Abstract

Mutations in the 5′ portion of Xenopus U3 snoRNA were tested for function in oocytes. The results revealed a new cleavage site (A0) in the 3′ region of vertebrate external transcribed spacer sequences. In addition, U3 mutagenesis uncoupled cleavage at sites 1 and 2, flanking the 5′ and 3′ ends of 18S rRNA, and generated novel intermediates: 19S and 18.5S pre-rRNAs. Furthermore, specific nucleotides in Xenopus U3 snoRNA that are required for cleavages in pre-rRNA were identified: box A is essential for site A0 cleavage, the GAC-box A′ region is necessary for site 1 cleavage, and the 3′ end of box A′ and flanking nucleotides are required for site 2 cleavage. Differences between metazoan and yeast U3 snoRNA-mediated rRNA processing are enumerated. The data support a model where metazoan U3 snoRNA acts as a bridge to draw together the 5′ and 3′ ends of the 18S rRNA coding region within pre-rRNA to coordinate their cleavage.

18S, 5.8S, and 25-28S rRNAs are transcribed in the nucleolus of the eukaryotic cell by RNA polymerase I in a form of long precursor rRNA (pre-rRNA) that subsequently undergoes a number of processing cleavages to remove the external transcribed spacer sequences (ETS) and internal transcribed spacer sequences (ITS) and release the mature rRNAs. rRNA processing involves a number of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs). U3 and U14 snoRNAs have been implicated in processing steps leading to 18S rRNA formation in both lower (U3 [20] and U14 [31, 32]) and higher (U3 [7, 24, 43] and U14 [27]) eukaryotes. In addition, 18S rRNA formation in vertebrates requires U22 (49), U17(E1), E2, and E3 snoRNAs (35), and in yeast it requires snR10 (48) and snR30 (36) snoRNAs. The role of snoRNAs in rRNA processing is distinct from the function of the majority of snoRNAs that serve as guide RNAs for rRNA modification (2′-O-ribose methylation and pseudouridine formation). In this paper, we investigate the role of U3 snoRNA in rRNA processing to form 18S rRNA.

U3 is the most abundant snoRNA in the cell and is essential for viability, as tested in yeast (20, 42). Vertebrate U3 snoRNA appears to determine the order of cleavage events leading to 18S rRNA formation (7). In Xenopus laevis, U3 snoRNA is required for cleavage at site 1 (5′ end of 18S rRNA), site 2 (3′ end of 18S rRNA), and site 3 (5′ end of 5.8S RNA) (7, 43). In addition, U3 together with U14, U17(E1), and E3 snoRNAs are needed for cleavage near the 5′ end of the ETS in many eukaryotes (12, 24). In yeast, U3 snoRNA is needed for cleavage at site A0 (near the 3′ end of the ETS), site A1 (5′ end of 18S rRNA), and site A2 (within the ITS1) (20).

What is the mechanism by which U3 snoRNA mediates these cleavages in pre-rRNA? It has been proposed that the single-stranded 5′ hinge (4) and 3′ hinge (8), which separate domains I and II of U3 snoRNA, base pair with the ETS, thus docking U3 snoRNA on the pre-rRNA substrate. These base-pairing interactions are supported by phylogenetic comparisons (8), and compensatory base changes validate the U3 5′ hinge base pairing with the ETS of pre-rRNA in yeast (5). Once U3 snoRNA has docked on the pre-rRNA, it may base pair with sequences within the 18S pre-rRNA. In doing so, U3 snoRNA could act as a chaperone to prevent premature pseudoknot formation in 18S rRNA (19), similar to comparable interactions that occur in cis in bacteria (11). In yeast, three evolutionarily conserved regions in domain I of U3 snoRNA, the GAC element, box A′, and box A (42), are complementary to sequences in 18S rRNA (19), and chemical modification supports the model that they base pair (34). Compensatory mutations validated the base pairing interaction between the 5′ portion of box A and 18S rRNA in yeast but did not confirm the interaction between the 3′ portion of box A and 18S rRNA (46). The interaction between box A′ and 18S rRNA has not yet been experimentally tested in any organism. Base pairing between the GAC element and 18S rRNA can be drawn for yeast but not for vertebrates, calling its role into question. Therefore, further investigation is needed to explore the roles of the GAC element, box A′, and box A in U3 snoRNA, and this is the focus of the present study.

In order to understand the mechanism for U3 snoRNA function in rRNA processing, we have created a systematic array of mutations in the 5′ portion of the molecule, including the evolutionarily conserved GAC element, box A′, and box A, and tested their effects in a functional assay. The results reported here have uncovered a new cleavage site in the 3′ region of the ETS of vertebrate pre-rRNA, homologous with site A0 in yeast. In addition, by mutagenesis of U3 snoRNA we have uncoupled cleavage at sites 1 and 2, which normally occur in unison. Furthermore, specific nucleotides in U3 snoRNA that are required for distinct cleavages in pre-rRNA were identified: box A is essential for site A0 cleavage, the GAC-box and A′ region is necessary for site 1 cleavage, and a few nucleotides at the 3′ end of box A′ are required for site 2 cleavage. Finally, based on these data, a new model is presented in which U3 snoRNA acts as a bridge to draw together the 5′ and 3′ ends of the 18S rRNA coding region within pre-rRNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotide injections for U3 snoRNA depletion and rRNA analysis.

For U3 snoRNA depletion, stage 5 and 6 Xenopus laevis oocytes were injected with an oligonucleotide complementary to residues 39 to 54 of U3 snoRNA and rRNA was in vivo labeled by injection of 32P-UTP as described earlier (7). Capped T7 RNA polymerase transcripts of wild-type or mutated U3 snoRNA were synthesized and injected into the depleted oocytes; subsequently, nuclear RNA was isolated as described previously (7). The RNA was electrophoresed on a denaturing 1.2% (wt/vol) agarose gel containing 6% (vol/vol) formaldehyde and electrotransferred onto a Nytran Plus membrane (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, N.H.) for exposure to X-ray film (7). In some cases, the rRNA was analyzed by Northern blottings after radioactive rRNA on the filters had decayed for several months; filters were checked for the absence of residual radioactivity by using a Fuji X phosphorimager and BAS 1000 MacBas software. Northern hybridization was carried out in 6× SSC–1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate–5× Denhardt's solution –20% polyethylene glycol 6000 (wt/vol)–50 μg of sheared salmon sperm DNA/ml–100 μg of E. coli tRNA (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml for 12 to 16 h at a temperature 5°C below the Tm of the hybrid and then washed as previously described (7) (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0).

Hybridization probes.

The following antisense oligonucleotides were used as specific probes against the X. laevis 5′ ETS pre-rRNA: ETS-1 (nucleotides [nt] 30 to 47), 5′-CGGTCCTTTTTTCGGGCG-3′; ETS-2 (nt 475 to 498), 5′-GGCCTACTCTCCTTTCTTTCCGTC-3′; ETS-3 (nt 518 to 538), 5′-GGGGAGGGGGGGGGGAGGCGG-3′; ETS-4 (nt 549 to 572), 5′-GGGGGCCCCGCCCGGCCTGCCGCT-3′; ETS-5 (nt 627 to 650), 5′-CGGGTCGGCGCCCTGAGGCGTCAC-3′; ETS/18S (nt 700 to 715), 5′-GTAGCCACCTTTCCCG-3′.

The following oligonucleotides were used as probes against X. laevis 18S rRNA: 18S-1 (nt 713 to 737), 5′-TGCTACTGGCAGGATCAACCAGGTA-3′; 18S-2 (nt 797 to 819), 5′-TGATTTAATGAGCCATTCGCAGT-3′.

The following oligonucleotides were used as probes against X. laevis ITS1: ITS1-1 (nt 2539 to 2559), 5′-TCCGGGTGAGGGGGGTCTCGT-3′; ITS1-2 (nt 2659 to 2682), 5′-GGGTTCCTCGTCGTCCCTTTCGGG-3′; ITS1-3 (nt 2862 to 2879), 5′-GGTCTTCGAACCGCCCGG-3′; ITS1-4 (nt 2959 to 2974), 5′-GGGTCCTGCGGCGGCG-3′; ITS1-5 (nt 2999 to 3023), 5′-CGCGGCCCGGGCGCCCCGGGCCGGC-3′; ITS1-6 (nt 3030 to 3048), 5′-CTACCGGTGCTGCCGCTGA-3′.

