Abstract

This systematic review emphasizes the need for technology use in older adults to reduce social isolation. With the advancement of technology over the years, the effectiveness of interventions based on its use can be examined to see how these can address the problem of social isolation and enhance social wellbeing. We focus on identifying how older adults can most benefit from affordable and accessible technology use and how the training and implementation of such interventions can be tailored to maximize their beneficial effect. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to select relevant studies. We analyzed 25 articles, performed a narrative analysis to identify themes, and quality of life indicators connected to technology use and wellbeing. Engagement of older adults at the community-level, following best practices from the Community-Based Participatory Research can facilitate effective practices to deliver technology based social isolation interventions and increase digital use self-efficacy in older adults. Mobile technology-based applications not only help families to stay connected, but also link older adults to resources in healthcare and encourage physical and mental well-being. Use of technology devices address cognitive, visual, and hearing needs, and increase digital use self-efficacy in older adults, particularly helpful during necessary social distancing or self-quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Social isolation, Older adults, Quality of life, Digital use efficacy

Highlights

-

•

Digital use efficacy in older adults can reduce social isolation.

-

•

An integrated community-based approach with rolling-wave planning to support isolated seniors.

-

•

Absence of measurable definitions adds to difficulty in developing measurable interventions in research.

-

•

Implementation of technology intervention can be tailored to maximize beneficial effect.

-

•

Use of both online and offline resources to improve accuracy and efficiency of interventions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Social isolation, (SI) is one of the most disruptive transformations facing the aging population in the recent history (Datta, Bhatia, Noll, & Dixit, 2019). It implies the absence of human contact or meaningful social relations that adversely impacts the quality of life of older adults, significantly deteriorating their emotional and physical health (Ahn and Shin, 2013). For older adults, social wellbeing involves certain external and internal criteria such as an observable presence of connections or exchanges, as well as satisfaction with their quality (Sen and Prybutok, 2020; Hudson & Doogan, 2019). Technology based communication may foster social wellbeing when every older adult is able to participate successfully in today's digital society through devices that provide free access to information and interaction with others, offer appropriate security for health services, and feature easy-to-use authentication and interaction mechanisms (Datta et al., 2019), increasingly more prevalent in the United States. Hence, technology may offer alternative means for ameliorating SI in older adults, and partly offset the negative impact on health (Dennis, Alamanos, Papagiannidis, & Bourlakis, 2016). Appropriate amounts of social interaction is critical to successful aging (Feng, Cramm, Jin, Twisk, & Nieboer, 2020).

This systematic review examines the use of digital technology and its impact on social wellbeing of older adults mostly above 65 years. We emphasized on the understanding of social perspectives related to SI. While research had investigated use of digital technology in the form of audio and video communication for social interaction, no review has looked into the wellbeing outcomes of older adults with respect to technology use.

In geriatric health research, preventing SI is an overarching issue (Kruse et all., 2020), especially with the surge of seniors living alone. Cudjoe et al. (2020) found, that 7.7 million older adults in the U.S. are socially isolated and 1.3 million are at the threshold of the effects of SI, which account for those who are severely socially isolated. The older adult population is estimated to reach 70 million or to increase by approximately 20% by 2030, which indicates that many seniors will be living alone and will be at risk for SI (Johnson, Bulot, & Johnson, 2008). With the advancement of age, there is a decline in social engagement, owing to life situations emerging from ailments, living arrangements, changes in marital status, impaired mobility, death or separation from family, that negatively affects emotional stability and overall quality of life for seniors. For the oldest old, the reciprocity of relationships, social activity participation, mealtime enjoyment, and the perceived friendliness of formal and informal caregivers are extremely limited (Park, 2009).

Technology helps to overcome the social and spatial barriers of social interaction for the elderly by enabling easily accessible and affordable communication devices that foster interaction in multiple forms like text messaging, email, and audio or video communication anytime and anywhere. Many older adults are connected by digital media in contemporary society, but their networks are significantly limited (Sprecher, Hampton, Heinzel, & Felmlee, 2016). Not all older adults are skilled at using digital media to keep in touch with traditional family groups and neighbors and are less adept at leveraging the advantages of technology to connect more effectively. Moreover, with low level of health literacy, the potential to improve social participation diminishes (Amoah, 2018) and in most cases, older adults are not able to overcome the barriers of time and space to discover new life experiences factoring from the lack of training or economic constraints to internet accessibility.

In the post COVID world, virtual reality has replaced face-to-face communication in humans with significant impacts on social connectivity (Mitzner, Stuck, Hartley, Beer, & Rogers, 2017). For example, seniors can interact with each other within a three-dimensional environment with access to virtual field trips like a museum visit with their old friends. Various forms of easily affordable and accessible technologies provide a safe environment for seniors to be informed about healthcare, and to engage in social interaction while remaining in a safe environment. For instance, watching television alone might foster new health related information, but reduce the level of social engagement, while emails, video calling, or text messaging might foster it by removing distance between adults. Long-distance communication through e-mail or phone is particularly helpful in sustaining relationships among older adults. For example, many older adults living geographically distant from their grandchildren have extensive phone and e-mail communication, with high levels of emotional satisfaction, compared with individuals communicating in-person only (Holladay & Seipke, 2007). However, some older adults perceive e-mail communication to be lacking the personal touch that they experience using phone calls or letters (Dickinson & Hill, 2007; Lindley, Harper, & Sellen, 2009).

1.2. Purpose

The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the extent to which technology can be used to address the problem of SI and enhance the quality of life for older adults. While several recent reviews have explored technological interventions designed to address SI, a unique aspect of this systematic review is to determine how the elderly population can most benefit from technology use in reducing SI. These insights will benefit all those exploring the ways in which technology can contribute to the well-being of older adults.

