Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) remains a treatment option for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who fail to respond to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). While imatinib seems to have no adverse impact on outcomes after transplant, little is known on the effects of prior use of second-generation TKI (2GTKI). We present the results of a prospective non-interventional study performed by the EBMT on 383 consecutive CML patients previously treated with dasatinib or nilotinib undergoing allo-HCT from 2009 to 2013. The median age was 45 years (18–68). Disease status at transplant was CP1 in 139 patients (38%), AP or >CP1 in 163 (45%), and BC in 59 (16%). The choice of 2GTKI was: 40% dasatinib, 17% nilotinib, and 43% a sequential treatment of dasatinib and nilotinib with or without bosutinib/ponatinib. With a median follow-up of 37 months (1–77), 8% of patients developed either primary or secondary graft failure, 34% acute and 60% chronic GvHD. There were no differences in post-transplant complications between the three different 2GTKI subgroups. Non-relapse mortality was 18% and 24% at 12 months and at 5 years, respectively. Relapse incidence was 36%, overall survival 56% and relapse-free survival 40% at 5 years. No differences in post-transplant outcomes were found between the three different 2GTKI subgroups. This prospective study demonstrates the feasibility of allo-HCT in patients previously treated with 2GTKI with a post-transplant complications rate comparable to that of TKI-naive or imatinib-treated patients.

Subject terms: Medical research, Chronic myeloid leukaemia

Introduction

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are established as standard-of-care therapy for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) since the advent of the first TKI, imatinib mesylate, in the late 1990s [1] and the results of IRIS trial that fundamentally revolutionized the management of the disease [2]. Later, the second-generation TKIs (2GTKIs)—particularly dasatinib and nilotinib—have shown extremely encouraging results in the setting of imatinib resistance or intolerance with long-term overall survival (OS) estimated at >70% [3, 4], while in newly diagnosed CML the 5-year cumulative probability for achieving major molecular response is >75%, significantly higher than with imatinib [5, 6]. However, the use of a third-line 2GTKI (switching between dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib) may be of limited benefit with usually not durable responses [7] especially for the patients with primary cytogenetic resistance [8]. Furthermore, the remarkable efficacy of the third-generation TKI, ponatinib, is highly tempered by a significant vascular toxicity [9]. Finally, 15% of the initial CML population will require an alternative treatment [10]. Thus, despite the efficacy of TKIs, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) remains an effective and potentially curative option [11–13] for patients who fail to respond durably to TKIs or for patients presented with advanced stage disease.

While the use of imatinib seems to have no adverse impact on outcomes after transplant as shown in early studies [14–18], it is still uncertain whether prior use of 2GTKI affects post-transplantation outcomes. Selection of more aggressive or resistant clones could be expected. Furthermore, suboptimal outcomes could result from increased direct drug toxicity [19] or immune dysfunction [20, 21] given the fact that each TKI has multiple off-targets effects. Previous studies [22–26] provided no evidence of detrimental effect of prior allo-HCT 2GTKIs, but they are mainly retrospective analyses with small number of patients. Moreover, they did not address the question of whether dasatinib compared to nilotinib or to the combination of both has a different impact on subsequent allo-HCT. In order to address these issues we conducted a multicenter prospective non-interventional study on behalf of Chronic Malignancy Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT).

Patients, materials, and methods

We prospectively registered adult patients with a diagnosis of CML (all phases) who underwent first allo-HCT between December 2009 and September 2013 and had been previously treated with dasatinib or nilotinib regardless of their response to these drugs. A specific data collection form was sent to the transplant centers to capture the relevant information at the appropriate intervals (day +100; 1 year; 2 years after transplant). The data on the prior treatment of patients with 2GTKI were collected retrospectively as part of the medical history. Informed consent to authorize the release of medical information to the EBMT was obtained in all patients in accordance with the principles laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. A total of 446 patients were registered for participation, but 63 (14.1%) patients were excluded from the study due to unconfirmed eligibility. Finally, 383 patients from 93 EBMT centers in 27 countries were included in the analysis.

Study endpoints

The primary objective of our study was to evaluate the influence of prior treatment with 2GTKIs in CML patients on engraftment rates and non-relapse mortality (NRM) after allo-HCT. The secondary objectives were to evaluate the effect of 2GTKIs on transplantation-related toxicity—mainly incidence and severity of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) and hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS)—overall and disease-free survival and the relapse rate.

Definitions

Disease status at the start of 2GTKI treatment and at transplant (last disease assessment prior to transplant) was defined according to European LeukemiaNet [11]. More precisely, all patients beyond first chronic phase (>CP1) prior to transplant were patients who had developed blast crisis (BC) beforehand and regained a chronic phase stage after treatment. Patients in accelerated phase (AP) remained in AP regardless of their response to treatment as CP2 can only be achieved after developing BC but not after AP.

The date of engraftment was defined as the first of 3 consecutive days where the absolute neutrophil count was ≥500/μL. Relapse was defined as hematologic relapse in case of previous remission, or progression in case of previous AP or BC. NRM was defined as death without prior relapse or progression. OS was defined as time from transplant to death from any cause, or to last follow-up if alive. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as time from transplant to relapse or progression or to death from any cause. GvHD cases were divided into acute and chronic ones based on the time of onset using a cutoff of 100 days as previously described [27, 28]. EBMT score was calculated according to Gratwohl et al. [29].

