Abstract

Objectives:

Sickle cell disease related pulmonary hypertension (SCD-PH) is a complex disorder with multifactorial contributory mechanisms. Previous trials have evaluated the efficacy of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) therapies in SCD-PH with mixed results. We hypothesized that a subset of patients with right heart catheterization (RHC) confirmed disease may benefit from PAH therapy.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients with SCD-PH diagnosed by RHC who were treated with phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor (PDE5-I) therapy for ≥4 months between 2008–2019 at two institutions.

Results:

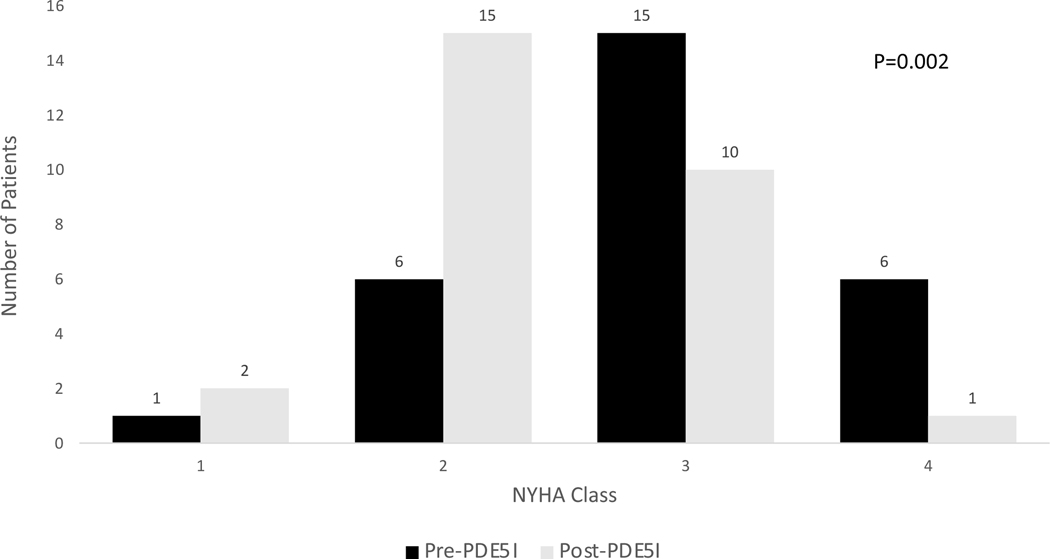

Thirty-six patients were included in the analysis. The median age (IQR) upon PDE5-I initiation was 47.5 years (35 to 51.5 years); 58% were female and twenty-nine (81%) had HbSS disease. Of these, 53% of patients had a history of acute chest syndrome, 42% had a history of venous thromboembolism and 38% had imaging consistent with chronic thromboembolic PH. Patients were treated for a median duration of 25 months (IQR 13–60 months). Use of PDE5-I was associated with a significant improvement in symptoms as assessed by NYHA Class (p=0.002).

Conclusions:

In SCD patients with PH defined by RHC, PDE5-I therapy was tolerated long-term and may improve physical activity.

Keywords: Sickle Cell Disease, Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitor

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common genetic disorder worldwide, affecting an estimated 100,000 people in the United States and millions throughout the world1–2. Chronic hemolysis and recurrent vaso-occlusion, the two key hallmarks of the disease, result in progressive vasculopathy that underlies much of the accumulative end-organ dysfunction, leading to increasing morbidity and accelerated mortality. This systemic vasculopathy affects multiple organs; in the lungs, the vascular endothelial dysfunction leads to intimal and smooth muscle proliferation which results in the development of pulmonary hypertension (PH)3. Other mechanisms contributing toward PH in this population include elevated pulmonary vascular blood flow, secondary to the anemia related increase in cardiac output, chronic pulmonary thromboembolic disease, in situ thromboses and intravascular hemolysis leading to pulmonary vasoconstriction as a consequence of reactive oxygen species formation and reduced nitric oxide bioavailability4–5. Hemodynamic studies reveal that 6.2–10.4% of adults living with SCD develop PH6–7. Patients with SCD- related PH have reduced functional capacity and an estimated 5-year survival of 63%.8–9 Hemodynamically, SCD-related PH is a complex disorder; 40% have pre-capillary PH, and 60% have features of post-capillary PH related to left-sided heart disease10. Additionally, ten to fifteen percent of those with post-capillary PH have hemodynamic features of pre-capillary PH suggestive of combined pre- and post-capillary PH11. Investigators and clinicians have been interested in the potential use of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) medications to treat SCD-related pre-capillary PH12. However, three randomized clinical trials of vasodilator therapy have been conducted in this population and none of them were successful. Two randomized placebo-controlled trials evaluated the endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan in SCD patients with RHC-defined pre-capillary (ASSET-1) or post-capillary PH (ASSET-2)13. Both trials were prematurely terminated due to insufficient enrollment of patients. A third trial compared the safety and efficacy of sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE5-I), with placebo in SCD patients (Walk-PHaSST)14 with an increased tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV), suggestive of PH risk, by echocardiography. The study was terminated prior to completion of enrollment due to an increase in serious adverse events in the sildenafil group, primarily due to hospitalization for vaso-occlusive events (VOEs)14.

