Abstract

Background

Ulna shortening osteotomy (USO) for ulnar impaction syndrome (UIS) aims to improve pain and function by unloading the ulnar carpus. Previous studies often lack validated patient-reported outcomes or have small sample sizes. The primary objective of this study was to investigate patient-reported pain and hand function at 12 months after USO for UIS. Secondary objectives were to investigate the active range of motion, grip strength, complications, and whether outcomes differed based on etiology.

Materials and methods

We report on 106 patients with UIS who received USO between 2012 and 2019. In 44 of these patients, USO was performed secondary to distal radius fracture. Pain and function were measured with the Patient Rated Wrist/Hand Evaluation (PRWHE) before surgery and at 3 and 12 months after surgery. Active range of motion and grip strength were measured before surgery and at 3 and 12 months after surgery. Complications were scored using the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement Complications in Hand and Wrist conditions (ICHAW) tool.

Results

The PRWHE total score improved from a mean of 64 (SD = 18) before surgery to 40 (22) at 3 months and 32 (23) at 12 months after surgery (P < 0.001; effect size Cohen’s d = −1.4). There was no difference in the improvement in PRWHE total score (P = 0.99) based on etiology. Also, no clinically relevant changes in the active range of motion were measured. Independent of etiology, mean grip strength improved from 24 (11) before surgery to 30 (12) at 12 months (P = 0.001). Sixty-four percent of patients experienced at least one complication, ranging from minor to severe. Of the 80 complications in total, 50 patients (47%) had complaints of hardware irritation, of which 34 (32%) had their hardware removed. Six patients (6%) needed refixation because of nonunion.

Conclusion

We found beneficial outcomes in patients with UIS that underwent USO, although there was a large variance in the outcome and a relatively high number of complications (which includes plate removals). Results of this study may be used in preoperative counseling and shared decision-making when considering USO.

Level of evidence

Therapeutic III.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s10195-021-00621-8.

Keywords: Ulna shortening osteotomy, Ulnar impaction syndrome, DRUJ, DRF, PROM

Introduction

Ulnar impaction syndrome (UIS) is a condition at the ulnar side of the wrist that occurs because of continuous or intermittent chronic excessive loading across the ulnocarpal joint [1]. It occurs mainly in patients with positive ulnar variance. Palmer showed that an increase of the ulnar length by 2.5 mm increases the ulnar load by 42% [2]. Patients with UIS may suffer from symptoms such as ulnar-sided wrist pain, decreased range of motion, impaired grip strength, and limitations in daily living [1, 3]. Most patients with UIS start with nonoperative management such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), orthoses, corticoid injections, and hand therapy. When nonoperative management is insufficiently effective, surgical treatment can be considered.

Ulna shortening osteotomy (USO) aims to decompress the ulnar load and is a frequently used surgical treatment for patients with UIS [4, 5]. However, only a few studies with a low sample size of 10–20 patients have evaluated the effectiveness of USO using validated and reliable patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [6–9]. More studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate the results of these studies. Furthermore, the influence of UIS etiology (e.g., idiopathic UIS versus UIS secondary to distal radius fracture) on treatment outcomes is unclear.

Previous studies on USO also described the complications following USO [10–12], including nonunion or the need for plate removal due to irritation. Chan et al. [10] summarized the prevalence of complications across studies and found large variations, e.g., plate removal ranged from 0% to 45%. Furthermore, they compared their patients with previous literature and found higher complication rates, suggesting that complications after USO may not be systematically registered using a standardized tool such as the recently developed International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement Complications in Hand and Wrist conditions (ICHAW).

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the patient-reported pain and hand function at 12 months after USO for UIS. Secondary objectives were to investigate the active range of motion, grip strength, complications, and whether outcomes differed based on etiology.

Patients and methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a study involving prospectively gathered data on a consecutive cohort of patients that underwent USO between January 2012 and October 2019 at Xpert Clinics, The Netherlands. All hand surgeons at our institution are certified by the Federation of European Societies for Surgery of the Hand and over 150 hand therapists.

All patients who underwent USO were invited to be part of a routine outcome measurement system after their first consultation with a hand surgeon. Upon agreement, they received secure web-based questionnaires before and at 3 and 12 months after surgery using GemsTracker [13]. The exact research setting of our study group has been reported previously [14].

We report this study using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [15]. The Ethics Committee of the Erasmus University Medical Centre approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent for their data to be anonymously used in this study.