2. Methodology

2.1. Protocol

This systematic literature review incorporates small design articles and prototype evaluations from the field of human-computer interaction that help us to consider the latest techniques and technologies being applied in the field. The search of the literature was undertaken utilizing PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Page et al., 2021a, 2021b). The PRISMA 27-item checklist was used tactically to build the review process. We used the PRISMA three-phase flow diagram to narrow down our search to exactly what we wanted to review from the existing peer reviewed literature.

2.2. Information sources

Our literature search included various electronic databases: Science Direct, Scopus, CINAHL, PubMed, Ebscohost, Proquest, Research Library, Ingenta Connect, MEDLINE and Springer Link, using key words combined with the Boolean operators (AND, OR). For example, the key words for Information and Communication Technology (computer, cell phone, tablet, eHealth, iPad) were combined with terms relating to older adults (seniors, baby boomers, elderly, aging population) and terms for frameworks (model, framework, indicator, definition, measure). All the terms were searched in abstracts, key words, subject headings, titles, and texts. In addition to the database search, a specific journal search was conducted in the journal of choice for publication (SSM Population Health) and the online archives of specific journals that publish research on various aging issues including ‘Social Indicators Research’ and ‘Computers in Human Behavior’ using ‘technology’ and ‘older adults’ as the key search terms. Databases were filtered for the last 12 years, as it has been long since the last review was published on a similar topic.

2.3. Search

We searched the MEDLINE, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for key terms related to technology and elderly people. Based on the established hierarchy of indexed terms at MeSH and a series of experimental searches, the final search terms were ‘technology’, ‘social isolation’ and ‘older adults.’ This combination of terms yielded the maximum number of results in all the selected databases. We used available filters to eliminate other reviews and focus on academic or peer-reviewed journals over the last 12 years.

2.4. Eligibility criteria

All articles in this review were peer-reviewed between the years 2009 to year 2021. Inclusion criteria, including the three key search terms, are as identified in Table 1.1. Technology as is referred, includes technology devices like the computer, cell phone, tablet, iPad, or any form of software, weblink, or website. The sample characteristics include older adults above 65 years of age who are retired and mostly living alone, male or female, irrespective of race, ethnicity, or marital status. The key search words included: SI, social inclusion, social engagement, technology, and older adults.

Table 1.1.

Search strategy boolean operators and modifiers.

| Key Search Terms – Technology (Boolean Operators OR, AND) | Key search terms – Older Adult (Boolean Operator OR, AND) | Key search word – Social isolation/social participation |

|---|---|---|

| Information and Communication Technology | Older adults | Social |

| OR Elderly population | ||

| OR Technology | OR Aging population | |

| AND Computer, tablet, cell phone, iPad | AND Baby Boomers |

Search exclusion items are described in Table 1.2. We identified the search exclusion items while reviewing the initial search results. As this review focuses on empirical research, we excluded clinical trials, case references, editorials, commentaries, theoretical and descriptive articles. Articles on telemedicine, young adults, radiology, or imaging in technology were also excluded.

Table 1.2.

Excluded search terms.

| Excluded Search Terms (Boolean Operator AND NOT) |

|---|

| Radiology and Imaging OR |

| Medical Information Systems OR |

| Youth OR |

| Telemedicine OR |

| Young Adults OR |

| Robot OR |

| Geographic Information System OR |

| Information Management |

2.5. Study selection

Analysis of results involved a three-step process. Many articles emerged at step one from various search engines and weblinks as mentioned above. First, article titles and abstracts were screened for search terms and exclusions. Duplicates were removed automatically and then manually. Second, articles were screened by title and abstract independently to identify those that broadly met the inclusion criteria. Articles were assessed by reading the full text. Third, full-text articles were retrieved, and data extraction was undertaken using a modified template from PRISMA. For each study, data extraction and collation included (i) the type of technology being used; (ii) the study aims; (iii) method used; (iv) social concepts; (v) summary of outcomes.

2.6. Data collection and synthesis

Articles were not restricted by study design or outcome measures. Both qualitative and quantitative research articles were included. We focused on the range of outcome measures and not on the report of statistical data. Primary outcomes from the study relate to the use of technologies and the perceptions of older adults towards it, which in turn increases the possibility of social participation to reduce SI. The articles were summarized by objective in the results section, and by grouping them by the key outcomes. Secondary outcomes relate to subsequent improvement in use of various modes of technology that enhances the accessibility of their use in older adults.

2.7. The quality of included articles

As per our objective, the articles that described the frameworks of technology were not appraised, as these were descriptive reports. As per our second objective, we included articles reporting empirical research that had simple criteria based on published checklists (Crombie, 1996). We assessed articles based on the description of the study (technology used, study aims, social concepts, outcomes). For qualitative references, we included the indicators about appropriateness and reliability of analysis. For quantitative data, we assessed whether the basic data was described, and whether statistical significance was assessed. All articles provided adequate descriptions regarding study purpose, sample or participants, methodology and measures. Ten articles used qualitative methods (semi structured interviews, focus group discussions). Ten articles used quantitative methods, one study used a mixed-methods research, and four articles were based on survey research methods (Table 1.5). Nine articles provided detailed information on how study participants were selected. All ten articles based on quantitative research provided information on methods of data analysis. Of the ten articles that used qualitative methods, five articles used quoted words and phrases from research participants for reporting (References 5,6,10, 17, 20). References that provided statistical analyses reported a rationale for statistical calculations.

Table 1.5.

