Abstract

Background

Glass ionomer cement is very popular in clinical practice due to their antibacterial and cariostatic properties, which is totally dependant on the amount of fluoride release and uptake by dentine. The short-term and long-term fluoride uptake by dentine from commercially available restorative materials like nano-ionomer, zirconia reinforced glass ionomer cement and flowable composite is of clinical interest.

Objective

To evaluate and compare Nano-ionomer, Zirconia reinforced glass ionomer, and flowable composite resin for the fluoride uptake by dentin at different time intervals.

Results

One–way ANOVA (Tukey-Kramer Multiple Comparison Test) was applied to test the comparison of mean values of all parameters compared together. The student's paired ‘t’ test was applied to compare groups. The fluoride uptake was evaluated at 3 days and 42 days. At 3 days dentin showed higher fluoride uptake with Zirconomer (Group Z) as compared to Ketac N100 and SDR Composite which was statistically significant. At 42 days higher fluoride uptake was seen in Ketac N100 (Group K) as compared to Zirconomer and SDR composite which was also statistically significant.

Conclusion

Fluoride uptake by dentine was seen in all study materials. Fluoride uptake by dentine at 3 days was seen maximum in Zirconomer, whereas fluoride uptake at 42 days was more in Ketac N100.

Keywords: Dentin uptake, Flowable composite, Fluoride, Nano-ionomer, Zirconomer

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Dental caries is one of the most common diseases affecting humans causing discomfort and pain if left untreated. A large population of people including both adults and children is affected by the disease leading to carious permanent and deciduous teeth respectively.1 It is a well-known fact that dental caries is the result of plaque accumulation and conversion of free sugars from various sources into acids that destroy tooth structure. Lack of fluoride exposure also increases the susceptibility to the disease.

Restoration of dental caries not involving pulp is the treatment of choice but in several cases, this restoration fails and causes further tooth damage. The primary reason for the failure of restoration is secondary caries in both permanent and primary dentition.2, 3, 4 The incorporation of fluoride in dental materials makes them more caries resistant.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Fluoride interacts with calcium hydroxyapatite crystals of the mineralized portion of the tooth forming calcium fluorapatite, thereby reducing demineralization of the tooth as fluorapatite is more resistant to caries than hydroxyapatite. Fluoride also aids in remineralization hence the anti-cariogenic property of dental materials is determined by the quantity of fluoride content present.12

The current fluoride-releasing restorative dental materials include RMGIC, glass-ionomers, polyacid-modified composites (compomers), amalgams, and composites.13 Initially, Glass Ionomer Cement (GIC) releases a large quantity of fluoride, followed by a decrease in the fluoride concentration which remains consistent thereafter.14, 15, 16 The fluoride release and recharge of GICs are better than other available restorative materials, i.e. compomers and resin composites.8 The problems of moisture sensitivity and low initial mechanical strengths were improved with the advent of materials like compomers and RMGIC that have both fluoride release properties from conventional GIC and esthetic properties from composites.

Recently introduced nanomaterial Ketac N100 has better optical properties, fine texture and can be easily polished.17 The fluoroaluminosilicate (FAS) of this nano-ionomer reacts with acrylic and itaconic acid copolymers. Resin monomers, bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate (Bis GMA), triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA), polyethylene glycol dimethacrylate (PEGDMA), and hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) in the reaction mixture polymerize via free radical addition polymerization. Two-thirds of the filler content of glass ionomer cement contains nano-fillers. Nano-sized glass particles and clusters of nanosilica particles improve their physical properties. Due to its increased surface area to volume ratio, nano-sized filler, provide a quicker release of fluoride.18

Zirconomer a new restorative material was launched by Shofu which is a zirconia reinforced Glass Ionomer. The main advantage of this material is its strength and longevity. Zirconia is being used as indirect restorative material since 1998. Zirconia is mainly used for crown and bridge restoration due to its better strength.