Participants

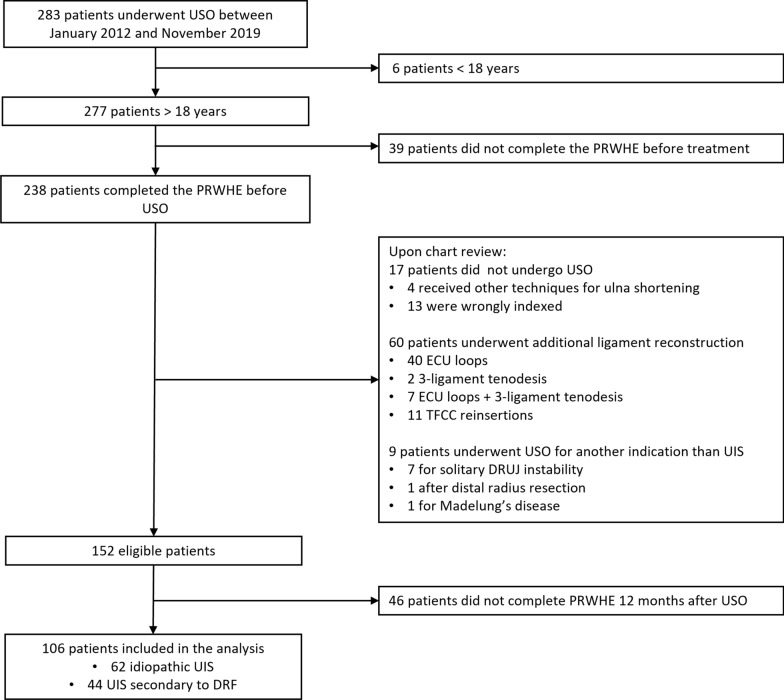

A total of 283 patients underwent ulna shortening osteotomy during the study period. We excluded 6 patients that were younger than 18 years and 39 patients who did not complete the questionnaires before surgery. We reviewed electronic patient records of the remaining 238 patients to confirm that USO was performed for UIS, as USO may also be used for other indications. To be classified as UIS, at least one of the following criteria needed to be met: (1) the surgeons explicitly diagnosed the patients with UIS in the electronic patient records; (2) wrist arthroscopy showed signs of Palmer type 2 lesions, such as Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex (TFCC) degeneration and lunate chondropathy, [16]; (3) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed signs of focal abnormal signal intensity in the lunate, triquetrum, and ulnar head [17]; (4) there was evident ulnar positive variance on standard posterior–anterior wrist radiographs in a neutral position [18]. This definition excluded patients that underwent USO for other indications, such as solitary distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) instability or Madelung’s disease. Patients who underwent simultaneous ligament reconstruction for instability [extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) loop, 3-ligament tenodesis, and TFCC reinsertion] were also excluded. This left 155 patients, of which we included 106 patients who completed all questionnaires after 12 months. Furthermore, we classified patients as having UIS secondary to distal radius fracture malunion or idiopathic UIS. The flowchart of the patient inclusion is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study. USO ulna shortening osteotomy, PRWHE Patient Rated Wrist/(Hand) Questionnaire, ECU extensor carpi ulnaris, TFCC triangular fibrocartilage complex, DRUJ distal radioulnar joint, DRF distal radius fracture

Surgical procedure and rehabilitation

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia and/or a regional axillary or supraclavicular block by 13 hand surgeons. A longitudinal incision was made on the ulnar surface and the ulna was exposed between the flexor carpi ulnaris and extensor carpi ulnaris. Care was taken not to damage the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve. The osteotomy was performed at the level of the diaphysis using a freehand cut or an external cutting device based on the surgeon’s preference, and the ulna was shortened by several millimeters, depending on the amount of preoperative radioulnar variance. The ulna was fixated using a plate on the volar or dorsal surface on the ulna based on the surgeon’s preference (n = 55 Acumed, Hillsboro, Oregon, USA; n = 47 AO, Davos, Switzerland, n = 1 Recos KLS Martin, Tuttlingen, Germany, n = 1 Trimed, Santa Clarita, California, USA, n = 1 Zimmer Biomet, Dordrecht, the Netherlands, n = 1 Medartis, Basel, Switzerland). The skin was closed with Monocryl or Prolene (Ethicon). The experience of the surgeon was defined following the classification by Tang and Giddins [19].

The routine postoperative immobilization protocol consisted of plaster cast (including the elbow) immobilization for 10–12 days (since 2015 this was reduced to 3–5 days) followed by thermoplastic orthosis until 6 weeks postoperatively. Wrist flexion/extension exercises were initiated 2 weeks postoperatively. Pronation/supination and strengthening exercises were initiated at 6 weeks postoperatively. All patients were encouraged to follow an extensive rehabilitation program including hand therapy exercises. The entire postoperative protocol is shown in the additional file 1: Table S1. Our center for hand surgery and therapy is fully integrated and postoperative hand therapy was closely monitored. Standard radiographs were taken at 3 and 12 months postoperatively to assess bony union, and additional radiographs were made on indication (e.g., in case of delayed union, nonunion, or trauma).

Implant removal is not routinely performed in the Netherlands but may be indicated on clinician-based arguments or patient-based symptoms [20]. Patient-based symptoms are considered a valid reason for hardware removal [21]. Plate removal was considered when patients experienced irritation from the plate following full consolidation on the x-ray.

Variables and data sources/measurements

Demographic variables that were routinely collected included age, sex, type of work, symptom duration, treatment side, hand dominance, and the smoking status at the time of surgery. We reviewed the medical records to collect data on treatment of the initial injury, operative variables (such as the type and positioning of the fixation plate), and the occurrence of complications.

Patients completed the Dutch-language version of the patient rated wrist/hand evaluation (PRWHE) before surgery and at 3 and 12 months after surgery [22]. Previous research found that it is a very responsive patient-derived questionnaire to evaluate the treatment outcomes of UIS [23–25]. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in the PRWHE total score for patients who underwent USO for idiopathic UIS is 17 [26].

A hand therapist measured active range of motion (ROM) and grip strength before surgery and at 3 and 12 months after surgery. In this standardized examination following ICHOM guidelines [27], the ROM was measured in degrees from neutral using a goniometer. The goniometer was placed at the dorsal side of the wrist to measure wrist flexion/extension, radial/ulnar deviation, and pronation, and at the volar side of the wrist to measure supination. Wrist flexion, radial deviation, and pronation are reported as positive values; wrist extension, ulnar deviation, and supination as negative values. Grip strength was measured using an E-LINK Jamar-Style dynamometer (Biometrics, Newport, UK) following the methods of Mathiowetz et al. [28].

Complications were scored following the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement (ICHOM) Complications in Hand and Wrist conditions (ICHAW) classification, which is modified from the Clavien–Dindo classification for general surgery (see additional file 2: Table S2) [29]. This tool classifies complications within 12 months after surgery into different grades based on the treatment it requires. When a complication is not sufficiently relieved with minimally invasive treatment and more invasive treatment was given, only the complication with the highest grade is reported.

