Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has changed the way we use and perceive online services. This study examined the influence of service quality factors during COVID-19 on individuals' intention to continue use mHealth services. A decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) approach was used to identify and analyse the relationships between service quality and individuals' intention to continue use mHealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Individuals' direct, indirect, and interdependent behaviours in relation to service quality and continues use of mHealth were studied. A total of 126 respondents were involved in this study. The results identified several associations between service quality factors and individuals' continuous use of mHealth. The most important factor found to influence users’ decision to continuously use mHealth was assurance, followed by hedonic benefits, efficiency, reliability, and content quality. The relevant cause-and-effect relationships were identified and the direction for quality improvement was discussed. The outcomes from this study can support healthcare policy makers to swiftly and widely respond to COVID-19 challenges. The findings provide fundamental insights for healthcare organisations to promote continuous use of mHealth among people by prioritising service improvements.

Keywords: mHealth, COVID-19, Service quality, Continuous intention, DEMATEL

1. Introduction

The impact of COVID-19 has been reported in different sectors in developing and developed countries. The lockdown and other governmental restrictions have [1,2] influenced people's information access behaviour and habit. The healthcare sector is one of the most affected sectors due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and certainly the public are the most affected ones. A number of studies have recently examined the impact of COVID-19 on people's behavioural responses and how these responses may shape their intentions to use healthcare services. This implies that the public are at the centre of the healthcare service delivery, and that health services should be transformed so that individuals can be continuously use them effectively [3,4]. Hospitals and healthcare service providers have been struggling to handle the increasing number of patients and to prevent nosocomial infections [5]. In addition, healthcare members are expected to maintain their performance levels during the pandemic in order to provide the necessary care to patients. In most countries, mobile health or mHealth is becoming one of the key tools for providing urgent medical helps as well as monitoring services to patients [6]. The delivery of mHealth services includes infection tracing and management, reporting, and other relevant functionalities. According to Ref. [7]; mHealth is currently used to monitor individuals with COVID-19 symptoms. It can provide a means for the detection of virus exacerbations and the utilisation of clinical interventions when needed. mHealth is also seen as an instrument for monitoring users' real time, longitudinal, and dynamic experience of the virus [8,9].

However, there are few studies that have empirically examined the service quality of mHealth and its impact on individuals' continuous intention to use it for COVID-19-related treatment or monitoring. The current literature on this topic is sparse, and the existing studies (e.g. Ref. [10], are mostly reporting the views of practitioners and healthcare professionals, with limited insight from the user perspective. In addition, there is a limited understanding of service quality provided by healthcare organisations and its impact on people's continuous use of mHealth to contain COVID-19. Our review of the literature showed a significant body of evidence to support the potential of mHealth prior to this pandemic. Despite this, the main dimensions of service quality and its relationships to the continuous intention of individuals to access mHealth services are yet to be defined. This is supported by Oliver et al. (2020) who have indicated the importance of addressing the use of mHealth in order to enable rapid deployment and scale-up of evidence based solutions.

This study aims at answering two questions: “What are the service quality factors that most impact individuals' continuous intention to use mHealth during COVID-19?” and “What are the causal relationships between these factors?” In order to answer these questions, we used a decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) approach to conceptualise the causal relationships between different service quality factors and individuals’ continuous use of mHealth. The DEMATEL approach has been used by previous studies to create an impact-relation map of certain elements, and to ascertain the level of influence of each element over the other [11,12]. Identifying the key factors contributing to mHealth continuous use among people can support healthcare policy makers to swiftly and widely respond to COVID-19 challenges. The study can also offer ways for healthcare organisations to encourage active use of mHealth among people by prioritising relevant service improvements to attract new users.

2. Literature review

The COVID-19 global pandemic has dramatically affected the way we use and perceive online services. It has transformed healthcare provision and created new demands for the use of mHealth services. The fear of a potential infection in a clinical setting has led to reduction in on-site referrals [13], and increased traffic to mHealth services. The recent COVID-19 trend requires sufficient mHealth services that balances the market demands and users' needs. mHealth technology is a mobile electronic device used for creating, storing, retrieving and transmitting data in real time in healthcare provision [14], as well as offering services such as remote monitoring, remote consultation, and personal healthcare [15,16]. Significant forms of mHealth technology include mobile devices, software platforms and mHealth applications [17]. In meeting the new health challenges (COVID-19), understanding service quality strikes as key for generating intention and sustained interest towards continued use of mHealth services.

Although, extant literature on digital health has provided some understanding on adoption and use of various eHealth technologies, gaps continue to exist in relation to the influence of quality of mHealth services on people's intention towards continued use. Despite the proliferation of mHealth apps, adoption and diffusion of health technologies remain an issue in contemporary research [18,19]. Thus, a study that assesses the quality of mHealth services and its effect on users' continuous intention to use them remains unclear. This is because, service quality assessed from user perspectives has tremendous value for the eHealth industry, safety and health of citizens in general [20,21]. In view of this, we examined how service quality of existing mHealth applications have influenced individuals' intention to continued use of services in the era of COVID-19. Existing research has underscored the fact that the quality of any information systems is highly linked to certain critical success factors. Arguments about the inclusion of service quality for the measurement of the effectiveness of IS services have gained grounds in the literature. In the technology-enabled environment, measurement of service quality differ slightly from the generic service quality found in the marketing research domain [22]. This is due to certain mHealth service attributes such as virtual consultation, ubiquity, accessibility, personalised nature, immediacy, flexibility, interactivity and mobility [14,15,23], and in particular the involvement of safety and health of individual users. Also, certain difficulties regarding the use of mHealth services such as mobile devices' structural limitations and unnecessary mental efforts needed to use services [24,25] make the need for service quality even more vital.

Previous studies on technology service quality, such as [26]; have proposed three main dimensions of service quality: platform quality, interaction quality, and outcome quality. These dimensions were part of the E-S-QUAL (electronic service quality) and E-RecS-QUAL (electronic recovery) service quality models. The literature also revealed a number of factors that fall under the E-S-QUAL dimensions such as efficiency, system availability, fulfilment, privacy, perceived value and loyalty intentions. Other factors such as responsiveness, compensation, and contact were included in the E-RecS-QUAL model. These factors were particularly useful for determining the web-site service quality. However, its major limitation was noted in the absence of hedonic benefits and their impact on user intention [25]. proposed a causal model of information quality for mobile Internet services. They found that customers assess the information quality of mobile services based on the following four key elements: 1) connection quality; 2) content quality in terms of value and usefulness; 3) interaction quality; and 4) contextual quality in terms of timeliness and access to unrestricted information regardless of time and location.

