Abstract

Introduction

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is an acute life-threatening complication in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Causes, underlying pathophysiology, and mortality differ significantly by diabetes type, which initial treatment is dependent on, but few reports on these differences are available. This study aimed to clarify differences in clinical characteristics between the diabetes types to extract important clinical clues for preventing DKA and ensuring appropriate initial treatment in the emergency room.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical presentation of 24 T1DM patients and 13 T2DM patients admitted with DKA to Kobe City Medical Center West Hospital between April 2006 and December 2018.

Results

In T1DM, the main causes were insulin omission and new onset, and important factors were also misdiagnosis with consequent inappropriate insulin prescription and older age with dementia. In T2DM, the main causes were infection and excessive soft drink consumption. For all soft drink ketosis patients, this was the first presentation of diabetes. The main complaint differed between diabetes types. Vomiting was a characteristic symptom in T1DM DKA; most T2DM DKA patients presented with generalized malaise or decreased level of consciousness. On blood examination, serum potassium level was higher and HbA1c was lower in T1DM DKA.

Conclusions

To prevent DKA, it is important to provide social support for elderly patients with T1DM DKA and lifestyle intervention for younger T2DM or obese patients. Vomiting and serum potassium levels contribute to the classification of diabetes type and subsequent initial treatment in the emergency room.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13340-021-00539-w.

Keywords: Ketoacidosis, Vomiting, Hyperkalemia

Introduction

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a life-threatening acute complication of type 1 (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which is typically marked by acidosis, ketosis, and hyperglycemia, all requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Generally, DKA is associated with fatal complications. The condition itself is a hypercoagulable state that can potentially result in strokes, myocardial infarctions, and intestinal ischemia. Moreover, certain complications associated with DKA treatment may occur as well. Excessive insulin administration, for one, causes hypokalemia and hypoglycemia, which sometimes result in arrhythmias and cardiac arrest. Cerebral edema is another complication typically observed in children [1], although its mortality rate is higher in adults [2]. Therefore, DKA is a serious diabetic emergency, and its acute management is important in preventing treatment-associated complications.

DKA occurrence in the United States has been found to increase over the past decade [3]. Similarly, admissions for DKA in England was found to have increased between 1998 and 2007, occurring alongside an annual increase in T2DM DKA but without significant changes in T1DM DKA incidence. There was also no change in all-cause mortality, which was found to be not affected by diabetes type [4]. Previous studies have reported that mortality rates in DKA were generally around 1%–5% [5, 6], but some studies have shown that older patients had higher mortality [2, 4, 7], suggesting that DKA prevention and treatment should be discussed based on the patients’ background characteristics, including diabetes type, age, and complications.

Many studies have also shown differences in the causes of DKA based on diabetes type. Particularly, the most common precipitating factor for T1DM DKA was absolute insulin deficiency due to insulin injection cessation during acute illness, periods of psychological distress, or poor adherence. New-onset T1DM was also found to be a common cause of DKA. On the other hand, frequently reported causes of T2DM DKA were severe insulin resistance caused by infection [1] and excessive consumption of sugar-containing soft drinks. Despite the critically different causes and underlying pathophysiology between diabetes types 1 and 2, little has been reported on their differences in clinical characteristics and laboratory results.

Given this background, this study analyzed the differences in clinical and biochemical characteristics between T1DM DKA and T2DM DKA patients. To date and to the best of our knowledge, there have yet to be large-scale studies on DKA admissions in Japan. Furthermore, the number of T2DM patients and older diabetic patients secondary to aging have been increasing in the Japanese population. This situation in addition to the background of the study prompted us to conduct a detailed analysis of DKA based on diabetes type in Japan, the results of which should prove helpful in preventing DKA and ensuring appropriate initial treatment.

Materials and methods

Patients

We analyzed the medical records of 58 patients who were admitted with a diagnosis of DKA between April 2006 and December 2018 at the Kobe City Medical Center West Hospital. We then divided the patients into two groups, T1DM and T2DM, based on their diagnosis at the time of discharge, excluding those with other types of diabetes (e.g., gestational diabetes) and who drank excessive amounts of alcohol. We also excluded data from the second visit for recurrent DKA patients and data from euglycemic DKA patients. Following inclusion of participants, we retrospectively analyzed patient complaints, clinical history, and blood test results from their medical records in the emergency room.

