Abstract

Purpose:

We examined the demographic and clinicopathological parameters associated with the time to convert from active surveillance to treatment among men with prostate cancer.

Materials and Methods:

A multi-institutional cohort of 7,279 patients managed with active surveillance had data and biospecimens collected for germline genetic analyses.

Results:

Of 6,775 men included in the analysis, 2,260 (33.4%) converted to treatment at a median followup of 6.7 years. Earlier conversion was associated with higher Gleason grade groups (GG2 vs GG1 adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.57, 95% CI 1.36–1.82; ≥GG3 vs GG1 aHR 1.77, 95% CI 1.29–2.43), serum prostate specific antigen concentrations (aHR per 5 ng/ml increment 1.18, 95% CI 1.11–1.25), tumor stages (cT2 vs cT1 aHR 1.58, 95% CI 1.41–1.77; ≥cT3 vs cT1 aHR 4.36, 95% CI 3.19–5.96) and number of cancerous biopsy cores (3 vs 1–2 cores aHR 1.59, 95% CI 1.37–1.84; ≥4 vs 1–2 cores aHR 3.29, 95% CI 2.94–3.69), and younger age (age continuous per 5-year increase aHR 0.96, 95% CI 0.93–0.99). Patients with high-volume GG1 tumors had a shorter interval to conversion than those with low-volume GG1 tumors and behaved like the higher-risk patients. We found no significant association between the time to conversion and self-reported race or genetic ancestry.

Conclusions:

A shorter time to conversion from active surveillance to treatment was associated with higher-risk clinicopathological tumor features. Furthermore, patients with high-volume GG1 tumors behaved similarly to those with intermediate and high-risk tumors. An exploratory analysis of self-reported race and genetic ancestry revealed no association with the time to conversion.

Keywords: prostatic neoplasms, watchful waiting, race factors, human genetics

INTRODUCTION

THE preferred management of patients with lower-risk prostate cancer (PC) has evolved to active surveillance (AS) to reduce the morbidity and mortality of overtreatment of indolent disease.1 There are limited published data on the associations of demographic and clinicopathological parameters with the time to converting from AS to treatment.2-9 Conflicting results have been reported on AS outcomes among different racial groups.6,10-19 The literature suggests Black men generally harbor more aggressive tumors with worse clinical outcomes and may be managed with AS less frequently in clinical practice.10,11,13,16,18,20 Yet some studies have reported similar risks for adverse outcomes on AS for Black and White patients with comparable tumor features.6,19 In this cohort study, we assessed the parameters associated with the time to conversion from AS to treatment and undertook an exploratory analysis of the self-reported race and genetic ancestry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A detailed description of the Methods is shown in supplementary Appendix 1 (https://www.jurology.com).

Study Population

This study is an institutional review board-approved (IRB No. STU00077147) Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) project. We evaluated the association of germline genetic variants to conversion from AS to treatment for PC among 7,279 patients at 28 institutions (1991–2018) in a genome-wide association study. Some sites used the terms “AS” and “watchful waiting” interchangeably (supplementary Appendix 1, https://www.jurology.com). As we did not impose strict inclusion/exclusion criteria on patient eligibility for AS, the surveillance protocols used varied among institutions.1,21

Risk Groups and Definitions

Patients were classified into low, intermediate or high-risk groups based on our modification of previous and current National Comprehensive Cancer Network® and the American Urological Association guidelines (supplementary Appendix 1, https://www.jurology.com).1,12,22 Data on prostate specific antigen (PSA) density and clinical tumor stage (cT2a vs cT2b vs cT2c) were not uniformly available, limiting our ability to assign patients to risk strata incorporating those parameters.

Low-risk patients met the following criteria: Gleason grade group (GG) 1 (Gleason score 3+3), PSA <10 ng/ml, clinical-stage cT1, and <3 positive biopsy cores. Intermediate-risk patients had any of the following without any high-risk or high-volume criteria: GG2 (Gleason 3+4), PSA 10–20 ng/ml, stage cT2 or 3 positive biopsy cores of any Gleason grade. High-risk patients had any of the following: ≥GG3 (≥Gleason 4+3), PSA ≥20 ng/ml, stage ≥cT3 or ≥4 positive biopsy cores of any GG. We included patients with cribriform morphology or intraductal carcinoma. In a subgroup analysis, we also compared low-volume GG1, high-volume (≥4 biopsy cores involved) GG1, intermediate-risk and high-risk patients.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the time from PC diagnosis to the time to conversion to treatment. Patients who were followed without a strict AS protocol were analyzed in the same manner as those on AS.

