Abstract

It is often difficult to histologically differentiate among endometrial dedifferentiated carcinoma (DC), endometrioid carcinoma (EC), serous carcinoma (SC), and carcinosarcoma (CS) due to the presence of solid components. In this study, we aimed to categorize these carcinomas according to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) classification using a small custom-made cancer genome panel (56 genes and 17 microsatellite regions) for integrated molecular diagnosis. A total of 36 endometrial cancer cases with solid components were assessed using IHC, next-generation sequencing (NGS), and the custom-made panel. Among 19 EC cases, six were categorized as MMR-deficient (MMR-d) and eight were classified as having a nonspecific molecular profile. Three EC cases were classified as POLE mutation (POLEmut)-type, which had a very high tumor mutation burden (TMB) and low microsatellite instability (MSI). Increased TMB and MSI were observed in all three DC cases, classified as MMR-d with mutations in MLH1 and POLD1. Except for one case classified as MMR-d, all SC cases exhibited TP53 mutations and were classified as p53 mutation-type. SC cases also exhibited amplification of CCND1, CCNE1, and MYC. CS cases were classified as three TCGA types other than the POLEmut-type. The IHC results for p53 and ARID1A were almost consistent with their mutation status. NGS analysis using a small panel enables categorization of endometrial cancers with solid proliferation according to TCGA classification. As TCGA molecular classification does not consider histological findings, an integrated analytical procedure including IHC and NGS may be a practical diagnostic tool for endometrial cancers.

Keywords: microsatellite instability, tumor mutation burden, integrated molecular diagnosis, endometrial cancers, solid proliferation

Introduction

Dedifferentiated carcinoma (DC) is a rare endometrial cancer accounting for 2% of all endometrial cancers. It is composed of well differentiated endometrioid carcinoma (EC) and undifferentiated carcinoma [1]. Contrastingly, carcinosarcoma (CS) is composed of high-grade carcinomatous and sarcomatous components, with the latter containing homologous and/or heterologous elements [1]. Identifying heterologous elements via immunohistochemistry (IHC) is helpful for differentially diagnosing DC and CS cases. However, in some cases, both the dedifferentiated part of DC and the sarcomatous part of CS exhibit similar nonspecific vimentin and keratin expression [2]. Grade 2 (G2) and Grade 3 (G3) EC cases also exhibit variable vimentin and keratin expression [3], indicating that the value of IHC for vimentin and keratin is limited in endometrial cancer diagnosis. Therefore, developing a novel integrated strategy combining histological and genomic analyses is necessary for the differential diagnosis of DC, EC, serous carcinoma (SC), and CS with areas of solid proliferation [4-6].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has recently become a standard procedure for cancer genomic analysis [7, 8]. This is largely due to the development of improved techniques, which allow the use of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues and liquid-based cytology specimens [9, 10]. We previously established a cancer gene panel comprising 60 genes and 17 microsatellite foci. This customized panel was used to analyze genetic profiles using FFPE tissues of endometrial cancers in terms of gene mutations, tumor mutation burden (TMB), and microsatellite instability (MSI) [11]. In this study, the above panel was further modified to detect POLE for evaluating gene alterations that can categorize DC, CS, SC, and EC with solid proliferation into MMR-deficient (MMR-d), p53 mutation (p53mut)-type, POLE mutation (POLEmut)-type, and cases with no specific molecular profile (NSMP) according to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) classification. Furthermore, we used an IHC panel containing mismatch repair (MMR) proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6), p53, ARID1A, PTEN, vimentin, WT-1, estrogen receptor (ER), and cyclin D1 (CycD1), which is routinely available for FFPE tissue sections in pathology laboratories. This panel was used to determine whether an integrative approach utilizing IHC and NGS could aid pathologists in the differential diagnosis and histology-dependent classification of endometrial cancers.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval and Samples

All patients were registered at the Clinical Research of Cancer Gene Panel Analysis of Gynecologic Cancers Study, which was conducted from January 2019 to October 2021 at the Kagoshima University Hospital. The clinical samples used in this study were approved by the Ethics Committees for Clinical and Epidemiologic Research at Kagoshima University (approval number: 180215) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Among the 155 cases entered, 36 cases, including 16 G2 and 3 G3 EC cases, 3 DC cases, 4 CS cases, 9 SC cases, and 1 large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) case with areas of solid proliferation were included in this study. Clear cell carcinoma (CCC) is considerably less frequent in the Gynecologic Cancers Study in our hospital, therefore, CCC cases were excluded from this study. No patients with undifferentiated carcinoma were included.

Tissue Preparation and Diagnostic Criteria

Resected tissues obtained by hysterectomy were fixed with 10% neutral phosphate-buffered formalin, routinely processed for paraffin embedding, and sectioned for hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, IHC, and NGS. Pathological diagnoses were made according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system [1]. The following criteria were used for diagnosing SC: carcinoma showing complex papillary, glandular and/or solid growth patterns with marked nuclear pleomorphism; CS: admixture of high-grade müllerian type carcinomatous elements and apparent mesenchymal morphology, as determined using homologous (CD10, desmin, alpha-smooth muscle actin) or heterologous (myogenin, MyoD1, S-100) IHC markers [12, 13]; DC: biphasic tumor consisting of EC and undifferentiated nested or trabecular architecture with no gland formation; EC: glandular proliferation with smooth luminal outline, composed of columnar cells with pseudostratified nuclei. Grading criteria of EC: Grade 1, 2, and 3, respectively, exhibit ≤5%, 6–50%, and >50% solid growth was used.

The dedifferentiated parts of DC are positive for epithelial marker expression in scattered cells, and mesenchymal elements of CS are weakly positive or negative for these markers; hence, diffuse expression of keratins (AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2) and EMA was used to differentiate endometrial cancers [1].

Criteria for Evaluating the IHC Results of MMR Proteins, p53, ARID1A, and PTEN

The antibodies used for IHC are listed in Online Resource 1. MMR-proficient (MMR-p) was defined as positive nuclear staining for all MMR proteins (MLH1, PMS2, MSH2, and MSH6). MMR-d was defined as the complete absence of nuclear staining for any MMR proteins [14]. p53 expression resulting in scattered nuclear staining with variable intensity was categorized as wildtype (wt p53) pattern, whereas diffuse and strong nuclear overexpression or a complete loss of expression was defined as mutation (mt p53) pattern. For ER, vimentin, WT-1, CycD1, ARID1A, and PTEN expression, the percentage of marker-positive areas assessed in the tumor section were evaluated in 10% increments. In areas of glandular or carcinomatous and solid proliferation, the expression of ARID1A and PTEN was categorized as very low at <10%, and as lost at <5%.