All probes listed above were complementary to the sequence of X. laevis pre-rRNA (2) and were 32P labeled as described before (7).

U3 snoRNA mutagenesis.

U3 snoRNA mutants were created by using the one-step PCR approach described previously (8), with the T7 promoter sequence at the 5′ end of the 5′ (sense) primer preceding 21 nt of U3 snoRNA sequence (mutated as shown in Fig. 1; the deletion primers were 21 nt long, and the insertion primers were 21 nt plus the length of the insertion). The U3 box A mutations were derived from a 5′ (sense) primer with T7 promoter preceding 40 nt of X. laevis U3 snoRNA sequence (22) with the substitutions shown in Fig. 1. The U3 mutant sub 8-28 is the same as the box A+ mutant, and the U3 mutant sub 17-28 is the same as the box A mutant of Lange et al. (28). All deoxyoligonucleotides for U3 snoRNA mutagenesis were obtained from Genosys Biotechnologies (The Woodlands, Tex.) or Life Technologies GIBCO BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.). Oligo 39-54 for U3 snoRNA depletion was from Life Technologies GIBCO BRL. The following PCR cycle was used in the mutagenesis procedure: 94°C for 7 min, followed by 5 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 48°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, and then 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 32 s, with the final extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCRs used the Amplitaq Gold PCR kit from Perkin-Elmer (Branchburg, N.J.) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

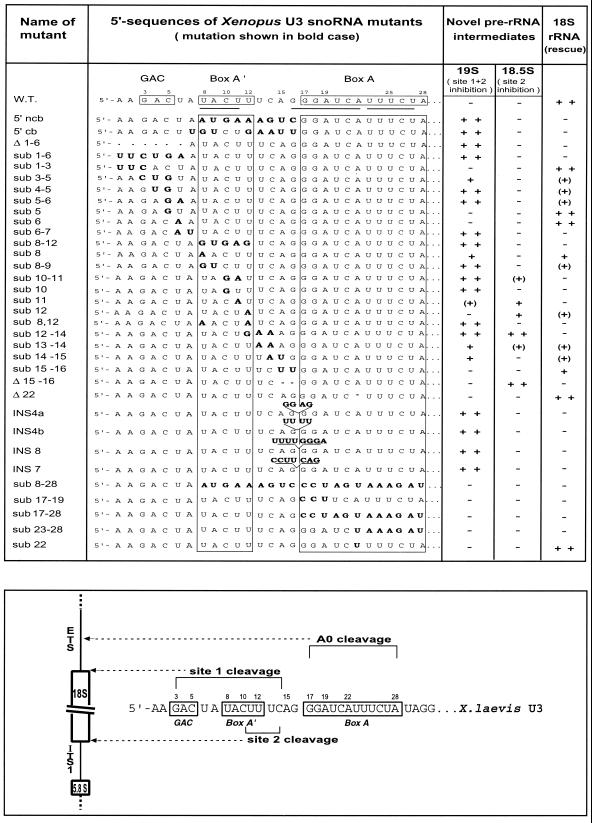

FIG. 1.

U3 snoRNA mutagenesis. (Top) Boldface letters indicate nucleotide substitutions or insertions. The amount of rRNA is shown: ++, much; +, some; (+), little; −, none. (Bottom) U3 nucleotides required for cleavage at site A0, 1, or 2 in pre-rRNA are bracketed.

snoRNA synthesis and purification.

The PCR products were gel purified and cloned into the pT7 Blue (R) T-cloning vector (Novagen, Madison, Wis.), and all mutations were confirmed by sequencing. DNA of the plasmid constructs served as the template in subsequent PCRs to produce templates for in vitro T7 RNA polymerase transcription (see reference 28 for details). The PCR templates were purified with a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The RNA concentration was estimated by comparison to reference samples with known concentrations on 8% (wt/vol) acrylamide–7 M urea gels electrophoresed in TBE (90 mM Tris-borate, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and stained with methylene blue. The concentration was confirmed by spectrophotometry (A260). The concentration of snoRNA used for oocyte injection in rescue experiments spanned a range of 0.125 to 1.5 ng/nl in order to find the optimum for rescue.

Primer extension.

Primer extension was performed as follows. The annealing mixture contained 3 μl of total RNA from 10 to 20 oocyte nuclei, 1 μl of 5× First Strand buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2), and 0.5 to 1 pmol of 32P-end-labeled primer. The primer was either the ETS/18S oligonucleotide used for Northern blottings or an 18S tag (5′ CGT CAC ACT CGA GGG CGA TCG 3′) complementary to nt 277 to 297 from the 5′ end of Xenopus 18S rRNA. The nucleotides in bold were substitutions in the tag sequence compared to the wild type, in order to distinguish nascent 18S rRNA from preexisting 18S rRNA. Samples were boiled for 5 min, slowly cooled for ∼30 min, and transferred to a 42°C water bath. Then, 30 μl was added, which contained 7 μl of 5× First Strand buffer, 2 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 2 μl of deoxynucleotide triphosphate mix (10 mM concentrations of each; Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.), 18.5 μl of H2O, and 100 to 200 U of SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The reaction mixture was incubated for 60 min and stopped by a chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Labeled products of the primer extension reaction were resolved on a 6% denaturing acrylamide gel next to a sequencing ladder prepared by dideoxy sequencing with the same end-labeled primer of a plasmid construct containing Xenopus pre-rRNA.

RESULTS

Mapping cis-acting elements in the GAC-box A′ region of U3 snoRNA.

The 5′ end of U3 snoRNA sequence has a high degree of phylogenetic conservation, containing the GAC element, box A′, and box A, listed in order from the 5′ end (42). In order to find out if these conserved regions of U3 snoRNA reflect areas of functional importance for rRNA processing, we created a series of U3 mutations (Fig. 1) and systematically tested them for the ability to promote mature 18S rRNA formation by an in vivo U3 depletion-rescue assay in Xenopus oocytes. In this assay, endogenous intact U3 snoRNA is destroyed by injection of an antisense oligonucleotide into Xenopus oocyte nuclei (7, 43). Subsequently, wild-type or mutant U3 snoRNA is injected together with 32P-UTP to analyze rRNA processing by gel electrophoresis. In the absence of U3 snoRNA disruption, the 40S rRNA precursor, processing intermediates, and the mature 18S and 28S rRNA species are seen (Fig. 2). After destruction of intact U3 snoRNA, 18S rRNA was not produced (Fig. 2), but its production was restored by injection of wild-type U3 snoRNA (Fig. 2). We investigated whether mutant U3 snoRNA could also restore 18S rRNA formation. The failure to make 18S rRNA was not due to instability of the injected U3 snoRNA mutant, because a 32P-labeled mutant carrying a large sequence substitution spanning boxes A′ and A remained stable for 2 h after oocyte injection (28). Also, this and other U3 transcripts mutated at the 5′ end were stable for 18 h after injection (data not shown). Moreover, the 5′ portion of U3 snoRNA is not essential for nucleolar localization of U3 snoRNA (28), indicating that all the mutations studied here can localize to the nucleolar compartment where pre-rRNA processing takes place.