Our review showed the importance of service quality model (SERVQUAL) within the IS discipline. SERVQUAL has been widely adopted by many studies to measure and manage service quality factors such as reliability, tangibility, responsiveness, and assurance [15,27]. In addition, the DeLone and McLean (D&M) IS success model has been found to be very useful in service quality research [[27], [28], [29]]. It has been applied in several empirical studies for measuring the success of IS [15]. theorised a service quality model based on existing frameworks to understand specific mHealth service quality elements and users' intention to continued usage. They argued that users assess mHealth service quality from three main levels, namely: platform quality (system reliability, system efficiency, system availability, system flexibility, and system privacy), interaction quality (responsiveness and assurance) and outcome quality (functional benefits and emotional benefits). Despite the theoretical contribution of their study towards assessing quality of mHealth services, the lack of empirical findings to either confirm or reject the proposed relationships remains a challenge. Thus, the need for further research, in particular those that explore the cause and effect relationships between mHealth service quality and users’ intention to continuous use.

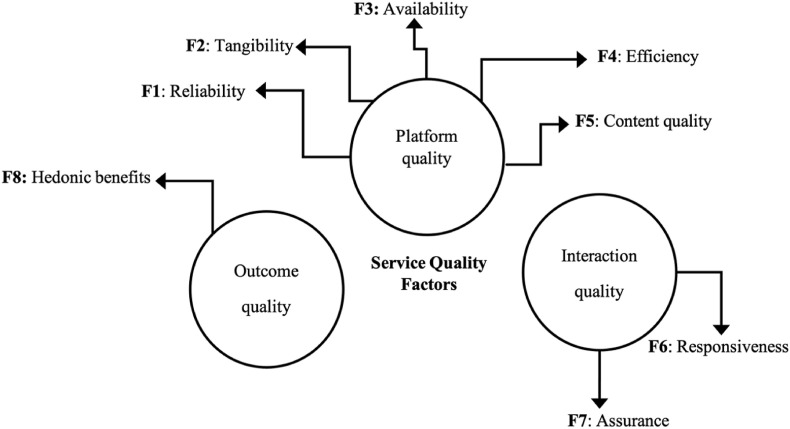

In a recent study [16], argued that existing quality dimensions for measuring the continuous usage of mHealth services are not comprehensive enough. As a result, they proposed five elements namely: content quality (confidence, utilitarian benefits and hedonic benefits), engagement (engagement and care), privacy, reliability and usability for assessing the quality of mHealth. Though the attempt to reclassify existing dimensions into new clusters appear laudable and good for research knowledge, this study is of the view that the D&M model and other models which categorises quality dimensions into systems quality, information quality and outcome quality are still valid. They provide wholistic view of IS quality as well as a much clearer pathways for understanding the causal linkages among quality elements and users' continued intention and usage of a technology. From the foregoing, we shaped this study based on existing research, particularly the D&M IS model, to explore the various components that may potentially influences users’ continuous intention to use mHealth services during the COVID-19 era. This section reviews existing literature on service quality. We follow with a discussion of the structure of service quality such as platform quality (reliability, tangibility, efficiency and content quality), interaction quality (responsiveness and assurance) and outcome quality (hedonic benefits) (see Fig. 1 ). Lastly, we explored the interaction between perceived quality standards of mHealth services and intention to use.

Fig. 1.

The proposed service quality factors.

2.1. Platform quality

In a mHealth context, platform quality is considered as an authentic determinant of service quality [30]. Platform quality mostly linked to satisfaction, usage intention, and system usage. It plays a vital role in determining the technical success of the system, mainly by assessing the system quality based on certain key elements: reliability, tangibility, availability, efficiency and content.

2.1.1. Reliability

Our review of the literature showed that individuals' opinions on service quality are somehow based on the reliability of the IS [16,31]. The reliability of mHealth can be defined as the probability that a service will operate without failure for a stated period of time [32,33]. have indicated that the reliability of a service can be the key factor driving individuals' willingness to use the system [34]. outlined the association between the reliability of a system and the intention of users to use cloud services. Based on these, we considered examining the impact of service reliability during COVID-19 on individuals’ continued usage of mHealth.

2.1.2. Tangibility

Our review also showed the role of tangibility in assessing the presence of physical offices, equipment, personnel and communication materials [16,29]. According to Ref. [17]; who captured tangibility as facilitating conditions, the existing support of mHealth infrastructure can influence individuals' usage intention significantly. The tangibility of mHealth services can be measured using observable characteristics such as testing options/method for COVID-19, contact tracing platforms, diagnosis and treatment plans. In a healthcare context [35], found that tangibility of care services can significantly shape individuals’ behavioural intention to use technology.

2.1.3. Availability

Availability of a service refers to the availability of functionalities for tracing, reporting, and treating COVID-19 symptoms at anytime and anywhere. The literature showed that the replacement of bureaucratic requisition and approval process with rapid IT-based systems can potentially promote individuals' perceptions of service availability [36]. In a healthcare context [37], linked service availability to users' perception of the system speed, ease of use, legibility of the data, and the provided support. The relationship between service availability and continuous intention to use mHealth is yet to be understood. The availability of Internet services, the knowledge of this availability, the preference to use digital channels, and the ability and experience to do this were among the fundamental conditions for Internet usage. Many previous studies (e.g. Refs. [[38], [39], [40]], have addressed the importance of availability in regulating individuals’ behavioural intentions.

2.1.4. Efficiency

Efficiency refers to the technical performance of a system [26,27]. Efficiency can be linked to individuals' perception of the system's potential to save money, time, and efforts in the provision of public service [33]. The same can be said to the role of mHealth efficiency in the context of this study. Review of the literature revealed how system efficiency can significantly influence people's usage intention of technology. For example [41], found a significant relationship between system efficiency and intention to continue using the system in a healthcare setting. Yet, evidence about the impact of mHealth efficiency on individuals' continued usage is still lacking.