Cancer Panel Design, DNA Isolation, and NGS Analysis

A cancer panel was redesigned by making a minor modification of the previous panel [11] to include 56 cancer-related genes and 17 microsatellite foci selected from the QIAseq Targeted DNA Custom Panel (Qiagen, Reston, VA, United States), with 2,640 primers for the regions of interest (194,131 bp) and an average exon coverage of 99.87% (Online Resource 2). Whole blood DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kits (Qiagen). Cancer DNA was obtained from three to six sections (10 μm thickness) of FFPE tissues, representing more than 30% of the cancerous tissue. When cancer is composed of various histology, several tissue sections were subjected to NGS analysis if separate sampling of each element was possible by micro or macrodissection. The FFPE sections were first incubated with proteinase K (Promega, Madison, WI, United States) for 15 h at 70°C, followed by incubation at 98°C for 1 h in the lysis buffer (Promega). Following centrifugation (12,000 × g, 5 min at 4°C), the supernatants were applied to a Maxwell® RSC DNA FFPE kit and the Maxwell 16 system (Promega). The concentrations of extracted DNA were measured using Qubit 3.0 dsDNA BR assay kits (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, United States), and the DNA quality was monitored using the QIAseq DNA quantiMIZE kit (Qiagen). DNA with a quality check score <0.04 was considered high-quality DNA [11]. NGS was performed using a MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) as previously described [11].

Sequence data were annotated as previously described using the Qiagen Web Portal service (https://www.qiagen.com./us/shop/genes-and-pathways/data-analysis-center-overview-page/) and Mitsubishi Space Software (Amagasaki, Hyogo, Japan) [11, 15]. The COSMIC database and human genome reference GRCh37 (hg19) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCF_000001405.13/) were used as references. The sequence data obtained from whole blood DNA were used only as a reference, and germline analysis was not performed.

Calculation of Copy Number Alteration

To calculate the copy number (CN) from the baseline data used for counting correction per amplicon, the number of reads sequenced in each amplicon was counted, and the reads per million (RPM) value was determined. The RPM coefficient of variation (CV), mean, and median value per amplicon in at least 100 FFPE samples were calculated. The RPM median of the amplicons with a CV < 0.34 and mean > 10 was set as the baseline. The number of reads sequenced in each 56‐panel amplicon was counted in the sample to calculate the CN of each sample. The baseline ratios {log2 ratio [ = log2 (sample RPM/baseline RPM median)]} in amplicons that satisfied the conditions of CV < 0.34 and mean >10 were counted, and the overall SD and median value of the log2 ratio for each gene was calculated. The genes with a log2 ratio median value >2 SD were categorized as amplified, while the genes with a log2 ratio median value <−2 SD were categorized as gene loss [16].

Calculation of Cut-Off Values for TMB and MSI Scores

Missense mutations with more than 10% variant allele frequency, including nonsynonymous mutations and internal deletions, were counted as somatic mutations. The TMB was calculated as the number of single nucleotide variants million per base pairs (Mbp) of the DNA sequence [17, 18], and the MSI scores were determined using MSIsensor (ver. 1.0) [19, 20]. To determine the cutoff values of MSI and TMB using receiver operator characteristic curves, 59 samples from 41 endometrial cancer cases were used.

Statistical Analysis

All values were expressed as the mean ± standard error. Significant differences were identified using student’s or Welch’s t-tests and were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

IHC Profiles

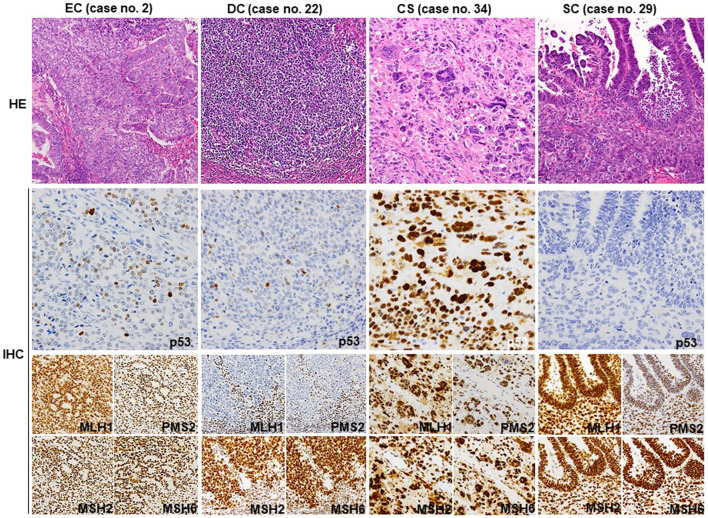

The IHC results regarding the MMR proteins, p53, ARID1A, PTEN, WT-1, ER, CycD1, and vimentin are summarized in Table 1 (extracted) and Online Resource 3 (detailed), and representative photomicrographs are shown in Figure 1. Among 19 EC cases, 16 showed the wt p53 pattern, and three showed the mt p53 pattern. Six EC and three DC cases showed loss of MMR protein expression. PTEN expression was very low (<10% area showing expression) or lost (<5% area showing expression) in all DC (3/3) and most EC cases (12/19), while ARID1A was lost less frequently in DC (1/3) and EC cases (7/19). All SC (9/9) and some CS (2/4) cases exhibited the mt p53 pattern in carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements. Three CS cases were MMR-p, whereas one was MMR-d. Almost all SC cases were MMR-p (8/9). PTEN expression was lost in one CS and five SC cases. ARID1A expression was well preserved in CS (3/4) and SC (8/9) cases. One LCNEC exhibited MMR-p and had mt p53 as well as diffuse PTEN and ARID1A expression. The expression of WT-1, vimentin, CycD1, and ER was variable in all carcinoma types. The genomic correlation between CycD1, ER, PTEN, and ARID1A is described later.

TABLE 1.