The primary outcome of this study was the change in PRWHE total score at 12 months after surgery. Secondary outcomes were complications, ROM, and grip strength.

Statistical analysis and study size

We performed a post hoc power analysis, with a conventional effect size of 0.3, α error probability of 0.05, and a sample size of 106 patients, and achieved a power of 92%.

We checked continuous data for normal distributions with histograms and quantile–quantile plots. Normally distributed data were displayed as mean values including standard deviations (SD) and skewed data were displayed as mean values including interquartile ranges (IQR). We used linear mixed models to compare data with more time points. We calculated the effect size of Cohen’s d between preoperative and 12 months PRWHE scores [30]. We compared continuous data between groups using independent T tests or Mann–Whitney U tests, and categorical data using chi-squared tests.

Because data were collected during daily clinical practice, missing data were expected in the PRWHE score at 12 months follow-up. We performed Little’s test to investigate whether the PRWHE scores at 12 months after surgery were missing completely at random [31]. Furthermore, we tested for significant differences in demographics and preoperative scores between patients who completed the PRWHE before and at 12 months after surgery (defined as responders) and patients who did not fill in the PRWHE at both time points (defined as nonresponders).

All computations were performed in R v4.0.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographics of the study population

Table 1 presents the demographics, surgical specifics, and preoperative measurements. The mean age of the study patients was 50 (standard deviation: ±11) years and 32% of the patients were males. In 42% of the patients, the UIS was secondary to distal radius fracture. Twelve patients had previously undergone a corrective osteotomy of the distal radius. Compared with the idiopathic UIS group, patients with UIS secondary to distal radius fracture were older (P = 0.044), had less range of motion in all directions except radial deviation (P < 0.001–0.012), had less grip strength (P = 0.008) at baseline, and had more millimeters resected during the USO (P < 0.001). Little’s test (P = 0.79) and the nonresponder analysis (additional file 3: Table S3) suggested that missing data on PRWHE at 12 months were missing completely at random.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | Overall | Idiopathic | Secondary to DRF | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 106 | 62 | 44 | |

| Age, mean (SD) (in years) | 50 (11) | 48 (11) | 52 (11) | 0.044 |

| Sex = Male, n (%) | 32 (30) | 19 (31) | 13 (30) | 1.000 |

| Duration of symptoms, median [IQR] | 12 [8, 30] | 18 [9, 36] | 12 [7, 24] | 0.089 |

| Type of work, n (%) | 0.605 | |||

| None | 32 (30) | 17 (27) | 15 (34) | |

| Light | 24 (23) | 14 (23) | 10 (23) | |

| Medium | 32 (30) | 18 (29) | 14 (32) | |

| Heavy | 18 (17) | 13 (21) | 5 (11) | |

| Dominant side affected = No, n (%) | 47 (44) | 25 (40) | 22 (50) | 0.430 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 0.421 | |||

| Yes | 22 (21) | 15 (24) | 7 (16) | |

| No | 81 (76) | 46 (74) | 35 (80) | |

| Unknown | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | |

| Preoperative PRWHE, mean (SD) | ||||

| Total score | 64 (18) | 66 (17) | 61 (20) | 0.195 |

| Pain score | 34 (9) | 34 (8) | 32 (10) | 0.240 |

| Function score | 61 (21) | 63 (20) | 58 (23) | 0.210 |

| Preoperative active ROMa, mean (SD) | ||||

| Wrist extension | −56 (14) | −60 (12) | −51 (15) | 0.001 |

| Wrist flexion | 52 (17) | 57 (16) | 46 (18) | 0.001 |

| Ulnar deviation | −23 (9) | −25 (9) | −21 (8) | 0.012 |

| Radial deviation | 18 (6) | 18 (6) | 16 (6) | 0.108 |

| Supination | −69 (17) | −72 (13) | −63 (20) | 0.006 |

| Pronation | 74 (13) | 77 (11) | 69 (15) | 0.003 |

| Preoperative grip strengthb, mean (SD) | 24 (11) | 27 (10) | 20 (11) | 0.008 |

| Ulna shorteningc (mm), median [IQR] | 4 [3, 4] | 3 [3, 4] | 4 [3, 4] | < 0.001 |

| Intervention = Concomitantd, n (%) | 18 (17) | 6 (10) | 12 (27) | 0.034 |

The P value is calculated between the groups based on etiology

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range, DRF distal radius fracture, PRWHE Patient Rated Wrist/Hand Questionnaire, ROM range of motion

a2% missing data

b13% missing data

c7% missing data

dCarpal tunnel release (n = 1); trigger finger release (n = 2); posterior interosseous nerve neurectomy (n = 2); pisiformectomy (n = 3); removal of hardware for distal radius fracture (n = 8); wafer (n = 1)