Statistical analysis

Standard non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney, Kruskall–Wallis, χ2, or Fisher exact) were used to compare characteristics between groups. Probabilities of OS and RFS were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared between the 2GTKIs groups by the log-rank test. Endpoints with competing risks (engraftment, relapse, acute and chronic GvHD, and NRM) were evaluated by cumulative incidence curves and compared between the 2GTKIs groups by Gray’s test. Adjusted analyses were done applying the Cox regression for the (cause-specific) hazards of event. The following variables were initially assessed and considered candidates for the multivariable model if significant at 0.2 level in the univariate analysis: pre-transplantation TKI use, calendar year of transplant, patient’s gender, patient’s age at transplantation, disease status at start of 2GTKI and at transplantation, interval between diagnosis and transplantation, type of donor, donor–recipient gender combination, donor–recipient CMV constellation, graft source, T-cell depletion, intensity of conditioning regimen (RIC vs MAC), TBI given, performance status at transplant, and EBMT risk score. The reported models were checked to be robust with respect to the consideration of a potential center effect and the proportional hazards assumption.

Results

The 2GTKI used prior allo-HCT was dasatinib for 155 patients (40%), nilotinib for 64 patients (17%), whereas 164 patients (43%) had a sequential treatment of dasatinib and nilotinib with or without bosutinib/ponatinib. Only 5/164 patients of this third group had bosutinib, while 8/164 patients had ponatinib. The majority of patients (306/383, 80%), had imatinib as primary treatment at diagnosis and therefore switched to 2GTKI at a later stage. The median follow-up period after transplantation was 37 months (1–77). Of note, the median follow-up for the dasatinib group was longer (44 months, range 1–77) compared to the nilotinib (36 months, range 3–62) and the combination groups (34 months, range 1–71) showing that dasatinib was the preferred 2GTKI in the earlier years of the study.

Patient characteristics

The patient characteristics for all patients and the three 2GTKI subgroups are shown in Table 1. The median age was 45 years (18–68). Disease status at the start of 2GTKI treatment was reported for 265 patients: 123 patients (46%) were in first chronic phase (CP1), 67 patients (25%) were in AP or >CP1, and 75 patients (28%) were in BC. Overall disease status at allo-HCT was CP1 in 139 patients (38%), AP or >CP1 in 163 (45%), and BC in 59 (16%). Of note, only 29% of patients who received dasatinib were in CP1 at the start of 2GTKI treatment and at the time of SCT compared with 45% at the start of 2GTKI and 40% at transplant for patients treated with nilotinib. (Supplementary data: cross tables of disease stage at diagnosis vs disease stage at 2GTKI vs disease stage at transplant). The median interval from diagnosis to allo-HCT was 22 months (2–267) and the median interval between starting 2GTKI and allo-HCT (duration of 2GTKI) was 10 months (1–191). The donor was an HLA-identical sibling in 130 cases (35%). Allo-HCT was performed using peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) in 77% of cases, while 71% of the conditioning regimens were myeloablative. The EBMT score was low (0–2) in 26 (7%), intermediate (3–4) in 216 (62%), and high (5–7) in 107 patients (31%). Of note, the median EBMT score was 4 for each of the three 2GTKI groups. χ2 test showed that only interval between diagnosis and transplantation and disease status at start of 2GTKI and at transplant had significantly different distribution according to the 2GTKI group.

Table 1.

Patient, disease, and transplantation characteristics.

| All patients | Dasatinib | Nilotinib | Sequential/other | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n eval | n (%) | n eval | n (%) | n eval | n (%) | n eval | n (%) | P |

| No. of patients | 383 | 155 | 64 | 164 | |||||

| Age, years, median (range) | 383 | 45 (18–68) | 155 | 45 (18–68) | 64 | 49 (21–67) | 164 | 45 (18–67) | 0.46 |

| Male sex | 383 | 251 (65) | 155 | 110 (71) | 64 | 37 (58) | 164 | 104 (63) | 0.33 |

| Karnofsky score at SCT | 357 | 143 | 60 | 154 | 0.07 | ||||

| >80% | 271 (76) | 100 (70) | 50 (83) | 121 (79) | |||||

| ≤80% | 86 (24) | 43 (30) | 10 (17) | 33 (21) | |||||

| Time from diagnosis to allo-HCT | 383 | 155 | 64 | 164 | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤12 months | 93 (24) | 55 (35) | 15 (23) | 23 (14) | |||||

