Abstract

Objective:

HIV-infected women (WLHIV) have >10-fold higher risk for squamous cell cancer of the anus (SCCA). Experts suggest cytology-based strategies developed for cervical cancer screening may prevent anal cancer by detecting anal histological High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (hHSIL) for treatment. Currently, there is no consensus on anal-hHSIL screening strategies for WLHIV.

Design:

Between 2014 and 2016, 276 WLHIV were recruited at 12 U.S. AIDS Malignancy Consortium (AMC) clinical-trials sites to evaluate hHSIL prevalence and (test) screening strategies.

Methods:

Participants completed detailed questionnaire, underwent anal assessments including high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) testing using hrHPV-HC2™ and hrHPV-APTIMA™, anal cytology, and concurrent high-resolution anoscopy. Screening test characteristics for predicting hHSIL validated by central pathology, were estimated: sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP), positive predictive value (PPV) and false-omission rate. Paired analyses compared SN and SP for hrHPV single tests to anal cytology alone.

Results:

83% (229/276) of enrolled WLHIV had complete anal assessment data and were included in this analysis. Mean age was 50, 62% black and 60(26%) had hHSIL. Anal cyotology (>ASC-US), hrHPV-HC2, and -APTIMA SN estimates were similarly high, (83%, 77%, and 75%, respectively, p-values>0·2). SP was higher for both hrHPV-APTIMA, and -HC2 compared with anal cytology (67% vs. 50%, p<0.001), and (61% vs. 50%, p=0·020), respectively.

Conclusion:

Anal hrHPV testing demonstrated similar SN for anal cytology (>ASC-US) to predict anal hHSIL. Among tests with similar SN, the SP was significantly higher for hrHPV-APTIMA and -HC2. Thus, anal hrHPV testing may be an important alternative strategy to anal cytology for anal hHSIL screening among WLHIV.

Keywords: Women living with HIV, Anal Dysplasia, Operating characteristics, High-Risk HPV test, Anal cytology, Screening

INTRODUCTION

Persons living with HIV (PLWH) are at elevated risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA) compared to the general population.1 Compared to the general population, men who have sex with men (MSM) living with HIV have the highest SCCA risk (nearly 30 to 40-fold) followed by women living with HIV (WLHIV) (nearly ten-fold higher risk).[1, 2] There are differences but also pathophysiological similarities between cervical and anal cancer, including an etiologic association withwith persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection that if persist can progress to precancerous lesions, known as high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL).[3] Because of high rates of SCCA among PLWH, several professional societies recommend algorithms similar to cervical cancer screening where anal cytology testing is followed by diagnostic high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) for anal HSIL detection and subsequent treatment to prevent progression to SCCA.[4]

The majority of prior studies have focused on determining the operating characteristics of anal cytology and high-risk (HR) HPV testing in population-based studies of HIV-positive MSM.[5] While the use of anal cytology has been widely accepted as the optimal screening modlaity for HIV-positive MSM for anal pre-cancers, the lack of studies measuring the performance characteristics for anal cancer screening among US WLHIV (i.e. cytology and/or HPV testing) hinders the ability to determine cost-effective screening strategies for these women.[6] Over the past two decades, HRHPV testing has been incorporated into cervical cancer prevention strategies in conjunction with cervical cytology to improve screening accuracy for the detection of cervical HSIL.[7] However, to the best of our knowledge, no prior work has evaluated clinical performance of anal HRHPV testing in lieu of, or in addition to anal cytology for anal cancer screening for anal HSIL in WLHIV.

An ongoing large randomized trial “ANal Cancer/HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR)” trial will address an important question regarding the efficacy of anal HSIL treatment for SCCA prevention for PLWH.[8] However, understanding clinical performance of screening strategies to detect anal HSIL among PLWH is crucial to develop efficient screening algorithms that will maximize cancer prevention and decrease unnecessary procedures. The AIDS Malignancy Consortium (AMC) study, “AMC-084: Screening HIV-positive women for anal cancer precursors (AMC084),” is a multi-center U.S.-based national trial[9] that was designed to determine the performance characteristics of anal cytology and HRHPV testing in WLHIV. As such, unlike prior studies, all enrolled women underwent screening evaluations including anal cytology, anal HPV tests and concurrent high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) and biopsy (in contrast to prior studies where biopsies were only conducted in women with abnormal cytology), thus minimizing the potenital for false negatives. In this paper, we describe the performance characteristics of anal cytology and anal HPV tests alone and in combination compared to HRA-guided biopsies at the baseline visit for the cohort of women enrolled in the national study (AMC 084).

METHODS

Study Design

AMC-084 is a longitudinal, multi-site national study of WLHIV to determine prevalence and incidence of anal HPV and hHSIL detected over a two-year follow-up period. WLHIV were recruited at twelve U.S. sites between 2014 and 2016. The clinicians responsible for performing HRA at each site were certified using a standardized approach focused on quality assessments developed and implemented by the AMC HPV Working Group.[9] The study protocol was approved by the U.S. National Cancer Institute, Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and by institutional review boards for each participating institution. Potential participants were screened using a standardized questionnaire and medical records review. At baseline, all women were evaluated using a standard protocol. Women without hHSIL were then followed-up semiannually for 2 years. Follow-up was and discontinued if incident anal hHSIL, the primary endpoint, was diagnosed.

Sample and Subjects

Eligible women were 18 years or older, living with HIV, had no history of anal HSIL by cytology or histology, and had laboratory test results within the past 120 days showing absolute neutrophil and platelet count of >750 cells/mm3 and ≥75,000 cells/mm3, respectively. Women with a history of pelvic radiation, anal or perianal cancer or treatment for anal or perianal condyloma or low-grade SIL (LSIL) within 4 months of study entry were ineligible.