Patient-reported pain and function

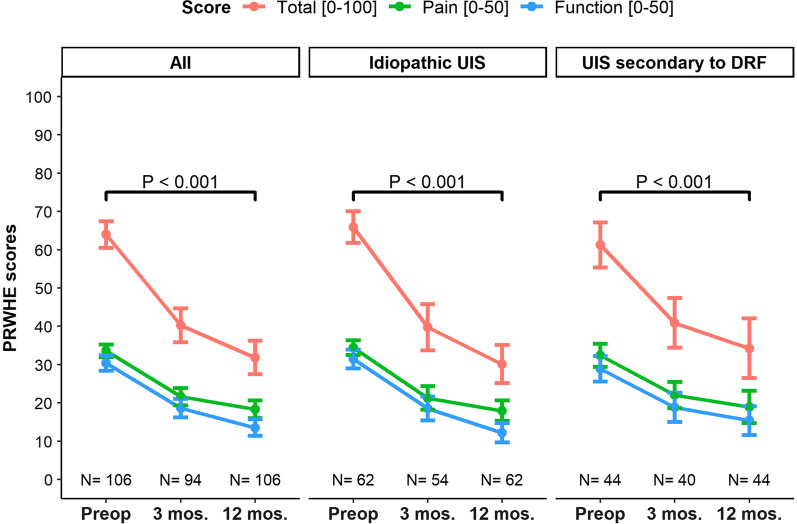

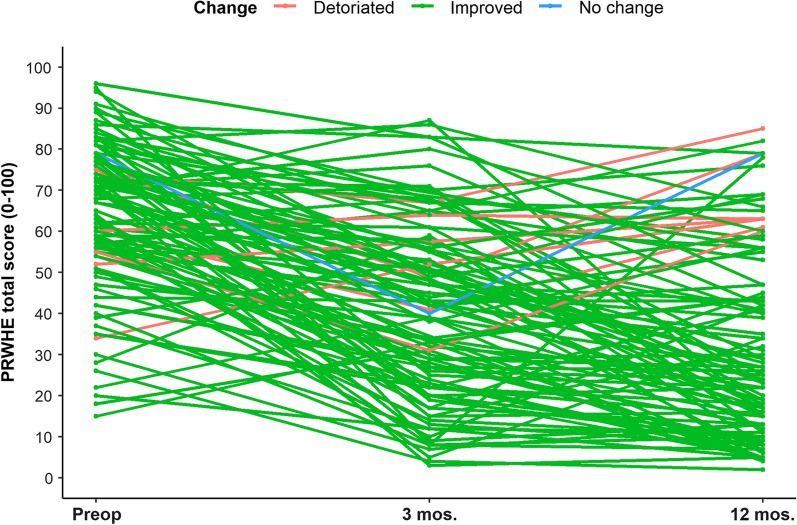

The PRWHE total score improved from a mean score of 64 (SD = 18) before surgery to 40 (22) at 3 months and 32 (23) at 12 months after surgery (P < 0.001; d = −1.4; Fig. 2). Although there was an overall improvement, a large variation in outcomes was observed at all time points (Fig. 3). The PRWHE pain score improved from 34 (9) to 18 (12) at 12 months (P < 0.001; d = −1.2), and the function score improved from 30 (10) to 14 (11) (P < 0.001; d = −1.4). There was no difference in the improvement in PRWHE total score (P = 0.99), pain score (0.894), or function score (P = 0.891) based on etiology.

Fig. 2.

The mean patient rated wrist/hand evaluation total score and subscores before ulna shortening osteotomy and at 3 and 12 months postoperatively. The error bars indicate standard errors. The P values indicate significance over time, i.e., whether differences between baseline and follow-up were significant

Fig. 3.

The patient rated wrist/hand evaluation total score before ulna shortening osteotomy and at 3 and 12 months postoperatively plotted for each patient

Active range of motion and grip strength

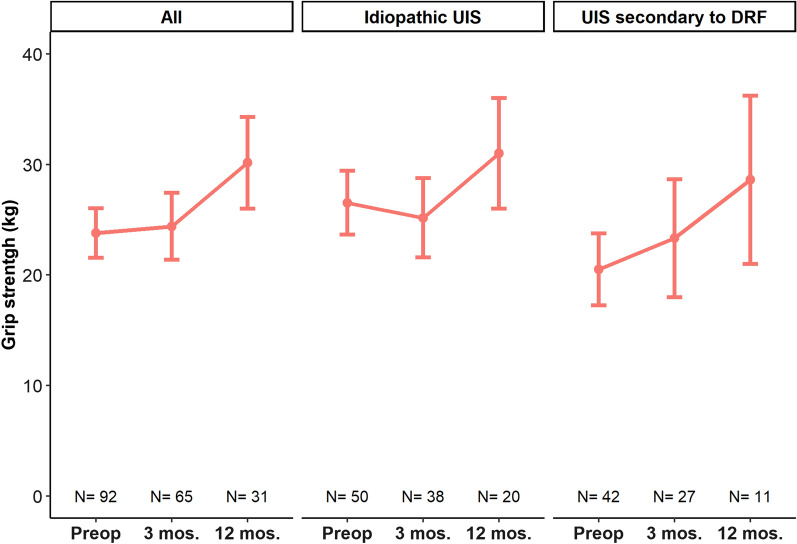

Table 2 presents the range of motion at all time points. Wrist extension improved in all patients, whereas wrist flexion, ulnar deviation, and radial deviation improved only in patients with secondary UIS. The overall mean grip strength improved from 24 (11) before surgery to 30 (12) at 12 months (P = 0.001), improvement was seen for both etiologies (P idiopathic = 0.006 and P secondary to DRF = 0.011) (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Range of motion before ulna shortening osteotomy and at 3 and 12 months postoperatively

| Group | Movement, mean (SD) | Preoperative | 3 months | 12 months | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Wrist extension | −56 (14) | −58 (12) | −64 (8) | < 0.001 |

