ABSTRACT.

Human strongyloidiasis is one of the neglected tropical diseases caused by infection with soil-transmitted helminth Strongyloides stercoralis. Conventional stool examination, a method commonly used for diagnosis of S. stercoralis, has low sensitivity, especially in the case of light infections. Herein, we developed the droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) assay to detect S. stercoralis larvae in stool and compared its performance with real-time PCR and stool examination techniques (formalin ethyl-acetate concentration technique [FECT] and agar plate culture [APC]). The ddPCR results showed 98% sensitivity and 90% specificity, and real-time PCR showed 82% sensitivity and 76.7% specificity when compared with the microscopic methods. Moreover, ddPCR could detect a single S. stercoralis larva in feces, and cross-reactions with other parasites were not observed. In conclusion, a novel ddPCR method exhibited high sensitivity and specificity for detection of S. stercoralis in stool samples. This technique may help to improve diagnosis, particularly in cases with light infection. In addition, ddPCR technique might be useful for screening patients before starting immunosuppressive drug therapy, and follow-up after treatment of strongyloidiasis.

INTRODUCTION

Strongyloides stercoralis infection causes strongyloidiasis, which has long been a major public health problem. This parasite infects people in tropical and subtropical areas such as Africa, Latin America, Australia, and Asia.1 The highest prevalence of S. stercoralis infection is in Southeast Asia. For example, the reported prevalence of strongyloidiasis in Thailand ranges from 15.9% to 28.9%.2,3 In Khon Kaen, a province in northeastern Thailand, the infection rate is 12.9% according to examination of stool samples using formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique (FECT).4,5 Infected patients are primarily asymptomatic or have only mild gastrointestinal symptoms. However, in immunodeficient individuals or immunocompromised patients such as AIDS patients, alcoholics, and patients undergoing chemotherapy, there is a higher risk of developing severe disease because of autoinfection and dissemination to various organs.6–8 Therefore, a highly sensitive diagnostic technique is required to detect light infections, particularly in asymptomatic persons from endemic areas, before the administration of steroids or chemotherapy.

The diagnosis of S. stercoralis infections is currently based on traditional microscopic methods using stool samples, including the direct fecal-smear examination, FECT, Kato-Katz technique, Harada-Mori filter paper culture, and agar plate culture (APC). All these techniques are labor intensive, time consuming, and have low sensitivity. The APC technique can increase the sensitivity between 71.3% and 96%,9 but it is time consuming and requires fresh stool samples. Moreover, the APC is also unsuitable for detecting light infections because of the intermittent release of parasite larvae.10,11 Serological methods, such as ELISA, have been introduced but often produce cross-reactions with other helminth infections.12–14 Molecular techniques including PCR15,16 and real-time PCR17 have been developed to increase diagnostic sensitivity for strongyloidiasis. For instance, real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) offers high sensitivity compared with microscopic method.18

The third generation of PCR methodology has brought new molecular techniques including the droplet digital PCR (ddPCR).19,20 In ddPCR, the reaction mixture contains specific primers, fluorescent-labeled probes, or a double-strand DNA-binding dye. The mixture is divided into many partitions (droplets), each of which is individually amplified to endpoint. This technique can provide absolute quantification of target nucleic acid sequences based on Poisson statistics without external standards. The ddPCR approach can be used for the diagnosis of many parasitic diseases from various types of samples. Examples include detection of protozoan infections (Babesia microti and B. duncani) in blood of hamsters,21 Cryptosporidium oocysts in feces,22 Trypanosoma cruzi in blood,23 Plasmodium knowlesi and P. vivax in mosquitoes,24 and detection of the nematodes Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi in blood and mosquitoes.25 These studies have indicated that ddPCR has greater sensitivity and specificity than the real-time PCR assay. However, there is no previous report of the detection of S. stercoralis infection in fecal samples using the ddPCR technique. This study aimed to develop a ddPCR method for detection of S. stercoralis in fecal samples and compare its performance with microscopic methods and other molecular methods using clinical samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical statement and sample collection.

The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethical Review Committee of Khon Kaen University (HE631129). The collection of the human fecal specimens was performed as a part of the Cholangiocarcinoma Screening and Care Program (CASCAP), Khon Kaen University, Thailand. The study was carried out in two locations, Phu Wiang District, Khon Kaen Province, and Kamalasai District, Kalasin Province, Thailand, between November 2019 and June 2020. At the end of the study, S. stercoralis–infected individuals were treated with a single dose of 200 µg/kg of ivermectin.

Agar plate culture technique and worm collection.

The agar plate culture technique was used to detect S. stercoralis in stool samples as previously described.26 Approximately 2–4 g of individual fresh feces were placed at the center of an agar plate and incubated at 29–30°C in the dark. On the 3rd and 5th days after cultivation, worms, if present, were observed and collected under a stereomicroscope and transferred to a 15-mL tube with 1 mL of normal saline solution, followed by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes.

Formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique.