Of 276 participants enrolled, 256 eligible participants had specimens available for central pathology review and comprised the baseline cohort. The cohort for evaluating test strategies consisted of the 229 study participants who had complete data on all tests: anal cytology and anal HPV results from both Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2, Qiagen, Inc, Valencia CA) and HPV-Aptima Test (Hologic Corp, San Diego, CA). Participant characteristics were summarized for the complete baseline cohort and compared with the test strategy cohort and were not significantly different (data not shown).

Procedures

Clinical charts were reviewed and study participants queried for HIV information (date of diagnosis, current and nadir CD4+ T-cell counts, current HIV viral load, and antiretroviral therapy history) and HPV-related information (past history of HPV-related anogenital diseases, including warts, abnormal cervical cytology and colposcopy results). A baseline questionnaire was administered to the study participants by research staff to determine smoking status and recent sexual history. HIV viral load and CD4 count data were collected within 120 days of study enrollment, and if not available from clinical chart review were subsequently collected. All participants underwent a targeted physical exam, including exams of the vulva, vagina/cervix, anus and perianus for signs of HPV-related lesions.

Anal specimen collection:

Two anal specimens were collected for cytology and HPV testing. The swab for cytology was immersed in the liquid-based cytology media required for local processing at each local institution (PreservCyt® or SurePath®). Because of concerns of the order of swab collection affecting the quality of the swab specimen on the analyses, anal swab specimens were collected from each study participant in the order as randomly assigned at the time of enrollment.

High-Resolution Anoscopy and Biopsy:

Following anal cytology/HPV specimen collection, a digital anorectal exam (DARE) was performed followed by HRA of the anal canal and perianus with at least 2 directed or random biopsies as previously described.[9]

Laboratory Testing

Cytology specimen processing:

Local pathology departments processed the cervical and anal cytology specimens and evaluated the cytology using the Bethesda Classification System.[10] Cytology samples did not undergo Central Pathology Review as all of these sites had prior quality assurance for anal cytology from other anal cancer prevention trials.

Anal HPV analyses:

Anal HPV-HC2 analysis were performed at the manufacturers’ laboratories (Qiagen Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD) as was HPV-Aptima (Hologic Inc., Marlborough, MA) and results were reported to the investigators. HPV-HC2 is a signal amplification assay that detects ≥1 picogram of HPV-DNA for a pool of 13 different high-risk HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68). HPV-Aptima assay is a nucleic acid amplification test that detects the HPV E6/E7 messenger RNA (mRNA) for a pool of 14 high-risk types of HPV (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68). HPV detection specimens underwent further analysis with the HPV-Aptima 16 18/45 Genotype Assay to identify specimens with HPV genotypes 16 and 18/45 (designated 16/18/45+).

Cytology specimen processing:

Local pathology departments processed the cervical and anal cytology specimens and evaluated the cytology using the Bethesda Classification System[10]. Specimens were evaluated as negative for intraepithelial lesions or malignancy (NILM), atypical squamous cells (ASC) of undetermined significance (ASC-US), ASC, cannot rule out high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H), and low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL and HSIL, respectively). Cytology samples did not undergo Central Pathology Review as all of these sites had prior quality assurance for anal cytology from other anal cancer prevention trials.

Anal histology:

The study outcome of interest was anal hHSIL (vs. less than hHSIL) as determined by the Central pathology consensus review; all biopsy histopathology slides were reviewed by at least 2 independent pathologist. If there was disagreement between the 2 pathologists, a third pathologist reivew served as a tie-breaker. Biopsy specimens were evaluated using terminology and classifications (including recommendations for p16 staining) from the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Project (LAST).[3] Anal histology was reviewed by local and central pathology as previously described.[9]

Statistical analysis

Log-linked binomial regression models were used to estimate risk ratios for anal HSIL detection. Models were adjusted for race, current CD4 count and history of anal sex as these variables were found to be significantly associated with hHSIL diagnosis in our previous study.[9] The Kappa statistic was computed to measure the agreement between tests. Proportions with exact binomial confidence intervals were computed for screening test characteristics, including sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP), positive predictive value (PPV), 1- negative predictive value (1-NPV) (also known as the False omission rate) for predicting hHSIL as determined by central pathology review as described above. McNemar’s chi-square test for paired categorical data was used to compare sensitivities and specificities for test strategies to cytology alone. The associations between swab collection order and HPV test results were evaluated using chi-square tests. P-values less than 0·05 were deemed statistically significant. Analyses were conducted in SAS/STAT software, Version 12·1 of the SAS System (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

