Abstract

Aim

To investigate long-term effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) on anthropometric and metabolic factors in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

Patients and Methods

This is a retrospective observation study. Forty-six outpatients with T2DM (32 men and 14 women, 51 ± 13 years old, BMI 27.9 ± 4.8, means ± S.D.) who had been treated by SGLT2i for 2 years were selected and their metabolic and anthropometric data were retrieved from medical records retrospectively. Regular instruction for diet and exercise had been performed throughout the administration of SGLT2i in outpatient clinic basis.

Results

By the administration of SGLT2i for 2 years, body weight and body fat amount were significantly reduced (P < 0.0001) in spite of no change in skeletal muscle mass. HbA1c (P < 0.0001), liver function and lipid profile (P < 0.01) were ameliorated and eGFR was reduced significantly (P < 0.0001). It is of note that the reduction of body weight was strongly correlated to that of body fat (r = 0.951, P < 0.0001) with no correlation to the change of skeletal muscle mass. The reduction of HbA1c was strongly correlated to the baseline HbA1c (r = − 0.922, P < 0.0001) and modestly correlated to the baseline eGFR (r = − 0.449, P < 0.01). Multivariate analysis revealed a weak relationship between the amelioration of HbA1c and the reduction of body weight.

Conclusion

SGLT2i can effectively reduce body weight and body fat mass independent of the blood glucose improvement or the renal function. Under the periodical instruction for nutrition and exercise this oral hypoglycemic agent can be safely administered for a long term without a risk for sarcopenia.

Keywords: SGLT2 inhibitor, Long-term administration, Weight reduction, Body fat mass, HbA1c

Introduction

The number of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) has been increasing for the past half century and has been reported to finally reach 10 million in 2016 by Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan. Body mass index (BMI) in Japanese T2DM patients is also increasing and has reached 25 in 2013 [1], which is the cut-off value for the determination of obesity in Japan. In particular, visceral fat accumulation is correlated to the derangement of metabolic factors [2] as well as the progression of cardiovascular disease [3]. As the treatment of T2DM patients, especially obese patients, diet and exercise are the two essential therapeutic strategies to maintain an appropriate glycemic control and body weight. However, in clinical practice, most patients with diabetes feel the current therapeutic strategy to be a burden or distress, especially continuing diet and exercise therapy for a long period [4]. It has been reported that a considerable number of patients did not meet the target for hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) less than 7% which is a goal for appropriate glycemic control proposed by the Japan Diabetes Society [5], being associated with a higher BMI and waist circumference [6].

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) was first approved in 2014 in Japan. SGLT2i blocks SGLT2 located in the proximal tubules of the kidney and enhances the excretion of glucose into urine, thus contributes to the amelioration of blood glucose levels as well as the reduction of body weight. Because its glucose-lowering effect is not operated by either insulin secretion or insulin sensitivity, the concern for hypoglycemia is scarce by a sole administration of this medication for the treatment of T2DM. It has been reported that SGLT2i reduces body weight, predominantly by reducing fat mass composed of either visceral or subcutaneous adipose tissue in T2DM patients [7]. However, chronic glycosuria causes an adaptive increase in energy intake, which may spoil weight reduction based on energy loss excreted into urine [8]. Thus, long-term effectiveness and safety of this medication have not been fully elucidated yet, including concerns for dehydration or sarcopenia in elderly patients with diabetes. The aim of the present study is to evaluate effects of 2-years administration of SGLT2i on metabolic parameters or anthropometric factors as well as safety concerns under the appropriate guidance by healthcare practitioners in Japanese patients with T2DM.

Subjects and methods

Study population and protocol

This is a retrospective, single-center and single-arm clinical study. Outpatients with T2DM who had been treated by any SGLT2i for at least 2 years in Public Yame General Hospital were picked up referring to their medical records between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2017. Patients with excessive alcohol consumption (more than 120 g of ethanol per day), severe liver dysfunction (viral hepatitis or liver cirrhosis), renal dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtration rate: eGFR less than 60), known malignant disease and chronic inflammatory disease (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis) were excluded from the study. Finally, 46 outpatients (32 men and 14 women, 51 ± 13 years old, BMI 27.9 ± 4.8, means ± S.D.) who had fulfilled metabolic and anthropometric data before and after 2-year treatment of SGLT2i were recruited and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The sample size of 46 has been proved to be sufficient in the present study after the calculation using G*Power Version 3.1.9.4. asαerror probability 0.05 and power (1 − β error probability) 0.8.

