Abstract

Although ocular toxoplasmosis is usually a self-limiting infection, it can lead to severe reduction in visual acuity due to intense vitreous inflammation or involvement of posterior segment structures. Depending on the severity of intraocular inflammation, serious complications, including epiretinal membrane or retinal detachment may develop. In this paper, we aim to present a case that complicated by both a full-thickness macular hole and retinal detachment secondary to toxoplasmosis chorioretinitis that developed shortly after the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and discuss our treatment approach. After the patient was diagnosed based on a routine ophthalmological examination, fundus imaging, and serological examination, functional and anatomical recovery was achieved through systemic antibiotherapy and vitreoretinal surgery. Full-thickness macular hole and retinal detachment are rare complications of ocular toxoplasmosis. However, there are only few publications in the literature concerning these complications and their surgical treatment. In this case report, we demonstrated the success of vitreoretinal surgery combined with antibiotic therapy on the posterior segment complications of ocular toxoplasmosis.

Keywords: Toxoplasma, Ocular toxoplasmosis, Macular hole, Retinal detachment, COVID-19

Résumé

Bien que la toxoplasmose oculaire soit généralement une infection spontanément résolutive, elle peut entraîner une réduction sévère de l’acuité visuelle en raison d’une inflammation intense du vitré ou d’une atteinte des structures du segment postérieur. Selon la gravité de l’inflammation intraoculaire, des complications graves, notamment la membrane épirétinienne ou le décollement de la rétine, peuvent se développer. Dans cet article, nous visons à présenter un cas compliqué à la fois par un trou maculaire de pleine épaisseur et un clivage rétinien secondaire à une choriorétinite toxoplasmique qui s’est développée peu de temps après la nouvelle maladie à coronavirus (COVID-19) et des discussions sur notre approche thérapeutique. Après que le patient ait été diagnostiqué sur la base d’un examen ophtalmologique de routine, d’une imagerie du fond d’œil et d’un examen sérologique, la récupération fonctionnelle et anatomique a été obtenue grâce à une antibiothérapie systémique et à une chirurgie vitréorétinienne. Le trou maculaire de pleine épaisseur et le décollement de la rétine sont des complications rares de la toxoplasmose oculaire. Cependant, il existe peu de publications dans la littérature concernant ces complications et leur traitement chirurgical. Dans ce rapport de cas, nous avons démontré le succès de la chirurgie vitréorétinienne associée à une antibiothérapie sur les complications du segment postérieur de la toxoplasmose oculaire.

Mots clés: Toxoplasme, Toxoplasmose oculaire, Trou maculaire, Décollement de rétine, COVID-19

Introduction

Ocular toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of infectious uveitis worldwide and is caused by Toxoplasma gondii, an obligate intracellular parasite. Ocular toxoplasmosis is responsible for 28% of all posterior uveitis cases [1]. Acquired infection or re-exacerbation of congenital infection may be responsible for the development of these cases. The first complaints of these patients are usually unilateral floaters, blurred vision, and photophobia. The diagnosis is made clinically based on the observation of typical lesions in the fundus examination. Serology is also used to support the diagnosis and make a differential diagnosis [2], [3].

Although ocular toxoplasmosis is usually a self-limiting infection in immunocompetent individuals, it can lead to severe reduction in visual acuity due to intense vitreous inflammation or involvement of posterior segment structures. The typical presentation of the disease is focal necrotizing chorioretinitis, usually in one eye, which is adjacent to the old, pigmented scar and accompanied by vitritis. Posterior uveitis is often accompanied by granulomatous anterior uveitis. Depending on the severity of intraocular inflammation, serious complications, such as epiretinal membrane or retinal detachment may develop [1], [4].

In this paper, we present a case complicated by a full-thickness macular hole and retinal detachment secondary to toxoplasmosis chorioretinitis that developed shortly after the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and discuss our treatment approach.