Summary for histological diagnosis, expression of MMR proteins and p53, and genomic profile in 36 cases.

| Case no. | Age | Histological diagnosis | MMR | p53 | MSI | TMB | SNV and delins mutations | TCGA type | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 | MLH1 | PMS2 | MSH2 | MSH6 | POLE | POLD1 | TERT | |||||||||

| 1 | 60 | EC (G2) | pro. | wt | Low | High | NSMP | |||||||||

| 2 | 54 | EC (G1) | pro. | wt | Low | U-high | p.Val63Met | c.2389G>T | p.Val411Leu | POLEmut | ||||||

| EC (G2) | Low | U-high | c.2389G>T | p.Val411Leu | ||||||||||||

| 3 | 67 | EC (G2) | pro. | wt | Low | Low | NSMP | |||||||||

| 4 | 68 | EC (G2) | def. | wt | High | High | MMR-d | |||||||||

| 5 | 63 | EC (G2) | pro. | wt | Low | Low | NSMP | |||||||||

| 6 | 64 | EC (G3) | def. | wt | High | High | p.Arg202Cys | MMR-d | ||||||||

| 7 | 59 | EC (G2) | def. | wt | High | High | p.Pro991Leu | MMR-d | ||||||||

| 8 | 55 | EC (G2) | pro. | wt | Low | Low | NSMP | |||||||||

| 9 | 60 | EC (G2) | def. | wt | High | High | p.Phe22fs | MMR-d | ||||||||

| 10 | 61 | EC (G2) | pro. | wt | Low | Low | NSMP | |||||||||

| 11 | 78 | EC (G3) | def. | wt | High | U-high | p.Arg175His | p.Met491fs | MMR-d | |||||||

| 12 | 60 | EC (G2) | pro. | wt | Low | Low | NSMP | |||||||||

| 13 | 55 | EC (G2) | pro. | mt | Low | U-high | p.Arg213* | p.Arg107Trp p.Arg134Gln p.Arg427Cys |

p.Asp758Asn | p.Arg298Gln p.Lys632Arg p.Glu641* p.Glu995Lys |

p.Pro286Ser p.Val411Leu |

p.Ser579Asn c.*334C>T |

POLEmut | |||

| 14 | 65 | EC (G2) | gld. | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Arg273Cys | p53mut | |||||||

| solid | pro. | mt | Low | Low | ||||||||||||

| 15 | 68 | EC (G2) | gld. | pro. | wt | Low | Low | c.903+2T>A | NSMP | |||||||

| solid | pro. | wt | Low | High | c.903+2T>A | |||||||||||

| 16 | 55 | EC (G3) | pro. | mt | Low | Low | c.993+1G>T | p53mut | ||||||||

| 17 | 73 | EC (G2) | gld. | pro. | wt | Low | Low | NSMP | ||||||||

| solid | pro. | wt | Low | Low | ||||||||||||

| 18 | 53 | EC (G2) | gld. | def. | wt | High | Low | p.Glu613_Phe614del | p.Arg678Trp | MMR-d | ||||||

| solid | def. | wt | High | U-high | p.Glu613_Phe614del | c.3582+5C>T | p.Arg678Trp | |||||||||

| 19 | 56 | EC (G2) | gld. | pro. | wt | Low | U-high | p.Glu483* | p.Arg1201Gln p.Glu1234* |

p.Pro286Arg | POLEmut | |||||

| solid | pro. | wt | Low | U-high | p.Glu483* | p.Arg240Gln p.Glu1322* |

p.Pro286Arg | |||||||||

| 20 | 51 | DC | EC (G1) | High | High | p.Asp289dup | MMR-d | |||||||||

| De | def. | wt | High | High | p.Ser388Phe | p.Asp289dup | p.Ala288Val | |||||||||

| 21 | 57 | DC | EC (G3) | def. | wt | High | High | p.Lys373fs | p.Ala288Val p.Trp371Cys p.Arg481Gly |

MMR-d | ||||||

| EC (G 1) | High | High | p.Asn287fs | p.Tyr581His | p.Trp371Cys | |||||||||||

| De | High | High | p.Lys373fs | p.Ala69Thr | p.Tyr581His | p.Trp371Cys | ||||||||||

| 22 | 71 | DC | EC (G1) | High | High | p.Ser577Ser p.Trp712* |

MMR-d | |||||||||

| De | def. | wt | High | High | p.Ser577Ser p.Trp712* |

p.Asp1013fs | ||||||||||

| 23 | 64 | SC | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Arg249Ser | p53mut | ||||||||

| 24 | 67 | SC | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Gly245Ser p.Leu43fs |

p53mut | ||||||||

| 25 | 57 | SC | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Arg248Gln | p53mut | ||||||||

| 26 | 63 | SC | Ad | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Ile255Ser | p53mut | |||||||

| Spn | Low | Low | p.Ile255Ser | |||||||||||||

| 27 | 72 | SC | def. | mt | High | U-high | p.Arg306* | p.Arg352His c.2466+4C>T |

p53mut/ MMR-d | |||||||

| 28 | 75 | SC | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Ser241Phe | p53mut | ||||||||

| 29 | 70 | SC | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Gln144* | p53mut | ||||||||

| 30 | 65 | SC | pro. | mt | Low | Low | c.817C>T | p53mut | ||||||||

| 31 | 77 | SC | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Ala276Gly | p53mut | ||||||||

| 32 | 80 | CS | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Asn239Ser | p53mut | ||||||||

| 33 | 58 | CS | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Cys176Phe c.706T>A |

p53mut | ||||||||

| 34 | 63 | CS | Car | pro. | wt | Low | Low | NSMP | ||||||||

| Src | Low | Low | ||||||||||||||

| 35 | 64 | CS | Car | def. | wt | High | High | MMR-d | ||||||||

| Src | High | High | ||||||||||||||

| 36 | 63 | LCNEC | pro. | mt | Low | Low | p.Phe113Ser | p53mut | ||||||||

EC, endometrioid carcinoma; gld., glandular part; solid, solid part; DC, dedifferentiated endometroid carcinoma; CS, carcinosarcoma; SC, serous carcinoma; LCNEC, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; De, dedifferentiated part; Ad, adenocarcinoma part; Car, carcinomatous part; Sar, sarcomatous part; Spn, spindle cell part; MMR, mismatch repair protein; MSI, macrisatellite instability; TMB, tumor mutation burden; CNA, copy number alteration; Amp, amplification; SNV, single nucleotide variant; U-high, ultra high; pro., proficient; def., deficient; wt, wild-type; mt, mutation; PLOEmut, POLE, mutation; MMR-d, MMR-deficient; NSMP, no specific molecular profile; p53mut, p53 mutation.

FIGURE 1.