SGLT2 prescribed per day were as follows: Ipragliflozin 50 mg in 8 patients, Empagliflozin 10 mg in 1 patient, Canagliflozin 100 mg in 11 patients, Dapagliflozin 5 mg in 9 patients, Tofogliflozin 20 mg in 8 patients and Luseogliflozin 2.5 mg in 9 patients. The dose of SGLT2i was fixed throughout 2-year treatment period. Forty-one patients had been treated by biguanide, 26 patients by DPP-4 inhibitor and 16 patients by sulfonylurea, 4 patients by glinide, 1 patient by α-glucosidase inhibitor, 7 patients by GLP-1 analogue and 7 patients by insulin (6 by intensive insulin therapy and one by basal insulin only). The dose of these oral hypoglycemic agents was titrated or ceased to maintain an appropriate HbA1c level less than 7% without hypoglycemia. No additional anti-diabetic treatment was initiated for the entire experimental period.

For all patients, a nutrition counseling by dietitians was performed periodically (at least every 3 months) and aerobic exercise was instructed using pedometers to walk at least 5000 steps per day. Resistance training of low impact, such as half-squat, push-up and sit-up (ten times each, three sets per day), was instructed by a physician or medical staff before or during examination using commercially available leaflets. If possible, standing on one leg and knee extension for 30 s (three sets per day) were further instructed.

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of Kurume University School of Medicine and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki 2013. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kurume University School of Medicine (approval number 18247).

Measurements

Metabolic and anthropometric factors were measured at least twice, before the initiation and after 2-year administration of SGLT2i, except for eGFR which was measured at every visiting time. Changes in each metabolic or anthropometric factors were calculated by the subtraction shown below and expressed as Δ.

Metabolic parameters included HbA1c, low- and high-density lipoprotein cholesterols (LDL-C and HDL-C), triglyceride (TG), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr) and uric acid (UA) levels, all of which were measured according to the standard procedures in the early morning after an 8-h fast. eGFR was calculated according to the revised equations for Japanese people [9]. Body weight, the amounts of skeletal muscle and body fat were measured by a body composition analyzer (InBody 720, Tokyo, Japan) using the bio-impedance method. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg)/[height (m)]2.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means ± S.D. Correlations on Δ(body weight) and Δ(HbA1c) as outcome variables with other parameters as predictive variables were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient for univariate analysis and multiple regression analysis for multivariate analysis. Changes in metabolic and anthropometric parameters before and after 2-year administration of SGLT2i were analyzed using paired t test. A change in eGFR throughout 2-year administration of SGLT2i was analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP ® 15 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). P values less than 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Results

Changes in metabolic and anthropometric parameters (Table 1)

Table 1.

Changes in parameters at baseline and after 2 years of treatment

| Baseline | 2 years | Δ(value) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight | 76.4 ± 15.3 | 72.7 ± 14.3 | − 3.9 ± 4.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Body mass Index (kg/m2) | 27.9 ± 4.8 | 26.5 ± 4.4 | − 1.5 ± 1.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Skeletal muscle amount (kg) | 27.8 ± 5.2 | 27.6 ± 5.2 | − 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.0936 |

| Skeletal muscle percentage (%) | 36.8 ± 5.4 | 38.3 ± 5.4 | 1.6 ± 2.3 | < 0.0001 |

| Body fat amount (kg) | 25.9 ± 10.8 | 22.5 ± 9.5 | − 3.5 ± 4.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Body fat percentage (%) | 33.0 ± 9.3 | 30.2 ± 9.1 | − 3.0 ± 4.2 | < 0.0001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.56 ± 2.01 | 6.66 ± 0.83 | − 2.0 ± 2.1 | < 0.0001 |

