Abstract

Neonatal sepsis is a prime cause of neonatal deaths across the globe. Presently, various medical tests and biodevices are available in neonatal care. These diagnosis platforms possess several limitations such as being highly expensive, time-consuming, or requiring skilled professionals for operation. These limitations can be overcome through biosensor development. This work discusses the assembling of an electrochemical sensing platform that is designed to detect the level of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). The sensing platform was moderated with nanomaterials molybdenum disulfide nanosheets (MoS2NSs) and silicon dioxide-modified iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4@SiO2NPs). The integration of nanomaterials helps in accomplishing the improved characteristics of the biosensor in terms of conductivity, selectivity, and sensitivity. Further, the molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) approach was incorporated for sensing the presence of TNF-α on the surface of the working electrode. The electrochemical response of the electrode was recorded at different conditions. A broad concentration range was selected to optimize the biosensor from 0.01 pM to 100 nM. The sensitivity of the biosensor was higher and it exhibits a lower detection limit (0.01 pM).

Keywords: Electrochemical biosensor, Molecularly imprinted polymer, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), Neonatal sepsis

Introduction

Neonatal sepsis is a systemic condition occurring in the presence of fungi, viruses, or bacteria in the bloodstream of neonates and resulting in significant morbidity and mortality (Shane et al. 2017). Based on the age of onset, it can be represented into two types such as early-onset sepsis (EOS) and late-onset sepsis (LOS). Detection of neonatal sepsis is challenging due to uncertain symptoms as they are similar to normal infection (Chauhan et al. 2017b; Balayan et al. 2020). The traditional method incorporated for neonatal sepsis detection is the isolation of the pathogens from the body fluids, but this method has limitations such as producing results after a long time, requiring experts for operating, and is expensive. The delay in the detection of sepsis leads to organ dysfunction and causes death (Wynn et al. 2014). Recently, the development of biosensors is emerging in the biomedical field. These biosensors can facilitate in overcoming the constraints of the traditional methods as they produce rapid results; they are highly sensitive and specific, possess low cost for development, and no professionally trained user is needed for the operation. These biosensors can be developed into home-based devices or point-of-care devices. Hence, this work is a representation of a sensing platform that is assembled for determining tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a biomarker for neonatal sepsis on the surface of a screen-printed electrode (SPE). Several reported biosensors are based on multiple principles for TNF-α level identification as described in Table 1; however, they are less sensitive, time-consuming, and require a large sample volume. On the other side, this developed biosensor is highly sensitive, and a very little sample volume is required for experimentation and the platform produces rapid results.

Table 1.

Comparing parameters for developed and reported biosensors

| S. No | Biosensor | Platform/electrode substrate | Limit of detection | Detection range | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Electrochemical | Ab-HRP/TNF-α/1-HT/TNF-α-Apt/AuNPs/CoHCF/SPE | 0.52 pg mL−1 | 1–100 pg mL−1 | Ghalehno et al. (2019) |

| 2 | Piezoeletric | Quartz crystal microbalance | 1.62 pg mL−1 | 0–4 ng mL−1 | Pohanka (2018) |

| 3 | Optical | Anti-TNF-mAb | 0.13 μg mL−1 | 100–1500 ng mL−1 | Rajeev et al. (2018) |

| 4 | Electrochemical | Anti-TNF-α/CMA/Au electrode | 3.1 pg mL−1 | 1–100 pg mL−1 | Bellagambi et al. (2017) |

| 5 | Electrochemical | ISFET | 1 pg mL−1 | 1–50 pg mL−1 | Halima et al. (2021) |

| 6 | Electrochemical | MIP/Fe3O4@SiO2NPs/MoS2NSs/SPE | 0.01 pM | 0.01 pM–100 nM | This work |

Ab antibody, HRP horseradish peroxidase, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor-alpha, 1-HT 1-hexanthiol, TNF-α-Apt tumor necrosis factor-alpha aptamer, AuNPs gold nanoparticles, CoHCF cobalt hexacyanoferrate, SPE screen-printed electrode, CMA 4-carboxymethylaniline, Au gold, mAb monoclonal antibody, ISFET ion-sensitive field-effect transistor, MIP molecularly imprinted polymer, Fe3O4@SiO2NPs silicon dioxide-modified iron oxide nanoparticles, MoS2NSs molybdenum disulfide nanosheets

TNF-α are proinflammatory chemokines/cytokines that are synthesized during infection in the body. It takes about 2–4 h for the elevation of TNF-α level in the body after introduction to inflammation. The properties of TNF-α are similar to that of interleukin-6. It has been reported that the level of TNF-α is higher in newborns that are infected with septic conditions when compared with healthy neonates (Sharma et al. 2018). A meta-analysis was carried out with 23 trials describing the moderate accuracy for the detection of both EOS (sensitivity = 66%, specificity = 76%) and LOS (sensitivity = 68%, specificity = 89%) in neonates (Lv et al. 2014).

Recently, nanomaterials play a vital role in the development of sensing technology due to their sizes in nanoscale properties. The nanosize of particles provides enhanced conductivity, sensitivity, and specificity of the system. Toxicity in the biological system can occur due to the specific parameter of the nanomaterials such as surface volume, size, lateral dimension, purification, and total numbers of layers. These parameters significantly affect the interaction between the nanostructure and the biological system. This can lead to the same component exhibiting different properties (for antibacterial and cytotoxic mechanisms) based on the varying physiochemical parameters (Domi et al. 2020; Fojtů et al. 2017). The toxic effect of the nanomaterials can be reduced after evaluating these parameters carefully.

The fabricated electrochemical biosensor was altered with molybdenum disulfide nanosheets (MoS2NSs) and silicon dioxide-modified iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4@SiO2NPs). Recently, due to exceptional chemical and physical properties, two-dimensional materials are emerging as advanced technology materials. They are incorporated in device development, because these materials provide a higher ratio of surface area and volume, and also they are highly sensitive to the analyte. As they have various unique properties (flexibility, conductivity, mechanical, and thermal strength), they are widely used in the development of miniaturized devices (Butler et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2020; Wen et al. 2018). Further, the MoS2NSs result in the generation of more active sites and provide higher charge transfer (Zhao et al. 2018; Rawat et al. 2020). Moreover, the electrode was modified with Fe3O4@SiO2NPs to enhance the conductivity of the working electrode. The iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4NPs) are beneficial to provide a microenvironment that facilitates the direct exchange of electrons with an electrode (Chauhan and Pundir, 2012; Chauhan et al. 2016, 2017a). Due to several exceptional properties of silicon dioxide (SiO2) like good biocompatibility, low toxicity makes them an important composite material in the biomedical field. It has a stable nature and very simple steps are required for the preparation (Korzeniowska et al. 2013; Lahcen et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2015; Sun et al. 2017).

Afterward, the electrode was modified with molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) prepared for TNF-α. The MIP was electrodeposited on the surface of Fe3O4@SiO2NPs/MoS2NSs/SPE. The MIP is highly selective for the targeting biomolecule, they have high stability and require low cost for development (Yang et al. 2019). These properties allow integration of MIP for the development of electrochemical biosensors and they are also incorporated in various areas such as environmental, life sciences, and pharmaceutical (Wang et al. 2018; Li et al. 2018; Lopes et al. 2017). The electrochemical biosensor was evaluated for the determination of TNF-α (a biomarker) concentration in the case of neonatal sepsis. The developed biosensor can be employed for a dynamic concentration range and indicate a lower detection limit (LOD). The biosensor is promised to show higher sensitivity and selectivity.