Representative histology and IHC of p53 and MMR proteins. Representative HE sections from G2 EC (no. 2) showing well differentiated glandular and less differentiated solid areas. A few p53-positive tumor cells are observed, indicating wt p53 expression. All four MMR proteins are diffusely positive. The dedifferentiated part of DC (no. 22) exhibits wt p53 expression pattern and loss of MLH1 and PMS2 expression. Stromal lymphocytes also show a positive reaction as an internal control. The sarcomatous element of CS (no. 34) shows diffuse staining for p53 and all four MMR proteins. SC (no. 29) shows complete loss of p53 expression in both glandular and solid elements. The MMR protein expression is well preserved. CS, carcinosarcoma; SC, serous carcinoma; HE, hematoxylin and eosin (Original magnification: ×200); IHC, immunohistochemistry. (Original magnification: p53 × 400, MMR ×200).

Cutoff Values of TMB and MSI Scores

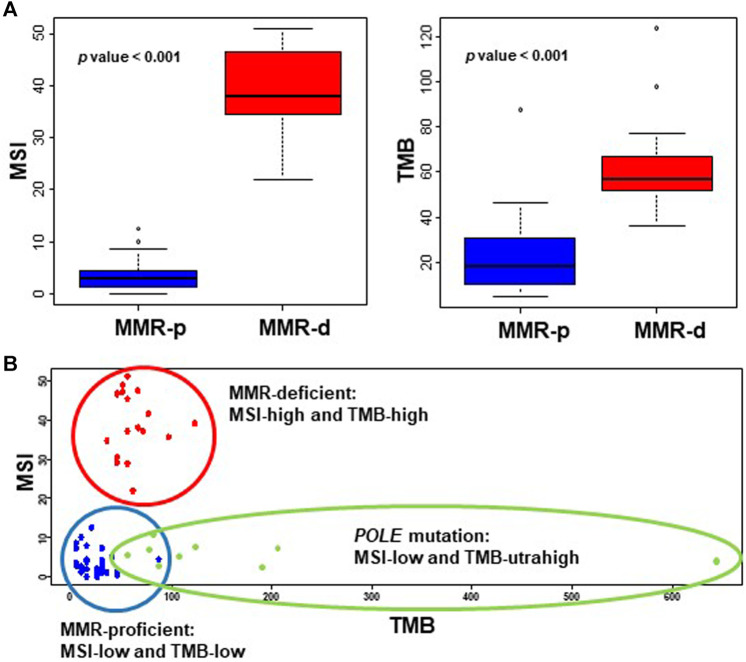

The TMB values of wildtype and mutated POLE cases were 36.3 ± 3.8 and 175.1 ± 61.0 (p = 0.026), respectively, and the cutoff value for TMB-ultrahigh (TMB-UH) was calculated as 72. Excluding the POLEmut cases, the TMB values of MMR-p and MMR-d cases were 22.5 ± 3.0 and 63.0 ± 5.1, respectively (p < 0.001), and the cutoff values for TMB-high (TMB-H) and -low (TMB-L) were calculated to be 42. Similarly, the MSI values of MMR-p and MMR-d cases were 3.6 ± 0.5 and 38.7 ± 2.0, respectively (p < 0.001), and the cutoff values for the differentiation of MSI-high (MSI-H) and -low (MSI-L) were estimated to be 13. The distribution of TMB and MSI scores of the tested endometrial cancers for cutoff value estimation is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Values of MSI and TMB in endometrial cancers. (A) The MSI (left panel) and TMB (right panel) scores of MMR-d EC cases are significantly higher than those of EC cases that are MMR-p. (B) The MSI and TMB scores of endometrial cancers are plotted as a scattergram, showing clear distinction of MMR-p (blue dot) and MMR-d cases (red dot), and TMB-ultrahigh POLE mutation cases (green dot). MMR, mismatch repair; MSI, microsatellite instability; TMB, tumor mutation burden; MMR-p, mismatch repair-proficient; MMR-d, mismatch repair-deficient.

Genomic Profile

Genomic profiles of 36 cases are shown in Table 1 (extracted) and Online Resource 4 (detailed). All three DC cases (no. 20–22) carried MLH1 and POLD1 mutations with TMB-H and MSI-H, and exhibited variable mutations in PTEN, ARID1A, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, and CTNNB1. The TERT coding region was mutated in two DC cases, although the promoter was not. All 19 EC cases exhibited common mutations in PTEN, ARID1A, CTNNB1, PIK3CA, and PIK3R1. Among the 19 cases, 16 cases (except for case no. 2, 13, and 19) included MMR-p and MMR-d cases and exhibited higher TMB scores than did the SC cases (Table 2). Six EC cases that were MMR-d had higher TMB and MSI scores than the ten MMR-p cases and were classified as TMB-H and MSI-H (Table 3). Three EC cases (no. 2, 13, and 19) that harbored a POLE mutation were classified as TMB-UH and MSI-L.

TABLE 2.

MSI and TMB in each histological subtype.

| n | MSI score | EC | CS | SC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | 3 | 39.2 ± 5.5 | p = 0.037 | Ns | p < 0.001 |

| EC | 16 | 16.5 ± 5.0 | Ns | ns | |

| CS | 4 | 20.5 ± 10.2 | ns | ||

| SC | 9 | 7.9 ± 3.6 | |||

| n | TMB score | EC | CS | SC | |

| DC | 3 | 68.7 ± 4.6 | ns | p = 0.012 | p = 0.013 |

| EC | 16 | 43.2 ± 6.9 | Ns | p = 0.041 | |

| CS | 4 | 23.2 ± 11.6 | ns | ||

| SC | 9 | 21.8 ± 9.9 |

The MSI, and TMB, scores are presented as mean ± standrad error. EC with POLE, mutation is excluded; MSI, microsatelliete instability; TMB, tumor mutation burden; EC, endometrioid carcinoma; CS, carcinosarcoma; SC, serous carcinoma; ns, not significant.

TABLE 3.

MSI and TMB in EC.

| EC | n | MSI score | TMB score |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMR-p | 10 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 26.3 ± 3.5 |

| MMP-d | 6 | 40.4 ± 3.7 | 66.1 ± 12.8 |

| p value | <0.0001 | 0.012 | |

MSI, microsatellite instability; TMB, tumor mutation burden; EC, endometroid carcinoma; MMR-p, mismatch repair-proficient; MMR-d, mismatch repair-deficient.