HbA1c values (%) measured in March 2011 or earlier were estimated as the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program equivalent value (%), calculated using the formula HbA1c (%) = 1.02 × HbA1c (JDS) + 0.25%, considering the relational expression of HbA1c (%), which was measured using high performance liquid chromatography as defined by the Japan Diabetes Society.

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Committee on Human Experimentation (Kobe City Medical Center West Hospital, Approval No. 17–021, date of approval: February 28, 2018) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its subsequent revision. Using only the existing materials declared in this manuscript, the study was considered exempt from the need for an informed consent.

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnostic criteria for DKA included metabolic acidosis (pH < 7.3), ketonemia, and a blood glucose level > 250 mg/dL, as defined by the American Diabetes Association [1]. Moreover, diagnostic criteria for type 1 diabetes required continuous insulin therapy after diabetes diagnosis and positive test results for anti-islet autoantibodies. Meanwhile, patients who were negative for these autoantibodies but were found to be exhausting their endogenous insulin secretion were also diagnosed with type 1 diabetes [8].

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the Statcel 3 (OMS Inc., Tokorozawa, Japan) and GraphPad PRISM software (version 5.0; MDF Co., Tokyo, Japan). Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and statistical significance was assessed using either the Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Statistical significance for all analyses was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Background characteristics

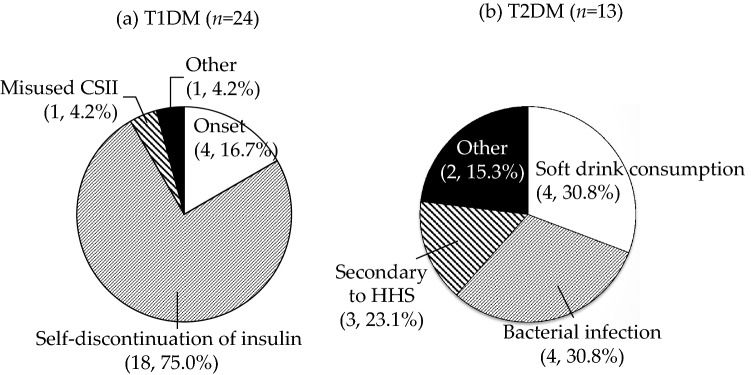

We reviewed a total of 44 T1DM DKA cases (24 patients) and 14 T2DM DKA cases (14 patients), as shown in the study flowchart (Fig. 1). Among the 44 T1DM DKA patients, 20 of them had recurrent DKA, all involving insulin omission due to poor adherence (7 patients, 3 of whom were elderly T1DM patients with dementia), and we therefore excluded their clinical information for the second and subsequent admissions for these 7 patients, leaving exactly 24 cases of DKA admissions in 24 T1DM patients for analysis. On the other hand, none of the 14 T2DM patients had recurrent episodes of DKA, but one patient had euglycemic DKA due to SGLT2 inhibitor therapy, prompting his exclusion from the analysis. Therefore, only 13 cases of DKA admissions in T2DM patients were analyzed.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing case selection

Various causes and clinical characteristics noted in the emergency room were analyzed for all 37 patients, showing no significant differences in age, sex ratio, or BMI between the two groups. Baseline characteristics of the included patients are further shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical characteristics between diabetes types

| T1DM (n = 24) | T2DM (n = 13) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 50.5 (15–82) | 56.0 (28–80) | 0.504 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 14 (60.9) | 7 (53.8) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.2 (17.1–29.4) | 21.2 (16.1–33.8) | 0.16 |

| History of diabetes | |||

| First presentation of diabetes, n (%) | 4 (16.7) | 6 (46.1) | |

| Under treatment, n (%) | 20 (79.1) | 3 (23.0) | |

| MDI 12(50.0) | OHA 2 (15.4) | ||

| CSII 2(8.4) | Biphasic insulin 1(7.7) | ||

| Biphasic insulin 4(16.7) | |||

| BOT 1(4.2) | |||

| OHA 1(4.2) | |||

| Interruption, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.3) | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | |

Data: age and BMI are expressed as median (whole range). Analysis: out using Mann–Whitney U test. Diabetes history and treatment are expressed number of patients (%)

BMI body mass index, BOT basal supported oral therapy, CSII continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, MDI multiple daily injections, OHA oral hypoglycemic agent, T1DM type 1 diabetes, T2DM type 2 diabetes

A retrospective analysis of clinical history and medical interviews revealed the following information. In the 24 T1DM DKA patients, the mean age was noted to be 50.7 ± 17.4 years, finding that T1DM DKA could have possibly developed at all ages. Of these 24 T1DM DKA patients, 4 (16.7%) were newly diagnosed with diabetes during their hospital stay. Of the remaining 20 T1DM DKA patients who had been previously diagnosed with diabetes, 12 had been treated with multiple daily injections (MDI), 2 had received continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), 5 had received biphasic insulin or basal supported oral therapy (BOT), and 1 had received oral hypoglycemic agent (OHA). Aside from the five patients who were prescribed biphasic insulin or OHA due to misdiagnosis and had been treated as having T2DM, all were diagnosed with T1DM during their hospital stay. The other patients who had been treated with MDI, CSII, or BOT had been correctly diagnosed with T1DM, and one patient was treated with BOT due poor adherence.

Meanwhile, in the 13 T2DM DKA patients, the mean age was noted to be 54.7 ± 16.9 years, finding that T2DM DKA developed in both the elderly and young patients. Among them, 6 (46.1%) were unaware of their impaired glucose tolerance, 6 (46.1%) had already been diagnosed with T2DM and taking their respective medications (OHA, 2 patients; insulin injection, 1 patient; and interruption, 3 patients), and the status was unknown in the remaining patient (7.6%).

Causes of DKA

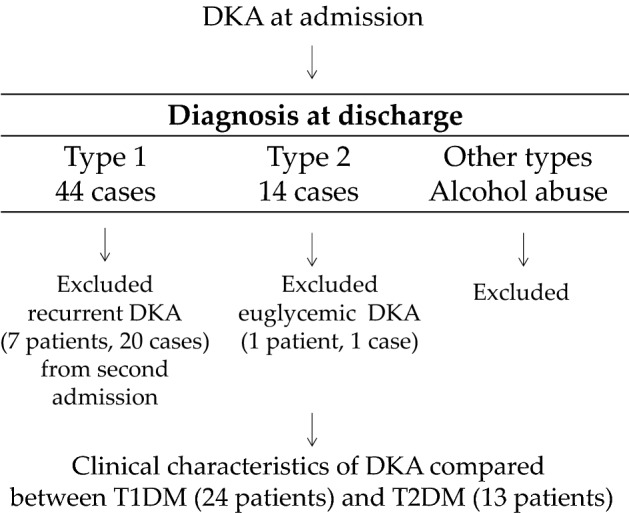

On analysis of the causes of DKA, the main factor in T1DM DKA was self-discontinuation of insulin (Fig. 2, left), the common causes of which were miscommunication with medical staff, non-adherence to treatment, and dementia or other psychiatric disorders. Other causes included the 4 newly diagnosed T1DM patients and the patient who misused CSII.

Fig. 2.

Clinical factors in the development of DKA in a T1DM (n = 24) and b T2DM (n = 13). Data are expressed as causes of DKA and number of cases (%). CSII continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, DKA diabetic ketoacidosis, HHS hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, T1DM type 1 diabetes, T2DM type 2 diabetes

On the other hand, the main causes of T2DM DKA (Fig. 2, right) were consumption of soft drinks (4 patients, 30.8%), bacterial infection (4 patients, 30.8%), and insulin secretory disorders secondary to hyperosmolar hyperglycemic states (HHS; 3 patients, 23.0%). Soft drink ketosis, in particular, is an atypical form of DKA reported in Japan [10, 11] that develops in T2DM patients with excessive sugar-containing soft drink consumption and obesity. This excessive intake of sugary drinks is considered to aggravate insulin secretion transiently, even in patients with a higher capacity for insulin secretion. Meanwhile, patients with HHS, a condition occurring commonly in older T2DM patients, were found to be relatively insulin-deficient, wherein this state often causes hormone-sensitive lipase activation and ketone body production, resulting to an overlap between DKA and HHS. In this study, the causes of HHS included drug reactions (1 case of prednisolone-induced HHS), cancer (1 case), and treatment changes (1 case). Finally, among the 4 patients with bacterial infection, 2 had urinary tract infections, 1 had cellulitis, and 1 had infective endocarditis.