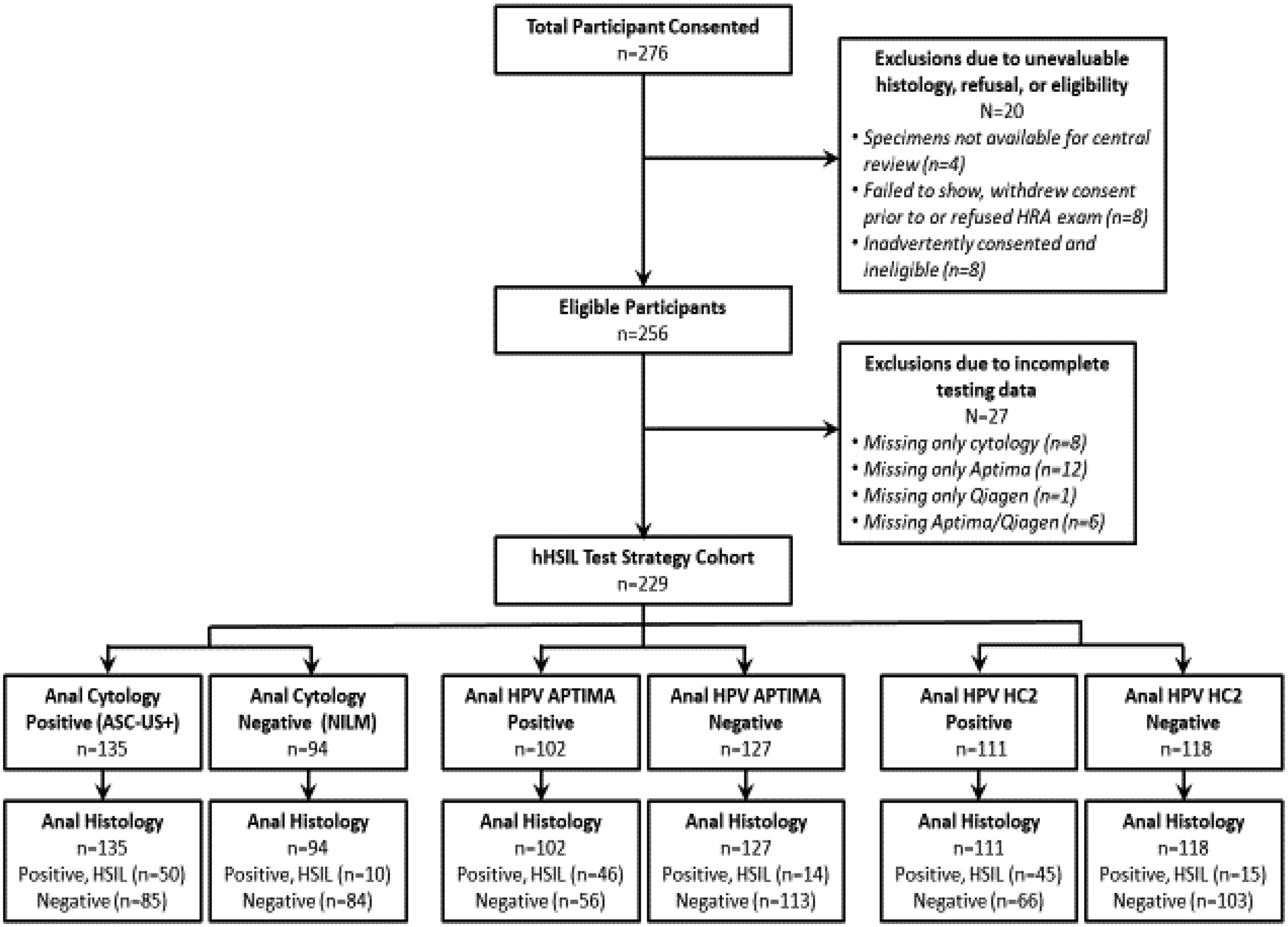

The derivation of the 229 women included in the test strategy cohort from the full baseline cohort (256 women) is shown in Figure 1. Enrollment occurred from February 2014 to June 2016. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of 229 women included in the test strategy cohort. The median age of WLHIV in the test strategy cohort was 50 years (IQR: 44–55). Women were predominantly non-Hispanic African Americans (62%), and current or former smokers (67%). Fifty-five percent reported at least one lifetime male anal sex partner, and nearly half (48%) reported a prior sexual assault. Most were on cART (96%) with relatively high CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts (median=667 [IQR: 455–878 cells/mm3]) and 86% had suppressed HIV viral load. Nearly 29% had abnormal cervical/vaginal cytology, with 27% testing positive for cervical/vaginal HPV-DNA.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram for Patient Test Strategy Cohort

Table 1: AMC084 – Screening Study.

Participant Characteristics1

| Demographic Characteristics | Test Strategy Cohort |

|---|---|

| N=2291 | |

| n (%) | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 50 (44–55) |

| Age | |

| <40 y | 29 (13) |

| 40–49 y | 74 (32) |

| ≥50 y | 126 (55) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| NH Black | 143 (62) |

| NH White or Other | 36 (16) |

| Hispanic | 50 (22) |

| Smoking Status | |

| Former/Current | 149 (67) |

| Never | 75 (33) |

| Education | |

| High school diploma or less | 120 (54) |

| Some college or higher | 101 (46) |

| Annual Income | |

| <$20K | 174 (82) |

| ≥$20K | 39 (18) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married/Not married, living with someone | 47 (21) |

| Divorced/Widowed/Single | 179 (79) |

| HIV Characteristics | |

| Current CD4 T-cell count, median (IQR) | 667 (455–878) |

| Range | 4–1961 |

| Current CD4 T-cell count | |

| ≤200 cells/mm3 | 16 (7) |

| 201–350 cells/mm3 | 21 (9) |

| >350 cells/mm3 | 192 (84) |

| Viral load | |

| Suppressed (≤200 copies/mm3) | 195 (86) |

| Unsuppressed (>200 copies/mm3) | 32 (14) |

| Nadir CD4 T-cell count | |

| ≤200 cells/mm3 | 110 (50) |

| >200 cells/mm3 | 111 (50) |

| Current cART User | |

| Yes | 216 (96) |

| No/unsure | 10 (4) |

| Reported Clinical History | |

| Lifetime Male Anal Sex Partners | |

| 0 | 99 (45) |

| 1 | 65 (30) |

| ≥2 | 55 (25) |

| History of Anogenital Warts | |

| Yes | 60 (27) |

| No | 161 (73) |

| History of Abnormal Cervical Cytology | |

| Yes | 123 (54) |

| No/unsure/declined | 103 (46) |

| History of Sexual Assault | |

| Yes | 106 (48) |

| No/declined | 115 (52) |

|

Baseline Cervical/vaginal Screening Results |

|

| Cervical /vaginal Cytology | |

| NILM2 | 158 (71) |

| ASC-US/LSIL | 56 (25) |

| ASC-H/HSIL | 10 (4) |

| Cervical /vaginal HPV (HC2) | |

| HPV+ | 62 (27) |

| HPV− | 166 (73) |

| Baseline Anal Screening Results | |

| Anal Cytology | |

| NILM3 | 94 (41) |

| ASCUS/LSIL | 114 (50) |

| ASC-H/HSIL | 21 (9) |

| Anal HPV APTIMA | |

| HPV+ | 102 (45) |

| HPV− | 127 (55) |

| Anal HPV HC2 | |

| HPV+ | 111 (48) |

| HPV− | 118 (52) |

| Baseline Anal Histology Outcome | |

| Anal Histology | |

| Benign | 133 (58) |

| LSIL | 36 (16) |

| HSIL | 60 (26) |

The denominators do not sum to 229 for some variables due to missing responses; variables with the most missing data are Annual Income (n=16), Lifetime Male Sex Partners (n=10), and Education (n=8).