Among the four CS cases (no. 32–35), two contained mutations in TP53 and exhibited mt p53 expression. Furthermore, three CS cases, one with mutated and two with wildtype TP53, exhibited amplification of MYC, CCNE1, or CCND1. All CS cases were MMR-p (MSI-L and TMB-L) and showed no mutations in MMR, except for one case that exhibited a loss of MLH1 and PMS2 expression (MSI-H and TMB-H) without any mutations in MLH1 and PMS2. IHC and NGS profiles of eight SC cases, displaying mt p53 expression and MMR-p characteristics were classified as MSI-L and TMB-L. One CS case (no. 32) showed ERBB2 amplification. Among the eight SC cases, five showed amplification in MYC, CCNE1, or CCND1. One SC case (no. 27) exhibited MMR-d with wildtype MMR and was classified as TMB-UH and MSI-H. LCNEC (no. 36) exhibited an SC-like profile with mutations in TP53 and PIK3CA. Other mutations such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM were detected in some cases (nos. 2, 4, 5, 18, 19, 20, 22, 27, and 36) (Online Resource 4).

For the tumors composing of heterogenous elements, the genomic profile was evaluated separately for each element suing two or three FFPE sections in six cases of EC (no. 2, 14, 15, and 17–19), two of CS (nos. 34 and 35), one of SC (no. 26), and three of DC (nos. 20, 21, and 22). The genomic profiles were not exactly matched between the heterogenous elements, but were not so different as much as TCGA classification was revised (Online Resource 4).

Correlation Between the Results of Genomic and IHC Analyses of p53, ARID1A, and PTEN

The correlation between the genomic and IHC analyses of ARID1A and PTEN is presented in Online Resource 5. Most CS (3/4) and SC cases (8/9) exhibiting high ARID1A expression (>90% of the positive area) had no mutations. Fourteen EC cases (14/19) harbored frameshift, nonsense mutations or splice variants. Among these, eight cases exhibited a loss of ARID1A expression (<5% of the positive area). PTEN expression was lost in one CS case with gene alterations (1/4). Although SC cases did not display PTEN mutations (9/9), five cases did not express PTEN. Among 19 EC cases, 18 carried PTEN mutations and 13 accompanied by a loss of PTEN expression (<5% of the positive area). As previously reported [21, 22], ARID1A expression was almost consistent with ARID1A mutations in EC, CS, and SC cases, and that of PTEN was consistent with PTEN mutations in EC cases. For CycD1 and ER, a correlation between genomic and IHC analysis results could not be established due to the limited number of cases exhibiting these gene mutations (data not shown). The status of TP53 mutation matched well with the p53 IHC results in EC, SC, CS, and LCNEC cases (33/36), except for two EC cases (no. 6 and 11) and one DC case (no.21) that exhibited wt p53 IHC but harbored TP53 mutations.

TCGA Classification

Based on TCGA classification [23], EC cases were classified as POLEmut (3/19), MMR-d (6/19), NSMP (8/19), and p53mut (2/19), and all DC cases were categorized as MMR-d (3/3). CS cases were classified as MMR-d (1/4), p53mut (2/4), and NSMP (1/4). Most SC cases were classified as p53mut (8/9), and one was classified as MMR-d (1/9) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Distribution of TCGA classification*.

| EC | DC | CS | SC | LCNEC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLEmut | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MMR-d | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| p53mut | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 1 |

| NSMP | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 36 | 19 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 1 |

*Case no. 27, which exhibits both p53mut and MMR-d features, is categorized as p53mut type. EC, endometrioid carcinoma; DC, dedifferentiated edometrioid carcinoma; CS, carcinosarcoma; SC, seous carcinoma; LCNEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; PLOEmut, POLE, mutation; MMR-d, mismatch repair-deficient; NSMP, no specific molecular profile; p53mut, p53 mutation.

Discussion

Our study indicated that NGS-based genomic analysis using the custom-made small panel could be used to evaluate TMB and MSI and for the detection of gene mutations, thus aiding in the categorization of endometrial cancers with solid proliferation according to TCGA classification.

DC comprises well differentiated EC and undifferentiated carcinoma. Therefore, it is often difficult to differentiate DC from CS and EC. Differential diagnosis by HE staining alone is challenging when CS tissues exhibiting only subtle spindle cells or ambiguous heterologous sarcomatous elements, such as chondrosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma, and less evident serous morphology are involved [24]. Differentiation markers, such as myogenin, CD10, and desmin, are used to investigate the presence of heterologous or homologous sarcomatous elements in CS tissues. However, sarcomatous markers may be expressed focally even in carcinomatous areas [2, 3]. Moreover, the epithelial markers (keratins and EMA) were sometimes weakly expressed in the scattered cells of dedifferentiated elements of DC or absent in the sarcomatous parts of CS tissues [1]. Therefore, it may be difficult to differentiate between DC and CS, even with additional analysis using IHC. The effects of interobserver variability on the diagnosis of DC, CS, and EC are well established [25, 26]. Therefore, IHC results alone may be insufficient for distinguishing these cancers. Consequently, genomic analysis appears to be a more suitable option for developing an integrated strategy for the differential diagnosis of endometrial cancers [27-29].

We found that DC cases typically harbored mutations in MLH1 and POLD1 as well as exhibited variable mutations in PTEN, ARID1A, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, and CTNNB1 with MSI-H and TMB-H. Contrastingly, most SC cases and some CS cases (MSI-L and TMB-L) carried TP53 mutations, while PTEN, ARID1A, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, and CTNNB1 mutations were less frequent. Since CS is a biphasic tumor with a carcinomatous element exhibiting high-grade müllerian type carcinoma [12, 13, 24], CS cases harbored a TP53 mutation, similar to SC [30, 31]. MMR-d cases, which are mutually exclusive of TP53 mutations [32, 33], are rarely observed in CS or SC (4–6%) [24, 30, 34-36]. As previously reported [37-39], our study also demonstrated that CS and SC cases typically exhibited amplification in MYC, CCND1, and CCNE1. These findings were distinct from those in DC cases.

Using IHC as a tool for p53 and MMR protein analysis may facilitate differential diagnosis of DC and CS, as demonstrated by a recent study [24]. Our results substantiated this finding and further elucidated the benefits associated with analysis of MMR proteins by IHC. However, some studies have indicated that CS exhibits a high rate of MMR-d cases (10–41%) [40, 41]. We propose that some DC cases, rather than true CS cases, may have been included in these studies, as many cases (>60%) demonstrated endometrioid morphology in the epithelial components [41]. Another study also demonstrated that DC cases were distributed in all TCGA classification categories [42]. The histological diagnosis of DC was based on the absence of E-cadherin expression and positive ZEB1 immunoreaction. These criteria were different from the diagnostic criteria used in our current study. In another report, a certain population of endometrial DC exhibited concurrent loss of ARID1A and ARID1B and loss of SMARCA4 or SMARCB1 expression [43]. Therefore, the use of the histological criteria and immunophenotyping in DC remains controversial.