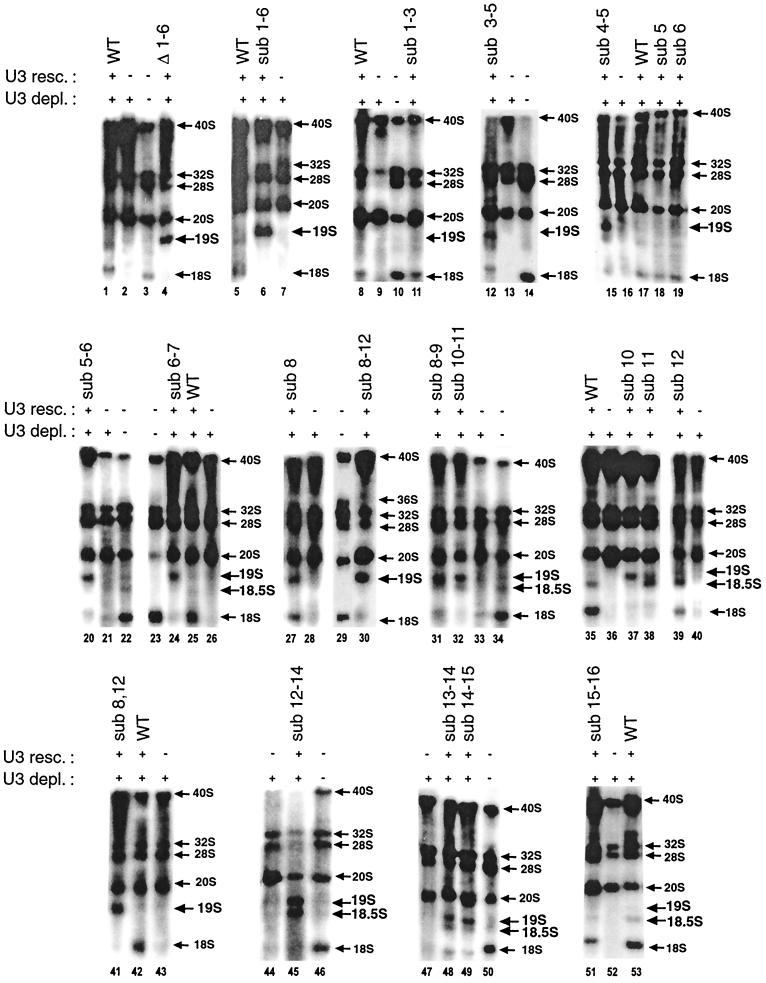

FIG. 2.

Mutations in the 5′ portion of Xenopus U3 snoRNA affect rRNA processing. Endogenous U3 snoRNA was not depleted (−) or was depleted (+) by injection into Xenopus oocytes of an antisense oligonucleotide complementary to nt 39 to 54. Subsequently, either wild-type (WT) or mutant (Fig. 1) synthetic U3 was injected into the oocytes for rescue. In vivo labeling was done by subsequent injection of 32P-UTP to trace changes in rRNA processing after U3 snoRNA depletion and rescue. The sizes of nuclear pre-rRNA and rRNA are indicated; note the novel 19S and 18.5S pre-rRNAs. Results of injection of additional U3 mutants not shown here are summarized in Fig. 1.

A series of mutations moving in from the 5′ end of U3 snoRNA (Fig. 1) were analyzed for their effect on rRNA processing. At the extreme 5′ end of the molecule, mutants with a deletion or substitution of nt 1 to 6 were unable to restore 18S rRNA formation (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 6, respectively). Instead, a novel pre-rRNA intermediate that was 19S in size was observed; the identity of the 19S pre-rRNA will be described below. The 5′ area of U3 snoRNA was subdivided for further analysis. Sequence substitution of U3 nt 1 to 3 did not compromise rRNA processing, and 18S rRNA production was restored (Fig. 2, lane 11). However, substitution of all three (sub 3-5) or just two (sub 4-5) out of three residues of the conserved GAC motif resulted in appearance of 19S pre-rRNA and weak to no production of 18S rRNA (Fig. 2, lanes 12 and 15, respectively). Surprisingly, the deleterious effect of U3 snoRNA mutagenesis of the GAC motif extended beyond it to nt 6 and 7 (U3 sub 5-6 or sub 6-7), and the novel 19S pre-rRNA was produced instead of 18S rRNA (Fig. 2, lanes 20 and 24, respectively). Thus, the nonconserved nucleotides between the evolutionarily conserved GAC motif and box A′ also are functionally important.

Next, we examined the importance of the box A′ region. Previously, we reported that U3 snoRNA with substitutions in the sequence of box A′ plus the flanking area (5′ cb and 5′ ncb mutants) formed 19S pre-rRNA instead of 18S rRNA (8). Both mutations encompass evolutionarily conserved box A′, suggesting that it might be essential for 18S formation. To check this possibility, we substituted the box A′ sequence (sub 8-12) in U3 snoRNA; this mutant failed to restore 18S rRNA formation to any significant extent and instead accumulated the 19S intermediate efficiently (Fig. 2, lane 30), just like the 5′ cb or 5′ ncb U3 mutants. In order to compare the relative importance of different residues within box A′, we split the box A′ mutation into 2-nucleotide and single-nucleotide substitutions. U3 snoRNA substituted at nt 8 and 9 or nt 10 and 11 inhibited 18S rRNA formation somewhat (sub 8-9) or completely (sub 10-11), respectively, and promoted accumulation of significant levels of the 19S intermediate (Fig. 2, lanes 31 and 32, respectively). Amazingly, just a single point mutation in box A′ of U3 snoRNA was able to prevent 18S rRNA production (sub 10 or sub 11; Fig. 2, lanes 37 and 38, respectively). Both of these mutants also caused accumulation of the novel 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 2, lanes 37 and 38). U3 snoRNA mutated in nt 11 also caused another novel intermediate, 18.5S pre-rRNA, to appear (Fig. 2, lane 38); the identity of 18.5S pre-rRNA will be described below. Since 18.5S pre-rRNA was barely seen after injection of the U3 sub 10-11 mutant (Fig. 2, lane 32), the appearance of 19S pre-rRNA after mutation of U3 nt 10 (Fig. 2, lane 37) seems to be dominant over 18.5S pre-rRNA that results from U3 mutated at nt 11 (Fig. 2, lane 38). Vertebrate U3 snoRNA has pseudouridines at nt 8 and 12 (14, 41), and point mutations at these positions were tested for function. In both cases, 18S rRNA was produced, but U3 sub 8 also accumulated 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 2, lane 27) and U3 sub 12 accumulated 18.5S pre-rRNA (Fig. 2, lane 39). A stronger deleterious effect was seen after injection of the double mutant (sub 8,12) which failed to restore 18S rRNA production and instead formed 19S pre-rRNA exclusively (Fig. 2, lane 41). Thus, just as was true for U3 sub 10-11 (see above), the appearance of 19S is dominant over 18.5S pre-rRNA. Other single-point mutations did not significantly impair 18S rRNA formation (Fig. 2, lanes 18 and 19, nt 5 or 6; nt 13, 14, 15, 16, or 22; data not shown).

Surprisingly, deleterious effects were also seen after injection of U3 snoRNA with mutations from the 3′ end of box A′ into the nonconserved nucleotides between box A′ and box A. Specifically, U3 sub 12-14 abolished 18S rRNA formation and both 19S and 18.5S pre-rRNA accumulated strongly (Fig. 2, lane 45). Similarly, mutations of U3 nt 13 and 14 or 14 and 15 greatly hindered 18S rRNA production; 19S pre-rRNA appeared after injection of both these U3 snoRNA mutants with some 18.5S pre-rRNA also appearing (Fig. 2, lanes 48 and 49, respectively). In contrast, mutation of U3 nt 15 and 16 was less deleterious and 18S rRNA was produced, although at a somewhat lower level (Fig. 2, lane 51).

All these observations suggest that 18.5S pre-rRNA accumulation results primarily from mutations that cluster around the 3′ boundary of box A′, spanning nt 11 to 13. Apparently, the residues at the 3′ boundary of box A′ are involved in an rRNA processing function distinct from the rest of the GAC-box A′ element, where mutation of nt 4 to 14 resulted in 19S pre-rRNA accumulation. Interestingly, 19S and/or 18.5S pre-rRNAs can sometimes be observed after rescue of 18S rRNA production by injection of wild-type U3 snoRNA (Fig. 2, lanes 1, 5, 35, and 53) or even occasionally in unperturbed oocytes (Fig. 2, lanes 22 and 34), suggesting that they might be transient precursors of 18S rRNA that usually are processed rapidly and, therefore, do not tend to accumulate under normal conditions.

Functional importance of box A of U3 snoRNA.

Mutation of U3 box A (sub 17-28) prevented production of 18S rRNA, and neither 19S nor 18.5S pre-rRNA appeared (Fig. 3A, lane 6). The same was also true for a U3 snoRNA mutation carrying a substitution at the 5′ end of box A (sub 17-19) or the 3′ end of box A (sub 23-28) where no 18S, 18.5S or 19S pre-rRNA accumulated (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 5, respectively), indicating that the left and right portions of U3 box A seem to have the same function. This is in contrast to box A′, where mutation of the right but not the left side produced 18.5S pre-rRNA. Nt 22 in the middle of box A is highly exposed (34), but its substitution (sub 22) or deletion (Δ 22) had no adverse effect on the function of box A (Fig. 1; data not shown). Box A had a more severe effect when mutated than was true for the GAC-box A′ element, since neither 19S nor 18.5S were formed. Moreover, mutations in U3 snoRNA spanning box A′ through box A (U3 sub 8-28) prevented formation of 18S, 18.5S, and 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 3A, lane 8), showing that the effects of box A mutation are dominant over those of box A′ and its 3′ flanking nucleotides where 19S and 18.5S pre-rRNAs were produced.