| AST (U/L) | 33.6 ± 24.0 | 23.8 ± 9.67 | − 10.1 ± 19.6 | 0.0029 |

| ALT (U/L) | 47.0 ± 32.5 | 29.2 ± 18.1 | − 18.5 ± 28.4 | 0.0003 |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 63.7 ± 76.1 | 38.2 ± 36.5 | − 26.2 ± 50.1 | 0.0024 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 123.4 ± 38.2 | 104.0 ± 21.9 | − 20.5 ± 36.3 | 0.0017 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 47.5 ± 16.8 | 49.4 ± 13.0 | 1.9 ± 13.7 | 0.3634 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 229.9 ± 214.4 | 132.0 ± 69.0 | − 100.2 ± 184.4 | 0.0016 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 13.6 ± 3.1 | 14.7 ± 3.9 | 1.3 ± 3.5 | 0.0666 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.68 ± 0.14 | 0.73 ± 0.15 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 92.5 ± 18.6 | 85.2 ± 16.1 | − 6.0 ± 10.7 | < 0.0001 |

| UA (mg/dL) | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | − 0.3 ± 1.0 | 0.1575 |

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Paired t test

HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, AST aspartate amino transferase, ALT alanine amino transferase, γ-GTP γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglycerides, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Cr creatinine, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, UA uric acid

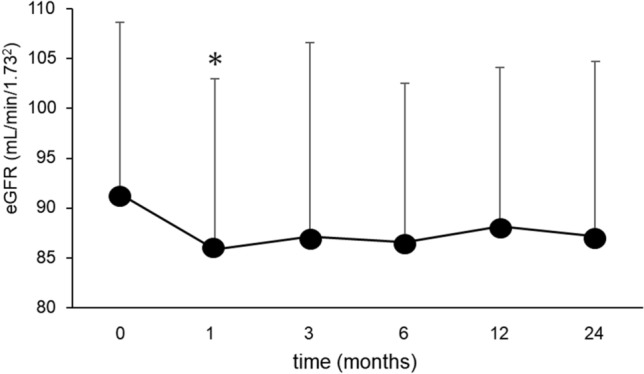

By the administration of SGLT2i for 2 years, body weight and BMI were markedly and significantly reduced by 3.7 kg and 1.4, respectively. The amount of body fat and its percentage of body weight were significantly reduced while the amount of skeletal muscle did not change and the skeletal muscle percentage were rather increased after 2-year treatment of this medication. Metabolic parameters including HbA1c, liver function and lipid profile, such as LDL-C and TG, were all decreased significantly. eGFR was significantly decreased reflecting a significant increase of serum Cr level after 2 years of treatment. Examined in detail, eGFR significantly declined 1 month after the initiation of SGLT2i, then continued non-significant decrease compared to the baseline value throughout 2 years (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Change of eGFR for 2 years after the initiation of SGLT2 inhibitor. Data are presented as means and S.D. *P < 0.05 vs. the baseline value

Correlations between Δ(body weight) and each parameter

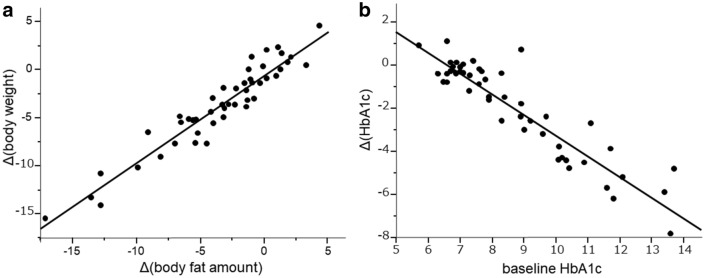

In the univariate analysis, the reduction of body weight for 2 years was strongly correlated to the reduction of body fat amount for this period (r = 0.951, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2a), and moderately correlated to the reduction of HbA1c, ALT, γ-GTP and TG. The higher level of body weight, BMI, body fat amount and HbA1c before the initiation of SGLT2i were significant negative predictive variables to Δ(body weight). Δ(body weight) tended to be negatively correlated to eGFR before the treatment, but the relationship was not significant (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Correlations between Δ(body weight) and Δ(body fat amount) (a), and between Δ(HbA1c) and baseline HbA1c (b)

Table 2.

