Abstract

We examined mutations in the dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) genes of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis (P. carinii) strains isolated from 24 patients with P. carinii pneumonia (PCP) in Japan. DHPS mutations were identified at amino acid positions 55 and/or 57 in isolates from 6 (25.0%) of 24 patients. The underlying diseases for these six patients were human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection (n = 4) or malignant lymphoma (n = 2). This frequency was almost the same as those reported in Denmark and the United States. None of the six patients whose isolates had DHPS mutations were recently exposed to sulfa drugs before they developed the current episode of PCP, suggesting that DHPS mutations not only are selected by the pressure of sulfa agents but may be incidentally acquired. Co-trimoxazole treatment failed more frequently in patients whose isolates had DHPS mutations than in those whose isolates had wild-type DHPS (n = 4 [100%] versus n = 2 [11.1%]; P = 0.002). Our results thus suggest that DHPS mutations may contribute to failures of co-trimoxazole treatment for PCP.

Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis (P. carinii) causes opportunistic pulmonary infection in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 (HIV-1) infection (7). P. carinii pneumonia (PCP) in HIV-infected individuals is an important cause of morbidity and mortality, although the frequency of PCP has decreased with the establishment of highly active antiretroviral therapy (16).

Sulfonamides are key agents for the treatment and prophylaxis of PCP. Co-trimoxazole, which is a combination of two antifolate agents, sulfamethoxazole (sulfonamide) and trimethoprim, is the first choice for the treatment and prophylaxis of PCP (14). Since the antipneumocystosis activity of co-trimoxazole is almost entirely due to sulfamethoxazole (13, 15), co-trimoxazole treatment is virtually sulfamethoxazole monotherapy. Resistance to sufonamides has been reported in numerous pathogens including Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Plasmodium falciparum. A culture system for human P. carinii has recently been described (12). However, whether or not the culture system can be reproduced in multiple laboratories in a standardized fashion is being evaluated, and the system has not yet been established completely.

The target enzyme of sulfonamide is the dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS), which catalyzes the condensation of p-aminobenzoic and 6-hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin pyrophosphate to produce 7,8-dihydropteroate. In Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Plasmodium falciparum, mutations in DHPS genes were found to confer sulfonamide resistance (2, 3, 4, 10). Lane et al. (9) reported DHPS mutations at amino acid positions 23, 55, 57, 60, 111, and 248 in P. carinii under selective pressure with sulfonamide drugs. Of the six mutations, it has been suggested that amino acid substitutions at codons 55 and 57 correlate with resistance to sulfonamides (6, 8, 11). Thus, genotyping of DHPS as well as phenotyping of organism by in vitro culture may be of help with prediction of the sensitivity of P. carinii to sulfonamides and the results of treatment.

Here we report the DHPS amino acid sequence patterns of P. carinii strains isolated from immunosuppressed patients in Japan and discuss the relationship between DHPS mutations and the results of co-trimoxazole treatment in patients with PCP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens and characteristics of patients.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid specimens were used in the study. Up to now BAL rather than the induction of sputum has been applied as the method of choice for the diagnosis of PCP because the use of inducted sputum may result in false-negative results. After diagnostic examinations including staining for P. carinii were completed, BAL fluid was centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min and the pellet was stored at −80°C until use. Twenty-four specimens were collected from April 1994 to September 1999 in two hospitals in Tokyo (the Institute of Medical Science Hospital, University of Tokyo, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Bokutoh General Hospital). The patients' characteristics are shown in Table 1. The underlying diseases for the patients included HIV-1 infection (n = 16), malignant lymphoma (n = 3), post-kidney transplantation state (n = 2), rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (n = 1), polyarteritis (n = 1), and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (n = 1). The numbers of CD4-positive lymphocytes at the time of specimen collection were below 200/mm3 for all patients for whom they were determined. Five patients were given intravenous or aerosolized pentamidine for PCP prophylaxis. Three cases (patient 5, 6, and 9) had prior episodes of PCP. No patients had taken or were taking sulfadiazine as therapy and suppression for toxoplasmosis.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Patient no. | Age (yr) | Sexa | Underlying disease | CD4+-cell count (no./mm3) | PCP prophylaxis

|

Frequency of PCP episodes | Date of specimen collection (mo/day/yr) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-trimoxazole | Pentamidine | |||||||