FIG. 3.

Effects on rRNA processing of substitutions in U3 box A (A), deletions (B), or insertions between box A′ and box A (C). Note that endogenous U3 snoRNA was not depleted in panel B, lanes 1 to 3. Other details are as described for Fig. 2. WT, wild type.

Spacing between box A and the 5′ end of U3 snoRNA is critical.

Mutations upstream of U3 box A caused 19S pre-rRNA to appear, but no 19S pre-rRNA was formed after mutation of U3 box A itself. Thus, nt 15 and 16 appear to be a boundary between different functional elements of the 5′ region of U3 snoRNA. We tested whether the spacing between U3 box A and the GAC-box A′ element was important for function in rRNA processing. Deletion of nt 15 and 16 in U3 snoRNA inhibited the formation of 18S rRNA, and 18.5S pre-rRNA appeared instead (Fig. 3B, lane 2). This differs from substitution of the same 2 nt in U3 (sub 15-16), where some 18S rRNA was made and 18.5S was absent (Fig. 3B, lane 4). In contrast, deletion of U3 nt 1 to 6 yielded the same result as substitution of these nucleotides (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 7, respectively). Thus, a distinct spacing between box A and the GAC-box A′ region appears to be necessary for proper U3 snoRNA function in rRNA processing. This notion was further substantiated by examination of a series of insertions between nt 16 and nt 17 (directly at the left border of U3 box A). Insertions of 4, 7, or 8 nt at this position in U3 snoRNA prevented any significant formation of 18S rRNA and instead 19S pre-rRNA strongly accumulated (Fig. 3C, lanes 3 and 4, and data not shown). This result was independent of the sequence used for insertion, and two different sequences used for the 4-nt insertion yielded the same effect (Fig. 3C, lanes 3 and 4).

Interestingly, some mutations have a strong negative effect that is dominant over the wild-type molecule. For example, injection of Δ1-6 or Δ15-16 mutations of U3 snoRNA into oocytes not depleted of endogenous U3 inhibited production of 18S rRNA and 19S or 18.5S pre-rRNAs, respectively, were formed instead (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2).

Identification of 19S and 18.5S rRNA processing intermediates.

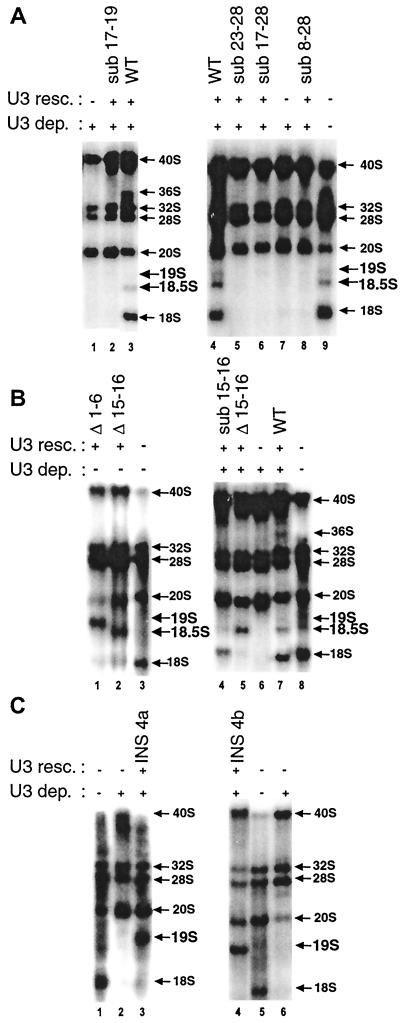

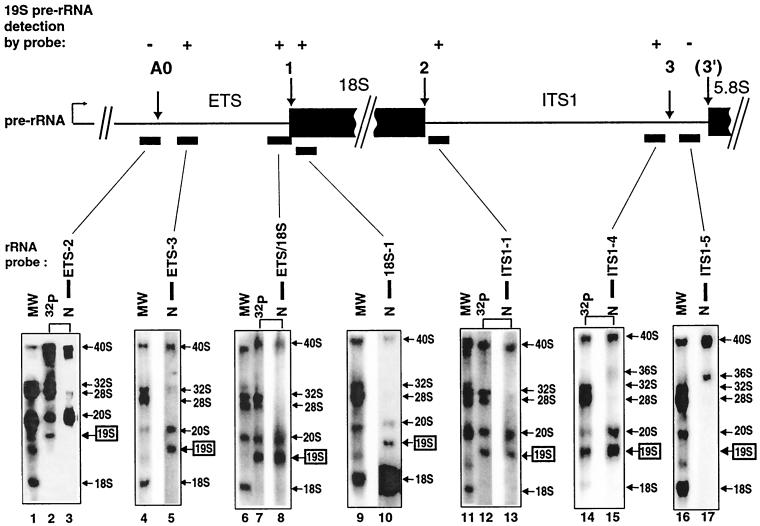

Northern blottings were performed with probes for several locations in pre-rRNA to identify 19S and 18.5S pre-rRNAs. RNA that was used for Northern blots (Fig. 4 and 5, lanes N) was compared to RNA from untreated oocytes that was 32P-labeled in vivo (Fig. 4 and 5, lanes MW) or RNA from U3-depleted oocytes injected with mutated U3 snoRNA to produce 18.5S pre-rRNA (Fig. 4) or 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 5). Both 18.5S and 19S pre-rRNA were detected on Northern blots with probes for the 18S coding region (Fig. 4, lane 11, and Fig. 5, lane 10, respectively), suggesting that these novel species are precursors to 18S rRNA. As expected, the 18S coding region probes also detected 18S rRNA as well as its 40S and 20S precursors in these Northern blots.

FIG. 4.

Identification of the novel 18.5S pre-rRNA by Northern blottings. Samples from in vivo labeling experiments (as described for Fig. 2) that showed strong accumulation of the novel 18.5S pre-rRNA (produced by rescue with Δ15-16 mutant U3) or 19S pre-rRNA (in lanes 6 and 8 and produced by rescue with Δ1-6 U3 mutant snoRNA) were resolved on denaturing agarose gels, electrotransferred onto Nytran Plus membranes, and exposed to X-ray film (lanes 32P). The filters were allowed to decay for up to 1 year and were hybridized with the radioactive probes shown by the bars under the map, derived from the ETS, 18S coding region, or ITS1. Lanes N, Northern blots of the 32P lane in the same panel after its radioactivity had decayed; the same lanes are linked by a bracket. Probes 18S-1 through ITS1-4 detected 18.5S pre-rRNA (+ above map of pre-rRNA). Lanes MW, in vivo-labeled pre-rRNA and rRNA from unperturbed oocytes as molecular weight markers.

FIG. 5.

Identification of the novel 19S pre-rRNA by Northern blottings. Samples from in vivo labeling experiments (as described for Fig. 2) that showed strong accumulation of the novel 19S pre-rRNA (produced by rescue with 5′ cb, 5′ ncb, or Δ1-6 U3 mutant snoRNA) were allowed to decay and hybridized with probes from the ETS, 18S coding region, or ITS1 (see Fig. 4 for details). Note that 19S pre-rRNA was detected by probes from ETS-3 to ITS1-4 (+ above map of pre-rRNA).

In order to map the boundaries of the 18.5S and 19S pre-rRNAs, Northern blottings were performed with probes for the ITS1 and the ETS. Most probes for the ITS1 detected 18.5S pre-rRNA (Fig. 4, lanes 5, 13, and 15) and 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 5, lanes 13 and 15) as well as 40S and 20S pre-rRNAs. However, probe ITS1-5, which is complementary to sequences near the 3′ end of the ITS1, failed to detect 18.5S pre-rRNA (Fig. 4, lane 17), 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 5, lane 17), or 20S pre-rRNA. As a positive internal control, this probe did detect 40S pre-rRNA as well as 36S pre-rRNA, which is known to contain all sequences in pre-rRNA except for the ETS and 18S coding region. Similar results were found for probe ITS1-6, which is even closer to the 3′ end of the ITS1 (data not shown).

