal sensing sensitivity, and in the thermopile configuration such as the thermoelectric heat flux sensor, a large number of elements should be necessarily integrated to magnify the signal output (3), which usually leads to complicated fabrication and high costs. Meanwhile, insulators with higher Seebeck coefficients have very low electrical conductivity, leading to large noises during measurement. It is challenging to notably improve the Seebeck coefficient without sacrificing other important thermoelectric properties such as electrical conductivity due to their strong intercoupling (4).

Over the past few years, giant thermopowers of the order of 10 mV K−1 have been reported frequently in ion conductors (5–13) or mixed ion-electron conductors (14–16). The greatly enhanced thermopowers compared with the best electronic thermoelectric materials and reasonable ionic conductivity allow more sensitive thermal sensing, especially for small temperature difference occasions such as the human body thermal monitoring. As an extra merit, considering conventional thermoelectric materials are rigid bulk metals or semiconductors, many ionic thermoelectric materials are flexible and easily fabricated. Zhao et al. (6) demonstrate the first ionic thermopile showing a thermal voltage of 0.333 V K−1 with only 18 pairs of legs, while 8000 legs of polysilicon (17) are required to match the output. The ionic thermoelectric materials are good candidates for scalable and wearable thermal sensors in health care applications, although the responsivity and stability are still to be optimized (18).

In the ionic thermoelectric materials, the electrical response to thermal stimuli is very similar to their electronic siblings; i.e., a thermovoltage will be built up when ions thermodiffuse from the hot side to the cold side under a temperature gradient (19) [also called Soret effect (20)]. Since the thermally driven ions can only accumulate at the electrodes instead of entering the external circuit, there is no constant current generated in the external circuit (21), but heat-to-electricity conversion can be achieved through an ionic thermoelectric supercapacitor design (6). The ionic thermopower αι is also derived from the ratio of the open circuit voltage over the temperature difference, i.e., αι = −V/∆T. In general, an ionic thermoelectric material is p-type with a positive thermopower if the cold electrode has a higher electrical potential, which indicates that the cations dominate the thermodiffusion, and vice versa. The ionic thermopower is correlated to the ion transport entropy in ionic thermodiffusion (22), which is determined by interactions between ions and the local environment. The ionic thermopower in aqueous and organic solutions have been intensively investigated in the last few years. Recently, solid electrolytes of giant ionic thermopower, especially polymer gels, attract great attention due to their advantages in manufacturing and device integration. The introduction of solid matrix can also significantly enhance the ionic thermopower through the ion-matrix interactions. The thermopower can be either positive or negative for different electrolytes within the same polymer matrix, depending on the dominating ion species in the thermodiffusion (8). Polymer ionogels based on nonvolatile ionic liquids (ILs) are less explored compared with hydrogels and preferred in many potential applications due to their great stability. A record high thermopower (+26 mV K−1) has been achieved in poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF-HFP)–based ionogels, which is attributed to the ion-dipole interaction between PVDF-HFP and the IL (10). It is recently reported that by changing the polymer composition, the ionic thermopower can be tuned from −4 to +14 mV K−1 in an IL-based polymer electrolyte (6). So far, almost all the strategies to tune the sign and magnitude of ionic thermopowers have been focused on modulating the interactions between ions and the matrix environment. However, owing to various considerations such as the stability and mechanical strength, suitable polymer matrices for electrolytes are limited, and the regulation of the interactions between the selected polymer matrix and ions is also challenging. Despite the significant advances in achieving giant ionic thermopowers, most state-of-the-art ionic thermoelectric materials are p-type or have positive ionic thermopowers. Up until now, n-type ionic thermoelectric materials are scarce, and the relatively low thermopower can hardly match the performance of p-type ionic thermoelectric materials. The lack of high-performance n-type materials seriously hampers the adoption of ionic thermopiles in practical applications.

Here, we propose a novel strategy in which strong ion-ion interactions are selectively introduced into the ionic thermoelectric materials to tune the ionic thermopower in desired positive or negative directions. We adopt a binary IL-based polymer ionogel as the start, which is flexible and can be manufactured using low-cost solution processes. When ionic salts that can closely interact with original ions are added to form ternary polymer ionogels, the ionic thermopower can be drastically tuned in either positive or negative directions within the range from −15 to +17 mV K−1 near room temperature and 60% relative humidity (RH). We achieve a giant negative thermopower of −15 mV K−1 using this strategy, reaching a record value for n-type ionic thermoelectric materials under the same condition. Through various characterization techniques including Raman, infrared, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopies, we conclude that the bidirectionally tunable thermopower results from interactions between ions of the salts and those of the IL. We also demonstrate a flexible wearable ionic thermoelectric device consisting of 12 p-n pairs based on the developed p- and n-type ionogels, achieving a device thermopower of 358 mV K−1.

RESULTS

Tunable ionic thermopower in ternary polymer ionogels

We chose a common binary IL-based polymer ionogel as a start for demonstration, which adopts the copolymer PVDF-HFP as a solid polymer matrix and the IL 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ([EMIM]) bis(trifluoro-methylsulfonyl)imide ([TFSI]) electrolyte. The pure EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel with a weight ratio of WIL:Wpolymer = 4:1 shows an ionic thermopower of around −4 mV K−1 at 60% RH, agreeing quite well with the result reported in literature (6).