Case report

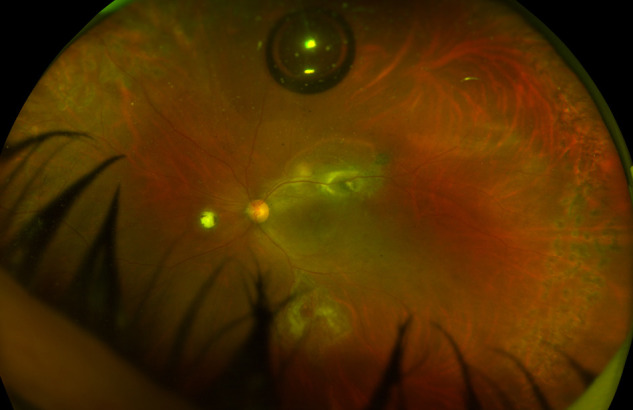

In May 2021, a 30-year-old female patient presented to the Ophthalmology Clinic of Health Sciences University Antalya Training and Research Hospital with acute-onset unilateral low vision. The patient's anamnesis revealed that she had tested positive for COVID-19 two weeks earlier. The patient was emmetrope and the visual acuity in the left eye was at the level of hand movement, and intraocular pressure was normal. Her ophthalmological examination showed +2 cells in the anterior chamber and +2 vitritis in the left eye. In the fundus examination, in addition to two toxoplasmosis-specific classical chorioretinitis scars, there was an area of active chorioretinitis adjacent to the superior temporal arcuate vessels, one of which was of 2/3 optic disc size and located in the nasal of the optic disc and the other was of 1 optic disc size and located adjacent to the superior temporal arcuate vessel. Additionally, no retinal tear or rhegmatogenic lesion was observed in the peripheral fundus examination of the patient. A full-thickness macular hole and secondary macula-off retinal detachment were also observed (Figure 1, Figure 2 ). The size of the full-thickness macular hole was 698 μm. Optomap wide-angle fundus imaging (Daytona, Optos®, UK), optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA, AngioVue; Optovue, Inc, Fremont, CA), and fundus fluorescein angiography were performed. To support the diagnosis and to make a differential diagnosis, serological tests were performed. According to the findings, anti-toxoplasma IgG antibody was positive (470,30 IU/L) and anti-toxoplasma IgM antibody was negative (0.288 IU/L). In addition, the laboratory tests showed that the patient was negative for anti-HIV, anti-Herpes, anti-Varicella and anti-CMV antibodies and VDRL-RPR. The patient was diagnosed with toxoplasma chorioretinitis and started on oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg) twice a day and clindamycin 300 mg four times a day. After three days, 32 mg/day methylprednisolone was added to oral treatment. The patient was hospitalized, and vitreoretinal surgery was scheduled for the treatment of the macular hole and retinal detachment.

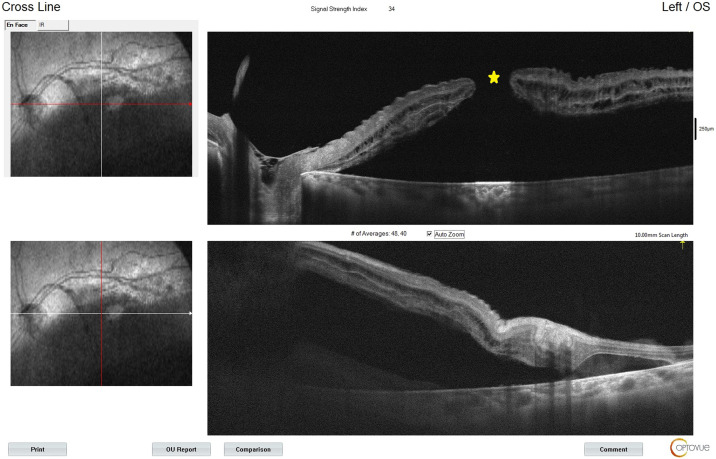

Figure 1.

Optomap wide-angle fundus imaging of the patient showing chorioretinitis areas (red arrows), a macular hole (yellow star), and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (blue arrow).