As shown in Table 1, among the T2DM DKA patients, 6 (46.1%) were unaware of their impaired glucose tolerance, including all 4 soft drink ketosis patients and 2 DKA patients secondary to HHS. Meanwhile, the remaining 6 who were previously diagnosed with T2DM included all 4 bacterial infection-induced DKA patients and 1 DKA patient secondary to HHS.

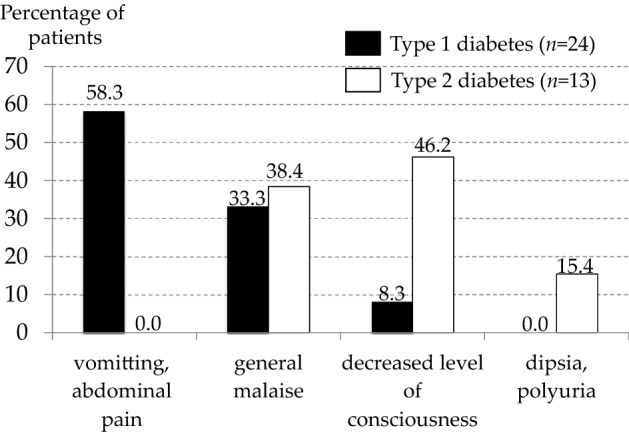

Differences in clinical presentation

Following the analysis of the characteristics and causes of DKA, we compared the main complaints of the patients in both groups (Fig. 3). In T1DM, most patients (14/24, 58.3%) presented with vomiting, followed by generalized malaise and decreased level of consciousness, whereas most T2DM patients (11/13, 84.6%) presented with decreased levels of consciousness and generalized malaise. In addition, although none of the patients complained of only abdominal pain, 2 T1DM patients presented with abdominal pain and vomiting simultaneously. Furthermore, only a few T2DM DKA patients experienced vomiting and abdominal pain. Interestingly, polydipsia and polyuria, which are typical symptoms associated with acute decompensated diabetes, were frequently observed during the clinical course of DKA, but the initial presentations in this study were predominantly gastrointestinal symptoms in T1DM patients and systemic symptoms in T2DM patients.

Fig. 3.

Main complaints in T1DM cases (n = 24) and T2DM cases (n = 13) in the emergency department. Data are expressed as percentage of cases. Black: type 1 diabetes, white: type 2 diabetes

Laboratory investigations

Blood tests revealed that plasma glucose levels, osmotic pressure, and ketone bodies were comparable between the two groups (Table 2). In contrast, serum potassium level was found to be significantly higher in T1DM DKA patients, despite showing a trend toward lower serum creatinine levels (p = 0.09). However, both HbA1c and C-reactive protein levels were significantly lower in the T1DM DKA group, with the exception of 10 T1DM DKA patients showing mildly elevated CRP levels.

Table 2.

Patients laboratory findings by diabetes type in the emergency room

| T1DM | T2DM | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 760.3 ± 339.8 | 831.8 ± 397.8 | 0.621 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 132.3 ± 9.3 | 135.5 ± 12.3 | 0.408 |

| K (mEq/L) | 5.4 ± 1.0 | 4.7 ± 1.3 | 0.042 |

| Cl (mEq/L) | 93.5 ± 8.2 | 97.2 ± 11.0 | 0.230 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 33.9 ± 19.5 | 65.6 ± 48.8 | 0.168 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 0.092 |

| BUN/creatinine | 1.51 ± 0.14 | 1.47 ± 0.19 | 0.422 |

| Plasma osmotic pressure† (mOsm/L) | 320.6 ± 27.2 | 340.5 ± 51.7 | 0.160 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 10.5 ± 13.9 | 0.004 |