Theoretically, for an equilibrium state of an ionic conductor under a temperature gradient, an electric field is established to balance the thermodiffusion and the concentration gradient-driven diffusion for mobile ion species, and then the thermopower can be given as (23)

| (1) |

where qi, ni, and Qi are the electric charge, concentration, and heat of transport of ion species i, respectively, and T is the temperature. The thermopower is directly related to the difference in heat of transport of cations and anions. The interactions on the ions coming from the polymer matrix and the surrounding ionic environment strongly influence the ionic heat of transport (6, 10, 11). Especially in a highly concentrated ionic environment like the IL, ion-ion interactions are prominent and contribute significantly to the heat of transport (24). It is therefore expected that adding specific salts into the binary ionogel can regulate the ionic environment and, in turn, selectively tune the ion interactions or heat of transport of ions in the system, consequently altering the sign and magnitude of the ionic thermopower. Along this way of selectively establishing strong ion-ion interactions with either anions or cations, we doped the binary polymer gel with lithium tetrafluoroborate (LiBF4) or 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride (EMIMCl), which preferentially interacts with the anions (TFSI−) or the cations (EMIM+) of the original IL, respectively, to tune the thermopower.

The preparation of ternary polymer ionogels with PVDF-HFP polymer matrix is similar to the process for the binary EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel, except that specific ionic salts are added to EMIMTFSI to form an IL solution before the mixing of the IL with PVDF-HFP solution. In the ternary polymer gels consisting of PVDF-HFP, ILs, and salts, the polymer is a host of the liquid electrolyte, and the IL acts as a liquid solvent for salts as well as an ion provider. At 60% RH, after doping 0.5 M LiBF4 in the EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel, the ionic thermopower of the polymer ionogel is boosted from −4 to −15 mV K−1 (fig. S3), which is much higher than the previous value (−4 mV K−1) for state-of-the-art n-type ionic thermoelectric materials and matches with the best performance of p-type ones (Fig. 1A). An n- to p-type conversion in the EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel with the ionic thermopower changing from −4 to +17 mV K−1 is attained by adding 0.5 M EMIMCl (fig. S3). The positive thermopower of +17 mV K−1 achieved with ionic salt doping is slightly higher than that (+14 mV K−1) obtained in EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel with nonionic poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) additive. The role of the added salts will be discussed in detail in later sections. Since the thermopower is also dependent on the RH as indicated in other IL-based ionogels (12), we measured the thermopower at 80% RH as well. The thermopowers of the 0.5 M LiBF4/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP and 0.5 M EMIMCl/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogels reach −18 and +23 mV K−1, respectively. The magnitudes of both ionogels slightly increase with higher RH, while the signs remain unaltered.

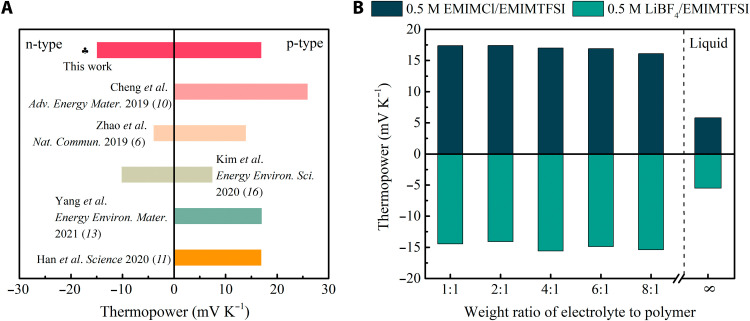

Fig. 1. Thermopower of the polymer gels.

(A) Thermopowers of ionic thermoelectric materials in the literature at 60% RH. (B) Thermopowers of the p- and n-type ionogels for different weight ratios of liquid electrolyte to polymer matrix PVDF-HFP. The salt concentration is maintained at 0.5 M.

Figure 1B shows the thermopower of the ternary ionogels doped with 0.5 M salts in IL electrolyte but with different electrolyte to polymer weight ratios at room temperature and 60% RH. When there is no PVDF-HFP matrix, the 0.5 M EMIMCl/EMIMTFSI and 0.5 M LiBF4/EMIMTFSI liquid electrolytes show thermopowers of +5.8 and −5.5 mV K−1, respectively. Incorporating the liquid electrolytes into the PVDF-HFP matrix retains the signs of the thermopower but greatly boosts their magnitudes with only ~10 weight % PVDF-HFP content. This implies that the PVDF-HFP in the ionogels not only acts as a matrix to constrain the liquid portion but also has a great impact on the ion thermodiffusion. Apparently, the ion-polymer chain interaction can greatly boost the thermopower, as also observed in the literature (6, 9–11). Note that when the liquid electrolytes form ionogels with PVDF-HFP, the thermopower is almost independent on the electrolyte/polymer weight ratio within the range considered. This indicates that small polymer fraction is sufficient to apply the influence on the ion thermodiffusion. The PVDF-HFP transforms from α phase to highly polar β phase with positively charged CH2 dipoles and negatively charged CF2 dipoles (25) when it forms gels with the IL (10, 26). The polymer can establish ion-dipole interactions with both cations (27) and anions (25, 28). It is conjectured that the PVDF-HFP matrix increases the heat of transport of both ions through ion-dipole interactions without obvious selectivity. Thus, the difference in heat of transport is magnified, and the dominating ions in the thermodiffusion still dominate; i.e., the thermopower is enlarged and the sign is retained. This could also explain why, in the cases of EMIMTFSI (6) and EMIMDCA (10), the thermopowers of neat IL (−0.85 and +6.9 mV K−1) both enhance to −4 and +26 mV K−1 in IL/PVDF-HFP ionogels, respectively. For comparison, we found positive thermopowers with both salts doping in poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) matrix (fig. S4). The ether oxygen in the polymer backbone is a strong electron donor to attract cations, whereas anions interact weakly (29, 30). Therefore, PEO promotes unilateral thermodiffusion.