Experimental

Chemicals and equipment

TNF-α was obtained from a US-based company MyBioSource. Acetonitrile, methyl methacrylate, and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Ferrous and Ferric chloride anhydrous, azobisisobutyronitrile, hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hydroxide, potassium ferro and ferricyanide, sulfur, ammonium molybdate, hydrazine, ethanol, methanol, ammonia, and (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane were procured from Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt Ltd. (SRL), India. The SPE used for the sensor development was acquired from PalmSens Compact Electrochemical Interfaces, The Netherlands. To avoid impurities, all the apparatus were cleaned with the autoclave process before starting the experiments. The chemicals were used in their pure form and all the solutions were prepared in distilled water (DW).

Development of molybdenum disulfide nanosheets

The preparation of MoS2NSs was carried out with a hydrothermal process. A mixture was prepared in 20 mL DW mixed with sulfur (0.435 gm) and ammonium molybdate (1.2 gm) in the presence of hydrazine (N2H4.H2) a reducing agent (12 M, 85%) with continuous stirring (30 min). Then the mixture was autoclaved for 40 h at 180 C and kept for cooling at atmospheric temperature. The obtained product was washed and centrifuged using DW, HCl, and ethanol three times to remove unreacted reagents. Finally, the product was kept for drying for 30 h (60 ºC) in a vacuum chamber (Ye et al. 2014; Singh et al, 2021).

Preparation of iron oxide nanoparticles

The synthesis of Fe3O4NPs was accomplished by performing the reported co-precipitation method (Kang et al. 1996). An aqueous solution with 25 mL of DW and 0.85 mL of HCl (37%) containing 2.0 gm of ferrous chloride (0.015 M) and 5.2 gm of ferric chloride (0.03 M) (Fe(II):Fe(III) = 0.5) was prepared. The prepared mixture of iron salts under vigorous continuous stirring was dropwise added in a solution of sodium hydroxide (250 mL, 1.5 M) at normal temperature. Further, the mixture was stirred for 30 min for nucleation reaction when the cationic and alkaline solutions were completely added. The reaction was initiated with nitrogen purging and maintaining the pH of the solution as 11 and 12. A black precipitate was formed that was obtained with centrifugation at 4000 rpm for continuous processing of 15 min. Further, the product was washed using DW to remove unreacted reagents and salts. The synthesized Fe3O4NPs were neutralized using 500 mL HCl (0.01 M) with continuous stirring. The Fe3O4NPs were separated at 4000 rpm centrifugation for 15 min and dispersed in DW for further experiments (10 mg/mL) (Sanaeifar et al. 2017).

Preparation of silicon dioxide-modified iron oxide nanoparticles

The Fe3O4NPs were modified with silicon dioxide following the modified Stober hydrolysis method. A mixture was prepared in ethanol/DW (w1/w2 = 1:1) with 300 mg Fe3O4NPs and stirring it for 15 min. Then a solution of ammonia (5 mL) and (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (2 mL) was prepared and added into the mixture for 12 h at 50 °C. The formed product Fe3O4@SiO2 was separated using magnetic beads and further washing the particles with DW and drying them under vacuum conditions (Sun et al. 2017).

Synthesis of MIP for TNF-α

The synthesis of the imprinted polymer was obtained with bulk polymerization using methyl methacrylate, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, and TNF-α. A mixture was prepared with methyl methacrylate, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, and template in 50 mL of acetonitrile and the sonication of this mixture was done for 45 min. After that, the mixture was carried out with nitrogen purging for 10 min and adding 250 mg of azobisisobutyronitrile. Then the tube was sealed maintaining inert conditions and kept in a water bath for 2 days at temperature 45 °C to carry out the polymerization process. The MIPtemplate obtained after polymerization was dried and crushed into fine powder for surface characterizations. A mixture of methanol and acetic acid was prepared for washing the white polymer to remove the TNF-α molecule and then the sample was kept for drying (Yücebaş et al. 2020; Jain et al. 2020).

For control experiments, non-imprinted polymer (NIP) was synthesized following similar steps. But during NIP synthesis, no biomolecule (template) was used in the process.

Characterization and electrochemical studies for the developed biosensor

The microspheres synthesized were optimized using Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) to determine the pore diameter and isotherm of the synthesized material. Further, the electrode was characterized at each modification stage with electrochemical measurements on the potentiostat (Model: SP-150, Biologics) in an electrochemical cell consisting of three electrodes, reference, auxiliary, and working, dipped in a mediator solution for the completion of an electric circuit.

Designing of TNF-α imprinted electrochemical biosensor on SPE

For fabricating the working electrode, the surface of the SPE was coated with MoS2NSs. A dispersion was prepared in 10 mL of DW using 100 mg of MoS2NSs powder obtained after synthesis. The sonication was carried out for 1 h for proper dispersion. From this prepared solution, 50 μL was used for electrodeposition on the surface of SPE. For electrodeposition, cyclic voltammetry (CV) was incorporated while applying potential ranging from 0.0 to − 1.0 V for 10 CV cycles in the presence of an electron mediator solution of molarity 5 mM (Singh et al. 2021; Jain et al. 2019).

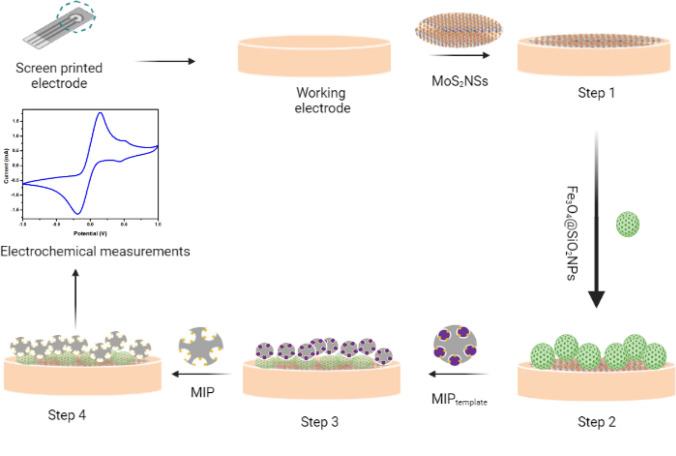

Furthermore, the surface of the working electrode on SPE was coated with Fe3O4@SiO2NPs using CV when applying a voltage from − 1.0 to + 1.0 V at a scan rate of 50 mV/s for ten cycles. A mixture of 100 mg/mL of Fe3O4@SiO2NPs and DW was prepared for electrodeposition on the MoS2NSs-modified electrode. Afterward, synthesized MIP microspheres were coated on Fe3O4@SiO2NPs/MoS2NSs/SPE with CV for 15 cycles applying potential from − 0.2 V to + 0.6 V. The SPE was then washed once with DW and dried at atmospheric temperature. This modified electrode was now used for other optimizations. Scheme 1 shows a pictorial representation of steps involved in assembling the sensing platform.