2.1.5. Content quality

Health content quality is a representation of consistency and completeness of information provided by healthcare providers [25]. Previous research suggests that the extent to which health information is personalised, easy to understand and secure, can contribute to users' quality perception. This is when users develop unique feelings of importance for their health needs, which can influence their intention to use the service [27,42]. However, the quality of mHealth information is critical and deserve much scrutiny since human lives are involved and any potential errors could be fatal for users. The impact of information/content quality of mobile services on individuals’ usage intention has been supported by many previous studies (e.g., Refs. [16,43,44].

2.2. Interaction quality

Interaction quality of IS services is determined by the overall support delivered by the service provider. In most instances, such support services are either outsourced, or delivered through IS department or Internet service providers [27]. Both responsiveness and assurance have been noted in the literature as critical elements of interaction quality of e-technology [15].

2.2.1. Responsiveness

Responsiveness in the context of this study refers to the readiness of mHealth to respond to users' legitimate expectations regarding a set of factors related tracing, monitoring, and treating COVID-19 cases. According to Ref. [45]; it might be difficult to identify objective indicators for assessing perceived responsiveness of health systems. Thus, the responsiveness of healthcare services can be measured subjectively, by inquiring into individuals' perceptions about their experience with the health systems. We note responsiveness as a critical factor for determining users' intention and continued use of health services [46]. This is because, users’ initial access to prompt and quality care that satisfies their health needs are directly proportional to intention and continuous usage of the service.

2.2.2. Assurance

Assurance is aimed at providing enough organisational competence [16,27]. In the context of this study, it refers to the ability of mHealth courtesy services to inspire trust and confidence among users. In addition, literature suggests that the site reputation in terms of products or services it offers, clear and truthful information are relevant quality measures [26]. In a study by Ref. [47]; perceived source credibility was used for understanding the extent to which mHealth service users believe information source is reliable, competent and trustworthy. According to Ref. [48]; assurance in the service environment is considered a fundamental constituent to long-term relationships and loyalty. This is why we believe that healthcare providers should be specialists in the type of services they offer to people. Thus, the relationship between mHealth service assurance and individuals’ continuous use is worth investigation.

2.3. Outcome quality

Individuals' perceptions of system and service quality are important determinants of outcome quality. According to Ref. [15]; the overall benefits users accrue from using mHealth services can constitute their perception of outcome qualities. In a mHealth context, it reflects the level of completeness and accuracy of information and how they support users’ health needs.

2.3.1. Hedonic benefits

Outcome quality was categorized into two dimensions, namely: functional (pragmatic) and emotional benefits [15,24]. [47] in their study employed the term perceived enjoyment (intrinsic motivation) to represent emotional benefits a user may receive from using mHealth services. It is instructive to note their study engaged these dimensions as facilitators of the relationship between technological and psychological characteristic and usage intention. Aside from the utilitarian benefits of mHealth services, research suggests that individuals are drawn to IS due to the positive feelings or experiences (hedonic benefits) that the use of technologies arouses [32]. indicated that individuals’ perception of hedonic value may significantly influence their willingness to use technology.

Despite previous efforts to improve healthcare service quality, there seems to be a limited understanding of the relationship between the eight dimensions of service quality mentioned above and individuals' continued usage of mHealth services [16]. in their study argued that poor service quality remains a major hindrance towards continued use of mHealth services. To proffer solution to this trend, critical quality factors that influence individuals' continuous intention to use mHealth services were examined in this study. As such, we proposed a number of associations between service quality and individuals’ continuance intention to use mHealth services (see Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n:126).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 60 (47.6%) |

| Female | 66 (52.4%) |

| Age | |

| 18-23 | 9 (7.2%) |

| 24-29 | 12 (9.5%) |

| 75 (59.5%) | |

| >35 | 30 (23.8%) |

| Education level | |

| Bachelor | 16 (12.6%) |

| Master | 76 (60.4%) |

| PhD | 34 (27%) |

| Study disciplines | |

| Science | 83 (66%) |

| Social Science | 43 (34%) |

3. Method

This study examined the associations between service quality dimensions and factors (see Fig. 1) such as platform quality (reliability (F1), tangibility (F2), availability (F3), efficiency (F4), content quality (F5)), interaction quality (responsiveness (F6) and assurance (F7)), and outcome quality (hedonic benefits (F8)).

3.1. Sample and procedure

In this study, the extracted service quality factors from the literature on people's intention to use technology were used to construct a structured set of questions. We used a convenience sampling method to recruit individuals from four universities. A total of 300 invitation emails were sent individually to a pool of university students who had experience using mHealth on issues related to COVID-19 (e.g., monitoring and diagnosis). After three attempts, we were able to recruit 126 mHealth users (60 males and 66 females). Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the respondents enrolled in this study. A total of 75 respondents were within the age group 30–35 years, followed by > 35 years (n: 30), 24–29 years (n: 12), and 18–23 (n: 9) respectively. The majority of respondents (n: 76) were enrolled in master's programmes, while 34 respondents were enrolled in PhD programmes.

The respondents were emailed a structured set of questions (Google Forms) with a guide on how to assess the level of the influence of each factor on others. A definition of each factor was provided with an example of its application in the context of this study. Table 2 summarises the main characteristics of mHealth services that the respondents used. From the table, it can be noticed that the majority of respondents used mHealth apps that were made available through the Google Play platform (n: 86), followed by iOS (n:32) and both Google and iOS (n: 8). In addition, the majority of respondents used free governmental mHealth services (n: 118). The respondents also reported that they used mHealth services in order to perform contact tracing (n: 58), view health updates (n: 37), receive health advice (n: 21), and manage health symptoms (n: 10).