Individual fresh fecal samples of approximately 2–3 g were used and FECT performed as previously described.27,28 Strongyloides stercoralis larvae were double-blind counted by two investigators using compound microscopes and results presented as larvae per gram (lpg).28 The intensity of S. stercoralis infection was scored in three categories: 1–10, 11–50, and > 51 lpg for very light, moderate, and heavy infections, respectively.28

Spiking of human stool with S. stercoralis.

To evaluate the sensitivity of the ddPCR assay compared with other methods, we tested it using spiked stool samples. Third-stage larvae of S. stercoralis from cultures were collected and washed twice using phosphate-buffered saline solution. The various numbers of larvae (1, 2, 3, 5, or 10) were added to 200 mg of human stool known to be negative according to the FECT and APC techniques. This was done in triplicate. The DNA was extracted from these spiked aliquots of human stool and subjected to ddPCR.

Sources of DNA and DNA extraction.

Genomic DNA has been extracted from two types of samples: 1) filariform larvae of S. stercoralis collected from fecal larval cultures, and 2) individual human fecal samples from communities where strongyloidiasis is endemic (N = 80). The extracted DNA from filariform larvae was initially used for the development and optimization of ddPCR conditions. Then, DNA from human fecal samples was used to evaluate its diagnostic performance. No-template controls (NTCs) were run in parallel in all ddPCR assays, and 2 μL of template DNA was added in all reactions.

For the ddPCR method development and optimization, DNA was extracted from filariform larvae using DNeasy blood and tissue kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, larvae in normal saline were sonicated in an ice bath for 10 minutes at 20 kHz (VCX 750, Sonics & Materials Inc., Newtown, CT) and centrifuged at 13,500 rpm for 3 minutes at 4°C. Then, the supernatant was used for DNA extraction.

The DNA was extracted from 200 mg of each human fecal sample using the QIAamp PowerFaecal DNA Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The yield and purity of extracted DNA (absorbance ratio at 260/280) was determined using the NanoDrop 2000® (Nanodrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, NC). Until further use, DNA was stored at −20°C.

Primer and probe design.

Primers and probe were designed based on the gene sequence of the S. stercoralis 18S rRNA gene (GenBank accession no. M84229.1) using Primer3 software version 0.4.0 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/). Sequences of the primers and probe were as follows: forward 5′-CCGGACACTATAAGGATTGA-3′, reverse 5′-ACAGACCTGTTATCGCTCTC-3′, and probe FAM-5′-TCCGATAACGAGCGAGACTT-3′. Primer sequences for ddPCR were verified by conventional PCR, which gave 230 base pairs of PCR product. All primers and probes were synthesized by Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Thailand.

Real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR was used to amplify a region of the S. stercoralis 18S rRNA gene using the same primers described in the previous section. The real-time PCR conditions were optimized for primers without probe detection. The reaction mixture, with a total volume of 15 μL, contained with 5 μL LightCycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany), 1 μL of each primer (stock concentration 30 μM), 3 μL of distilled water, and 5 μL of DNA template. The amplification program consisted of 10 minutes at 95°C followed by 45 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, 1 minute at 60°C, and 30 seconds extension at 72°C. Amplification, detection, and data analysis were performed with a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Applied Science). The cycle threshold (Ct) value is defined by the number of PCR cycles required to detect the amplified products’ fluorescence signal.

Droplet digital PCR assay for S. stercoralis detection.

The primer pair and probe described in the Section “Primer and probe design” were used in the ddPCR method. Various annealing temperatures were tried for the ddPCR assay to determine the optimal conditions. In a total of 20 μL, the ddPCR reaction contained 10 μL of 2XddPCR Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), 1 μL of primers and probe, 2 μL of each DNA sample, and 7 μL of distilled water. This was added to the sample wells of the cartridge (Bio-Rad). Then 70 μL of droplet-generation oil was added to each well. Each reaction mix was converted to droplets with the QX200 droplet generator (Bio-Rad). All droplet-partitioned samples were transferred into a 96-well PCR plate and heat-sealed with foil using a PX1 PCR Plate Sealer (Bio-Rad). The amplification reaction, using a 100TM Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad), was under the following conditions: an initial step of 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, a gradient annealing temperature of 53.9–60°C for 1 minute, followed by 98°C for 5 minutes, and then a hold 4°C. The plate was read in the FAM channel using the QX200 Droplet Reader (Bio-Rad), and the data were analyzed using QuantaSoft software (Bio-Rad).

Analytical sensitivity and specificity of ddPCR.

The DNA extracted from filariform larvae of S. stercoralis was serially 10-fold diluted, starting with 5 × 10 ng/μL to 5 × 10−5 ng/µL. The ddPCR assay and real-time PCR were performed to determine the detection limit and reproducibility.