Smart Dentin Replacement SDR™ is also a recently introduced flowable composite that has decreased the stress of composite systems and it was termed as smart dentin replacement. The components of SDR™ are a combination of SDR™, filled resins, and other materials. The major advantages of using SDR were bulk-filled flowable base and high amounts of fluoride release.19

Fluoride release of the material varies due to the dissimilar matrices and setting process.20 There is negligible documented literature on fluoride uptake by dentin from various restorative materials. Thereby the purpose of the study was to evaluate Nano-ionomer, Zirconia reinforced glass ionomer, and flowable composite resin for the fluoride uptake by dentin at different time intervals.

2. Materials and methods

The present study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (DYPDCH/1126/2014).

The inclusion criteria of the study included freshly extracted intact healthy human premolar teeth including both maxillary and mandibular premolars. While the exclusion criteria excluded carious teeth, cracked teeth/fractured teeth, hypoplastic teeth, restored teeth, attrited, eroded, and abraded teeth, deciduous teeth, and teeth with developmental anomalies.

The study included twenty-one healthy, noncarious human premolar teeth extracted due to orthodontic reasons. Informed consent was obtained from the patients for use of the extracted tooth material for research. Teeth with developmental anomalies, attrition, abrasion, erosion, restoration, fracture, or hypoplasia were excluded from the study. The extracted teeth were immediately washed, cleaned with an ultrasonic scaler, and stored in water until further experimentation.

The specimens were divided into 4 Experimental study groups as follows:-

-

1.

Group A – Control without any restorative material. (n = 3 teeth, 6 sections).

-

2.

Group K – Fluoride uptake from Ketac N100. (n = 6 teeth, 12 sections).

-

3.

Group Z – Fluoride uptake from Zirconomer (n = 6 teeth, 12 sections).

-

4.

Group C – Fluoride uptake from SDR flowable Composite (n = 6 teeth, 12 sections).

Each group was further subdivided into two depending on the time of evaluation.

-

•

Group A – Control without any restorative material (n = 3 teeth, 6 sections)

-

•

Group K1 – Fluoride uptake from Ketac N100 at 3 days (n = 3 teeth, 6 sections)

-

•

Group K2 – Fluoride uptake from Ketac N100 at 42 days (n = 3 teeth, 6 sections)

-

•

Group Z1 – Fluoride uptake from Zirconomer at 3 days. (n = 3 teeth, 6 sections)

-

•

Group Z2 – Fluoride uptake from Zirconomer at 42 days (n = 3 teeth, 6 sections)

-

•

Group C1 – Fluoride uptake from SDR flowable Composite at 3 days. (n = 3 teeth; 6 sections)

-

•

Group C2 – Fluoride uptake from SDR flowable Composite at 42 days (n = 3teeth; 6 sections)

Products/equipment/instruments used in the study along with their manufacturer are as follows:

Airotor handpiece (NSK, Japan), Straight handpiece (NSK, Japan), Kidney tray.

Materials used: Nano Ionomer cement (Ketac N 100, 3 M ESPE), Reinforced Glass Ionomer cement (Zirconomer, SHOFU), Flowable Composite Resin (SDR, DENTSPLY), Etchant (Prime Dental), Primer (3 M ESPE), Bonding agent (Prime & Bond NT, DENTSPLY), Distilled water.

Equipment used: Ultrasonic scaler (EMS SA CH-1260 Nyon AT 16786, Minipiezon), Light curing unit (Confident), Humidifier (Classic Scientific), SEM with Image Analyser Software (EDAX-QUANTA 200.

2.1. Cavity preparation

Class I cavities measuring 5 mm × 3 mm x 2 mm were made with round and straight burs. Cavity dimensions were confirmed using a graduated probe.