Table 2.

mHealth characteristics (n:126).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Operating System | |

| iOS store only (Apple) | 32 (25.4%) |

| Google Play only (Android) | 86 (68.3%) |

| Both iOS and Google | 8 (6.3%) |

| Cost | |

| Free | 118 (93.7%) |

| Free for full access | 3 (2.3%) |

| Subscription (monthly or annual) | 5 (4%) |

| Purpose of use | |

| Contact tracing | 58 (46%) |

| Health advice | 21 (16.6%) |

| Health updates | 37 (29.4) |

| Managing health symptoms | 10 (8%) |

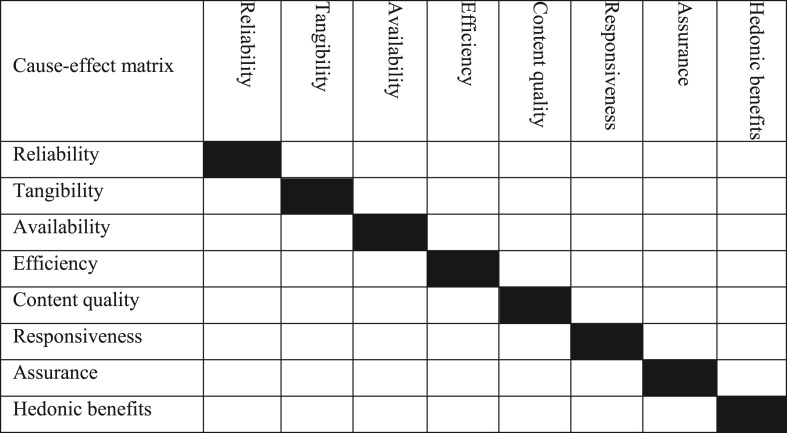

All the respondents were asked to identify the weight/level of influence each service quality factor has on other factors (see Table 3 ). Here we used a scale of 0 (no influence), 1 (very low influence), 2 (low influence), 3 (high influence), and 4 (very high influence). We coded all the responses individually to come out with the cause-effect relationship diagram, followed by the normalization step. The main steps used to generate the cause-effect map are discussed in the following subsection.

Table 3.

The proposed pairwise relationships.

Instructions for filling out the index: 0 = No influence; 1 = Very low influence; 2 = Low influence; 3 = High influence; and 4 = Very high influence.

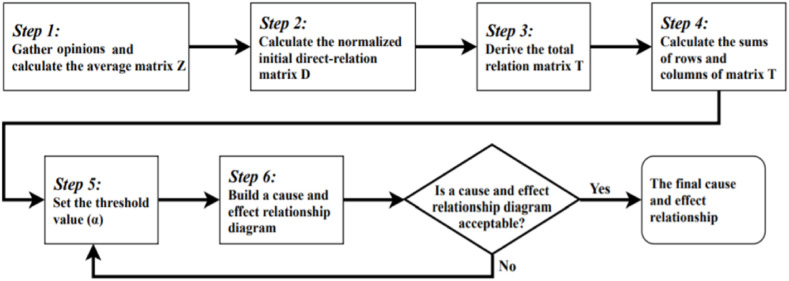

3.2. DEMATEL method

The DEMATEL approach was originally proposed by Battelle Memorial Association in Geneva. This approach has been applied in various disciplines (e.g., management, business, education, and healthcare) to examine relationships among certain evaluation criteria [49]. This approach consists of several steps that lead to the final value (see Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

DEMATEL steps.

Based on the literature, we were able to identify the key service quality factors that may influence individuals’ continuous intention to use mHealth. These factors are outlined in Table 4 .

Step 1

Calculating direct relation matrix A.

Table 4.

Service quality factors influencing continuous intention to use mHealth.

| Factors | Description |

|---|---|

| F1 | Reliability |

| F2 | Tangibility |

| F3 | Availability |

| F4 | Efficiency |

| F5 | Content quality |

| F6 | Responsiveness |

| F7 | Assurance |

| F8 | Hedonic benefits |

After collecting responses concerning individuals’ opinions about the proposed relations (see Table 5 ), the direct relation matrix was then calculated. This was achieved by identifying the level of influence that the element i in the matrix row exerts over the element j in the matrix column, in which the influence that the element i have on the element j.

Table 5.

Scores of the relations.

| Type of relations between variables | Influence score |

|---|---|

| No influence | 0 |

| Very low influence | 1 |

| Low influence | 2 |

| High influence | 3 |

| Very high influence | 4 |

The matrix A is found by averaging all scores received from individuals.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Here H refers to the number of respondents in this study.

Step 2

Normalizing the direct-relation matrix.

In this step, we calculated the direct relationship matrix X between the processed responses from the previous step by using the following formulas:

| (3) |

| (4) |

The sum of each row j of the matrix A is a representation of the direct effects that factor i has on other factors, here is used to represent the direct effects of one factor on others.

Step 3

Calculating the total-relation matrix T.

Once the normalized direct-relation X was calculated, the total-relation matrix T was estimated by applying the following formula (I refers to the identity matrix):

| (5) |

Step 4

Producing the causal diagram.

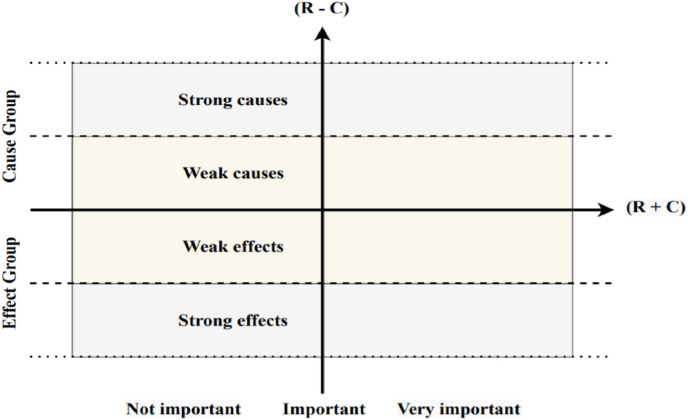

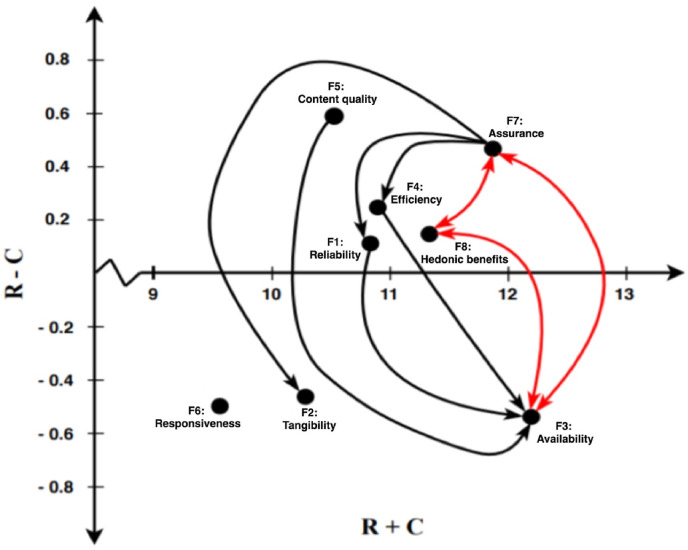

The process we followed to generate the causal diagram for the impact of service quality on users’ continuous intention to use mHealth was based on measuring vector R (sum of rows) and vector C (sum of columns). The causal graph was shaped by using R + C as the horizontal axis and R–C as the vertical axis. It is worth mentioning that the produced graph can help define the relationships between the factors and identification of those most important and influential (see Fig. 3 ). The higher the value of (R + C), the higher the degree of importance of a given factor in the decision-making process.