Since the termination of Walk-PHaSST, concern has remained that use of sildenafil (and other PDE5-Is) in SCD-related PH may be associated with an increased risk of VOE and potentially other worse clinical outcomes10. More recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) re-classified SCD-related PH under WHO Group 515, underscoring that there are heterogeneous etiologies associated with it. As a result of these factors, the prospective clinical investigation of vasodilators approved for pre-capillary PH (similar to WHO Group 1 PAH) in SCD have largely halted. Despite this classification re-assignment, many PH centers treating patients with SCD continue to use PAH medications off-label in those with RHC-defined pre-capillary PH, given the limited therapeutic options available16. In our clinical experience, some patients have tolerated PDE5-I long-term despite warnings against use of this class of medications. This raises the question of safety and tolerability in a subset of patients with SCD-PH. We hypothesized that patients with right heart catheterization (RHC) confirmed pre-capillary PH, and a SCD phenotype which was more hemolytic and less vasoocclusive, may comprise this patient group17. To address these clinically important questions, we collected the data from two centers with expertise in SCD-PH to evaluate the long-term experience with PDE5-I in this population.

Methods

Study Design

This study is a retrospective medical record review performed at two tertiary care referral centers for sickle cell disease, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD and Boston University/Boston Medical Center (BMC). The study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards at both institutions.

Study Population

We used a study-specific, standardized case report form to uniformly extract data from the electronic medical record systems with scanned paper medical charts reviewed as needed to complete data collection. Inclusion criteria for the study population were: 1) a diagnosis of SCD; 2) a RHC-defined diagnosis of PH as defined by a pulmonary artery mean pressure (mPAP) of ≥25 mm Hg (based on the definition prior to 2019); 3) prescribed and/ or reported use of PDE5-I therapy for a duration of >16 weeks.

The electronic medical record of all SCD patients treated at each institution was searched for any patients 18 years and older with mention of sildenafil or tadalafil. Data was collected from records dated from 2008–2018. Baseline data (prior to PDE5-I initiation) including demographics, RHC hemodynamic measurements, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), 6-minute walk test distance (6MWD), vital signs, laboratory values, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class and imaging assessing for the presence of chronic thromboembolic disease were collected. Duration of PDE5-I use was reported in months. Follow-up documentation of the same parameters and occurrence and date of death were recorded where available. Patients who participated in the Walk-PHaSST study were included if they continued on sildenafil therapy after the 16-week clinical trial period.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented using median (interquartile ratio IQR) and categorical variables by number and percentage. Differences in the pre- and post-PDE5-I datasets were tested using the non-parametric Wilcoxon Sign rank test (for continuous variables) and McNemar test (for categorical variables). The statistical analyses were performed using Stata 16.0 and a P value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the analyses.

Results

Study Population and Patient Characteristics

The initial search yielded 94 patients at the NIH and one at BMC (n=95); those without baseline RHC data or receiving PDE5-I therapy for less than 16 weeks were excluded (n=55). All patients who were excluded were from the NIH, reflective of their participation as a clinical trial site in Walk-PHaSST. One patient who commenced PDE5-I after bone marrow transplantation for treatment of SCD was excluded. One patient was excluded because their data was entirely from the Walk-PHaSST clinical trial. Two patients were excluded for having baseline RHC with mPAP less than 25 mm Hg. Thirty-six patients were included in the current analysis (35 patients from the NIH, one patient from BMC). Eight of the 36 (22%) had participated in the Walk-PHaSST clinical trial but continued treatment after the trial completed.

The median age (IQR) of patients upon PDE5-I initiation was 47.5 years (35 to 51.5 years); 58% were female and twenty-nine (81%) had HbSS disease (Table 1). More than half of patients had a history of acute chest syndrome (53%), systemic hypertension (56%), or chronic kidney disease (56%). Sixteen (44%) had a history of leg ulcers and sixteen (42%) had a history of venous thromboembolism (deep venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism). Twenty-two (61%) were receiving hydroxyurea, fourteen (42%) were on chronic transfusion therapy and sixteen (43%) used long-term oxygen therapy. Some patients were on PAH therapy prior to initiation of PDE5-I therapy; intravenous epoprostenol was used in three patients, oral riociguat in two and oral bosentan in six. Of the 34 patients who underwent ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scanning to evaluate for chronic thromboembolic disease, 13 (38.2%) had findings consistent with high or intermediate probability of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