No Intraepithelial Lesion or malignancy

There were a total of 60 prevalent hHSIL (26%) detected (Table 1). The prevalence of abnormal anal cytology (ASC-US+), and detection of anal HPV was high. The prevalence of ASC-US+ on anal cytology was 59%. ASC-H/HSIL were found in only 9% (21/229). Almost half tested positive by one or both anal hrHPV tests: 45% (102/229) were positive by HPV-Aptima, 48% (118/229) by HC2. HPV test and anal cytology results were unaffected by swab order (all p>0·25 for overall Wald test comparing three orderings, data not shown).

Tabular statistics and unadjusted risk ratios (RR) for anal HSIL by anal cytology, anal HPV testing, cervical cytology and cervical-HPV testing, adjusted for selected demographic and clinical variables are summarized in Table 2. Compared to women with NILM anal cytology, women with anal cytology of ASC-H or HSIL showed statistically significant increased risk of hHSIL as did those with anal ASC-US or LSIL but to a lesser extent (unadjusted RR=7·2 (95% CI: 3·8 to 13·5) and RR=2·8 (95% CI: 1·5 to 5·4), p<0·05, respectively). Cervical cytologic ASC-H or HSIL was strongly associated with anal hHSIL compared with normal cervical cytology (RR=3·1 (1·9 to 5·1) whereas cervical cytology of LSIL or ASC-US was not (RR=1·3 (95% CI: 0·8 to 2·2)). Testing positive for HPV in the anus or cervix were all associated with anal hHSIL: anal HPV by HC2 (RR=3·6, 95% CI: 1·9 to 5·4), anal HPV by HPV-Aptima (RR=4.1, 95% CI: 2·4 to 7·0), or cervical HPV by HC2 (RR=1·7, 95% CI: 1·1 to 2·6). In the multivariable model, which adjusted for race, current CD4, and history of anal sex, abnormal anal cytology, detection of anal HPV, ASC-H/HSIL cervical cytology, and detection of cervical HPV by HC2 were still associated with anal hHSIL.

Table 2:

Positivity for Individual Anal and Cervical Screening Tests according to Anal HSIL Histology in the Test Strategy Cohort

| Total | Anal hHSIL | Unadjusted RR | Adjusted RR1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anal Cytology | N | n (%) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) |

| NILM | 94 | 10 (11) | 1 | 1 |

| ASC-US+ | 135 | 50 (37) | 3·48 (1·86, 6·51) | 3·35 (1·65, 6·82) |

| ASCUS/LSIL | 114 | 34 (30) | 2·80 (1·46, 5·37) | 1·49 (1·06, 2·08) |

| ASC-H/HSIL | 21 | 16 (76) | 7·16 (3·80, 13·49) | 2·33 (1·58, 3·43) |

| Anal HPV APTIMA | ||||

| Negative | 127 | 14 (11) | 1 | 1 |

| Positive for any HRHPV | 102 | 46 (45) | 4·09 (2·39, 7·01) | 2·02 (1·35, 3·02) |

| HPV+, 16/18/45− | 55 | 17 (31) | 2·80 (1·49, 5·28) | 3·17 (1·63, 6·17) |

| 16/18/45+ | 47 | 29 (62) | 5·60 (3·25, 9·63) | 5·75 (3·15, 10·50) |

| Anal HPV HC2 | ||||

| Negative | 118 | 15 (13) | 1 | 1 |

| Positive | 111 | 45 (41) | 3·55 (1·89, 5·38) | 1·77 (1·23, 2·54) |

| Cervical Cytology 2 | ||||

| NILM | 158 | 36 (23) | 1 | 1 |

| ASC-US/LSIL | 56 | 17 (30) | 1·33 (0·82, 2·17) | 1·29 (0·74, 2·23) |

| ASC-H/HSIL | 10 | 7 (70) | 3·07 (1·87, 5·05) | 3·41 (2·04, 5·69) |

| Cervical HPV HC2 2 | ||||

| Negative | 166 | 36 (22) | 1 | 1 |

| Positive | 62 | 23 (37) | 1·71 (1·11, 2·64) | 1·84 (1·15, 2·95) |

| Total | 229 | 60 (26) |

RR=Risk Ratio, CI=Confidence Interval

Adjusting for race (Non-Hispanic black vs. all others), current CD4 (≤200, 201–350, >350), and history of anal sex (0 vs. 1+ partners). 10 women were missing data for at least one of these covariates so that the adjusted models included at most 219 women.

Five women had missing data for cervical cytology and one for cervical HPV testing

Test Performance Characteristics: Sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP) and predictive value of positive predictive value (PPV) and false omission rate (1-NPV) tests