| 1 | 56 | M | HIV infection | 58 | − | − | 1 | 4/14/1994 |

| 2 | 27 | M | HIV infection | 66 | − | − | 1 | 8/17/1995 |

| 3 | 31 | M | HIV infection | 123 | − | − | 1 | 4/8/1997 |

| 4 | 53 | M | HIV infection | 18 | − | − | 1 | 4/11/1997 |

| 5 | 27 | M | HIV infection | 7 | − | + | 2 | 6/6/1997 |

| 6 | 28 | M | HIV infection | 12 | − | + | 4 | 6/17/1997 |

| 7 | 55 | M | HIV infection | 24 | − | − | 1 | 8/21/1997 |

| 8 | 52 | M | HIV infection | 99 | − | − | 1 | 9/12/1997 |

| 9 | 32 | M | HIV infection | 18 | − | + | 2 | 9/26/1997 |

| 10 | 55 | M | HIV infection | 98 | − | + | 1 | 11/21/1997 |

| 11 | 56 | M | HIV infection | 197 | − | − | 1 | 5/1/1998 |

| 12 | 39 | M | HIV infection | 2 | − | − | 1 | 11/4/1998 |

| 13 | 52 | M | HIV infection | 55 | − | − | 1 | 6/24/1999 |

| 14 | 38 | M | HIV infection | 38 | − | − | 1 | 7/2/1999 |

| 15 | 49 | F | HIV infection | 43 | − | − | 1 | 9/6/1999 |

| 16 | 41 | M | HIV infection | 17 | − | − | 1 | 9/22/1999 |

| 17 | 45 | M | Lymphoma | 24 | − | − | 1 | 5/7/1997 |

| 18 | 58 | F | Lymphoma | 164 | − | + | 1 | 7/24/1997 |

| 19 | 66 | F | Renal transplant | 93 | − | − | 1 | 1/16/1998 |

| 20 | 50 | M | Lymphoma | 146 | − | − | 1 | 4/16/1998 |

| 21 | 62 | M | RPGNb | 210c | − | − | 1 | 7/31/1998 |

| 22 | 77 | M | Polyangitis | 228c | − | − | 1 | 8/14/1998 |

| 23 | 65 | M | LIPd | 385c | − | − | 1 | 9/29/1998 |

| 24 | 51 | M | Renal transplant | 206c | − | − | 1 | 2/2/1999 |

M, male; F, female.

RPGN, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

Total lymphocyte counts (number of lymphocytes per cubic millimeter).

LIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia.

PCR.

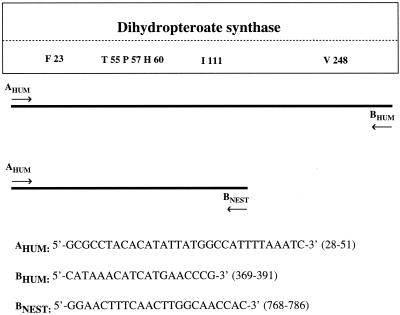

The pellet obtained after centrifugation of BAL fluid was resuspended in 100 μl of saline, and the DNA was extracted with SMI TEST EX-R&D (Sumitomo Metal Ind. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The PCR mixture contained template DNA, PCR buffer, 0.2 μM (each) PCR primer (AHUM and BHUM; see Fig. 1), 0.2 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2.5 U of Ex-Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Shiga, Japan) in a total volume of 100 μl. After initial denaturation for 2 min at 94°C, 35 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 1 min), annealing (45°C, 1 min), and extension (72°C, 2 min) were performed. The reaction mixture was kept at 72°C for 10 min for final extension. In order to avoid contamination of the PCR mixtures, mixture preparation and template DNA addition were done in separate rooms. A negative control without template DNA was always included. The PCR products were electrophoresed through a 1.2% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml, and bands of the expected size (750 bp) were visualized with UV light, excised, and purified with a gel extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) by following the manufacturer's instructions.

FIG. 1.

DHPS and PCR primers used in this study. Amino acids (one-letter code) in a box indicate sites of mutations described previously by Lane et al. (9). The numbers following the amino acids represent the codon number. The numbers in parentheses indicate the positions in the nucleotides sequence of DHPS to which primers correspond.

Sequencing of PCR products.

