Abstract

Recruitment and retention of a diverse physician population across stages of medical education is essential for the success of the healthcare system. MedFTs have a unique role to play in advocacy and intervention related to the recruitment and retention of these physicians at all stages of their education and career. As MedFTs expand their influence in healthcare systems, they must ground into their fundamental theories, like systems theory and the Four World View, all while advancing in their professional competencies to attune their skills and those whom they are entrusted in training. The conceptual model, MedFTs’ Role in the Recruitment and Retention of a Diverse Physician Population, provides a framework for MedFTs to use their influence to enact change related to diversity and equity in the healthcare system. In addition, the model provides avenues for intervention and advocacy on the part of the MedFT related to each of the four worlds and their specific role(s) in the health care.

Keywords: Medical Family Therapy, Diversity, Medical education, Four World View, Competencies

Introduction

The United States (U.S.) healthcare system is in a state of crisis. Burnout was already considered a key concern for physician and health system wellness prior to 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this with 55% of frontline healthcare workers indicating they are experiencing it (Kaushik, 2021). In addition, the Association for American Medical Colleges (AAMC) projects physician shortages between 17,800 and 77,100 by the year 2034, making the retention and recruitment of physicians central to maintaining and strengthening the healthcare system (AAMC, 2021a, b, c). Further, systemic inequities and the lack of representation in diverse physicians’ social locations (race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, sex, etc.) in relation to patient populations are consistent concerns in health care. These concerns must be a priority for all who interact with the healthcare system because a plentiful and diverse physician population is beneficial to all patients and families.

Medical Family Therapists (MedFTs) have the responsibility to intervene on behalf of diverse recruitment and retention practices in their scopes of influence. The intent of this article is to address the critical need to recruit and retain medical students, residents, and practicing physicians that represent the demographics of patients who receive health care in the U.S. and give recommendations to MedFTs working in healthcare systems on ways to influence change related diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

The current state of retention and recruitment of diverse physician populations in the U.S. is of significant concern. For example, Black/African American physicians at all stages of education are significantly underrepresented related to the U.S. population (13.4% U.S. population, 5% practicing physicians, 5.5% residents, and 9.4% medical students; AAMC, 2018, 2019a, 2020, 2021a, c; U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Similarly Hispanic/Latinx/or Spanish Origin physicians are underrepresented (18.5% U.S. population, 5.8% practicing physicians, 7.5% residents, and 12% medical students; AAMC, 2018, 2019a, 2020, 2021a, c; U.S. Census Bureau, 2019; see Table 1).1 In addition, women make up just over half of the U.S. population (50.1%) but make up only 36.3% of practicing physicians (AAMC, 2019b). Further, 5.6% of the U.S. identifies as sexual and gender minorities and yet representation among medical students, residents, and practicing physicians are often neglected from recruitment or retention reports (Jones, 2021; U.S. Census Bureau, 2019; See Table 1).

Table 1.

Race/Ethnicity by training level compared to U.S. general population

| Race/ethnicity | Medical school (2020) | Residency (2021) | All practicing physicians (2018) | US general population (2019; 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0.3% | 1.3% |

| Asian | 24.8% | 21.8% | 17.1% | 5.9% |

| Black/African American | 9.4% | 5.5% | 5% | 13.4% |

| Hispanic/Latino/or Spanish Origin | 12% | 7.5% | 5.8% | 18.5% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| White | 53.6% | 50.8% | 56.2% | 60.3% |

| Other | 4.9% | NR | 0.8% | NR |

| Unknown | 1.5% | NR | 13.7% | NR |

| Sex (female) | 47.9% | 45.6% | 36.3% | 50.1% |

| LGBTQ+ |

Bisexual 5%; Gay/Lesbian 3.8%; Gender other than what is assigned at birth 0.7% |

NR | NR | 5.6% |

Representation in health care is important for multiple reasons, including social concordance in patient-physician relationships (i.e., similar characteristics such as race/ethnicity, sex, or sexual orientation/gender identity) which influences trust and shared decision making with the potential to improve patients’ quality of care (Kurek et al., 2016; Thornton et al., 2011). In addition, increased representation of diverse populations in health care has been shown to improve communication between physicians and their colleagues as well as between physicians and patients (Hughes et al., 2018; University of St. Augustine, 2021). Specifically, diverse workforce across the healthcare system has been shown to increase the understanding of varied values and beliefs about health (University of St. Augustine, 2021), and representation of diverse social locations in the healthcare system are essential for recruitment, training, and retention a diverse population of medical students, residents, and practicing physicians from groups that are currently and historically marginalized in the U.S. (Garces & Mickey-Pabello, 2015). Creating a diverse and inclusive healthcare system is, in part, the responsibility of all who interact within it.

MedFTs are uniquely situated to address systems-based disparities and inequities through their systemic training. This systemic lens makes it possible for MedFTs to be aware of the numerous inequities that exist in the lives of physicians, particularly with historically marginalized or systemically oppressed physicians, at all stages of education and practice. In addition, MedFTs’ systemic training has equipped them to act as agents of change to promote and sustain a more equitable, inclusive, and diverse future for physicians in health care.

It is the aim of this article to (a) represent both the history and future directions of MedFT as a field in context of the MedFT Health Care Continuum (MedFT-HCC; Hodgson et al., 2018); (b) discuss how the competencies for family therapists working in healthcare settings (AAMFT, 2018) and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Milestones (ACGME, 2021) serve as a base toward strengthening diversity and inclusion in health care, specifically related to recruitment and retention; (c) use fundamental theories that ground MedFT, and frameworks such as the Four World View (Peek, 2008) to reimage how healthcare systems can construct recruitment and retention plans with diverse medical students, residents, and physicians from historically marginalized groups; (d) bring attention to recruitment and retention data across medical educational and career stages; (e) offer a conceptual model that integrates intersectionality and the Four World View across the education and career development of physicians; and (f) provide examples of ways in which MedFTs can use their spheres of influence to enact change related to recruitment and retention of a diverse physician population.