Tuning negative thermopower by LiBF4 doping

LiBF4 shows good performance in enhancing the negative thermopower of the EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel. For the following measurements, the weight ratio of liquid electrolyte to polymer was controlled at 4:1. The salts were predissolved in the IL to attain various concentrations. Figure 2A and fig. S6A exhibit the thermopowers and ionic conductivities of LiBF4/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogels with different LiBF4 concentrations. The ionic conductivity of the ionogel gradually increases from 2 to around 4 mS cm−1 when the concentration of LiBF4 increases from 0 to 1 M. Upon the addition of LiBF4, the thermopower of the ionogel first increases from −4 to a maximum value of −15 mV K−1 when the concentration of LiBF4 increases to around 0.5 M and then slightly falls back to −11 mV K−1 at 1 M LiBF4. This drop might be due to the increase of viscosity of the liquid electrolyte at higher lithium salt concentration (31).

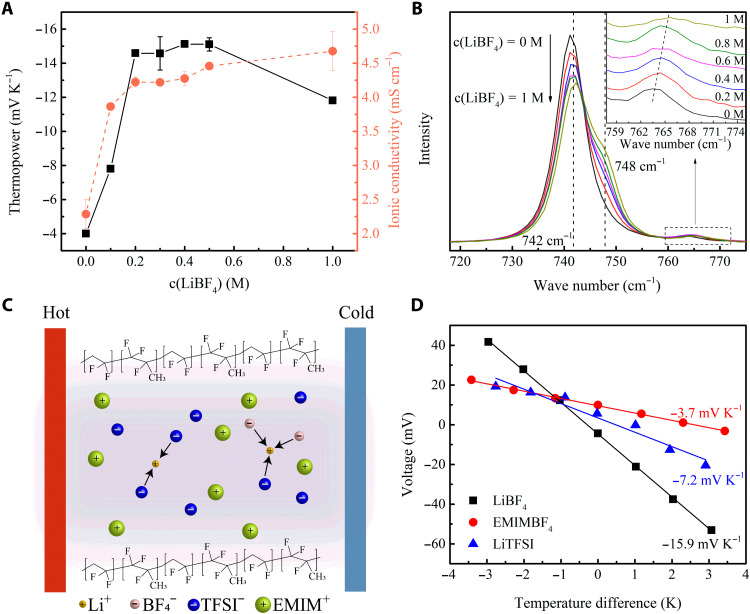

Fig. 2. Influence of LiBF4 concentration on the thermoelectric properties of the ionogels.

(A) Thermopower and ionic conductivity of the LiBF4/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel with varying LiBF4 concentration. (B) Raman spectra of LiBF4/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel for c(LiBF4) = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 M. All the spectra have been normalized with area between 717 and 775 cm−1. The enlarged region between 757 and 775 cm−1 is given in the inset for a better vision. (C) Schematic to illustrate the interaction between Li+ cations and anions during the thermodiffusion of ions in the polymer channel. (D) Thermopower of the EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogels with 0.5 M LiBF4, EMIMBF4, and LiTFSI, respectively.

The addition of lithium salts favors the thermodiffusion of the anions by establishing ion-ion interactions with the IL. The anions (TFSI− and BF4−) have strong coordination with the Li+ cations in an IL/lithium salt mixed electrolyte, as evidenced by experiments (32) and simulations (33), so Q− will be enlarged, resulting in a larger negative thermopower. The existence of lithium-anion clusters in the LiBF4/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogels is confirmed with Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 2B). The band at 742 cm−1 is assigned to free TFSI− anions for the pure IL ionogel, and as the concentration of LiBF4 increases, a new band grows at 748 cm−1, indicating that the TFSI− anions bond to the Li+ cations (32). Similarly, the band at 765 cm−1 is assigned to free BF4− anions (34), and this band becomes wider with higher LiBF4 concentration due to more coordinated BF4− anions locating at 770 cm−1. These results confirm that both TFSI− anions and BF4− anions form Li+-centered clusters in the mixed-anion LiBF4/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel. Owing to the large interactions that Li+ cations exerted on the anions, the heat of transport for the anions greatly enlarges, leading to enhanced negative thermopower with LiBF4 doping. A schematic diagram to demonstrate these ion-ion interactions during thermodiffusion is shown in Fig. 2C.

