Abstract

Background

The evidence base behind new melanoma treatments is rapidly accumulating. This is not necessarily reflected in current guidance. A recent UK-based expert consensus statement, published in JPRAS, has called for updates to the widely accepted 2015 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline for melanoma (NG14). We aimed to compare the quality of NG14 to all other melanoma guidelines published since.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of PubMed, Medline, and online clinical practice guideline databases to identify melanoma guidelines published between 29th July 2015 and 23rd August 2021 providing recommendations for adjuvant treatment, radiotherapy, surgical management, or follow-up care. Three authors independently assessed the quality of identified guidelines using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument II (AGREE II) assessment tool, which measures six domains of guideline development. Inter-rater reliability was assessed by Kendall's coefficient of concordance (W).

Results

Twenty-nine guidelines were included and appraised with excellent concordance (Kendall's W for overall guideline score 0.88, p<0.001). Overall, melanoma guidelines scored highly in the domains of ‘Scope and purpose’ and ‘Clarity of presentation’, but poorly in the ‘Applicability’ domain. The NICE guideline on melanoma (NG14) achieved the best overall scores.

Conclusion

Melanoma treatment has advanced since NG14 was published, however, the NICE melanoma guideline is of higher quality than more recent alternatives. The planned update of NG14 in 2022 is in demand.

Keywords: Melanoma, Practice Guideline, Margins of Excision, Radiotherapy, Chemotherapy

Introduction

Melanoma treatment options are rapidly evolving1. Checkpoint and v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF) inhibitors have significantly improved survival rates in advanced disease2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and recent high profile trials have challenged previous approaches to lymph node and skin surgery8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13. In a rapidly advancing field, guidelines quickly become outdated. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is internationally renowned for its rigorous, multi-stakeholder approach to guideline development. However, a recent consensus statement of UK melanoma experts has challenged the widely adopted 2015 NICE guidance for melanoma (NG14)14 in light of landmark trials published over the last five years, including Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II (MSLT-II) and the Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group-Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (DeCOG-SLT)8,9,15.

The quality of guidelines can be assessed according to the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) assessment tool, a widely accepted instrument for guideline quality appraisal, with established construct validity16, 17, 18. The AGREE II assessment tool evaluates the quality and reporting of practice guidelines using 23 items across six domains, namly ‘Scope and purpose’, ‘Stakeholder involvement’, ‘Rigour of development’, ‘Clarity of presentation’, ‘Applicability’, and ‘Editorial independence’. Each item is scored on an ordinal scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) according to AGREE II manual16 and an additional overall score is assigned to each guideline.

The objective of this study was to systematically appraise the quality of melanoma guidelines developed since the NG14 was published, and compare these more recent alternatives to NG14, using the AGREE II criteria.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The study protocol was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework19 and conducted in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement20.

Search strategy

The search strategy was designed with the assistance of a search strategist (Suppl. 1). PubMed and Medline databases were searched from 29th July 2015 until 23rd August 2021.