Scheme 1:

Pictorial illustration for stepwise development of an electrochemical biosensor for tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Step 1: Electrodeposition of molybdenum disulfide nanosheets (MoS2NSs). Step 2: Deposition of silicon dioxide-modified iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4@SiO2NPs). Step 3: Electrocoating of molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP). Step 4: Template removal from polymer and measurement of electrochemical response

Results

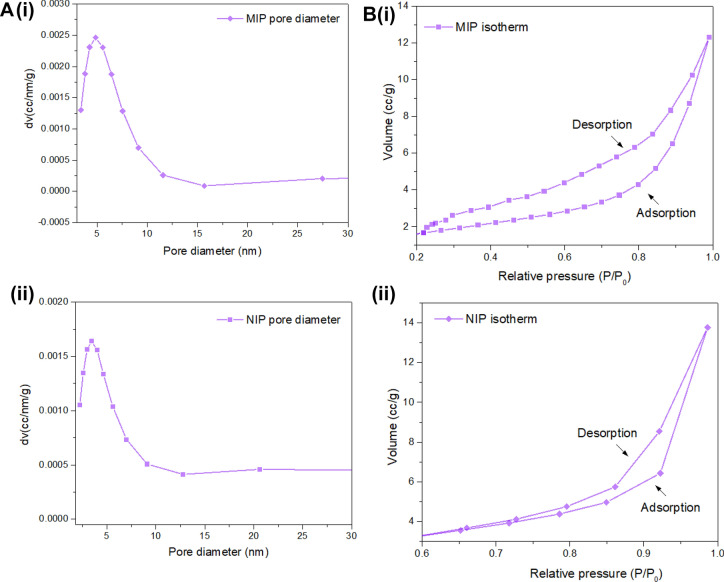

Nitrogen adsorption analysis of synthesized MIP microspheres for TNF-α

The nitrogen adsorption was incorporated in the presented study to determine the pore size, surface area, and pore volume of synthesized MIP microspheres. The results observed for both MIP and NIP are depicted in Table 2. A large surface area and pore diameter were obtained in the case of MIP due to the presence of imprinting structures of TNF-α on polymer, and large binding sites were obtained with formed cavities on the surface of MIP. The pore sizes of both the samples were obtained in a range from 2 to 50 nm; therefore, these polymers can be described as mesoporous structures (Qi et al. 2017). Figure 1A (i) and (ii) illustrates the graph obtained for the pore diameter of MIP and NIP, respectively. Figure 1B (i) and (ii) describes the isotherm graph for MIP and NIP, respectively; the graph shows the hysteresis loop following H-type. A narrow gap was calculated for the MIP and NIP loop; hence, the graph follows type-1 isotherm characteristics (Adu et al. 2020).

Table 2.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis for molecular imprinted polymer (MIP) and non-imprinted polymer (NIP)

| Polymer | BET surface area (m2/g) | Pore volume (cm3/g) | Pore diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIP | 9.991 | 0.023 | 3.810 |

| NIP | 9.218 | 0.021 | 2.225 |

Fig. 1.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis for molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) and non-imprinted polymer (NIP). A Pore size distribution: (i) MIP; (ii) NIP. B Adsorption and desorption graph: (i) MIP; (ii) NIP