To further verify that the boost of the thermopower is due to ion-ion interactions between the anions and the Li+ cations, we conducted a control experiment, substituting the 0.5 M LiBF4 in the ionogel with 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate (EMIMBF4) of the same molar concentration so that the Li+ cations could be excluded, while BF4− anions were retained. The measured ionic thermopower of the resulting ionogel is −3.7 mV K−1 (Fig. 2D), almost equal to that of the pure EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel. This is because no strong interaction is introduced to significantly modulate the difference in the heat of transport for cations and anions. Besides, we found that the BF4− anions also contribute to stronger ion-ion interactions by using lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI), which has the same anion as the IL, as the dopant in the ionogel. The 0.5 M LiTFSI/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel shows a thermopower of −7.6 mV K−1. The BF4− anions exhibit larger polarity than TFSI− anions (35), leading to stronger and more compact coordination with Li+ cations, which contributes to even larger Q−. These two comparisons coherently confirm that the enhanced negative thermopower is derived from strong ion-ion interactions introduced by LiBF4 in the IL ionogel.

Reversed positive thermopower by adding EMIMCl

On the other hand, halide ions can change the sign of the thermopower of the IL ionogel. The thermopower and ionic conductivity of EMIMCl/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogels containing various concentrations of EMIMCl were also investigated. It can be seen in Fig. 3A that, with the addition of EMIMCl, the thermopower first changes from −4 mV K−1 to 0 and then further increases until it reaches a peak value as high as +17 mV K−1. The ionic conductivity increases with EMIMCl addition at the beginning and then remains almost unchanged as the concentration of EMIMCl further increases.

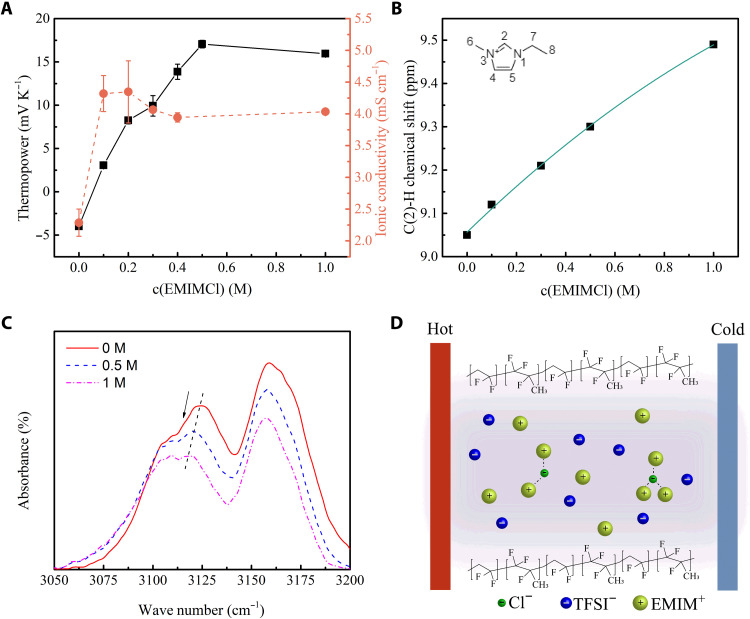

Fig. 3. Influence of EMIMCl concentration on the thermoelectric properties of the ionogels.

(A) Thermopower and ionic conductivity of the EMIMCl /EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel with varying EMIMCl concentrations. (B) Chemical shift of C(2)-H in the EMIMCl/EMIMTFSI mixture. (C) FTIR spectra of the EMIMCl/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel, c(EMIMCl) = 0, 0.5, and 1 M. (D) Schematic to illustrate the interaction between Cl− anions and cations during the thermodiffusion of ions in the polymer channel.

The EMIM+ cations form hydrogen bonds with the Cl− anions (36) so that Q+ will increase and the thermodiffusion will shift to a cation-dominant direction with a positive thermopower. The interactions between EMIMCl and the IL were studied by 1H NMR and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in the liquid state and ionogels, respectively. For 1H NMR measurements, different concentrations of EMIMCl/EMIMTFSI were dissolved in d6-acetone and measured. The entire 1H NMR spectra of the samples together with the peak assignment can be found in fig. S7, where the pure EMIMTFSI spectra are consistent with the literature results (37). Upon the increase in the concentration of EMIMCl, all peaks remain at their positions except for the peak assigned to the hydrogen in C(2)-H, the most acidic proton in the imidazolium ring (38), which gradually shifts from 9.05 to 9.49 parts per million, as shown in Fig. 3B. This peak shift indicates the formation of hydrogen bonds between C(2)-H in EMIM+ cations and Cl− anions, which is further confirmed by FTIR spectra (Fig. 3C). FTIR spectra of the IL-based ionogels from 3050 to 3200 cm−1 are shown, because this region contains characteristic features of the imidazolium ring. For the neat IL ionogel, the peak at 3126 cm−1 is assigned to the C(2)-H stretch (39). The red shift after adding EMIMCl is a good indicator of hydrogen bonds between the cation and Cl− anion (38). The 1H NMR and FTIR results can support and verify the hydrogen bonds that form between the EMIM+ cations and Cl− anions.