Univariate analysis on Δ(body weight) as an outcome variable

| r value | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.277 | 0.0646 |

| Body weight | − 0.358 | 0.0156 |

| Body mass index | − 0.406 | 0.0057 |

| Body fat amount | − 0.48 | 0.0009 |

| Skeletal muscle amount | − 0.047 | 0.7606 |

| Δbody fat amount | 0.951 | < 0.0001 |

| Δskeletal muscle amount | 0.09 | 0.9547 |

| eGFR | − 0.311 | 0.0574 |

| HbA1c | − 0.379 | 0.0102 |

| ΔHbA1c | 0.43 | 0.0032 |

| ΔAST | 0.209 | 0.1952 |

| ΔALT | 0.387 | 0.0136 |

| Δγ-GTP | 0.421 | 0.0068 |

| ΔLDL-C | 0.105 | 0.5171 |

| ΔlogTG | 0.4875 | 0.0014 |

| ΔHDL-C | − 0.229 | 0.1556 |

Pearson’s correlation coefficient

eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, AST aspartate amino transferase, ALT alanine amino transferase, γ-GTP γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglyceride, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

In the multivariate analysis, Δ(body weight) was almost perfectly explained by Δ(body fat amount), showing a quite high value of its standard β (1.067). On the other hand, Δ(HbA1c) was moderately correlated to Δ(body weight) in this model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis on Δ(body weight) as an outcome variable

| Estimate | S.E | Standard β | t value | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | − 0.894 | 0.323 | 0 | − 2.77 | 0.0088 |

| ΔBody fat mass | 1.048 | 0.066 | 1.067 | 15.95 | < 0.0001 |

| ΔHbA1c | − 0.273 | 0.118 | − 0.13 | − 2.32 | 0.0263 |

| ΔlogTG | − 1.618 | 1.179 | − 0.086 | − 1.48 | 0.1471 |

Multiple regression analysis. R2 = 0.921 for this model

S.E. standard error, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, TG triglyceride

Correlations between Δ(HbA1c) and each parameter

In the univariate analysis, the decrease of HbA1c on an outcome variable was much strongly correlated to the higher HbA1c value (r = 0.922, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2b) and moderately to the younger age and the higher eGFR before the initiation of SGLT2i. Δ(HbA1c) was also significantly correlated to Δ(body weight), Δ(body fat mass), Δ(skeletal muscle mass) and Δ(LDL-C) for the administration of SGLT2i (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis on Δ(HbA1c) as an outcome variable

| r value | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.395 | 0.0073 |

| Body weight | − 0.114 | 0.4563 |

| Body mass index | − 0.109 | 0.4765 |

| Body fat mass | − 0.11 | 0.4728 |

| Skeletal muscle mass | − 0.086 | 0.5733 |

| Δbody weight | 0.43 | 0.0032 |

| Δbody fat mass | 0.538 | 0.0001 |

| Δskeletal muscle mass | − 0.361 | 0.0149 |

| HbA1c | − 0.922 | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR | − 0.449 | 0.0047 |

| ΔAST | 0.077 | 0.6361 |

| ΔALT | 0.279 | 0.0811 |

| Δγ-GTP | 0.291 | 0.0685 |

| ΔLDL-C | 0.353 | 0.0257 |

| ΔlogTG | 0.107 | 0.5091 |

| ΔHDL-C | 0.041 | 0.8014 |

*Pearson’s correlation coefficient

eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, AST aspartate amino transferase, ALT alanine amino transferase, γ-GTP γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglycerides, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