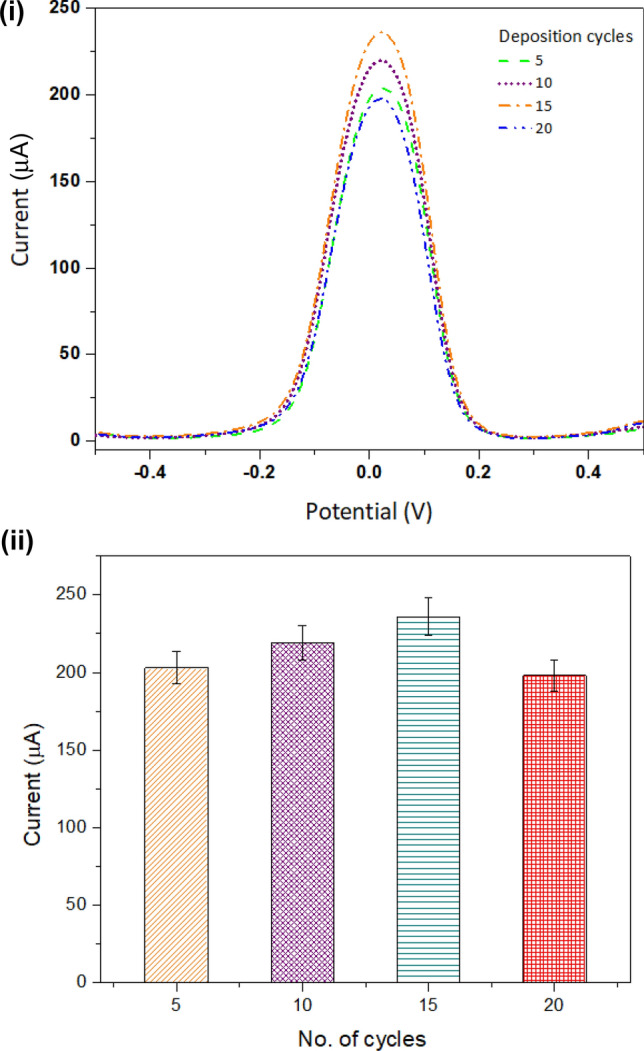

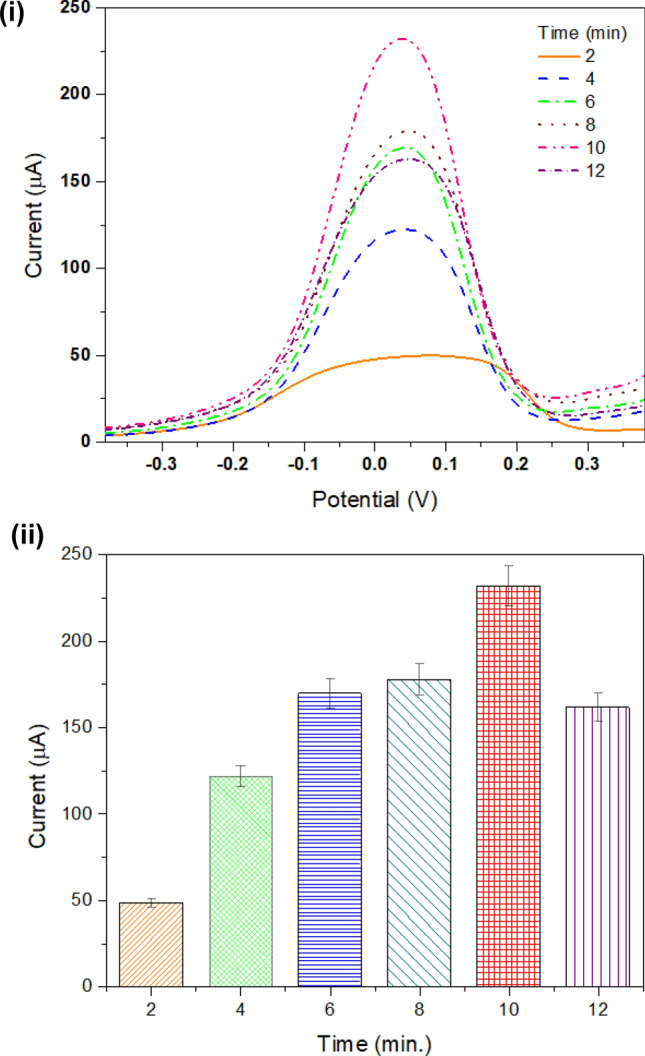

Optimizing deposition of MIP on the working electrode

The synthesized MIP was deposited on the electrode surface using the CV with different deposition cycles (5, 10, 15, and 20). Thereafter, the electrode was evaluated with differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) to measure the current response of the electrode with varying cycles as shown in Fig. 2 (i). A bar graph was plotted with peak currents as shown in Fig. 2 (ii). The obtained results show that a higher peak current (236 μA) was generated in the case when the MIP was deposited with 15 CV cycles. Beyond 15 cycles, the current decreases due to the generation of higher resistance because of the presence of polymer on the surface of the working electrode, hence resisting charge flow in the system. Therefore, 15 cycles were obtained as the optimized cycles for MIP deposition on the working electrode surface.

Fig. 2.

Deposition cycle: deposition of molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) on electrode surface with different cycles. (i) Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) measurement for varying cycles for MIP deposition. (ii) Bar graph demonstrates peak current obtained in DPV measurements for varying cycles (5, 10, 15, and 20)

Evaluating working electrode for different elution times to remove TNF-α molecule

A study was performed to determine the elution time for the TNF-α molecule from MIPtemplate (without washed MIP; when the template was present) deposited on the surface of the modified SPE. A DPV measurement was done to obtain the current response of the electrode with varying elution time from 2 to 12 min. with an interval of two units. The highest current was obtained after 10 min; beyond this, it was observed that the current peak decreases. Hence, for further experiments, the elution time of 10 min was selected. The DPV measurements of elution time are shown in Fig. 3 (i). Peak analysis of the DPV measurements is represented in the form of a bar graph in Fig. 3 (ii).

Fig. 3.

Elution time: evaluating elution of MIP on electrode surface: (i) DPV measurement curve; (ii) representation of peak current at different elution times 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12

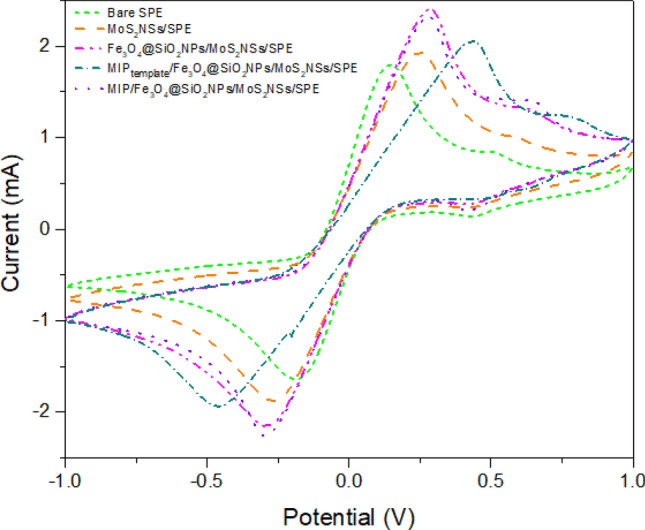

Studying electrode modification with cyclic voltammetry

The behavior of the analyte is generally revealed by using CV. Therefore, to study the modification of the working electrode, it was evaluated with CV measurements. Figure 4 illustrates the response of the electrode when examined with CV in a ferro/ferri mediator solution (5 mM). The working electrode was evaluated when voltage was applied from − 1.0 to + 1.0 V at a scan rate of 80 mV/s. The CV response was recorded for a bare electrode in the presence of an electron mediator which shows very low anodic (+ 1.81 mA) and cathodic (− 1.63 mA) peaks. After the electrode was improved with MoS2NSs, the obtained anodic and cathodic peaks increase to + 1.92 mA and − 1.88 mA, respectively. This current enhancement was observed because the presence of MoS2NSs generates large active sites resulting in higher electron transfer (Singh et al. 2021). A further modification was carried out with Fe3O4@SiO2NPs on the modified SPE surface indicating higher anodic (+ 2.42 mA) and cathodic peaks (− 2.17 mA). This enhancement can be due to the large surface area that is obtained while coating Fe3O4@SiO2NPs on the working electrode. Further, the electrode was modified using MIPtemplate microspheres synthesized for TNF-α. After MIPtemplate modification on an electrode surface, the current value decreased to + 2.06 mA for anodic peak and − 1.94 mA for cathodic peak. Higher resistance is created on the electrode surface that blocks current flow and decreases peak current in the system. The template was then removed out from the working electrode surface. The electrode response was obtained in electron mediator solution. The anodic and cathodic peaks increase to + 2.33 mA and − 2.24 mA, respectively. This enhancement was obtained due to the removal of the molecule. Besides, higher binding efficiency and specificity were obtained.

Fig. 4.

Modification of electrode: cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements for electrode modification at every step: bare screen-printed electrode (SPE); MoS2NSs/SPE; Fe3O4@SiO2NPs/MoS2NSs/SPE; MIPtemplate/Fe3O4@SiO2NPs /MoS2NSs/SPE; MIP/Fe3O4@SiO2NPs/MoS2NSs/SPE