| >12 months | 290 (76) | 100 (65) | 69 (77) | 141 (86) | |||||

| Disease stage at 2GTKI | 265 | 108 | 40 | 117 | <0.001 | ||||

| CP1 | 123 (46) | 31 (29) | 18 (46) | 74 (63) | |||||

| AP or >CP1 | 67 (26) | 31 (29) | 11 (27) | 25 (21) | |||||

| BC | 75 (28) | 46 (42) | 11 (27) | 18 (16) | |||||

| Disease stage at allo-HCT | 361 | 139 | 62 | 160 | 0.07 | ||||

| CP1 | 139 (39) | 41 (30) | 25 (40) | 73 (46) | |||||

| AP or >CP1 | 163 (45) | 73 (52) | 26 (42) | 64 (40) | |||||

| BC | 59 (16) | 25 (18) | 11 (18) | 23 (14) | |||||

| Donor | 374 | 152 | 62 | 160 | 0.39 | ||||

| Identical sibling | 130 (35) | 59 (40) | 20 (32) | 51 (32) | |||||

| Other | 244 (65) | 93 (62) | 42 (68) | 109 (68) | |||||

| Recipient/donor sex match | 380 | 154 | 64 | 162 | 0.11 | ||||

| Male–female | 71 (19) | 31 (20) | 6 (9) | 34 (21) | |||||

| Other | 309 (81) | 123 (80) | 58 (91) | 128 (79) | |||||

| Recipient/donor CMV status | 374 | 149 | 63 | 162 | 0.88 | ||||

| neg/neg | 95 (25) | 37 (25) | 16 (25) | 42 (26) | |||||

| neg/pos | 38 (10) | 15 (10) | 5 (8) | 18 (11) | |||||

| pos/neg | 84 (23) | 29 (20) | 16 (25) | 39 (24) | |||||

| pos/pos | 157 (42) | 68 (45) | 26 (42) | 63 (39) | |||||

| Stem cell source | 382 | 155 | 63 | 164 | 0.89 | ||||

| BM | 73 (19) | 30 (19) | 13 (20) | 30 (18) | |||||

| PBSC | 295 (77) | 121 (78) | 47 (75) | 127 (78) | |||||

| CB | 14 (4) | 4 (3) | 3 (5) | 7 (4) | |||||

| T-cell depletion | 383 | 219 (57) | 155 | 85 (55) | 64 | 40 (62) | 164 | 94 (57) | 0.58 |

| TBI given | 383 | 113 (30) | 155 | 56 (36) | 64 | 12 (19) | 164 | 45 (27) | 0.28 |

| Conditioning regimen | 383 | 155 | 64 | 164 | 0.58 | ||||

| Myeloablative | 272 (71) | 114 (74) | 46 (72) | 112 (68) | |||||

| Non myeloablative | 111 (29) | 41 (26) | 18 (28) | 52 (32) | |||||

| EBMT score | 349 | 135 | 60 | 154 | 0.68 | ||||

| 1 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||||

| 2 | 24 (7) | 11 (8) | 4 (6.7) | 9 (6) | |||||

| 3 | 70 (20) | 28 (20.7) | 13 (21.7) | 29 (19) | |||||

| 4 | 146 (42) | 58 (43) | 23 (38.3) | 65 (42) | |||||

| 5 | 83 (24) | 27 (20) | 17 (28.3) | 39 (25) | |||||

| 6 | 22 (6) | 8 (6) | 2 (3.3) | 12 (8) | |||||

| 7 | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | |||||

EBMT score: disease stage at transplantation (0 for CP1, 1 for accelerated phase or for >CP1, and 2 for blastic crisis), age (0 for <20 years, 1 for 20–40 years, and 2 for >40 years), interval from diagnosis to transplant (0 for <1 year and 1 for ≥1 year), donor type (0 for an HLA-identical sibling and 1 for an unrelated donor), and donor–recipient sex match (1 for female donor for male recipient and 0 for all others).

CP chronic phase, AP accelerated phase, BC blastic crisis, PBSC peripheral blood stem cell, BM bone marrow, CB cordon blood.

Primary endpoints

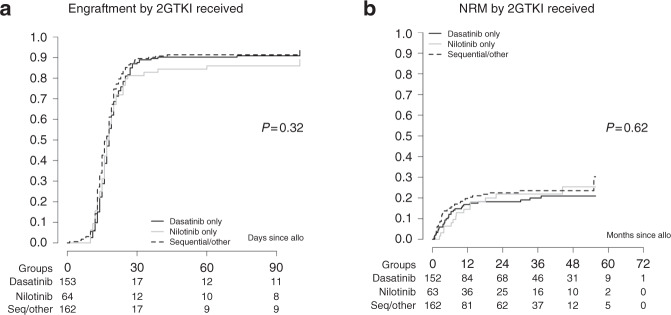

As 2GTKI therapy is associated with adverse hematologic effects, we specifically looked at the impact on engraftment. Engraftment occurrence was evaluated in 379/383 patients. Three hundred and fifty patients (92%) engrafted, while 10 patients (3%) experienced primary graft failure and 19 patients (5%) secondary graft failure. The median time to engraftment was 17 days (range 1–100) with no significant differences between the 2GTKI subgroups, P = 0.32 (Fig. 1a). From all the factors listed in the statistical paragraph, only stem cell source enter the Cox model of multivariable analysis with PBSC favoring engraftment (PBSC vs other source HR: 2.35, P < 0.001). This analysis revealed no significant differences between the 2GTKI subgroups regarding engraftment occurrence.

Fig. 1. Primary endpoints.

No significant differences were observed between the 2GTKI subgroups regarding engraftment (a) or non-relapse mortality (NRM) (b).

Regarding NRM, among 141 deaths at the time of the present analysis, 101 (71.6%) were without prior evidence of relapse. The main causes of NRM included GvHD in 50 patients and infection in 36 patients. The overall NRM was estimated at 18% (95% CI 14–22) at 12 months and 24% (95% CI 19–29) at 5 years. No significant differences between the 2GTKI subgroups were observed in univariate analysis, P = 0.62 (Fig. 1b). While several adjustment factors were associated in univariable analysis, only patient gender and performance status entered the Cox model of multivariable analysis. The absence of significant differences between the 2GTKI subgroups was confirmed, whereas only performance status (Karnofsky score <90 vs ≥90) had a statistically significant impact on NRM (HR: 1.67, 95% CI: 1.02–2.73). EBMT risk score (≥5 vs <5) had no significant impact on NRM.