In the multivariate analysis, the strong contribution of HbA1c before the initiation of SGLT2i could explain the decrease of HbA1c by 86% (r2 = 0.859) with no contribution of other variables (Table 5, Model 1). To evaluate more precise contribution of other variables, we constructed another model without the initial HbA1c (Table 5, Model 2). In this model, the higher eGFR and the decrease of body weight for 2 years were selected as significant predictive variables for Δ(HbA1c) although their contribution (r2 = 0.336) was much lower than the initial HbA1c value alone.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis on Δ(HbA1c) as an outcome variable

| Estimate | S.E | Standard β | t value | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||||

| Intercept | 7.146 | 0.807 | 0 | 8.86 | < 0.0001 |

| HbA1c | − 0.939 | 0.085 | − 0.864 | − 11.08 | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR | − 0.009 | 0.008 | − 0.091 | − 1.25 | 0.2193 |

| Δ(body weight) | 0.041 | 0.033 | 0.088 | 1.23 | 0.229 |

| Δ(LDL-C) | − 0.002 | 0.004 | − 0.04 | − 0.57 | 0.572 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Intercept | 2.011 | 1.414 | 0 | 1.42 | 0.1641 |

| eGFR | − 0.033 | 0.016 | − 0.314 | − 2.11 | 0.0424 |

| Δ(body weight) | 0.145 | 0.016 | 0.310 | 2.11 | 0.0427 |

| Δ(LDL-C) | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.205 | 1.44 | 0.1591 |

Multiple regression analysis. r2 = 0.859 for model 1 and 0.336 for model 2

S.E. standard error, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Safety concerns

Throughout 2 years of administration of SGLT2i, no severe adverse event to oblige to cease the administration of SGLT2i occurred. Three patients who had been treated with insulin complained of hypoglycemia and their symptoms disappeared after the adjustment of their insulin dosage. Seventeen patients complained of polyuria or pollakisuria, 1 patient of thirst and 2 patients of constipation, all of which did not affect the continuation of SGLT2i. No ketosis, dehydration or skin eruption occurred in any patient.

Discussion

Results obtained in this retrospective clinical study were as follows. First, 2-year administration of SGLT2i brought about marked reduction of body weight, most of which could be attributed to the reduction of body fat amount. The amount of skeletal muscle was not affected by SGLT2i administration at all. Second, metabolic parameters including HbA1c, liver function and lipid profiles were markedly improved in spite of the significant decline of eGFR by the administration of SGLT2i. Third, the reduction of body weight was modestly related to the improvement of HbA1c, and vice versa. Finally, glucose-lowering effect of SGLT2i was dependent on renal function such as eGFR, although effect on weight reduction of this medication was not related to renal function at all.

Because glucose-lowering mechanisms of SGLT2i are largely attributed to the increase of glucose excretion into urine and the loss of calorie, beneficial effects of this class of medications on body weight, body fat and waist circumference are promising and have been reported so far [7, 10]. On the other hand, loss of body muscle mass is an important component of sarcopenia, leading to frailty and mortality [11]. Regarding SGLT2i-induced weight reduction, sarcopenia has been raised as a clinical concern, especially in elderly and lean patients and the decrease of lean body mass has been reported together with the decrease of body weight and body fat mass [7, 10]. Indeed, reduced lean body mass commonly occurs with weight reduction after various interventions, such as bariatric surgery [12], a very low-calorie diet [13] and the treatment by a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist [14], suggesting that the muscle mass reduction accompanied with weight reduction is attributable to reduced weight-bearing effects, especially in the antigravity muscles [15].

Conversely, some previous reports indicated that 6-month treatment of SGLT2i significantly improved glycemic control and reduced body weight without reducing muscle mass in T2DM patients [15, 16]. Thus, the long-term effect of SGLT2i administration on body components, especially on lean body mass, has not been completely elucidated so far. In the present study, 2-year administration of SGLT2i brought about a marked reduction of body weight, almost all of which could be attributable to the reduction of body fat mass, and no effect on skeletal muscle mass was observed in our patients with T2DM. These results are comparable between subgroups of gender (male and female), age (over and less than 60 years) and BMI (over and less than 25). One possible explanation for the maintenance of lean body mass was that the instruction for nutrition and exercise including resistance training had been performed periodically in all participants and could help them with preserving skeletal muscle amount. In this aspect, the guidance for medical treatment, such as diet or exercise, is quite essential especially when using SGLT2i for the treatment of T2DM.