| Wrist flexion | 52 (17) | 52 (12) | 60 (12) | 0.002 | |

| Ulnar deviation | −23 (9) | −23 (7) | −27 (8) | 0.017 | |

| Radial deviation | 18 (6) | 17 (7) | 20 (9) | 0.002 | |

| Pronation | −74 (13) | −71 (13) | −74 (11) | 0.656 | |

| Supination | 69 (17) | 65 (15) | 70 (13) | 0.835 | |

| Idiopathic | Wrist extension | −60 (12) | −59 (10) | −64 (8) | 0.022 |

| Wrist flexion | 57 (16) | 53 (12) | 60 (12) | 0.062 | |

| Ulnar deviation | −25 (9) | −24 (7) | −27 (7) | 0.175 | |

| Radial deviation | 18 (6) | 19 (8) | 21 (10) | 0.078 | |

| Pronation | −77 (11) | −74 (12) | −74 (9) | 0.218 | |

| Supination | 72 (13) | 67 (15) | 69 (13) | 0.260 | |

| Secondary to DRF | Wrist extension | −51 (15) | −57 (14) | −65 (10) | 0.002 |

| Wrist flexion | 46 (18) | 51 (13) | 59 (12) | 0.021 | |

| Ulnar deviation | −21 (8) | −22 (6) | −27 (9) | 0.035 | |

| Radial deviation | 16 (6) | 15 (6) | 20 (9) | 0.003 | |

| Pronation | −69 (15) | −68 (14) | −72 (15) | 0.682 | |

| Supination | 63 (20) | 63 (16) | 73 (13) | 0.151 |

There were 104 preoperative patients (idiopathic = 61; DRF = 43), 67 at 3 months (idiopathic = 37; DRF = 30), and 29 at 12 months (idiopathic = 19; DRF = 10)

DRF distal radius fracture

*P values indicate significance over time, i.e., whether differences between baseline and follow-up were significant

Fig. 4.

The mean grip strength (kg) before ulna shortening osteotomy and at 3 and 12 months postoperatively. The error bars indicate standard errors

Complications

Table 3 presents all complications. Sixty-four percent of all patients experienced at least one complication. Of the 80 complications, 50 (47%) were directly related to hardware irritation, 34 of which (32%) had their hardware removed. There were no refractures after plate removal. Six patients (6%) needed refixation because of nonunion; the characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 4. Five patients (5%) had subsequent therapy for persistent ulnar-sided wrist pain, two underwent hand therapy and/or splinting, one underwent TFCC reinsertion, one underwent pisiformectomy, and one underwent neurolysis.

Table 3.

Complications and reoperations within 12 months after ulna shortening osteotomy

| Complication | n |

|---|---|

| No complication | 38 (36% had no complications) |

| Grade I | 29 complications in 29 patients (27% had a Grade I complication) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 1 |

| Scar tenderness | 1 |

| Hardware irritation | 16 |

| Hand therapy | |

| ECU luxation | 1 |

| DRUJ instability | 1 |

| Midcarpal laxity | 1 |

| Radial tunnel syndrome | 1 |

| Persistent ulnar sided wrist pain | 1 |

| Splinting | |

| ECU tendinitis | 1 |

| Impaired pronation | 1 |

| Persistent ulnar-sided wrist pain | 2 |

| Delayed union needing bone stimulation | 2 |

| Grade II | Three complications in three patients (3% of the patients had a Grade II complication) |

| Corticosteroid injection | |

| Trigger finger | 3 |

| Grade IIIA | 0 complications (% had a Grade IIIA complication) |

| Grade IIIB | 48 complications in 39 patients (37% had a Grade IIIC complication) |

| Refixation after nonunion | 6 |

| Hardware removal | 34 |

| Persistent ulnar-sided wrist pain | |

| TFCC reinsertion | 1 |

| Pisiformectomy | 1 |

| Neurolysis | 1 |

| 3-LT tenodesis | 1 |

| Tenolysis | 4 |

| Grade IIIC | 0 complications |

TFCC triangular fibrocartilage complex

Table 4.

Patient and surgical characteristics of the patients that required bone stimulation and/or refixation for delayed union/nonunion

| Characteristic | Pt. 1 | Pt. 2 | Pt. 3 | Pt. 4 | Pt. 5 | Pt. 6 | Pt. 7 | Pt. 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46 | 71 | 35 | 48 | 63 | 53 | 41 | 46 |

| Sex | Female | Female | Male | Female | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| Duration of symptoms (months) | 5 | 12 | 10 | 60 | 5 | 24 | 18 | 9 |

| Type of work | Heavy | None | Heavy | Medium | None | Heavy | Medium | Medium |

| Side | Dominant | Nondominant | Dominant | Dominant | Dominant | Nondominant | Dominant | Dominant |

| Smoking status | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Etiology | DRF | DRF | DRF | Idiopathic | Idiopathic | Idiopathic | Idiopathic | Idiopathic |

| Plate | Acumed | AO | AO | Acumed | AO | Acumed | Acumed | Acumed |

| Shortening (mm) | 3, 5 | 4 | 4, 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | a |

| Traumatic injury after USO | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Bone stimulator (IGEA) used | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time to revisions surgery (days) | 126 | 119 | 233 (patient was too busy with work) | 143 | 173 | 221 | NAb | NAb |

| Experience level of surgeonc | III | IV | III | III | III | III | IV | III |

USO ulna shortening osteotomy, DRF distal radius fracture

aMissing

bNA not applicable; union achieved with bone stimulation and refixation not needed

cAccording to the classification by Tang and Giddins (I Non-specialist; II Specialist - less experienced; III Specialist - experienced; IV Specialist - highly experienced; V Expert)

Discussion

Ulnar impaction syndrome (UIS) is a condition at the ulnar side of the wrist that occurs because of chronic excessive loading across the ulnocarpal joint [1]. Ulna shortening osteotomy (USO) is a frequently used surgical treatment for patients with UIS [4, 5]. In this study, we report on the outcomes of USO using prospectively gathered and reliable patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in a relatively large sample size [6–9]. We found that patients with UIS reported less pain and improved function at 12 months after USO. However, there was a large variance in the outcome and a relatively high number of complications, ranging from minor to severe (which includes plate removal). Results of this study may be used in preoperative counseling and shared decision-making when considering USO.