Study types included in the review.

| Study types | Number of papers | Reference | Author and Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview-based qualitative evaluation | 10 | 1 | Judges et al. (2017) |

| 2 | Wang et al. (2018) | ||

| 5 | Czaja et al. (2018) | ||

| 6 | Kadylak et al. (2018) | ||

| 10 | Chen et al., 2016 | ||

| 12 | Coleman, Gibson, Hanson, Bobrowicz,& McKay (2010) | ||

| 17 | Roberts et al. (2019) | ||

| 18 | Hill, Betts, & Gardner, 2015 | ||

| 2 | Baecker et al. (2014) | ||

| 22 | Karanasios, Cooper, Adrot, & Mercieca (2020) | ||

| Surveys of older adults' use of technology | 4 | 11 14 16 23 |

Dennis et al., 2016,Sum et al., 2009 Lelkes (2013) Hunsaker, Hargittai, & Piper (2020) |

| Mixed-method evaluation | 1 | 25 | Fields et al., 2020 |

| Quantitative evaluation | 10 | 3 | Ihm and Hsieh (2015) |

| 4 | Czaja et al. (2018) | ||

| 7 | Vošner, Bobek, Kokol & Krečič (2016) | ||

| 8 | Vroman et al. (2015) | ||

| 9 | Chai and Kalyal (2019) | ||

| 13 | Pierewan, & Tampubolon, 2014 | ||

| 15 | Heo et al., 2011 | ||

| 19 | Kearns and Whitley (2019) | ||

| 21 | Jaana & Pare (2020) | ||

| 24 | Talmage et al. (2020) |

3. Results

The initial search of information sources at step one yielded an initial scan of 263 articles from the databases, with the breakdown of results from each database presented in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3.

Results from initial search of included databases.

| Electronic Research Database | Results |

|---|---|

| Scopus | 31 |

| CINAHL | 26 |

| Science Direct | 37 |

| Ingenta Connect | 32 |

| Ebscohost | 25 |

| Proquest | 26 |

| MEDLINE | 24 |

| Springer Link | 28 |

| Research Library | 24 |

| PubMed | 10 |

| Total | 263 |

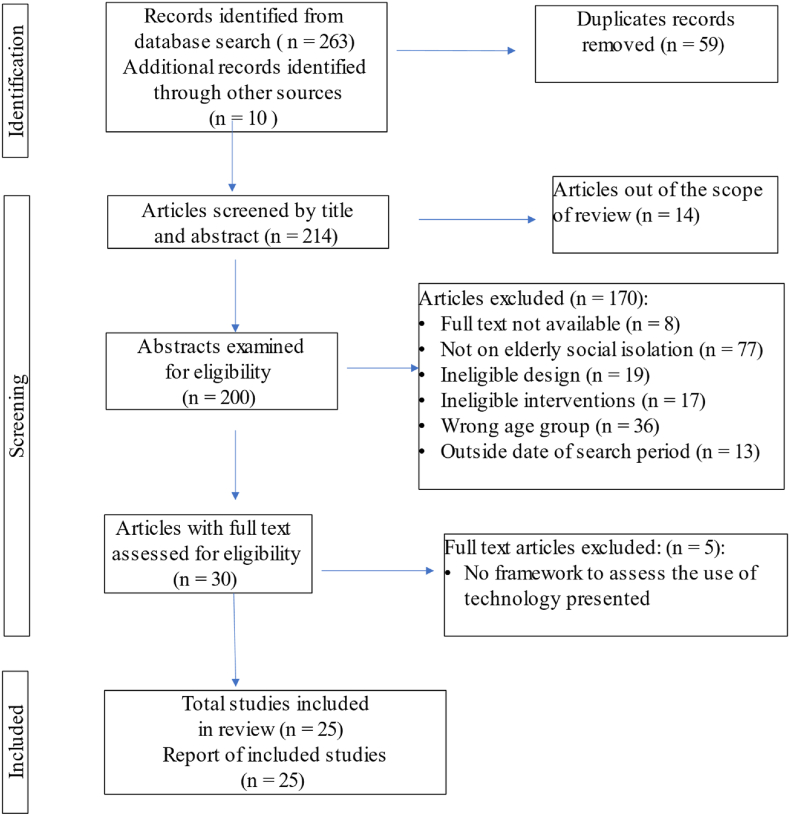

Fig. 1.1 shows results from the four-step process. First, we identified 273 records, of which 263 records were from the database search and 10 records were from journals identified, namely, ‘SSM Population Health’, ‘Social Indicators Research’, and ‘Computers in Human Behavior’ using ‘technology’ and ‘older adults’ as the key search terms. At step two, 59 duplicate articles were eliminated, and abstracts were manually reviewed and evaluated according to inclusion criteria. The result was 214 remaining articles. Out of these, 14 articles were out of the scope of review. At step three, 200 articles were reviewed. Of these, 170 were excluded on the following grounds: (i) some articles did not satisfy all the inclusion criteria and deviated from the topic; (ii) some articles only focused on the use of technology without demonstrating how it could reduce social barriers in the elderly; (iii) some articles did not match the age group of older adults above 65 years; (iv) some lacked methodological detail; (v) some articles lacked proper analysis of statistical data; (vi) some did not include the description of interventions used; (vii) some articles were just descriptive or theoretical References and not based on empirical research; (viii) some articles were outside the date range of search. This reduced the numbers resulting at 30. Out of these, 5 articles did not have any framework for assessment of the use of technology among older adults. Hence, at the last step or step four, the final 25 articles were considered for review using the PRISMA template.

Fig. 1.1.

Flow diagram of study selection procedure and results.

(This figure is adapted from Page et al., 2021a, 2021b).

3.1. Selection process for systematic review

Table 1.4 provides a summary of the main aspects of the 25 papers included in the review. The findings are combined in terms of common themes. The articles are identified by references written in APA 6th edition format. The table contains reports on the type of technology used, the aims, the social concepts discussed in each paper and the key outcome measures. In Table 1.5, the methods utilized by each study are described.

Table 1.4.