Table 1:

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | No. of Patients Evaluated | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin genotype - no. (%) | 36 | |

| Hb-SS | 29 (80.5) | |

| Hb-SC | 5 (13.9) | |

| other † | 2 (5.6) | |

| Age - yr. median (IQR) | 36 | 47.5 (35.0 – 51.5) |

| Female sex - no. (%) | 36 | 21 (58.3) |

| Transthoracic echocardiography | ||

| RV Dilation – no. (%) | 29 | 13 (44.8) |

| Impaired RV systolic function – no. (%) | 28 | 22 (78.6) |

| Tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (m/sec) – median (IQR) | 29 | 3.4 (3.0 – 3.8) |

| Right heart catheterization | ||

| PAWP – mmHg (SD) | 36 | 15 (12 – 18) |

| CO - L/min (SD) | 33 | 7.6 (6.6 – 9.9) |

| RA (mmHg) – median (IQR) | 34 | 10 (8 – 13) |

| Mean PAP (mmHg) – median (IQR) | 36 | 34 (29.3 – 43) |

| TPG – mmHg (SD) | 35 | 22 (12 – 29) |

| PVR - dynes/sec/cm3 (SD) | 34 | 227 (107 – 346) |

| Ambulatory Oxygen saturation minimum – median (IQR) | 22 | 93 (87 – 97) |

| Six-minute walk distance (m) – median (IQR) | 25 | 407.5 (279 – 454) |

| New York Heart Association class - no. (%) | 28 | |

| I no. (%) | 1 (3.6) | |

| II no. (%) | 6 (21.4) | |

| III no. (%) | 15 (53.6) | |

| IV no. (%) | 6 (21.4) | |

| History of stroke n (%) | 36 | 6 (16.7) |

| History of Acute Chest Syndrome n (%) | 36 | 19 (52.8) |

| History of venous thromboembolism n (%) | 36 | 16 (44.4) |

| History of leg ulcers n (%) | 36 | 16 (44.4) |

| History of hypertension - n (%) | 36 | 20 (55.8) |

| History of chronic kidney disease - n (%) | 36 | 20 (55.8) |

| History of Asthma - n (%) | 36 | 11 (30.6) |

| History of liver disease related to iron overload - n (%) | 36 | 17 (47.2) |

| History of Tobacco Use - n (%) | 36 | 12 (33.3) |

| Hydroxyurea therapy - n (%) | 36 | 22 (61.1) |

| Home oxygen therapy -n (%) | 35 | 16 (43.2) |

| Chronic Transfusion Therapy - n (%) | 35 | 14 (40.0) |

includes one patient HbS-β+, one patient HbS-β0

Hb= hemoglobin; RV= right ventricle RA= right atrium, PAP= pulmonary artery pressure, CO= cardiac output, PAWP pulmonary artery wedge pressure, TPG= transpulmonary gradient, PVR= pulmonary vascular resistance.

PAH =pulmonary arterial hypertension;

Baseline Clinical, Laboratory and Hemodynamic Data

As expected, this cohort reported exercise limitations; 16.7% were NYHA Class II, 41.7% were NYHA Class III and 16.7% were NYHA Class IV at the time of PH diagnosis (Table 1). Subjects had a median (IQR) hemoglobin concentration of 8.5 (7.7 to 9.5) g/dl, and a lactate dehydrogenase of 408 (384 to 601) U/L, reflective of a chronic hemolytic anemia. The brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (226 [83 to 501] pg/mL and N-terminal-pro BNP (706 [270 to 1681]) pg/ml levels were elevated, reflective of right ventricular strain. There was reduced exercise capacity reflected by a reduced 6MWD of 407.5 (279 to 454) meters. By TTE, all patients had an elevated tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity with a median (IQR) of 3.4 (3.0 to 3.8) m/sec and impaired right ventricular systolic function was observed in 78.6% of subjects. RHC demonstrated mild to moderate PH with a median (IQR) mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) of 34 (29 to 43) mmHg, pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP) of 15 (13 to 18) mmHg and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of 209.6 (107.7 to 365.6) dynes.sec/cm5. Using a transpulmonary pressure gradient (TPG) of > 12 mmHg, 30/36 patients had pre-capillary PH with the remaining 6 patients displaying post-capillary PH physiology with an elevated PAWP.

Long-term Cardiopulmonary Effects of PH in SCD with PDE5 Inhibition

Thirty-five (97.2%) patients were treated with sildenafil (one patient received tadalafil) for a median time period of 25 months (IQR 13–60 months) (Table 3). Six patients remained on PDE5-I therapy at the time of data collection. A dose of 25mg three times a day was the most frequent treatment regimen (N=20). The most frequent final dose at the time of data collection was 100mg three times a day (N=10). Twenty-two of the 36 patients (61.1%) were deceased at the time of data collection, reflective of the increased mortality of SCD-PH6–7, 9–10. Unfortunately, the cause of death was not recorded in those who died. The most common adverse event observed on PDE5-I were ophthalmologic related complaints in 3 patients (11.5%). Only 1 patient discontinued medication because of VOE (Table 3).