Our study had several limitations. First, there were missing data in the patient and clinician-reported outcomes, making our findings not generalizable to the entire cohort. However, the data were missing at random and there were no baseline differences between responders and nonresponders. Thus, we are confident that the missing data did not influence our findings. A second limitation is that in several electronic patient dossiers, the indication for USO was not explicitly stated. Therefore, we had to categorize these patients retrospectively. Third, the study sample was not homogeneous regarding some factors that may influence the outcome of surgery. While all USOs were performed at the level of the diaphysis using an oblique cut, there was variation in the manner of the osteotomy (freehand versus specific USO devices) and the type and position of the fixation plate, which may have influenced the outcomes during follow-up. Although previous research did not find a difference in pain relief or return to work between freehand USO and specific USO devices [32, 33]. Fourth, some patients underwent concomitant surgery during the USO, which could have induced some co-treatment bias.

Previous studies have reported an overall improvement in patient-reported pain and function after USO in patients with UIS [6–9]. Our data are in line with previous studies and demonstrate improvement following USO in a relatively large sample size. USO can be considered an effective treatment for patients with UIS in general, but it should be noted that we observed a large variation in the patient-reported outcome at 12 months. Some patients remained impaired, and a large prevalence of complications occurred, ranging from minor to severe. The reason for the variation in the patient-reported outcome will be a focus of future research. We found mean improvement for various measures of range of motion over time. This improvement will probably not be clinically relevant as it is of the same magnitude as the measurement error of the goniometer [34]. However, the gain in patient-reported outcomes was not at the cost of the range of motion. This finding is in line with previous research [9, 35, 36]. The grip strength also improved over time.

The scoring of complications after USO following the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement Complications in Hand and Wrist conditions (ICHAW) is new. This system, with well-described definitions of complications, was designed to improve the standardization and transparency of complication registration after hand and wrist surgery. Six percent of the patients required refixation with bone graft for radiographically established nonunion. This finding is similar to the results of the meta-analysis reporting nonunion rates after oblique USO [37]. Little is known on the risk factors for nonunion after USO, as the complication is relatively infrequent and most studies on USO (including this one) lack power for statistical inference. Cha found that smoking, low bone density, and decreased range of motion were independently associated with nonunion after USO [38]. Interestingly, all our patients did not smoke at the time of the USO. Many other factors, such as the type of osteosynthesis material, experience of the surgeon, and comorbidities, may lead to an increased risk of nonunion. Our descriptive data may contribute to future meta-analyses on this topic.

Furthermore, 32% of the patients underwent subsequent surgery to remove the plate within 12 months after surgery. This number is expected to increase when applying longer follow-ups. Previous studies have also reported high rates of plate removal of, e.g., 19–43% [10, 39], and in other studies, the plate is routinely removed [40, 41]. Patients should therefore be informed that they might require subsequent surgery to remove the plate. Future research should identify which factors are associated with hardware removal.

In this study, we compared patients with UIS based on etiology. In line with de Runz et al., we found a larger ulna positive variance in patients with secondary UIS than in patients with primary UIS [42]. Despite these differences between the subgroups before surgery, we did not find differences in postoperative patient-reported pain and function. This was also previously reported by Nunez et al. [43]. Based on our findings, there is no need to inform patients differently based on the etiology of UIS regarding potential pain relief and gain of function after USO.

It should be noted that the patients in this study who underwent USO for UIS secondary to a distal radius malunion did not have considerable angulation in the distal radius. Patients with a clinically relevant radial head displacement undergo corrective osteotomy of the distal radius in our clinics. This in is line with other institutions who recommend a corrective osteotomy of the distal radius instead of USO in case of 10° palmar inclination or > 20° dorsal inclination from the normal tilt [9, 33, 44]. Stirling et al. investigated the patient-reported outcome following corrective osteotomy of the distal radius and also reported favorable results [45]. For patients with severe concomitant wrist instability, other treatment modalities may be necessary; however, this was outside the scope of this study.

This study involved a relatively large number of patients with UIS who underwent USO, evaluated using a standardized set of prospectively collected patient-reported and clinician-reported outcome measures. The routinely collected data provide valuable insights into the performance of the USO of our daily practice. Also, this study reflects the results from multiple surgeons performing diaphyseal oblique USO, which makes the outcomes more generalizable. We found beneficial outcomes in patients with primary UIS or secondary to distal radius malunion; however, patients should be informed that plate removal is often required and residual complaints might remain.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Postoperative therapeutic regime after ulna shortening osteotomy.

Additional file 2: Table S2. ICHOM Complications in Hand and Wrist conditions (ICHAW), modified and derived from Clavien-Dindo 2009.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Differences in demographic data and patient-reported outcomes between responders and non-responders.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients who participated and allowed their data to be anonymously used for the present study. Hand Wrist Study Group contributors: R. A. M. Blomme, B. J. R. Sluijter, D. J. J. C. van der Avoort, A. Kroeze, J. Smit, J. Debeij, E. T. Walbeehm, G. M. van Couwelaar, G. M. Vermeulen, J. P. de Schipper, J. F. M. Temming, J. H. van Uchelen, H. L. de Boer, K. P. de Haas, K. Harmsen, O. T. Zöphel, R. Feitz, G. J. Halbesma, J. S. Souer, R. Koch, S. E. R. Hovius, T. M. Moojen, X. Smit, R. van Huis, P. Y. Pennehouat, K. Schoneveld, Y. E. van Kooij, R. M. Wouters, J. J. Veltkamp, A. Fink, W. A. de Ridder, H. P. Slijper, R. W. Selles, J. T. Porsius, J. Tsehaie, R. Poelstra, M. C. Jansen, M. J. W. van der Oest, P. O. Sun, L. Hoogendam, J. S. Teunissen, Jak Dekker, M. Jansen-Landheer, M. ter Stege, J. M. Zuidam, J. W. Colaris, L. Duraku, E. P. A. van der Heijden, and D. E. van Groeninghen.