2.2. Restoration

-

•

The composition of the restorative materials is depicted in Table 1. The respective restorative materials were mixed as per the manufacturer's directions and laid down in the prepared cavities. These materials were then cured using an Elipar 2500 (3 M ESPE, St Paul, MN, USA) halogen curing unit. Before the study and before each specimen was cured, the intensity of the curing light source was checked with a radiometer. The specimens were cured as per the manufacturers' directions i.e. for 20 s. The flowable composite was light-cured for 40 s. All specimens were stored in a humidifier until the time of evaluation at 3 days and 42 days (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Summary of the materials used in the study.

| Material | Composition | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| Group K - Nano-ionomer | Paste A: Fluoroaluminosilicate glass, silane-treated silica and, nanofillers, methacrylate and dimethacrylate resins, and photoinitiators Paste B: Polyalkenoic acid copolymer silane-treated zirconia silica nanoclusters, silane-treated silica nanofiller, and hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

Ketac N 100, 3 M ESPE |

| Group Z – Zirconia reinforced Glass Ionomer Cement | Powder: Fluroaluminosilicate glass, Zirconium oxide, Tartaric acid, pigment and others | Zirconomer, Shofu |

| Group C – Flowable composite | Ethoxylated Bisphenol A dimethacrylate(EBPADMA); Triethyleneglycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA); Modified urethane dimethacrylate resin Camphorquione(CQ); Photoinitiator; Butylated hydroxyl toluene (BHT); Barium- alumino-fluoro-borosilicate glass; Strontium alumino-fluoro-silicate glass; Titanium dioxide; Iron oxide pigments | SDR flowable composite Dentsply |

Fig. 3.

Tooth samples, Cavity preparation, and restoration with the help of light-curing.

2.3. Evaluation for fluoride uptake

Three teeth from each subgroup 1 (K1, Z1, C1) were sectioned at 3 days, and subgroup 2.

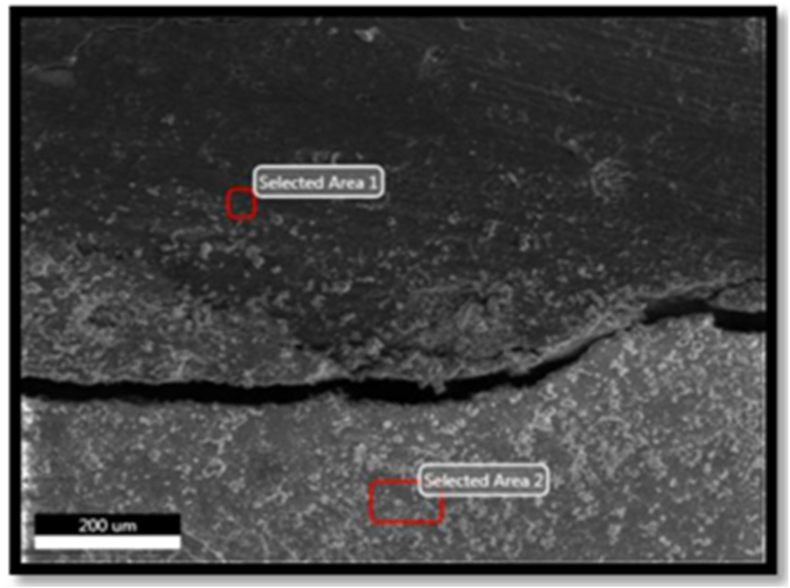

(K2, Z2, C2) were sectioned after 42 days for all three restorative materials. Each sample was longitudinally sectioned into two halves using a disc, thus obtaining 6 sections in each subgroup. They were then assessed for fluoride uptake by dentin under SEM using magnification of 500X21 EDAX (Energy Dispersive X-ray analysis) was conducted randomly to select spots containing fluoride in each group. The spot with maximum amount of fluoride was identified. The EDAX image analyser software was used to calculate the fluoride in dentine.

EDAX is a standard method with the help of which elemental compositions are identified and quantified. Electron beams excite the surface atoms and the resulting X-rays emitted tells us about the characteristics of the specific specimens (Fig. 4).22

Fig. 4.

SEM and EDAX analysis for quantifying fluorine concentration in the specimen.

2.4. Statistical analysis

One–way ANOVA test (Tukey-Kramer Multiple Comparison Test) was applied to test the comparison of mean values of all parameters compared together. To compare groups, Student's Paired ‘t’ test was used.