Secondary endpoints

Transplant-related toxicity

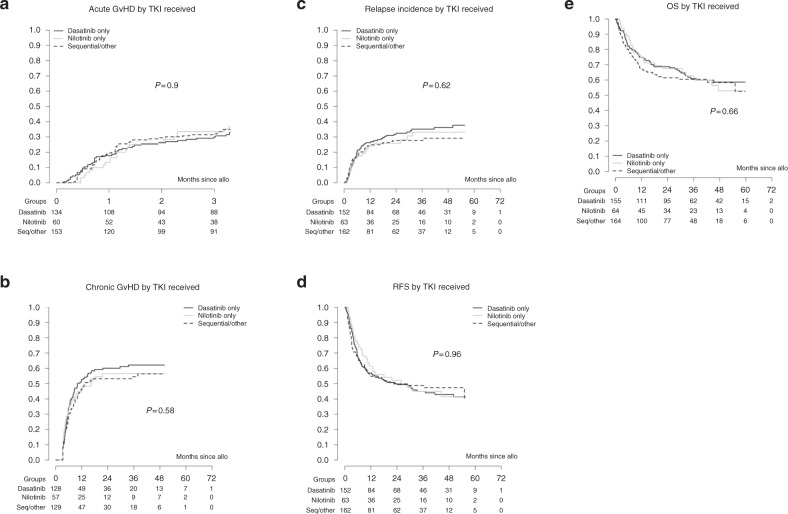

Acute GvHD (aGvHD) was evaluable in 347/383 patients (36 patients excluded due to missing data): the incidence of aGvHD grade II–IV was 34% (95% CI 29–39) with a median time to occurrence since transplant of 0.9 months (0.13–3.29 months). No significant difference was observed between the 2GTKI subgroups for aGvHD in univariable analysis (P = 0.9) (Fig. 2a). Several adjustment risk factors entered the multivariable model and all of them had a statistically significant impact on the occurrence of aGvHD: donor other than HLA-identical sibling (HR: 2.30, 95% CI: 1.48–3.57), TBI use (HR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.19–2.53), male patient/female donor vs other combinations (HR: 1.58 95% CI: 1.03–2.44), PBSC as stem cell source (HR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.09–3.00). However, there were no significant differences between the 2GTKI subgroups and this was confirmed when replacing risk factors by EBMT risk score that itself had a significant impact on aGvHD occurrence (HR: 1.76, 95% CI: 1.21–2.56). Chronic GvHD (cGvHD) was evaluable in 314/383 patients (18 patients excluded due to missing data, 51 because of death, lost to follow-up, or second transplantation before day 100). The 5-year incidence of cGvHD was 60% (95% CI 54–66). cGvHD occurred at a median of 5.7 months (3–61) post transplant. No significant difference between the different 2GTKI subgroups was observed (P = 0.58) (Fig. 2b). Hepatic SOS occurred in 6 cases (2%). Even if no comparison between 2GTKI subgroups is possible given the small number, it is noteworthy that 5/6 cases occurred in the dasatinib group, while the 6th case was in the combination group. Out of 299 evaluable patients, 195 (65%) developed a severe infection. There was no difference in infection occurrence between the three different 2GTKI subgroups (P = 0.8).

Fig. 2. Secondary endpoints.

No significant differences were observed between the 2GTKI subgroups regarding acute GvHD (a), chronic GvHD (b), relapse incidence (c), relapse-free survival (RFS) (d), and overall survival (OS) (e).