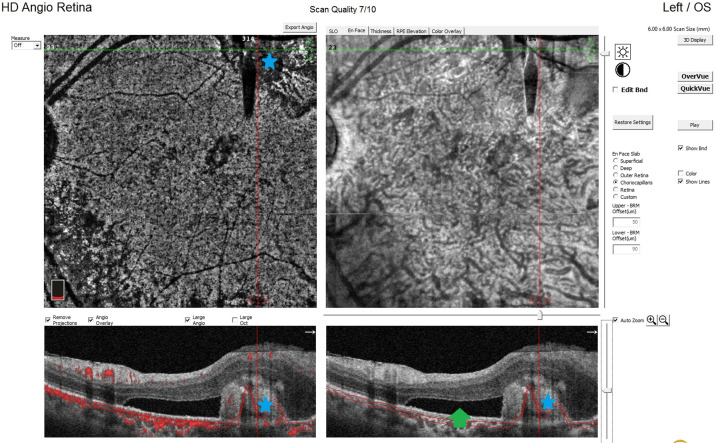

Figure 2.

Optical coherence tomography angiography imaging showing a full-thickness macular hole (yellow star) and retinal detachment.

Under general anesthesia, the patient underwent core vitrectomy with 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy (PPV). Then posterior hyaloid membrane peeling, and peripheral vitrectomy were performed using 0.8 mg/0.1 cc triamcinolone. After the internal limiting membrane (ILM) was visualized with ILM staining, it was peeled circularly from the fovea using 23-gauge microforceps under decaline. The peeled ILM piece was placed into the macular hole using the inverted flap technique. Subretinal fluid was drained with single retinotomy from the extramacular region, and the retina was completely reattached. Subsequently, 360-degree retinal photocoagulation was performed. Then, liquid-air and air-gas tamponade exchange was applied. As gas, 16% SF6 was used. Surgery was terminated after the trocar sites were sutured.

After surgery, the patient was placed in prone position for 10 days. Topically, drops containing antibiotics and steroids were applied for up to one month after surgery. Oral antibiotic treatment for toxoplasma was continued for six weeks.

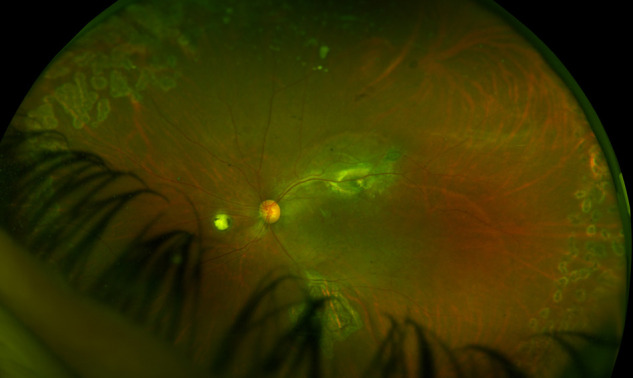

In the follow-up session undertaken on the 20th postoperative day, the visual acuity of the left eye was 20/400. Intraocular pressure was normal in both eyes, and no cells were observed in the anterior chamber. The retina was observed to be attached and the full-thickness macular hole was closed (Fig. 3 ). In OCTA imaging, secondary choroidal neovascularization (CNV) and subretinal fluid were detected in the old scar area adjacent to the active chorioretinitis (Fig. 4 ), and one dose of intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agent was administered to the same eye.

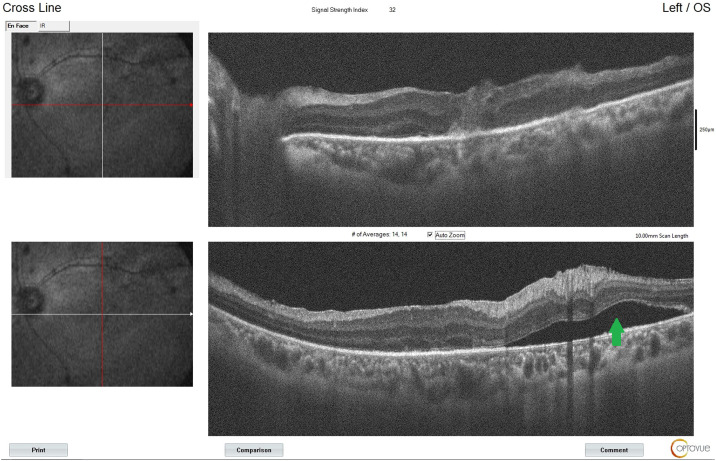

Figure 3.