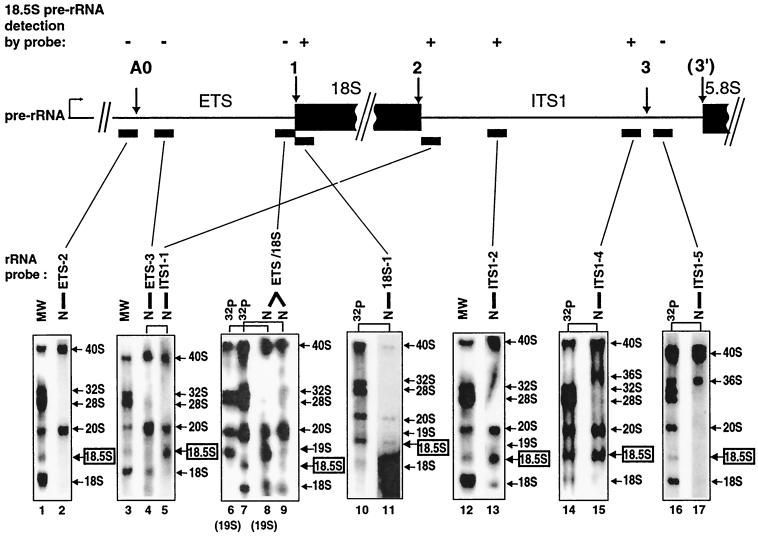

These results, summarized in Fig. 6, demonstrate that 18.5S, 19S, and 20S pre-rRNA all seem to share the same 3′ end, which is between 100 and 130 nt upstream of the 5′ end of 5.8S RNA. This refines the conclusions of others that cleavage site 3 is near but not at the very end of ITS1 in Xenopus pre-rRNA (40, 49). It is unknown if there is an endonucleolytic cleavage at site (3′) in metazoan pre-rRNA or if instead the 5′ end of metazoan 5.8S RNA is created by exonuclease trimming after cleavage within the ITS1, comparable to the situation in yeast (18). Normally in yeast the exonucleolytic trimming initiates at site A3, which requires 7-2/MRP snoRNA (9, 18, 33, 45), and is distinct from site A2, which is U3 snoRNA dependent (20) and resides slightly upstream of site A3. It remains to be determined if U3-dependent site 3 within the ITS1 of Xenopus pre-rRNA is a composite of the yeast A2 and A3 sites. Interestingly, sites A2 and A3 appear to be linked in yeast (3, 13, 51).

FIG. 6.

Summary of cleavages that produce 20S, 19S, and 18.5S pre-rRNA. Results of Northern blots shown in Fig. 4 and 5 and data not shown are summarized here. Xenopus 20S, 19S, and 18.5S pre-rRNA all share the same 3′ end (produced by cleavage at site 3 in the ITS1), but their 5′ ends vary as indicated. The 5′ end of 20S pre-rRNA is the same as the 5′ end of 40S pre-rRNA (26, 44). X indicates the inhibited cleavage sites, resulting in accumulation of 20S, 19S, or 18.5S pre-rRNAs. Cleavage sites in yeast pre-rRNA are indicated (reviewed in reference 52) for comparison to sites in vertebrate pre-rRNA.

Northern blottings showed that the 5′ ends were different for 18.5S, 19S, and 20S pre-rRNAs, in contrast to the identity of their 3′ ends. Probes for the ETS failed to detect 18.5S pre-rRNA (Fig. 4, lanes 2, 4, and 9), although 40S and 20S pre-rRNA were seen as expected in the Northern blots. These results suggest that the 5′ end of 18.5S pre-rRNA is formed by cleavage at site 1, which is at the 5′ end of the 18S coding region. Unlike the situation for 18.5S pre-rRNA, probes for the 3′ end of the ETS did detect 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 4, lane 8, and Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 8), as well as 40S and 20S pre-rRNA. However, probes complementary to sequences more upstream in the ETS, extending to its 5′ end, did not detect 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 5, lane 3), although 40S and 20S pre-rRNAs were visualized. These data suggest that 19S pre-rRNA results from cleavage at a site within the ETS, not described previously for metazoans, which we named site A0.

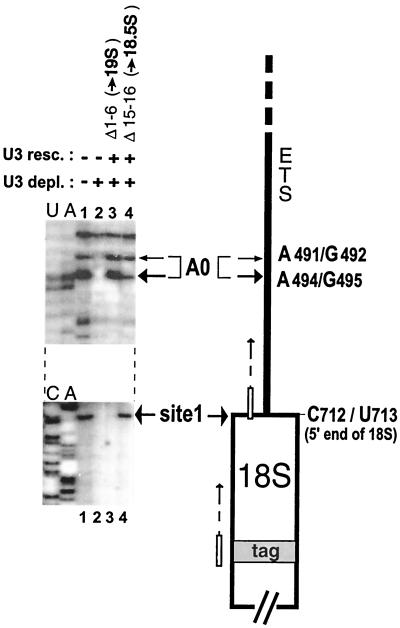

In order to extend these findings to the nucleotide level, primer extension of nascent pre-rRNA was used to analyze the 5′ ends of 19S and 18.5S pre-rRNAs. We used the oligonucleotide primer ETS/18S, complementary to the 3′ portion of the ETS sequence (Fig. 4 and 5), for extension to map the A0 cleavage site in Xenopus pre-rRNA at the nucleotide level. As can be seen in Fig. 7, the A0 site comprises two cleavages: A491-G492 and A494-G495. The ratio between the bands at these two positions varies between different oocyte preparations. We also found that reverse transcription is stopped at position A494-G495 in Xenopus liver cells (data not shown), indicating that cleavage at this site is common for different types of cells and is not restricted to oocytes. Cleavage at site A0 is U3 dependent, and bands at these positions are absent if U3 snoRNA is depleted (Fig. 7, lane 2). Strong bands were seen at the A0 cleavage site after treatment to produce 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 7, lane 3) but were also present at a lesser intensity after treatment to produce 18.5S pre-rRNA or even in nontreated oocytes (Fig. 7, lanes 4 and 1, respectively). This confirms the suggestion from Northern blots that cleavage at A0 probably occurs in normal rRNA processing (since, on occasion, some 19S pre-rRNA can be seen in nondepleted oocytes; Fig. 2, lanes 22 and 34), but subsequent cleavage at sites 1 and 2 flanking the 18S coding region likely occurs quite rapidly, thus preventing the accumulation of 19S pre-rRNA in unperturbed oocytes. The existence and the position of the 19S pre-rRNA 5′ terminus has been additionally confirmed by an RNase protection assay with a 32P-labeled antisense ETS RNA probe and by S1 nuclease analysis, respectively (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Mapping the novel A0 cleavage site in pre-rRNA by primer extension. RNA extracted from nuclei of unperturbed Xenopus oocytes (lane 1), oocytes depleted of endogenous U3 snoRNA (lane 2), or U3 depleted or rescued with U3 snoRNA mutants that promote strong accumulation of 19S pre-rRNA (lane 3) or 18.5S pre-rRNA (lane 4) was used as the template for primer extension; the 32P-labeled products of reverse transcription shown here next to sequencing lanes primed with the same primer were resolved on a 6% acrylamide denaturing gel. Site A0 cleavage was detected in pre-rRNA using a primer complementary to the 3′ end of the ETS (open box with arrow; same as ETS/18S probe in Fig. 4 to 6); site 1 cleavage was specifically detected in plasmid-expressing tag containing 18S rRNA using a primer complementary to the tag region near the 5′ end of 18S rRNA (open box with arrow).

Primer extension was also used to detect cleavage at site 1, which abuts the 5′ end of the 18S coding region. For this purpose, we used a primer complementary to a foreign tag sequence introduced in the 5′ portion of the 18S rRNA sequence in order to discriminate nascent 18S rRNA from the bulk of the preexisting mature 18S rRNA in the oocytes. In this case, a plasmid vector containing the entire pre-rRNA repeat unit with the 18S tag sequence substitution and driven by the RNA polymerase I promoter was expressed in oocyte nuclei. As can be seen in Fig. 7, cleavage at site 1 is seen in unperturbed oocytes (lane 1) but not in U3-depleted oocytes (lane 2), indicating that site 1 cleavage is U3 dependent. In confirmation of our Northern blot analysis (Fig. 4), cleavage at site 1 also occurred after treatment to produce 18.5S pre-rRNA (Fig. 7, lane 4) but was absent in 19S pre-rRNA (Fig. 7, lane 3).