| WBC (× 103/μL) | 152.6 ± 57.0 | 146.0 ± 64.3 | 0.601 |

| PH | 7.13 ± 0.10 | 7.19 ± 0.09 | 0.093 |

| Total ketone body (μmol/L) | 11,027.6 ± 3528.3 | 9413.5 ± 3682.7 | 0.193 |

| β-Hydroxybutirate (μmol/L) | 9149.4 ± 3236.6 | 7644.0 ± 3178.7 | 0.197 |

| Acetate (μmol/L) | 1905.5 ± 855.4 | 1627.8 ± 660.4 | 0.456 |

| β-Hydroxybutirate/acetate | 6.30 ± 5.88 | 4.83 ± 1.93 | 0.584 |

| HbA1c (%) | 10.5 ± 2.7 | 13.1 ± 2.0 | 0.002 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Parameters were transformed logarithmically and Student’s t test was applied

BUN blood urea nitrogen, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, CRP C-reactive protein, WBC white blood cell

†Formula: Na (mEq/L) × 2 + BUN (mg/dL)/2.8 + Glc (mg/dL)/18

Electrolyte sodium and calcium imbalances can lead to vomiting and decreased levels of consciousness; however, no significant difference was found in the sodium levels of both groups. Although serum calcium levels were measured in only a small number of patients in the emergency room, none of the patients showed any serum calcium abnormalities during hospitalization.

Next, to evaluate the ability of serum potassium levels to predict T1DM in DKA patients in the emergency room, we plotted a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) (Supplemental Figure), calculating the area under the ROC curve to be 0.72. In addition, the optical cut-off point was determined to be 5.0 mEq/mL using the Youden index (sensitivity = 66.7%, specificity = 76.9%).

Discussion

Since few reports are available on the differences in DKA based on the type of diabetes [12, 13], we investigated the differences between T1DM and T2DM in terms of the causes and clinical presentation of DKA. Our main findings were as follows. Insulin omission and new onset were the main causes of T1DM DKA, which was generally consistent with previous reports. In the T2DM DKA group, the main causes were soft drink consumption and infection, with a higher proportion of newly diagnosed patients as compared to the T1DM DKA group. Furthermore, we found that the two groups had different complaints, wherein vomiting was a characteristic symptom of T1DM, which has not been reported before.

Of the 37 patients who were emergently admitted with DKA we analyzed, 24 (64.9%) were discharged with a diagnosis of T1DM and 13 (35.1%) with T2DM. For our T2DM DKA patients, the reported range was similar to the 20%–30% of the ranges reported in the following previous studies [4, 14–16]. Although the first presentation of diabetes was recorded in 16.7% of our T1DM patients, which was generally consistent with previous findings [17, 18], this was much higher in our T2DM patients (46.1%) as compared to previous studies [13, 19]. In addition, of the total DKA patients in this study, 27.0% (10/37) were newly diagnosed with diabetes.

The main causes of T1DM DKA were insulin omission and new onset, as previously reported [18]. The most common causes of insulin omission were miscommunication with medical staff during illness, non-compliance with treatment, and psychiatric disorders, such as dementia and depression. In this study, 5 T1DM patients (20.8%) were mistakenly treated as T2DM and prescribed biphasic insulin. Of particular concerns were the lack of sufficient taught diabetes education and their immediate cessation of insulin injections. Misdiagnosis of diabetes types misdiagnosis was also one of the reported important causes of DKA [20].

An epidemiological study on childhood-onset T1DM conducted between 2005 and 2012 showed no increase in T1DM incidence [20]. Currently, advanced therapy has been considered to help improve T1DM prognosis, so with the number of elderly T1DM DKA patients expected to increase, it is necessary to develop strategies to improve adherence and prevent DKA. Our hospital has been distributing handouts to T1DM patients with information on how to manage hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and acute illness, additionally providing simple explanations for individualized management such as about corrective insulin dosing and changing an insulin infusion set for CSII-users. Moreover, the continuous glucose monitoring system [21, 22] and the closed-loop insulin delivery system [23, 24] may be new strategies to prevent DKA.