3. Results

At 42 days Ketac N100 (Group K) exhibited a highly significant increase in Fluoride uptake by dentine compared to 3 days. While Zirconomer (Group Z) and SDR Flowable Composite (Group C) demonstrated a significant decrease in Fluoride uptake at 42 days compared to 3 days. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of mean and SD values of Fluoride uptake by dentine in all groups at 3 days and 42 days.

| Flouride uptake by dentine (n = 6) | 3 days |

42 days |

Student's paired ‘t’ test value | ‘p’ value and significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Group A – Control without any restorative material | 0.93 ± 0.14 | 0.93 | p = 0.789 not significant |

|

| Group K – Fluoride uptake by dentin from KETAC N100 | 2.24 ± 0.48 | 3.64 ± 0.31 | 4.34 | p = 0.0001 highly significant |

| Group Z – Fluoride uptake by dentin from ZIRCONOMER | 10.06 ± 2.18 | 3.34 ± 0.30 | 13.28 | p = 0.0001 highly significant |

| Group C – Fluoride uptake by dentin from SDR Composite | 2.65 ± 0.13 | 1.55 ± 0.25 | 14.18 | p = 0.0001 highly significant |

At 3 days Zirconomer (Group Z) had the highest fluoride uptake (10.06 ± 2.18) followed by SDR Flowable Composite (2.65 ± 0.13) and Ketac N100 (2.24 ± 0.48). The results were statistically significant (Table 2 and Fig. 1). At 42 days Ketac N100 (Group K) demonstrated the highest fluoride uptake (3.64 ± 0.31) followed by Zirconomer (3.34 ± 0.30) and SDR Flowable Composite(1.55 ± 0.25). (Table 2 and Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of mean values of fluoride uptake by dentin in all groups at 3 days.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of mean values of fluoride uptake by dentin in all groups at 42 days.

4. Discussion

GIC was first introduced as a dental restorative material by Wilson and Kent in 1972. It chemically bonds to dentin as well as enamel with non-significant development of heat or shrinkage.23 It shows biocompatibility with the dental pulp and periradicular structures, ultimately leading to fluoride release and causing caries resistant and anti-microbial activity.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Many authors have illustrated the efficacy of GIC for the evaluation of fluoride content in enamel as well as in dentin24, 25, 26. However, this material is weak considering withstanding masticatory forces.27

Developments in conventional GIC formulation led to the introduction of RMGIC and compomers with superior physical and mechanical properties while maintaining its fluoride-releasing property. These materials are easy to handle, have less setting time, have higher strength, and wear resistance.11,28 Various studies done by researchers have demonstrated that levels of fluoride discharge from RMGIC & compomer were much higher when compared with composites.12,29, 30, 31 However, a few studies reported no notable dissimilarity in fluoride release from RMGIC and conventional GIC.32, 33, 34 Y Dziuk et al. showed that the resin-modified GIC released more fluoride compared with conventional GIC.35 Various other studies have shown increased,31 same,15,34 and decreased release rates of fluoride release36 for conventional GICs when contrasted with RMGICs. The nano-sized filler releases fluoride in the powder early attributing to the increased surface area to volume, ultimately leading to an increase in fluoride release of the material. It has been illustrated that for higher acid-base reactivity and large surface area, the glass particles should be small. This speeds up the liberation of fluoride from the powder and hence shows increased fluoride release.12,31

Recently flowable composite resins have also gained tremendous popularity. They are generally used for restoring small Class I, II, and Class III cavities, as a liner or base below packable composite resin in Class IIcavties, Class V cavities, Class VI cavities in non-stress bearing areas, and splinting fractured and mobile teeth.

Ketac N100 a recently introduced nanomaterial has better optical properties and Zirconomer is also a new material with high strength. Despite the several advantages of these materials, the fluoride release property plays a vital role in determining the success of the restoration as it prevents secondary caries. To the best of our knowledge, there is no documented literature concerning fluoride uptake in dentine, particularly from these newer materials namely nano-ionomer (Ketac N100), Zirconomer, and flowable composite resin (SDR). Hence the present study was conducted to assess and compare Nano-ionomer, Zirconia reinforced glass ionomer, and flowable composite resin for the fluoride uptake by dentin at 3 days and 42 days.