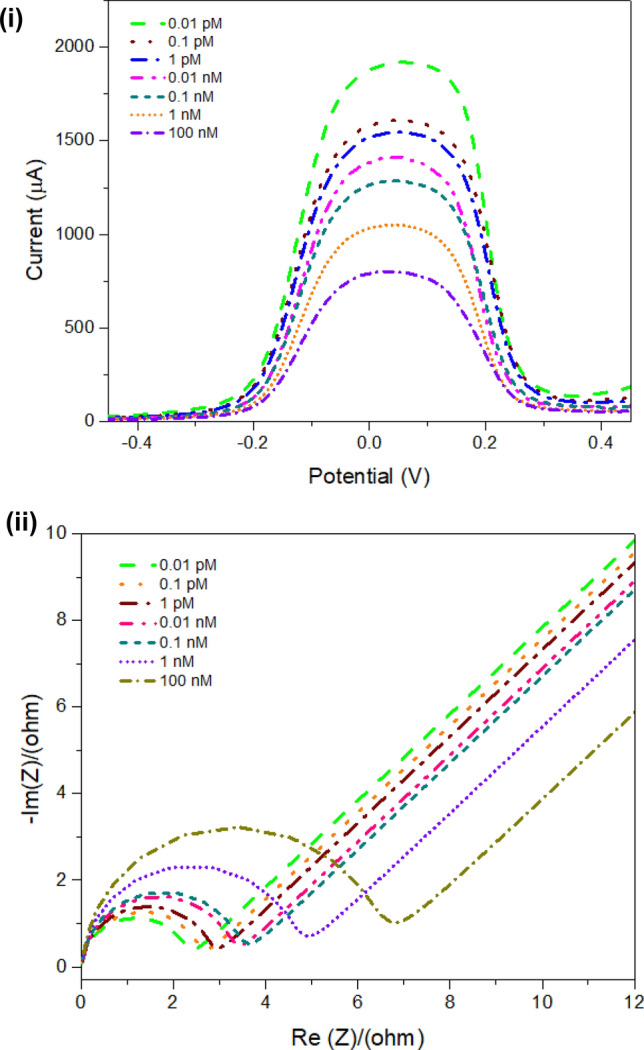

Optimization of TNF-α concentrations on the developed sensor

The effect of TNF-α concentrations were studied on the surface of the modified working SPE using the square wave voltammetry (SWV). The biosensor response was studied by different TNF-α concentrations within a range of 0.01 pM–100 nM. A linear response was observed for biosensor activity and TNF-α concentration. Figure 5 (i) shows SWV measurements for varying concentrations of TNF-α. The graph pattern was obtained showing that with increasing concentrations, the peak current value decreases, because at higher concentrations of TNF-α the molecules block the active bindings sites and create resistance on the electrode surface, leading to lower current generation. This study was further confirmed with the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy as shown in Fig. 5 (ii). The Nyquist plot shows a decrease in the resistance charge transfer value with decreasing concentrations, justifying lower resistance generated at lower concentrations of TNF-α. This study defines that the developed approach can be adopted for the identification of TNF-α at lower concentrations in samples due to higher specificity and sensitivity.

Fig. 5.

Different concentration studies: (i) square wave voltammetry (SWV) measurements for varying concentrations on screen-printed electrode in a range from 0.01 pM to 100 nM; (ii) Nyquist plot for varying concentrations (0.01 pM, 0.1 pM; 1 pM, 0.01 nM, 0.1 nM, 1 nM, and 100 nM)

Evaluation of the developed biosensor

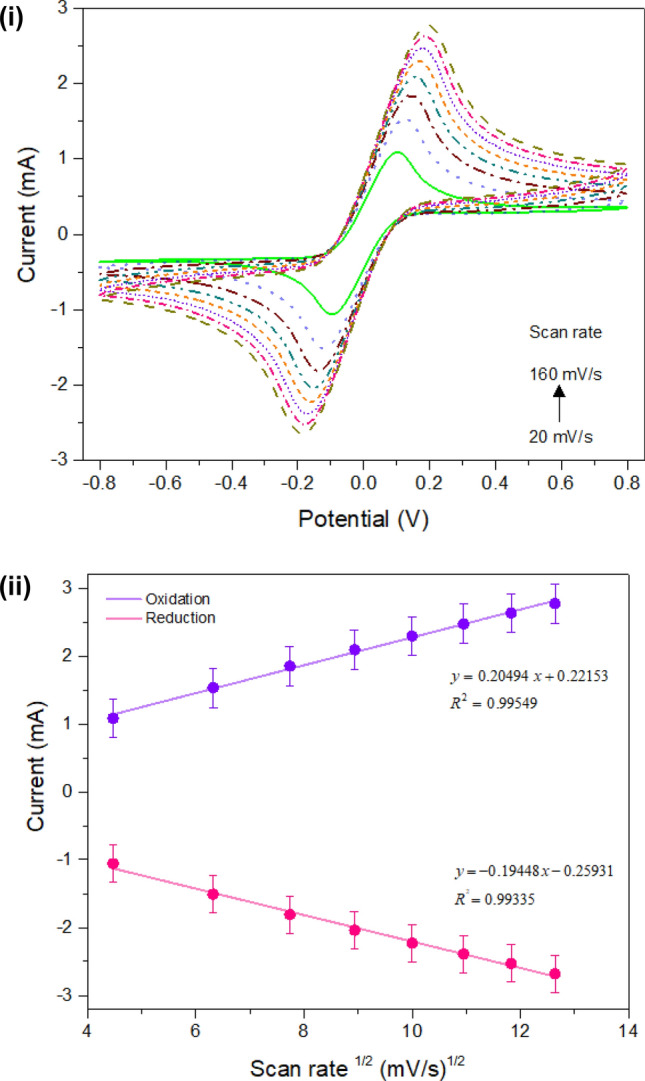

Scan rate studies for the modified biosensor

A scan rate study was performed for the system to check its stability. This experiment helps in studying the reaction mechanism (oxidation/reduction) of the analyte on an electrode surface that occurred due to the adsorption or diffusion process mechanism. The CV response was recorded with an increasing scan rate linearly from 20 to 160 mV/s as shown in Fig. 6 (i). The voltammogram shows that the increasing scan rate leads to increased oxidation and reduction peaks. A linear relationship for scan rate (square root) vs peak current for oxidation and reduction is given in Fig. 6 (ii).

Fig. 6.

Scan rate studies: (i) CV measurements for different scan rates from 20 to 160 mV/s; (ii) calibration curve for oxidation and reduction peak versus square root (√) of scan rate

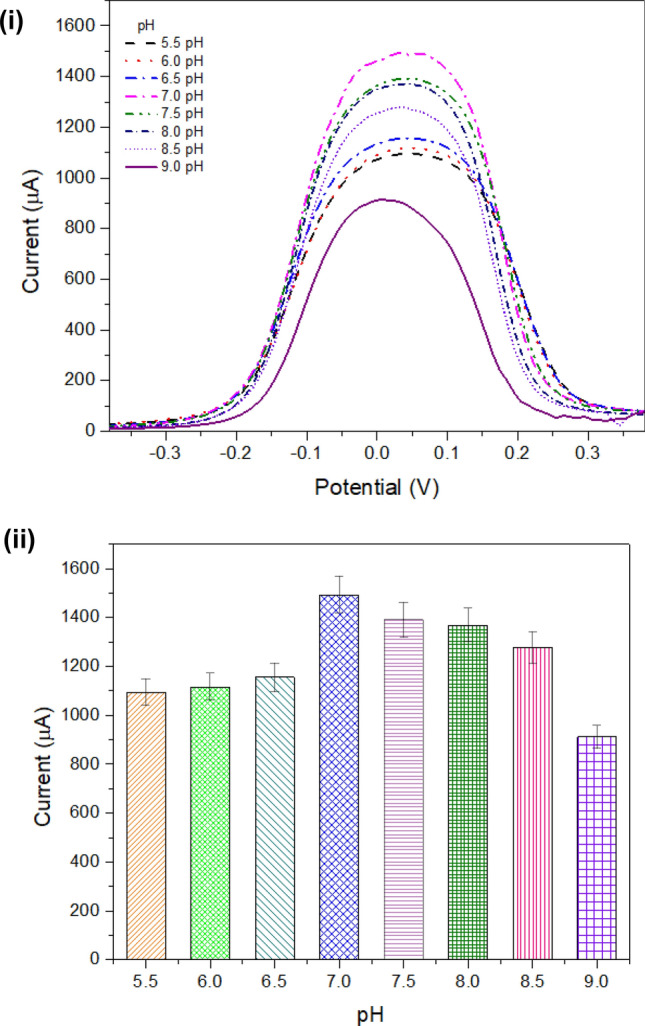

Evaluation of biosensor with varying pH

The electrode was examined with a solution of different pH samples of phosphate buffer from 5.5 to 9 pH with a difference of 0.5 pH units using the optimized concentration of TNF-α (0.01 pM). The SWV was recorded for the pH studies as shown in Fig. 7 (i). Taking into consideration the peak current of SWV response, a bar graph is plotted as shown in Fig. 7 (ii). The highest peak current was obtained with pH 7.0; hence, it was selected as the optimum pH for the developed biosensor (Yusof et al. 2013).