The main causes of T2DM DKA were infection and soft drink consumption, as previously reported. All T2DM DKA patients with infection had been diagnosed with T2DM in the past, whereas for all 4 soft drink ketosis patients, this was their first presentation of diabetes, which was a significant finding. The prevalence of obesity and T2DM in children and adolescents has been increasing globally, and the same trend can be seen in Japan [25]. According to an investigation of registered diabetic patients under 20 years of age, childhood-onset T2DM incidence in Japan, which was strongly related to obesity, was reported to be more frequent than that of T1DM after puberty. More importantly, youth onset T2DM poses a particular risk in diabetic complications [26, 27]. Lifestyle intervention, including reducing sugary drink ingestion, therefore remains a significant challenge in preventing T2DM or obesity among children and adolescents from acute decompensated diabetes.

Notably, more than half of the T1DM DKA patients presented with vomiting as the main complaint, whereas, most T2DM DKA patients showed decreased levels of consciousness and generalized malaise, with none of them presenting with vomiting or nausea. To the best of our knowledge, this has not been reported previously. Although vomiting and abdominal pain have been detected in many cases of DKA [28–30], little is known about the differences in symptoms between T1DM and T2DM DKA.

Ketone bodies have been reported to directly activate the vomiting center located in the medulla oblongata [31]; however, the plasma levels of ketone bodies were comparable between the two groups. Acute ketonemia in T1DM DKA after insulin omission was presumed to activate the chemoreceptor trigger zone, leading to vomiting. Those who did not present with vomiting in T1DM mainly included those who continued insulin injection irregularly due to misdiagnosis of diabetes type and consequent prescription of biphasic or basal insulin. In T2DM, DKA was caused by severe insulin resistance induced by excessive consumption of sugary drinks or bacterial infection. For this reason, ketosis progression was subacute, possibly resulting to generalized malaise or decreased level of consciousness secondary to infection or dehydration as the predominant presentation. Since T1DM accounts for more than two-thirds of all patients [4, 15], vomiting and abdominal pain may be considered as common symptoms of DKA. Furthermore, attention should be given to atypical symptoms in T2DM DKA patients.

On blood examination, serum potassium levels were higher in T1DM DKA cases, which was consistent with a previous report by Wang et al. [11]. There was also a trend for lower serum creatinine levels in T1DM, thus it was conceivable that hyperkalemia was the result of severe insulin deficiency. However, several conditions of patients can influence serum potassium levels as well, such as oral medicine, gastroenteritis, and other diseases. The results obtained so far are controversial, and further studies are warranted.

As described above, we revealed two salient differences in the clinical presentations of both diabetes types, namely vomiting and serum potassium levels. According to the guidelines, DKA treatment in T2DM is typically similar to that in T1DM; however, many previous studies have shown that their underlying pathophysiology and clinical profiles differ, such as significant insulin resistance, infection, older age, and comorbidities in T2DM patients. Balmier et al., for one, reported that hypoglycemia rate during the first 48 h was significantly higher among T1DM patients than among T2DM patients (76.9% vs. 50.0%), even though T1DM patients were treated with lower insulin doses, and reducing insulin doses in T1DM DKA patients should have helped prevent this complication [32]. Kamata et al. in particular, reported that T2DM DKA was associated with severe dehydration and hyperglycemia, and patients therefore require a higher insulin dosage and a larger fluid volume [33]. Previous studies, among those mentioned in this manuscript, have recommended that DKA treatment be based on the type of diabetes. Our findings showed that vomiting and hyperkalemia were suggestive of T1DM DKA, assisting the DKA treatment based on diabetes type at emergency room and affirming the recommendations of these previous studies.

Our findings could allow for the possibility of using vomiting and hyperkalemia as markers of T1DM in the emergency room, possibly aiding in the initial appropriate treatment based on diabetes type and allowing a better understanding of the pathophysiology of these patients.

Despite our relevant findings, this study had several limitations. Its retrospective design and basis on medical records from a single hospital were some of these significant limitations. Thus, prospective studies and multicenter trials are required to confirm these findings.