Table 3:

Long-term Tolerability of PDE5-Inhibitors

| No. of Patients Evaluated | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Months documented on PDE5 Inhibitor – median (IQR) | 36 | 25 (13 – 55.5) |

| Listed Reason for Discontinuation – no. (%) | 36 | |

| Discontinued Following WalkPHaSST Recommendations | 5 (13.2) | |

| Continued on Therapy | 6 (15.8) | |

| Ophthalmologic Problems | 3 (7.9) | |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 1 (2.6) | |

| Diarrhea | 1 (2.6) | |

| Hypotension | 1 (2.6) | |

| Vaso-occlusive Events | 1 (2.6) | |

| Other (insurance issues, noncompliance) | 3 (7.9) |

PDE5 = phosphodiesterase-5

Long-term treatment of PH in SCD patients with PDE5-I was associated with a significant improvement in symptoms as assessed by NYHA Class (p=0.002) (Figure 1). However, there was no change in 6MWD (371.0 ±26.8 meters [pre] vs 387.7 ±26.1 meters [post] p=0.413), TRV 3.40 ± 0.48 m/s [pre] vs. 3.31 ± 0.61 m/s [post] p=0.417) or cardiopulmonary hemodynamics with PDE5-I therapy.

Figure 1: Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor therapy on New York Heart Association Class.

Patients with pulmonary hypertension of sickle cell disease displayed improved symptoms as assessed by New York Heart Association Class with PDE5-I therapy. Prior to therapy, most patients were NYHA Class 3 or 4 (n=21). With therapy, the highest number of patients were NYHA Class 2 (n=15) and there was an overall shift towards improved symptoms (p=0.002).

PDE5-I=phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, NYHA=New York Heart Association