Optomap wide-angle fundus image taken on the postoperative 20th day.

Figure 4.

Optical coherence tomography angiography image taken on the 20th postoperative day showing choroidal neovascularization (blue star) and subretinal fluid (green arrow) in the lesion area.

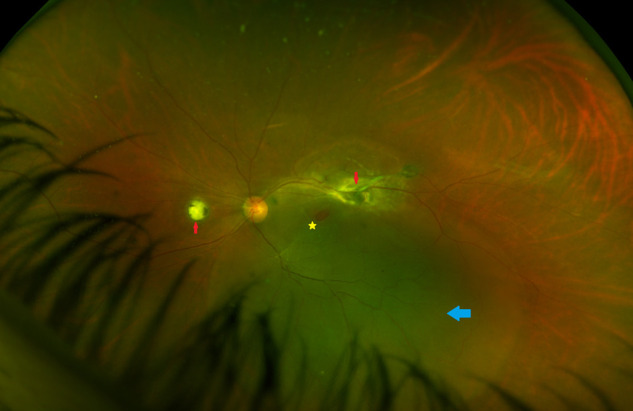

In the second-month follow-up, retinal attachment and macular hole closure were observed again. The patient's best corrected visual acuity increased to 20/100 (Figure 5, Figure 6 ).

Figure 5.

Optomap wide-angle fundus image taken at the postoperative second month.

Figure 6.

Optical coherence tomography angiography image taken at the postoperative second month showing that the macular hole is closed, and the retina is attached. There is subretinal fluid (green arrow) around the area of chorioretinitis.

Discussion

Toxoplasma chorioretinitis is a self-limiting infection in immunocompromised individuals. Many patients without the involvement of posterior segment structures or development of severe intraocular inflammation can improve without treatment. However, the disease may progress very aggressively in immunosuppressed individuals [5]. In particular, the cellular immune system plays a major role in the body in protecting against T. gondii infections [6]. Although our patient did not have a known immunosuppressive condition, her anamnesis showed that she had recently contracted COVID-19 and recovered with treatment. There are not yet any reports describing an increase in T. gondii infections in patients with COVID-19. However, it is considered that the decrease in the functions of cellular immune system cells in individuals that have suffered from COVID-19 may pave the way for opportunistic infections [7]. This suggests that our case having had a COVID-19 infection approximately two weeks earlier may have caused reactivation in ocular toxoplasmosis. At the same time, systemic steroids used in the treatment process of COVID-19 may also play a role in the exacerbation of this condition [5]. However, there is a need for further research to clarify this issue.

In a 1990 animal study, Robbins et al. reported that a coronavirus-related disease, which could progress acutely and chronically, could be induced in the retina. They described this disease model as experimental coronavirus retinopathy. One of the key points reported in a similar study by the same team was that the coronavirus led to the development of retinal tropism through several different pathways. Another interesting point mentioned in their studies was that infection could accelerate the fibrosis and retinal atrophy processes by triggering fibroblast activity in retinal tissues, such as the retinal pigment epithelium [8], [9], [10]. Thus, we consider that in our case, the atypical tractional forces caused by toxoplasma chorioretinitis after COVID-19 may have led to the development of both a macular hole and retinal detachment through this triggered fibrosis process.

In ocular toxoplasmosis, prognosis is good provided that there is no involvement of the macula or optic nerve head. Rarely, complications requiring vitreoretinal surgical interventions, such as rhegmatogenous or tractional retinal detachment, epiretinal membrane, macular holes, and vitreous hemorrhage may be seen [11]. The literature contains a limited number of publications on the surgical treatment and results of macular holes or retinal detachment secondary to ocular toxoplasmosis. However, to our current knowledge, our case report is the first in the literature to publish the results of vitreoretinal surgery in which a macular hole and retinal detachment secondary to ocular toxoplasmosis were seen together.