Fig. 7.

pH studies: (i) SWV measurement for evaluating electrode with different pH solutions within a range from 5.5 to 9.0 with an interval of 0.5; (ii) bar graph for peak current obtained with SWV measurements with different pH solutions

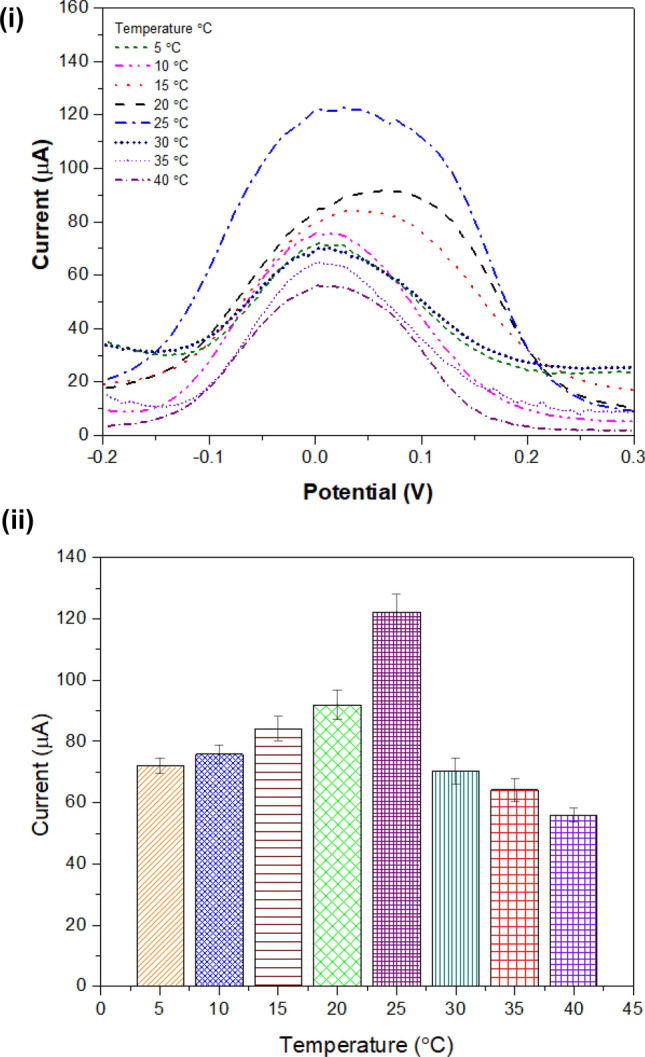

Determination of optimum temperature for the developed biosensor

The electrode was evaluated while differing temperature values from 5 to 40 °C with a difference at 5 °C unit. Figure 8 (i) demonstrates the DPV response at different temperatures. Further, a bar graph was plotted with peak current versus different temperature values as illustrated in Fig. 8 (ii). The graph defines that at temperature 25 °C, the electrode generated maximum peak current and thereafter decreases. Therefore, for further experimental work 25 °C was chosen as the optimum temperature. At higher temperatures, the hydrogen bonds present between protein and water molecules break down. This leads to the generation of higher resistance on the surface and resisting charge flow.

Fig. 8.

Evaluating electrode with different temperatures: (i) DPV studies for varying temperature within a range from 5 to 40 °C at an interval of 5 °C; (ii) bar representation for highest current observed with DPV studies at different temperatures

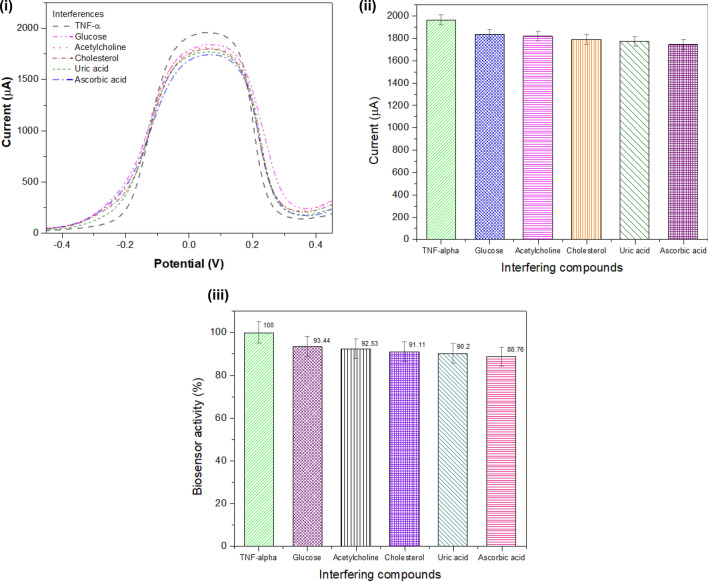

Interference studies for the biosensor

The SWV response of the working electrode was recorded with different interfering compounds such as glucose, acetylcholine, cholesterol, uric acid, and ascorbic acid as illustrated in Fig. 9 (i). The peak current obtained with SWV response was represented in the form of a bar graph in Fig. 9 (ii). The activity of the biosensor was calculated in % as shown in Fig. 9 (iii), with different interfering compounds glucose (93.44%), acetylcholine (92.53%), cholesterol (91.11%), uric acid (90.2%), and ascorbic acid (88.76%).

Fig. 9.

Interference studies: (i) SWV measurements for different interfering compounds such as glucose, acetylcholine, cholesterol, uric acid, and ascorbic acid; (ii) peak current obtained with SWV measurements for interference compounds; (iii) activity of biosensor obtained while adding various interfering compounds

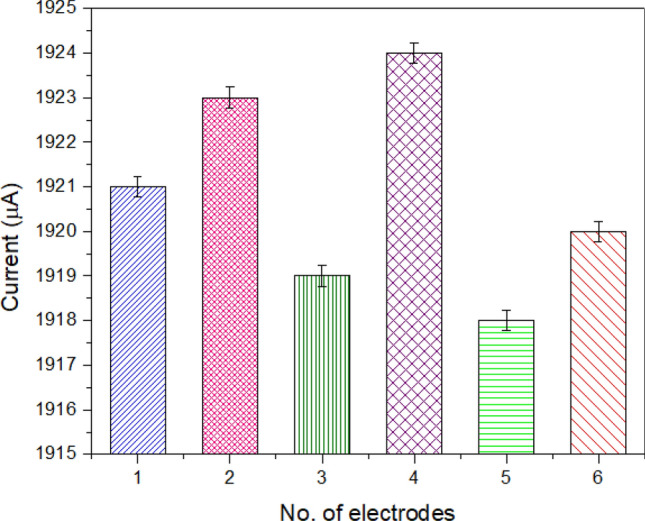

Repeatability and storage stability of the fabricated sensor

The experiment was repeated on six identically modified electrodes and electrochemical measurements were performed. The obtained results are illustrated in Fig. 10. The graph represents an average difference calculated with identical electrodes. The storage stability of the biosensor was studied while storing the electrode at 4 °C (dry condition) for 3 months. After 6 weeks, a 15% loss in the activity of the developed biosensor was observed from its original activity (100%).