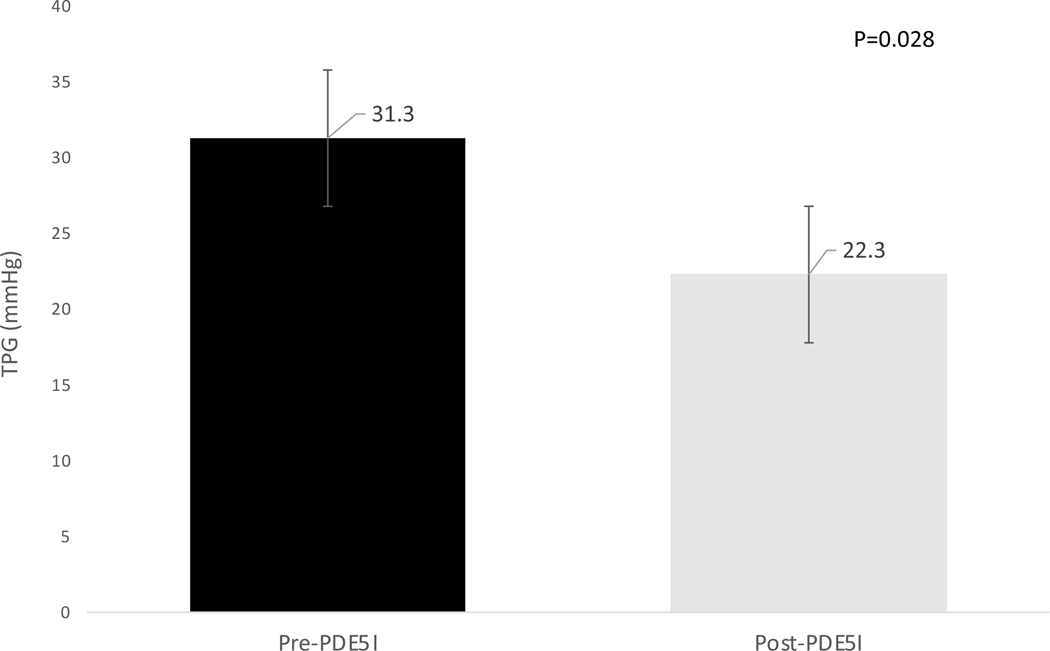

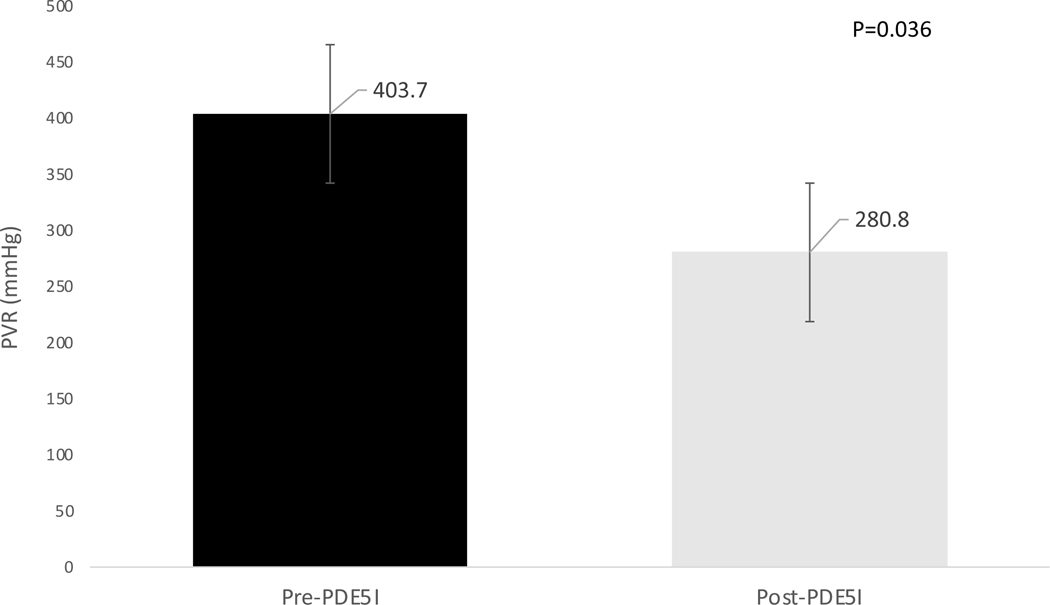

Two subgroup analyses were performed. In the first, 15 patients (41.7%) were included with a baseline PVR greater than or equal to 240 dynes/sec/cm3 (3 Wood units). In this cohort of patients, there was a significant improvement in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) [pre-PDE5-I 385.6 dynes/sec/cm3 (330.5 to 494.5) to post-PDE5-I 261 dynes/sec/cm3 (189.5 to 350) (p=0.04)] and TPG [29 mmHg (28 to 31) pre-PDE5-I to 22 mmHg (18 to 23) post PDE5-I (p=0.03)] (Figures 2 and 3). There were no significant changes in functional outcomes, including NYHA class or 6MWD in this cohort, or in other hemodynamic parameters (Table 4). The second subgroup analysis examined the sixteen patients (44.4%) treated with PDE5-I for at least 36 months. In this group, the NYHA class was also significantly improved following PDE5-I therapy (p=0.05), however no change in 6MWD or hemodynamic parameters occurred (Table 5).

Figure 2: Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor therapy on transpulmonary gradient in patients with a baseline PVR ≥ 240 dynes.sec/cm5.

In the subgroup of patients with baseline pre-capillary PH as defined by a PVR ≥ 240 dynes.sec/cm5 (n=15), long-term PDE5-I therapy resulted in a decreased TPG consistent with improved pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension (p=0.028).

TPG=transpulmonary gradient (mmHg), PVR=pulmonary vascular resistance, PDE5I=phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

Figure 3: Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor therapy on pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in patients with a baseline PVR ≥ 240 dynes.sec/cm5.

In the subgroup of patients with baseline pre-capillary PH as defined by a PVR ≥ 240 dynes.sec/cm5 (n=15), long-term PDE5-I therapy resulted in a decreased PVR consistent with improved pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension (p=0.036).

PVR=pulmonary vascular resistance, PDE5I=phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors.

Table 4:

Hemodynamics in Subjects with Baseline Elevated PVR

| Pre-PDE5I | Post-PDE5I | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NYHA Class – median (IQR) | 3 (2, 3) | 2 (2,3) | 0.289 |

| 6MWD (m) – median (IQR) | 420 (292, 454) | 376 (295, 480) | 0.612 |

| Right heart catheterization | |||

| RA (mmHg) – median (IQR) | 10.5 (6.5, 13.5) | 9.5 (7, 11.5) | 0.726 |

| PAP (mmHg) – median (IQR) | 44 (37.5, 46) | 37 (32, 43) | 0.141 |

| CO (L/min) – median (IQR | 6.1 (5.4, 6.9) | 7 (5.5, 8.2) | 0.069 |

| PAWP (mmHg) – median (IQR) | 13 (10, 16) | 12.5 (11.5, 18.5) | 0.205 |

| TPG (mmHg) – median (IQR) | 29 (28, 31) | 22 (18, 23) | 0.028 * |

| PVR (dynes/sec/cm3) - median (IQR) | 385.6 (330.5, 494.5) | 261 (189.5, 350) | 0.036 * |