The formation of hydrogen bonds on the EMIM+ cations gives rise to larger Q+ and promotes the thermodiffusion of the cations, similar to what is observed with PEG treatment by Crispin’s group (6). Thus, the addition of Cl− anions can reverse the thermopower to a positive value. To further verify the essential effect of hydrogen bonds with the EMIM+ cations, we substitute the chloride with 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide (EMIMBr), in which Br− anions have comparative abilities on hydrogen bond formation and find similar thermopower (fig. S8). In summary, the anions dominate the thermodiffusion in the original IL/PVDF-HFP ionogel but with halide salts interacting with the cations, Q+ is increased, and the thermodiffusion of the cations is favored, thus tuning the thermopower toward a positive direction.

Flexible thermoelectric device

Owing to the large positive and negative ionic thermopowers in the ternary ionogels, we combined 12 pairs of the p-type 0.5 M EMIMCl/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP and n-type 0.5 M LiBF4/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogels to construct a flexible ionic thermoelectric device with a large total thermopower. As the polymer materials are soft and easy to bend, we can attach the device to the curved surface of human body to detect temperature change and heat flux or harvest body heat energy. Figure 4A shows the construction of the device by sandwiching a prepunched 1-mm-thick 3M VHB tape between copper electrodes patterned on polyethylene films. The p- and n-type ionogel solutions were alternately injected into the cavities in the 3M VHB tape, and the dried p- and n-type elements were connected in series by the electrodes. A temperature difference was generated along the cross-plane direction using two Peltier chips, and the corresponding thermovoltage between the two electrodes was recorded. The real-time temperature difference and voltage curves are shown in Fig. 4B. The open circuit voltage changes almost synchronously with the temperature difference, showing the fast response of the device with a relaxation time of about 50 s. Through a linear fitting of the thermovoltage with respect to the temperature difference, a total device thermopower of 0.3579 V K−1 is obtained (Fig. 4C). The average thermopower of one p-n pair is 29.8 mV K−1, very close to the sum of the thermopowers of a p-type (+17 mV K−1) and n-type (−15 mV K−1) leg pair.

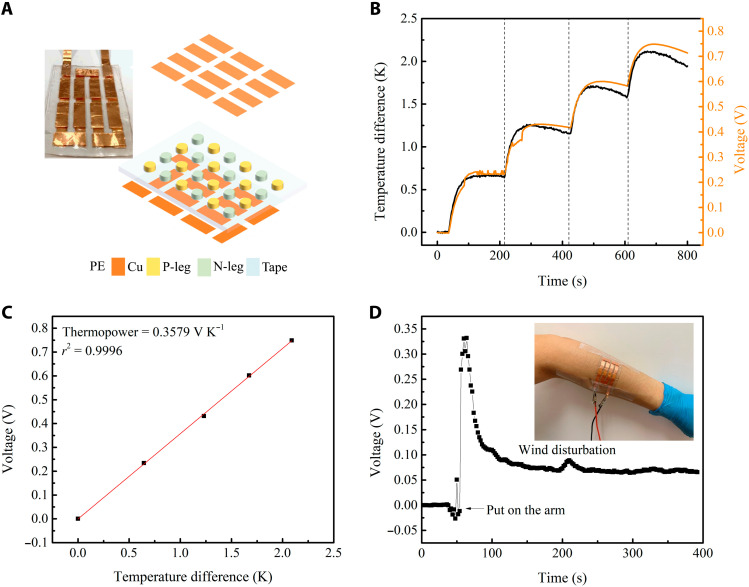

Fig. 4. Flexible thermoelectric device.

(A) A schematic of the design with 12 pairs of p- and n-type ionogels together with the picture of the device. (B) Voltage changes with temperature difference. (C) Linear fitting of voltage to temperature difference. (D) Voltage generated from the device when put on a human arm at 25°C. Photo credit: Sijing Liu, Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Figure 4D shows that the flexible device can be adhered to human arms and produce a stable thermovoltage in an indoor environment (25°C), which can be used to monitor the skin surface heat flux. When the device was worn on the arm, we observed a sharp voltage increase to 0.33 V in 10 s, since one side was heated immediately by the warm skin. The voltage then decayed as the temperature propagated from the skin to the top surface of the device until reaching a plateau at around 0.07 V. Even a small wind disturbation at 200 s was recorded by the voltage fluctuation. According to the measured total thermopower, the stable temperature difference across the device was around 0.2 K. The convective skin surface heat flux was then calculated to be 34.8 W m−2 based on the thermal conductivity of the ionogels (table S1). The temperature difference between the air and the skin was measured to be around 8 K, and the corresponding convective heat transfer coefficient can therefore be calculated based on the measured heat flux to be 4.35 W m−2 K−1, lying in the proper range for the heat transfer of human body in natural convection (40). A higher voltage signal can be expected if we conduct the measurement in a colder environment to enlarge the temperature difference. This wearable device can be used for high-sensitivity body heat flux monitoring in health care applications. For example, a typical 1-mm-thick commercial Hukseflux FHF02SC copper-constantan thermopile heat flux sensor offers a sensitivity of ~5 × 10−6 V/(W/m2) (41). In contrast, the sensitivity of this flexible wearable device of the same thickness can reach 1.8 × 10−3 V/(W/m2). Meanwhile, because of the high thermal resistivities of the polymer materials, a sufficient temperature gradient can be retained even if the sensor thickness is small.