Medical Family Therapy: History and Future Directions

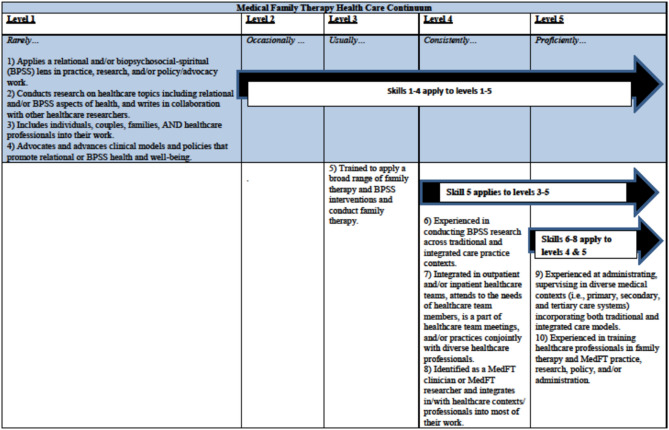

Over the past 30 years, the field of MedFT has grown from a strong base of systemically trained therapists working in healthcare settings to include other advanced roles such as funded researchers, trainers, policy makers, and administrators across various healthcare contexts (e.g., primary, secondary, and tertiary settings; McDaniel et al., 1992, 2014). In 2018, a range of possibilities for MedFTs was illustrated via the MedFT Health Care Continuum (MedFT-HCC; Hodgson et al., 2018; see Table 2). The MedFT-HCC spans across five levels of experience and training in relational theories in tandem with the biopsychosocial spiritual (BPSS) framework, with higher levels of proficiency affording broader opportunities for MedFTs in the workforce.

Table 2.

Medical Family Therapy Health Care Continuum

Hodgson et al., 2018

In the early history of MedFT, fewer professionals were engaged in the field, and therefore their ability to enact higher order change in healthcare systems was limited. As time progressed, more MedFTs have come through advanced MedFT training programs (including master’s programs, institutes, and doctoral programs) and taken positions such as behavioral health directors and faculty members in medical schools or residencies. In these positions, MedFTs are charged with collaboration, education, training, recruitment, and retention of physicians across all stages of their training and practice (e.g., medical students, residents, and practicing physicians), making it essential for MedFTs to engage with their own competencies and the competencies of those they are teaching and collaborating with.

A New Era

Through the growth in job opportunities for MedFTs, a new era of influence and systemic change has emerged. In 2018, a series of competencies spanning from beginner to advanced level were developed to impress the importance of clinical skills, scholarship, training/supervision, and healthcare management/policy (Competencies for Family Therapists Working in Health Care; AAMFT, 2018; see Table 3). Six anchoring domains coincided with the MedFT competencies, including (a) Systems, (b) BPSS, (c) Collaboration, (d) Leadership, (e) Ethics, and (f) Diversity.

Table 3.

Competencies for Family Therapists Working in Healthcare Settings

| Domain 1: Systems |

1.1 Clinical skills 1.2 Training and supervision 1.3 Healthcare management and policy 1.4 Scholarship |

| Domain 2: Biopsychosocial-spiritual |

2.1 Clinical skills 2.2 Training supervision 2.3 Healthcare management and policy 2.4 Scholarship |

| Domain 3: Collaboration |

3.1 Clinical skills 3.2 Training supervision 3.3 Healthcare management and policy 3.4 Scholarship |

| Domain 4: Leadership |

4.1 Clinical skills 4.2 Training supervision 4.3 Healthcare management and policy 4.4 Scholarship |

| Domain 5: Ethics |

5.1 Clinical skills 5.2 Training supervision 5.3 Healthcare management and policy 5.4 Scholarship |

| Domain 6: Diversity |

6.1 Clinical skills 6.2 Training supervision 6.3 Healthcare management and policy 6.4 Scholarship |

AAMFT, 2018

When recruiting and retaining physicians throughout their education and career trajectories, MedFTs must not only attend to their own competencies (AAMFT, 2018) but also to competencies related to medical students, residents, and practicing physicians ACGME Milestones; ACGME, 2021; see Table 4). The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education put in place the ACGME Milestones to provide core competencies for the training and practice of physicians. This initiative began in 1999, with all specialties using and reporting to the ACGME Milestones in 2015. Core competencies outlined in the ACGME Milestones remain the same for each specialty, but some of the nuances of measurement and specific skills vary by specialty. The purpose of these milestones is to set in place basic skills needed to practice medicine, from medical knowledge and patient care to systems-based care and interpersonal skills.

Table 4.

ACGME Milestones

| Competency | Examples of sub competencies based on family medicine milestones |

|---|---|

| Competency 1- Practice-based learning and improvement |

1. Patient care of acutely ill patient 2. Care of patients with chronic illness 3. Health promotion and wellness 4. Ongoing care of patients with undifferentiated signs, symptoms or concerns 5. Management of procedural care |

| Competency 2- Patient care and procedural skills |

1. Evidence based and informed practice 2. Reflective practice and commitment to personal growth |

| Competency 3- System-based practice |

1. Patient safety and quality improvement 2. System navigation for patient-centered care 3. Physicians role in health care systems 4. Advocacy |

| Competency 4- Medical knowledge |

1. Sufficient medical knowledge of family medicine 2. Critical thinking/decision making |

| Competency 5- Interpersonal and communication skills |

1. Patient and family centered communication 2. Interprofessional and team communication 3. Communication within health care systems |

| Competency 6- Professionalism |

1. Professional behavior and ethical principles 2. Accountability/conscientiousness 3. Self-awareness and help-seeking |

ACGME milestones include six competencies and sub competencies that fall under these, based on specialty. Examples given in this table are drawn from the family medicine milestones (ACGME, 2021)

Using the ACGME Milestones (ACGME, 2021) and Competencies for Family Therapists Working in Healthcare Settings (AAMFT, 2018) as resources, MedFTs are able to maximize their ability to attend to systemic and structural facilitators and barriers in relation to recruitment and retention of physicians from historically marginalized groups. For example, when MedFTs are fluent in competencies pertaining to diversity that are core to each discipline, they can better advocate for change in a system or organizational context. Diversity and equity are reflected throughout the Competencies for Family Therapists Working in Healthcare Settings (and specifically in Domain 6; AAMFT, 2018), but also to the ACGME Milestones Competency 2: Patient care, Competency 3: Systems-based practice, and Competency 5: Interpersonal and communication skills.