Statistical Analyses

A detailed description of our statistical analysis methods is presented in supplementary Appendix 2 (https://www.iurology.com).23,24 Briefly, variables examined for the association with the time to conversion were summarized using the median and interquartile range for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. For each patient, the time to conversion was calculated from the date of diagnosis until the date of starting treatment. Patients who died during followup or were on AS at the end of followup were treated as censored observations at the time of death or their last followup, respectively. We estimated the distribution for the time to conversion using Kaplan-Meier curves and calculated the median followup time using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method.23 We assessed whether the time to conversion was associated with the demographic or clinicopathological factors in Cox proportional hazards models. We also performed an exploratory subgroup analysis of the self-reported race and genetically inferred ancestry with time to conversion. We used the ADMIXTURE software program (University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin) to model genetic ancestry from our patient data of uncorrelated single nucleotide polymorphisms, in addition to reference data from the 1000 Genome Project for ancestry populations (supplementary Appendix 2, https://www.jurology.com).24

RESULTS

Study Participants

The characteristics of the 6,775 men meeting the inclusion criteria are shown in table 1. Those who were included and excluded from the analysis are shown in supplementary tables 1 and 2 (https://www.jurology.com). Classification as low-risk PC (4,604, 68.0%) and/or low-risk features were most common: GG1 (6,207, 91.6%), tumor stage cT1 (5,387, 79.5%), 1–2 positive biopsy cores (5,260, 77.6%) and a median PSA of 5.0 ng/ml (IQR 3.7–6.7). However, 882 men (13.0%) met our high-risk criteria: ≥GG3 (81, 1.2%), ≥cT3 (48, 0.7%) or ≥4 positive cores of any GG (768, 11.3%). Of the high-risk patients, 360 had ≥4 cores of GG1 with all other features being low risk. Black patients had higher proportions of intermediate and high-risk disease (13.8%) compared to White patients (11.8%; p value for chi-square test= 0.044; supplementary table 3, https://www.jurology.com).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 6,775 patients at active surveillance enrollment

| Median yrs age (IQR) | 64.0 (58.0, 68.2) | |

| No. race (%): | ||

| White | 4,831 | (71.3) |

| Black | 377 | (5.6) |

| Asian | 159 | (2.3) |

| Unknown/underrepresented* | 1,408 | (20.8) |

| No. genetic ancestry (%):† | ||

| European | 5,223 | (77.1) |

| African | 396 | (5.8) |

| East Asian | 156 | (2.3) |

| South Asian | 81 | (1.2) |

| Admixed | 81 | (1.2) |

| No. Gleason GG (%): | ||

| 1 | 6,207 | (91.6) |

| 2 | 482 | (7.1) |

| ≥3 | 81 | (1.2) |

| Median ng/ml PSA at diagnosis (IQR) | 5.0 | (3.7, 6.7) |

| No. tumor stage (%):† | ||

| T1 | 5,387 | (79.5) |

| T2 | 870 | (12.8) |

| T3 or T4 | 48 | (0.7) |

| No. pos cores (%):† | ||

| 1–2 | 5,260 | (77.6) |

| 3 | 581 | (8.6) |

| >4 | 768 | (11.3) |

| No. risk classification (%): | ||

| Low risk | 4,604 | (68.0) |

| Intermediate risk | 1,288 | (19.0) |

| High risk | 882 | (13.0) |

| No. family history of PC (%):† | ||

| No | 4,381 | (64.7) |

| Yes | 1,630 | (24.1) |

| Median diagnosis yr (IQR) | 2011 (2009, 2014) | |

| No. country (%): | ||

| U.S. | 5,138 | (75.8) |

| Canada | 1,470 | (21.7) |

| Netherlands | 133 | (2.0) |

| Australia | 34 | (0.5) |

Baseline characteristics were missing for following proportion of study participants: age at diagnosis, <0.1%; self-reported race, 20.5%; genetic ancestry, 12.4%; Gleason GG, <0.1%; PSA concentration, 3.3%; clinical tumor stage, 6.9%; number of positive biopsy cores, 2.5%; risk group classification, <0.1%; family history of PC, 11%.

Unknown: 1,390 (20.5%). “Underrepresented” includes American Indian/Alaska Native (10; <1%) and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (8; <1%).

Percentages do not sum to 100% due to missing data.

Clinical Outcomes

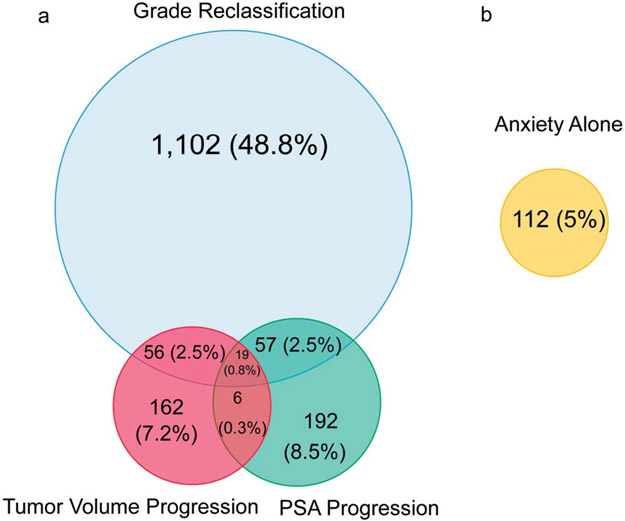

The median followup time for the entire cohort was 6.7 years (IQR 4.3–9.4), during which 2,260 of 6,775 men (33.4%) converted to treatment. In the overall cohort, the median time to conversion was 6.8, 6.1, and 7.0 years for low, intermediate and high-risk/high-volume disease, respectively. Figure 1 shows the reasons for conversion. The most common reason for conversion was grade reclassification alone (48.8%), followed by PSA progression (8.5%), tumor volume progression (7.2%), anxiety (5.0%) and other reasons (9.0%). Of the men who died, 11 (<1%) died of PC, while 91 (1.3%) died of a competing cause.

Figure 1.