Therefore, as summarized in Fig. 6, both the Northern blot and primer extension analyses indicate that 19S pre-rRNA results from an inhibition of cleavage at site 1 and site 2, in contrast to 18.5S pre-rRNA that is cleaved at site 1. However, cleavage at site A0 occurs efficiently in oocytes producing 19S or 18.5S pre-rRNAs (Fig. 7).

DISCUSSION

Regions in vertebrate U3 snoRNA needed to form 18S rRNA.

The conclusions from the dissection of Xenopus U3 snoRNA are summarized in Fig. 1. We found that nt 4 to 14 are required for site 1 cleavage of pre-rRNA, as their mutation obliterates this cleavage and 19S pre-rRNA accumulates. This is the first time in any organism that a function has been shown for the conserved GAC-box A′ element, which seems to be a functional continuum. Within this region, nt 11 to 13 appear to have an additional role, being important also for site 2 cleavage in pre-rRNA (18.5S pre-rRNA accumulates). This is the first time that site 2 cleavage has been uncoupled from site 1 cleavage by mutation of U3 snoRNA. Finally, our data show that Xenopus U3 box A is required for the newly discovered site A0 cleavage, and mutation of this area of U3 snoRNA blocks any further processing of 20S pre-rRNA, which is a precursor to 18S rRNA.

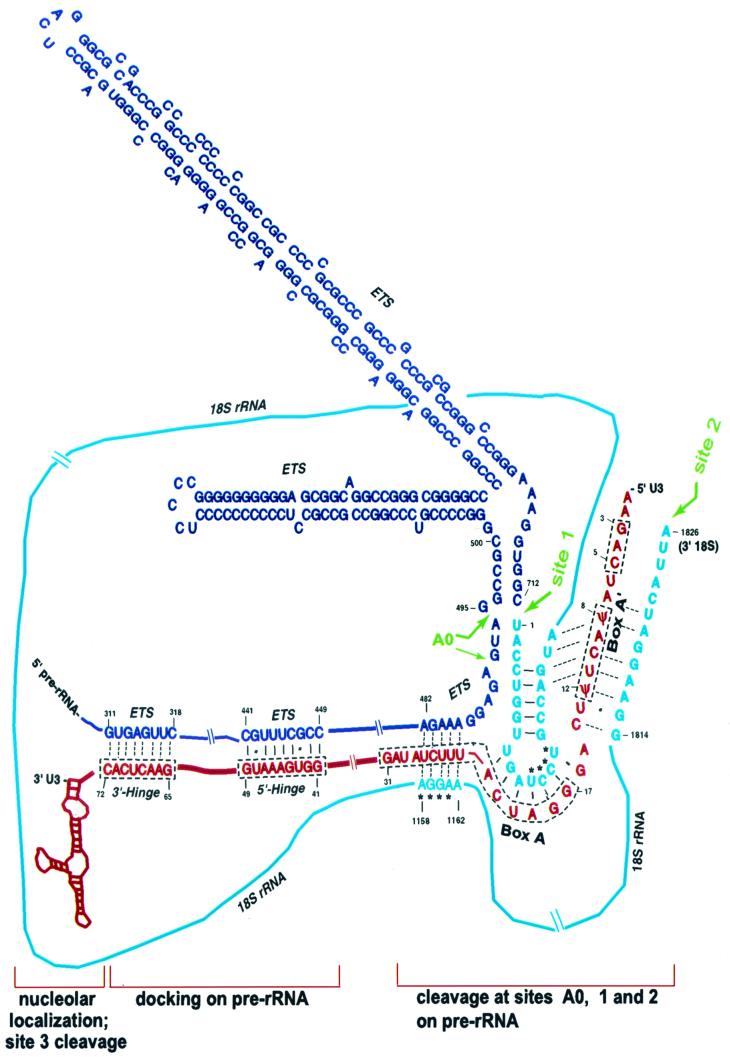

These data suggest a model for U3 snoRNA interaction with the pre-rRNA substrate to be processed (Fig. 8). First, U3 snoRNA is transported from the nucleoplasm to the nucleolus, its site of action for rRNA processing. Box D and box C (28) and/or box C′ (39) in domain II of U3 are required for nucleolar localization. Having arrived at its cellular destination, we propose that U3 snoRNA docks on the pre-rRNA substrate by base pairing between the two hinge regions of U3 with the ETS of pre-rRNA (8). Changes in spacing between the 5′ and 3′ hinges as well as between the hinge regions and boxes A′ and A of U3 snoRNA impair the function of U3 in rRNA processing for production of 18S rRNA, suggesting that these regions of U3 snoRNA interact with the pre-rRNA substrate at the same time (8). Similarly, as shown here (Fig. 3), changes in the spacing between box A′ and box A inhibit cleavage at site 1 or site 2, implying that these two regions of U3 snoRNA interact with the pre-rRNA substrate at the same time. Domain I of U3 has been hypothesized to base pair with sequences within the 18S rRNA coding region of pre-rRNA, acting as a chaperone (19). Our data suggest specific base-pairing interactions between U3 and the 18S rRNA coding region, as elaborated below.

FIG. 8.

Model for vertebrate U3 snoRNA interactions with pre-rRNA. The ETS of Xenopus pre-rRNA is drawn in dark blue and the 18S rRNA coding region in light blue; U3-dependent cleavage sites A0, 1, and 2 are in green. Xenopus U3 snoRNA is in red. Domain II of U3 is required for nucleolar localization (28) and for site 3 cleavage (7). The 5′ hinge and 3′ hinge of U3 snoRNA are proposed to dock U3 on pre-rRNA by base pairing with sequences in the ETS (8). Putative base-pairing interactions between the 5′ region of U3 snoRNA and sequences in the ETS and 18S coding region of pre-rRNA are indicated (see text). U3 snoRNA is proposed to act as a bridge to draw together cleavage sites A0, 1, and 2. Solid lines indicate base pairs between U3 snoRNA and pre-rRNA confirmed by compensatory base changes in yeast (5, 46), and dotted lines denote putative base pairs deduced by sequence complementarity and phylogenetic comparisons. Alternative base pairing interactions between U3 box A′ and the 5′ or 3′ end of the 18S coding region are shown. ∗, nucleotides in 18S rRNA that base pair to form the central pseudoknot (19). A computer-based (M-fold 3.0) model is shown for the ETS between sites A0 and 1, but bars for base pairing are not included. Pseudouridine (ψ) has been mapped to nt 8 and 12 of vertebrate U3 snoRNA (14, 41), though not studied directly in Xenopus.

U3-dependent cleavage at site A0.

We suggest that box A helps to position U3 snoRNA properly on pre-rRNA to allow U3-dependent cleavage at site A0 to occur. We found that when box A is mutated in Xenopus U3 snoRNA, there is inhibition of cleavage at site A0 and at sites 1 and 2 posited to occur later in the processing pathway. It has been hypothesized that the 3′ portion of box A base pairs with sequences in the 18S coding region (nucleotides 1158-AGGAA-1162 in Xenopus) to prevent pairing with nt 12 to 15 of 18S, thus blocking premature pseudoknot formation (19); the nucleotides that base pair to form the pseudoknot in mature 18S rRNA are indicated in Fig. 8. However, substitution of this AGGAA sequence in yeast 18S rRNA and the compensatory mutation in the complementary region in U3 box A did not restore 18S rRNA formation, thus calling into question the importance of its putative base pairing with U3 box A (46). As an alternative, we note that the same region of box A in U3 could pair with nucleotides 482-AGAAA-486 in the Xenopus ETS, preceding cleavage site A0 (Fig. 8). Moreover, mutation of these nucleotides in Xenopus U3 snoRNA (sub 23-28; Fig. 3) inhibits cleavage at site A0. Site A0 has not yet been mapped in most organisms, but in Trypanosoma brucei where its position is known (17), it is also 8 nt downstream from 5 nt in the ETS that have the potential to base pair with the same 3′ portion of U3 box A (data not shown; ETS sequence from D. Campbell and T. Hartshorne, personal communication).