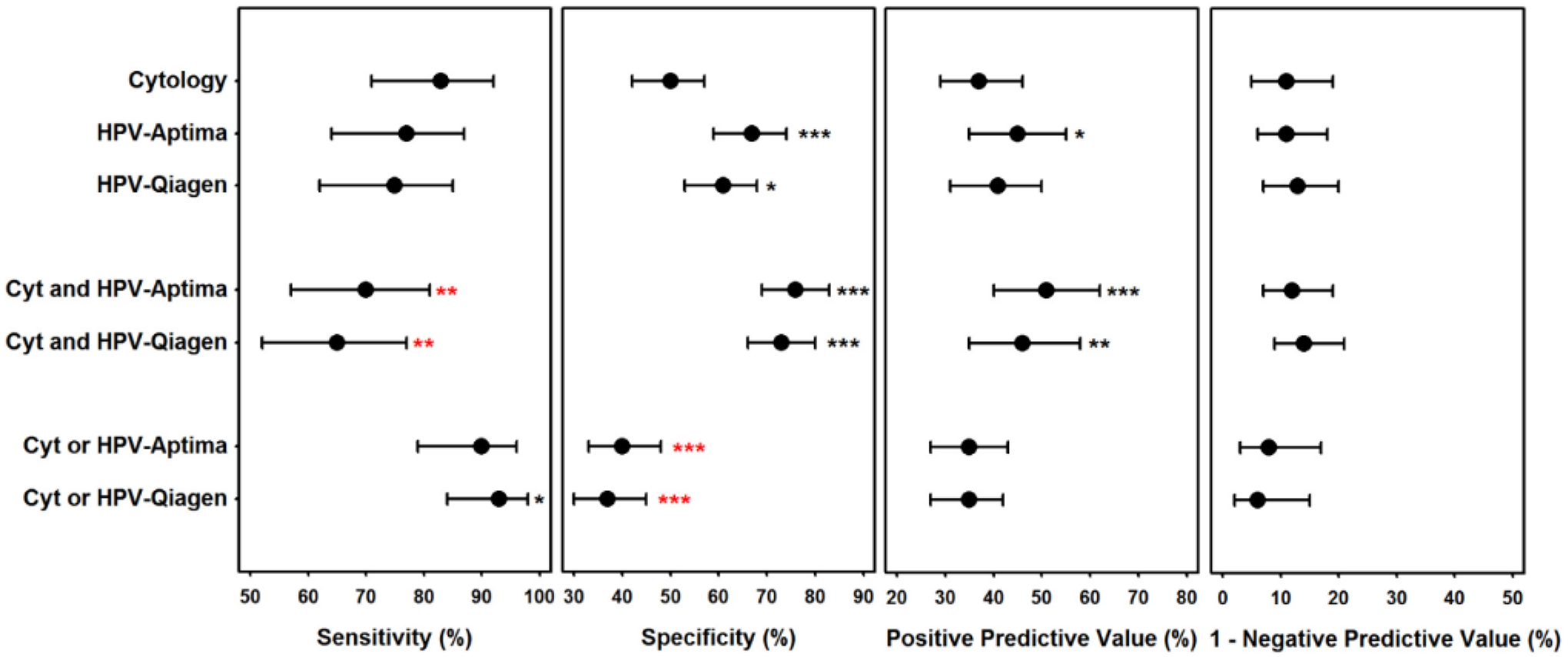

Figure 2 and Table 3 compare the operating characteristics of cytology to 8 alternate screening strategies for a referral to HRA and anal HSIL detection. The SN for abnormal (ASC-US+) cytology was 83% and was not statistically significantly higher than SN for detection of anal HPV-Aptima (HPV- Aptima+) and HPV-HC2+ (77% and 75% respectively); 1-NPV for anal hHSIL were low for these tests and comparisons to cytology were all non-significant (all p>0.30). While the SP for ASC-US+ cytology was 50%, the SP for HPV- Aptima+ was 67% (p< 0·001) and HPV-HC2+ was 61% (p=0·020) demonstrating that the specificity of both HRHPV tests were significantly higher than cytology. The PPV for HPV- Aptima+ was significantly higher than PPV for ASC-US+ anal cytology (45% versus 37%, p=0·011), but PPV (41%) for HPV-HC2+ was not (p=0·27). Anal cytology of ASC-H/HSIL showed the highest SP (97%) but the lowest SN (27%) compared with other screening tests (all p<0.001). Aptima 16/18/45+ had the second highest SP (89%, 95% CI 84%, 94%) but also the second lowest SN (43%, 95% CI 35%, 62%). Abnormal cytology (ASC-US+) compared with either HPV+ test had higher rates of referrals for HRA (59% vs. 45–48%) and higher number referred per hHSIL identified (2·3 vs. 1·7–1·8) (Table 3).

Figure 2:

Test Characteristics for Performance of Cytology, HPV-Aptima, and HPV-Qiagen for Predicting hHSIL in 229 WLHIV.

Paired comparisons to corresponding cytology test characteristic p-value: * 0.01–0.05, ** 0.001-<0.01, *** <0.001; red indicates significantly worse than cytology. Dot represent test characteristic estimate and error bars represent exact binomial confidence intervals.

Table 3:

Operating Test Characteristics for Anal Cancer Screening Test Strategies for Predicting Anal Histological HSIL (hHSIL) in 29 WLHIV

| Anal Testing screening Strategies | Positive Test (HRA Referral) | Number referred per hHSIL identified* | Youden’s J1 | SENS (95% CI) | SPEC (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | 1-NPV2 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single test | |||||||

| Cytology (ASC-US+) | 135 (59%) | 2.3 | 0·33 | 83% (71%, 92%) | 50% (42%, 57%) | 37% (29%, 46%) | 11% (5%, 19%) |

| Cytology (LSIL+) | 66 (29%) | 1.1 | 0·40 | 58% (45%, 71%) | 82% (75%, 87%) | 53% (40%, 65%) | 15% (10%, 22%) |

| Cytology (ASC-H/HSIL) | 21 (9%) | 0.3 | 0·24 | 27% (16%, 40%) | 97% (93%, 99%) | 76% (53%, 92%) | 21% (16%, 27%) |

| APTIMA (positive any type) | 102 (45%) | 1.7 | 0·44 | 77% (64%, 87%) | 67% (59%, 74%) | 45% (35%, 55%) | 11% (6%, 18%) |

| APTIMA 16/18/45+ | 47 (21%) | 0.8 | 0·37 | 48% (35%, 62%) | 89% (84%, 94%) | 62% (46%, 75%) | 17% (12%, 23%) |

| HC2 | 111 (48%) | 1.8 | 0·36 | 75% (62%, 85%) | 61% (53%, 68%) | 41% (31%, 50%) | 13% (7%, 20%) |

| Triage (Both screening tests positive) | |||||||

| ASC-US+ Cytology and APTIMA | 82 (36%) | 1.4 | 0·46 | 70% (57%, 81%) | 76% (69%, 83%) | 51% (40%, 62%) | 12% (7%, 19%) |