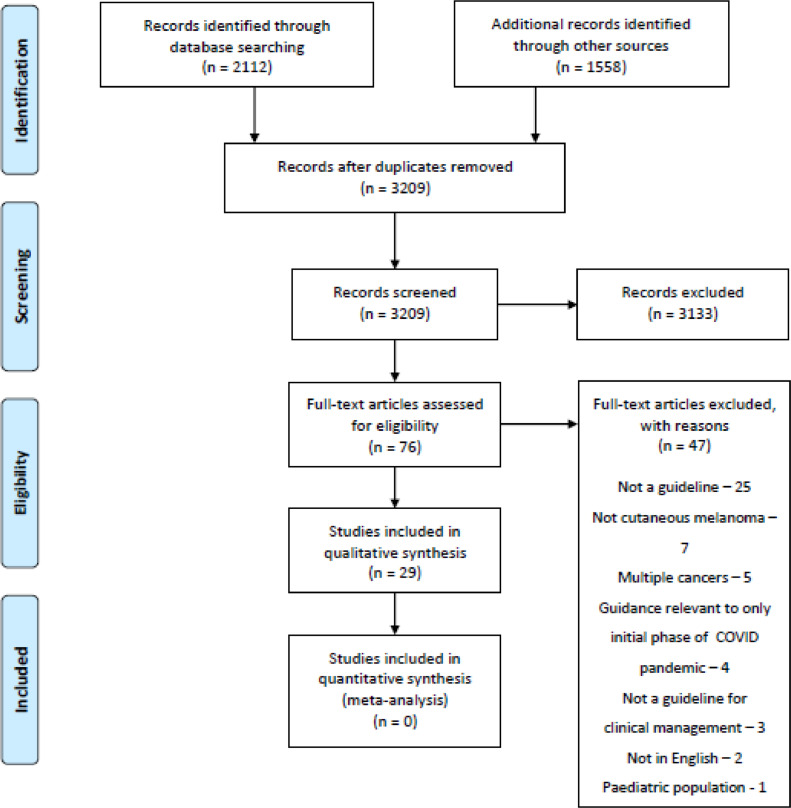

Additionally, the following clinical practice guidelines databases were searched with the search keywords: “melanoma”: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; Canadian clinical practice guidelines InfoBase: Clinical Practice Guidelines Database; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines; and Guidelines International Network. A further search was carried out in the Turning Research into Practice (TRIP) database with the search term “melanoma” followed by using the filter tools: “guidelines” and “since 2015”. Search results were screened by an author CJ (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Eligibility criteria

Results from the search were included if they provided recommendations on at least one of the following: adjuvant treatment, radiotherapy, surgical management, or follow-up care for cutaneous melanoma, and were developed after the publication of the NG14 (29th July 2015).

Publications were excluded if they were not in the English language, were for the pediatric population only, were aimed at nurses only, provided guidelines for multiple cancers, and recommendations were relevant only to care during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

AGREE II assessment

Three assessors independently appraised the candidate guidelines for malignant melanoma management using the “My AGREE PLUS” platform21. Guidelines were assigned ratings on an ordinal 1-7 scale for 23 items across six domains. Assessors also assigned a global rating out of seven scales and provided an overall judgment on the appropriateness of the guidelines for use with or without modifications.

To aid better interpretation, overall scaled percentage scores were calculated for each item, domain, and guideline, by summing the scores of individual assessors and presenting them as a percentage of the maximum attainable score. To do this, we used the calculation specified in the AGREE II user manual16. We calculated inter-observer reliability using both Fleiss kappa and Kendall's coefficient of concordance (W).

Results

Guideline Search

A total of 3670 articles were identified by the search strategy, of which 461 duplicates were removed. The remaining 3209 articles were screened by their title and abstract; during screening 3133 articles were excluded. Next, 76 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of them again were excluded (justifications are provided in Fig. 1), leaving 29 articles14,15,22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 for appraisal with the AGREE II tool. A summary of the characteristics of the articles appraised in this review is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scaled guideline percentage scores and overall ratings.

| Title | Year Published | Author | Scaled guideline percentage score (%) | Overall judgment - fit for purpose? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma Assessment and Management14 | 2015 | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, UK | 94.2 | Yes |

| SIGN 146 - Cutaneous Melanoma50 | 2017 | Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Scotland | 89.4 | Yes |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Melanoma48 | 2020 | Cancer Council, Australia | 80.4 | Yes |

| Systemic Therapy for Melanoma: ASCO Guideline24 | 2020 | American Society of Clinical Oncology, US | 80.4 | Yes |

| Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Management of Regional Lymph Nodes in Melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update44 | 2017 | American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology, US | 79.7 | Yes |

| Primary Excision Margins and Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Cutaneous Melanoma38 | 2017 | Cancer Care Ontario, Canada | 78.5 | Yes |

| Follow-up of Patients with Cutaneous Melanoma who were treated with Curative Intent38 | 2015 | Cancer Care Ontario, Canada | 75.8 | Yes |

| Locoregional management of in-transit metastasis in melanoma25 | 2020 | Cancer Care Ontario, Canada | 75.8 | Yes |

| Systemic Adjuvant Therapy for Adult Patients at High Risk for Recurrent Cutaneous or Mucosal Melanoma: An Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) Clinical Practice Guideline49 | 2020 | Cancer Care Ontario, Canada | 75.1 | Yes |

| The Use of Adjuvant Radiation Therapy for Curatively Resected Cutaneous Melanoma31 | 2016 | Cancer Care Ontario, Canada | 72 | Yes |