These competencies and milestones provide ways to guide current and future MedFTs and medical students, residents, and practicing physicians in their attention to DEI. However, growth must not be limited only to these domains or milestones. DEI is not an add-on lecture, course, or skillset, but rather requires ongoing self-reflection, trainings by DEI experts, peer debriefing, and mentorship discussions with a commitment to cultural awareness, sensitivity, attunement, and humility in relation to all social locations. MedFTs, regardless of whether DEI was emphasized in their programs, have the responsibility to address their own biases and beliefs, then advocate for DEI to be included in MedFT curricula, professional trainings for physicians, and as part of all recruitment and retention practices that span the career of current and future physicians. It is through a commitment to DEI, along with foundational theories and frameworks, that MedFTs can best advocate for systemic change in physician recruitment and retention practices.

Systems Thinking and the Four World View

As MedFT moves into a new era, a core component of MedFT training remains consistent: a foundational lens through systems theory. Systems theory was first introduced by von Bertalanffy (1968), with foci including nonsummativity (i.e., the whole is greater than the sum of the parts) and that a change in one part or unit would influence a change in all others. In MedFT, systems theory plays an essential role in understanding how interlocking systems influence each other in health care. In order to best understand the role of interlocking systems, the Four World View developed by Peek (2008) provides a framework to consider each world of health care and its importance to the healthcare system as a whole.

The Four World View includes the clinical, operational, financial, and training/education worlds. Each world is seen as necessary to sustain a successful healthcare system. The clinical world focuses on direct patient care and, particularly, on the provision of quality care for patients related to their encounter with their provider. The operational world embodies the organizational, policies and protocol, as well as workflow and documentation portals of the healthcare system. The operational world is essential to keep the healthcare system running as efficiently as possible; this includes things like scheduling and ordering supplies. The financial world comprises payment, reimbursement, and billing systems; this world ensures that providers are compensated, insurance is billed on behalf of patients, and funds are managed ethically and accurately. Lastly, the training/education world includes the training of new professionals and delivery of continuing education for providers within healthcare systems. This includes medical school, residency, fellowships, and continuing education for practicing physicians. Without each world working together to keep the healthcare system functioning optimally, the system would collapse. MedFTs’ systemic training affords a lens to see all of these worlds simultaneously, thus enhancing opportunities for patients, providers, and the healthcare system concurrently.

Diversity in Medicine Across Career Stages

It is important for MedFTs to not only be trained in systems theory, the Four World View, and in competencies and milestones; they must also recognize how these theories and indicators of proficiency play out systemically in the lives of physicians across each career stage. Furthermore, MedFTs must be prepared to discern the unique needs of diverse learners. In order to best understand the experiences of historically marginalized physicians, it is important to view their experiences through a lens of intersectionality.

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework to understanding the experiences of individuals with multiple marginalized identities in context of or in contrast to those with privileged identities or with only one marginalized identity. Intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) provides a lens to examine the cumulative effects of multiple marginalized identities and the ways in which these experiences influence an individual’s lived experience. For example, prior to the introduction of intersectionality, experiences of being Black were primarily understood within the context of Black males and experiences of being female were only captured within the context of White females. In other words, sex and race were seen as mutually exclusive experiences rather than qualitatively different experiences related to multiple marginalized identities. This siloed perspective did not adequately capture the holistic experiences of those who identified as Black and/or those who identified as female (Crenshaw, 2017).

When looking at DEI throughout each stage of education and career for physicians, it is essential to see how the intersecting identities of physicians uniquely influence their experiences in medicine. Many times, data on race/ethnicity do not include a break down by sex. If there is a break down by sex and/or gender, it is often viewed as binary (i.e., male and female) with no option to choose another option, further limiting the ability for the data to capture experiences of those who identify outside of binary descriptors. In addition, many social locations are almost completely absent in national data for medical students, residents, and/or practicing physicians, including ability and citizenship status. Keeping the lens of intersectionality in mind, the following section will discuss the stages of training from pre-medical school to practicing physicians, including their experiences related to representation of race/ethnicity, sex, and sexual orientation/gender identity compared to the general public, and common systemic barriers and requirements that factor into the lack of diversity among U.S. physicians.

Prior to Medical Education

In order to grasp the social location inequities and representation of physicians related to the general public, it is first important to look at both those who apply to and attend medical school and residency as well as those who did not. It may benefit MedFTs to understand the requirements necessary to apply for medical school to gain insight into some of the reasons for inequitable representation in medical school and beyond. Students must have a bachelor’s degree in a related field (e.g., premed, biology) and take the Medical School Admission Test (MCAT). Prior to this, students must finish high school or complete the equivalency, take necessary admittance tests to get into a college or university, and attend and finance a bachelor’s degree. In addition to the longstanding controversies pertaining to standardized testing, it is estimated that the cost of a bachelor’s degree, including loss of income and student loan interest is $400,000 (Hanson, 2021).

Beyond the cost of a four-year degree, pre-med majors must overcome a series of systemic barriers to be admitted into medical school. Recent data suggest that first generation students (i.e., students whose parents do not hold a four-year degree or equivalent) are less likely to use university services such as health care, academic advising, or support services, and more likely to take out greater loans while enrolled at a university (RTI International, 2019). First generation students have a median parental income that is $50,000 dollars less than students who come from parents who have college degrees. According to the Department of Education, 28% of White students are first generation college students, while 42% of Black/African American students and 48% of Hispanic/Latino/or Spanish Origin students are first generation students (Postsecondary National Policy Institute [PNIP], 2021). When considering the many complexities of starting and completing higher education, it is clear that entrance into medical school is not equitable for racial/ethnic and other students from marginalized groups who desire to become physicians.