Abbreviations

- ECU

Extensor carpi ulnaris

- ICHAW

International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement Complications in Hand and Wrist conditions

- IQR

Interquartile range

- MCID

Minimal clinically important difference

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NSAID

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug

- PROM

Patient-reported outcome measure

- PRWHE

Patient rated wrist/hand evaluation

- ROM

Range of motion

- SD

Standard deviation

- STROBE

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- TFCC

Triangular fibrocartilage complex

- UIS

Ulnar impaction syndrome

- USO

Ulna shortening osteotomy

Authors’ contributions

J.S.T.: designed the study, reviewed electronic patient dossiers, performed the analysis, discussed the results, wrote and reviewed the manuscript. R.M.W.: designed the study, performed the analysis, discussed the results, wrote and reviewed the manuscript. S.A.S.: designed the study, reviewed electronic patient dossiers, discussed the results, and reviewed the manuscript. O.T.Z.: designed the study, treated the patients, reviewed electronic patient dossiers, discussed the results, and reviewed the manuscript. G.M.V.: designed the study, treated the patients, discussed the results, and reviewed the manuscript. S.E.R.H.: designed the study, treated the patients, discussed the results, and reviewed the manuscript. E.P.A.G.: designed the study, reviewed electronic patient dossiers, discussed the results, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study. The ethics committee of the Erasmus University Medical Centre Rotterdam approved the study protocol (NL/sl/MEC-2018-1088).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare no potential competing interests to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

J. S. Teunissen, Email: Joris.teunissen@radboudumc.nl

R. M. Wouters, Email: robbertwouters@gmail.com

S. Al Shaer, Email: san-alshaer@live.nl

O. T. Zöphel, Email: ozoephel@t-online.de

G. M. Vermeulen, Email: G.Vermeulen@xpertclinics.nl

S. E. R. Hovius, Email: Steven.Hovius@radboudumc.nl

E. P. A. Van der Heijden, Email: brigittevanderheijden@hotmail.com

The Hand-Wrist Study Group:

R. A. M. Blomme, B. J. R. Sluijter, D. J. J. C. van der Avoort, A. Kroeze, J. Smit, J. Debeij, E. T. Walbeehm, G. M. van Couwelaar, G. M. Vermeulen, J. P. de Schipper, J. F. M. Temming, J. H. van Uchelen, H. L. de Boer, K. P. de Haas, K Harmsen, O. T. Zöphel, R. Feitz, G. J. Halbesma, J. S. Souer, R. Koch, S. E. R. Hovius, T. M. Moojen, X. Smit, R. van Huis, P. Y. Pennehouat, K. Schoneveld, Y. E. van Kooij, R. M. Wouters, J. J. Veltkamp, A. Fink, W. A. de Ridder, H. P. Slijper, R. W. Selles, J. T. Porsius, J. Tsehaie, R. Poelstra, M. C. Jansen, M. J. W. van der Oest, P. O. Sun, L. Hoogendam, J. S. Teunissen, Jak Dekker, M. Jansen-Landheer, M. ter Stege, J. M. Zuidam, J. W. Colaris, L. Duraku, E. P. A. van der Heijden, and D. E. van Groeninghen

References

- 1.Sammer DM, Rizzo M. Ulnar impaction. Hand Clin. 2010;26:549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer AK, Werner FW. Biomechanics of the distal radioulnar joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984 doi: 10.1097/00003086-198407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sachar K. Ulnar-sided wrist pain: evaluation and treatment of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears, ulnocarpal impaction syndrome, and lunotriquetral ligament tears. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1489–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbaric K, Rujevcan G, Labas M, Delimar D, Bicanic G. Ulnar shortening osteotomy after distal radius fracture malunion: review of literature. Open Orthop J. 2015;9:98–106. doi: 10.2174/1874325001509010098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stockton DJ, Pelletier M-E, Pike JM. Operative treatment of ulnar impaction syndrome: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Eur. 2015;40:470–476. doi: 10.1177/1753193414541749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassan S, Shafafy R, Mohan A, Magnussen P. Solitary ulnar shortening osteotomy for malunion of distal radius fractures: experience of a centre in the UK and review of the literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101:203–207. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2018.0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isaacs J, Howard SB, Gulkin D. A prospective study on the initial results of a low profile ulna shortening osteotomy system. Hand. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11552-009-9226-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidle G, Kastenberger T, Arora R. Time-dependent recovery of outcome parameters in ulnar shortening for positive ulnar variance: a prospective case series. Hand. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1558944717702465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasan RC, Jain D, Richard MJ, Leversedge FJ, Mithani SK, Ruch DS. Isolated ulnar shortening osteotomy for the treatment of extra-articular distal radius malunion. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:1106–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan SKL, Singh T, Pinder R, Tan S, Craigen MA. Ulnar shortening osteotomy: are complications under reported? J Hand Microsurg. 2015;7:276–282. doi: 10.1007/s12593-015-0201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Constantine KJ, Tomaino MM, Herndon JH, Sotereanos DG. Comparison of ulnar shortening osteotomy and the wafer resection procedure as treatment for ulnar impaction syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2000 doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.jhsu025a0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darlis NA, Ferraz IC, Kaufmann RW, Sotereanos DG. Step-cut distal ulnar-shortening osteotomy. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30:943–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anon. GemsTracker; Erasmus MC, Equipe Zorgbedrijven. https://gemstracker.org. Accessed 3 Aug 2020