Macular hole is a defect that occurs in the fovea and involves all retinal layers [12]. The prevalence of a macular hole secondary to ocular toxoplasmosis is very low, and a gold standard treatment has not yet been established. The mechanism of full-thickness macular hole formation secondary to toxoplasma chorioretinitis remains unclear. However, tractional forces caused by intraocular inflammation, atrophy around the lesion, and vitreomacular traction due to this atrophy are implicated in its pathogenesis [13], [14]. In the literature, there are four articles reporting the surgical results of a macular hole secondary to toxoplasma chorioretinitis. In these publications, a total of 14 cases were described, and macular holes were anatomically closed in all cases after surgery. Similarly, an increase in postoperative visual acuity was reported in all of these 14 cases [14], [15], [16], [17]. In one of these case reports, Ikeda et al. described the use of the inverted ILM flap technique in addition to PPV and ILM peeling as a surgical method. In the remaining 13 cases, standard macular hole surgery was performed. We also used the inverted ILM flap technique in our case and achieved anatomical success. It is suggested that the ILM placed in the macular hole with this technique acts as a bridge for degenerated retinal cells and contributes to the closure of the hole [14], [18]. One of the previously published 14 cases did not have successful closure of the macular hole with the first surgery, and thus second surgery was required [15].

Tractional forces due to intraocular inflammation and atrophic retinal areas are responsible for the pathogenesis of retinal detachment, which is a rare complication that may develop secondary to toxoplasma chorioretinitis. There are various publications in the literature concerning the surgical correction of this complication, which can seriously threaten vision. scleral buckling or PPV with the use of silicone oil or endotamponade gas can be preferred as the surgical method. In our case, we preferred PPV with ILM peeling and gas endotamponade with SF6 since retinal detachment was accompanied by a macular hole. Postoperative results may vary depending on the condition of the macula, time between the development of detachment and surgery, and presence of proliferative vitreoretinopathy [19], [20]. According to the results of our second-month postoperative examination, our patients achieved anatomical and functional improvement. We consider that this study is important because it reports the first case in which a macular hole and retinal detachment secondary to ocular toxoplasmosis were seen together and describes the treatment process with medical and vitreoretinal surgery.

In various publications, the probability of developing CNV in areas of old chorioretinal atrophy due to toxoplasma has been reported as 2–19%. However, CNV accompanying an already active toxoplasma lesion is a very rare condition. Cracks in Bruch's membrane and the choriocapillaris layer as a result of chorioretinitis are held responsible for the development of subretinal CNV. In addition to antibiotherapy for toxoplasma, intravitreal anti-VEGF injection is an important alternative used in treatment [21], [22]. In our patient, OCTA imaging revealed subretinal CNV in the active and old chorioretinitis areas in the superior temporal arcuate region. We administered a single dose of intravitreal anti-VEGF to the patient approximately three weeks after vitreoretinal surgery and determined that the size of CNV was decreased in the follow-up. However, we observed some subretinal fluid around the lesion even at two months after successful vitreoretinal surgery (Fig. 6).

Macular holes are responsible for approximately 1% of all rhegmatogenous retinal detachment cases [23], [24], and the pathological myopia group constitutes the majority of these cases. Vitreomacular traction and tangential forces are effective in the mechanism of macular holes leading to retinal detachment [24]. In our case, as mentioned above, tractional forces leading to the development of retinal detachment may have been associated with intraocular inflammation, chorioretinal atrophy, and macular holes. Another factor that may have played a role in the development of retinal detachment is CNV-related subretinal fluid. We consider that subretinal fluid accumulating in the superior temporal macula region due to CNV may have moved to the fovea center over time, triggering or accelerating the development of retinal detachment. Therefore, the reduction of the size of CNV and subretinal fluid with intravitreal anti-VEGF and successful vitreoretinal surgery are important in achieving anatomical and functional success.

In conclusion, we consider that this ocular toxoplasmosis case complicated by a macular hole, retinal detachment, and CNV will contribute to the literature in terms of both its surgical and medical management and relationship with COVID-19. We look forward to further studies on this subject.