| Guidelines of Care for the Management of Primary Cutaneous Melanoma45 | 2018 | American Academy of Dermatology, US | 66.4 | Yes with modifications |

| An Update on the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer Consensus Statement on Tumor Immunotherapy for the Treatment of Cutaneous Melanoma: Version 2.043 | 2018 | Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer | 65.9 | Yes with modifications |

| Japanese Dermatological Association Guidelines: Outlines of Guidelines for Cutaneous Melanoma 201941 | 2019 | Japanese Dermatological Association, Japan | 64.7 | Yes |

| European Consensus-Based Interdisciplinary Guideline for Melanoma. Part 2: Treatment e Update 201942 | 2019 | European Dermatology Forum, European Association of Dermato-Oncology, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer | 60.4 | Yes |

| Sentinel Node Biopsy in Primary Cutaneous Melanoma29 | 2016 | Alberta Health Services, Canada | 56.3 | Yes |

| Guidelines of the Brazilian Dermatology Society for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow Up of Primary Cutaneous Melanoma – Part I and Part II36,37 | 2015 | Brazilian Dermatological Society, Brazil | 55.1 | Yes with modifications |

| French Updated Recommendations in Stage I To III Melanoma Treatment and Management35 | 2017 | Guillot et al. | 53.4 | Yes with modifications |

| Systemic Anti-Cancer Therapy of Patients with Metastatic Melanoma28 | 2017 | National Cancer Control Programme, Ireland | 52.9 | Yes with modifications |

| Cutaneous Melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow Up40 | 2019 | European Society for Medical Oncology | 50.7 | No |

| Current Role of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in the Management of Cutaneous Melanoma: A UK Consensus Statement15 | 2020 | Peach et al. | 50 | Yes with modifications |

| Spanish Multidisciplinary Melanoma Group (GEM) Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Advanced Melanoma33 | 2015 | Spanish Multidisciplinary Melanoma Group, Spain | 42.8 | No |

| Cutaneous Melanoma, Version 2.201939 | 2019 | National Comprehensive Cancer Network, US | 42.3 | Yes with modifications |

| ESMO consensus conference recommendations on the management of locoregional [and metastatic] melanoma: under the auspices of the ESMO Guidelines Committee26,27 | 2020 | European Society for Medical Oncology | 40.3 | Yes with modifications |

| EANM Practice Guidelines for Lymphoscintigraphy and Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Melanoma34 | 2015 | European Association of Nuclear Medicine | 37 | No |

| Radiological imaging of melanoma: a review to guide clinical practice in New Zealand22 | 2021 | Francis et al. | 35.7 | No |

| SEOM clinical guideline for the management of cutaneous melanoma23 | 2021 | Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica, Spain | 32.9 | No |

| The Updated Swiss Guidelines 2016 for the Treatment and Follow-Up of Cutaneous Melanoma32 | 2016 | Dummer et al | 32.4 | No |

| SEOM Clinical Guideline for the Management of Malignant Melanoma30 | 2017 | Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica, Spain | 28.7 | No |

| Chinese Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Melanoma 201846 | 2018 | National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, China | 18.6 | No |

Four guidelines51, 52, 53, 54 were excluded because they provided recommendations relevant to only the temporary disruption to care caused by the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Examples of their recommendations include emphasizing the importance of in-person examination52,53, review of requirement and/or timing of routine clinics51,53,54, opting for the longest approved interval between immunotherapy treatments53, and deferring SLB52,54.

Guideline appraisal

Two guidelines were given a global rating of 7/7 by all assessors: NG14 (the 2015 NICE guideline)14, and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) “SIGN 146: cutaneous melanoma” guideline50. The median scaled guideline percentage score (representing all raters’ assessments of a guideline, across all items) was 58.2%. No guideline received the maximum scaled guideline percentage score. The highest guideline percentage score (94%) was awarded to NG14.