Fig. 10.

Repeatability of electrode: evaluating six electrodes developed with similar conditions for checking the repeatability of data

Analytical performance of the developed sensing platform

The concentration range for optimization was obtained from 0.01 pM to 100 nM. The LOD of the biosensor was observed as 0.01 pM. The calculated response time of the developed sensor was less than 3 min. The optimized parameters for the present electrochemical biosensor are listed in Table 3. Various studies regarding the development of sensing platform for TNF-α has been reported in Table 1; however, these platforms have several limitations. On the other hand, this fabricated biosensor has various advantages over the reported sensors such as a wide detection range, lower LOD, high specificity, rapid detection, the low voltage required, less sample volume, and high sensitivity.

Table 3.

Summarizing the analytical parameters of the fabricated biosensor

| S. No | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Detection limit | 0.01 pM |

| 2 | Linear range | 0.01 pM–100 nM |

| 3 | Sample volume | 5 µL |

| 4 | Response time | < 3 min |

Discussion

This work demonstrates the assembling of a sensing platform for TNF-α in the case of neonatal sepsis. The platform was modified with MoS2NSs and Fe3O4@SiO2NPs, these nanostructures provide exceptional properties (large surface area, higher conductivity, and catalytic properties). Furthermore, the electrode was modified with an MIP to increase the specificity of the sensor. The SPE requires a low potential for operation, and less sample volume (50–100 μL) is needed for the analysis. This prepared biosensor facilitates the instant detection of the analyte (TNF-α). For developing the present biosensor, no complex steps are involved.

The MIPs were characterized with the BET technique to determine the surface area and diameter of the created pores. The biosensor operates in a detection range from picomolar level to nanomolar providing eminent sensitivity and specificity. The sensor was evaluated for different parameters (temperature, and pH) to determine the optimized conditions. The higher sensor response was obtained at pH 7 and 25 °C. Therefore, they were chosen as the optimum pH and temperature for the fabricated biosensor. There are different studies reported for the determination of TNF-α concentrations based on optical, piezoelectric, and electrochemical (Ghalehno et al. 2019; Pohanka, 2018; Rajeev et al. 2018; Bellagambi et al. 2017; Halima et al. 2021), but there are certain restrictions with these studies. This assembled biosensor overcomes the constraints of the reported studies while enhancing the conductivity, cost, time, and sensitivity of the biosensing platform. This developed biosensor exhibits a wide concentration range for detection, higher sensitivity, and a lower LOD that are found better than those in earlier reported literature. In the future, it can be developed into a miniaturized and portable device. This point-of-care (POC) device can be used at home for monitoring the health of the neonate. It can facilitate the early and rapid detection of sepsis in newborns. These kinds of developed biosensors have some limitations, such as the synthesis of MIP consumes a long time for preparation and also the extraction of molecules from MIP is a time-consuming process.

Conclusion

The presented work describes the development of an electrochemical biosensor for the identification of neonatal sepsis biomarkers (TNF-α). The biosensor is based on molecular imprinting of TNF-α. The sensing platform was modified with nanoparticles for better performance of the SPE. The electrode was coated with MoS2NSs, creating large active sites enhancing the charge transfer on the SPE. Further, the surface of the SPE was modified with Fe3O4@SiO2NPs providing a large surface area. Furthermore, the electrode was moderated with an MIP microsphere synthesized for TNF-α. The developed biosensor promised to provide highly sensitive and rapid results. The working range of the biosensor was determined from 0.01 pM to 100 nM and the rapid results are obtained within 3 min (response time). This developed biosensor exhibits a lower LOD of 0.01 pM. This developed biosensor can facilitate the early detection of neonatal sepsis and can be developed into a point-of-care device due to rapid results, lower LOD, and miniaturized size.

Abbreviations

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- EOS

Early-onset sepsis

- MoS2NSs

Molybdenum disulfide nanosheets

- Fe3O4@SiO2NPs

Silicon dioxide-modified iron oxide nanoparticles

- DPV

Differential pulse voltammetry

- MIPtemplate

Molecularly imprinted polymer with template

- LOS

Late-onset sepsis

- SPE

Screen-printed electrode

- HCl

Hydrochloric acid

- DW

Distilled water

- Fe3O4

Iron oxide

- NIP

Non-imprinted polymer

- SWV

Square wave voltammetry

- BET

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller

- CV

Cyclic voltammetry

- LOD

Limit of detection

Funding

The work was financially supported by the Extramural Research Grant (File No. EMR/2016/007564) and Young Scientist Scheme (File No. YSS/2015/000023) of the Science and Engineering Research Board, Government of India, and Technology Development Program (TDP) (TDP/BDTD/33/2019) of Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, and by Department of Biotechnology (DBT) (BT/PR36874/MED/97/475/2020), Government of India.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial or personal competing interest for the presented work.

Contributor Information

Ramesh Chandra, Email: acbrdu@hotmail.com.

Utkarsh Jain, Email: ujain@amity.edu, Email: karshjain@gmail.com.

References

- Adu AA, Neolaka YA, Riwu AAP, Iqbal M, Darmokoesoemo H, Kusuma HS. Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of swelling ratio on magnetic p53-poly (MAA-co-EGDMA)@ GO-Fe3O4 (MIP@ GO-Fe3O4)-based p53 protein and graphene oxide from kusambi wood (Schleichera oleosa) J Market Res. 2020;9:11060–11068. [Google Scholar]