| ASC-US+ Cytology and HC2 | 84 (37%) | 1.4 | 0·38 | 65% (52%, 77%) | 73% (66%, 80%) | 46% (35%, 58%) | 14% (9%, 21%) |

| (ASC-US and APTIMA+) OR LSIL+ | 100 (44%) | 1.7 | 0·42 | 75% (62%, 85%) | 67% (60%, 74%) | 45% (35%, 55%) | 12% (7%, 18%) |

| (ASC-US/LSIL and APTIMA+) OR ASC-H+ | 85 (37%) | 1.4 | 0·45 | 70% (57%, 81%) | 75% (67%, 81%) | 49% (38%, 60%) | 13% (8%, 19%) |

| ASC-US+ and APIMA 16/18/45+ | 38 (17%) | 0.7 | 0·36 | 43% (31%, 57%) | 93% (88%, 96%) | 68% (51%, 83%) | 18% (13%, 24%) |

| APTIMA and HC2 | 91 (40%) | 1.5 | 0·41 | 70% (57%, 81%) | 71% (64%, 78%) | 46% (36%, 57%) | 13% (8%, 20%) |

| Co-testing (One or more positive screening tests) | |||||||

| ASC-US+ Cytology or APTIMA | 155 (68%) | 2.6 | 0·30 | 90% (79%, 96%) | 40% (33%, 48%) | 35% (27%, 43%) | 8% (3%, 17%) |

| ASC-US+ Cytology or HC2 | 162 (71%) | 2.7 | 0·30 | 93% (84%, 98%) | 37% (30%, 45%) | 35% (27%, 42%) | 6% (2%, 15%) |

| HC2 or APTIMA | 122 (53%) | 2.0 | 0·39 | 82% (70%, 90%) | 57% (49%, 64%) | 40% (31%, 49%) | 10% (5%, 18%) |

SENS=Sensitivity, SPEC=Specificity, PPV=Positive Predictive Value, NPV=Negative Predictive Value;

SENS+SPEC-1;

1-NPV, or false omission rate

Figure 2 and Table 3 also show triage (or in series) and co-testing strategies (or in-parallel strategies) operating characteristics for referral for HRA for the detection of anal HSIL. Triage screening strategies that combine ASC-US+ anal cytology with the detection of HRHPV demonstrated that the SN of cytology ASC-US+ as well as HC2+ was 65% and that of cytology ASC-US+ as well as HPV- Aptima + was 70%; both of these triage strategies were less sensitive than cytology ASC-US+ alone (p<0.01, for both). Accordingly, the SPs of both triage strategies were significantly higher than cytology alone; 73% for ASC-US+ as well as HC2+ and 76% for ASC-US+ as well as HPV- Aptima + (p<0.001 for both). Co-testing where positivity on either screening test (cytology ASC-US+or detection of HRHPV) showed that having abnormal cytology ASC-US+ or testing HPV-HC2+ was more sensitive (93%) than ASC-US+cytology alone (p=0.03), whereas the SN of abnormal cytology or HPV- Aptima + (90%) was not (p-value>0.1). The SP of co-testing strategies significantly worse than cytology; 37% for both ASC-US+ and HC2+ and 40% for both ASC-US+ and HPV-Aptima + (p<0.001 for both).f. We also assessed if detection of HRHPV helped to triage minimally abnormal anal cytology (ASC-US, cLSIL) for HRA referral for the detection of anal hHSIL. Of women with cASC-US, 15/69 (22%) had underlying hHSIL, 34/69 (49%) of the ASC-US were HPV+, and 10/15 (67%) with hHSIL were both HPV+ with cASC-US. Of women with cLSIL, 19/45 (42%) had underlying hHSIL, 30/45 (67%) were HPV+, and 16/19 (84%) with hHSIL were both HPV+ and cLSIL (data not shown).

Screening Test Agreement

The test agreement of anal HPV detection with HPV- Aptima and HC2 was high (Kappa=0·73 [0·64–0·82]). However, the test agreement of cytology (ASC-US+) and HPV- Aptima (Kappa=0·37 [0·26–0·49]) and HPV-HC2 (Kappa=0·32 [0·20–0·44]) agreement was poor (data not shown).

Age-Stratified Analyses

In addition, age-stratified tabular analyses for these screening tests (individually and in combination) to predict hHSIL in WLHIV did not show differences between participants <45 years of age in comparison to those ≥45 but some comparisons were limited by small sample size, particularly for sensitivity. (Supplementary Table 1)

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to compare the operating test characteristics for anal cytology and commercially available HPV assessments for the detection of anal hHSIL among WLHIV. In our cohort of 229 women, the majority (59%) had abnormal anal cytology (≥ASC-US) and fewer than 50% had anal HPV detected (HPV-Aptima 45% and HC2 48%). We found that abnormal anal cytology (ASC-US+) had similar sensitivity but lower specificity for the detection of anal hHSIL compared with either anal HPV test (HPV-Aptima or HC2) alone. We also evaluated combinations of the testing modalities, and of these testing modalities, and anal HPV testing (with either HPV-Aptima or HC2) alone demonstrated optimal screening characteristics. Our study provides evidence that the specificity of anal HRHPV testing is higher than anal cytology and, unlike screening for hHSIL in MSM living with HIV for whom anal HRHPV testing has poor test characteristics (low SP, high false positive rate) due to the high prevalence of HRHPV infection in that popuation, anal HRHPV testing alone appears to be more appropriate for screening WLHIV for hHSIL.