Medical Education

Medical school is a post graduate degree that provides learners with the skills necessary to become a physician. The typical length of medical school is four years. At the point of graduation, students will have earned their Medical Doctorate (MD) or Doctorate in Osteopathic Medicine (DO). Medical school ranges in price based on in-state or out-of-state tuition, as well as whether attendance was at a private or public institution. The average price of medical school per year is $34,592 for in-state students, $58,668 for out-of-state students, and well over $50,000 per year for most private institutions. The average student debt after four years of medical school is $176,348 with 43% of medical students accumulating over $200,000 in student loans (Kaplan, N.D). When thinking about the financial cost of medical school, one must also consider the price of entrance exams, standardized testing (MCAT), application fees, travel for admission interviews, costs of living, books, equipment, and the diminished ability to hold a full or part time job.

There are currently 192 medical schools in the U.S., and for the 2020–2021 school year, 53,030 students applied, and 23,105 students were accepted. The racial/ethnic distribution of accepted students was as follows: 1.1% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 24.8% Asian, 9.4% Black/African American, 12% Hispanic/Latinx/or Spanish Origin, 0.04% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 53.6% White non-Hispanic, 4.9% Unknown, 3.8% Other, and 1.5% Non-U.S. Citizen (note that these demographics will not add to 100% because these race/ethnic categories may be one’s sole race/ethnicity or in combination with another racial/ethnic identity; AAMC, 2020).

These statistics can be better understood in context of the demographics of the U.S. general population and to other stages of physician training (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019; see Table 1). These data are encouraging as a significant increase is witnessed in Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx/or Spanish Origin students compared to the most recent diversity data for residents or practicing physicians, but clearly remain deficient in contrast to their representation in the U.S. general population. There is concern about the lack of representation for Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino/or Spanish Origin students related to the general population, even with increasing admittance into medical school. Black/African Americans make up 13.4% of the general public but only 9.4% of medical students. Similarly, Hispanic/Latinx/or Spanish Origin people make up 18.5% of the U.S. population, but only 12% of medical students (AAMC, 2020; U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). This leaves room for increased parity in Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx/or Spanish Origin medical students compared to the general population.

Statistics based on 2018–2019 data for sex shows women make up 50.9% of applicants to medical school, 51.6% of matriculates, but only 47.9% of graduates. This attrition is not mirrored by men in medical school (AAMC, 2019b). Demographics on sexual and gender identity were not collected until 2016 for the AAMC (Leggott, 2020) and until 2018 for the American Medical Association [AMA] (AMA, 2018). In 2019, 5% of medical students identified as bisexual, 3.8% identified as gay or lesbian, and 0.7% identify as a gender different than their gender assigned at birth (Leggott, 2020). Even with the impetus from the AAMC and AMA, any data related to sexual and gender marginalized medical students may or may not be accurate due to fear or stigma in reporting sexual orientation or gender identity in medical school.

A Stanford University study reported that one third of sexual and gender marginalized students choose not to disclose their gender identity or sexual orientation, and 40% feared discrimination if others found out about their identity. However, there are exemplars in the medical school system related to sexual and gender representation among medical students (White, 2015). For example, the 2019–2020 incoming class of medical students at Harvard Medical School reported 15% of students identifying as belonging with an underrepresented sexual and gender social location(s), indicating a shift in priorities when it comes to representation and inclusion (American Society of Hematology [ASH], 2020). This shift reflects important systemic change in the diversity of the upcoming physician workforce (if retention of students is considered as important as recruitment). Harvard Medical School may well be setting a standard for diversity and inclusion among other institutions and patients will benefit from seeing and being treated by these future physicians.

Data related to medical school attendance are essential to understanding diversity in the physician workforce, but it is also important to look at retention and graduation rates. From 1993 to 2013, the graduation rate of medical students in a four-year time frame ranged from 81.6% to 84.3% with an average graduation rate after 6 years of 95.9%. Note, too, that graduating in four years from medical school is not always the goal. Many students take longer and complete additional training such as a Master’s in Public Health (MPH), Master’s in Business Administration (MBA), or a Doctoral Degree (Ph.D.). In total, the attrition rate for the last 20 years has been about 3.3% (AAMC, 2018). There were no known attrition rates available by race/ethnicity, sex, or sexual orientation/gender identity.

Residency

Residency is a post medical education program that allows new physicians to give direct patient care, gain experience, and complete requirements such as board certifications needed to practice independently. Medical students interview with residencies in their final year of medical school, then rank their choices based on where they would like to attend. Residency programs do the same, and then an algorithm is used to match residents to a program. During residency, residents often work 80 h per week. This 80 h cap was implemented in 2003 by the AMA to prevent burnout, physician suicide, and patient care errors (Philibert et al., 2009). Residents are often working at all hours of the day, and frequently bump up against this hour cap. The length of residency depends on the field of practice; it ranges from 3 to 7 years. During this time, residents are paid for their work with an average salary of $63,400, depending on area of the country and specialty. It is important to note that residents are required to pay toward their student loans during residency, alongside their costs of living (Gooch, 2020).

There are currently 139,848 medical residents in the U.S. (AAMC, 2021c). In 2021, there were 42,508 applicants to residency programs and 38,106 positions in residency programs to be filled. A total of 5915 residency programs participated in the match. Out of the 38,106 positions available, 36,179 were filled, making it a record year for residents and residency programs (National Resident Matching Program [NRMP], 2021a). Data on race/ethnicity in residency for the 2019–2020 year are as follows: 0.6% as American Indian or Alaska Native, 21.8% identify as Asian, 5.5% as Black or African American, 7.5% as Hispanic/Latinx/ or Spanish Origin, 0.2% as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander and 50.8% of White non-Hispanic residents (note this does not include international students and that residents could choose more than one race; AAMC, 2021a).