Fig. 3.

The causal graph.

In addition, the value of R–C is a representation of the general nature of each relation. If the value of each relation is greater than 0, it dominates over other values, if it is negative, it is dominated by other variables. Also, the location of the result on the scatterplot in the causal-effect plot can be used to determine whether a given variable is a cause or an effect [50].

| (6) |

| (7) |

Step 5

Setting up the threshold value (α) and obtaining the causal-relation map.

The process of understanding structural relations within variables was explored in this study by keeping the complexity of the whole causal-relation map at a manageable level. Here, we set the threshold value (α) in order to filter out negligible effects in matrix T. Only the factors whose effect in matrix T that are greater than the threshold value were shown in an inner dependence matrix. We identified the total threshold value by adding the mean (0.68) and the SD (0.09) of the elements in total matrix T, α = 0.77 (see Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 ).

Table 6.

Averaged cause-effect matrix.

| Averaged Cause-effect matrix | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.00 | 2.34 | 4.00 | 3.23 | 2.31 | 2.79 | 3.51 | 3.11 |

| F2 | 2.11 | 0.00 | 3.12 | 2.67 | 2.75 | 2.20 | 3.10 | 2.90 |

| F3 | 3.53 | 3.10 | 0.00 | 3.42 | 2.87 | 2.74 | 3.42 | 3.75 |

| F4 | 2.90 | 2.76 | 3.54 | 0.00 | 3.57 | 2.50 | 3.63 | 2.78 |

| F5 | 3.10 | 2.89 | 3.78 | 2.67 | 0.00 | 2.78 | 3.10 | 3.40 |

| F6 | 2.10 | 2.53 | 3.10 | 2.78 | 2.31 | 0.00 | 2.10 | 2.56 |

| F7 | 3.56 | 3.86 | 3.94 | 3.64 | 3.10 | 2.90 | 0.00 | 3.50 |

| F8 | 3.56 | 3.42 | 3.90 | 2.40 | 2.30 | 3.56 | 3.57 | 0.00 |

Table 7.

Normalized cause-effect matrix.

| Normalized cause-effect matrix | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| F2 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| F3 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| F4 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| F5 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| F6 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| F7 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.14 |

| F8 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

Table 8.

Total cause-effect matrix.

| Total Cause-effect matrix | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.72 |

| F2 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.65 |

| F3 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| F4 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.72 |

| F5 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.73 |

| F6 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 0.60 |

| F7 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.81 |

| F8 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.64 |

4. Results and Discussion

The role of certain quality dimensions in stimulating users' continuance intention to use mHealth services has been rarely investigated, especially in the age of pandemic. Our review of the literature shed light on 8 service quality factors that may influence patients' continuous intention to use mHealth, which categorized under– platform quality (reliability, tangibility, availability, efficiency, and content quality), interaction quality (responsiveness and assurance), and outcome quality (hedonic benefits). After identifying the total cause-effect matrix, we were able to calculate the relationships between factors by calculating the row values (R) and column values (C) as shown in Table 9 . According to Fig. 4 , this study found a potential impact of certain factors on individuals’ continuous intention to use mHealth. In addition, a number of associations were identified between the study factors. Our results reported the main (prominent) factors of continuous intention to use mHealth and the main relationships amongst these factors. In Fig. 4, the interrelated lines between the factors were used as an indication of the relationship from the influencing factor to the affected one, whereas the two-way arrows (double-sided) was used to represent the mutual influence between these factors.

Table 9.

The resulted relations between factors.

| Factors | R | C | R + C | R–C | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 5.48 | 5.38 | 10.86 | 0.10 | Cause |

| F2 | 4.91 | 5.37 | 10.28 | −0.47 | Effect |

| F3 | 5.81 | 6.36 | 12.18 | −0.55 | Effect |

| F4 | 5.57 | 5.35 | 10.92 | 0.22 | Cause |

| F5 | 5.56 | 4.97 | 10.53 | 0.59 | Cause |

| F6 | 4.55 | 5.03 | 9.57 | −0.48 | Effect |

| F7 | 6.17 | 5.72 | 11.90 | 0.45 | Cause |

| F8 | 5.76 | 5.63 | 11.38 | 0.13 | Cause |

Fig. 4.

The DEMATEL map.

According to Ref. [51]; a full interpretation of how the cause factors group can influence the effect factors group should be reported. This study found that the main service quality factors associated with the continuous intention of users to use mHealth during COVID-19 were assurance (F7), hedonic benefits (F8), efficiency (F4), reliability (F1), and content quality (F5), with values of 11.90, 11.38, 10.92, 10.53, and 10.86, respectively. A key point is that if any of the factors are not associated with any other factors, it means that their cause/effect is independent from other factors. Based on this, the factor with least effect was responsiveness (F6), with a value of −0.48. In addition, our results showed that the main net causers in this study were assurance (F7), efficiency (F4), reliability (F1), and content quality (F5), whereas factors related to efficiency (F4), reliability (F1), availability (F3), and tangibility (F2) were the net receiver based on the value of difference (r−c, presented in Table 8). Other factors, such as assurance (F7), hedonic benefits (F8), and availability (F3), were net causers and receivers.