- Balayan S, Chauhan N, Chandra R, Kuchhal NK, Jain U (2020) Recent advances in developing biosensing based platforms for neonatal sepsis. Biosens Bioelectron 112552 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bellagambi FG, Baraket A, Longo A, Vatteroni M, Zine N, Bausells J, Fuoco R, Di Francesco F, Salvo P, Karanasiou GS, Fotiadis DI. Electrochemical biosensor platform for TNF-α cytokines detection in both artificial and human saliva: heart failure. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2017;251:1026–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.05.169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SZ, Hollen SM, Cao L, Cui Y, Gupta JA, Gutiérrez HR, Heinz TF, Hong SS, Huang J, Ismach AF, Johnston-Halperin E. Progress, challenges, and opportunities in two-dimensional materials beyond graphene. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2898–2926. doi: 10.1021/nn400280c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan N, Pundir CS. An amperometric acetylcholinesterase sensor based on Fe3O4 nanoparticle/multi-walled carbon nanotube-modified ITO-coated glass plate for the detection of pesticides. Electrochim Acta. 2012;67:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan N, Narang J, Jain U. Amperometric acetylcholinesterase biosensor for pesticides monitoring utilising iron oxide nanoparticles and poly (indole-5-carboxylic acid) J Exp Nanosci. 2016;11:111–122. doi: 10.1080/17458080.2015.1030712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan N, Chawla S, Pundir CS, Jain U. An electrochemical sensor for detection of neurotransmitter-acetylcholine using metal nanoparticles, 2D material and conducting polymer modified electrode. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;89:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan N, Tiwari S, Jain U. Potential biomarkers for effective screening of neonatal sepsis infections: an overview. Microb Pathog. 2017;107:234–242. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domi B, Bhorkar K, Rumbo C, Sygellou L, Yannopoulos SN, Quesada R, Tamayo-Ramos JA. Fate assessment of commercial 2D MoS2 aqueous dispersions at physicochemical and toxicological level. Nanotechnology. 2020;31:445101. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aba6b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fojtů M, Teo WZ, Pumera M. Environmental impact and potential health risks of 2D nanomaterials. Environ Sci Nano. 2017;4:1617–1633. doi: 10.1039/C7EN00401J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghalehno MH, Mirzaei M, Torkzadeh-Mahani M. Electrochemical aptasensor for tumor necrosis factor α using aptamer–antibody sandwich structure and cobalt hexacyanoferrate for signal amplification. J Iran Chem Soc. 2019;16:1783–1791. doi: 10.1007/s13738-019-01650-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halima HB, Bellagambi FG, Alcacer A, Pfeiffer N, Heuberger A, Hangouët M, Zine N, Bausells J, Elaissari A, Errachid A. A silicon nitride ISFET based immunosensor for tumor necrosis factor-alpha detection in saliva. A promising tool for heart failure monitoring. Anal Chim Acta. 2021;1161:338468. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.338468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain U, Khanuja M, Gupta S, Harikumar A, Chauhan N. Pd nanoparticles and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) integrated sensing platform for the detection of neuromodulator. Process Biochem. 2019;81:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2019.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain U, Soni S, Balhara YPS, Khanuja M, Chauhan N. Dual-layered nanomaterial-based molecular pattering on polymer surface biomimetic impedimetric sensing of a bliss molecule, anandamide neurotransmitter. ACS Omega. 2020;5:10750–10758. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c00285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YS, Risbud S, Rabolt JF, Stroeve P. Synthesis and characterization of nanometer-size Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 particles. Chem Mater. 1996;8:2209–2211. doi: 10.1021/cm960157j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korzeniowska B, Nooney R, Wencel D, McDonagh C. Silica nanoparticles for cell imaging and intracellular sensing. Nanotechnology. 2013;24:442002. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/24/44/442002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahcen AA, Arduini F, Lista F, Amine A. Label-free electrochemical sensor based on spore-imprinted polymer for Bacillus cereus spore detection. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2018;276:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CW, Suh JM, Jang HW. Chemical sensors based on two-dimensional (2D) materials for selective detection of ions and molecules in liquid. Front Chem. 2019;7:708. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Xu W, Zhao X, Huang Y, Kang J, Qi Q, Zhong C. Electrochemical sensors based on molecularly imprinted polymers on Fe3O4/graphene modified by gold nanoparticles for highly selective and sensitive detection of trace ractopamine in water. Analyst. 2018;143:5094–5102. doi: 10.1039/C8AN00993G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes F, Pacheco JG, Rebelo P, Delerue-Matos C. Molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor prepared on a screen printed carbon electrode for naloxone detection. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2017;243:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2016.12.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lv B, Huang J, Yuan H, Yan W, Hu G, Wang J. Tumor necrosis factor-α as a diagnostic marker for neonatal sepsis: a meta-analysis. Sci World J. 2014;2014:471463. doi: 10.1155/2014/471463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohanka M. Piezoelectric biosensor for the determination of tumor necrosis factor alpha. Talanta. 2018;178:970–973. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L, Tang X, Wang Z, Peng X. Pore characterization of different types of coal from coal and gas outburst disaster sites using low temperature nitrogen adsorption approach. Int J Min Sci Technol. 2017;27:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmst.2017.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajeev G, Xifre-Perez E, Simon BP, Cowin AJ, Marsal LF, Voelcker NH. A label-free optical biosensor based on nanoporous anodic alumina for tumour necrosis factor-alpha detection in chronic wounds. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2018;257:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.10.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat B, Mishra KK, Barman U, Arora L, Pal D, Paily RP. Two-dimensional MoS 2-based electrochemical biosensor for highly selective detection of glutathione. IEEE Sens J. 2020;20:6937–6944. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2020.2978275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanaeifar N, Rabiee M, Abdolrahim M, Tahriri M, Vashaee D, Tayebi L. A novel electrochemical biosensor based on Fe3O4 nanoparticles-polyvinyl alcohol composite for sensitive detection of glucose. Anal Biochem. 2017;519:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shane AL, Sánchez PJ, Stoll BJ. Neonatal Sepsis. Lancet. 2017;390:1770–1780. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D, Farahbakhsh N, Shastri S, Sharma P. Biomarkers for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: a literature review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1646–1659. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1322060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AP, Balayan S, Gupta S, Jain U, Sarin RK, Chauhan N. Detection of pesticide residues utilizing enzyme-electrode interface via nano-patterning of TiO2 nanoparticle and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) nanosheets. Process Biochem. 2021;108:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2021.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Li J, Wang Y, Ding C, Lin Y, Sun W, Luo C. A chemiluminescence biosensor based on the adsorption recognition function between Fe3O4@SiO2@GO polymers and DNA for ultrasensitive detection of DNA. Spectrochim Acta Part A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2017;178:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2017.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang M, Wang L, Li W, Zheng J, Xu J. Synthesis of hierarchical nickel anchored on Fe3O4@SiO2 and its successful utilization to remove the abundant proteins (BHb) in bovine blood. New J Chem. 2015;39:4876–4881. doi: 10.1039/C5NJ00241A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HH, Chen XJ, Li WT, Zhou WH, Guo XC, Kang WY, Kou DX, Zhou ZJ, Meng YN, Tian QW, Wu SX. ZnO nanotubes supported molecularly imprinted polymers arrays as sensing materials for electrochemical detection of dopamine. Talanta. 2018;176:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen W, Song Y, Yan X, Zhu C, Du D, Wang S, Asiri AM, Lin Y. Recent advances in emerging 2D nanomaterials for biosensing and bioimaging applications. Mater Today. 2018;21:164–177. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2017.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn JL, Wong HR, Shanley TP, Bizzarro MJ, Saiman L, Polin RA. Time for a neonatal–specific consensus definition for sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:523. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Ji XF, Cao WQ, Wang J, Zhang Q, Zhong TL, Wang Y. Molecularly imprinted polymer based sensor directly responsive to attomole bovine serum albumin. Talanta. 2019;196:402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.12.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Xu H, Zhang D, Chen S. Synthesis of bilayer MoS2 nanosheets by a facile hydrothermal method and their methyl orange adsorption capacity. Mater Res Bull. 2014;55:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2014.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yücebaş BB, Yaman YT, Bolat G, Özgür E, Uzun L, Abaci S. Molecular imprinted polymer based electrochemical sensor for selective detection of paraben. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2020;305:127368. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2019.127368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yusof NA, Rahman SKA, Hussein MZ, Ibrahim Preparation and characterization of molecularly imprinted polymer as SPE sorbent for melamine isolation. Polymers. 2013;5:1215–1228. doi: 10.3390/polym5041215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Yao Y, Li X, Lan L, Jiang C, Ping J. Metallic transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets as an effective and biocompatible transducer for electrochemical detection of pesticide. Anal Chem. 2018;90:11658–11664. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Yao Y, Jiang C, Shao Y, Barceló D, Ying Y, Ping J. Self-reduction bimetallic nanoparticles on ultrathin MXene nanosheets as functional platform for pesticide sensing. J Hazard Mater. 2020;384:121358. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.