EC comprises glandular and solid (>5%) areas diagnosed as G2 or G3 EC, based on the percentage of the solid components and nuclear atypia [44]. In EC, solid components are more evenly distributed and typically have indistinct borders between glandular parts. Meanwhile, dedifferentiated solid areas in DC are well demarcated from glandular parts [1]. However, the differentiation of EC with solid components from DC is sometimes difficult, especially when diagnoses are based on histological findings alone. MMR-d was shared between wildtype POLE EC and DC. As G2/G3 EC commonly exhibits TP53 mutations secondary to MMR mutations [45], p53 IHC is not always useful for differentiating EC, DC, and CS from SC. Furthermore, like the SC case (no. 27) displayed both p53mut and MMR-d features, 3% of endometrial cancers exhibit other genomic features in addition to p53 abnormalities [45].

In accordance with previous studies [21, 22, 46], a high concordance was observed between ARID1A IHC and mutation status, while that between PTEN IHC and mutation was also high in EC but not in SC cases. Even IHC detects a greater population of PTEN loss than does NGS analysis [21], the frequency of SC cases showing loss of PTEN expression with no PTEN mutation might be unusually high in our study (five out of nine cases). The reported frequencies of SCs showing loss of PTEN expression range from 0 to 11% [47-50]. Since the method of PTEN IHC is often poorly reproducible [21, 51, 52], we cannot exclude a possibility of false negative PTEN IHC due to technical issues.

Compared with IHC-based analyses of MMR proteins, characteristic IHC profiles are not known for being used for the differential diagnosis of POLEmut EC from DC. The most characteristic feature of EC with POLEmut is ultrahigh TMB and low MSI scores [23]. However, to the best of our knowledge, a targeting antibody detecting mutated-POLE protein is unavailable, and no characteristic histological findings associated with POLEmut-type EC are presently known.

Overall, MLH1, POLD1, and TERT mutations in DC may be considered a characteristic molecular profile that can be used to distinguish it from EC. Pathogenic POLD1 mutations have been observed in colorectal cancers and polymerase proofreading-associated polyposis syndrome [53]. Compared with POLE, POLD1 mutations are less frequently observed in endometrial cancers, although a few POLD1 mutations have been reported in G3 EC [54]. The sample size used to assess DC in this study was considerably small for determining the significance of TERT and POLD1 mutations for tumor cell dedifferentiation in EC.

As endometrial LCNEC also demonstrates undifferentiated solid elements, LCNEC should be considered in the differential diagnosis of endometrial cancer with solid proliferation. However, LCNEC diagnosis is not challenging due to its distinct IHC profile [55]. Herein, LCNEC was MMR-p and exhibited mt p53 and diffuse ARID1A expression, and its NGS profile was similar to that of SC. Although a previous study indicated that LCNEC should be classified as a variant of DC [56], a recent report has indicated that the nature of endometrial LCNEC is heterogeneous, and molecular analysis has shown that LCNEC may be grouped under any TCGA classification [57].

In summary, the feasibility of using a small NGS cancer panel to facilitate the molecular categorization of endometrial DC, SC, CS, and EC with solid proliferation was investigated. Genomic analyses that detect alterations in TMB, MSI, and gene mutations including MLH1, TERT, POLD1, and POLE, IHC analyses that assess p53 and MMR protein expression, and other conventional IHC including PTEN and ARID1A exhibit significant potential as a practical diagnostic tool for determining endometrial cancer pathology.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the excellent technical assistance of Orie Iwaya and Mai Tokudome at the Department of Pathology, Kagoshima University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Ethics Committees for Clinical and Epidemiologic Research at the Kagoshima University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

YK and IK summarized the pathological and genomic data; TA analyzed and interpreted the sequencing data; KT contributed as a pathologist; SHY, MK, and ST summarized the clinical data; IS, SN, and SEY contributed to genomic data analysis; AT and HK organized the study and wrote the article; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