Cross-reactivity of the ddPCR assay was evaluated using DNA isolated from other parasitic worms that are common in northeastern Thailand29,30 including Hypoderaeum conoideum (N = 1), Centrocestus spp. (N = 1), and Taenia saginata (N = 1). Moreover, genomic DNA isolated from stool samples of patients infected with either Entamoeba coli (N = 1), Opisthorchis viverrini (N = 4), Blastocystis hominis (N = 3), echinostomes (N = 3), Trichuris trichiura (N = 1), and minute intestinal flukes (N = 2) were also included for cross reaction testing.

Statistical analysis.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and STATA version 10.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) was used to compare two detection methods (ddPCR and real-time PCR) to the microscopic methods. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of the tests were compared using 2 × 2 tables in STATA version 10.1. The guidelines of ROC for area under the curve (AUC) are as follows: 0.9–1.0 = excellent; 0.8–0.9 = good; 0.7–0.8 = fair; 0.6–0.7 = poor; and 0.5–0.6 = fail. Measures of agreement between detection methods (ddPCR and real-time PCR) with the microscopic methods were calculated using the Kappa statistic. Kappa statistical classification 0–0.20 = none, 0.21–0.39 = minimal, 0.40–0.59 = weak, 0.60– 0.79 = moderate, 0.80–0.90 = strong, and above 90 almost perfect agreement.31

RESULTS

Development of ddPCR assay.

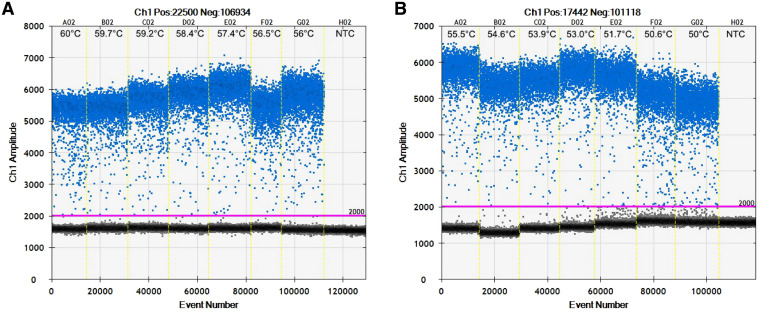

Using DNA extracted from S. stercoralis larvae, we optimized the parameters for the ddPCR assay. Samples with fewer than 10,000 droplets were not included in the analysis because inclusion would decrease the precision of the applied Poisson distribution. The annealing temperature was varied for the ddPCR assay to determine the optimal conditions, as shown in Figure 1. The experiment showed rain droplets or numerous droplets affecting cluster separation between positive cluster (blue points) and negative cluster (black points). The temperature of 56°C was chosen as the optimal annealing temperature. Positive or negative droplets were well separated and gave a high yield in the ddPCR assay.

Figure 1.

Optimization of annealing temperature in droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) assay using temperature-gradient PCR. Positive droplets obtained with the Strongyloides stercoralis-specific primer/probe set are shown in blue and negative droplets in black, separated from the positive droplets by manually adjustable threshold shown as a pink line. (A) shows results from ddPCR reactions with a gradient of annealing temperature of 56 to 60°C, and (B) shows temperatures from 50°C to 55.5°C. The yellow vertical dotted lines separate results from individual reaction wells. NTC = no target control. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

To examine the optimal DNA template volume in each reaction, we used various volumes of DNA template from clinical samples (1, 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 μL) at a template concentration of 5 ng/μL. This indicated that the appropriate range for calculating DNA target copies using the ddPCR assay was 1–8 μL. Thus, 2 μL of DNA template was used in all subsequent experiments for detection S. stercoralis DNA in clinical samples.

Sensitivity of ddPCR assay for S. stercoralis detection.