This ionic thermoelectric effect can also be used to harvest heat by forming either a vertical (7, 14) or planar thermoelectric supercapacitor (10, 42). Although the thermally induced ion cannot pass through the electrodes, nor does it directly work on the external circuit, the generated thermovoltage can be harvested through the supercapacitor design as illustrated in fig. S9. The supercapacitor adopts an electrode-ionogel-electrode layered structure, and as the cross-plane temperature difference arouses thermovoltage in the electrolyte, connecting the two electrodes will allow electrons to flow through the external circuit to balance the thermovoltage. After heat and the external circuit are removed, the electrodes have been charged by trapped electrons and can discharge once connected again. The electrode properties play a major part in the discharge capacity, and carbon nanotube (CNT) electrodes with large specific surface areas can be used to deliver higher energy compared with metal electrodes (fig. S10A). The ionic thermoelectric capacitors fabricated in this work can generate an energy of 1006 μJ m−2 with Ag electrodes or 7982.5 μJ m−2 with CNT electrodes in half a thermal cycle (fig. S10B).

DISCUSSION

Different from previous efforts that focus on modulating the ionic thermopower in ionic conductors through engineering the ion-matrix interactions, here, we propose a tuning mechanism that takes advantage of strong ion-ion interactions in ternary polymer ionogels. We have demonstrated the effective modulation of the ionic thermopower of EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP polymer ionogel in both positive and negative directions simply with selective ion doping. With the addition of ion salts into the IL-based polymer ionogel to form ternary polymer electrolytes, the ionic thermopower can be continuously tuned from −15 to +17 mV K−1, which is the widest tuning range reported so far under the same condition. Particularly, a giant negative thermopower of −15 mV K−1 is achieved in 0.5 M LiBF4/EMIMTFSI/PVDF-HFP ionogel, among the highest values of the reported n-type ionic thermoelectric materials. We show that, through the appropriate selection of doping salts, which interact preferentially with the cations or the anions, the thermodiffusion of the ions in ionogels can be effectively controlled in a desired manner to tailor the ionic thermopower. It is expected that this ion regulation strategy can be applied in other ionic thermoelectric materials. A prototype flexible ionic thermoelectric wearable device, consisting of 12 pairs of the p- and n-type polymer ionogel elements, shows a thermopower of 0.3579 V K−1. It can sensitively measure the skin heat flux by producing a thermovoltage using the heat of the human body. These results provide a promising solution to reach the demands of future human interactive technology from the aspect of heat flux monitoring or power supplies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

PVDF-HFP [number-average molecular weight (Mn) = 130,000], poly(methyl methacrylate) [weight-average molecular weight (Mw) = 350,000 and 15,000], LiBF4 (98%), and lithium LiTFSI were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. EMIMTFSI, EMIMBF4, EMIMCl, EMIMBr, PEO powder (Mv = 100,000 and 600,000), and PVDF (Mw = 1000,000) were from Aladdin Industrial Corporation. Multiwalled CNTs are provided by XFNANO. All chemicals were used as received.

Preparation of the polymer gels

The polymer gels were synthesized with a simple solution process. First, the salts were dissolved in ILs with the desired molar concentration in a glove box. Meanwhile, PVDF-HFP was dissolved in acetone, with a concentration of 0.1 g ml−1. The polymer solution was stirred at 50°C until PVDF-HFP was completely dissolved in the acetone and the solution became transparent and homogeneous. Then, the premixed liquid electrolyte was added to the PVDF-HFP solution. It was stirred for half an hour before use. The solution was then drop-casted onto a glass slide and dried in an oven at 60°C for 10 min to form a freestanding polymer gel film.

Thermopower measurement

The thermopower measurement was conducted on a homemade setup in the in-plane direction (fig. S1). Two Peltier devices were used to create hot and cold terminals. Two T-type thermocouples were placed on the copper electrodes near the polymer gel. The thermocouple tips were pasted with thermal grease to ensure accurate measurements of the temperature difference. The Keithley 2182A voltage meter and National Instruments 9213 thermocouples data logger were connected to a computer to record the thermovoltage and temperature every 2 s. The thermovoltage usually reached a plateau in 2 min. The measurements were conducted at room temperature (~25°C) and ~60% RH unless specified. We also deposited a 50-nm Au protection layer on the copper electrodes, and the measured thermopowers were just the same (fig. S2).