Currently, several professional societies, as well as the New York State HIV guidelines recommend screening PLWH for anal cancer precursors using anal cytology. Of note, cervical cancer screening guidelines have incorporated HRHPV testing as an adjunct to cytology and in many countries HRHPV testing is now the primary screening test for cervical cancer.[11] Anal HRHPV detection has not been proposed as a viable screening option for MSM living with HIV because of high rates of prevalent HRHPV infection.[12] Recent meta-analyses of MSM living with HIV demonstrated that pooled SN and SP for anal cytology was 81–82% and 45–54·0%, respectively, and anal HRHPV testing had SN and SP of 91–95% and 24–27%,[13, 14] thus, making the specificity of HRHPV testing too poor to use in this population. Our findings demonstrating similar SN but improved SP for HRHPV compared with anal cytology for detection of anal HSIL in WLHIV differs from these prior reports in MSM living with HIV andis likely due to the lower prevalence of HRHPV infection in WLHIV.

WLHIV have an increased incidence rate of anal cancer compared to women without HIV (Standardized Incidence Ratio [SIR] of 7·9–13·5).[1] However, the risk is lower compared with MSM living with HIV(adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio of 0.3). WLHIV appear have similar anal HSIL prevalence compared to MSM living with HIV (27% (95%CI, 22%−33%)9 vs. 29% (95% CI 18–39)[12] but rates of anal HRHPV detection are substantially lower than those reported in MSM living with HIV (50% [95% CI: 16%−85%][15, 16] vs 73·5 [95%CI: 64–89])[12] respectively. Lesion size, infection with multiple HPV types, and anatomic differences have been hypothesized to cause SN and SP differences. Thus, given the differences in the prevalence of anal HSIL and anal HRHPV infection between WLHIV and MSM living with and without HIV, specific screening recommendations focused on HR HPV screening for WLHIV may be appropriate.

Interestingly, unlike studies evaluating screening tests for cervical HSIL, our study did not show improved SN for anal hHSIL detection using HRHPV testing compared to cytology. One large meta-analysis conducted by Cochrane found that among 40 studies evaluating multiple methodologies for the detection of cervical hHSIL, the pooled sensitivity estimates for HRHPV hybrid capture 2 (HC2) (1 pg/mL threshold) versus conventional cytology (CC) ASC-US+ or liquid-based cytology (LBC-ASC-US+) were 89.9%, 62.5% and 72.9%, respectively, and pooled specificity estimates were 89.9%, 96.6%, and 90.3%, respectively.[17] The differences in test performance between cervical and anal screening tests may be due to differences in the anatomic site, including differences in visual interpretation of cytologic findings based on expertise, and differences in test protocols and diagnostic thresholds between cervical and anal HR HPV specimens. Further research is necessary to determine if anal-specific protocols may improve the sensitivity for cytologic interpretations as well as HR HPV testing protocols.

In particular, HRHPV types 16 (and to a lesser extent 18) have been shown to correlate with progression to anal cancer.[18] Although HR HPV types have been detected in 100% of cervical cancers and 88% of anal cancers, HPV types 16 or 18 in particular are associated with 70% of cervical and 80% of anal cancers. [19] Furthermore, recent studies suggest that HPV 16 primarily drives the progression from aHSIL to cancer (except in HIV-positive individuals where rates of other HR HPV types are commonly detected in invasive anal cancer specimens). [18] Indeed, in our study, we found that Aptima 16,18 or 45 had the second highest specificity (89%) and PPV (62%). Although Aptima 16/18/45 alone has high specificities and positive predictive values, the low sensitivity and higher false omission rates of the test make it a less optimal screening test for anal hHSIL.

We did not find any difference in test performance characteristics by age. This contrasts with Jin et al[20] who found that the specificity of anal cytology improved with older age. They hypothesize that younger men may have more transient HRHPV and low grade lesions, thus decreasing the specificity for this population. In WLHIV, transient anal HRHPV infections may be less frequent. We have previously shown that the prevalence of anal hHSIL in our cohort did not change by age.[9]

The strengths of this study include the racial and ethnic diversity of the participants and that all women enrolled in the study underwent high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) and biopsy (not only women with abnormal cytology). Furthermore, all the clinicians who performed HRAs underwent a rigorous certification process before study sites were activated. Our study is also different than other prior anal screening in that prior studies have either used referral populations (ie conducting HRA and biopsy only among women with ASC-US or greater anal cytology), or did not perform at least 2 anal biopsies from each patient, even if the HRA appeared negative. The limitations of the study include: no central review of all the local cytology interpretations, and the specimens for cytology and HRHPV specimens were collected in separate specimen containers. However, the order of the specimen collection was randomly assigned to decreased any potential bias from fewer cells collected at the second specimen collection). Finally, the age range of the participants did not include many women under the age of 30, thus our power to detect the difference in screening test characteristics for that age group may be limited.

In conclusion, HC-2 and HPV-Aptima anal HRHPV screening tests were found to have similar sensitivity and improved specificity compared to liquid-based anal cytology, for the detection of anal HSIL in this multi-center cohort study of WLHIV. Because the risk of any anal HSIL progression to invasive anal cancer is unknown, and not all anal HSIL will progress to invasive cancer, there may not be any differential cancer risk for aHSIL detected by the different screening strategies proposed. However, given the costs to patients and health care as well as the limited access to HRA, and the prolonged natural history of progression from anal HSIL to invasive anal cancer, the value of non-cytology based tests, such as HPV biomarkers as the primary screening test could improve screening for anal HSIL in WLHIV and should be further investigated as part of anal screening programs for this population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

EC, JL, EAS, AAD planned the study, EC, SYL, DJL, EAS wrote the manuscript, MHE,NJ, JMBL, JMP, TW, LFB, RFC, RL, HMG, ALF, and SEG did acquisition of data, SYL, DJW, JL designed the analysis, SYL analysed the data, EC, EAS, AAD, DJW, ALF, DC, MKR interpreted the data, all authors read and approved the final manuscript, and NP, JMP and PP critically revised the paper.