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) is currently used for high magnification imaging of almost all materials. EDAX (Energy-dispersive analysis of x-rays) is a reproducible, reliable, and precise technique to identify and quantify major components present in a material. Hence, in this study SEM with EDAX was used to measure fluoride uptake by dentin. At 500 X a field was randomly selected for evaluation of the specimen.

In the present study Zirconomer at 3 days demonstrated the highest fluoride uptake. The burst effect seen in Zirconomer evaluated at 3 days may attribute to the greater solubility of this chemical or self-cure material which is set by acid-base reaction only, unlike Ketac N100 and SDR Composite which are set by a polymerization reaction and are less soluble. Bertolini et al. in 2009 reported that Zirconia-reinforced samples demonstrated low fluoride release value after 24 h to an increased value after 7 days which again degraded after 28 days. Vermeersch et al. in 2001; Attar and Turgut in 2003 and Wiegand et al. in 2007 found that the peak release occurs at beginning of 24 h pursued by a low, prolonged elution which is concurrent with the present study.12,31,37

Forsten et al. in 1977 proposed the pattern of fluoride release,38 showed that there is peak release of fluoride in the first 24 h and later on drops gradually by end of 3 months and traced up to 2 years.39,40 Due to the beginning of the ‘wash-off of fluoride from the cement surface, there is a release of initial fluoride burst. Later, the cement controls the fluoride dissolution rate. The surface area available for dissolution governs the rate of dissolution and is independent of the shape of the sample and the solution.

Considering studies that have assessed the fluoride release by GIC, studies by Bertolini et al. in 2009 and Perrin et al.in 199441 reported the highest release of Fluoride from GIC on the first day and reduced eventually.42 Initially, fluoride release from Glass ionomer cement is in large quantities followed by consistent release over a longer period as concluded by Zafar MS et al., Momoi Y et al. and. Mitra SB.14, 15, 16 However, KetacMolar demonstrated a highly significant increase in Fluoride uptake at 42 days in comparison with 3 days as well as in comparison with Zirconomer and flowable composite resin (SDR) at 42 days. Paschoal et al.43 reported that nanoparticulated GIC shows the less but steady release of fluoride which is following the present study. As fluoride reduces the translucency of the material, the initial amount of fluoride added to the material is compromised by the manufacturer due to which a low release of fluoride is observed from the glass ionomer cement. The acid-base reactions between fluoride-containing glasses and polyacid liquid cause fluoride release of conventional glass-ionomer cement. This causes a surplus discharge of ions in the initial days as it sets.

In the present study, the fluoride release from the SDR composite was the least at 42 days in comparison with Ketac molar and Zirconomer. The results are concurrent with the findings of Francci C et al.44 and Glasspoole EA.45 Fluoride-filled filler particles lead to the passive leaching of fluoride.44,45 The less amount of fluoride incorporated, less solubility in water, less water content of the material and lesser permeability of the resin adds to the reasons for low fluoride release.45

The limitations of this study are that the study has an in-vitro design and has to be replicated in the clinical scenario. The evaluation of Fluoride using EDAX analysis was carried out at random spots. Lastly, there may be inherent fluoride in the tooth structure which should be considered during evaluation.

5. Conclusion

Within the limitations of the study it can be concluded that Ketac N100 demonstrated the highest fluoride uptake by dentine at 3 days and Zircomonomer demonstrated the highest fluoride uptake by dentine at 42 days. Future clinical studies in this regard have to be carried out to demonstrate the fluoride release of the newer materials. Hence the choice of dental materials for restoration should be made by the clinician after a thorough knowledge of the fluoride release to prevent secondary caries and ensure longevity and success of the restorations.

Contributor Information

Sanjyot Mulay, Email: sanjyot.mulay@dpu.edu.in.

Kunal Galankar, Email: kunal_galankar@yahoo.com.

Saranya Varadarajan, Email: vsaranya87@gmail.com.