Material characterizations

Ionic conductivity for the polymer gels was measured with a stainless steel blocking electrodes mold using a Metrohm Autolab PGSTAT302N electrochemical workstation for impedance analysis over the frequency range from 0.1 Hz to 1 MHz by applying 10 mV perturbation. The Raman spectroscopy measurements of the polymer gels were performed using a Renishaw inVia Micro Raman system with 633-nm laser and a Leica objective with ×50 magnification. The spectra were fitted by PeakFit v4.12 software. NMR spectra were measured with a Bruker AVII 400 NMR spectrometer at a frequency of 400 MHz using d6-acetone as the solvent. The FTIR spectra were measured using a Bruker Vertex 70 Hyperion 1000 spectrometer equipped with the ATR (attenuated total reflection) accessory. The thermal conductivity was measured with hot disk methods.

Fabrication of flexible thermoelectric device

Conductive copper tapes were patterned on a thin polyethylene substrate as the bottom electrodes. A 1-mm-thick 3M VHB tape was punched with 4 mm × 4 mm square pore arrays and then adhered to the bottom electrode layer. Next, copper tapes as the top electrodes were attached to the top of the VHB tape. The p- and n-type ternary polymer solutions with 0.5 M lithium salts or chlorides were injected into the pores using a needle and then dried at 60°C in an oven. Thereafter, another thin polyethylene film was covered on top. For the thermopower measurement, T-type thermocouples were attached beneath the inner sides of the polyethylene films. During the test, the device was sandwiched between two Peltier chips to generate temperature difference.

The demonstration was performed in compliance with a protocol that was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (OKT20EG06). The heat flux sensor was attached on a volunteer’s arm. The informed written consent of the participant has been obtained.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The authors are thankful for the financial support from the Hong Kong General Research Fund (grant no. 16206020) and the Center on Smart Sensors and Environmental Technologies (grant no. IOPCF21EG01) in the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. This work was also supported in part by the Project of Hetao Shenzhen-Hong Kong Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation Zone (HZQB-KCZYB-2020083).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: S.L., Y.Y., and B.H. Methodology: S.L. and Y.Y. Investigation: S.L., Y.Y., H.H., J.Z., G.L., and T.H.T. Supervision: B.H. Writing—original draft: S.L. and Y.Y. Writing—review and editing: S.L., Y.Y., and B.H.

Competing interests: B.H., Y.Y., and S.L. are inventors on a patent application related to this work filed by the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (no. US 63/181971, filed: 30 April 2021). The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S11