Summary of results.

| Author and Year | Aim | Social concepts | Key outcomes | Study types | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital communication tool ‘called In touch' | Judges, Laanemets, Stern, and Baecker (2017) | Patterns of use of ‘InTouch’ by older adults over 3-months, relationships between demographic, health and social profiles and adoption of ‘InTouch’, effect ‘InTouch’ may have on socioemotional well-being | Motivation, social difficulties, health issues, experience with learning | Positive communication changes, positive relationship changes, technology is easy to use with one-on-one support. | Interview-based qualitative evaluation |

| Networked individuals exhibit certain network older adults network attributes, such as network diversity and relational autonomy | Wang, Zhang, and Wellman (2018) | In depth and face to face interviews with older adults to find out whether they are really networked individuals and how much they rely on social networks | Older adults were socially connected, their networks were limited, hence they were not networked individuals | Digital media expanded geographical reach of older adults' social networks,facilitated communication with peers and younger generations, helped organize social and group events, promoted diversity, and augmented exchange of social support | Interview-based qualitative evaluation |

| Technology benefits have crucial implications for users' socio-economic mobility as well as their social wellbeing. | Ihm and Hsieh (2015) | Older adults' uses of technology and disparities in use | New theoretical insight in the implications of digital inequality for the seemingly related concepts of online and offline social activities. | The essence of technology access and use lies in the well-being of the users and their abilities to deploy technology rather than in mere access to it | Quantitative evaluation |

| Evaluated the impact of a specially designed computer system for older adults | Czaja, Boot, Charness, Rogers, and Sharit (2018) | Access to PRISM to enhance social connectivity and reduce loneliness among older adults, change attitudes toward technology and increase technology self-efficacy. | Computer proficiency, reduced social connections and attitudes toward technology use to connect to others | An increase in computer self efficacy, proficiency, and comfort with computers for PRISM participants at 6 and 12 months. | Quantitative evaluation |

| Communication preferences and patterns of use of technology with emphasis on technologically-mediated environments. | Yuan, Hussain, Hales, & Cotten, 2016 | Examine older adults' communication patterns and preferences with family members and friends, as well as their views about the impacts of modern technology on communication | Three themes: communication preferences and reasons, communication barriers, the impacts of technology | Face-to-face communication is the most preferred method, telephone communication is the most adopted method. Interviewees also shared different opinions regarding Internet-based communication. | Interview-based qualitative evaluation |

| Mobile phone use during face-to-face interactions | Kadylak et al. (2018) | Older adults' perceptions of mobile phone use during face-to-face interactions and social gatherings | Mobile phone behavior displayed by younger family members during face-to-face interactions and family gatherings breaches expectations | Older adults view mobile phone etiquette of younger people as offensive and disruptive, potentially exacerbating intergenerational divides |

Interview-based qualitative evaluation |

| Online social network use by older adults | Vošner, Bobek, Kokol & Krečič (2016) | Factors affecting the use of online social networks by active older Internet users | How often, and to what extent, active older Internet users are engaged with the society in using technology and how they connect with others. | Female participants are more familiar with ‘online social network’ and more frequent users, compared to males. Age, gender and education seem to be the most important factors having a direct or indirect impact on the use of online social networks. | Quantitative evaluation |

| Patterns of information communication technology use | Vroman, Arthanat, and Lysack (2015) | Technology experiences, and socio-personal characteristics of older adults and analysis of dispositional correlates of technology adoption. | Participants used technology to maintain family and social connections and to access information on health and routine activities. | The older population's age, education, attitudes, and personalities influence how they approach technology | Quantitative evaluation |

| Information communication technology use | Chai and Kalyal (2019) | Explores the relationship between cell phone use and self-reported happiness among older adults | Happiness of Chinese older adults is affected by a growing shift in traditional family values due to the unprecedented economic growth. | Using own cell phone is positively associated with self-reported happiness among Chinese older adults | Quantitative evaluation |

| IT and the older adult quality of life | Chen, Downey, McGaughey, and Jin (2016) | Attitudes and behaviors as they relate to the use of technology | Insight into quantity and diversity of senior technology use in urban China, potential factors that motivate or hinder senior's use of information, comfort with technology, and positive and negative attitudes. | Majority of respondents have been exposed to IT and participated in its use. Cell phone use far exceeded computer use. | Interview-based qualitative evaluation |

| Cell phone and computer for online shopping by older adults and reduce social isolation | Dennis et al. (2016) | Social exclusion affects consumer use of multiple shopping channels and how these choices affect consumers' happiness and wellbeing. | Cellphones are important for socially excluded people. Supports their shopping activities and improves happiness and well-being. | Shopping by cell phone significantly ameliorates the negative effects of social exclusion on happiness and wellbeing for consumers with mobility/disability issues. | Surveys of older adults' use of technology |

| Technology acceptance in older adults | Coleman, Gibson, Hanson, Bobrowicz,& McKay (2010) | Issues of technology non-acceptance amongst older adults | Current technology use by the informants while keeping in mind possible technology solutions, by identifying activities they would like to do | Work designed to incorporate the values of older adults within the technology design process. | Interview-based qualitative evaluation |

| Internet use and wellbeing of older adults | Pierewan, & Tampubolon, 2014 | Association between Internet use and well-being before and during the financial crisis in Europe which started in 2007. | Internet use increases the wellbeing through communication with family during the economic crisis | Internet use explains well-being differently at different times due to financial constraints at a time of crisis, people tend to substitute offline companionship with online social interaction. | Quantitative evaluation |

| Internet use and wellbeing of older adults | Sum, Mathews, Pourghasem, and Hughes (2009) | Internet use and seniors' sense of community and well-being | Internet use associated with higher satisfaction with health, contact with family and friends, involvement with hobbies or interests, and overall happiness | Seniors' use of the Internet for communication and information, and the frequency and history of their Internet use, is related to a greater sense of community. | Surveys of older adults' use of technology |

| Internet use and satisfaction of older adults | Heo, Kim, & Won, 2011 | How the Internet is related to leisure satisfaction | The relationship between older adults' leisure satisfaction and their affinity for the Internet. | Those who are likely to acknowledge the importance of the Internet tend to be satisfied with using it as a leisure activity. | Quantitative evaluation |

| Regular internet use and self-reported life satisfaction | Lelkes (2013) | Does internet use make older people less or more lonely? Does it crowd out face-to-face contacts or enhance them | Personal social meetings and virtual contacts are complimentary to each other for older adults | People still want to see each other personally if they have interaction via the internet. Internet use is associated with lower social isolation among those aged 65 or over | Surveys of older adults' use of technology |