In summary, inappropriate insulin prescription remains a frequent cause of T1DM DKA. On the other hand, soft drink ketosis appears to be an important factor in the first presentation of T2DM. Regarding clinical characteristics, our findings showed that vomiting and hyperkalemia were characteristic presentations of T1DM DKA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by members of the Kobe City Medical Center West Hospital.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to the publication of this study.

Human and animal rights

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Committee on Human Experimentation (Kobe City Medical Center West Hospital, Approval No. 17–021, date of approval: February 28, 2018) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its subsequent revision.

Informed consent

Using only existing materials mentioned in this manuscript, the study was considered exempt from the need for an informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Karslioglu French E, Donihi AC, Korytkowski MT. Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome: review of acute decompensated diabetes in adult patients. BMJ. 2019;29(365):11114. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siwakoti K, Giri S, Kadaria D. Cerebral edema among adults with diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome: incidence, characteristics, and outcomes. J Diabetes. 2017;9:208–209. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai D, Mehta D, Mathias P, Menon G, Schubart UK. Health care utilization and burden of diabetic ketoacidosis in the US over the past decade: a nationwide analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1631–1638. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong VW, Juhaeri J, Mayer-Davis EJ. Trends in hospital admission for diabetic ketoacidosis in adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England, 1998–2013: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1870–1877. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1335–1343. doi: 10.2337/dc09-9032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benoit SR, Zhang Y, Geiss LS, Gregg EW, Albright A. Trends in diabetic ketoacidosis hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality - United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:362–365. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6712a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyenwe EA, Kitabchi AE. The evolution of diabetic ketoacidosis: an update of its etiology, pathogenesis and management. Metabolism. 2016;65:507–521. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawasaki E, Maruyama T, Imagawa A, Awata T, Ikegami H, Uchigata Y, Osawa H, Kawabata Y, Kobayashi T, Shimada A, Shimizu I, Takahashi K, Nagata M, Makino H, Hanafusa T. Diagnostic criteria for acute-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus (2012): report of the committee of Japan diabetes society on the research of fulminant and acute-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2014;5:115–118. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modi A, Agrawal A, Morgan F. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: a review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2017;13:315–321. doi: 10.2174/1573399812666160421121307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada K, Nonaka K. Diabetic ketoacidosis in young obese Japanese men. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:671. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.6.671a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki Y, Hamamoto Y, Kawasaki Y, Ikeda H, Honjo S, Wada Y, Koshiyama H. Japanese cases of acute onset diabetic ketosis without acidosis in the absence of glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibody. Endocrine. 2010;37:286–288. doi: 10.1007/s12020-009-9301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang ZH, Kihl-Selstam E, Eriksson JW. Ketoacidosis occurs in both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes-a population-based study from Northern Sweden. Diabet Med. 2008;25:867–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newton CA, Raskin P. Diabetic ketoacidosis in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: clinical and biochemical differences. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1925–1931. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.17.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko SH, Lee WY, Lee JH, Kwon HS, Lee JM, Kim SR, Moon SD, Song KH, Han JH, Ahn YB, Yoo SJ, Son HY. Clinical characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in Korea over the past two decades. Diabet Med. 2005;22:466–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandstaetter E, Bartal C, Sagy I, Jotkowitz A, Barski L. Recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2019;63:531–535. doi: 10.20945/2359-3997000000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee MH, Calder GL, Santamaria JD, MacIsaac RJ. Diabetic ketoacidosis in adult patients: an audit of factors influencing time to normalisation of metabolic parameters. Intern Med J. 2018;48:529–534. doi: 10.1111/imj.13735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinert LS, Scheffel RS, Severo MD, Cioffi AP, Teló GH, Boschi A, Schaan BD. Precipitating factors of diabetic ketoacidosis at a public hospital in a middle-income country. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;96:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umpierrez G, Korytkowski M. Diabetic emergencies -ketoacidosis, hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state and hypoglycaemia. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:222–232. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu XY, She DM, Wang F, Guo G, Li R, Fang P, Li L, Zhou Y, Zhang KQ, Xue Y. Clinical profiles, otcomes and risk factors among type 2 diabetic inpatients with diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state: a hospital based analysis over a 6-year period. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20:182–219. doi: 10.1186/s12902-020-00659-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bao YK, Ma J, Ganesan VC, McGill JB. Mistaken identity: missed diagnosis of Type1 diabetes in an older adult. Med Res Arch. 2019;7:1962–1966. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onda Y, Sugihara S, Ogata T, Yokoya S, Yokoyama T, Tajima N, Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) Study Group Incidence and prevalence of childhood-onset Type1 diabetes in Japan: the T1D study. Diabet Med. 2017;34:909–915. doi: 10.1111/dme.13295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tauschmann M, Hermann JM, Freiberg C, Papsch M, Thon A, Heidtmann B, Placzeck K, Agena D, Kapellen TM, Schenk B, Wolf J, Danne T, Rami-Merhar B, Holl RW, DPV Initiative Reduction in diabetic ketoacidosis and severe hypoglycemia in pediatric Type1 diabetes during the first year of continuous glucose monitoring: a multicenter analysis of 3,553 subjects from the DPV registry. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:e40–e42. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charleer S, Mathieu C, Nobels F, De Block CD, Radermecker RP, Hermans MP, Taes Y, Vercammen C, T’Sjoen G, Crenier L, Fieuws S, Keymeulen B, Gillard P, RESCUE Trial Investigators Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control, acute admissions, and quality of life: a real-world study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1224–1232. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-02498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown SA, Kovatchev BP, Raghinaru D, Lum JW, Buckingham BA, Kudva YC, Laffel LM, Levy CJ, Pinsker JE, Wadwa RP, et al. Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in Type1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1707–1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1907863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg SK, Weinzimer SA, Tamborlane WV, Buckingham BA, Bode BW, Bailey TS, Brazg RL, Ilany J, Slover RH, Anderson SM, Bergenstal RM, Grosman B, Roy A, Cordero TL, Shin J, Lee SW, Kaufman FR, Anderson SM, et al. Glucose outcomes with the in-home use of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2017;19:155–163. doi: 10.1089/dia.2016.0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuura N, Amemiya S, Sugihara S, Urakami T, Kikuchi N, Kato H, Yodo Y, Study Group of the Pediatric Clinical Trial of Metformin in Japan Metformin monotherapy in children and adolescents with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japan. Diabetol Int. 2019;10:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s13340-018-0361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spurr S, Bally J, Bullin C, Allan D, McNair E. The prevalence of undiagnosed prediabetes/type 2 diabetes, prehypertension/hypertension and obesity among ethnic groups of adolescents in Western Canada. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:31. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-1924-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middleton TL, Constantino MI, Molyneaux L, D’Souza M, Twigg SM, Wu T, Yue DK, Zoungas S, Wong J. Young- onset Type 2 diabetes and younger current age: increased susceptibility to retinopathy in contrast to other complications. Diabet Med. 2020;37:991–999. doi: 10.1111/dme.14238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan H, Zhou Y, Yu Y. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in Chinese adults and adolescents—a teaching hospital-based analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alourfi Z, Homsi H. Precipitating factors, outcomes, and recurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis at a university hospital in Damascus. Avicenna J Med. 2015;5:11–15. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.148503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahuja W, Kumar N, Kumar S, Rizwan A. Precipitating Risk Factors, clinical presentation, and outcome of diabetic ketoacidosis in patients with Type 1 diabetes. Cureus. 2019;11:e4789. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canziani BC, Uestuener P, Fossali EF, Lava SAG, Bianchetti MG, Agostoni C, Milani GP. Clinical practice: nausea and vomiting in acute gastroenteritis: physiopathology and management. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-3006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamata Y, Takano K, Kishihara E, Watanabe M, Ichikawa R, Shichiri M. Distinct clinical characteristics and therapeutic modalities for diabetic ketoacidosis in Type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complic. 2017;31:468–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balmier A, Dib F, Serret-Larmande A, De Montmollin E, Pouyet V, Sztrymf B, Megarbane B, Thiagarajah A, Dreyfuss D, Ricard JD, Roux D. Initial management of diabetic ketoacidosis and prognosis according to diabetes type: a French multicentre observational retrospective study. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9:91. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0567-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.