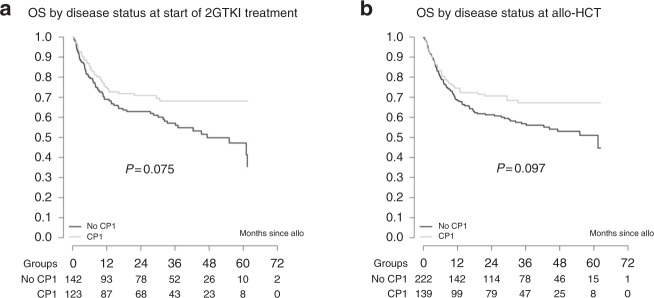

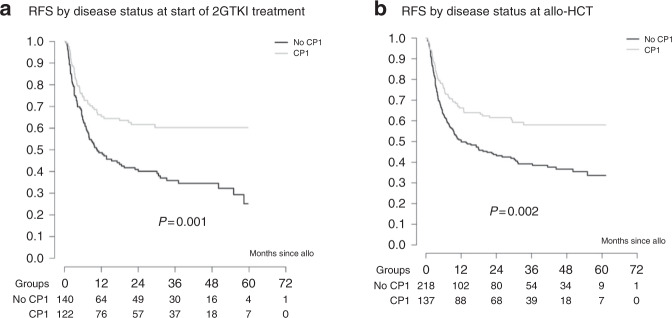

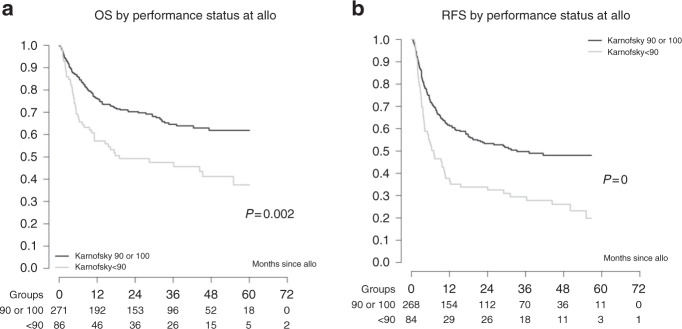

Relapse incidence at 2 and 5 years was estimated at 29% (95% CI 24–33) and 36% (95% CI 29–42), respectively, while RFS was 40% (95% CI 33–47) at 5 years. OS was 65.4% (95% CI 60–70) at 2 years and 56% (95% CI 50–62) at 5 years for all patients. No differences in post-transplant outcomes were found between the three different 2GTKI subgroups (Fig. 2c–e). On univariable analysis, advanced disease stage at start of 2GTKI treatment and at time of allo-HCT had a negative impact on overall (Fig. 3a, b) and RFS (Fig. 4a, b). So, 5-year OS was 67% for patients in CP1 at transplant, 57% for patients in AP or >CP1, and 37% for patients in BC. Poor performance status had also a negative impact on both OS (Fig. 5a) and RFS (Fig. 5b). Multivariable analysis for OS confirmed the absence of difference between 2GTKI groups (nilotinib only vs dasatinib only: HR = 1.16 95% CI: 0.70–1.91 and sequential/other vs dasatinib only: HR = 1.30, 95% CI: 0.88–1.90) in a model adjusted for performance status and disease status at transplant (Table 2, panel A). Similarly, multivariable analysis for RFS confirmed the absence of difference between 2GTKI groups (nilotinib only vs dasatinib only: HR = 0.99 95% CI: 0.58–1.70 and sequential/other vs dasatinib only: HR = 1.28, 95% CI: 0.85–1.92) in a model adjusted for performance status and disease status at transplant and at start of 2GTKI treatment (Table 2, panel B). On multivariable analysis poor performance status maintained its clear negative impact on both OS and PFS. We observed a trend for better OS in patients in CP1 at transplant and a trend for better PFS in patients in CP1 at transplant and those in CP1 at start of 2GTKI. Patients with EBMT risk score <5 showed a non-significant trend toward predicting better outcome (P = 0.0628).

Fig. 3. Impact of disease stage on overall survival (OS).

Advanced disease stage (defined as other than CP1) at start of 2GTKI treatment (a) and at time of allo-HCT (b) had a negative impact on OS.

Fig. 4. Impact of disease stage on relapse free-survival (RFS).

Advanced disease stage (defined as other than CP1) at start of 2GTKI treatment (a) and at time of allo-HCT (b) had a negative impact on RFS.

Fig. 5. Impact of perfomance status.

Poor performance status (defined as Karnofsky < 90) had a negative impact on overall survival (a) and relapse-free survival (b).

Table 2.

A Multivariate analysis of OS according to previous given 2GTKI and B multivariate analysis of RFS according to previous given 2GTKI.

| HR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||

| TKI: nilotinib vs dasatinib | 1.16 | 0.70, 1.91 | 0.567 |

| TKI: seq/other vs dasatinib | 1.30 | 0.88, 1.90 | 0.186 |

| Status at allo-HCT: CP1 vs no CP1 | 0.70 | 0.48, 1.03 | 0.068 |

| Karnofsky PS: <90 vs 90 or 100 | 1.90 | 1.32, 2.75 | 0.001 |

| B | |||

| TKI: nilotinib vs dasatinib | 0.99 | 0.58, 1.70 | 0.976 |

| TKI: seq/other vs dasatinib | 1.28 | 0.85, 1.92 | 0.244 |

| Status at allo-HCT: CP1 vs no CP1 | 0.64 | 0.41, 1.02 | 0.062 |

| Status at 2GTKI: CP1 vs no CP1 | 0.66 | 0.42, 1.05 | 0.078 |

| Karnofsky PS: <90 vs 90 or 100 | 2.23 | 1.51, 3.29 | <0.001 |

Discussion

Despite the excellent long-term survival for CML patients diagnosed in CP undergoing TKI treatment and a near normal life expectancy [30], allo-HCT continues to be an important treatment option for some patients [12]. However, the timing of the transplant has changed to third or fourth line after failure of or intolerance to at least one 2GTKI according to current recommendations [11]. Concerns regarding the feasibility and the safety of a subsequent allo-HCT are justified given some well-known side effects of 2GTKI. For instance, myelotoxicity could predispose to engraftment delay or liver toxicity to SOS. Careful evaluation of new therapeutic modalities regarding their potential impact on transplant-related mortality is therefore mandatory.