Inter-rater reliability

Fleiss kappa value, assessing agreement of specific numeric ratings, ranged from -0.11 to 0.23 for item scores. Kendell's coefficient of concordance (W), assessing agreement of rankings, ranged from 0.52−0.88 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Inter-rater reliability statistics for each item (1-23) in AGREE II, judgment (if fit for purpose), and rating of the overall score.

| Item | Fleiss Kappa (p value) | Kendall's W (p value) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.12 (.030) | 0.68 (<.001) |

| 2 | 0.05 (.374) | 0.80 (<.001) |

| 3 | 0.11 (.057) | 0.80 (<.001) |

| 4 | 0.02 (.678) | 0.74 (<.001) |

| 5 | 0.13 (.022) | 0.60 (.006) |

| 6 | 0.18 (<.001) | 0.71 (<.001) |

| 7 | 0.27 (<.001) | 0.86 (<.001) |

| 8 | 0.13 (.004) | 0.78 (<.001) |

| 9 | -0.06 (.232) | 0.63 (.003) |

| 10 | 0.12 (.001) | 0.81 (<.001) |

| 11 | <0.01 (.985) | 0.52 (.031) |

| 12 | 0.07 (.156) | 0.75 (<.001) |

| 13 | 0.23 (.010) | 0.82 (<.001) |

| 14 | 0.15 (.004) | 0.70 (<.001) |

| 15 | <0.01 (.955) | 0.65 (.002) |

| 16 | 0.02 (.795) | 0.59 (.007) |

| 17 | 0.11 (.047) | 0.76 (<.001) |

| 18 | -0.03 (.586) | 0.71 (<.001) |

| 19 | 0.03 (.580) | 0.70 (<.001) |

| 20 | 0.05 (.356) | 0.65 (.002) |

| 21 | -0.11 (.033) | 0.52 (.030) |

| 22 | 0.12 (.022) | 0.67 (.001) |

| 23 | 0.07 (.201) | 0.68 (<.001) |

| Judgment | 0.41 (<.001) | 0.48 (.065) |

| Overall score | 0.19 (<.001) | 0.88 (<.001) |

Discussion

The widely adopted NG14 guidance14 on the management of melanoma is now considered partly outdated by expert consensus15. In light of advances in adjuvant treatment for stage III disease, experts have called for broader indications for sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), and the findings of MSLT-29 and DeCOG-SLT8 suggest that completion lymphadenectomy is not necessarily indicated in all patients with a positive SLNB. This guidance has been reflected in 14 out of 2915,28, 29, 30, 31, 32,38,47,49,55 guidelines published since NG14, although none of the guidelines reviewed in this study equaled NG14’s development methodology, as determined by the AGREE II instrument.

NG1414 outscored other guidelines because it included additional elements such as patient and public involvement in guideline creation, external review of recommendations, auditing criteria, and support for guideline implementation.

The AGREE II tool enables users to rank guidelines by methodological quality, but there are no empirical data to suggest guidelines with higher AGREE II scores achieve better clinical outcomes, and there is no guidance on what scores guidelines should achieve before their uptake in routine clinical practice. In the current study, authors had good concordance on determining which guidelines were of comparatively superior quality (Kendall's W statistic), but there was poor agreement on specific scores (Fleiss kappa statistic). This suggests that the AGREE II tool is reliable and appropriate for ranking guidelines against each other, though the precise scores vary considerably depending on the assessor and cannot be used to quantify differences in quality between guidelines.

Another limitation of the AGREE II tool is that it is largely limited to only assessing the methodological quality of guideline development and how well guidelines reflect current evidence is assessed only in one item. Guidelines can score highly even if they are outdated, as was the case with NG1414 and SIGN 14650 in this study. In addition, guidelines based on expert consensus can score poorly because they lack a systematic review of the evidence. This could lead to unfair exclusion of otherwise methodological rigorous consensus statements that have a valuable role to play in areas where evidence is scarce26,27,43.

Conclusion

This paper suggests that guidelines published since NG1414 have not met the same methodological development standards. More updates to NG1414 are needed and these are planned for 202255. A pragmatic approach should be taken to melanoma management, with careful consideration given to the results of landmark trials published since the development of NG1414.

Declaration of Competing Interest

At the time of writing, Conrad J. Harrison was enrolled on the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) scholarship program, and as such could receive expenses from NICE for attendance at NICE events. No specific funding was received for this work.

Chloe Jacklin, Matthew Tan and Sanskrithi Sravanam have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Tatjana Petrinic (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford) for designing the search strategy.

Funding Support

Conrad J. Harrison is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Research Fellowship (NIHR300684). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical Approval

Since no animal or human studies are involved and this is a review paper, no ethics approval is required.