While there are significant increases in diversity in medical school admittance for Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx/or Spanish Origin individuals, the same is not seen in residency. In residency, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Black/African American, and Hispanic/Latinx/or Spanish Origin residents make up less than half of what would be expected based on the general U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). In addition, according to 2018 data, 54.4% of the total U.S. medical residents identified as men and 45.6% identified as women. The number of women residents is increasing, and in 2019 the number of women students entering medical school outnumbered men students for the first time ever, which is promising for parity in the number of women physicians in the coming years (AAMC, 2019b). Inclusive sexual and gender data for residents are not currently reported.

While trends in medical school attendance are promising for representation in context of the U.S. general population, it will likely take several years before the current cohort of medical students reach residency. Unfortunately, attrition affects both medical students and residents, specifically among residents from marginalized groups. While there is little research on racially diverse and ethnically diverse residents, research does reflect higher attrition rates among residents from historically marginalized and systemically oppressed social locations (e.g., attrition rates for emergency residents were found as follows: Hispanic/Latinx 1.82%, Black 1.22%, American Indian/Alaska Native 1.21%, Asian 1.11%, and White non-Hispanic 0.88% (Lu et al., 2019). Little is shared about the ways in which the education or healthcare system are accountable to these attrition rates.

Practicing Physicians

As mentioned previously, the term practicing physician is used by the AAMC (2019a) to describe physicians who have completed residency and are able to practice independently. Practicing physicians encompass two groups, fellows and attendings. Attendings are independently practicing physicians in their specialty. Fellows are physicians who have completed residency and are practicing under an attending and receiving additional training in their specialty. There are a variety of fellowship opportunities available following residency, but not all physicians choose to do a fellowship; this depends on the area of interest for the physician and what skills they are hoping to bring into their practice. According to the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), 10,433 positions for fellowships were given out of 12,925 applicants in 2021 (NRMP, 2021b).

According to the 2019 report by the AAMC (2019a), there were 936,254 practicing physicians in the U.S. Additionally, the breakdown by race/ethnicity for practicing physicians includes: 0.3% American Indian/Alaskan Native, 17.15% Asian, 5% Black/African American, 5.8% Hispanic/Latinx/or Spanish Origin, 0.8% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 1% multiple races, 56% White non-Hispanic, and 13.7% Unknown. The data for practicing physicians are particularly ambiguous because there is a significant amount of missing information regarding race/ethnicity (i.e., 13.7% did not report this identifier). Women currently (2019) only make up 36.3% of practicing physicians across specialty and career stage; this has been steadily on the rise since 2007 (AAMC, 2019b). This is still a far cry from parity with the U.S. general population. There is even less information about the percentage of physicians from historically marginalized sexual and gender social locations that practice in the U.S. There is progress being made in recording this information at the medical school level, but no known national data are available for the percentage practicing physicians in relation to inclusive sexual and gender social locations.

As mentioned previously, it is projected that the U.S. will experience a physician shortage between 17,800 and 77,100 by the year 2034 (AAMC, 2021a, b, c). As with all systemic problems, there are several factors that play into these estimates. First is the increase in the aging population, making the need for more physicians greater. There are many physicians moving toward retirement with not enough physicians-in-training to take their places. It is estimated that these shortages will likely impact lower income or rural areas who already have lower access to care (Boyle, 2020). To compound the issue of physician shortages, the attrition rates of women and underrepresented racial/ethnic physicians are important to consider. Compared to their men-identifying counterparts, six years after completing residency: 3.6% of men physicians are not working full time compared to 22.6% of women who are physicians. This number jumps if the physician has children to 4.6% for men and 30.6% for women. Contributing factors to this exodus include gender harassment, salary inequity, gender bias, and work life balance. (AAMC, 2019b; Kang & Kaplan, 2019).

If a physician wants to leave medicine for a period and return years later, (e.g., raising children) fees and additional training are often associated with returning to medicine (ranging in cost from $7,000 to $20,000; Paturel, 2019). Attrition rates with historically marginalized racial/ethnic physicians and sexual and gender diverse physicians is absent in the research. However, physicians from historically marginalized or systemically oppressed social locations may experience unique barriers in medicine, including being excluded from advancement opportunities, experiencing microaggressions, being held to a higher standard or differential treatment, and suffering from psychological burden or distress (Serafini et al., 2020). Even without the data on attrition rates, it is clear that there are many systemic barriers that obstruct success for historically marginalized physicians.

Conceptual Model for Systemic Change

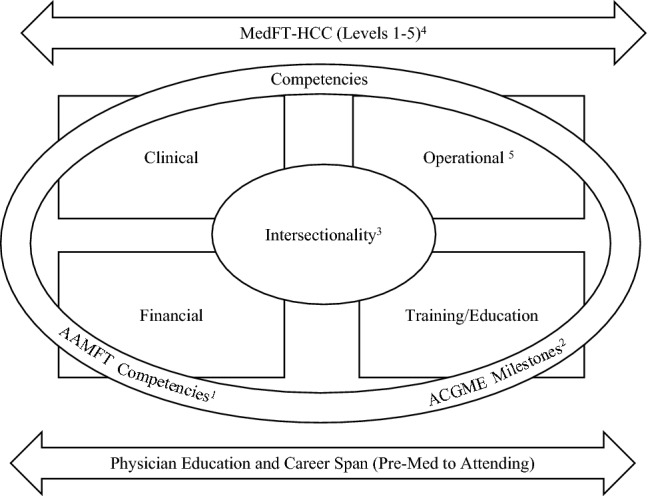

As with all systemic issues, a multilayered vision is needed to attend to recruitment and retention of a diverse population of physicians. This vision requires an understanding of the complex interweaving of various healthcare disciplines or specialties, levels of training, and historical experiences associated with marginalization and lack of representation across a physician’s career. Through the advanced skills that MedFTs have acquired (i.e., level 4 or 5 of the MedFT-HCC), particularly in roles that engage directly with medical students, residents, and practicing physicians, MedFTs are able to co-construct and implement ways to help enhance recruitment and retention among physicians from marginalized groups. The following segment describes a conceptual model (see Fig. 1) for MedFTs to consider when working in healthcare settings or when charged with addressing systemic changes needed to increase recruitment and retention of a diverse physician population at each stage of development (Hodgson et al., 2018).