The position of site A0 in Xenopus (218 or 221 nt upstream of site 1) is comparable to that reported for yeast (90 nt upstream of site A1 [20]) and trypanosomes (116 nt upstream of site A1 [17]). Moreover, site A0 appears to be within a base-paired stem where site 1 is directly opposite it (Fig. 8), similar to the secondary structure arrangement for yeast (21) and for trypanosomes (17). Therefore, cleavage site A0 in Xenopus is homologous to cleavage site A0 in yeast and trypanosomes. Despite the secondary structure, site A0 cleavage is not dependent on RNase III (25) as originally suggested (1).

Site A0 is different from another U3-dependent site found further upstream in the ETS of vertebrates (12, 24) which we name here site A′ (formerly site 0; 15). In trypanosome pre-rRNA, cleavage occurs both at site A′ and site A0 (17). Although cleavage is seen at site A′ in many metazoa as the initial event in rRNA processing (23), little to no cleavage is seen at this site in Xenopus oocytes (38, 44) nor has site A′ cleavage been observed in yeast (52).

Until now, site A0 has not been observed in metazoa. The discovery and characterization here of the novel 19S pre-rRNA in Xenopus suggests that its 5′ end results from cleavage at A0 but subsequent cleavage at sites 1 and 2 is inhibited (Fig. 7). These data suggest that, normally, cleavage at site A0 precedes cleavage at sites 1 and 2. A similar deduction has been made for yeast, where yeast 22S pre-rRNA (52) has the same composition as Xenopus 19S pre-rRNA, and is found when cleavage at sites A1 and A2 is inhibited. Cleavage at yeast site A0 can occur uncoupled from cleavage at sites A1 and A2 when box A of U3 snoRNA is mutated (19), when the U3-associated protein Mpp10p is truncated (29), or when the U3-associated helicase Dhr1p is depleted (10). Similarly, A0 cleavage is unaffected when cleavage at site A1 is inhibited by mutation near the 5′ end of 18S rRNA (46). These results suggest that cleavage at site A0 might occur slightly earlier than cleavages at sites A1 and A2, which follow rapidly.

U3-dependent cleavage at site 1 in pre-rRNA.

The 5′ end of box A has been proven by compensatory base changes to base pair with sequences near the 5′ end of 18S rRNA (46), located in the loop of a stem-loop structure shown to be a determinant of cleavage at site A1 in yeast (47, 53). This interaction between the 5′ end of U3 box A and 18S rRNA is universal and can also be drawn for higher organisms (19) (Fig. 8 for Xenopus); the base pairing favorably positions vertebrate U3 snoRNA close to the cleavage sites A0 and 1. Since mutation of Xenopus box A inhibits cleavage at site A0, the potential importance of the 5′ end of box A for site 1 cleavage, which is later in the processing pathway, was not revealed.

It remains to be determined if these cleavages in pre-rRNA are due to ribozyme activity of U3 or another snoRNA or are due to a protein-based enzyme, which might associate with or dock on U3 snoRNA. Candidates for the latter include the U3-associated proteins Mpp10p, Imp3p, Imp4p, (29, 30), and/or a member of the 3′-phosphate cyclase family (6), consistent with the report that in vitro cleavage at site 1 generates a 2′, 3′ phosphate at the 3′ end of the ETS (16, 55). RNA or protein trans-acting factors may modulate the RNA-RNA interactions essential for cleavage.

Role of U3 box A′ for cleavage at sites 1 and 2 in pre-rRNA.

We have shown here that residues in Xenopus U3 box A′ are required for cleavage at site 1 and at site 2 of pre-rRNA. As shown in Fig. 8, box A′ potentially base pairs with sequences near the 5′ end of the 18S coding region (19), juxtaposing it close to cleavage site 1. This potential interaction is evolutionarily conserved (19). We propose that subsequently U3 box A′ loses its pairing interaction with the 5′ end of 18S rRNA and instead it and adjacent nucleotides enter into new base pairing with sequences near the 3′ end of 18S rRNA in the pre-rRNA (Fig. 8). This would have the effect of drawing the 5′ and 3′ ends of 18S rRNA close together so that cleavage at these two sites could be coordinated. In essence, U3 snoRNA may act as a bridge between the two ends of 18S rRNA, as has been hypothesized previously that a snoRNA might replace the base-paired stem (37) that flanks 16S-18S rRNA in bacteria (54) and yeast. The bases involved in this putative interaction are evolutionarily conserved and identical in 18S rRNA and U3 snoRNA of all vertebrates. We have shown here that mutation of nt 11 to 13, which disrupts the putative base pairing with the 3′ end of 18S rRNA, inhibits cleavage at site 2 but not at site 1, giving rise to 18.5S pre-rRNA (Fig. 2). Presumably, in these cases, the 3′ end of 18S rRNA in the pre-rRNA cannot be drawn close to its 5′ end nor is it associated with U3 snoRNA, and site 2 cleavage fails to occur. It appears that cleavage at site 1 is a prerequisite for cleavage at site 2, since cleavage at site 2 has never been observed by anyone without cleavage at site 1.

Therefore, in the model proposed here, U3 snoRNA draws together cleavage sites A0, 1, and 2. Thus, U3 snoRNA is posited to act as a chaperone to fold the pre-rRNA properly by base pairing with it. Interestingly, putative base pairing between U3 snoRNA and pre-rRNA occurs near each of the cleavage sites (A0, 1, and 2). U3 snoRNA also would impart temporal order to the cleavages, with cleavage at A0 preceding site 1 which precedes site 2. When the 3′ end of U3 box A′ is mutated, it would fail to associate with the 3′ end of 18S rRNA, explaining the inhibition of cleavage at site 2. When the GAC-box A′ element of U3 is mutated, cleavage at sites 1 and 2 are inhibited (the sequence upstream of box A′, including GAC, does not have any obvious complementarity to pre-rRNA near sites 1 and 2 and instead might be a recognition element for a trans-acting factor). When U3 box A is mutated, cleavage at sites A0, 1, and 2 is inhibited.

Differences in rRNA processing between vertebrates and yeast.

While there are several similarities in rRNA processing between vertebrates and yeast, there are also significant differences. Unlike vertebrates, formation of the true 3′ end of yeast 18S rRNA (site D) seems to occur in the cytoplasm (50) and therefore appears to be independent of U3 snoRNA. However, at an earlier step in yeast rRNA processing, U3-dependent cleavage occurs somewhat downstream in the ITS1 at site A2 (Fig. 6). As discussed above, it remains unknown if Xenopus site 3′ is a composite of yeast sites A2 and A3.

There also appear to be differences in the functions of elements within U3 snoRNA for rRNA processing. Mutation within box A of yeast U3 snoRNA impairs cleavage at sites A1 and A2 but not at site A0 (19), in contrast to what we observed for the vertebrate, Xenopus, where box A mutation inhibits cleavage at site A0. In this context, it is interesting that the base pairing between the 3′ part of box A and the ETS near site A0 hypothesized here for Xenopus cannot be drawn for yeast. Also, the base pairing between the GAC element of U3 snoRNA and 18S rRNA hypothesized for yeast (19) cannot be drawn for Xenopus.

Future studies are needed to experimentally verify by compensatory base changes or cross-linking the interactions proposed here between U3 snoRNA and pre-rRNA, which may either be universally conserved or else specific just to lower or higher eukaryotes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Bertino for preparation of Xenopus 18S rRNA containing a tag and T. S. Lange for helpful comments about this paper.