| Older adults respond to audiovisual virtual reality | Roberts, De Schutter, Franks, and Radina (2019) | How older adults living in a continuing care retirement community (CCRC) respond to audiovisual communication and virtual reality | Maximizing positive aspects of virtual reality through increasing interactivity, facilitating socializing with friends or family, and enhancing older adults' ease of use. | Virtual reality was reviewed positively, yet modifications are necessary to facilitate optimal user experience and potential benefit for this population. | Interview-based qualitative evaluation |

| Experiential account of older adults' use of, and attitudes towards, digital technology and the impact of digital technology use on their wellbeing. | Hill, Betts, & Gardner (2015) | How older adults use digital technology, impact of digital technology on older adults' wellbeing, attitudes towards digital technology | Digital technology as a tool to disempower and empower older adults. Clusters of talk expressing barriers, negative consequences, and debilitating impacts of technology on individuals and their perception of the wider community and empowering aspects of digital technology. | Value of technology as an empowering entity that could facilitate daily activities and maintain social relationships whilst successfully overcoming physical and geographical barriers. Also disempower and without appropriate skills or measures tackle fear associated with technology use. | Interview-based qualitative evaluation |

| Wellbeing effects of internet use among older adults in deprived communities | Kearns and Whitley (2019) | Potential effects of internet access in older adults of deprived communities, distinguish between internet access via mobile phone or home computer | Use of the internet and frequency of access at home, via a mobile phone, in a public venue, or other means. | Inequalities in internet access within deprived communities, use of internet lowest among older people, those with a long-standing illness, and those with no educational qualifications | Quantitative evaluation |

| How technology facilitates social connection | Baecker, Sellen, Crosskey, Boscart, and Barbosa Neves (2014) | Integrating the existing common forms of communication, such as email and use of a smartphone by family member to a communicate with a senior | Technology use for social connections for the seniors in retirement communities and in long-term care settings like nursing homes. | Elicits communication needs and patterns of people in environments often associated with social isolation, and the role that technology plays in facilitating social connection | Qualitative evaluation, Smaller scale design, pilot and/or prototype evaluations |

| Use of mHealth in seniors | Jaana & Pare (2020) | Use of mHealth technologies in older adults and general population and explores the factors related to their use. | Seniors' attitudes toward and use of mHealth technologies for self-tracking purposes, factors that influence the continued usage of mHealth technologies | High satisfaction rate with mHealth and favorable conditions for their use. Many have already acquired these technologies, presents an opportunity to leverage them, beyond basic communication use, to support their wellbeing | Quantitative evaluation |

| Seniors' use of technology in critical settings | Karanasios, Cooper, Adrot, & Mercieca (2020) | Seniors use of technology mediated information behavior during disasters in a state of Australia and the challenges seniors face in accessing relevant information and using TECHNOLOGY. | Seniors embody and tap into local knowledge, mingle offline and take online cues about emergency situations, and maintain trust towards institutions. | Seniors are not simply passive victims and highlighting their appetite for precise and reliable information. When faced with incomplete or absent official information they can draw on technology to share information, connect and fill information needs | Interview-based qualitative evaluation |

| Socializing online and general anxiety among older adults | Hunsaker, Hargittai, & Piper (2020) | Examine the relationship between varying ways of socializing online and general anxiety. | There is a need to consider the ways that varying kinds of online social interactions relate to mental health and the unique relationships | Relationship between differing ways of socializing online and symptoms of anxiety, while controlling for socio-demographics, social context, Internet experiences, Internet skills, and health. | Surveys of older adults' use of technology |

| Benefits of advanced technologies | Talmage et al. (2020) | Examine the connections between use of technology and older adult well-being | Loneliness cannot be broadly mitigated by providing access to car and driver services. Practitioners should introduce seniors to ride-sharing services | Older adults may be more skilled at using tablets/computers to access the internet as opposed to cellphones, based on smartphone utilization estimates | Quantitative evaluation |

| Digital training to older adults. | Fields et al.,. 2020 | Evaluate impact of technology training on older adults' loneliness, social support, and technology use in real-world settings and assess barriers and facilitators to technology training implementation | Participant's personality match with their instructor for technology was central to their program experience | Digital literacy among participants was low overall, but participants' feelings of connection related to improving technology skills and digital literacy | Mixed-method evaluation |

Findings are classified into three key themes: (i) the digital technology used and its wellbeing effect on older adults (Table 1.4); (ii) the social concepts utilized in the papers to discuss outcomes (Table 1.4); and (iii) the methods incorporated in this body of empirical research (Table 1.5).

3.2. Digital technology use and its effect on senior wellbeing

Of the 25 articles reviewed, the largest segment focused on research into older adults' use of digital networks (References 1,3,6,7,8,9,11,13,15,21,22,24,25). Among these References, four were examinations of older adults’ satisfaction with the use of technology (References 14, 16, 15,21) and six examined technologies as they relate to changes in wellbeing (References 3,11, 13, 14,18,21) of older adults. Eleven (References 14,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25) articles evaluated the frequency and the history of Internet use by seniors. Two articles (References 3,24) examined the benefits of the use of technology. Six studies (References 3,4,8,19, 22, 24) investigated the accessibility of technology to older adults and one study (Reference 25) was based on technology training and the conditions for use based on the perceived needs of the users.

Most of the articles were skewed towards interfaces for older adults (References 1,24) and examined the patterns of use, participant profiles, and their adoption of technology. Much of the software incorporated social interaction features, such as photographs, videoconferences with family members and friends (References 1,5, 6,8, 9,14, 17, 20) The other articles were mostly evaluations of the impact of technology in providing support for older adults’ social participation. These References collected data through focus group interviews about experiences with technology or Internet usage for social inclusion.