Our prospective study shows that pre-treatment with 2GTKI does not result in excessive transplant-related toxicity or mortality and does not have a detrimental effect on post-transplantation outcomes. The engraftment rate, the overall and RFS, the incidence of relapse, the NRM, and the rate of post-transplant complications are comparable to those of patients pre-treated with imatinib [13, 16] or TKI-naive [31, 32] patients demonstrating the feasibility of allo-HCT in patients previously treated with 2GTKI. Of note, the observed graft failure rate of 8% is higher than that reported in leukemia patients [33]. Although the primary graft failure rate (3%) was relatively low, it can be hypothesized that CML patients, independently of the type of TKI treatment, present a higher risk of graft failure because of the weak immunosuppressive effect of the disease and its treatment. The relative high rate of graft failure has been previously demonstrated [15, 16] with “only” 88–90% of imatinib-treated patients and 90% of TKI-naive patients achieving engraftment. It should be pointed out, though, that the comparison of outcomes with transplantation of the pre-TKI era is rather speculative because of the evolution of transplant modalities and the achievement of substantial reduction in transplant-related mortality in recent years.

Our results confirm prior observations: during the first 5 years of 2GTKI use, three retrospective studies [22–24] analyzing the outcome of a total of 43 patients who underwent allo-HCT following dasatinib or nilotinib treatment after imatinib failure provided no evidence for increased risk for graft failure or delayed engraftment, treatment-related organ toxicity or GVHD. Comparable results were demonstrated in a later observational prospective analysis of 28 CML patients [25]. Compared to previous studies, a prominent feature of the present analysis is the inclusion of a substantial number of patients treated with 2GTKI in a prospective manner. Moreover, the question about the individual influence of dasatinib and nilotinib has been addressed for the first time in this observational study with the comparison of the outcomes between the three 2GTKI subgroups. As might be expected, combination group patients presented a longer interval between diagnosis and transplantation, suggesting a longer TKI exposure duration. Of note, patients receiving dasatinib were more likely to proceed to allo-HCT in advanced phase than patients receiving nilotinib or both 2GTKI. This can be partially explained by the fact that dasatinib was given more often in earlier years, when ponatinib was not available yet and maintenance of CP before allo-HCT was less feasible [34]. Interestingly, we observed no differences in outcomes between the three 2GTKI subgroups. Our observation is in contrast to that of Kondo et al. [26] who analyzed the data of 237 patients for whom the number of pre-SCT TKI varied from one to three and identified the use of three TKIs before transplantation as a significant and independent adverse risk factor for prognosis because of a higher NRM rate. Although the number of TKIs was not specifically recorded in our study, we can safely assume that the majority of sequential treatment group patients were exposed to at least three TKIs but they did not experience a worse survival. This difference can be partially explained by the fact that in the Japanese study the proportion of patients with advanced disease at transplant was higher in patients with three TKIs than in patients with one TKI, whereas our three 2GTKI subgroups did not differ regarding to disease stage at transplant. It has been shown [16, 35–37] that pre-transplant TKI response impact on the post-transplantation outcome, while according to others [38], poor outcome after allo-HCT is associated with advanced disease at diagnosis but not disease status prior to transplantation. In our study, disease status at transplant was only of borderline significance for OS and RFS. Poor performance status at transplant had significantly negative impact on prognosis, although it is perhaps surprising and difficult to explain that EBMT risk group, based originally on CML data in the pre-TKI era [29], was not significantly predictive of outcome.

In our study, 101/383 patients (26.4%) died from causes other than disease relapse, figure not unexpected. GvHD was the leading cause of death with an incidence comparable to that observed in patients not treated with 2GTKIs [13, 31, 32] (50/383 patients,13%), followed by infections. Given the increasing experience on the efficacy of TKIs as GvHD treatment [39–41], the question of influence of the immunomodulatory potency of TKIs [42–48] on GvHD incidence and severity could be raised. Significantly lower incidence of cGvHD in patients pre-treated with imatinib compared with a historical group control has been reported [15], but it can be attributed to differences in GvHD prophylaxis and mainly a more frequent use of antithymocyte globulin in imatinib group. The lack of a lower GvHD incidence in our study was not surprising, given that the immunomodulatory effects of TKI prior to transplant are not expected to persist post transplantation and even less likely to affect the donor’s origin T-cell function.

Finally, only 2% of patients experienced SOS that is lower than the overall incidence of post-HCT SOS [49, 50] and importantly lower than the incidence of 25% reported previously [25] for pre-treated with 2GTKI patients who proceed to allo-HCT.

There are several caveats to these data, including missing detailed information on molecular or cytogenetic assessment of disease status, mutation status, and the indication for 2GTKI prior to allo-HCT. Information about therapy for relapse post allo-HCT was not analyzed. The absence of data regarding patients’ comorbidities, which could potentially explain the non-significant impact of EBMT score to outcome, is another limitation of our study. Nonetheless, these results highlight the safety and efficacy of allo-HCT after 2GTKIs, with comparable outcomes and no unexpected toxicity.

The time to proceed to allo-HCT remains highly controversial especially for patients still in chronic phase who fail second-line treatment. We consider that our study could be useful in defining risk-adapted strategies for patients with suboptimal response or failure to TKIs. It is obvious that an individualized risk-benefit assessment is needed in each patient, mainly regarding age, comorbidities, molecular aberrations, and donor availability. Despite considerable morbidity and mortality, allo-HCT offers a curative option with a very high survival rate for patients in CP. Given that pre-transplantation 2GTKI treatment does not adversely impact transplantation outcomes and that transplantation results seem better in case of CP1, the strategy to consider transplant before third-line treatment failure and loss of CP1 is a reasonable approach.