Fig. 1.

The MedFTs’ Role in the Recruitment and Retention of a Diverse Physician Population. Note: 1AAMFT, 2018; 2ACGME, 2021; 3Crenshaw, 1989; 4Hodgson et al., 2018; 5Peeks, 2008

Prior to engaging with the stage of physician’s career, the MedFT must first identify their own identity in the model by discerning where they fit on the MedFT-HCC continuum (as seen across the top of Fig. 1). Recognizing their identity will assist the MedFT in determining their potential role(s) and align with others’ perceived vision for the MedFTs’ position in the system. This identity may also influence the MedFTs’ skills and role in relation to recruitment and retention of physicians across their training and career spans (Hodgson et al., 2018).

Second, the MedFT must identify the potential learners they may engage with via the physician education career span (as seen at the bottom of Fig. 1). The particular position on the MedFT-HCC and physician education career span indicate time and education level of both the MedFT and student/resident/practicing physician (ACGME, 2021; Hodgson et al., 2018). Understanding the time and educational expectations of each professional is essential to navigating systemic and sustainable changes in diversity and inclusion that best aligns to the developmental level of all involved.

Next, located in the background of the model are four squares representing the grounding theory (i.e., systemic change in health care) and framework (i.e., the Four World View). It is through systemic thinking and the four world view that the MedFT and medical learners can remain informed about the ways in which clinical, operational, financial, and education realms of health care are considered and sustained in context of one another. The interconnectedness of these four worlds offers a way to maintain a viable healthcare system, including successful retention of physicians.

The outer circle of the conceptual model represents competencies related to physician’s education and growth (i.e., the ACGME Milestones; ACGME, 2021) and the advancement and ethical responsibility of the MedFT (Competencies of Family Therapists in Healthcare Settings; Hodgson et al., 2018). MedFTs must maintain and strengthen their own competencies as outlined in the Competencies of Family Therapists in Healthcare Settings, while simultaneously being aware of the competencies of physicians in education and practice (AAMFT, 2018; ACGME, 2021). Accountability to these competencies ensures that both MedFTs and physicians across the career span recognize their duties to patients, co-providers, the healthcare system, and to accrediting bodies.

Finally, central to the model is intersectionality. As MedFTs push the needle forward on recruitment and retention of diverse physician populations, it is essential to keep in mind how multiple intersecting identities qualitatively change these individuals’ experiences (Crenshaw, 1989). MedFTs can attend to Domain 6 of the Competencies of Family Therapists in Healthcare Systems by practicing cultural humility and making ample room for historically marginalized groups to speak regarding their own experiences (AAMFT, 2018), while also recognizing the unique experiences that these individuals bring with them into their careers as physicians. It is the connection of these core concepts via this conceptual model that allows MedFTs to make systemic changes related to the recruitment and retention of a diverse physician population. Below are some specific ways that MedFTs can contribute to recruitment and retention in context of the conceptual model described above.

MedFTs as Advocates for Change

As with any systemic issue, the role of a MedFT is to appropriately intervene and engage with each component of the system while recognizing the ways in which those components interact with one another. Having awareness that there is a lack of representation among physicians and that systemic barriers to equity and diversity exist in the infrastructure of a healthcare system are not enough. MedFTs must serve as advocates for change and activate their collaborative skills into actionable ways that can enhance diversity, equity, inclusion, recruitment, and retention through their interface with all four worlds (Peek, 2008).

Systemic oppression of marginalized groups is and has been pervasive in the healthcare system and all systems in the U.S. It is essential to push for increased diversity, equity, and inclusion in every system since they were all historically and systematically structured to be inequitable (i.e., benefit some groups while hurting others). In order for MedFTs to best advocate for systemic change, they need to build relationships with the key stakeholders in all four worlds and implore them to become aware of and involved in the ways in which the worlds outside of their scope shape recruitment and retention in health care.

Clinical World

The clinical world offers an important window into change related to DEI for both patients and physicians. As patients engage in health care, they are looking for a microcosm of their larger community (i.e., representation similar to that in their community). After all, representativeness between physician and patient (i.e., social concordance; Johnson Thornton et al., 2011; Kurek et al., 2016) has positive outcomes on patient wellness. Patients’ quality of care is hinged upon culturally aware discussions in the room with their physician while also feeling a sense of safety and belonging when physicians care about their life and recognize how to adapt to their needs.

Furthermore, medical students and residents should be seeing this representation in their faculty/attendings who are training them, while also learning about equitable care throughout their medical practice with respect for race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, ability, etc. The representativeness of faculty has shown to increase positive outcomes for students and residents from historically marginalized learners (Oladeji et al., 2018). It is also important to attune to unethical practices of recruitment solely based on race or another marginalized identity (i.e., discriminatory interviewing or matching) to improve demographics on paper without a systemic effort to address diversity, equity, and inclusion of the system.

The clinical world should allow physicians at all levels to flourish in attending to the ways in which intersectionality influences their discussions with and about patient care and be given the opportunity to create and implement best practices when it comes to addressing the unique needs of patients via their intersectional identities, personal experiences, and priorities (Boatright et al., 2021; Kang & Kaplan, 2019). There are multiple ways that MedFTs can influence diversity, equity, and inclusion in their clinical work. This includes incorporating cultural humility into their own practice and supporting physician colleagues through joining rounds, patient encounters, case discussions, and other areas to emphasize relevant issues related to DEI.

Operational World

Operationally, equity and diversity must be addressed across many levels of the healthcare system, particularly through advertising, hiring, salary, and promotion policies and procedures. As a starting point, MedFTs should evaluate the websites, marketing materials, and advertisements for programs or work environments. What demographics and languages are visible or audible from websites? What activities are students or physicians engaged in through marketing materials, how are the benefits of those activities described in relation to the participants, rather than the benefit to the university or workplace? In advertisements for positions, how is DEI presented to readers?