Archana A. Gupta, Email: archanaanshumangupta@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Mungara J., Philip J., Joseph E., Rajendran S., Elangovan A., Selvaraju G. Comparative evaluation of fluoride release and recharge of pre-reacted glass ionomer composite and nano-ionomeric glass ionomer with daily fluoride exposure: an in vitro study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2013;31:234–239. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.121820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Taee L., Banerjee A., Deb S. An integrated multifunctional hybrid cement (pRMGIC) for dental applications. Dent Mater. 2019;35:636–649. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasan A.M.H.R., Sidhu S.K., Nicholson J.W. Fluoride release and uptake in enhanced bioactivity glass ionomer cement (“glass carbomerTM") compared with conventional and resin-modified glass ionomer cements. J Appl Oral Sci. 2019;27 doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dionysopoulos P., Kotsanos N., Koubia Koliniotou, Papagodiannis Y. Secondary caries formation in vitro around fluoride-releasing restorations. Operat Dent. 1994;19:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Godoy F., Olsen B.T., Marshall T.D., Barnwell G.M. Fluoride release from amalgam restorations lined with a silver-reinforced glass ionomer. Am J Dent. 1990;3:94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souto M., Donly K.J. Caries inhibition of glass ionomers. Am J Dent. 1994;7:122–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawls H.R., Zimmerman B.F. Fluoride-exchanging resins for caries protection. Caries Res. 1983;17:32–43. doi: 10.1159/000260646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skartveit L., Tveit A.B., Ekstrand J. Fluoride release from a fluoride‐containing amalgam in vivo. Eur J Oral Sci. 1985;93:448–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1985.tb01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsten L. Fluoride release and uptake by glass ionomers. Eur J Oral Sci. 1991;99:241–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1991.tb01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hse K.M.Y., Leung S.K., Wei S.H.Y. Resin-ionomer restorative materials for children: a review. Aust Dent J. 1999;44:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1999.tb00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Featherstone J.D.B. The science and practice of caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:887–899. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke F.J., Cheung S.W., Mjör I.A., Wilson N.H. Reasons for the placement and replacement of restorations in vocational training practices. Prim Dent Care. 1999;6:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.R F., DF V., SM Z. Fluoride release and physical properties of a fluoride-containing amalgam. J Prosthet Dent. 1977;38:526–531. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(77)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cildir S.K., Sandalli N. Compressive strength, surface roughness, fluoride release and recharge of four new fluoride-releasing fissure sealants. Dent Mater J. 2007;26:335–341. doi: 10.4012/dmj.26.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Retief D.H., Bradley E.L., Denton J.C., Switzer P. Enamel and cementum fluoride uptake from a glass ionomer cement. Caries Res. 1984;18:250–257. doi: 10.1159/000260773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forss H., Seppä L. Prevention of enamel demineralization adjacent to glass ionomer filling materials. Eur J Oral Sci. 1990;98:173–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1990.tb00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen P.E. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century - the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:3–24. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shashikiran N.D., Kumar N.C., Subba Reddy V.V. Fluoride uptake by enamel and dentin from bonding agents and composite resins: a comparative study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2003;21:125–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell A., Creanor S.L., Foye R.H., Saunders W.P. The effect of saliva on fluoride release by a glass-ionomer filling material. J Oral Rehabil. 1999;26:407–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.1999.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.R W. Liners and bases in general dentistry. Aust Dent J. 2011;56(Suppl 1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/J.1834-7819.2010.01292.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Özveren N., Özalp S. Microhardness and SEM-EDX analysis of permanent enamel surface adjacent to fluoride-releasing restorative materials under severe cariogenic challenges. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2018;16:417–424. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a41363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Son D., Cho S., re kr, Nam J., Lee H., Kim M. X-ray-based spectroscopic techniques for characterization of polymer nanocomposite materials at a molecular level. Polymers (Basel) 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/POLYM12051053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LF F., PM S., de B V.R., C M., PA F. Glass ionomer cements and their role in the restoration of non-carious cervical lesions. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:364–369. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000500003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mjör I.A., Toffenetti F. Secondary caries: a literature review with case reports. Quintessence Int. 2000;31:165–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buzalaf M.A.R., Pessan J.P., Honório H.M., Ten Cate J.M. Mechanisms of action of fluoride for caries control. Monogr Oral Sci. 2011;22:97–114. doi: 10.1159/000325151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ten Cate J.M. In vitro studies on the effects of fluoride on de- and remineralization. J Dent Res. 1990;69:614–619. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690s120. J Dent Res. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.GM K., JM M., None M. Bond strengths between composite resin and auto cure glass ionomer cement using the co-cure technique. Aust Dent J. 2006;51:175–179. doi: 10.1111/J.1834-7819.2006.TB00423.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiegand A., Buchalla W., Attin T. Review on fluoride-releasing restorative materials-Fluoride release and uptake characteristics, antibacterial activity and influence on caries formation. Dent Mater. 2007;23:343–362. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geurtsen W., Leyhausen G., Garcia-Godoy F. Effect of storage media on the fluoride release and surface microhardness of four polyacid-modified composite resins (“compomers”) Dent Mater. 1999;15:196–201. doi: 10.1016/S0109-5641(99)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geurtsen W., Bubeck P., Leyhausen G., Garcia-Godoy F. Effects of extraction media upon fluoride release from a resin-modified glass-ionomer cement. Clin Oral Invest. 1998;2:143–146. doi: 10.1007/s007840050060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behrend B., Geurtsen W. Long-term effects of four extraction media on the fluoride release from four polyacid-modified composite resins (compomers) and one resin-modified glass-lonomer cement. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;58:631–637. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abu-Bakr N.H., Han L., Okamoto A., Iwaku M. Effect of alcoholic and low-pH soft drinks on fluoride release from compomer. J Esthetic Restor Dent. 2000;12:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2000.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcez R.M.V.D.B., Buzalaf M.A.R., De Araújo P.A. Fluoride release of six restorative materials in water and pH-cycling solutions. J Appl Oral Sci. 2007;15:406–411. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572007000500006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markovic D.L., Petrovic B.B., Peric T.O. Fluoride content and recharge ability of five glassionomer dental materials. BMC Oral Health. 2008;8 doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Y D S.C., SC M., S T., EA N., G D. Fluoride release from two types of fluoride-containing orthodontic adhesives: conventional versus resin-modified glass ionomer cements-An in vitro study. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0247716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bansal R., Bansal T. A comparative evaluation of the amount of fluoride release and Re-release after recharging from aesthetic restorative materials: an in vitro study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:ZC11–Z14. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11926.6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedrini D., Delbem A.C.B., de França J.G.M., Machado T. de M. Fluoride release by restorative materials before and after a topical application of fluoride gel. Pesqui Odontol Bras. 2003;17:137–141. doi: 10.1590/S1517-74912003000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritter A.V., Walter R., Boushell L.W. Sturdevant's art and science of operative dentistry. 2018. [DOI]