Metabolic parameters, such as HbA1c, liver function and lipid profile, were markedly improved along with 2-year administration of SGLT2i in line with previous reports [17, 18]. The decline of eGFR is in accordance with the results reported in clinical studies including large scale cardiovascular outcome trials, such as EMPAREG-OUTCOME Trial [19] or CREDENCE Trial [20], known as ‘initial dip’. In the present study, the initial dip was clearly demonstrated in real-world setting. As a result of multivariate analysis, the decrease of HbA1c by SGLT2i administration was most explained by the baseline value of HbA1c. In the second model without the baseline HbA1c, an effect on HbA1c of this medication was modestly related to the baseline eGFR. Again, these results are comparable between subgroups of gender (male and female), age (over and less than 60 years) and BMI (over and less than 25). Taking the glucose-lowering mechanism such as an enhancement of urinary glucose excretion by SGLT2i into account, the lower renal function could be a negative factor for the decrease of HbA1c level in line with previous reports [21, 22]. In fact, urinary glucose excretion was gradually decrease in parallel with the decline of eGFR after a single and long-term administration of tofogliflozin in Japanese patients with type 2 DM [23].

It is of interest that a significant weight reduction was observed even in patients with moderate renal impairment (eGFR 30≦ and < 45) in their reports [22, 23]. This discrepancy between the effect on the body weight reduction and the improvement of blood glucose level under renal dysfunction is also observed in other previous reports using variety of SGLT2 inhibitors [24–27], although the reason remains unclear. In animal model of obesity, the administration of SGLT2i accelerated lipolysis in the white adipose tissue and hepatic β-oxidation [28], and increase energy expenditure, heat production, the expression of uncoupling protein 1 in the brown fat [29]. These anti-obesity effects of SGLT2i could be involved in fat utilization and weight reduction independent of renal glucose excretion. In our patients with normal renal function, these two major effects of SGLT2i, such as lowering glucose level and weight reduction, were not strongly related to each other, and weight reduction was not affected by renal function at all. In other words, beneficial effects on anthropometric factors could be expected even in patients with impaired renal function to whom glucose-lowering effect is not promising. Further studies are warranted to clarify this unsolved issue.

There are some limitations in the present study. The body composition was measured using bio-impedance method, which could be affected by water depletion due to osmotic diuresis along with the administration of SGLT2i. However, it has been reported that water depletion by SGLT2i was largely attenuated by 3 months and could contribute to initial phase of body weight reduction [30], while long-term weight reduction is attributable to loss of fat mass [31]. This is a retrospective observation study and the number of participants is small. However, these are real-world data which are better fit to needs in clinical practice. Results obtained in the present study should be confirmed in a future study of prospective design. SGLT2i administered in this study are composed of 6 brands which can be prescribed in Japan. However, results in the present study could better reflect the clinical state of affairs and could suggest class effects of SGLT2i.

In conclusion, SGLT2i can effectively reduce body weight and body fat mass independent of the blood glucose improvement or the renal function. Under the periodical instruction for nutrition and exercise, this oral hypoglycemic agent can be safely administered for a long-term without a risk for sarcopenia. Future prospective studies are necessary to confirm these results obtained in a real-world manner.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study Group.http://jddm.jp/data/index-2019/.

- 2.Tajiri Y, Takei R, Mimura K, et al. Attenuated metabolic effect of waist measurement in Japanese female patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;82:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thalmann S, Meier CA. Local adipose tissue depots as cardiovascular risk factors. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:690–701. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welch GW, Jacobson AM, Polonsky WH. The problem areas in diabetes scale. An evaluation of its clinical utility. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:760–766. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guideline Committee of the Japan Diabetes Society. Treatment guide for diabetes 2013. Japan Diabetes Society.