Scaled Venn diagram shows reason for conversion to treatment including grade reclassification, tumor volume progression and/or PSA progression (a), and anxiety alone without other reasons (b). Percentages are out of total number of men who converted (2,260). Overlap between anxiety with other reasons for conversion: grade reclassification, 5 (0.2%); tumor volume progression, 0; PSA progression, 6 (0.3%).

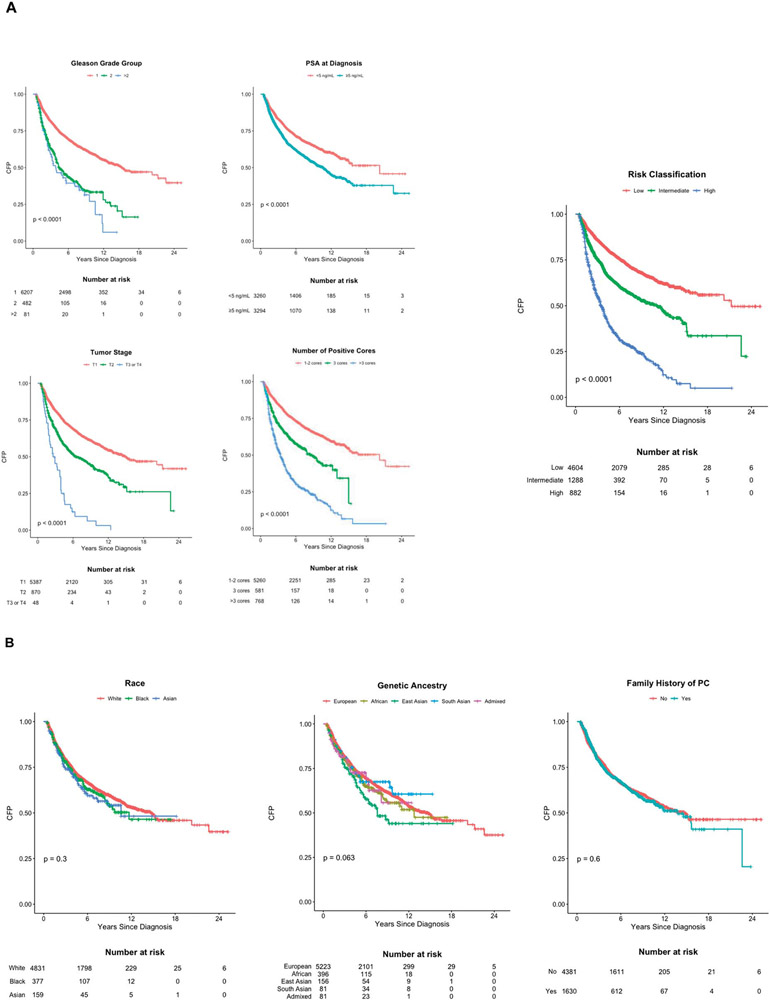

Associations with Conversion to Treatment

In univariable analysis, higher GG, serum PSA, clinical tumor stage, number of positive biopsy cores, risk-group classification and more recent year of diagnosis were significantly associated with a shorter time to conversion (table 2 and fig. 2, A). The multivariable model included age at diagnosis, GG, PSA, tumor stage, number of positive biopsy cores and year of diagnosis, and was stratified on self-reported race categories. Higher GG, PSA, clinical tumor stage, number of positive biopsy cores and more recent year of diagnosis were significantly associated with earlier time to conversion (table 2). Additional sensitivity analyses with grade reclassification or grade or volume reclassification as the sole outcome, although limited by statistical power, also revealed trends for an association with these same 5 parameters with time to conversion (supplementary tables 4 and 5, https://www.jurology.com).

Table 2.

Associations between demographic and clinical characteristics and time to conversion to treatment among 6,775 men with prostate cancer

| Univariable Models |

Multivariable Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. Events | HR | 95% CI | p Value | aHR* | 95% CI | p Value |

| Age category: | 0.3 for trend | ||||||

| ≤50 yrs | 99 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| 51–60 yrs | 641 | 0.94 | 0.76, 1.16 | 0.6 | |||

| 61–70 yrs | 1,156 | 1.06 | 0.86, 1.30 | 0.6 | |||

| >70 yrs | 364 | 0.98 | 0.78, 1.22 | 0.8 | |||

| Age continuous per 5-yr increase | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.04 | 0.3 | 0.96 | 0.93, 0.99 | 0.006 | |

| Race: | |||||||

| White | 1,604 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Black | 126 | 1.10 | 0.92, 1.32 | 0.3 | |||

| Asian | 58 | 1.18 | 0.91, 1.53 | 0.2 | |||

| Genetic ancestry: | |||||||

| European | 1,659 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| African | 125 | 1.12 | 0.93, 1.34 | 0.2 | |||

| East Asian | 66 | 1.41 | 1.10, 1.80 | 0.007 | |||

| South Asian | 26 | 0.94 | 0.64, 1.38 | 0.8 | |||

| Admixed | 23 | 1.11 | 0.73, 1.67 | 0.6 | |||

| Gleason GG: | <0.001 for trend | <0.001 for trend | |||||

| 1 | 1,952 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| 2 | 255 | 2.22 | 1.95, 2.53 | <0.001 | 1.57 | 1.36, 1.82 | <0.001 |