3.3. Social concepts used to determine outcomes

The social concepts employed in the literature review were insufficient in 14 out of 25 reviewed articles. These studies did not provide clear or measurable definitions of social interaction or SI, which adds to difficulty in developing measurable interventions in research to address SI in the future. Again, phrases like ‘Internet use explains wellbeing’ (Reference 3) or ‘inequalities in Internet access’ (Reference 9), do not give us a clear idea of the concepts of social participation or of SI. Only 6 studies (References 2, 6,11, 13, 18,23) offered an explicit definition that was based on a uniform measure of social outcomes.

3.4. The scope of the methods included

SI and addressing it via the use of technology is the main theme of this review. The review intended to identify the impact of technology on participant's perceptions, motivation and accessibility to the use of technology to foster social interactions. This theme is based on pre-existing challenges that are related to the size of the participant's social network, complexity of social relationships, family dynamics, or their nature or interest in communicating with others. An overview of the range of study types included in the review is summarized in Table 1.5.

In the review, half of articles employed qualitative methods to evaluate the impact of technologies on social inclusion for older adults. These articles had small sample sizes (between 200 and 250 participants) and used a variety of qualitative methodologies such as ethnography, grounded theory, and action research. In Reference 20, we found a pilot or prototype evaluation that included an insightful analysis about novel uses of cutting-edge technologies. The rest of the qualitative papers have very small sample sizes below 200 (References 10, 12, 17 and 18).

4. Discussion

The findings from 25 articles add to the current body of knowledge on SI and the role of technology to combat it for the elderly. The key findings enable us to develop a critique of existing literature, discover limitations in the body of evidence, and make suggestions for further exploration.

First, the technologies included in the review showed the dominance of research focused on the impact of technology and on the existing unequal access to the Internet (References 5, 7, 9) by older adults. A measurement of the estimates of technology access by older adults will help in addressing the problem of isolation specially to meet the needs of the economically disadvantaged communities that remain unidentified. For example, the use of technology like mobile health has increased around the world due to COVID-19, but with that growth comes the possibility of a digital divide (Goto et al., 2021). Technology is expensive for those living on fixed incomes and are cash strapped to be able to afford to purchase or use new technologies. Besides cost, there are concerns in this population regarding the ability to utilize it efficiently, especially those with co-morbidities and disabilities of body physiology with exacerbating motor skills, eye, and hand coordination. Hence the issue is who among this population would be able to use technology with a clear understanding of what they need to be doing with the technological device or even how to interact with it. These are questions that needs to be resolved.

Social networking sites are just online tools for creating relationships with other people who share an interest, background, or real relationship (References 10, 17, 25). Hence, we suggest that future research focus on ways to expand Internet access for vulnerable seniors, and factors which can interfere with technology acceptance by a senior. A long-term approach that matches seniors with the technology intervention, that incorporates their interest with emphasis on needs and values of seniors in technology design can improve health outcomes. This population has relevant concerns with trust in technology, as they are often, prime targets for abuse through their use of technology. This fosters the need for technical support and training to develop technology use efficacy in seniors. The lack of affordable and adequate sources of “technical support” is a factor influencing technology literacy and its use. With a certain level of user knowledge, seniors would not only be able to connect to others socially, but also to utilize medical applications like telehealth or mHealth that is so vital to their health-related quality of life. While social networking is the most common foci for research in the literature included in the review, future research should measure the optimal user experience (References 1, 25) that might provoke additional research to design strategies towards senior technology access and user engagement.

Survey research (References 11, 14, 16, 23) based on the older adults in the U.S. suggests that social networks and their use increasingly influence the health-related quality of life for seniors (Reference 10). Hence, measuring the use of social media, like Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, and determining the knowledge of the personal and social characteristics of older adult technology users and nonusers, we can easily incorporate the values of older adults in the technology design process (Reference 8). Removal of barriers surrounding trust of the internet, problems of privacy and security or that of computer anxiety can enhance user knowledge and efficacy in its use. While we report an experiential account of older adults’ use of and attitudes towards digital technology, the current body of evidence suggests that we should focus on the use of more advanced technologies like instant messaging apps (Snapchat, or iMessage), participation in instantaneous polls and referenda, or the use of interactive media like Zoom and take advantage of possibilities that we cannot now imagine for augmenting technology skills in seniors (Reference 25). The emerging technology of virtual and augmented reality, its applications, or virtual assistants or even robots can either ameliorate or exacerbate the role of interpersonal processes in elder wellbeing (Reference 17). Hence, any future work suggested for a successful intervention, must include consistent measures or qualitative evidence of the success in each context. In this way we avoid investing resources in technologies for which there is inadequate evidence of effectiveness.

Second, we considered social concepts in this review. However, a standardized definition of SI or of social wellbeing is not uniformly evident in the body of literature reviewed. Different articles have addressed it in different ways. It is obvious that there exists a variety of assumptions about various social determinants impacting health outcomes (References 19, 20, 21,22). The concern is whether internet enabled devices can really connect and assist low-income, high health risk older adults living in local community centers or subsidized congregate housing provide for their health and social needs. We hope that a more standardized definition will help to successfully design an intervention with clearly definable outcomes. Authors have a variety of views about why the same type of technology intervention might impact social connectedness, but social contact is the most commonly conceptualized impacting factor across all intervention types. We hope that development of interventions to address social inclusion that target purposeful activity or engaging individuals should not be an anxiety generating experience (References 12 and 23) for older adults. For example, when, interventions are intertwined with intergenerational training programs to improve digital confidence, it can engage the older adults in an informal way and reduce anxiety of the training process. As the stakeholder priority and characteristics of participants vary to their needs and preferences (Reference 23) the mode of delivery of every intervention needs to be given attention in future research.