RA= right atrium, PAP= pulmonary artery pressure, CO= cardiac output, PAWP pulmonary artery wedge pressure, TPG= transpulmonary gradient, PVR= pulmonary vascular resistance,

Table 5:

Functional Outcomes in Subjects treated with PDE5-I for > 36 months

| Characteristic | Pre-PDE5I | Post-PDE5I | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| NYHA Class - median (IQR) | 3 (2, 3) | 2 (2,2) | 0.051* |

| 6MWD (m) - median (IQR) | 414 (279, 454) | 390.5 (330, 480) | 0.345 |

| Right heart catheterization | |||

| RA (mmHg) – median (IQR) | 8 (7, 12) | 11 (6, 12) | 0.824 |

| PAP (mmHg) - median (IQR) | 34 (29, 43) | 37 (35, 40) | 0.421 |

| CO (L/min) – median (IQR | 7.3 (5.4, 10.1) | 6.2 (5.6, 9) | 0.314 |

| PAWP (mmHg) - median (IQR) | 13 (11, 15) | 14 (12, 20) | 0.477 |

| TPG (mmHg) – median (IQR) | 22.5 (13, 28) | 19.5 (17, 24) | 1.000 |

| PVR (dynes/sec/cm3) - median (IQR) | 208 (116.7, 385.2) | 254 (150.4, 371) | 0.960 |

PDE5I=phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, RA= right atrium, PAP= pulmonary artery pressure, CO= cardiac output, PAWP pulmonary artery wedge pressure, TPG= transpulmonary gradient, PVR= pulmonary vascular resistance,

Discussion

This retrospective study is the first to describe the long-term (>16 weeks) experience in treating SCD-PH patients with PDE5-I therapy. In this cohort, patients on chronic PDE5-I therapy were documented to have improved dyspnea and NYHA class. There was no evidence of increased hospitalizations or any mention of a marked increase in the frequency VOEs in patients while on therapy.

All patients included in this study had RHC confirmed PH prior to initiation of PDE5-I, consistent with standard diagnostic criteria for PH. The hemodynamics of this cohort are similar to that observed in prior studies of SCD-PH; a baseline mPAP of 34 mmHg with a PVR of 209.6 dynes.sec/cm5 reflective of mild-moderate PH is consistent with prior studies6,10,18,20. Moreover, nearly 80% of this population had impaired RV systolic function on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), a marker of increased disease severity. Furthermore, in our study cohort, the vast majority had pre-capillary PH prior to initiation of PDE5-I therapy. In contrast, the Walk-PHaSST study (the randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of sildenafil in SCD) did not require RHC-confirmation of PH for trial inclusion, and included patients with an elevated TRV only, suggesting that some patients who were randomized to treatment actually did not have PH6,21. In our entire cohort, we observed no improvement in pulmonary hemodynamics as measured by RHC in patients receiving PDE5-I therapy. However, only 23 (63.9%) of subjects underwent a post-treatment RHC suggesting a potential selection bias towards those with worse disease. We evaluated a subgroup of 15 patients with elevated PVR > 240 dynes/sec/cm3 at baseline reflective of severe pre-capillary PH 19. In this group, we observed an improvement in PVR and TPG, suggesting a hemodynamic improvement with PAH therapy in a select group of patients. While it is not possible to rule out that regression to the mean could be contributing to this effect, the observed improvement in PVR (124 dynes.sec/cm5) is greater than what would be predicted from this statistical model (111 dynes.sec/cm5)23. Interestingly, two of the 23 subjects with RHC data post-treatment had normalization of pulmonary pressures with a mPAP <25mmHg (based on the diagnostic criteria for PH at the time of RHC).

In contrast, no difference was observed in the TRV by echocardiography or 6MWD after therapy. There was a wide range of therapy duration in this cohort, with a median (IQR) length of documented therapy of 25 (13, 60) months. This variability of treatment time may explain the lack of impact on hemodynamics in some and exercise capacity in the group as a whole. To explore this observation, a subgroup of 16 patients who were maintained on PDE5-I therapy for at least 36 months were compared and while there was a statistically significant improvement in NYHA class (p=0.05), no improvements were noted in hemodynamic or functional outcomes (Table 4).

Alternatively, another explanation for the noted lack of objective improvement in functional capacity, echocardiography and hemodynamics may relate to concomitant left-sided heart disease, persistent anemia and the lack of 6MWD improvement due to concomitant joint disease related to avascular necrosis, the primary orthopedic complication of SCD. We included mPAP ≥ 25 mm Hg as inclusion criterion, but we did not specify pulmonary arterial wedge pressure to be less than 15 mmHg. This is problematic as 60% of patients with PH of SCD have elevated left-sided filling pressures which are also associated with increased mortality17. This phenomenon is similar to what is observed in another form of Group 5 PH, related to sarcoidosis20. We utilized the historical definition of PH (mPAP of ≥ 25 mm Hg) as part of our study design as this was the definition at the time of PDE5-I utilization. More recently, the definition has been changed to a mPAP > 20 mm Hg, but it is not yet known how this definition change alters outcomes in PH of SCD19.