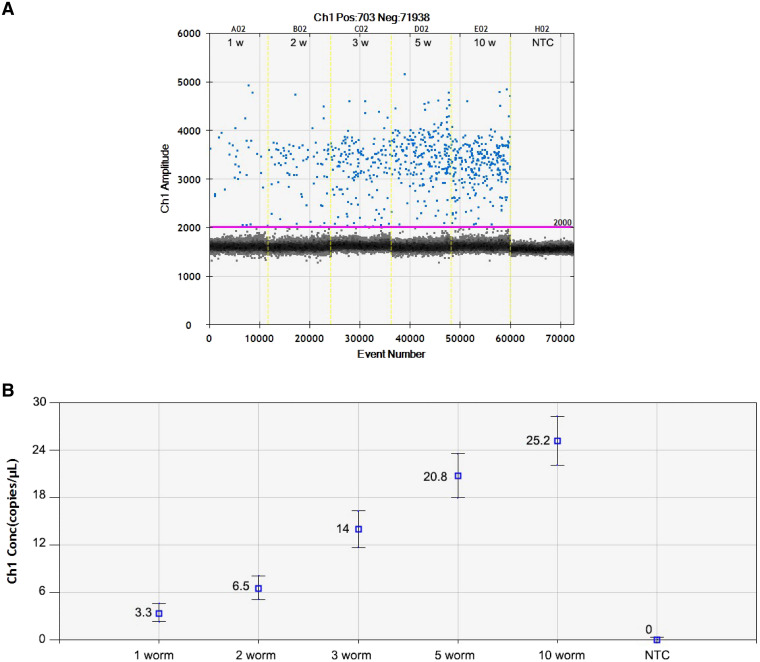

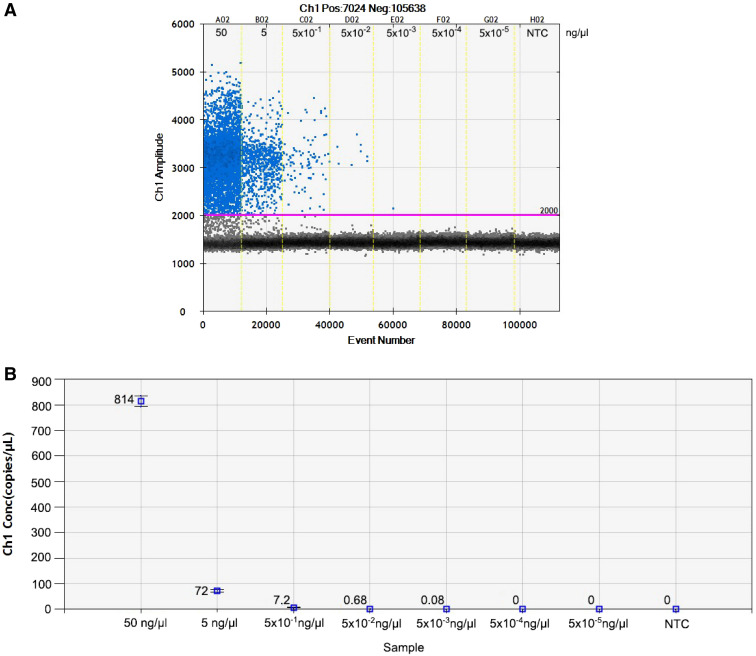

To evaluate the minimum detection level of the ddPCR assay, DNA was extracted from uninfected human stool spiked with larvae of S. stercoralis (1, 2, 3, 5, or 10 worms per sample) and subjected to duplicate independent runs. The results showed that the 18S rRNA target gene could be detected (3.3 copies/μL) in samples spiked with a single larva of S. stercoralis (Figure 2). Seven serial 10-fold dilutions from 50 to 5 × 10−5 ng/μL of S. stercoralis larvae DNA were analyzed in triplicate runs. The results revealed that the sensitivity of ddPCR assays was 5 × 10−3 ng/μL or equal to 0.08 copies of the target gene per microliter (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

(A) The one-dimensional (1D) droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) results of Strongyloides stercoralis 18S rRNA gene detection assay. Each ddPCR sample well is numbered according to the number of larvae used to spike 200 mg of Strongyloides-negative human stool (1, 2, 3, 5, or 10 worms). (B) The concentration of the 18S rRNA target gene (copies/μL) from Strongyloides-negative human stool samples (in triplicate) spiked with 1, 2, 3, 5, or 10 larvae, as above. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Figure 3.

The one-dimensional (1D) droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) results of the Strongyloides stercoralis detection assay. (A) The ddPCR sample wells is the amount of DNA in 10-fold serial dilutions starting from 50 ng/μL. (B) The concentration of the target gene (18S rRNA given in copies/μL) of S. stercoralis worm DNA in 10-fold serial dilutions. NTC = no target control. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Diagnostic strongyloidiasis performance of ddPCR in fecal samples.

A total of 80 fecal samples were processed for use in both microscopic methods (APC and FECT) and molecular methods (ddPCR and real-time PCR), as shown in Table 1. Microscopic methods, a reference method, identified S. stercoralis in 50 samples. Real-time PCR identified infection in 48 cases (cut-off at threshold > 35 cycles), whereas the ddPCR assay identified 52 positive cases, of which three samples were positive by ddPCR but negative by APC. In contrast, one case was negative by ddPCR but was positive by APC.

Table 1.

Comparison of the results obtained by the reference microscopic methods and molecular diagnostic methods for detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in 80 clinical stool samples

| Molecular methods | Reference method (APC + FECT) | Total (N = 80) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (N = 50) | Negative (N = 30) | |||

| ddPCR | Positive | 49 | 3 | 52 |

| Negative | 1 | 27 | 28 | |

| Real-time PCR | Positive | 41 | 7 | 48 |

| Negative | 9 | 23 | 32 | |

APC = agar plate culture; ddPCR = droplet digital polymerase chain reaction; FECT = formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique.

Further investigation was conducted on the three cases positive by ddPCR but negative by APC. These samples were tested using the ELISA technique following a previously published protocol,14,32 and all yielded positive results.