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Zenab Yusuf for helping with editorial and manuscript submission assistance.

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, CA163103 to EYC and EAS (PI: Dr. Elizabeth Y Chiao) and UM1CA121947 to EYC, SML, EAS and AIDS Malignancy Consortium sites (PI: Dr. Ronald Mitsuyasu). Qiagen, Hologic and HPV-Aptima provided in-kind contributions for HPV testing.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST AND SOURCE OF FUNDING

Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, CA163103 to EYC and EAS (PI: Dr. Elizabeth Y Chiao) and UM1CA121947 to EYC, SML, EAS and AIDS Malignancy Consortium sites (PI: Dr. Ronald Mitsuyasu). Hologic and HPV-Aptima provided in-kind contributions for HPV testing.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The submitted COIs detail the various grants, fees as well as non-financial support that any of the authors have received during the course the study. A brief overview of the details captured in the COIs is presented here. Drs. Citron, Katayoon, Barroso, Guiot, Jay, Lensing, Levine, French and Chiao do not have anything to disclose other than funding from the NIH, and don’t report any conflict of interest. Dr. Goldstone received personal fees from Merck and Co, grants and other form of payments Medtronic Inc, grants from Antiva, Inovio and other support from THD America. Dr. Darragh reports non-financial support from Hologic and personal fees from Roche, BD, Antiva and TheVax. Dr. Einstein has advised or participated in educational speaking activities but does not receive an honorarium from any companies. In specific cases, his employers have received payment for his time spent for these activities from Papivax, Cynvec, Altum Pharma, Photocure, Becton Dickenson, and PDS Biotechnologies. Rutgers has received grant funding for research-related costs of clinical trials that Dr. Einstein has been the overall or local PI within the past 12 months from J&J, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Advaxis, and Inovio. Dr. Einstein also reports other support from Photocure, Papivax, Cynvec, PDS, Altum Pharma and Becton Dickinson, outside the submitted work. Dr. Stier reports non-financial support from Qiagen and Hologic, Inc. Dr. Berry-Lawhorn reports personal fees from ANTIVA and Dr. Deshmukh reports personal fees from Merck Inc. Dr. Palefsky received grants and non-financial support from Merck and Co. He also received grants, personal fees and other support from Vir Biotechnologies, Ubiome and Antiva Biosciences. He received personal fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novan, Vaccitech, and non-financial support from Virion Therapeutics. Dr. Dorothy Wiley reports grants from National Cancer Institute, during the conduct of the study and is a Merck & Co., Inc. (Merck, Sharp & Dohme [MSD]): Speakers Bureau member. Dr. Wilkin reports grants and personal fees from GlaxoSMithKline/ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colon-Lopez V, Shiels MS, Machin M, Ortiz AP, Strickler H, Castle PE, et al. Anal Cancer Risk Among People With HIV Infection in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(1):68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Achenbach CJ, Jing Y, Althoff KN, D’Souza G, et al. Cumulative Incidence of Cancer Among Persons With HIV in North America: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163(7):507–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, Heller DS, Henry MR, Luff RD, et al. The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization Project for HPV-Associated Lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136(10):1266–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang CJ, Palefsky JM. HPV-Associated Anal Cancer in the HIV/AIDS Patient. Cancer Treat Res 2019; 177:183–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin F, Roberts JM, Grulich AE, Poynten IM, Machalek DA, Cornall A, et al. The performance of human papillomavirus biomarkers in predicting anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in gay and bisexual men. AIDS 2017; 31(9):1303–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazenby GB, Unal ER, Andrews AL, Simpson K. A cost-effectiveness analysis of anal cancer screening in HIV-positive women. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2012; 16(3):275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AIDSinfo. Human Papillomavirus | Adut and Adolescent Opportunistic Infection. In.

- 8.Institute NC. Anchor Trial Launch-National Cancer Institute. In.

- 9.Stier EA, Lensing SY, Darragh TM, Deshmukh AA, Einstein MH, Palefsky JM, et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Anal High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions in Women Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70(8):1701–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O’Connor D, Prey M, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA 2002; 287(16):2114–2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lees BF, Erickson BK, Huh WK. Cervical cancer screening: evidence behind the guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 214(4):438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machalek DA, Poynten M, Jin F, Fairley CK, Farnsworth A, Garland SM, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13(5):487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke MA, Wentzensen N. Strategies for screening and early detection of anal cancers: A narrative and systematic review and meta-analysis of cytology, HPV testing, and other biomarkers. Cancer Cytopathol 2018; 126(7):447–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goncalves JCN, Macedo ACL, Madeira K, Bavaresco DV, Dondossola ER, Grande AJ, et al. Accuracy of Anal Cytology for Diagnostic of Precursor Lesions of Anal Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2019; 62(1):112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Pokomandy A, Kaufman E, de Castro C, Mayrand MH, Burchell AN, Klein M, et al. The EVVA Cohort Study: Anal and Cervical Type-Specific Human Papillomavirus Prevalence, Persistence, and Cytologic Findings in Women Living With HIV. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(4):447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stier EA, Sebring MC, Mendez AE, Ba FS, Trimble DD, Chiao EY. Prevalence of anal human papillomavirus infection and anal HPV-related disorders in women: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 213(3):278–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koliopoulos G, Nyaga VN, Santesso N, Bryant A, Martin-Hirsch PP, Mustafa RA, et al. Cytology versus HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in the general population. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 8:CD008587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albuquerque A, Stirrup O, Nathan M, Clifford GM. Burden of anal squamous cell carcinoma, squamous intraepithelial lesions and HPV16 infection in solid organ transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Martel C, Plummer M, Vignat J, Franceschi S. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int J Cancer 2017; 141(4):664–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin F, Grulich AE, Poynten IM, Hillman RJ, Templeton DJ, Law CL, et al. The performance of anal cytology as a screening test for anal HSILs in homosexual men. Cancer Cytopathol 2016; 124(6):415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.