Our DEMATEL map shown in Fig. 4 indicated that the substantial causal factor of individuals' continuous intention to use mHealth during the COVID-19 pandemic was assurance of mHealth quality. Consequently, more attention should be given by healthcare decision makers to this dimension. This finding is supported by the recent calls in the literature on the importance of quality assurance of diagnostic tests, drugs, and vaccines and their role in stimulating people's use of technology [52]. Interestingly, this study found that assurance, hedonic benefits and availability of service were interchangeability influencing users' decision to continuously use mHealth for COVID-related updates and emergencies. The literature showed few insights about the association between mHealth quality assurance, availability of service, and its hedonic value. This can be linked to the previously employed methods, which lack the absence of depth examinations of causality between factors in a context-specific manner. The assurance of service quality was found to have a direct relation with the efficiency of mHealth services. A number of studies (e.g. Refs. [53,54], have addressed the role of quality assurance in increasing the efficiency of a service [55]. indicated that both quality assurance and efficiency are important in expanding the care system and services. However, our review showed limited evidence on how this relationship influences individuals' continuous intention to utilise health-related technologies. In fact, most previous studies on service quality have investigated how efficiency and quality assurance are associated with individuals' satisfaction (e.g. Refs. [56,57], and intention to use services (e.g., Ref. [35]. Therefore, this finding offers new evidence on the nature of quality assurance in increasing mHealth efficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic. The direct relationship between assurance and the reliability of mHealth was found to influence users' continuous use of the service. This finding is in agreement with [58] who reported the potential of mobile assurance and reliability in predicting the intention to use a service. Quality assurance and the tangibility of a service was found to significantly contribute to the continuous intention of people to use mHealth. This finding is supported by the work of [59] who reported significant correlation between assurance and tangibility in the use of e-services. Although many previous studies have investigated quality assurance in different contexts, there is still a need for more research about its role in stimulating individuals' use of technology [60]. Healthcare providers should use effective strategies– by improving skills through continuous integration of relevant functionalities– to attract and sustain individuals for a lifelong relationship.

Our results also showed the impact of hedonic benefits on individuals' intention to continuously use mHealth services during the pandemic. This is in line with previous studies (e.g. Refs. [61,62], which have shown a positive relationship between the perceived hedonic benefits and intention to use a system [63]. assume that hedonic benefits are sub-goals that can drive individuals to attain higher goals. Thus, users are more likely to continue use mHealth services in the future when they develop a positive perception about the service. The same can be mirrored to the impact of efficiency on the continuous intention to use mHealth. This is supported by the literature (e.g. Refs. [41,64,65], in which efficiency of a service was found to compliment users’ intention to use e-services. Therefore, to provide the necessary services to users, service providers may need to improve their service efficiency by continuous adoption of innovative technologies [66]. The DEMATEL map also showed a direct relationship between efficiency and availability of mHealth. This relationship depends on the accessibility of the service and time of access.

The reliability of a service was found to significantly influence users' continuous intention to use mHealth during COVID-19 pandemic. This is in line with previous efforts, such as [67,68]; which indicated the value of service reliability on users' use of available resources and the variability of service attributes. The perception of users to mHealth may also change based on their perception of improvement in reliability and availability. This association was found in this study to favour one's continuous use of mHealth services. Meanwhile, this study found a significant influence of content quality on users' use of mHealth during the pandemic. The literature revealed a number of evidence in relation to this impact. For example [69,70], have discussed the positive impact of content quality on users' use of e-services, mainly through knowledge integration. This led some studies (e.g. Ref. [71], to propose managing the platform's content periodically, so to offer a process of learning and knowledge integration to users. From these, it can be said that service quality factors may differently influence the continuous intention of people to use mHealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings also revealed new relations between service quality determinants and individuals' use of mHealth.

5. Implications

The identified relationships between different service quality factors can enable health decision makers and government to identify the most influential factors on the use of mHealth, thus taking early measures to increase the efficiency of their quality of service. From a theoretical perspective, this study adds to previous models on service quality (e.g., E-RecS-QUAL, E-S-QUAL, and SERVQUAL) in that it identified the core and secondary factors of users' perceptions toward the current mHealth services. This study also reveals new associations between service quality determinants and individuals' use of healthcare technologies. For example, the association between quality assurance and users’ intention to use mHealth services extends the D&M model and addresses some of the issues that may affect the general quality of healthcare services. From a practical perspective, understanding the relationships between certain service quality factors of mHealth can help health decision makers to respond appropriately to challenges posed by COVID-19. For example, health decision makers can pay more attention to the assurance of service quality by ensuring their services are free of breach of confidentiality, when one needs it, especially in emergency situations.

6. Limitations and future directions

Despite the listed implications, there are still some unavoidable limitations that needs further investigation. For example, this study was limited to certain service quality factors (platform, interaction, and outcome). In addition, empathy was not an important aspect in this study because the interaction between users and healthcare specialist through mHealth do not offer individualized, caring-based interventions for patients. We also faced some difficulties in recruiting a large and representative sample of individuals with experience in using mHealth apps for tracing, reporting, and treating COVID-19. The findings from this study might not be generalized to the general population since the participants were representatives of educated young adults. Therefore, scholars in the future may further recruit a more diverse and heterogeneous sample of individuals to provide an in-depth understanding of the various relationships between the identified service quality factors. Meanwhile, future works may pay more attention to possible interrelationships between individuals’ demographic background and their perceptions of mHealth service quality. This may involve applying other data collection and analysis methods to find the causal relations of other different factors that were not included in this work.

7. Conclusion

This study used the DEMATEL approach to reveal new relationships between the different service quality factors affecting users' continuous intention to use mHealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that five core factors can potentially influence individuals' use of mHealth services, these were: assurance, hedonic benefits, efficiency, reliability, and content quality. While other factors such as availability and tangibility were found to be primarily associated with the core factors. The study also revealed new associations between these factors and people's use of mHealth services. The assurance and availability of mHealth services were found to be very important in shaping individuals' use of health technologies during COVID-19. These findings add new knowledge to the literature about how service quality can influence users' use of health technologies during the time of crisis.