Using microscopic methods (either APC or FECT positive) as a standard, ddPCR showed higher sensitivity (98.0%; 95% CI = 89.4–99.9%) than real-time PCR (82.0%; 95% CI = 73.6–90.4%) and higher specificity (90%; 95% CI = 73.5–97.9%) than real-time PCR (76.7%; 95% CI; 67.4–85.9%). Analysis of area under the ROC curves revealed the test performance of ddPCR was 0.94 compared with microscopic methods. For comparison, the performance of real-time PCR was 0.79 when compared with microscopic methods. Statistics concerning diagnostic performance (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value) of ddPCR and real-time PCR are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the diagnostic performance of ddPCR and real-time PCR compared with the reference methods for detection of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in clinical samples (N = 80)

| Microscopic methods (APC + FECT) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tested method | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | AUC |

| ddPCR | 98.0% (89.4–99.9%) | 90.0% (73.5–97.9%) | 94.2% (84.1–98.8%) | 96.4% (81.7–99.9%) | 0.94 |

| Real-time PCR | 82.0% (73.6–90.4%) | 76.7% (67.4–85.9%) | 85.4% (77.7–93.1%) | 71.9% (62.0–81.7%) | 0.79 |

APC = agar plate culture; AUC = area under ROC curve; ddPCR = droplet digital polymerase chain reaction; FECT = formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique; NPV = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value.

To examine the efficiency of the test in light infections, we divided the infected participants into four groups (according to the numbers of larvae found using FECT) as follows: negative by FECT but positive by APC (FECT negative) (N = 31), 1–10 larvae (N = 12), 11–50 (N = 5), and > 51 larvae (N = 2). The results confirmed that ddPCR is more sensitive than real-time PCR. The ddPCR shows better sensitivity (96.8%; 95% CI: 83.3–99.9%) for detecting larvae in FECT-negative samples versus 83.9% (95% CI: 66.3–94.5%, P value < 0.001) for real-time PCR. Comparative values for all four categories are shown in Table 3, and consistently show that ddPCR is superior to real-time PCR.

Table 3.

Comparative efficacies of the test in microscopy (APC or FECT positive), ddPCR, and real-time PCR to detect Strongyloides stercoralis larvae in four categories according to the numbers of larvae found using FECT in stool samples

| Number of larvae present in the sample by FECT | Positive test results for S. stercoralis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of microscopy positive (APC + FECT) | Number of ddPCR positive (Sensitivity) (95% CI) | Number of real-time PCR positive (Sensitivity) (95% CI) | P-value | |

| 0 | 31 | 30 (96.8%) (83.3–99.9%) | 26 (83.9%) (66.3–94.5%) | < 0.001 |

| 1–10 | 12 | 12 (100.0%) (73.5–100.0%) | 9 (75.0%) (42.8–94.5%) | < 0.001 |

| 11–50 | 5 | 5 (100.0%) (47.8–100.0%) | 4 (80.0%) (28.4–99.5%) | < 0.001 |

| >51 | 2 | 2 (100.0%) (15.8–100.0%) | 2 (100.0%) (15.8–100.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Total | 50 | 49 | 41 | |

APC = agar plate culture; ddPCR = droplet digital polymerase chain reaction; FECT = formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique.

The extent of agreement between the three diagnostic techniques was assessed using kappa statistics. This revealed strong agreement (0.892) between ddPCR and microscopic methods (APC and FECT) and weak agreement (0.579) between real-time PCR and microscopic methods (Table 4).

Table 4.

Agreement (Kappa value) of diagnosis between the microscopic methods (APC and FECT) comparison with ddPCR and real-time PCR methods

| Variable | Kappa | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Microscopic vs. ddPCR | 0.892 | 0.777 | 0.974 | < 0.001 |

| Microscopic vs. real-time PCR | 0.579 | 0.391 | 0.748 | < 0.001 |

APC = agar plate culture; ddPCR = droplet digital polymerase chain reaction; FECT = formalin-ethyl acetate concentration technique.