Funding

No specific financial was available for this study.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Jabs D.A., Nguyen Q.D. In: Ryan S.J., editor. Mosby; St.Louis: 2001. Ocular toxoplasmosis; pp. p.1531–p.1544. (Retina). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss M.J., Velazqez N., Hofeldt A.J. Serologic tests in the diagnosis of presumed toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109:407–411. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74606-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland G.N. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Part II: disease manifestations and management. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothova A. Ocular manifestations of toxoplasmosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003;14:384–388. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200312000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merih Oray, Pinar Cakar Ozdal, Zafer Cebeci, Nur Kir, Ilknur, Tugal-Tutkun Fulminant ocular toxoplasmosis: the hazards of corticosteroid monotherapy. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2016;24:637–646. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2015.1057599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatoohi A.F., Cozon G.J.N., Gonzalo P., Mayencon M., Greenland T., Picot S., et al. Heterogeneity in cellular and humoral immune responses against Toxoplasma gondii antigen in humans. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 2004;136:535–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng H.Y., Zhang M., Yang C.X., Zhang N., Wang X.C., Yang X.P., et al. Elevated exhaustion levels and reduced functional diversity of T cells in peripheral blood may predict severe progression in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:541–543. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0401-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robbins S.G., Detrick B., Hooks J.J. Retinopathy following intravitreal injection of mice with MHV strain JHM. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1990;276:519–524. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5823-7_72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robbins S.G., Detrick B., Hooks J.J. Ocular tropisms of murine coronavirus (strain JHM) after inoculation by various routes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:1883–1893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neri P., Pichi F. COVID-19 and the eye immunity: lesson learned from the past and possible new therapeutic insights. Int Ophthalmol. 2020;40:1057–1060. doi: 10.1007/s10792-020-01389-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delair E., Latkany P., Noble A.G., Rabiah P., McLeod R., Brézin A. Clinical manifestations of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2011;19:91–102. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2011.564068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gedik B., Suren E., Bulut M., Durmaz D., Erol M.K. Changes in choroidal blood flow in patients with macular hole after surgery. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2021;35:102428. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aleixo A.L., Curi A.L., Benchimol E.I., Amendoeira M.R. Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis: clinical characteristics and visual outcome in a prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeda M., Baba T., Aikawa Y., Yotsukura J., Yokouchi H., Yamamoto S: Case of macular hole secondary to ocular toxoplasmosis treated successfully by vitrectomy with inverted internal limiting membrane flap. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2021;12:363–368. doi: 10.1159/000514910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arana B., Fonollosa A., Artaraz J., Martinez-Berriotxoa A., Martinez-Alday N. Macular hole secondary to toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34:141–143. doi: 10.1007/s10792-013-9754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sousa D.C., Andrade G.C., Nascimento H., Maia A., Muccioli C. Macular hole associated with toxoplasmosis: a surgical case series. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021 Mar 1;15:110–113. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka R., Obata R., Sawamura H., et al. Temporal changes in a giant macular hole formed secondary to toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49:e115–e118. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozdogan Y.C., Erol M.K., Suren E., Gedik B. Internal limiting membrane graft in full-thickness macular hole secondary to macular telangiectasia type 2. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2021;29 doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreira F.V., Iwanusk A.M., Amaral A.R.D., Nobrega M.J., Novelli F.J. Surgical outcomes of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment associated with ocular toxoplasmosis. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2018;81:281–285. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20180057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faridi A., Yeh S., Suhler E.B., Smith J.R., Flaxel C.J. Retinal detachment associated with ocular toxoplasmosis. Retina. 2015;35:358–363. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart L., Fine, Sarah L., Owens, Julia A., Haller, et al. Choroidal neovascularization as a late complication of ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;91:318–322. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(81)90283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegde S., Relhan N., Pathengay A., Bawdekar A., Choudhury H., Jindal A., et al. Coexisting choroidal neovascularization and active retinochoroiditis-an uncommon presentation of ocular toxoplasmosis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2015;5:22. doi: 10.1186/s12348-015-0051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daniel A., Brinton C.P., Wilkinson . 2009. Retınal detachment principles and practice Third Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morita H., Ideta H., Ito K., et al. Causative factors of retinal detachment in macular holes. Retina. 1991;11:281–284. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199111030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]