Supplementary information

Cross tables of disease stage at diagnosis vs disease stage at 2GTKI start vs disease stage at transplant

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Novartis (Novartis study code: CAMN107AGB02T). This study was partially presented as oral abstract at ASH congress in 2016 Blood 2016;128(22):628.

Author contributions

EO, YC and NK designed the study; MA, EM, RN, HS, PR, GH, PB, AG, AN, JAS, MR, JP, GVG, HLW, JH, H-JB, TDW, PH and IYA contributed data and reviewed the manuscript; SM-L, EO, MS, SI, YC and NK analyzed the data; SM-L and EO wrote the manuscript, and all the authors approved the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Université de Genève.

Competing interests

YC: Novartis, BMS, Pfizer, Incyte: advisory board; Novartis, BMS: travel grant. IYA: received honoraria from Novartis. JAS: none directly related to this project but otherwise received speaker fees; Jazz, Mallinckrodt, Janssen, Gilead; advisory board; Medac, and clinical trial IDMC membership; Kiadis. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Stavroula Masouridi-Levrat, Eduardo Olavarria.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41409-021-01472-x.

References

- 1.Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah NP, Guilhot F, Cortes JE, Schiffer CA, le Coutre P, Brümmendorf TH, et al. Long-term outcome with dasatinib after imatinib failure in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: follow-up of a phase 3 study. Blood. 2014;123:2317–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-532341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giles FJ, le Coutre PD, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Larson RA, Gattermann N, Ottmann OG, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant or imatinib-intolerant patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 48-month follow-up results of a phase II study. Leukemia. 2013;27:107–12. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hochhaus A, Saglio G, Hughes TP, Larson RA, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, et al. Long-term benefits and risks of frontline nilotinib vs imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 5-year update of the randomised results ENESTnd trial. Leukemia. 2016;30:1044–54. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, Bacarrani M, Mayer J, Boqué C, et al. Final 5-year study results of DASISION: the dasatinib versus imatinib study in treatment-naive chronic myeloid leukemia patients trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2333–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garg RJ, Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Quintás-Cardama A, Faderl S, Estrov Z, et al. The use of nilotinib or dasatinib after failure to 2 prior tyrosine kinase inhibitors: long-term follow-up. Blood. 2009;114:4361–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibrahim AR, Paliompeis C, Bua M, Milojkovic D, Szydlo R, Khorashad JS, et al. Efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as third-line therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase who have failed 2 prior lines of TKI therapy. Blood. 2010;116:5497–500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-291922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heiblig M, Rea D, Chrétien ML, Charbonnier A, Rousselot P, Coiteux V, et al. Ponatinib evaluation and safety in real-life CML patients failing more than two tyrosine kinase inhibitors: The PEARL observational study. Exp Hematol. 2018;67:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Innes A, Milojkovic D, Apperley JF. Allogeneic transplantation for CML in the TKI era: striking the right balance. Nat Rev. 2016;13:79–91. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, Hochhaus A, Soverini S, Apperley JF, et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood. 2013;122:872–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-501569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett J, Ito S. The role of stem cell transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia in the 21st century. Blood. 2015;125:3230–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-567784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lübking A, Dreimane A, Sandin F, Isaksson C, Märkevärn B, Brune M, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia in the TKI era: population-based data from the Swedish CML registry. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54:1764–74. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0513-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaucha JM, Prejzner W, Giebel S, Cooley TA, Szatkowski D, Kałwak K, et al. Imatinib therapy prior to myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:417–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deininger M, Schleuning M, Greinix H, Sayer HG, Fischer T, Martinez J, et al. The effect of prior exposure to imatinib on transplant-related mortality. Haematologica. 2006;91:452–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oehler VG, Gooley T, Snyder DS, Johnston L, Lin A, Cummings CC, et al. The effects of imatinib mesylate treatment before allogeneic transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:1782–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-031682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SJ, Kukreja M, Wang T, Giralt SA, Szer J, Arora M, et al. Impact of prior imatinib mesylate on the outcome of hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:3500–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-141689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saussele S, Lauseker M, Gratwohl A, Beelen DW, Bunjes D, Schwerdtfeger R, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo SCT) for chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era: evaluation of its impact within a subgroup of the randomized German CML Study IV. Blood. 2010;115:1880–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moslehi JJ, Deininger M. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor-associated cardiovascular toxicity in chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4210–418. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Lavallade H, Khoder A, Hart M, Sarvaria A, Sekine T, Alsuliman A, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors impair B-cell immune responses in CML through off-target inhibition of kinases important for cell signaling. Blood. 2013;122:227–38. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-465039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi Y, Nakamae H, Katayama T, Nakane T, Koh H, Nakamae M, et al. Different immunoprofiles in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with imatinib, nilotinib or dasatinib. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1084–9. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.647017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jabbour E, Cortes J, Kantarjian H, Giralt S, Andersson BS, Giles F, et al. Novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy before allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: no evidence for increased transplant-related toxicity. Cancer. 2007;110:340–4. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimoni A, Leiba M, Schleuning M, Martineau G, Renaud M, Koren-Michowitz M, et al. Prior treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitors dasatinib and nilotinib allows stem cell transplantation (SCT) in a less advanced disease phase and does not increase SCT Toxicity in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia and philadelphia positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:190–4. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breccia M, Palandri F, Iori AP, Colaci E, Latagliata R, Castagnetti F, et al. Second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors before allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia resistant to imatinib. Leuk Res. 2010;34:143–7. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piekarska A, Gil L, Prejzner W, Wiśniewski P, Leszczyńska A, Gniot M, et al. Pretransplantation use of the second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors has no negative impact on the HCT outcome. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:1891–7. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2457-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kondo T, Nagamura-Inoue T, Tojo A, Nagamura F, Uchida N, Nakamae H, et al. Clinical impact of pretransplant use of multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitors on the outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:902–8. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215–33. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gratwohl A, Hermans J, Goldman JM, Arcese W, Carreras E, Devergie A, et al. Risk assessment for patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia before allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation. Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lancet. 1998;352:1087–92. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann VS, Baccarani M, Hasford J, Castagnetti F, Di Raimondo F, Casado LF, et al. Treatment and outcome of 2904 CML patients from the EUTOS population-based registry. Leukemia. 2017;31:593–601. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gratwohl A, Brand R, Apperley J, Crawley C, Ruutu T, Corradini P, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia in Europe 2006: transplant activity, long-term data and current results. An analysis by the Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Haematologica. 2006;91:513–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crawley C, Szydlo R, Lalancette M, Bacigalupo A, Lange A, Brune M, et al. Outcomes of reduced-intensity transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia: an analysis of prognostic factors from the Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the EBMT. Blood. 2005;106:2969–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattsson J, Ringdén O, Storb R. Graft failure after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;14:1317–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molica M, Scalzulli E, Colafigli G, Foà R, Breccia M. Insights into the optimal use of ponatinib in patients with chronic phase chronic myeloid leukaemia. Ther Adv Hematol. 2019;10:1–14. doi: 10.1177/2040620719826444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jabbour E, Cortes J, Santos FPS, Jones D, O’Brien S, Rondon G, et al. Results of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia patients who failed tyrosine kinase inhibitors after developing BCR-ABL1 kinase domain mutations. Blood. 2011;117:3641–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair AP, Barnett MJ, Broady RC, Hogge DE, Song KW, Toze CL, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is an effective salvage therapy for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia presenting with advanced disease or failing treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1437–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khoury HJ, Kukreja M, Goldman JM, Wang T, Halter J, Arora M, et al. Prognostic factors for outcomes in allogeneic transplantation for CML in the imatinib era: a CIBMTR analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:810–6. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savoie ML, Bence-Bruckler I, Huebsch LB, Lalancette M, Hillis C, Walker I, et al. Canadian chronic myeloid leukemia outcomes post-transplant in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era. Leuk Res. 2018;73:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2018.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olivieri A, Locatelli F, Zecca M, Sanna A, Cimminiello M, Raimondi R, et al. Imatinib for refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease with fibrotic features. Blood. 2009;114:709–18. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osumi T, Miharu M, Tanaka R, Du W, Takahashi T, Shimada H. Imatinib is effective for prevention and improvement of fibrotic fasciitis as a manifestation of chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:139–40. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen GL, Carpenter PA, Broady R, Gregory TK, Johnston LJ, Storer BE, et al. Anti-platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha chain antibodies predict for response to nilotinib in steroid-refractory or -dependent chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:373–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seggewiss R, Loré K, Greiner E, Magnusson MK, Price DA, Douek DC, et al. Imatinib inhibits T-cell receptor mediated T-cell proliferation and activation in a dose-dependent manner. Blood. 2005;105:2473–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dietz AB, Souan L, Knutson GJ, Bulur PA, Litzow MR, Vuk-Pavlovic S. Imatinib mesylate inhibits T-cell proliferation in vitro and delayed-type hypersensitivity in vivo. Blood. 2004;104:1094–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Appel S, Balabanov S, Brümmendorf TH, Brossart P. Effects of imatinib on normal hematopoiesis and immune activation. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1082–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fei F, Yu Y, Schmitt A, Rojewski MT, Chen B, Greiner J, et al. Dasatinib exerts an immunosuppressive effect on CD8+ T cells specific for viral and leukaemia antigens. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:1297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schade AE, Schieven GL, Townsend R, Jankowska AM, Susulic V, Zhang R, et al. Dasatinib, a small-molecule protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, inhibits T-cell activation and proliferation. Blood. 2008;111:1366–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-084814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weichsel R, Dix C, Wooldridge L, Clement M, Fenton-May A, Sewell AK, et al. Profound inhibition of antigen-specific Tcell effector functions by dasatinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2484–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen J, Schmitt A, Chen B, Rojewski M, Rübeler V, Fei F, et al. Nilotinib hampers the proliferation and function of CD8+ T lymphocytes through inhibition of T cell receptor signalling. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:2107–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohty M, Malard F, Abecassis M, Aerts E, Alaskar AS, Aljurf M, et al. Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/venoocclusive disease: current situation and perspectives: a position statement from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:781–9. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coppell JA, Richardson PG, Soiffer R, Martin PL, Kernan NA, Chen A, et al. Hepatic veno-occlusive disease following stem cell transplantation: incidence, clinical course, and outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:157–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cross tables of disease stage at diagnosis vs disease stage at 2GTKI start vs disease stage at transplant