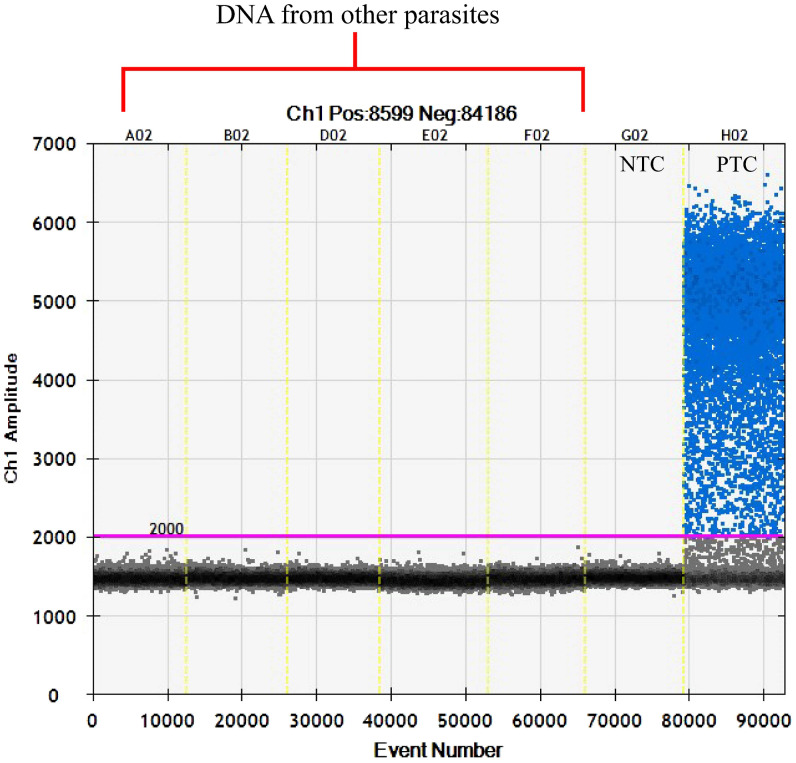

The ddPCR assay showed no cross-reactivity when DNA from other parasites was tested. These parasites were H. conoideum, Centrocestus spp., Taenia spp., O. viverrini, E. coli, B. hominis, echinostomes, T. trichiura, and minute intestinal flukes. The example of no-cross reactivity in ddPCR reaction is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The one-dimensional (1D) plot of droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) reactions using DNA extracted from parasites other than Strongyloides stercoralis. The DNA was extracted from Centrocestus spp. (A02), Hypoderaeum conoideum (B02), Blastocystis hominis (D02), Minute intestinal fluke eggs (E02, F02) (blue = positive droplets, gray = negative droplets, pink line = threshold at 2,000 fluorescent amplitude (NTC = no template control, PTC = positive template control with DNA of S. stercoralis larva). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of S. stercoralis infection in most clinical settings is underestimated either because of minimal larval output in feces or poor sensitivity of traditional parasitological methods.33,34 Thus, molecular diagnosis is required to detect chronic cases that might lead to the severe disease under immunodeficiency conditions. In this study, we newly developed and evaluated ddPCR assays for diagnosis of S. stercoralis in clinical stool samples. The new set of primers and probe that we designed represents a valuable new tool for diagnosis of S. stercoralis infection by ddPCR.

We determined the ability of ddPCR to detect worm DNA extracted from cultured third-stage larvae. Previous studies of real-time PCR have reported that the lower detection level of S. stercoralis spiked in stool was four larvae per 100 mg stool35 or 100 larvae per 200 mg stool.36 Our ddPCR assay could detect very low worm DNA template concentration (5 × 10−3 ng/µL, less than contained in one worm), making it an appropriate tool for diagnosing light infection.

The specificity of the assay is higher than previously reported assays, without cross-reactivity with DNA extracted from other parasite worms and the clinical fecal samples. This study revealed near-perfect agreement of ddPCR and microscopic methods for detecting S. stercoralis infection in human stool samples. This is consistent with many previous studies in other pathogens.37 In our study, ddPCR had 98% sensitivity and 90% specificity, higher sensitivity (82%) and specificity (76.7%) than shown by the real-time PCR assay. Many previous studies have reported that real-time PCR has lower sensitivity (63–84.7%) and specificity (79.1–95.8%)1,38,39 than our developed ddPCR method. The high specificity of our ddPCR assay may be because of the use of a target gene (18S rRNA) that is widely used to detect S. stercoralis in human fecal samples.18,35 As opposed to real-time PCR, ddPCR provides absolute quantification and is more sensitive and specific for low-abundance DNA. The quantitative accuracy of real-time PCR detection is acknowledged, but this required the use of a standard curve,40 whereas ddPCR gives quantitative accuracy without the need for standard curves.41 Similar results have been achieved when ddPCR was compared with real-time PCR in various diagnostic applications. In most cases, the former had higher sensitivity and accuracy than the latter.21 Interestingly, this study also showed that the advantages of ddPCR over real-time PCR was more apparent in light infections, successfully identifying infection in 96.8% of the cases negative by FECT but APC-positive. In contrast, real-time PCR only found 83.9% of these samples to be positive. Notably, three cases were negative by APC but were ddPCR and ELISA positive as a result of light infection and/or nonviable larvae produce the false-negative by APC.42 To confirm this contrary finding, examinations of several fecal specimens for 3 consecutive days is required this result.34

Although no cross-reactivities were observed, we did not extensively test the assay using additional species of parasites and samples from other geographical. Although ddPCR is the most sensitive diagnostic tool developed to date, this technique is relatively expensive, suggesting that further modification is required for routine diagnostic laboratory use.39,43 The method cannot be used directly in the field but may become an essential research tool or find a future role in follow-up after treatment with reduction of worm burden. The ddPCR assay may also find application to test other samples, such as urine, for presence of S. stercoralis infection.32,44