- 14.Selles RW, Wouters RM, Poelstra R, van der Oest MJW, Porsius JT, Hovius SER, Moojen TM, van Kooij Y, Pennehouat P-Y, van Huis R, Vermeulen GM, Feitz R, Slijper HP. Routine health outcome measurement: Development, design, and implementation of the Hand and Wrist Cohort. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer AK. Triangular fibrocartilage complex lesions: a classification. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14:594–606. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(89)90174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imaeda T, Nakamura R, Shionoya K, Makino N. Ulnar impaction syndrome: MR imaging findings. Radiology. 1996;201:495–500. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.2.8888248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerezal L, del Piñal F, Abascal F, García-Valtuille R, Pereda T, Canga A. Imaging findings in ulnar-sided wrist impaction syndromes. Radiogr A Rev Publ Radiol Soc North Am Inc. 2002;22:105–121. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.1.g02ja01105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang JB, Giddins G. Why and how to report surgeons’ levels of expertise. J Hand Surg Eur. 2016;41:365–366. doi: 10.1177/1753193416641590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vos D, Hanson B, Verhofstad M. Implant removal of osteosynthesis: the Dutch practice. Results of a survey. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2012;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1752-2897-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vos DI, Verhofstad MHJ. Indications for implant removal after fracture healing: a review of the literature. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg Off Publ Eur Trauma Soc. 2013;39:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s00068-013-0283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Videler AJ, De ST. Nederlandse versie van de patient rated wrist/hand evaluation. Ned Tijdschr Handtherapie. 2008;17(2):8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacDermid JC. The PRWE/PRWHE update. J hand Ther Off J Am Soc Hand Ther. 2019;32:292–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacDermid JC, Turgeon T, Richards RS, Beadle M, Roth JH. Patient rating of wrist pain and disability: a reliable and valid measurement tool. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:577–586. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omokawa S, Imaeda T, Sawaizumi T, Momose T, Gotani H, Abe Y, Moritomo H, Kanaya F. Responsiveness of the Japanese version of the patient-rated wrist evaluation (PRWE-J) and physical impairment measurements in evaluating recovery after treatment of ulnocarpal abutment syndrome. J Orthop Sci Off J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 2012;17:551–555. doi: 10.1007/s00776-012-0265-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JK, Park ES. Comparative responsiveness and minimal clinically important differences for idiopathic ulnar impaction syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1406–1411. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2843-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anon. ICHOM. Hand and Wrist Conditions Data Collection Reference Guide Version 1.0.0. 2020. https://connect.ichom.org/standard-sets/hand-and-wrist-conditions/. Accessed 1 Apr 2021

- 28.Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Volland G, Kashman N. Reliability and validity of grip and pinch strength evaluations. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9:222–226. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(84)80146-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–196. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen J. Statistical power for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:1198–1202. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teunissen JS, Feitz R, Al Shaer S, Hovius S, Selles RW, Hand-Wrist Study Group. Van der Heijden B. Return to usual work following an ulnar shortening osteotomy: a sample of 111 patients. J Hand Surg Am. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2021.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tatebe M, Shinohara T, Okui N, Yamamoto M, Imaeda T, Hirata H. Results of ulnar shortening osteotomy for ulnocarpal abutment after malunited distal radius fracture. Acta Orthop Belg. 2012;78:714–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Kooij YE, Fink A, van der Sanden MWN, Speksnijder CM. The reliability and measurement error of protractor-based goniometry of the fingers: a systematic review. J hand Ther Off J Am Soc Hand Ther. 2017;30:457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen NC, Wolfe SW. Ulna shortening osteotomy using a compression device. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28:88–93. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2003.50003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finnigan T, Makaram N, Baumann A, Ramesh K, Mohil R, Srinivasan M. Outcomes of ulnar shortening for ulnar impaction syndrome using the 2.7 mm AO ulna shortening osteotomy system. J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol. 2018;23:82–89. doi: 10.1142/S242483551850011X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owens J, Compton J, Day M, Glass N, Lawler E. Nonunion rates among ulnar-shortening osteotomy for ulnar impaction syndrome: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2019;44:612.e1–612.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cha SM, Shin HD, Ahn KJ. Prognostic factors affecting union after ulnar shortening osteotomy in ulnar impaction syndrome: a retrospective case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:638–647. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verhiel SHWL, Özkan S, Eberlin KR, Chen NC. Nonunion and reoperation after ulna shortening osteotomy. Hand. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1558944719828004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cha S-M, Shin H-D, Kim K-C. Positive or negative ulnar variance after ulnar shortening for ulnar impaction syndrome: a retrospective study. Clin Orthop Surg. 2012;4:216–220. doi: 10.4055/cios.2012.4.3.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iwatsuki K, Tatebe M, Yamamoto M, Shinohara T, Nakamura R, Hirata H. Ulnar impaction syndrome: incidence of lunotriquetral ligament degeneration and outcome of ulnar-shortening osteotomy. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:1108–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Runz A, Pauchard N, Sorin T, Dap F, Dautel G. Ulna-shortening osteotomy: outcome and repercussion of the distal radioulnar joint osteoarthritis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:175–184. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nuñez FAJ, Marquez-Lara A, Newman EA, Li Z, Nuñez FAS. Determinants of pain and predictors of pain relief after ulnar shortening osteotomy for ulnar impaction syndrome. J Wrist Surg. 2019;8:395–402. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1692481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Löw S, Mühldorfer-Fodor M, Pillukat T, Prommersberger K-J, van Schoonhoven J. Ulnar shortening osteotomy for malunited distal radius fractures: results of a 7-year follow-up with special regard to the grade of radial displacement and post-operative ulnar variance. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:131–137. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1892-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stirling PHC, Oliver WM, Ling Tan H, Brown IDM, Oliver CW, McQueen MM, Molyneux SG, Duckworth AD. Patient-reported outcomes after corrective osteotomy for a symptomatic malunion of the distal radius. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B:1542–1548. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B11.BJJ-2020-0848.R3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Postoperative therapeutic regime after ulna shortening osteotomy.

Additional file 2: Table S2. ICHOM Complications in Hand and Wrist conditions (ICHAW), modified and derived from Clavien-Dindo 2009.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Differences in demographic data and patient-reported outcomes between responders and non-responders.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.