As part of recruitment sessions, MedFTs should encourage students, residents, or practicing physicians to review student or employee handbooks. Offering a way to do a quick content analysis on key words in the handbook that matter to applicants may help in calling attention to family support resources, family leave practices, insurance coverage, procedures for evaluation, financial benefits provided, and priorities for the school or workplace. Having an eye on policies and procedures through a DEI lens helps to identify protocols that have sustained any inequities in the system. Then, it is essential to use one’s sphere of influence to advocate for equity and accountability in that healthcare system as they emerge.

Depending on the role of the MedFT, there are sometimes opportunities to influence equity in recruitment of other behavioral health staff or interns, or in residency match for clinics set in residency training programs. Even if the MedFT does not make final hiring, salary, or promotion decisions, their influence on the system is essential to systemic change. In many instances, a starting point is taking accountability at an institutional level for the contribution that the healthcare system has played in the perpetuation of systemic inequities in health care (Boatright et al., 2021; Kang & Kaplan, 2019). These inequities can be described in faculty or program meetings, via an educational lens through grand rounds, and/or in meetings with leaders who are charged with policy implementation.

MedFTs can also familiarize themselves with the key stakeholders in their healthcare system. Knowing who has the influence to make systemic change is important in order to influence change. Lack of access to leaders and absence of transparency in how policies are changed or implemented are indicators that DEI is not a priority for the system. MedFTs can look for DEI initiatives already occurring in a system and become involved in DEI committees. The fight for DEI in health care is essential for the well-being of all involved, meaning we all stand to gain from greater DEI in health care. A sign of concern is when DEI initiatives are only directed to students, residents, or physicians of color or from gender and sexually marginalized communities. The invisible labor in the lives of marginalized and systemically oppressed persons, while often spent on important work such as mentoring students and peers who share their social location(s), can result in even longer workdays and emotional distress for these individuals. Nominating predominately or exclusively physicians from historically marginalized social locations onto DEI related committees or initiatives maintains the inequity in work distribution and ensures that those who are not from systemically privileged communities resume their positions of not-knowing. In these instances, MedFTs must identify other champions of diversity, equity, and inclusion within or outside of their institution to find appropriate ways to advocate for change.

Financial World

Financially, MedFTs can push for incorporating funds related to equity and diversity into the budget. MedFT leaders must understand that funding alone will not address recruitment and retention challenges but use of finances is an essential component of systemic change. Boatright and colleagues (2021) recommend 3% of a healthcare system’s budget be devoted to diversity training (e.g., implicit bias in promotion processes, diversity and equity initiatives, and health equity in the community) or programming to support students, residents, practicing physicians (e.g., scholarships, providing employee assistance programs, including benefits like childcare or mental health services, and promoting wage equality). Deep reviews of salaries for all members in the healthcare system are likely needed, particularly as providers from historically marginalized social locations are typically paid less for the same job as their majority counterparts or held to different standards upon review. Finances can also be used to cultivate or retain diverse talent via scholarships, outreach to high school and college students, summer programs, or professional development sabbaticals (Kang & Kaplan, 2019).

The financial world may also include attending to the workplace needs of students, residents, and physicians while on site. For example, a financial model should be established to support a DEI work environment, including lactation space available for new mothers and bathrooms accessible for transwomen and transmen physicians. Furthermore, translation services are likely needed, alongside a review of physical accessibility into the building and throughout the building to support diverse abilities. Other financial investments in DEI may include on-site childcare and accessibility to health or exercise programs. MedFTs’ systemic training provides a platform to discuss biological, psychological, and social needs with financial officers, particularly by offering ways that can help promote retention and physician quality of life.

Training and Education World

The fourth world of training and education has been embedded in some way throughout each of the three worlds above, because it is essential to the sustainability of a system. Above all, a MedFT must devote themselves to their own education on diversity, equity, and inclusion (Domain 6, Competencies for Family Therapists in Healthcare Settings; Hodgson et al., 2018). They are likely unable to affect change in a system if they have not done their own work through cultural humility to recognize how they have endured or propelled inequity and injustice in their own lives and spheres of influence.

While training and education can take place in many formal and informal ways, it is important to keep in mind that (a) the development and implementation of DEI-related educational components must be a genuine reflection of the views of the instructor, healthcare team, and healthcare system as a whole, both words and in action, and (b) recognize that the commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion must be ongoing and involve all worlds of health care (i.e., clinical, operational, financial, and training/education).

Through the education world, MedFTs can return to Fig. 1 and determine where they are at in their development. Then, consider the level of development of others in the system, based on the education or career trajectory (e.g., medical student versus practicing physician). Upon situating themselves and others in levels of development, MedFTs can challenge themselves by finding the DEI practices that are represented in each of the four worlds. Finding these examples will help the MedFT to identify the strengths and areas of growth within each of the worlds. Furthermore, MedFTs can begin to learn about the ways in which social locations are supported or excluded in each of the four worlds. This assessment can offer a systemic lens for the ways in which the school or workplace contexts may be compromised due to neglect of intersectionality or of a particular world. Training opportunities can be developed based on these chasms. Ongoing evaluation of what is working in the system and areas that need attention are essential to the promotion of DEI. Once reflection, assessment, or evaluation ends, so does the likelihood that the MedFT or healthcare system is attending to DEI or medical student, resident, or practicing physician retention. Continued evaluation and consideration of DEI is of utmost importance to both the MedFT and healthcare system.

Conclusion

In order to address inequity in the healthcare system, specifically related to the recruitment and retention of diverse provider populations, MedFTs must engage at each level of the system as defined by Peek (2008), while also intervening through their different positions and spheres of influence they hold. As with any system, when we engage all of the parts, change is greater and more likely to be sustained (Bertalanffy, 1968). As MedFTs continue to grow and expand their influence in health care, they must be grounded in theory, recognize the competencies for their colleagues and themselves, and uphold the role of DEI and intersectionality in creating a more equitable healthcare system.