SN and IS are employed by Mitsubishi Space Software.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.por-journal.com/articles/10.3389/pore.2021.1610013/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Kim K-R, Lax SF, Lazar AJ, Longacre TA, Malpica A, Matias-Guiu X, et al. Tumours of Uterine Corpus. In: The WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial boardFemale Genital Tumours. 5th ed. Lyon: IARC; (2020). p. 245–308. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azumi N, Battifora H. The Distribution of Vimentin and Keratin in Epithelial and Nonepithelial Neoplasms: A Comprehensive Immunohistochemical Formalin- and Alcohol-Fixed Tumors. Am J Clin Pathol (1987) 88:286–96. 10.1093/ajcp/88.3.286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murali R, Davidson B, Fadare O, Carlson JA, Crum CP, Gilks CB, et al. High-grade Endometrial Carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol (2019) 38(Suppl. 1):S40–S63. 10.1097/pgp.0000000000000491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Piulats JM, Guerra E, Gil-Martín M, Roman-Canal B, Gatius S, Sanz-Pamplona R, et al. Molecular Approaches for Classifying Endometrial Carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol (2017) 145:200–7. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bell DW, Ellenson LH. Molecular Genetics of Endometrial Carcinoma. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis (2019) 14:339–67. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carlson J, McCluggage WG. Reclassifying Endometrial Carcinomas with a Combined Morphological and Molecular Approach. Curr Opin Oncol (2019) 31:411–9. 10.1097/cco.0000000000000560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horak P, Fröhling S, Glimm H. Integrating Next-Generation Sequencing into Clinical Oncology: Strategies, Promises and Pitfalls. ESMO Open (2016) 1:e000094. 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chang Y-S, Huang H-D, Yeh K-T, Chang J-G. Identification of Novel Mutations in Endometrial Cancer Patients by Whole-Exome Sequencing. Int J Mol Med (2017) 50:1778–84. 10.3892/ijo.2017.3919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akahane T, Yamaguchi T, Kato Y, Yokoyama S, Hamada T, Nishida Y, et al. Comprehensive Validation of Liquid-Based Cytology Specimens for Next-Generation Sequencing in Cancer Genome Analysis. PLoS One (2019) 14:e0217724. 10.1371/journal.pone.0217724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamaguchi T, Akahane T, Harada O, Kato Y, Aimono E, Takei H, et al. Next‐generation Sequencing in Residual Liquid‐based Cytology Specimens for Cancer Genome Analysis. Diagn Cytopathology (2020) 48:965–71. 10.1002/dc.24511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akahane T, Kitazono I, Yanazume S, Kamio M, Togami S, Sakamoto I, et al. Next-generation Sequencing Analysis of Endometrial Screening Liquid-Based Cytology Specimens: a Comparative Study to Tissue Specimens. BMC Med Genomics (2020) 13:101. 10.1186/s12920-020-00753-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tafe LJ, Garg K, Chew I, Tornos C, Soslow RA. Endometrial and Ovarian Carcinomas with Undifferentiated Components: Clinically Aggressive and Frequently Underrecognized Neoplasms. Mod Pathol (2010) 23:781–9. 10.1038/modpathol.2010.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vita G, Borgia L, Di Giovannantonio L, Bisceglia M. Dedifferentiated Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma of the Uterus. Int J Surg Pathol (2011) 19:649–52. 10.1177/1066896911405987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raffone A, Travaglino A, Cerbone M, Gencarelli A, mollo A, Insabato L, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Immunohistochemistry for Mismatch Repair Proteins as Surrogate of Microsatellite Instability Molecular Testing in Endometrial Cancer. Pathol Oncol Res (2020) 26:1417–27. 10.1007/s12253-020-00811-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu C, Gu X, Padmanabhan R, Wu Z, Peng Q, DiCarlo J, et al. smCounter2: an Accurate Low-Frequency Variant Caller for Targeted Sequencing Data with Unique Molecular Identifiers. Bioinformatics (2019) 35:1299–309. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saotome K, Chiyoda T, Aimono E, Nakamura K, Tanishima S, Nohara S, et al. Clinical Implications of Next‐generation Sequencing‐based Panel Tests for Malignant Ovarian Tumors. Cancer Med (2020) 9:7407–17. 10.1002/cam4.3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Galuppini F, Dal Pozzo CA, Deckert J, Loupakis F, Fassan M, Baffa R. Tumor Mutation burden: from Comprehensive Mutational Screening to the Clinic. Cancer Cel Int (2019) 19:209. 10.1186/s12935-019-0929-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor Mutational burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N Engl J Med (2017) 377:2500–1. 10.1056/nejmc1713444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niu B, Ye K, Zhang Q, Lu C, Xie M, McLellan MD, et al. MSIsensor: Microsatellite Instability Detection Using Paired Tumor-normal Sequence Data. Bioinformatics (2014) 30:1015–6. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johansen AFB, Kassentoft CG, Knudsen M, Laursen MB, Madsen AH, Iversen LH, et al. Validation of Computational Determination of Microsatellite Status Using Whole Exome Sequencing Data from Colorectal Cancer Patients. BMC Cancer (2019) 19:971. 10.1186/s12885-019-6227-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Djordjevic B, Hennessy BT, Li J, Barkoh BA, Luthra R, Mills GB, et al. Clinical Assessment of PTEN Loss in Endometrial Carcinoma: Immunohistochemistry Outperforms Gene Sequencing. Mod Pathol (2012) 25:699–708. 10.1038/modpathol.2011.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khalique S, Naidoo K, Attygalle AD, Kriplani D, Daley F, Lowe A, et al. Optimised ARID1A Immunohistochemistry Is an Accurate Predictor ofARID1Amutational Status in Gynaecological Cancers. J Path: Clin Res (2018) 4:154–66. 10.1002/cjp2.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Kandoth C, Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, et al. Integrated Genomic Characterization of Endometrial Carcinoma. Nature (2013) 497:67–73. 10.1038/nature12113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jenkins TM, Hanley KZ, Schwartz LE, Cantrell LA, Stoler MH, Mills AM. Mismatch Repair Deficiency in Uterine Carcinosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol (2020) 44:782–92. 10.1097/pas.0000000000001434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garg K, Shih K, Barakat R, Zhou Q, Iasonos A, Soslow RA. Endometrial Carcinomas in Women Aged 40 Years and Younger: Tumors Associated with Loss of DNA Mismatch Repair Proteins Comprise a Distinct Clinicopathologic Subset. Am J Surg Pathol (2009) 33:1869–77. 10.1097/pas.0b013e3181bc9866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Han G, Sidhu D, Duggan MA, Arseneau J, Cesari M, Clement PB, et al. Reproducibility of Histological Cell Type in High-Grade Endometrial Carcinoma. Mod Pathol (2013) 26:1594–604. 10.1038/modpathol.2013.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McConechy MK, Ding J, Cheang MC, Wiegand KC, Senz J, Tone AA, et al. Use of Mutation Profiles to Refine the Classification of Endometrial Carcinomas. J Pathol (2012) 228:20–30. 10.1002/path.4056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cuevas D, Valls J, Gatius S, Roman-Canal B, Estaran E, Dorca E, et al. Targeted Sequencing with a Customized Panel to Assess Histological Typing in Endometrial Carcinoma. Virchows Arch (2019) 474:585–98. 10.1007/s00428-018-02516-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jones NL, Xiu J, Chatterjee-Paer S, Buckley de Meritens A, Burke WM, Tergas AI, et al. Distinct Molecular Landscapes between Endometrioid and Nonendometrioid Uterine Carcinomas. Int J Cancer (2017) 140:1396–404. 