Author statement

Ahmed Ibrahim Alzahrani & Hosam Al-Samarraie: Conceptualization; Hosam Al-Samarraie, Atef Eldenfria, and Ahmed Ibrahim Alzahrani: data analysis; Joana Dodoo: Literature review; Ahmed Ibrahim & Nasser Alalwan: Results and Discussion; All authors: Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2021/157), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1.Davalbhakta S., Advani S., Kumar S., Agarwal V., Bhoyar S., Fedirko E., Misra D.P., Goel A., Gupta L., Agarwal V. A systematic review of smartphone applications available for corona virus disease 2019 (COVID19) and the assessment of their quality using the mobile application rating scale (MARS) J. Med. Syst. 2020;44(9):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10916-020-01633-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tebeje T.H., Klein J. 2020. Applications of E-Health to Support Person-Centered Health Care at the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemedicine and E-Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamulegeya L.H., Bwanika J.M., Musinguzi D., Bakibinga P. Continuity of health service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of digital health technologies in Uganda. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2020;35(43) doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitelaw S., Mamas M.A., Topol E., Van Spall H.G. Applications of digital technology in COVID-19 pandemic planning and response. The Lancet Digital Health. 2020;2:e435–e440. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tracy D.K., Tarn M., Eldridge R., Cooke J., Calder J.D., Greenberg N. What should be done to support the mental health of healthcare staff treating COVID-19 patients? Br. J. Psychiatr. 2020;217(4):537–539. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams S.Y., Adeyemi S.O., Eyitayo J.O., Odeyemi O.E., Dada O.E., Adesina M.A., Akintayo A.D. Mobile health technology (mhealth) in combating COVID-19 pandemic: use, challenges and recommendations. European Journal of Medical and Educational Technologies. 2020;13(4) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adans-Dester C.P., Bamberg S., Bertacchi F.P., Caulfield B., Chappie K., Demarchi D., Erb M.K., Estrada J., Fabara E.E., Freni M. Can mHealth technology help mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic? IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology. 2020;1:243–248. doi: 10.1109/OJEMB.2020.3015141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attipoe-Dorcoo S., Delgado R., Gupta A., Bennet J., Oriol N.E., Jain S.H. Mobile health clinic model in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned and opportunities for policy changes and innovation. Int. J. Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01175-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vafea M.T., Atalla E., Georgakas J., Shehadeh F., Mylona E.K., Kalligeros M., Mylonakis E. Emerging technologies for use in the study, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with COVID-19. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2020;13(4):249–257. doi: 10.1007/s12195-020-00629-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zamberg I., Manzano S., Posfay-Barbe K., Windisch O., Agoritsas T., Schiffer E. A mobile health platform to disseminate validated institutional measurements during the COVID-19 outbreak: utilization-focused evaluation study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 2020;6(2) doi: 10.2196/18668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al‐Samarraie H., Eldenfria A., Dodoo J.E., Alzahrani A.I., Alalwan N. Packaging design elements and consumers' decision to buy from the Web: a cause and effect decision‐making model. Color Res. Appl. 2019;44(6):993–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alzahrani A.I., Al-Samarraie H., Eldenfria A., Alalwan N. A DEMATEL method in identifying design requirements for mobile environments: students' perspectives. J. Comput. High Educ. 2018;30(3):466–488. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behar J.A., Liu C., Tsutsui K., Corino V.D., Singh J., Pimentel M.A., Karlen W., Warrick P., Zaunseder S., Andreotti F. 2020. Remote Health Monitoring in the Time of COVID-19. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.08537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oppong E., Hinson R.E., Adeola O., Muritala O., Kosiba J.P. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence; 2018. The Effect of Mobile Health Service Quality on User Satisfaction and Continual Usage; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akter S., D'Ambra J., Ray P. 2010. User Perceived Service Quality of mHealth Services in Developing Countries. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim K.-H., Kim K.-J., Lee D.-H., Kim M.-G. Identification of critical quality dimensions for continuance intention in mHealth services: case study of onecare service. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019;46:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng F., Guo X., Peng Z., Zhang X., Vogel D. The routine use of mobile health services in the presence of health consciousness. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019;35:100847. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balapour A., Reychav I., Sabherwal R., Azuri J. Mobile technology identity and self-efficacy: implications for the adoption of clinically supported mobile health apps. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019;49:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duarte P., Pinho J.C. A mixed methods UTAUT2-based approach to assess mobile health adoption. J. Bus. Res. 2019;102:140–150. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Botti A., Monda A. Sustainable value co-creation and digital health: the case of trentino eHealth ecosystem. Sustainability. 2020;12(13):5263. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitsios F., Stefanakakis S., Kamariotou M., Dermentzoglou L. E-service Evaluation: user satisfaction measurement and implications in health sector. Comput. Stand. Interfac. 2019;63:16–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKecnie S., Ganguli S., Roy S.K. Generic technology‐based service quality dimensions in banking. Int. J. Bank Market. 2011;29:168–189. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajak M., Shaw K. Evaluation and selection of mobile health (mHealth) applications using AHP and fuzzy TOPSIS. Technol. Soc. 2019;59:101186. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biduski D., Bellei E.A., Rodriguez J.P.M., Zaina L.A.M., De Marchi A.C.B. Assessing long-term user experience on a mobile health application through an in-app embedded conversation-based questionnaire. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020;104:106169. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chae M., Kim J., Kim H., Ryu H. Information quality for mobile internet services: a theoretical model with empirical validation. Electron. Mark. 2002;12(1):38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parasuraman A., Zeithaml V.A., Malhotra A. ES-QUAL: a multiple-item scale for assessing electronic service quality. J. Serv. Res. 2005;7(3):213–233. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delone W.H., McLean E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003;19(4):9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alzahrani A.I., Mahmud I., Ramayah T., Alfarraj O., Alalwan N. Modelling digital library success using the DeLone and McLean information system success model. J. Librarian. Inf. Sci. 2019;51(2):291–306. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delone W.H., Mclean E.R. Measuring e-commerce success: applying the DeLone & McLean information systems success model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2004;9(1):31–47. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotfi F., Fatehi K., Badie N. 2020. An Analysis of Key Factors to Mobile Health Adoption Using Fuzzy AHP. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shamdasani P., Mukherjee A., Malhotra N. Antecedents and consequences of service quality in consumer evaluation of self-service internet technologies. Serv. Ind. J. 2008;28(1):117–138. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsiao K.-L., Huang T.-C., Chen M.-Y., Chiang N.-T. Understanding the behavioral intention to play Austronesian learning games: from the perspectives of learning outcome, service quality, and hedonic value. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2018;26(3):372–385. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y., Shang H. Service quality, perceived value, and citizens' continuous-use intention regarding e-government: empirical evidence from China. Inf. Manag. 2020;57(3):103197. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mir M.S. International Islamic University Malaysia; 2019. Cloud Computing Adoption Model Based on IT Officers Perception in Malaysian Public Education Institutions. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aliman N.K., Mohamad W.N. Linking service quality, patients' satisfaction and behavioral intentions: an investigation on private healthcare in Malaysia. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sci.s. 2016;224:141–148. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Croom S., Johnston R. Improving user compliance of electronic procurement systems: an examination of the importance of internal customer service quality. Int. J. Value Chain Manag. 2006;1(1):94–104. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spil T.A., Katsma C.P., Stegwee R.A., Albers E.F., Freriks A., Ligt E. 2010 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2010. Value, Participation and Quality of Electronic Health Records in the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almaiah M.A., Man M. Empirical investigation to explore factors that achieve high quality of mobile learning system based on students' perspectives. Eng. Science Technol. Int. J. 2016;19(3):1314–1320. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Askari M., Klaver N.S., van Gestel T.J., van de Klundert J. Intention to use medical apps among older adults in The Netherlands: cross-sectional study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(9) doi: 10.2196/18080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ratanavilaikul B. Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions in the logistic industry. AU Journal of Management. 2012;10(2):63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadoughi F., Khoshkam M., Farahi S.R. Usability evaluation of hospital information systems in hospitals affiliated with Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Health Inf. Manag. 2012;9(3):310–317. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qudah B., Luetsch K. The influence of mobile health applications on patient-healthcare provider relationships: a systematic, narrative review. Patient Educ. Counsel. 2019;102(6):1080–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma S.K., Sharma M. Examining the role of trust and quality dimensions in the actual usage of mobile banking services: an empirical investigation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019;44:65–75. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sohn K.-S. An empirical study of factors influencing intention to use smartphone applications. J. Korea Aca. Indus. cooperation Soc. 2012;13(2):628–635. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valentine K. Springer; 2003. Psychoanalysis, Psychiatry and Modernist Literature. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernández-Pérez Á., Jiménez-Rubio D., Robone S. The effect of freedom of choice on health system responsiveness. Evidence from Spain. 2019;1:1–22. http://www.york.ac.uk/economics/postgrad/herc/hedg/wps/ [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu F., Ngai E., Ju X. Understanding mobile health service use: an investigation of routine and emergency use intentions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019;45:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Kervenoael R., Hasan R., Schwob A., Goh E. Leveraging human-robot interaction in hospitality services: incorporating the role of perceived value, empathy, and information sharing into visitors' intentions to use social robots. Tourism Manag. 2020;78:104042. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheng-Li S., Xiao-Yue Y., Hu-Chen L., Zhang P. Mathematical Problems in Engineering; 2018. DEMATEL Technique: A Systematic Review of the State-Of-The-Art Literature on Methodologies and Applications. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aldowah H., Al-Samarraie H., Alzahrani A.I., Alalwan N. Factors affecting student dropout in MOOCs: a cause and effect decision‐making model. J. Comput. High Educ. 2019:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fontela E., Gabus A. Battelle Geneva Research Center; Switzerland, Geneva: 1976. The DEMATEL Observer, DEMATEL 1976 Report. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newton P.N., Bond K.C., Adeyeye M., Antignac M., Ashenef A., Awab G.R., Bannenberg W.J., Bower J., Breman J., Brock A. COVID-19 and risks to the supply and quality of tests, drugs, and vaccines. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(6):e754–e755. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30136-4. [Record #395 is using a reference type undefined in this output style.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mantas J. Quality assurance and effectiveness of the medication process through tablet computers? Quality of Life Through Quality of Information: Proceedings of MIE2012. 2012;180:348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salihu A., Metin H., Hajrizi E., Ahmeti M. The effect of security and ease of use on reducing the problems/deficiencies of electronic banking services. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2019;52(25):159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rinke N., von Gösseln I., Kochkine V., Schweitzer J., Berkhahn V., Berner F., Kutterer H., Neumann I., Schwieger V. Simulating quality assurance and efficiency analysis between construction management and engineering geodesy. Autom. ConStruct. 2017;76:24–35. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salihu A., Metin H. The impact of services, assurance and efficiency in customer satisfaction on electronic banking services offered by banking sector. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2017;22(3):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xhema J., Metin H., Groumpos P. Switching-costs, corporate image and product quality effect on customer loyalty: kosovo retail market. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2018;51(30):287–292. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meharia P. Assurance on the reliability of mobile payment system and its effects on its'use: an empirical examination. Acc. Manag. Info. Sys. 2012;11(1):97. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jaiswal B., Saba M.N.U. A critical evaluation of e-services provided by indian commercial banks. Int. J. Business Adminis. Res. Rev. 2015;1(11):226–230. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choi S.-Y., Ahn S.-H. Quality assurance of distance education in korea. Int. J. Adv. Comp. Techn. 2010;2(3):155–162. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aguiar Castillo L., Rufo Torres J., De Saa Pérez P., Pérez Jiménez R. 2018. How to Encourage Recycling Behaviour? the Case of WasteApp: a Gamified Mobile Application. Sustainability (Switzerland) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ayeh J.K., Au N., Law R. Predicting the intention to use consumer-generated media for travel planning. Tourism Manag. 2013;35:132–143. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chiu C.M., Wang E.T., Fang Y.H., Huang H.Y. Understanding customers' repeat purchase intentions in B2C e‐commerce: the roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014;24(1):85–114. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khatoon S., Zhengliang X., Hussain H. The Mediating Effect of customer satisfaction on the relationship between Electronic banking service quality and customer Purchase intention: evidence from the Qatar banking sector. Sage Open. 2020;10(2) 2158244020935887. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tang J.-t. E., Tang T.-I., Chiang C.-H. Blog learning: effects of users' usefulness and efficiency towards continuance intention. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2014;33(1):36–50. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin C.-Y. Determinants of the adoption of technological innovations by logistics service providers in China. Int. J. Technol. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2008;7(1):19–38. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim D., Kang S., Moon T. Technology acceptance and perceived reliability of realistic media service. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2015;8(25):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sulistyowati W.A., Alrajawy I., Yulianto A., Isaac O., Ameen A. Intelligent Computing and Innovation on Data Science. Springer; 2020. Factors contributing to E-government adoption in Indonesia—an extended of technology acceptance model with trust: a conceptual framework; pp. 651–658. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alshurideh M.T., Salloum S.A., Al Kurdi B., Monem A.A., Shaalan K. Understanding the quality determinants that influence the intention to use the mobile learning platforms: a practical study. Int. J. Int. Mobile Technol. (IJIM) 2019;13(11):157–183. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Calisir F., Altin Gumussoy C., Bayraktaroglu A.E., Karaali D. Predicting the intention to use a web‐based learning system: perceived content quality, anxiety, perceived system quality, image, and the technology acceptance model. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries. 2014;24(5):515–531. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim J. The platform business model and business ecosystem: quality management and revenue structures. Eur. Plann. Stud. 2016;24(12):2113–2132. [Google Scholar]