Funding

Funding was provided by East Carolina University Office of Equity and Diversity.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Corin E. Davis, Email: daviscor19@students.ecu.edu

Angela L. Lamson, Email: lamsona@ecu.edu

Kristin Z. Black, Email: blackkr19@ecu.edu

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. (2021). ACGME milestones.https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/accreditation/milestones/overview/. Accessed 24 June 2021

- American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy. (2018). Competencies for family therapists working in healthcare settings.www.aamft.org/healthcare. Accessed 24 June 2021

- American Medical Association (AMA). (2018). AMA adopts new policies at 2018 annual meeting. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-adopts-new-policies-2018-annual-meeting. Accessed 24 June 2021

- American Society of Hematology (ASH). (2020). U.S. medical schools push to recruit more LGBTQ students.https://www.ashclinicalnews.org/online-exclusives/u-s-medical-schools-push-recruit-lgbtq-students/. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). (2018). Graduation rates and attrition of U.S. medical students. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/reports/1/graduationratesandattritionratesofu.s.medicalstudents.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). (2019a). Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. https://www.aamc.org/datareports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). (2019b). The state of women in academic medicine: Exploring pathways to equity. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2018-2019-state-women-academic-medicine-exploring-pathways-equity. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) (2020). Report on residents: Executive Summary. https://www.aamc.org/media/50286/download?attachment

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). (2021a). 2020 facts: Applicants and matriculates.https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/interactive-data/2020-facts-applicants-and-matriculants-data. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). (2021b). AAMC report reinforces mounting physician shortage.https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/aamc-report-reinforces-mounting-physician-shortage. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). (2021c). Report on residents [Annual Report].https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/report/report-residents. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Bertalanffy LV. General systems theory as integrating factor in contemporary science. Akten des XIV. Internationalen Kongresses Für Philosophie. 1968;2:335–340. doi: 10.5840/wcp1419682120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright D, Berg D, Genao I. A roadmap for diversity in medicine during the age of COVID-19 and George Floyd. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2021;36:1089–1091. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06430-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P. U.S. physician shortage growing. Association of American Medical Schools; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989;199:139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw KW. On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Garces LM, Mickey-Pabello D. Racial diversity in the medical profession: The impact of affirmative action bans on underrepresented student of color matriculation in medical schools. The Journal of Higher Education. 2015;86(2):264–294. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2015.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooch, K. (2020). Average resident salary by specialty. Becker’s Hospital Review. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/compensation-issues/average-resident-salary-by-specialty.html. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Hanson, M. (2021). Average cost of college & tuition.https://educationdata.org/average-cost-of-college. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Hodgson, J., Trump, L., Wilson, G., & Garcia-Huidobro D. (2018). Medical Family Therapy in Family Medicine. In T. Mendenhall, A. Lamson, J. Hodgson, M. Baird (Eds.), Clinical Methods in Medical Family Therapy. Focused Issues in Family Therapy. Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-319-68834-3_2

- Hughes TM, Merath K, Chen Q, Sun S, Palmer E, Idrees JJ, Okunrintemi V, Squires M, Beal EW, Pawlik TM. Association of shared decision-making on patient-reported health outcomes and healthcare utilization. The American Journal of Surgery. 2018;216:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Thornton RL, Powe NR, Roter D, Cooper LA. Patient-physician social concordance, medical visit communication, and patients’ perceptions of health care quality. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;85:e201–e208. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J. M. (2021). LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. Gallup News. https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Kang SK, Kaplan S. Working toward gender diversity and inclusion in medicine: Myths and solutions. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):579–586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan. (N.D.). What is the real cost of medical school? https://www.kaptest.com/study/mcat/whats-the-real-cost-of-medical-school/. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Kaushik D. Medical burnout: Breaking bad. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek K, Teevan BE, Zlateva I, Anderson DR. Patient-provider social concordance and health outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: A retrospective study from a large federally qualified health center in connecticut. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2016;3:217–224. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0130-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggott K. Here’s why LGBTQ physicians should self-identify. American Academy of Family Physicians; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lu DW, Hartman ND, Druck J, Mitzman J, Strout TD. Why residents quit: National rates of and reasons for attrition among emergency medicine physicians in training. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2019;20(2):351–356. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2018.11.40449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SH, Doherty WJ, Hepworth J. Medical family therapy and integrated care. 2. American Psychological Association Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SH, Hepworth J, Doherty WJ. Medical family therapy: A biopsychosocial approach to families with health problems. Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). (2021a). Main residency match data and reports.https://www.nrmp.org/main-residency-match-data/. Accessed 24 June 2021

- National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). (2021b). Press release: NRMP 2021 fellowship results and report.https://www.nrmp.org/nrmp-sms-report-2021-appointment-year/. Accessed 24 June 2021

- Oladeji LO, Ponce BA, Worley JR, Keeney JA. Mentorship in orthopedics: A national survey of orthopedic surgery residents. Journal of Surgical Education. 2018;75(6):1606–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paturel A. Why women leave medicine. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Peek CJ. Planning care in the clinical, operational, and financial worlds. In: Kessler R, Stafford D, editors. Collaborative medicine case studies. Springer; 2008. pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Philibert I, Chang B, Flynn T, Friedmann P, Minter R, Scher E, Williams WT. The 2003 common duty hour limits: Process, outcome, and lessons learned. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2009;1(2):334–337. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00076.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postsecondary National Policy Institute (PNPI). (2021). First-generation students in higher education.https://pnpi.org/first-generation-students/. Accessed 24 June 2021

- RTI International . First year experience, persistence, and attainment of first-generation college students. NASPA; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Serafini K, Coyer C, Brown Speights J, Donovan D, Guh J, Washington J, Ainsworth C. Racism as experienced by physicians of color in the health care setting. Family Medicine. 2020;52(4):282–287. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2020.384384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Resident population and net change. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US#

- University of St. Augustine. (2021). Diversity in healthcare and the importance of representation. https://www.usa.edu/blog/diversity-in-healthcare/. Accessed 24 June 2021

- White T. Discrimination fears remain for LGBT medical students, study finds. Stanford Medicine News Center; 2015. [Google Scholar]