| ≥3 | 51 | 2.63 | 1.99, 3.47 | <0.001 | 1.77 | 1.29, 2.43 | <0.001 |

| Median PSA at diagnosis: | |||||||

| <5 ng/ml | 950 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| ≥ 5 ng/ml | 1,231 | 1.44 | 1.35, 1.59 | <0.001 | |||

| PSA at diagnosis, continuous | 1.25 | 1.19, 1.32 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.11, 1.25 | <0.001 | |

| per 5 ng/ml increase | |||||||

| Tumor stage: | <0.001 for trend | <0.001 for trend | |||||

| T1 | 1,706 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| T2 | 415 | 1.75 | 1.57, 1.95 | <0.001 | 1.58 | 1.41, 1.77 | <0.001 |

| T3 or T4 | 44 | 4.64 | 3.43, 6.26 | <0.001 | 4.36 | 3.19, 5.96 | <0.001 |

| No. pos cores: | <0.001 for trend | <0.001 for trend | |||||

| 1–2 | 1,463 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| 3 | 234 | 1.82 | 1.59, 2.09 | <0.001 | 1.59 | 1.37, 1.84 | <0.001 |

| ≥4 | 502 | 3.67 | 3.31, 4.06 | <0.001 | 3.29 | 2.94, 3.69 | <0.001 |

| Risk classification: | <0.001 for trend | ||||||

| Low risk | 1,195 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Intermediate risk | 493 | 1.75 | 1.57, 1.94 | <0.001 | |||

| High risk, high vol | 572 | 3.92 | 3.55, 4.34 | <0.001 | |||

| Family history of PC: | |||||||

| No | 1,439 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 548 | 1.03 | 0.93, 1.13 | 0.6 | |||

| Median diagnosis yr: | |||||||

| 1991–2010 | 1,006 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| 2011–2018 | 1,254 | 1.44 | 1.32, 1.57 | <0.001 | |||

| Diagnosis yr, continuous per 5-yr increase | 1.38 | 1.30, 1.47 | <0.001 | 1.43 | 1.33, 1.53 | <0.001 | |

| Country: | |||||||

| U.S. | 1,623 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Canada | 561 | 0.98 | 0.89, 1.08 | 0.7 | |||

| Netherlands | 42 | 0.84 | 0.62, 1.14 | 0.3 | |||

| Australia | 34 | 9.62 | 6.84, 13.5 | <0.001 | |||

Variables are mutually adjusted and hazard ratios are summarized across race strata. Characteristics with empty HRs are not included as model covariates.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of time to conversion to treatment by patient demographic and cancer clinical factors. A, Kaplan-Meier plots of prostate cancer clinical variables in relation to time to conversion. P value is reported from log-rank test. B, Kaplan-Meier plots of race, genetic ancestry and family history of prostate cancer in relation to time to conversion. P value is reported from log-rank test. CFP, conversion-free probability.

In an exploratory analysis, men with ≥4 GG1 cores were more likely than those with ≤3 GG1 cores to convert to treatment (63.6% vs 26.0%) with a 5-year conversion-free probability of 35.8% vs 78.6%. Conversion rates were similar between high-volume GG1 patients and other high-risk patients (63.6% vs 65.7%, with a 5-year conversion-free probability of 35.8% vs 38.0%) and higher than those with intermediate-risk disease (38.3% converted with 64.1% 5-year conversion-free probability; supplementary table 6, https://www.jurology.com). Similarly in a multivariable model, high-volume GG1 patients converted to treatment sooner than low-volume, GG1 patients (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 3.46, 95% CI 2.92–4.10), and their risk for conversion was higher than for intermediate-risk patients (aHR 1.78, 95% CI 1.59–1.99) and similar to all other high-risk patients (aHR 4.00 95% CI 3.48–4.59; supplementary table 7, https://www.jurology.com).

Our study required germline DNA for genetic analyses; however, patients from UCSF (University of California, San Francisco) and Australia collected samples only from the patients who had undergone prostatectomy. Removing these patients from the analysis, 2,004 of the 6,519 men (30.7%) converted to treatment. As this could introduce a selection bias, we undertook a separate sensitivity analysis including and excluding them. Excluding them did not change the results (supplementary table 8, https://www.jurology.com).

Parameters Not Associated with Conversion to Treatment

Neither age nor a positive family history of PC was associated with the time to conversion in univariable analysis (table 2, fig. 2, B and supplementary tables 4, 5 and 7 to 9, https://www.jurology.com). However, in the multivariable model, increasing age was associated with longer time on AS (table 2). Family history was not included in the multivariable model because data were missing for 11% of the patients. The time to conversion did not differ for patients from different countries, and a sensitivity analysis that excluded the Australia and UCSF sites did not affect the associations for the other variables (supplementary table 8, https://www.jurology.com).

Adjusted HRs for the self-reported race could not be estimated directly because the proportional hazards assumption was not satisfied when including men whose race was unknown or underrepresented. Excluding these men allowed the calculation of an aHR for race, and no significant association was observed in the multivariable model (supplementary table 8, https://www.jurology.com). Furthermore, there was no difference in the time to conversion between Black and White men across risk group strata (fig. 2, B, supplementary table 8 and supplementary fig. 1, https://www.jurology.com).