It is noteworthy that in this cohort of patients, 38.2% of subjects had V/Q findings supportive of CTEPH (table 2). Sickle cell disease is a hypercoagulable state; 11–12% of patients have experienced a venous thromboembolism by the age of 40 and this frequency increases to 17% in those with severe disease, defined by 3 or more hospitalizations in the prior year24. The link between chronic thromboembolic disease and PH in SCD remains unclear. A recently published case series of 58 patients with sickle cell disease and pre-capillary PH found mismatched segmental perfusion defects on lung scintigraphy in 85% of HbSC patients and 9% of HbSS/S-β0 thal patients, respectively25. To further explore this observation, we performed a subgroup analysis of subjects diagnosed with CTEPH and following PDE5-I therapy, found no significant difference in mortality (p=0.28), or NYHA class (p=0.36) compared to subjects without evidence of CTEPH.

Table 2:

Baseline Laboratory and Hemodynamic Data

| Characteristic | No. of Patients Evaluated | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory studies | ||

| White blood cell count (X mm3) – median (IQR) | 33 | 9.1 (6.2 – 12.6) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) -median (IQR) | 33 | 8.5 (7.7 – 9.5) |

| Platelet count (X mm3) – median (IQR) | 33 | 368 (227 – 423) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) - median (IQR) | 32 | 408 (304 – 601) |

| NT-pro-BNP (pg/mL) - median (IQR) | 17 | 706 (270 – 1681) |

| B-type natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) - median (IQR) | 10 | 226 (83 – 501) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) – median (IQR) | 34 | 1.1 (0.6 – 1.5) |

| Ventilation Perfusion Scanning | 34 | |

| High Probability – no. (%) | 9 (26.5) | |

| Intermediate Probability – no. (%) | 4 (11.8) | |

| Low Probability – no. (%) | 21 (61.7) | |

| Prior Pulmonary Hypertension Therapy | 36 | |

| Epoprostenol - no. (%) | 3 (8.3) | |

| Riociguat - no. (%) | 2 (5.6) | |

| Bosentan – no. (%) | 6 (16.7) |

NT-pro- BNP= N terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide

Six subjects (16.7%) remained on PDE5-I therapy at the time of data collection. Adverse effects commonly associated with PDE5-I therapy were minimal in this cohort; 3 subjects experienced ophthalmologic complaints, and only 1 subject stopped therapy due to VOE. In this cohort of patients, 22 patients (61.1%) were on hydroxyurea therapy and 14 patients (40%) were on chronic transfusion therapy (table 1), which may have contributed to the tolerability of PDE5is. Four subjects (11.1%) elected to discontinue therapy once the results of Walk-PHaSST were published; it is unclear if they were experiencing adverse events. Seventeen subjects (47.2%) were receiving PDE5-I at the time of their death. The cause of death in these patients is unknown. As such, we are unable to speculate as to the role of PDE5-I in death, however this death rate is within the expected 5 year predicted mortality for patients with SCD-PH8–9.

The results observed in this study are similar to those obtained in the small open-labeled studies of sildenafil use in SCD-PH 12,16. Those studies demonstrated potential utility of sildenafil and served to lay a framework for the design of the multicenter randomized, placebo-controlled Walk-PHaSST study. After enrolling 74 (out of a targeted enrollment of 132) subjects, the Walk-PHaSST trial was terminated due to an increase in adverse events, primarily hospitalization for VOE14. One possible explanation for the observation of reduced VOEs in our cohort compared to Walk-PHaSST is the higher proportion of patients receiving chronic transfusion therapy in our cohort, (40% vs 5% respectively), suggesting better control of the underlying SCD. Given the longer duration of follow up in this study (median follow-up time of 25 months) and the fact that VOEs in Walk-PHaSST occurred within 16 weeks of commencing sildenafil, it is interesting that there was no mention of VOE in the records reviewed. However, it is important to note that a limitation of the retrospective study design is that data such as VOEs were not universally recorded. A major limitation of the Walk-PHaSST study was that only those patients with a TRV ≥ 3.0 m/s (24 out of 74 patients [32%]) underwent a RHC suggesting that patients without PH were randomized into the study, as the positive predictive value of a TRV ≥ 2.5 m/s for PH is only 31%18. In fact, only 24 subjects underwent RHC in that study with PH confirmed in 1318. Since our study was limited to subjects who underwent RHC prior to the initiation of PDE5-I, our findings are more generalizable to patients with hemodynamic confirmation of PH.