The purified PCR products were directly sequenced with an automated sequencer (ABI PRISM 377 DNA Sequencer; Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) by using the Prism Ready Reaction Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer). We sequenced both strands of the entire DHPS genes with primers AHUM and BHUM and the 5′ halves of DHPS genes with primers AHUM and BNEST in order to avoid sequence errors (see Fig. 1). When a mutation was found in the DHPS gene by direct sequencing, we confirmed the mutation by cloning of the PCR products. Briefly, the PCR products were ligated into the TA-cloning vector pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and were introduced into competent JM 109 cells (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Ten clones were selected for each specimen and were subjected to sequencing. The DNA and amino acids sequences were aligned with Genetyx-Mac, version 8.0, software (Software Development Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Relationship between co-trimoxazole treatment failure and DHPS mutations.

Co-trimoxazole treatment failure was defined as follows: failure to improve clinically in terms of fever (temperature, >38°C), dyspnea, or respiratory failure after the administration of co-trimoxazole for more than 10 days. The respiratory failure included the presence of either an arterial partial pressure of oxygen of less than 60 torr while the patient breathed ≥60% oxygen or an increased arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (5). The association between the treatment failure and DHPS mutations was analyzed by a two-tailed Fisher's exact test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Mutations in DHPS gene of P. carinii isolated from repeat BAL fluid specimens.

Four patients (patients 4, 17, 23, and 24) had repeat fiberoptic bronchoscopies during their hospitalizations. The periods between the first and the second BALs for patient 4, 17, 23, and 24 were 42, 20, 9, and 14 days, respectively. The patients received co-trimoxazole as therapy (patients 17, 23, and 24) or chronic suppression (patient 4) for PCP during these periods. The direct sequencing of the DHPS genes of P. carinii isolates from the second BAL fluid was performed as described above. DHPS mutations were determined by sequencing 10 independent clones derived from the PCR products.

RESULTS

Sequencing of DHPS genes.

The full length and 5′ halves of the DHPS genes in 24 specimens were sequenced with the AHUM-BHUM and AHUM-BNEST primer sets (Fig. 1). The 5′ halves of the DHPS genes were sequenced twice with different primer sets because this portion was previously reported to have several mutation sites (6, 8, 9, 12). As shown in Table 2, sequencing of both strands revealed that isolates from six patients (patients 5, 6, 10, 13, 17, and 18) (25%) had mutations at nucleotide position 165 and/or 171. The DHPS mutations of those isolates were confirmed by cloning the PCR products and sequencing 10 independent clones. All 10 clones derived from patient 10 had two nucleotide changes, at positions 165 (A→G) and 171 (C→T). Clones from patients 5, 6, 17, and 18 were mixtures of wild types and mutants with mutations at positions 165 (A→G) and 171 (C→T). Clones from patient 13 showed a mixture of the wild-type strain and mutants with mutations at positions 165 (A) and 171 (C→T). The nucleotide changes at positions 165 (A→G) and 171 (C→T) were nonsynonymous and resulted in amino acid changes from Thr to Ala at amino acid position 55 and from Pro to Ser at amino acid position 57, respectively (Table 2). The sequencing of the DHPS genes showed no mutations at amino acid positions 23, 60, 111, and 248 in this study (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

DHPS mutations in each patienta

| Patient no. | Sequence of DHPS mutantsb

|

No. of clones

|

Therapy for PCP | Treatment results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | Mutant | Wild type | |||

| 5 | ---165GCA CGG 171TCT--- | ---55Ala Arg 57Ser--- | 7 | 3 | Pentamidine | Success |

| 6 | ---165GCA CGG 171TCT--- | ---55Ala Arg 57Ser--- | 5 | 5 | Pentamidine | Success |

| 10 | ---165GCA CGG 171TCT--- | ---55Ala Arg 57Ser--- | 10 | 0 | Co-trimoxazole | Failure |

| 13 | ---165ACA CGG 171TCT--- | ---55Thr Arg 57Ser--- | 7 | 3 | Co-trimoxazole | Failure |

| 17 (first BAL fluid specimen) | ---165GCA CGG 171TCT--- | ---55Ala Arg 57Ser--- | 6 | 4 | Co-trimoxazole | Failure |

| 17 (second BAL fluid specimen) | ---165GCA CGG 171TCT--- | ---55Ala Arg 57Ser--- | 10 | 0 | ||

| 18 | ---165GCA CGG 171TCT--- | ---55Ala Arg 57Ser--- | 9 | 1 | Co-trimoxazole | Failure |

The mutations were confirmed by cloning and sequencing (10 clones) of each PCR product.