In the exploratory analysis of genetic ancestry, 121 of 141 men who self-reported Asian (85.8%) were estimated to be of Asian ancestry, 292/315 of Black men (92.7%) were estimated to be of African ancestry and 4,079/4,152 of White men (98.2%) were estimated to be of European ancestry. No genetic ancestry group had a significantly earlier time to conversion (fig. 2, B, table 2, supplementary tables 9 and 10, and supplementary fig. 2, https://www.jurology.com).

Outcomes following Treatment

Of the 2,260 men who converted to treatment (1,107 prostatectomy, 565 radiotherapy and 588 other treatments), 124 (5.5%) subsequently developed a PSA recurrence, 29 (1.3%) developed metastasis and 11 (<1%) died of PC.

DISCUSSION

Our study is the largest non-VA study to assess the time to conversion from AS to treatment. Unlike most of the AS studies that used strict enrollment criteria, ours is more risk-inclusive, more accurately reflecting real-world practice patterns.2-5,7-9 The clinicopathological variables associated with earlier time to conversion to treatment were higher GG, serum PSA level, clinical stage, number of cancerous biopsy cores, age, and risk-group classification. These findings mirror the results of prior studies in men on AS who met stricter enrollment criteria.2-5,7-9,25,26 Despite our cohort including a larger proportion of high-risk patients, adverse outcomes were uncommon during our limited followup (median 6.7 years for the entire cohort). High-volume (≥4 cores) GG1 patients converted to treatment sooner than their low-volume (≤3 cores) and intermediate-risk tumor counterparts but at a similar interval to patients with high-risk tumors (supplementary tables 6 and 7, https://www.jurology.com). This finding warrants future investigation regarding tumor biology and counseling of men with high-volume GG1 disease.

Previous studies have reported that Black men have more biologically aggressive PC, a higher risk of grade reclassification or adverse surgical pathology after initial AS and are more likely than White men to die of PC.10,11,15,16,18,20 AS outcomes in Black men have been difficult to interpret because of small sample sizes and uncertainty as to the extent to which the reported differences were due to health care disparities.6,13,14 The largest studies reported to date comparing Black and White men on AS are from the Veterans Administration database. These studies reported that Black men had an increased risk for disease progression, a greater likelihood to receive definitive treatment and converted to treatment at an earlier time than White men.13,14 Our exploratory analysis of the self-reported race bolstered by the genetic ancestry markers found no significant difference between Black and White men, which adds substantially to the literature on this issue (fig. 2, B, supplementary tables 3 and 9 to 11, and supplementary figs. 1 and 2, https://www.jurology.com).

Unlike a previous report, we found no association of the time to conversion with a family history of PC.26 Similarly, patients diagnosed during the more recent years (2014–2018) had a shorter time on AS, which likely reflects the more recent adoption of more liberal AS eligibility criteria (supplementary Appendix 2, https://www.jurology.com).27

The study has several limitations, including the lack of data on PSA density, biopsy-based genomic biomarkers and multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging.28 At the start of our study, these parameters were not commonly utilized, and there was more variability in the interpretation of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging among radiologists.29 Second, the study lacks data on comorbidities, interval PSA values, and confirmatory and surveillance biopsies that would have rendered interpretation of the outcomes more granular. The extent to which these limitations affect the findings is unknown.

Despite these limitations, our study adds quantification as to the degree to which demographic and clinicopathological parameters are associated with the time to conversion to treatment across a broad spectrum of risk groups, especially among high-risk and high-volume GG1 patients. Furthermore, we mitigated the intrinsic limitations of studying self-reported race by including genetic ancestry. These topics need to be further explored over a longer followup period.

CONCLUSIONS

Approximately a third of patients in a large multi-institutional cohort managed with AS converted to treatment with a median followup of 6.7 years. The time to conversion was independently associated with the age, year of diagnosis, GG group, serum PSA level, clinical stage and the number of cancerous biopsy cores. The risk of conversion for patients with high-volume GG1 tumors was higher than for low and intermediate-risk patients and approached the patterns seen in high-risk patients. An exploratory analysis of patient-reported race and genetic ancestry revealed no difference between Black and White patients for the time to conversion to treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge Julia T. Arnold, PhD, Tamara Walton, MPA, MHA, Melissa Rotunno, PhD, Barbara Thomas, PhD, and the Center for Inherited Disease Research Staff for their invaluable assistance with this project.

Funding/Support and Role of the Sponsor: P50CA180995 (Catalona) 08/01/15–07/31/21 NIH/NCI SPORE in Prostate Cancer PI on the SPORE grant, Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR) award from the NCI for patient sample genotyping (X01HG009642), Urological Research Foundation (Catalona), NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, Illinois (Helfand). Additional support was provided by award numbers R01CA158627 and R01CA195505 (Marks), P50 CA186786 (Morgan), UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NIH for Vanderbilt REDCap (Barocas), P50 CA097186 and K05 CA175147 (Stanford), and U01 CA113913 (Sanda) from the National Institute of Health.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- aHR