Footnotes

This work has been presented at the Association of Surgeons in Training (ASiT) MedAll Virtual Surgical Summit 2020; 17 th October 2020. Presented by Chloe Jacklin as a poster entitled: Appraisal of International Guidelines for Malignant Melanoma management using the AGREE II assessment tool.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2021.11.002.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, et al. Melanoma. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):971–984. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darvin P, Toor SM, Nair VS, Elkord E. Immune checkpoint inhibitors : recent progress and potential biomarkers. Exp Mol Med. 2018:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eggermont AMM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): A randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(5):522–530. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eggermont AMM, Chiarion-sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1845–1855. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1789–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1824–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long G.V., Hauschild A, Santinami M, et al. Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1813–1823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leiter U, Stadler R, Mauch C, et al. Complete lymph node dissection versus no dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy positive melanoma (DeCOG-SLT): a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):757–767. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faries B, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Completion dissection or observation for sentinel-node metastasis in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2211–2222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinn MJ, Robyn P, Saw M, Kerwin F, Spillane AJ. The Optimum Excision Margin and Regional Node Management A Retrospective Study of 1587 Patients Treated at a Single Center. 2014;260(6) doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes AJ, Maynard L, Coombes G, et al. Articles Wide versus narrow excision margins for high-risk, primary cutaneous melanomas: long-term follow-up of survival in a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:184–192. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00482-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawlani R, Rawlani V, Qureshi HA, Kim JYS, Wayne JD. Reducing Margins of Wide Local Excision in Head and Neck Melanoma for Function and Cosmesis : 5-Year Local Recurrence-Free Survival. 2015;(December 2014):795–799. doi: 10.1002/jso.23886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haydu LE, Stollman JT, Scolyer RA, et al. Minimum Safe Pathologic Excision Margins for Primary Cutaneous Melanomas (1 –2 mm in Thickness): Analysis of 2131 Patients Treated at a Single Center. 2016:1071–1081. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4575-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NICE. Melanoma: Assessment and Management NICE Guideline NG14 - Full Guideline.; 2015. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng14. Accessed January 3, 2021.

- 15.Peach H, Board R, Cook M, et al. Current role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in the management of cutaneous melanoma: A UK consensus statement. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Cmaj. 2010;182(18):839–842. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 1: Performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. Cmaj. 2010;182(10):1045–1052. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. Cmaj. 2010;182(10) doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.OSF | Appraisal of International Guidelines for Malignant Melanoma Management using the AGREE II assessment tool. https://osf.io/je3xz/. Accessed January 4, 2021.

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AGREE II. AGREE II My PLUS Platform. https://www.agreetrust.org/my-agree/. Accessed June 21, 2020.

- 22.Francis V, Sehji T, Barnett M, Martin RCW. Radiological imaging of melanoma: a review to guide clinical practice in New Zealand. N Z Med J. [PubMed]

- 23.Majem M, Manzano J L, Marquez-Rodas I, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for the management of cutaneous melanoma. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;2094:23. doi: 10.1007/s12094-020-02539-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seth R, Messersmith H, Kaur V, et al. Systemic Therapy for Melanoma: ASCO Guideline. https://doi.org/101200/JCO2000198. 2020;38(33):3947-3970. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Wright Md Med FC, Kellett S, Look NJ, et al. Locoregional management of in-transit metastasis in melanoma: an Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) clinical practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2020;27(3) doi: 10.3747/co.27.6523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michielin O, Van Akkooi A, Lorigan P, et al. ESMO consensus conference recommendations on the management of locoregional melanoma: under the auspices of the ESMO Guidelines Committee. J J Grob. 2020;14:31. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keilholz U, Ascierto PA, Dummer R, et al. ESMO consensus conference recommendations on the management of metastatic melanoma: under the auspices of the ESMO Guidelines Committee. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1435–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Cancer Control Programme I. Systemic anti-cancer therapy of patients with metastatic melanoma. https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/5/cancer/about/systemic-anti-cancer-therapy-of-patients-with-metastatic-melanoma.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed January 13, 2021.

- 29.Alberta Health Services Guideline Resource Unit. Sentinel Node Biopsy in Primary Cutaneous Melanoma; https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/cancer/if-hp-cancer-guide-cu011-regional-node-dissection.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed January 13, 2021.