Table S1

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Van Herwaarden A. W., Sarro P. M., Thermal sensors based on the Seebeck effect. Sens. Actuators 10, 321–346 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood C., Materials for thermoelectric energy conversion. Rep. Prog. Phys. 51, 459–539 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graf A., Arndt M., Sauer M., Gerlach G., Review of micromachined thermopiles for infrared detection. Meas. Sci. Technol. 18, R59–R75 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snyder G. J., Toberer E. S., Complex thermoelectric materials. Nat. Mater. 7, 106–114 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonetti M., Nakamae S., Roger M., Guenoun P., Huge Seebeck coefficients in nonaqueous electrolytes. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 114513 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao D., Martinelli A., Willfahrt A., Fischer T., Bernin D., Khan Z. U., Shahi M., Brill J., Jonsson M. P., Fabiano S., Crispin X., Polymer gels with tunable ionic Seebeck coefficient for ultra-sensitive printed thermopiles. Nat. Commun. 10, 1093 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao D., Wang H., Khan Z. U., Chen J. C., Gabrielsson R., Jonsson M. P., Berggren M., Crispin X., Ionic thermoelectric supercapacitors. Energ. Environ. Sci. 9, 1450–1457 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim S. L., Hsu J. H., Yu C., Thermoelectric effects in solid-state polyelectrolytes. Org. Electron. 54, 231–236 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li T., Zhang X., Lacey S. D., Mi R., Zhao X., Jiang F., Song J., Liu Z., Chen G., Dai J., Yao Y., Das S., Yang R., Briber R. M., Hu L., Cellulose ionic conductors with high differential thermal voltage for low-grade heat harvesting. Nat. Mater. 18, 608–613 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng H., He X., Fan Z., Ouyang J., Flexible quasi-solid state ionogels with remarkable Seebeck coefficient and high thermoelectric properties. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1901085 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han C. G., Qian X., Li Q., Deng B., Zhu Y., Han Z., Zhang W., Wang W., Feng S. P., Chen G., Liu W., Giant thermopower of ionic gelatin near room temperature. Science 368, 1091–1098 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang Y., Cheng H., He H., Wang S., Li J., Yue S., Zhang L., Du Z., Ouyang J., Stretchable and transparent ionogels with high thermoelectric properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2004699 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X., Tian Y., Wu B., Jia W., Hou C., Zhang Q., Li Y., Wang H., High-performance ionic thermoelectric supercapacitor for integrated energy conversion-storage. Energy Environ. Mater. 2021, 1–8 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S. L., Lin H. T., Yu C., Thermally chargeable solid-state supercapacitor. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1600546 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim B., Na J., Lim H., Kim Y., Kim J., Kim E., Robust high thermoelectric harvesting under a self-humidifying bilayer of metal organic framework and hydrogel layer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1807549 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim B., Hwang J. U., Kim E., Chloride transport in conductive polymer films for an n-type thermoelectric platform. Energ. Environ. Sci. 13, 859–867 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez-Marín A. P., Lopeandía A. F., Abad L., Ferrando-Villaba P., Garcia G., Lopez A. M., Muñoz-Pascual F. X., Rodríguez-Viejo J., Micropower thermoelectric generator from thin Si membranes. Nano Energy 4, 73–80 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stout R. F., Khair A. S., Diffuse charge dynamics in ionic thermoelectrochemical systems. Phys. Rev. E 96, 022604 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Würger A., Thermal non-equilibrium transport in colloids. Rep. Prog. Phys. 73, 126601 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eastman E. D., Theory of the Soret effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 50, 283–291 (1928). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H., Zhao D., Khan Z. U., Puzinas S., Jonsson M. P., Berggren M., Crispin X., Ionic thermoelectric figure of merit for charging of supercapacitors. Adv. Electron. Mater. 3, 1700013 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agar J. N., Mou C. Y., Lin J. L., Single-ion heat of transport in electrolyte solutions. A hydrodynamic theory. J. Phys. Chem. 93, 2079–2082 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Würger A., Thermopower of ionic conductors and ionic capacitors. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 042030 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao D., Würger A., Crispin X., Ionic thermoelectric materials and devices. J. Energy Chem. 61, 88–103 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramasundaram S., Yoon S., Kim K. J., Park C., Preferential formation of electroactive crystalline phases in poly(vinylidene fluoride)/organically modified silicate nanocomposites. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 46, 2173–2187 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serra J. P., Pinto R. S., Barbosa J. C., Correia D. M., Gonçalves R., Silva M. M., Lanceros-Mendez S., Costa C. M., Ionic liquid based fluoropolymer solid electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 25, e00176 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shamsuri A. A., Daik R., Jamil S. N. A. M., A succinct review on the pvdf/imidazolium-based ionic liquid blends and composites: Preparations, properties, and applications. Processes 9, 761 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li L., Wang M., Wang J., Ye F., Wang S., Xu Y., Liu J., Xu G., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Yan C., Medhekar N. V., Liu M., Zhang Y., Asymmetric gel polymer electrolyte with high lithium ion conductivity for dendrite-free lithium metal batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 8033–8040 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar Y., Hashmi S. A., Pandey G. P., Lithium ion transport and ion-polymer interaction in PEO based polymer electrolyte plasticized with ionic liquid. Solid State Ion. 201, 73–80 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaurasia S. K., Singh R. K., Chandra S., Ion-polymer and ion-ion interaction in PEO-based polymer electrolytes having complexing salt LiClO4 and/or ionic liquid, [BMIM][PF6]. J. Raman Spectrosc. 42, 2168–2172 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamada Y., Wang J., Ko S., Watanabe E., Yamada A., Advances and issues in developing salt-concentrated battery electrolytes. Nat. Energy 4, 269–280 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lassègues J.-C., Grondin J., Talaga D., Lithium solvation in bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide-based ionic liquids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8, 5629–5632 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haskins J. B., Bauschlicher C. W., Lawson J. W., Ab initio simulations and electronic structure of lithium-doped ionic liquids: Structure, transport, and electrochemical stability. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 14705–14719 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsyuba S. A., Dyson P. J., Vandyukova E. E., Chernova A. V., Vidiš A., Molecular structure, vibrational spectra, and hydrogen bonding of the ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methyl-1H-imidazolium tetrafluoroborate. Helv. Chim. Acta 87, 2556–2565 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong J., Xiao X., Liang X., Von Solms N., Huo F., He H., Zhang S., Insights into the solvation and dynamic behaviors of a lithium salt in organic- and ionic liquid-based electrolytes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 19216–19225 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong K., Zhang S., Wang D., Yao X., Hydrogen bonds in imidazolium ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 9775–9782 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Agostino C., Mantle M. D., Mullan C. L., Hardacre C., Gladden L. F., Diffusion, ion pairing and aggregation in 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium-based ionic liquids studied by 1H and 19F PFG NMR: Effect of temperature, anion and glucose dissolution. ChemPhysChem 19, 1081–1088 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cha S., Kim D., Anion exchange in ionic liquid mixtures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 29786–29792 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiefer J., Fries J., Leipertz A., Experimental vibrational study of imidazolium-based ionic liquids: Raman and infrared spectra of 1-ethyl-3methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ethylsulfate. Appl. Spectrosc. 61, 1306–1311 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurazumi Y., Tsuchikawa T., Ishii J., Fukagawa K., Yamato Y., Matsubara N., Radiative and convective heat transfer coefficients of the human body in natural convection. Build. Environ. 43, 2142–2153 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hukseflux, “User manual FHF02SC”; www.hukseflux.com/uploads/product-documents/FHF02SC_manual_v1803.pdf.

- 42.Akbar Z. A., Jeon J. W., Jang S. Y., Intrinsically self-healable, stretchable thermoelectric materials with a large ionic Seebeck effect. Energ. Environ. Sci. 13, 2915–2923 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arduengo A. J. III, Dixon D. A., Harlow R. L., Dias H. V. R., Booster W. T., Koetzle T. F., Electron distribution in a stable carbene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 6812–6822 (1994). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S11

Table S1

References