adjusted hazard ratio

- AS

active surveillance

- GG

grade group

- PC

prostate cancer

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

Appendix

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Cooley, Emeka, Catalona, Lancki, Helfand, Meyers, Witte, Scholtens; Acquisition of data: Emeka, Cooper, Lancki, Catalona, Scholtens, Helfand, Lin, Stanford, Newcomb, Colb, Finelli, Komisarenko, Eastham, Ehdaie, Benfante, Logothetis, Gregg, Perez, Garza, Marks, Barsa, Vesprini, Mamedov, Goldenberg, Higano, Arvoska, Wu, Pavlovich, Mamawala, Carroll, Chan, Morgan, Siddiqui, Martin, Klein, Gotwald, Barocas, Dallmer, Steele, Kundu, Stockdale, Roobol, Venderbos, Sanda, Patil, Evans, Dall'Era, Vij, Costello, Chow, Rais-Bahrami, Phares, Scherr, Flynn, Karnes, Koch, Dhondt, Nelson, McBride, Cookson, Stratton, Farriester, Hemken, Stadler, Banionyte, Bianco Jr., Lopez, Loeb, Byrne, Amling, Boileau, Gaylis, Kundu; Analysis and interpretation of data: Cooley, Emeka, Meyers, Jiang, Lancki, Catalona, Helfand, Witte, Scholtens; Drafting of the manuscript: Cooley, Emeka, Catalona, Helfand, Meyers, Jiang, Witte, Scholtens; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Cooley, Emeka, Helfand, Catalona, Meyers, Jiang, Witte, Scholtens, Cooper, Lin, Stanford, Finelli, Eastham, Ehdaie, Logothetis, Gregg, Marks, Vesprini, Loblaw, Klotz, Kundu, Goldenberg, Higano, Pavlovich, Caroll, Cooperberg, Chan, Morgan, Klein, Barocas, Roobol, Sanda, Evans, Dall'Era, Costello, Chow, Rais-Bahrami, Scherr, Karnes, Koch, Nelson, Cookson, Stratton, Stadler, Bianco Jr., Loeb, Amling, Cooperberg, Gaylis; Final approval of the version to be published: Cooley, Emeka, Helfand, Catalona, Meyers, Jiang, Witte, Scholtens, Cooper, Lin, Stanford, Finelli, Eastham, Ehdaie, Logothetis, Gregg, Marks, Vesprini, Loblaw, Klotz, Kundu, Goldenberg, Higano, Pavlovich, Caroll, Cooperberg, Chan, Morgan, Klein, Barocas, Roobol, Sanda, Evans, Dall'Era, Costello, Chow, Rais-Bahrami, Scherr, Karnes, Koch, Nelson, Cookson, Stratton, Stadler, Bianco Jr., Loeb, Amling, Cooperberg, Gaylis; Author accountability: Cooley, Emeka, Helfand, Catalona, Meyers, Jiang, Witte, Scholtens, Cooper, Lin, Stanford, Finelli, Eastham, Ehdaie, Logothetis, Gregg, Marks, Vesprini, Loblaw, Klotz, Kundu, Goldenberg, Higano, Pavlovich, Caroll, Cooperberg, Chan, Morgan, Klein, Barocas, Roobol, Sanda, Evans, Dall'Era, Costello, Chow, Rais-Bahrami, Scherr, Karnes, Koch, Nelson, Cookson, Stratton, Stadler, Bianco Jr., Loeb, Amling, Cooperberg, Gaylis take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; Statistical analysis: Meyers, Lancki, Jiang, Witte, Xu, Scholtens; Acquisition of funding: Catalona, Witte, Helfand.

Contributor Names: Laurence H. Klotz1; H. Ballentine Carter2; Peter R. Carroll3; Neil E. Fleshner4; Monique J. Roobol5; Martin G. Sanda6; Christopher P. Evans7; Marc A. Dall'Era7; Janet L. Stanford8,9; Lisa F. Newcomb10,11; R. Jeffrey Karnes14; Franklin D. Gaylis15; Shilajit D. Kundu16; Michael Koch17; Joel B. Nelson18; Michael S. Cookson19; Douglas S. Scherr20; Fernando J. Bianco, Jr.21; Christopher L. Amling22; Anthony J. Costello23; Ken Chow23; Samir S. Taneja13; Niall M. Corcoran23; Matthew R. Cooperberg3,24; Justin R. Gregg25; Andrew Loblaw1; Walter M. Stadler26; Behfar Ehdaie27; Yu Jiang28; Kelly L. Stratton19; Soroush Rais-Bahrami29; Jeremiah R. Dallmer30,31; Jennifer B. Gordetsky30,32; Jeri Kim33; Jianfeng Xu34; Thomas Flynn20; Merdie Delfin35; Mufaddal Mamawala2; Isabel H. Lopez21; Janet E. Cowan36; Lionne D.F. Venderbos5; Rebecca Arnold6; Dattatraya Patil6; Javed Siddiqui37; Irene Helenowski38; Nicola Lancki38; Suzanne Kolb8,9; Maria Komisarenko4; Nicole Benfante27; Cherie A. Perez25; Sergio Garz25; Danielle Barsa35; Alexandre Mamedov1; Jacqueline Petkewicz34; Nicholas Kirwen34; Olga Arsovska12; Eugenia Wu12; Tricia Landis2; Rabia Martin39; Karen Brittain40; Paige Gotwald40; Pam Steele30; Jazmine Stockdale16; Anjali Vij7; Courtney Phares29; Courtney Rose Dhondt17; Dawn McBride18; Stephen Farriester19; Erin Hemken19; Tuula Pera26; Deimante Banionyte26; Nataliya Byrne13; Ann Martinez22; Luc Boileau22; the Prostate Cancer Foundation in Rotterdam, the Canary Prostate Active Surveillance Study (PASS).