This work was supported in part by NIH GM 61945.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abou Elela S, Igel H, Ares M., Jr RNase III cleaves eukaryotic preribosomal RNA at a U3 snoRNP-dependent site. Cell. 1996;85:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajuh P M, Heeney P A, Maden B E H. Xenopus borealis and Xenopus laevis 28S ribosomal DNA and the complete 40S ribosomal precursor RNA coding units of both species. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1991;245:65–71. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allmang C, Henry Y, Morrissey J P, Wood H, Petfalski E, Tollervey D. Processing of the yeast pre-rRNA at sites A2 and A3 is linked. RNA. 1996;2:63–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beltrame M, Tollervey D. Identification and functional analysis of two U3 binding sites on yeast pre-ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 1992;11:1531–1542. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltrame M, Tollervey D. Base pairing between U3 and the pre-ribosomal RNA is required for 18S rRNA synthesis. EMBO J. 1995;14:4350–4356. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billy E, Wegierski T, Nasr F, Filipowicz W. Rcl1p, the yeast protein similar to the RNA 3′-phosphate cyclase, associates with U3 snoRNP and is required for 18S rRNA biogenesis. EMBO J. 2000;19:2115–2126. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borovjagin A V, Gerbi S A. U3 small nucleolar RNA is essential for cleavage at sites 1, 2 and 3 in pre-rRNA and determines which rRNA processing pathway is taken in Xenopus oocytes. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:1347–1363. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borovjagin A V, Gerbi S A. The spacing between functional cis-elements of U3 snoRNA is critical for rRNA processing. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:57–74. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu S, Archer R H, Zengel J M, Lindahl L. The RNA of RNase MRP is required for normal processing of ribosomal RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:659–663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colley A, Beggs J D, Tollervey D, Lafontaine D L. Dhr1p, a putative DEAH-box RNA helicase, is associated with the box C+D snoRNP U3. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7238–7246. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7238-7246.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dennis P P, Russell A G, Moniz de Sá M. Formation of the 5′ end pseudoknot in small subunit ribosomal RNA: involvement of U3-like sequences. RNA. 1997;3:337–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enright C A, Maxwell E S, Eliceiri G L, Sollner-Webb B. ETS rRNA processing facilitated by four small RNAs: U14, E3, U17 and U3. RNA. 1996;2:1094–1099. . (Erratum, 2:1318). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eppens N A, Rensen S, Granneman S, Raué H A, Venema J. The roles of Rrp5p in the synthesis of yeast 18S and 5.8S rRNA can be functionally and physically separated. RNA. 1999;5:779–793. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganot P, Jády B E, Bortolin M-L, Darzacq X, Kiss T. Nucleolar factors direct the 2′-O-ribose methylation and pseudouridylation of U6 spliceosomal RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6906–6917. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerbi S A. Small nucleolar RNA. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;73:845–858. doi: 10.1139/o95-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannon G J, Maroney P A, Branch A, Benenfield B J, Robertson H D, Nilsen T. Accurate processing of human pre-rRNA in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4422–4431. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.10.4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartshorne T, Toyofuku W. Two 5′-ETS regions implicated in interactions with U3 snoRNA are required for small subunit rRNA maturation in Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3300–3309. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.16.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry Y, Wood H, Morrissey J P, Petfalski E, Kearsey S, Tollervey D D. The 5′ end of yeast 5.8S rRNA is generated by exonucleases from an upstream cleavage site. EMBO J. 1994;13:2452–2463. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes J M X. Functional base-pairing interaction between highly conserved elements of U3 small nucleolar RNA and the small ribosomal subunit RNA. J Mol Biol. 1996;259:645–654. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes J M X, Ares M., Jr Depletion of U3 small nucleolar RNA inhibits cleavage in the 5′ external transcribed spacer of yeast pre-ribosomal RNA and impairs formation of 18S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 1991;10:4231–4239. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Intine R V A, Good L, Nazar R N. Essential structural features in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe pre-rRNA 5′ external transcribed spacer. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:695–708. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeppesen C, Stebbins-Boaz B, Gerbi S A. Nucleotide sequence determination and secondary structure of Xenopus U3 snRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:2127–2148. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.5.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kass S, Craig N, Sollner-Webb B. Primary processing of mammalian rRNA involves two adjacent cleavages and is not species specific. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2891–2898. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kass S, Tyc K, Steitz J A, Sollner-Webb B. The U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein functions in the first step of preribosomal RNA processing. Cell. 1990;60:897–908. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90338-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kufel J, Dichtl B, Tollervey D. Yeast Rnt1p is required for cleavage of the pre-ribosomal RNA 3′ ETS but not the 5′ ETS. RNA. 1999;5:909–917. doi: 10.1017/s135583829999026x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labhart P, Reeder R H. Characterization of three sites of RNA 3′ end formation in the Xenopus ribosomal gene spacer. Cell. 1986;45:431–443. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange T S, Borovjagin A, Maxwell E S, Gerbi S A. Conserved Boxes C and D are essential nucleolar localization elements of U14 and U8 snoRNAs. EMBO J. 1998;17:3176–3187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lange T S, Ezrokhi M, Borovjagin A, Rivera-León R, North M T, Gerbi S A. Nucleolar localization elements of Xenopus laevis U3 snoRNA. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2973–2985. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.10.2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S J, Baserga S J. Functional separation of pre-rRNA processing steps revealed by truncation of the U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein component, Mpp10. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13536–13541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S J, Baserga S J. Imp3p and Imp4p, two specific components of the U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein that are essential for pre-18S rRNA processing. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5441–5452. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H V, Zagorski J, Fournier M J. Depletion of U14 small nuclear RNA (snR128) disrupts production of 18S rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1145–1152. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.3.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang W Q, Fournier M J. U14 base-pairs with 18S rRNA: a novel snoRNA interaction required for rRNA processing. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2433–2443. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.19.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lygerou Z, Allmang C, Tollervey D, Séraphin B. Accurate processing of a eukaryotic precursor ribosomal RNA by ribonuclease MRP in vitro. Science. 1996;272:268–270. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Méreau A, Fournier R, Grégoire A, Mougin A, Fabrizio P, Lührmann R, Branlant C. An in vivo and in vitro structure-function analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae U3A snoRNP: protein-rRNA contacts and base-pair interactions with pre-ribosomal RNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;173:552–571. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra R K, Eliceiri G L. Three small nucleolar RNAs that are involved in ribosomal RNA precursor processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4972–4977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrissey J P, Tollervey D. Yeast snR30 is a small nucleolar RNA required for 18S rRNA synthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2469–2477. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrissey J P, Tollervey D. Birth of the snoRNPs: the evolution of RNase MRP and the eukaryotic pre-rRNA processing system. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:78–82. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88962-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mougey E B, Pape L K, Sollner-Webb B. A U3 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein-requiring processing event in the 5′ external transcribed spacer of Xenopus precursor rRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5990–5998. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.5990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narayanan A, Speckman W, Terns R, Terns M P. Role of the box C/D motif in localization of small nucleolar RNAs to coiled bodies and nucleoli. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2131–2147. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.7.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peculis B A, Steitz J A. Disruption of U8 nucleolar snRNA inhibits 5.8S and 28S rRNA processing in the Xenopus oocyte. Cell. 1993;73:1233–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90651-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddy R, Busch H. Small nuclear RNA and RNA processing. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1983;30:127–162. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samarsky D A, Fournier M J. Functional mapping of the U3 small nucleolar RNA from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3431–3444. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savino R, Gerbi S A. In vivo disruption of Xenopus U3 snRNA affects ribosomal RNA processing. EMBO J. 1990;9:2299–2308. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savino R, Gerbi S A. Preribosomal RNA processing in Xenopus oocytes does not include cleavage within the external transcribed spacer as an early step. Biochimie. 1991;73:805–812. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90060-e. . (Erratum, 78:295, 1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmitt M E, Clayton D A. Nuclear RNase MRP is required for correct processing of pre-5.8S rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7935–7941. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma K, Tollervey D. Base pairing between U3 small nucleolar RNA and the 5′ end of 18S rRNA is required for pre-rRNA processing. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6012–6019. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma K, Venema J, Tollervey D. The 5′ end of the 18S rRNA can be positioned from within the mature rRNA. RNA. 1999;5:678–686. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tollervey D. A yeast small nuclear RNA is required for normal processing of pre-ribosomal RNA. EMBO J. 1987;6:4169–4175. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tycowski K T, Shu M-D, Steitz J A. Requirement for intron-encoded U22 small nucleolar RNA in 18S ribosomal RNA maturation. Science. 1994;266:1558–1561. doi: 10.1126/science.7985025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Udem S A, Warner J R. The cytoplasmic maturation of a ribosomal precursor ribonucleic acid in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:1412–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Venema J, Tollervey D. RRP5 is required for formation of both 18S and 5.8S rRNA in yeast. EMBO J. 1996;15:5701–5714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venema J, Tollervey D. Ribosome synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Genet. 1999;33:261–311. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Venema J, Henry Y, Tollervey D. Two distinct recognition signals define the site of endonucleolytic cleavage at the 5′ end of yeast 18S rRNA. EMBO J. 1995;14:4883–4892. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young R A, Steitz J A. Complementary sequence 1700 nucleotides apart form a ribonuclease III cleavage site in Escherichia coli ribosomal precursor RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3593–3597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu Y-T, Nilsen T W. Sequence requirements for maturation of the 5′ terminus of human 18S rRNA in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9264–9268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]