The nucleotide sequence of the wild type was 165ACA CGG 171CCT. The amino acid sequence of the wild type was 55Ala Arg 57Ser.

Relationship between co-trimoxazole treatment failure and DHPS mutations.

As shown in Table 3, treatment failures were observed more frequently in patients whose isolates had DHPS gene mutations than in those whose isolates had wild-type DHPS genes (n = 4 [100%] versus n = 2 [11.1%]; P = 0.002). Two patients (patients 5 and 6) whose isolates had DHPS mutations were successfully treated with intravenous pentamidine because they experienced drug-induced eruption due to co-trimoxazole during the first episodes of PCP. Thus, all patients whose isolates had DHPS mutations and who were treated with co-trimoxazole failed treatment, suggesting the strong correlation between the results of treatment with co-trimoxazole and DHPS mutations at amino acid position 55 or 57.

TABLE 3.

Co-trimoxazole treatment response of patients with PCP according to DHPS mutations in the patient's P. carinii isolates

| DHPS type | No. (%) of patients

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment failure | Treatment success | Total | |

| Mutant | 4 (100)a | 0 (0)b | 4 |

| Wild type | 2 (11.1)a | 16 (88.9) | 18 |

P = 0.002.

Due to skin eruptions, two patients (patients 5 and 6) whose isolates had DHPS mutations were switched from co-trimoxazole to intravenous pentamidine and were not included as treatment successes.

Mutations in DHPS genes of P. carinii isolated from repeat BAL fluid specimens.

Among the 24 patients enrolled in this study, 4 patients (patients 4, 17, 23, and 24) had repeat fiberoptic bronchoscopies. The second BAL fluid specimen obtained from patient 17 had a selection of mutants with Ala and Ser at amino acid positions 55 and 57, while the first BAL fluid sample from patient 17 had mixtures of Ala-Ser mutant and wild-type P. carinii isolates (Table 2). In contrast, the second BAL samples from three patients (patients 4, 23, and 24) who were successfully treated with co-trimoxazole did not contain isolates with the DHPS mutations (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In our study, co-trimoxazole treatment for PCP failed more frequently in patients whose isolates had DHPS mutations at amino acid codon 55 or 57 than in those whose isolates had the wild-type DHPS gene (n = 4 [100%] versus n = 2 [11.1%]; P = 0.002). According to an analysis of the crystal structure of the DHPS of Escherichia coli, which is homologous to the DHPS of P. carinii (1), Thr55 seems to form two hydrogen bonds with a pterin substrate, and Arg56 is involved in binding to both sulfonamide agents and the pterin substrate. Therefore, the substitution of Ala for Thr at codon 55 in DHPS may cause a structural change in Arg56 and result in inefficient binding to sulfonamide drugs. It was also described that substitution of Pro for Ser at codon 57 might affect the binding of Arg56 to the pterin substrate and sulfonamide agents (8). Consequently, DHPS mutations at codon 55 and/or 57 may lead to resistance to sulfonamide drugs and cause treatment failure when these agents are chosen for treatment. The second BAL fluid specimen from patient 17, obtained after 20 days of treatment with co-trimoxazole, had a selection of mutants with Ala and Ser at amino acid positions 55 and 57, while the first BAL fluid sample from the patient had mixtures of the mutant with the Ala-Ser mutation and wild-type isolates. This result strongly suggests that DHPS mutants with Ala and Ser at positions 55 and 57 have a phenotype of resistance to co-trimoxazole and are related to treatment failure. Thus, our data are consistent with the possibility that DHPS mutations are related to the failure of co-trimoxazole treatment for PCP. We believe that the mutations in the DHPS gene need to be determined by using the BAL fluid samples obtained at the time of diagnosis when patients with PCP clinically fail to respond to the administration of co-trimoxazole for more than 10 days.

In previous reports, it has been suggested that DHPS mutations at amino acid position 55 or 57 were related to failure of prophylaxis and treatment with sulfonamide (8, 11) and poor prognosis of AIDS-related PCP (6). In reports by Helweg-Larsen et al. (6) from Denmark and Kazanjian et al. (8) from the United States, the frequencies of DHPS mutations were 20.1% (n = 29) and 25.9% (n = 7), respectively. Since we found DHPS mutations in isolates from 6 (25.0%) of 24 patients, the frequency of mutations observed in this study in Japan was similar to those observed in studies in Denmark and in the United States.