Contributor Affiliations:1Odette Cancer Centre, Sunnybrook Health and Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; 2The Brady Urological Institute, the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland; 3Department of Urology, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California; 4Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; 5Department of Urology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; 6Department of Urology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia; 7Department of Urologic Surgery, University of California, Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, California; 8Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Cancer Epidemiology Program, Public Health Sciences, Seattle, Washington; 9Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington; 10Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Cancer Prevention Program, Public Health Sciences, Seattle, Washington; 11Department of Urology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington; 12Department of Urologic Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 13Departments of Urology and Population Health, New York University Langone Health and Manhattan Veterans Affairs Medical Center, New York, New York; 14Mayo Clinic Department of Urology, Rochester, Minnesota; 15Genesis Healthcare Partners, Department of Urology, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California; 16Department of Urology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IllinoisL; 17Department of Urology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN; 18Department of Urology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 19Department of Urology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; 20Department of Urology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, New York; 21Urological Research Network, Miami Lakes, Florida; 22Department of Urology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon; 23Department of Urology, Royal Melbourne Hospital and University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; 24Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California; 25Departments of Genitourinary Medical Oncology and Urology, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas; 26University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center, Chicago, Illinois; 27Urology Service, Department of Surgery, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York; 28Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California; 29Department of Urology, the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama; 30Department of Urology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; 31Department of Urology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California; 32Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; 33Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey; 34Division of Urology, NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, Illinois; 35Department of Urology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, California; 36Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California; 37Department of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; 38Division of Biostatistics, Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois; 39Department of Urology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; and 40Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