Third, methodologies incorporated into this review include both qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method research (Table 1.5) that targets social connectedness and seniors as preliminary users of technology. They rely mostly on preliminary user testing methods with less or almost no follow-up to see associated social or health benefits (Reference 18). Technology assessment as it relates to the activities of daily living (ADLs) can be useful for proper evaluation of older adult's wellbeing or self-reported happiness as individuals often respond differently depending on their background and circumstance. We could compare the effectiveness of each innovation to enhance the knowledge about ways to promote the design for effectiveness that promote both healthcare delivery and the social inclusion process (Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, & Kyriakidou, 2004). Future research can focus on community level coaching on ‘how to’ use apps like mHealth or facebook in social media and provide support to bring lifestyle changes through technological training solutions. Fostering community-based programs on technology skill development can reduce barriers to technology utilization and relieve the emotional stress of SI. For example, a simple training on how to use the ‘uber app’ can promote a feeling of independence and foster social interaction among the participants and the trainer. In the post COVID world, any group program, in an age friendly environment, at the community level for technology skills development itself would promote collaboration and social interaction to reduce SI among seniors. The possibilities of stress from isolation are automatically lowered when in person training sessions develop a sense of safety, security, and independence in older adults. Hence, the road to social support is a long-term approach at the community level with a focus on individual outcomes. Again, any form of technology-based intervention like internet based health care or telephone communication for social support would require the older adults to be involved with the community partners and stakeholders in the needs assessment and program development for successful implementation based on evidence in each context.

5. Strengths and Limitations

Our findings related to technology use and user confidence in this review relied only on self-reports and confidence in computer skills assessed after training interventions. The review did not cover the assessment of cognitive functioning in the older adults, which is an important component in acquiring technology skill. With diverse languages prevalent across countries, information accessibility is itself an important point of discussion in technology usage among older adults. We were limited to provide evidence of the importance of the cultural context and social relevance in the study of technology usage in both high- and low-income countries and within both. The heterogeneity of articles also limits the comparability and generalizability of our results across all aging populations across the globe. In fact, digitalization for older adults in the developing countries like Africa and Asia, especially in the rural regions, is highly dependent on the infrastructure and affordability (Schelenz & Schopp., 2018). Even in high income countries like United Kingdom, where older adults in general understand the language and can read and write, they may lack other skills such as basic electronic data processing knowledge needed to independently use technology, which is especially true for older women with limited technology literacy (Williams, Armitage, Tampe & Dienes., 2020). In this review, only articles in English were reviewed so, we were limited in evaluating technology interventions and strategies that are reported in non-English speaking countries. Also, the data on all articles in the review did not cover multiple levels of interpretation, so ambiguity remains as to whether technology use predicted social connectedness and better health outcomes, or whether already existing social connections and better health in the elderly predicted more technology use. Strengths of the review included a comprehensive search, transparent and standardized data extraction, screening procedures, and in-depth description and synthesis of data.

6. Conclusions

As the credibility in Internet information, knowledge, and experience are modifiable factors related to technology efficacy, the engagement of older adult at the community-level, following best practices from the Community-Based Participatory Research model is one good method of practice. Also, with technological advancement over the years, the effectiveness of interventions based on instant messaging apps like iMessage, What's App, Instagram Direct or Google Hangouts, needs to be meticulously examined to see how these can address the problem of SI. Results of such research can facilitate innovative and effective practice of technology-based SI interventions for elderly people.

Support for mental or physical health and livelihoods is needed for individuals undergoing SI in different regions. Hence, we need to emphasize on identifying how the older adults can most benefit from technology use and how the training and implementation of intervention can be tailored to maximize its effect. An integrated community-based approach with rolling-wave planning to find and support isolated seniors can be effective to respond to the needs and check the spread of isolation exacerbated with the COVID-19 pandemic. We need to find both online and offline resources and methods to improve accuracy and efficiency of interventions. This is possible when stakeholders, community partners and actors work in coordination to support the isolated or COVID quarantined seniors and help them make appropriate use of digital tools. In areas where per capita income is low and isolation exists in the local community in the US, public libraries, sometimes give access to technology use for health care services to the vulnerable populations (Curtis et al., 2006). Hence for seniors especially those with technology skill efficacy issues, there is a need to consider the educational, financial, and behavioral factors that affect the problem of SI.

Author statement

The first author conceived the research idea, carried out the analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. The Second and Third authors gave critical feedback on the general layout, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Financial disclosure

The research does not involve funding of any kind.

Declaration of competing interest

This work has not been published previously. It is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. The publication is approved by all authors. If accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically without the written consent of the copyright-holder.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Valery Armenta, MHA student at Texas State University, for the help with citations and edits on the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Keya Sen, Email: keyasen@txstate.edu.

Gayle Prybutok, Email: Gayle.Prybutok@unt.edu.

Victor Prybutok, Email: Victor.Prybutok@unt.edu.

References

- Ahn D., Shin D.H. Is the social use of media for seeking connectedness or for avoiding social isolation? Mechanisms underlying media use and subjective well-being. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(6):2453–2462. [Google Scholar]

- Amoah P.A. Social participation, health literacy, and health and well-being: A cross-sectional study in Ghana. SSM-Population Health. 2018;4:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baecker R., Sellen K., Crosskey S., Boscart V., Barbosa Neves B. Proceedings of the 16th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on Computers & accessibility. 2014. October). Technology to reduce social isolation and loneliness; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chai X., Kalyal H. Cell phone use and happiness among Chinese older adults: Does rural/urban residence status matter? Research on Aging. 2019;41(1):85–109. doi: 10.1177/0164027518792662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A.N., Downey J.P., McGaughey R.E., Jin K. Seniors and information technology in China. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction. 2016;32(2):132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman G.W., Gibson L., Hanson V.L., Bobrowicz A., McKay A. Proceedings of the 8th ACM conference on designing interactive systems. 2010, August. Engaging the disengaged: How do we design technology for digitally excluded older adults? pp. 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- Crombie I.K. John Wiley & Sons; 1996. Research in health care: Design, conduct and interpretation of health services research. [Google Scholar]