In conclusion, a ddPCR assay for diagnosis of strongyloidiasis was successfully developed. We have provided a proof of concept for this technology’s utility in detecting low intensities of infection. The ddPCR assay is significantly more sensitive and specific than microscopic methods (APC and FECT), and real-time PCR. Routine diagnosis using this technology is still a long way off resulting from various limitations, particularly the cost. Nevertheless, ddPCR may be a very valuable tool for research projects. It is particularly appropriate for detecting light infections, especially in immunocompromised individuals, and has application for monitoring after strongyloidiasis treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Prof. David Blair for editing the manuscript via Publication clinic Khon Kaen University, Thailand.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker SL. et al. 2015. Real-time PCR for detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in human stool samples from Cote d’Ivoire: diagnostic accuracy, inter-laboratory comparison and patterns of hookworm co-infection. Acta Trop 150: 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jongsuksuntigul P, Intapan PM, Wongsaroj T, Nilpan S, Singthong S, Veerakul S, Maleewong W, 2003. Prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in northeastern Thailand (agar plate culture detection). J Med Assoc Thai 86: 737–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nontasut P, Muennoo C, Sa-nguankiat S, Fongsri S, Vichit A, 2005. Prevalence of Strongyloides in northern Thailand and treatment with ivermectin vs. albendazole. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 36: 442–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beknazarova M, Whiley H, Ross K, 2016. Strongyloidiasis: a disease of socioeconomic disadvantage. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13: 517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasongdee TK, Laoraksawong P, Kanarkard W, Kraiklang R, Sathapornworachai K, Naonongwai S, Laummaunwai P, Sanpool O, Intapan PM, Maleewong W, 2017. An eleven-year retrospective hospital-based study of epidemiological data regarding human strongyloidiasis in northeast Thailand. BMC Infect Dis 17: 627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauber HP, Galle J, Chiodini PL, Rupp J, Birke R, Vollmer E, Zabel P, Lange C, 2005. Fatal outcome of a hyperinfection syndrome despite successful eradication of Strongyloides with subcutaneous ivermectin. Infection 33: 383–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mejia R, Nutman TB, 2012. Screening, prevention, and treatment for hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated infections caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 25: 458–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendes T, Minori K, Ueta M, Miguel DC, Allegretti SM, 2017. Strongyloidiasis current status with emphasis in diagnosis and drug research. J Parasitol Res 2017: 5056314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Requena-Mendez A, Chiodini P, Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D, Gotuzzo E, Munoz J, 2013. The laboratory diagnosis and follow up of strongyloidiasis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaves LA, Goncalves AL, Paula FM, Silva NM, Silva CV, Costa-Cruz JM, Freitas MA, 2015. Comparison of parasitological, immunological and molecular methods for evaluation of fecal samples of immunosuppressed rats experimentally infected with Strongyloides venezuelensis. Parasitology 142: 1715–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal V, Agarwal T, Ghoshal UC, 2009. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: a diagnosis frequently missed in the tropics. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 103: 242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bisoffi Z. et al. 2014. Diagnostic accuracy of five serologic tests for Strongyloides stercoralis infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buonfrate D. et al. 2015. Accuracy of five serologic tests for the follow up of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0003491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eamudomkarn C, Sithithaworn P, Sithithaworn J, Kaewkes S, Sripa B, Itoh M, 2015. Comparative evaluation of Strongyloides ratti and S. stercoralis larval antigen for diagnosis of strongyloidiasis in an endemic area of opisthorchiasis. Parasitol Res 114: 2543–2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paula FM, Malta Fde M, Marques PD, Sitta RB, Pinho JR, Gryschek RC, Chieffi PP, 2015. Molecular diagnosis of strongyloidiasis in tropical areas: a comparison of conventional and real-time polymerase chain reaction with parasitological methods. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 110: 272–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sitta RB, Malta FM, Pinho JR, Chieffi PP, Gryschek RC, Paula FM, 2014. Conventional PCR for molecular diagnosis of human strongyloidiasis. Parasitology 141: 716–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nadir E, Grossman T, Ciobotaro P, Attali M, Barkan D, Bardenstein R, Zimhony O, 2016. Real-time PCR for Strongyloides stercoralis-associated meningitis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 84: 197–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verweij JJ, Canales M, Polman K, Ziem J, Brienen EA, Polderman AM, van Lieshout L, 2009. Molecular diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in faecal samples using real-time PCR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 103: 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristanti H, Meyanti F, Wijayanti MA, Mahendradhata Y, Polman K, Chappuis F, Utzinger J, Becker SL, Murhandarwati EEH, 2018. Diagnostic comparison of Baermann funnel, Koga agar plate culture and polymerase chain reaction for detection of human Strongyloides stercoralis infection in Maluku, Indonesia. Parasitol Res 117: 3229–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miotke L, Lau BT, Rumma RT, Ji HP, 2014. High sensitivity detection and quantitation of DNA copy number and single nucleotide variants with single color droplet digital PCR. Anal Chem 86: 2618–2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson M, Glaser KC, Adams-Fish D, Boley M, Mayda M, Molestina RE, 2015. Development of droplet digital PCR for the detection of Babesia microti and Babesia duncani. Exp Parasitol 149: 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang R, Paparini A, Monis P, Ryan U, 2014. Comparison of next-generation droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) with quantitative PCR (qPCR) for enumeration of Cryptosporidium oocysts in faecal samples. Int J Parasitol 44: 1105–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramirez JD, Herrera G, Hernandez C, Cruz-Saavedra L, Munoz M, Florez C, Butcher R, 2018. Evaluation of the analytical and diagnostic performance of a digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) assay to detect Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in blood samples. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12: e0007063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahendran P, Liew JWK, Amir A, Ching XT, Lau YL, 2020. Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) for the detection of Plasmodium knowlesi and Plasmodium vivax. Malar J 19: 241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jongthawin J, Intapan PM, Lulitanond V, Sanpool O, Thanchomnang T, Sadaow L, Maleewong W, 2016. Detection and quantification of Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi DNA in blood samples and mosquitoes using duplex droplet digital polymerase chain reaction. Parasitol Res 115: 2967–2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sithithaworn P, Srisawangwong T, Tesana S, Daenseekaew W, Sithithaworn J, Fujimaki Y, Ando K, 2003. Epidemiology of Strongyloides stercoralis in north-east Thailand: application of the agar plate culture technique compared with the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 97: 398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elkins DB, Haswell-Elkins MR, Mairiang E, Mairiang P, Sithithaworn P, Kaewkes S, Bhudhisawasdi V, Uttaravichien T, 1990. A high frequency of hepatobiliary disease and suspected cholangiocarcinoma associated with heavy Opisthorchis viverrini infection in a small community in north-east Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 84: 715–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anamnart W, Intapan PM, Maleewong W, 2013. Modified formalin-ether concentration technique for diagnosis of human strongyloidiasis. Korean J Parasitol 51: 743–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boonjaraspinyo S, Boonmars T, Kaewsamut B, Ekobol N, Laummaunwai P, Aukkanimart R, Wonkchalee N, Juasook A, Sriraj P, 2013. A cross-sectional study on intestinal parasitic infections in rural communities, northeast Thailand. Korean J Parasitol 51: 727–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eamudomkarn C, et al. 2018. Diagnostic performance of urinary IgG antibody detection: a novel approach for population screening of strongyloidiasis. PLOS ONE 13: e0192598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHugh ML, 2012. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 22: 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruantip S, Eamudomkarn C, Techasen A, Wangboon C, Sithithaworn J, Bethony JM, Itoh M, Sithithaworn P, 2019. Accuracy of urine and serum assays for the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis by three enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay protocols. Am J Trop Med Hyg 100: 127–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dreyer G, Fernandes-Silva E, Alves S, Rocha A, Albuquerque R, Addiss D, 1996. Patterns of detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in stool specimens: implications for diagnosis and clinical trials. J Clin Microbiol 34: 2569–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uparanukraw P, Phongsri S, Morakote N, 1999. Fluctuations of larval excretion in Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 60: 967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janwan P, Intapan PM, Thanchomnang T, Lulitanond V, Anamnart W, Maleewong W, 2011. Rapid detection of Opisthorchis viverrini and Strongyloides stercoralis in human fecal samples using a duplex real-time PCR and melting curve analysis. Parasitol Res 109: 1593–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kramme S, Nissen N, Soblik H, Erttmann K, Tannich E, Fleischer B, Panning M, Brattig N, 2011. Novel real-time PCR for the universal detection of Strongyloides species. J Med Microbiol 60: 454–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koepfli C, Nguitragool W, Hofmann NE, Robinson LJ, Ome-Kaius M, Sattabongkot J, Felger I, Mueller I, 2016. Sensitive and accurate quantification of human malaria parasites using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). Sci Rep 6: 39183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sultana Y, Jeoffreys N, Watts MR, Gilbert GL, Lee R, 2013. Real-time polymerase chain reaction for detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in stool. Am J Trop Med Hyg 88: 1048–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buonfrate D, Requena-Mendez A, Angheben A, Cinquini M, Cruciani M, Fittipaldo A, Giorli G, Gobbi F, Piubelli C, Bisoffi Z, 2018. Accuracy of molecular biology techniques for the diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection-A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12: e0006229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu Z, Zhao Z, Chen L, Li J, Ju X, 2020. Development of a droplet digital PCR for detection of Trichuriasis in sheep. J Parasitol 106: 603–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H. et al. 2018. Application of droplet digital PCR to detect the pathogens of infectious diseases. Biosci Rep 38: BSR20181170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato Y, Kobayashi J, Toma H, Shiroma Y, 1995. Efficacy of stool examination for detection of Strongyloides infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 53: 248–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon CA, Gray DJ, Gobert GN, McManus DP, 2011. DNA amplification approaches for the diagnosis of key parasitic helminth infections of humans. Mol Cell Probes 25: 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weerakoon KG, Gordon CA, Williams GM, Cai P, Gobert GN, Olveda RM, Ross AG, Olveda DU, McManus DP, 2017. Droplet digital PCR diagnosis of human schistosomiasis: parasite cell-free DNA detection in diverse clinical samples. J Infect Dis 216: 1611–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]