- 39.Vermeersch G., Leloup G., Vreven J. Fluoride release from glass-ionomer cements, compomers and resin composites. J Oral Rehabil. 2001;28:26–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Attar N., Önen A. Fluoride release and uptake characteristics of aesthetic restorative materials. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29:791–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lobo M.M., Pecharki G.D., Tengan C., da Silva D.D., da Tagliaferro E.P.S., Napimoga M.H. Fluoride-releasing capacity and cariostatic effect provided by sealants. J Oral Sci. 2005;47:35–41. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.47.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelić K., Par M., Peroš K., Šutej I., Tarle Z. Fluoride-releasing restorative materials: the effect of a resinous coat on ion release. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2020;54:371–381. doi: 10.15644/asc54/4/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chatzistavrou E., Eliades T., Zinelis S., Athanasiou A.E., Eliades G. Fluoride release from an orthodontic glass ionomer adhesive in vitro and enamel fluoride uptake in vivo. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:458. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.10.030. e1-458.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neelakantan P., John S., Anand S., Sureshbabu N., Subbarao C. Fluoride release from a new glass-ionomer cement. Operat Dent. 2011;36:80–85. doi: 10.2341/10-219-LR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paschoal M.A., Gurgel C.V., Rios D., Magalhães A.C., Buzalaf M.A., Machado M.A. Fluoride release profile of a nanofilled resin-modified glass ionomer cement. Braz Dent J. 2011;22(4):275–279. doi: 10.1590/S0103-64402011000400002. PMID: 21861024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]