- 30.Berrocal A, Arance A, Castellon VE, et al. SEOM clinical guideline for the management of malignant melanoma (2017) Clin Transl Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1768-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun A, Souter LH, Hanna TP, et al. A Quality Initiative of the The Use of Adjuvant Radiation Therapy for Curatively Resected Cutaneous Melanoma. 2016;8(9) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dummer R, Siano M, Hunger RE, et al. The updated Swiss guidelines 2016 for the treatment and follow-up of cutaneous melanoma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016 doi: 10.4414/smw.2016.14279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berrocal A, Espinosa E, Marín S, et al. Spanish Multidisciplinary Melanoma Group (GEM) guidelines for the management of patients with advanced melanoma. Eur J Dermatology. 2015 doi: 10.1684/ejd.2015.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bluemel C, Herrmann K, Giammarile F, et al. EANM practice guidelines for lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guillot B, Dalac S, Denis MG, et al. French updated recommendations in Stage I to III melanoma treatment and management. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jdv.14064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castro LGM, Duprat Neto JP, Di Giacomo THB, et al. Brazilian guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of primary cutaneous melanoma - Part II. An Bras Dermatol. 2016 doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castro LGM, Messina MC, Loureiro W, et al. Guidelines of the Brazilian Dermatology Society for diagnosis, treatment and follow up of primary cutaneous melanoma - Part I. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(6):851–861. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20154707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright FC, Souter LH, Kellett S, et al. Primary Excision Margins, Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy, and Completion Lymph Node Dissection in Cutaneous MelanomA: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(4):541–550. doi: 10.3747/co.26.4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coit DG, Thompson JA, Albertini MR, et al. Cutaneous melanoma, version 2.2019. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2019;17(4):367–402. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michielin O, Van Akkooi ACJ, Ascierto PA, Dummer R, Keilholz U. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(12):1884–1901. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura Y, Asai J, Igaki H, et al. Japanese Dermatological Association Guidelines: Outlines of guidelines for cutaneous melanoma 2019. J Dermatol. 2020;47(2):89–103. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garbe C, Amaral T, Peris K, et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 2: Treatment – Update 2019. Eur J Cancer. 2020;126:159–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan RJ, Atkins MB, Kirkwood JM, et al. An update on the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer consensus statement on tumor immunotherapy for the treatment of cutaneous melanoma: Version 2.0. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):1–23. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0362-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong SL, Faries MB, Kennedy EB, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and management of regional lymph nodes in Melanoma: American society of clinical oncology and society of surgical oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):399–413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.7724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swetter SM, Tsao H, Bichakjian CK, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):208–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Health Commission of PRC N. Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of melanoma 2018 (English version) Chinese J Cancer Res. 2019;31(4):578–585. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2019.04.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baetz TD, Fletcher GG, Knight G, et al. Systemic adjuvant therapy for adult patients at high risk for recurrent melanoma: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;87(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Australia CC. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of melanoma - Clinical Guidelines Wiki. https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:Melanoma#. Published 2020. Accessed January 3, 2021.

- 49.Petrella TM, Fletcher GG, Knight Md G, et al. Systemic adjuvant therapy for adult patients at high risk for recurrent cutaneous or mucosal melanoma: an Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) clinical practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2020;27(1) doi: 10.3747/co.27.5933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.SIGN. SIGN 146 • Cutaneous Melanoma.; 2017. https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1082/sign146.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2021.

- 51.Nahm SH, Rembielak A, Peach H, Lorigan PC. Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Melanoma during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Surgery, Systemic Anti-cancer Therapy, Radiotherapy and Follow-up. Clin Oncol. 2021;33(1):e54–e57. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Cancer Control Programme NCCP advice for Medical Professionals on the Management of patients with Suspected or Diagnosed Malignant Melanoma or Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer in response to the current novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Covid-19 HSE Clin Guid Evid. 2020:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arenbergerova M, Lallas A, Nagore E, et al. Position statement of the EADV Melanoma Task Force on recommendations for the management of cutaneous melanoma patients during COVID-19. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2021;35(7):e427–e428. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.British Association of Dermatologists. COVID-19: Clinical Guidance for the Management of Skin Cancer Patients during the Coronavirus Pandemic. https://www.bad.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/covid-19. Published 2020. Accessed September 29, 2021.

- 55.NICE. Melanoma: assessment and management - In development [GID-NG10155]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ng10155. Accessed July 8, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.