- 6.Hu H, Hori A, Nishiura C, et al. Hba1c, blood pressure, and lipid control in people with diabetes: Japan Epidemiology Collaboration on Occupational Health Study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0159071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolinder J, Ljunggren O, Kullberg J, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on body weight, total fat mass, and regional adipose tissue distribution in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with inadequate glycemic control on metformin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1020–1031. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrannini G, Hach T, Crowe S, et al. Energy balance after sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1730–1735. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:982–992. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohta A, Kato H, Ishii S, et al. Ipragliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor, reduces intrahepatic lipid content and abdominal visceral fat volume in patients with type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:1433–1438. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1363888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bianchi L, Volpato S. Muscle dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: a major threat to patient's mobility and independence. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53:879–889. doi: 10.1007/s00592-016-0880-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carey DG, Pliego GJ, Raymond RL. Body composition and metabolic changes following bariatric surgery: effects on fat mass, lean mass and basal metabolic rate: six months to one-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1602–1608. doi: 10.1381/096089206779319347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Arbelaez D, Bellido D, Castro AI, et al. Body composition changes after very-low-calorie ketogenic diet in obesity evaluated by 3 standardized methods. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:488–498. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jendle J, Nauck MA, Matthews DR, et al. Weight loss with liraglutide, a once-daily human glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue for type 2 diabetes treatment as monotherapy or added to metformin, is primarily as a result of a reduction in fat tissue. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:1163–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue H, Morino K, Ugi S, et al. Ipragliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, reduces bodyweight and fat mass, but not muscle mass, in Japanese type 2 diabetes patients treated with insulin: a randomized clinical trial. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10:1012–1021. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiyama S, Jinnouchi H, Kurinami N, et al. Dapagliflozin reduces fat mass without affecting muscle mass in type 2 diabetes. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25:467–476. doi: 10.5551/jat.40873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura I, Maegawa H, Tobe K, et al. Safety and effectiveness of Ipragliflozin for type 2 diabetes in Japan: 12-month interim results of the STELLA-LONG TERM post-marketing surveillance study. Adv Ther. 2019;36:923–949. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-0895-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leiter LA, Forst T, Polidori D, et al. Effect of canagliflozin on liver function tests in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2016;42:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:323–334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2295–2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.List JF, Woo V, Morales E, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransport inhibition with dapagliflozin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:650–657. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohan DE, Fioretto P, Tang W, et al. Long-term study of patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment shows that dapagliflozin reduces weight and blood pressure but does not improve glycemic control. Kidney Int. 2014;85:962–971. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikeda S, Takano Y, Schwab D, et al. Effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tofogliflozin (A SELECTIVE SGLT2 inhibitor) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2019;69:314–322. doi: 10.1055/a-0662-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yale JF, Bakris G, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin in subjects with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:463–473. doi: 10.1111/dom.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnett AH, Mithal A, Manassie J, et al. Efficacy and safety of empagliflozin added to existing antidiabetes treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:369–384. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashiwagi A, Takahashi H, Ishikawa H, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on long-term efficacy and safety of ipragliflozin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and renal impairment: results of the long-term ASP1941 safety evaluation in patients with type 2 diabetes with renal impairment (LANTERN) study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:152–160. doi: 10.1111/dom.12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haneda M, Seino Y, Inagaki N, et al. Influence of renal function on the 52-week efficacy and safety of the sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor Luseogliflozin in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2016;38:66–88. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obata A, Kubota N, Kubota T, et al. Tofogliflozin improves insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and accelerates lipolysis in adipose tissue in male mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157:1029–1042. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu L, Nagata N, Nagashimada M, et al. SGLT2 inhibition by empagliflozin promotes fat utilization and browning and attenuates inflammation and insulin resistance by polarizing M2 macrophages in diet-induced obese mice. EBioMedicine. 2017;20:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sha S, Polidori D, Heise T, et al. Effect of the sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor canagliflozin on plasma volume in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:1087–1095. doi: 10.1111/dom.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almeida JFQ, Shults N, de Souza AMA, et al. Short-term very low caloric intake causes endothelial dysfunction and increased susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias and pathology in male rats. Exp Physiol. 2020;105:1172–1184. doi: 10.1113/EP088434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]