- Cudjoe T.K., Roth D.L., Szanton S.L., Wolff J.L., Boyd C.M., Thorpe R.J., Jr. The epidemiology of social isolation: National health and aging trends study. Journal of Gerontology: Series B. 2020;75(1):107–113. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis S., Copeland A., Fagg J., Congdon P., Almog M., Fitzpatrick J. The ecological relationship between deprivation, social isolation and rates of hospital admission for acute psychiatric care: A comparison of london and New York city. Health & Place. 2006;12(1):19–37. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja S.J., Boot W.R., Charness N., Rogers W.A., Sharit J. Improving social support for older adults through technology: Findings from the PRISM randomized controlled trial. The Gerontologist. 2018;58(3):467–477. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta A., Bhatia V., Noll J., Dixit S. Bridging the digital divide: Challenges in opening the digital world to the elderly, poor, and digitally illiterate. IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine. 2019;8(1):78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C., Alamanos E., Papagiannidis S., Bourlakis M. Does social exclusion influence multiple channel use? The interconnections with community, happiness, and well-being. Journal of Business Research. 2016;69(3):1061–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson A., Hill R.L. Keeping in touch: Talking to older people about computers and communication. Educational Gerontology. 2007;33(8):613–630. [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z., Cramm J.M., Jin C., Twisk J., Nieboer A.P. The longitudinal relationship between income and social participation among Chinese older people. SSM-Population Health. 2020;11:100636. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto R., Watanabe Y., Yamazaki A., Sugita M., Takeda S., Nakabayashi M., et al. Can digital health technologies exacerbate the health gap? A clustering analysis of mothers' opinions toward digitizing the maternal and child health handbook. SSM-Population Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Robert G., Macfarlane F., Bate P., Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J., Kim J., Won Y. Exploring the relationship between internet use and leisure satisfaction among older adults. Activities, Adaptation & Aging. 2011;35(1):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hill R., Betts L.R., Gardner S.E. Older adults' experiences and perceptions of digital technology:(Dis) empowerment, wellbeing, and inclusion. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;48:415–423. [Google Scholar]

- Holladay S.J., Seipke H.L. Communication between grandparents and grandchildren in geographically separated relationships. Communication References. 2007;58(3):281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson C.G., Doogan N.J. The impact of geographic isolation on mental disability in the United States. SSM-Population Health. 2019;8:100437. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsaker A., Hargittai E., Piper A.M. Online social connectedness and anxiety among older adults. International Journal of Communication. 2020;14:29. [Google Scholar]

- Ihm J., Hsieh Y.P. The implications of information and communication technology use for the social well-being of older adults. Information, Communication & Society. 2015;18(10):1123–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Jaana M., Pare G. Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii international conference on system sciences. 2020, January. Use of mobile health technologies for self-tracking purposes among seniors: A comparison to the general adult population in Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C.J., Bulot J., Johnson R.H. Outcome assessment of mentorship program. Educational Gerontology. 2008;34(7):555–569. [Google Scholar]

- Judges R.A., Laanemets C., Stern A., Baecker R.M. “InTouch” with seniors: Exploring adoption of a simplified interface for social communication and related socioemotional outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;75:912–921. [Google Scholar]

- Kadylak T., Makki T.W., Francis J., Cotten S.R., Rikard R.V., Sah Y.J. Disrupted copresence: Older adults' views on mobile phone use during face-to-face interactions. Mobile Media & Communication. 2018;6(3):331–349. [Google Scholar]

- Karanasios S., Cooper V., Adrot A., Mercieca B. Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii international conference on system sciences. 2020, January. Gatekeepers rather than helpless: An exploratory investigation of seniors' use of information and communication technology in critical settings. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns A., Whitley E. Associations of internet access with social integration, wellbeing and physical activity among adults in deprived communities: Evidence from a household survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):860. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse C., Fohn J., Wilson N., Patlan E.N., Zipp S., Mileski M. Utilization barriers and medical outcomes commensurate with the use of telehealth among older adults: Systematic review. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2020;8(8) doi: 10.2196/20359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelkes O. Happier and less isolated: Internet use in old age. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice. 2013;21(1):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley S.E., Harper R., Sellen A. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 2009, April. Desiring to be in touch in a changing communications landscape: Attitudes of older adults; pp. 1693–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Mitzner T.L., Stuck R., Hartley J.Q., Beer J.M., Rogers W.A. Acceptance of televideo technology by adults aging with a mobility impairment for health and wellness interventions. Journal of Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies Engineering. 2017;4 doi: 10.1177/2055668317692755. 2055668317692755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2021;134:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N.S. The relationship of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28(4):461–481. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A.R., De Schutter B., Franks K., Radina M.E. Older adults' experiences with audiovisual virtual reality: Perceived usefulness and other factors influencing technology acceptance. Clinical Gerontologist. 2019;42(1):27–33. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2018.1442380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelenz L., Schopp K. Digitalization in Africa: Interdisciplinary perspectives on technology, development, and justice. International Journal of Digital Society. 2018;9(4):1412–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S., Hampton A.J., Heinzel H.J., Felmlee D. Can I connect with both you and my social network? Access to network-salient communication technology and get-acquainted interactions. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;62:423–432. [Google Scholar]

- Sum S., Mathews R.M., Pourghasem M., Hughes I. Internet use as a predtechnology or of sense of community in older people. CyberPsychology and Behavior. 2009;12(2):235–239. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmage C.A., Knopf R.C., Wu T., Winkel D., Mirchandani P., Candan K.S. Decreasing loneliness and social disconnectedness among community-dwelling older adults: The potential of information and communication technologies and ride-hailing services. Activities, Adaptation & Aging. 2020:1–29. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print) [Google Scholar]

- Vošner H.B., Bobek S., Kokol P., Krečič M.J. Attitudes of active older Internet users towards online social networking. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55:230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Vroman K.G., Arthanat S., Lysack C. “Who over 65 is online?” Older adults' dispositions toward information communication technology. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;43:156–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhang R., Wellman B. Are older adults networked individuals? Insights from east yorkers' network structure, relational autonomy, and digital media use. Information, Communication & Society. 2018;21(5):681–696. [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.N., Armitage C.J., Tampe T., Dienes K. Public perceptions and experiences of social distancing and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A UK-based focus group study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]