None of the six patients whose isolates had DHPS mutations reported here were recently exposed to a sulfonamide drug (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) or a sulfone agent (dapsone) before they developed the current episodes of PCP; however, two of the patients (patients 5 and 6) had the prior episodes of PCP during which co-trimoxazole had been given for approximately 2 weeks. This suggests that P. carinii with DHPS mutations not only is selected by the pressure of sulfonamide or sulfone agents (6, 8, 9, 11) but also is incidentally acquired.

A patient with two recurrences of PCP who received co-trimoxazole prophylaxis was reported to respond to treatment with a large dose of co-trimoxazole (11). P. carinii isolates from both samples obtained from the patient during two episodes of PCP showed DHPS mutations (Ala55-Ser57). Meshnick (13) described that P. carinii strains with one or two DHPS mutations may be partly sulfa drug resistant. Although our data suggest that DHPS mutations may contribute to failures of co-trimoxazole treatment for PCP, a second genetic locus must certainly be involved in drug resistance in P. carinii.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan, the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan, the Japan Health Sciences Foundation, and the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the Organization for Pharmaceutical Safety and Research of Japan.

We thank M. Goto and A. Kawana-Tachikawa for helpful assistance with sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achari A, Somers D O, Champness J N, Bryant P K, Rosemond J, Stammers D K. Crystal structure of the anti-bacterial sulfonamide drug target dihydropteroate synthase. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:490–497. doi: 10.1038/nsb0697-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks D R, Wang P, Read M, Watkins W M, Sims P F, Hyde J E. Sequence variation of the hydroxy methyldihydropterin pyrophosphokinase: dihydropteroate synthase gene in lines of the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, with differing resistance to sulfa. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:397–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dallas W S, Gowen J E, Ray P H, Cox M J, Dev I K. Cloning, sequencing, and enhanced expression of the dihydropteroate synthase gene of Escherichia coli MC4100. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5961–5970. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5961-5970.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fermer C, Kristiansen B E, Skold O, Swedberg G. Sulfonamide resistance in Neisseria meningitidis as defined by site-directed mutagenesis could have its origins in other species. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4669–4675. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4669-4675.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gagnon S, Boota A M, Fischl M A, Baier H, Kirksey O W, La Voie L. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy for severe Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1444–1450. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011223232103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helweg-Larsen J, Benfield T L, Eugen-Olsen J, Lundgren J D, Lundgren B. Effects of mutations in Pneumocystis carinii dihydropteroate synthase gene on outcome of AIDS-associated P. carinii pneumonia. Lancet. 1999;354:1347–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03320-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes W T. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1381–1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712222972505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazanjian P, Locke A B, Hossler P A, Lane B R, Bartlett M S, Smith J W, Cannon M, Meshnick S R. Pneumocystis carinii mutations associated with sulfa and sulfone prophylaxis failure in AIDS patients. AIDS. 1998;12:873–878. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199808000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane B R, Ast J C, Hossler P A, Mindell D P, Bartlett M S, Smith J W, Meshnick S R. Dihydropteroate synthase polymorphisms in Pneumocystis carinii. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:482–485. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez P, Espinosa M, Greenberg B, Lacks S A. Sulfonamide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: DNA sequence of the gene encoding dihydropteroate synthase and characterization of the enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4320–4326. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.4320-4326.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mei Q, Gurunthan S, Masur H, Kovacs J A. Failure of co-trimoxazole in Pneumocystis carinii infection and mutations in dihydropteroate synthase gene. Lancet. 1998;351:1631–1632. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)77687-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merali S, Frevert U, Williams J H, Chin K, Bryan R, Clarkson A B. Continuous axenic cultivation of Pneumocystis carinii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2402–2407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meshnick S R. Drug-resistant Pneumocystis carinii. Lancet. 1999;351:1318–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.USPHS/IDSA Prevention of Opportunistic Infections Working Group. 1999 USPHS/IDSA guidelines for the prevention of opportunistic infections in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48(RR-10):1–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walzer P D, Foy J, Steele P, Kim C K, White M, Klein R S, Otter B A, Allegra C. Activities of antifolate, antiviral, and other drugs in an immunosuppressed rat model of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1935–1942. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.9.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weverling G J, Mocroft A, Ledergerber B, Kirk O, Gonzales-Lahoz J, d'Arminio Monforte A, Proenca R, Phillips A N, Lundgren J D, Reiss P. Discontinuation of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis after start of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 1999;353:1293–1298. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)03287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]