DEDICATION

This study is gratefully dedicated to the memory of Andrew M. Hruszkewycz, MD, PhD, a beloved, respected, and devoted Program Officer of the NCI Translational Research Program and model public servant.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Finelli—Consultant/Advisory Board (Abbvie, Astellas, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Janssen, Sanofi, TerSera). Dr. Fleshner—Honoraria/advisory/speaker bureau (Astellas, Janssen, Abbvie, Ferring, Sanofi, Merck); Research funding (Janssen, Astellas, Bayer); Stock (Verity Pharma). Dr. Eastham—Stock (3D biopsy). Dr. Ehdaie—Consulting (Myriad, Inc); Honorarium (Koelis webinar). Dr. Gregg—Advisory board for Genentech, not related to the manuscript. Dr. Marks—Co-founder (Avenda Health). Dr. Higano—Institutional research funding (Aptevo, Aragon, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Dendreon, eFFECTOR Therapeutics, Emergent, Ferring, Genentech, Hoffman-Laroche, Medivation, Pfizer); Consulting, scientific advisory boards (Astellas, Bayer, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Clovis, Dendreon, Ferring, Hinova, Janssen, Merck, Orion, Pfizer, Tolmar, Carrick Therapeutics, Novartis, Genentech); Other (spouse holds stock and former officer of CTI Biopharma). Dr. Pavlovich—Clinical trial Steering Committee member and clinical trial site Principal Investigator (PI) (Dendreon); clinical trial site PI (Profound Medical, Canada); clinical trial site PI (Nanostics, Canada). Dr. Carroll—advisory board (Nutcracker Therapeutics [messenger RNA therapy], Francis Medical [tissue ablation] and Insightec [tissue ablation]), not relevant to this study. Dr. Cooperberg—reports personal fees from Astellas, Bayer, MDx Health, Myriad Genetics, Dendreon, Steba Biotech, Astra Zeneca and Abbvie, outside the submitted work. Dr. Chan—Husband is a full-time employee of GRAIL, Inc. Dr. Barocas—Advisory Boards for Progenics. Dr. Dall'Era—Clinical trial (Janssen); Grant (Tempus); Speaker (Photocure). Dr. Rais-Bahrami—Consultant (Philips/InVivo Corp, Genomic Health Inc, Bayer Healthcare, Blue Earth Diagnostics and Intuitive Surgical). Research funding support (NIH/NCI, U.S. Department of Defense, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Genomic Health Inc, and Astellas). Dr. Karnes—Institutional and personal IP-royalties (Decipher Biosciences). Dr. Cookson—Advisory Board (Astellas, Janssen, Merck, Bayer). Dr. Stratton—Advisor (Dendreon); Honoraria (Bayer). Dr. Stadler—Consultant (DSMB; Astra-Zeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Merck, Pfizer, Sotio); Consultant (Caremark/CVS, Genentech, Pfizer); Speakers Bureau (CME providers [sponsorship unknown]: Applied Clinical Education, Dava Oncology, Global Academy for Medical Education, OncLive, PeerView, Vindico); Grant/Research Support to institution (Abbvie, Astra-Zeneca, Astellas [Medivation], Bayer, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Calithera, Clovis, Corvus, Eisai, Exilixis, Genentech [Roche], Johnson&Johnson [Janssen], Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Tesaro, X4Pharmaceuticals); Miscellaneous/Editorial (Cancer [ACS], Up-To-Date). Dr. Loeb—has equity in Gilead, unrelated to the current manuscript. Dr. Helfand—Advisory board and speaker (Ambry Genetics); Researcher and speaker (Exact Sciences); Researcher, advisory board and speaker (Blue Earth Diagnostics). Dr. Taneja—Consultant (Trod Medical, Francis Medical, Insightec, Exact Imaging); scientific advisory board (GT Biopharma); scientific investigator (MDxHealth). Dr. Gaylis—scientific advisory board (Stratify Genomics). Dr. Cooley, Dr. Emeka, Dr. Meyers, Dr. Helenowski, Ms. Lancki, Mr. Cooper, Dr. Xu, Dr. Lin, Dr. Stanford, Dr. Newcomb, Dr. Logothetis, Dr. Vesprini, Dr. Klotz, Dr. Loblaw, Dr. Goldenberg, Dr. Carter, Dr. Mamawala, Ms. Cowan, Dr. Morgan, Mr. Siddiqui, Dr. Klein, Dr. Dallmer, Dr. Kundu, Dr. Roobol, Dr. Venderbos, Dr. Sanda, Dr. Arnold, Dr. Patil, Dr. Evans, Prof. Costello, Dr. Chow, Dr. Corcoran, Dr. Gordetsky, Dr. Scherr, Mr. Flynn, Dr. Koch, Dr. Nelson, Dr. Bianco, Ms. Lopez, Dr. Amling, Dr. Scholtens, Dr. Witte, Dr. Catalona declare no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E et al. : Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Part I: Risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J Urol 2018; 199: 683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruinsma SM, Zhang L, Roobol MJ et al. : The Movember Foundation's GAP3 cohort: a profile of the largest global prostate cancer active surveillance database to date. BJU Int 2018; 121: 737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Hemelrijck M, Ji X, Helleman J et al. : Reasons for discontinuing active surveillance: assessment of 21 centres in 12 countries in the Movember GAP3 consortium. Eur Urol 2019; 75: 523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregg JR, Davis JW, Reichard C et al. : Determining clinically based factors associated with reclassification in the pre-MRI era using a large prospective active surveillance cohort. Urology 2020; 138: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komisarenko M, Martin LJ and Finelli A: Active surveillance review: contemporary selection criteria, follow-up, compliance and outcomes. Transl Androl Urol 2018; 7: 243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schenk JM, Newcomb LF, Zheng Y et al. : African American race is not associated with risk of reclassification during active surveillance: results from the Canary Prostate Cancer Active Surveillance Study. J Urol 2020; 203: 727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tosoian JJ, Mamawala M, Epstein JI et al. : Active surveillance of grade group 1 prostate cancer: long-term outcomes from a large prospective cohort. Eur Urol 2020; 77: 675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Makarov DV et al. : Five-year nationwide follow-up study of active surveillance for prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2015; 67: 233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bokhorst LP, Valdagni R, Rannikko A et al. : A decade of active surveillance in the PRIAS study: an update and evaluation of the criteria used to recommend a switch to active treatment. Eur Urol 2016; 70: 954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pienta KJ, Demers R, Hoff M et al. : Effect of age and race on the survival of men with prostate cancer in the Metropolitan Detroit Tricounty area, 1973 to 1987. Urology 1995; 45: 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG et al. : Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA Cancer J Clin 2016; 66: 290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dess RT, Suresh K, Zelefsky MJ et al. : Development and validation of a clinical prognostic stage group system for nonmetastatic prostate cancer using disease-specific mortality results from the international staging collaboration for cancer of the prostate. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6: 1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parikh RB, Robinson KW, Chhatre S et al. : Comparison by race of conservative management for low-risk and intermediate-risk prostate cancers in Veterans from 2004 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e2018318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deka R, Courtney PT, Parsons JK et al. : Association between African American race and clinical outcomes in men treated for low-risk prostate cancer with active surveillance. JAMA 2020; 324: 1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler S, Muralidhar V, Chavez J et al. : Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer in black patients. New Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahal BA, Berman RA, Taplin ME et al. : Prostate cancer-specific mortality across Gleason scores in black vs nonblack men. JAMA 2018; 320: 2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gökce MI, Sundi D, Schaeffer E et al. : Is active surveillance a suitable option for African American men with prostate cancer? A systemic literature review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2017; 20: 127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen X, Pettaway CA and Chen RC: Active surveillance for black men with low-risk prostate cancer. JAMA 2020; 324: 1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dess RT, Hartman HE, Mahal BA et al. : Association of Black race with prostate cancer–specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol 2019; 5: 975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iremashvili V, Soloway MS, Rosenberg DL et al. : Clinical and demographic characteristics associated with prostate cancer progression in patients on active surveillance. J Urol 2012; 187: 1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uroweb: EAU Guidelines: Prostate Cancer. Available at https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/. Accessed September 14, 2020.

- 22.Mohler JL, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ et al. : Prostate cancer, version 2.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019; 17: 479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shuster JJ: Median follow-up in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 1991; 9: 191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander DH, Novembre J and Lange K: Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res 2009; 19: 1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA et al. : 10-Year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. New Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welty CJ, Cowan JE, Nguyen H et al. : Extended followup and risk factors for disease reclassification in a large active surveillance cohort for localized prostate cancer. J Urol 2015; 193: 807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Modi PK, Kaufman SR, Qi J et al. : National trends in active surveillance for prostate cancer: validation of Medicare claims-based algorithms. Urology 2018; 120: 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jayadevan R, Felker ER, Kwan L et al. : Magnetic resonance imaging-guided confirmatory biopsy for initiating active surveillance of prostate cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2: e1911019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonn GA, Fan RE, Ghanouni P et al. : Prostate magnetic resonance imaging interpretation varies substantially across radiologists. Eur Urol Focus 2019; 5: 592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.