Our study is limited by its retrospective design and reliance on non-standardized clinical documentation. This led to missing data and the reliance on clinician practice for the ordering of studies, particularly follow-up RHCs which may only have been ordered for progression of symptoms or echocardiography. This would likely skew the data towards a null effect. In this scenario, patients exhibiting the greatest clinical improvement would be less likely to have undergone a repeat RHC which may have limited our ability to accurately assess the potential effect of PDE5-I on cardiopulmonary hemodynamics. Regardless, our data demonstrate the feasibility of PDE5-I use in a subset of the SCD PH population.

In conclusion, we present findings from a retrospective medical record review which supports the tolerability and potential efficacy of PDE5-I in a subset of patients with RHC confirmed SCD-PH. From our data, the importance of optimization of SCD management with hydroxyurea and/or chronic transfusions is essential and may be responsible for the lack of observed VOE. Our retrospective study supports the need to re-address the use of these medications prospectively in a carefully designed clinical trial focused on the patients with RHC-confirmed pre-capillary PH ideally. Design of future clinical trials in SCD must pay attention to important phenotypes and endotypes that will better stratify SCD patients allowing for more individualized care.

Significance Statement.

Sickle cell disease related pulmonary hypertension is a complex disorder with significant functional limitations and increased risk for mortality with few treatment options. We present a retrospective chart review study showing improved exercise tolerance using a drug shown to be effective for pulmonary arterial hypertension, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement:

Funding for this study was provided in part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health and Division of Intramural Research, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. APR was supported by funding from the Division of Intramural Research for NIAID, NIH. APR, ROE, SLT, NAW were all supported by funding from the Division of Intramural Research for NHLBI, NIH. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and there is no financial interest to report. We certify that the submission is original work and is not under review at any other publication.

References

- 1.Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376(9757):2018–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4)(suppl):S512–S521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potoka KP and Gladwin MT. Vasculopathy and pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L314–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller AC, Gladwin MT. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1154–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klings ES. Pulmonary hypertension of sickle cell disease: more than just another lung disease. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(1):4–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parent F, Bachir D, Inamo J, et al. A hemodynamic study of pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehari A, Gladwin MT, Tian X, et al. Mortality in adults with sickle cell disease and pulmonary hypertension. JAMA. 2012;307:1254–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehari A, Klings ES. Chronic pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. Chest. 2016;149(5):1313–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, et al. Pulmonary hypertension as a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:886–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehari A, Alam S, Tian X, et al. Hemodynamic predictors of mortality in adults with sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:840–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klings ES, Machado RF, Barst RJ, et al. An official american thoracic society clinical practice guidline: diagnosis, risk stratification, and management of pulmonary hypertension of sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(6): [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derchi G, Forni GL, Formisano F, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil in the treatment of severe pulmonary hypertension in patients with hemoglobinopathies. Haematologica. 2005; 90: 452–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barst RJ, Mubarak KK, Machado RF, et al. Exercise capacity and haemodynamics in patients with sickle cell disease with pulmonary hypertension treated with bosentan: results of the ASSET studies. Br J Haematol. 2010; 149: 426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machado RF, Barst RJ, Yovetich NA, et al. Hospitalization for pain in patients with sickle cell disease treated with sildenafil for elevated TRV and low exercise capacity. Blood. 2011;118: 855–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murad M. Hassan, et al. 2019 sickle cell disease guidelines by the American Society of Hematology: methodology, challenges, and innovations. Blood Advances. 2019;3(23):3945–3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato GJ, Gladwin MT and Steinberg MH Deconstructing sickle cell disease: reappraisal of the role of hemolysis in the development of clinical subphenotypes. Blood Reviews. 2007;21(1):37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machado RF, Martyr S, Kato GJ, et al. Sildenafil therapy in patients with sickle cell disease and pulmonary hypertension. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:445–453. 2005/July/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehari A, Alam S, Tian X, et al. Hemodynamic predictors of mortality in adults with sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(8):840–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shlobin OA, Kouranos V, Barnett SD, et al. Physiological predictors of survival in patients with sarcoidosis associated pulmonary hypertension: results from an international registry. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1901747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simoneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, et al. Haemodynamic definitinos and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niss O, Quinn CT, Lane A, et al. Cardiomyopathy with restrictive physiology in sickle cell disease. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2016;9(3):243–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis CE The effect of regression to the mean in epidemiologic and clinical studies. J of Epidemiology. 1976;105(5):493:498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunson A, Lei A, Rosenberg AS, White RH, Keegan T, Wun T. Increased incidence of VTE in sickle cell disease patients: risk factors, recurrence and impact on mortality. Br J Haematol. 2017;178(2):319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savale L, Habibi A, Lionett F, et al. Clinical phenotypes and outcomes of precapillary pulmonary hypertension of sickle cell disease. 2019;54(6):1900585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]