10.1002/ijc.30537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cherniack AD, Shen H, Walter V, Stewart C, Murray BA, Bowlby R, et al. Integrated Molecular Characterization of Uterine Carcinosarcoma. Cancer Cell (2017) 31:411–23. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen X, Arend R, Hamele-Bena D, Tergas AI, Hawver M, Tong G-X, et al. Uterine Carcinosarcomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol (2017) 36:412–9. 10.1097/pgp.0000000000000346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, Li-Chang HH, Kwon JS, Melnyk N, et al. A Clinically Applicable Molecular-Based Classification for Endometrial Cancers. Br J Cancer (2015) 113:299–310. 10.1038/bjc.2015.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, Yang W, Lum A, Senz J, et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: a Simple, Genomics-Based Clinical Classifier for Endometrial Cancer. Cancer (2017) 123:802–13. 10.1002/cncr.30496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meyer LA, Broaddus RR, Lu KH. Endometrial Cancer and Lynch Syndrome: Clinical and Pathologic Considerations. Cancer Control (2009) 16:14–22. 10.1177/107327480901600103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mills AM, Liou S, Ford JM, Berek JS, Pai RK, Longacre TA. Lynch Syndrome Screening Should Be Considered for All Patients with Newly Diagnosed Endometrial Cancer. Am J Surg Pathol (2014) 38:1501–9. 10.1097/pas.0000000000000321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hoang LN, Lee Y-S, Karnezis AN, Tessier-Cloutier B, Almandani N, Coatham M, et al. Immunophenotypic Features of Dedifferentiated Endometrial Carcinoma - Insights from BRG1/INI1-Deficient Tumours. Histopathology (2016) 69:560–9. 10.1111/his.12989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kuhn E, Wu R-C, Guan B, Wu G, Zhang J, Wang Y, et al. Identification of Molecular Pathway Aberrations in Uterine Serous Carcinoma by Genome-wide Analyses. J Natl Cancer Inst (2012) 104:1503–13. 10.1093/jnci/djs345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leskela S, Pérez-Mies B, Rosa-Rosa JM, Cristobal E, Biscuola M, Palacios-Berraquero ML, et al. Molecular Basis of Tumor Heterogeneity in Endometrial Carcinosarcoma. Cancers (2019) 11:964. 10.3390/cancers11070964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cuevas D, Velasco A, Vaquero M, Santacana M, Gatius S, Eritja N, et al. Intratumour Heterogeneity in Endometrial Serous Carcinoma Assessed by Targeted Sequencing and Multiplex Ligation‐dependent Probe Amplification: a Descriptive Study. Histopathology (2020) 76:447–60. 10.1111/his.14001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saijo M, Nakamura K, Ida N, Nasu A, Yoshino T, Masuyama H, et al. Histologic Appearance and Immunohistochemistry of DNA Mismatch Repair Protein and P53 in Endometrial Carcinosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol (2019) 43:1493–500. 10.1097/pas.0000000000001353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. De Jong RA, Nijman HW, Wijbrandi TF, Reyners AK, Boezen HM, Hollema H. Molecular Markers and Clinical Behavior of Uterine Carcinosarcomas: Focus on the Epithelial Tumor Component. Mod Pathol (2011) 24:1368–79. 10.1038/modpathol.2011.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rosa-Rosa JM, Leskelä S, Cristóbal-Lana E, Santón A, López-García MÁ, Muñoz G, et al. Molecular Genetic Heterogeneity in Undifferentiated Endometrial Carcinomas. Mod Pathol (2016) 29:1390–8. 10.1038/modpathol.2016.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Coatham M, Li X, Karnezis AN, Hoang LN, Tessier-Cloutier B, Meng B, et al. Concurrent ARID1A and ARID1B Inactivation in Endometrial and Ovarian Dedifferentiated Carcinomas. Mod Pathol (2016) 29:1586–93. 10.1038/modpathol.2016.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zaino RJ, Kurman RJ, Diana KL, Paul Morrow C. The Utility of the Revised International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Histologic Grading of Endometrial Adenocarcinoma Using a Defined Nuclear Grading System. A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Cancer (1995) 75:812–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. León-Castillo A, Gilvazquez E, Nout R, Smit VT, McAlpine JN, McConechy M, et al. Clinicopathological and Molecular Characterisation of ‘multiple-Classifier' Endometrial Carcinomas. J Pathol (2020) 250:312–22. 10.1002/path.5373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang L, Piskorz A, Bosse T, Jimenez-Linan M, Rous B, Gilks CB, et al. Immunohistochemistry and Next-Generation Sequencing Are Complementary Tests in Identifying PTEN Abnormality in Endometrial Carcinoma Biopsies. Int J Gynecol Pathol (2021). 10.1097/pgp.0000000000000763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tashiro H, Blazes MS, Wu R, Cho KR, Bose S, Wang SI, et al. Mutations in PTEN Are Frequent in Endometrial Carcinoma but Rare in Other Common Gynecological Malignancies. Cancer Res (1997) 57:3935–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Risinger JI, Hayes K, Maxwell GL, Carney ME, Dodge RK, Barrett JC, et al. PTEN Mutation in Endometrial Cancers Is Associated with Favorable Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics. Clin Cancer Res (1998) 4:3005–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sun H, Enomoto T, Fujita M, Wada H, Yoshino K, Ozaki K, et al. Mutational Analysis of thePTENGene in Endometrial Carcinoma and Hyperplasia. Am J Clin Pathol (2001) 115:32–8. 10.1309/7jx6-b9u9-3p0r-eqny [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rudd ML, Price JC, Fogoros S, Godwin AK, Sgroi DC, Merino MJ, et al. A Unique Spectrum of Somatic PIK3CA (P110α) Mutations within Primary Endometrial Carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res (2011) 17:1331–40. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-10-0540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Goebel EA, Vidal A, Matias-Guiu X, Blake Gilks C. The Evolution of Endometrial Carcinoma Classification through Application of Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Diagnostics: Past, Present and Future. Virchows Arch (2018) 472:885–96. 10.1007/s00428-017-2279-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Maiques O, Santacana M, Valls J, Pallares J, Mirantes C, Gatius S, et al. Optimal Protocol for PTEN Immunostaining; Role of Analytical and Preanalytical Variables in PTEN Staining in normal and Neoplastic Endometrial, Breast, and Prostatic Tissues. Hum Pathol (2014) 45:522–32. 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Church JM. Polymerase Proofreading-Associated Polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum (2014) 57:396–7. 10.1097/dcr.0000000000000084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wong A, Kuick CH, Wong WL, Tham JM, Mansor S, Loh E, et al. Mutation Spectrum of POLE and POLD1 Mutations in South East Asian Women Presenting with Grade 3 Endometrioid Endometrial Carcinomas. Gynecol Oncol (2016) 141:113–20. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cree IA, Malpica A, McCluggage WG. Neuroendocrine Neoplasia. In: The WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial boardFemale Genital Tumours. 5th ed. Lyon: IARC; (2020). p. 451–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Espinosa I, De Leo A, D'Angelo E, Rosa-Rosa JM, Corominas M, Gonzalez A, et al. Dedifferentiated Endometrial Carcinomas with Neuroendocrine Features: a Clinicopathologic, Immunohistochemical, and Molecular Genetic Study. Hum Pathol (2018) 72:100–6. 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Howitt BE, Dong F, Vivero M, Shah V, Lindeman N, Schoolmeester JK, et al. Molecular Characterization of Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Endometrium. Am J Surg Pathol (2020) 44:1541–8. 10.1097/pas.0000000000001560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.