Abstract

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are common sports injuries that typically require surgical intervention. Autografts and allografts are used to replace damaged ligaments. The drawbacks of autografts and allografts, which include donor site morbidity and variability in quality, have spurred research in the development of bioengineered ligaments. Herein, the design and development of a cost-effective bench-top 3D braiding machine that fabricates scalable and tunable bioengineered ligaments is described. It was demonstrated that braiding angle and picks per inch can be controlled with the bench-top braiding machine. Pore sizes within the reported range needed for vascularization and bone regeneration are demonstrated. By considering a one-to-one linear relationship between cross-sectional area and peak load, the bench-top braiding machine can theoretically fabricate bioengineered ligaments with a peak load that is 9× greater than the human ACL. This bench-top braiding machine is generalizable to all types of yarns and may be used for regenerative engineering applications.

Keywords: Ligaments, Regenerative Engineering, Braiding, PLLA, tendon

Lay Summary

Worldwide 400,000 ACL reconstructions are performed annually. Rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction can take greater than 8 months, and the recurrence of ACL rupture is 30% in young active patients. Therefore, significant efforts have been made to develop an off-the-shelf ACL that is functionally superior to current ACL grafts. This study describes the development of a bench-top braiding machine that can be used in research laboratories to investigate the fabrication of bioengineered ACLs that are much stronger than current ACL grafts.

Future Work

Future studies will investigate the development of bioengineered ACL matrices made of nondegradable and degradable polymers, and in vivo experiments will be conducted to determine the functionality of the bioengineered ACL matrix.

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are a common sports related injury that necessitates surgical intervention. The current gold standard grafts for ACL reconstruction are hamstring or bone patellar tendon bone autografts and allografts [1,2]. However, these grafts have drawbacks which include donor site morbidity and variation in graft quality [1]. Therefore, research in the development of bioengineered ligaments has been explored to generate an off-the-shelf ligament that can serve as a mechanically competent scaffold to stabilize the knee and facilitate tissue regeneration. These bioengineered ligaments are made of natural or synthetic materials such as silk [3–5], poly (ε-caprolactone) [6,7], and poly (l-lactic) acid (PLLA) [8–14], and are usually fabricated by braiding yarns.

Three-dimensional braiding technology allows for the development of a structure with interconnected pores and an increased surface area, which permits greater cell attachment and tissue ingrowth [15]. Additionally, braiding allows for the development of mechanically robust structures that can recapitulate the biomechanical properties of the human ACL [15]. Knitting techniques for ACL matrices have also been explored, as they can provide greater internal connective spacing for tissue ingrowth [16]. However, the mechanical properties of knitted matrices suffer due to poor shear resistance and limited tensile strength [4,17,18]. Finally, 3D braiding technology may also offer the ability to generate pore size gradients that can vary along the length of the braided scaffold to support complex tissue regeneration [6].

Given the advantages of 3D braiding technology, Cooper et al. developed a PLLA 3D braided scaffold that was optimized for bone integration and ligamentization [9,10,19]. The 3D braided scaffold was composed of two bony attachment zones, which were braided with a higher braiding angle than the intra-articular zone of the scaffold. By controlling the braiding angle, the porosity of the braided scaffold could be tuned for optimal bone and soft tissue regeneration. The overall porosity of the braided scaffold was >50% and consisted of a bony region and an intra-articular region that had pore sizes of 150 μm and 200–250 μm, respectively [20]. Additionally, PLLA microfibers were utilized to mimic the diameter of collagen fascicles present in the native ACL. In a rabbit model, the efficacy of the braided scaffold was investigated at 4 and 12 weeks showing the ability of the scaffold to allow for bone tissue infiltration and ligamentization [19].

Such studies demonstrate the promise of braiding technology to generate bioengineered ligaments. Yet, the cost of braiding machines can be inhibitory for researchers in the field of regenerative engineering. To mitigate costs, finite element simulation models have been developed to predict the mechanical properties of braided scaffolds [21]. However, researchers still need to work with outside companies to produce braided scaffolds, which is costly and limits the ability to validate models.

The goal of this study was to develop a cost-effective track and column bench-top braiding machine and to evaluate the fabricated braided structures. Commercial braiding machines of the size described in this present study can range between $30,000 – $100,000. Herein, the design and development of a bench-top braiding machine, which can perform two-step and four-step braiding methods [22] is described and costs $10,000 to fabricate not including the cost of bobbin carriers. Braiding angle, picks per inch, pore size, and mechanical properties of the PLLA 3D braided scaffolds fabricated by the bench-top braiding machine are presented. Finally, the scalability of the braided scaffolds is demonstrated for various ACL reconstruction models.

Materials and methods

Design of braiding machine

The 3D braiding machine was designed to support the fabrication of rectangular and square braids and is featured in the work of Madhavarapu et al. [11]. Bobbin carriers were organized in tracks and columns, and the braiding machine was controlled via air cylinders (M series double acting cylinder, 2” bore, front nose mount, Numatics Inc.) that were connected to air valves (Figure 1A, red outline, L12BB452O000030, Numatics Inc.). Figure 1 A–D show the air valves in sequential order from all four sides of the braiding machine. A standard laboratory airline served as the source of compressed gas to operate the air cylinders. The outlet of the air valves (Figure 1B, red arrows) was split by a tee connector (Figure 1B, red circle) and fed into two air cylinders that were on the same side of the braiding machine and had one air cylinder in between them. 1/8” tubing for compressed air was used for the connections. The air cylinders had two ports for air outlet to control the forward and backward motion of the air cylinder. The direction of air into the air cylinder outlets was controlled by the air valve (Figure 1C, red outline) and was actuated by an electrical signal via a high voltage terminal block (Figure 1E, red arrow). A custom-made LABVIEW program was developed to control the circuits of the terminal block. Finally, the braiding machine was synchronized by connecting the air valves to various terminals of a control panel (Figure 1E) such that the four-step braiding process could be achieved as described by Byun et al. [23]. The braiding structure was fabricated by sequential track and column movements where the bobbin carriers were displaced one position at a time.

Figure 1. Electronics and valve system of the braiding machine.

A-D) Demonstrates the air valves in sequential order, from all four sides of the braiding machine, that control the motion of the pistons. A) Highlights an air valve. B) Highlights the outlet port of the air valve (red arrows), and the tee splitter that directs air to the air cylinders (red circle). C) Highlights a modified extension cord (red outline) which provides the electrical signal to control the air valve. E) Demonstrates the control panel of the braiding machine and the high voltage terminal (red arrow) that is connected to a computer via a D-sub cable.

Braiding Machine Pick Up Mechanism

Figure 2A is a rendered image of the braiding machine developed from engineering drawings in SolidWorks. Supplementary file 1 (Figure S1 – S12) shows detailed schematics that describe the entire engineering design of the braiding machine. The braiding point of the braiding processes was determined by modulating the height of the mandrel from the top of the bobbin carrier. The double arrow in Figure 2B demonstrates how the braiding height was characterized. The braiding point was defined by the position of the eyelet in Figure 2B. The yarns from the bobbin carrier were fed through the eyelet and attached to a mandrel. A DC voltage motor was utilized to turn the mandrel and thus pick up the yarns. A consistent braiding height was achieved by modulating the speed of the motor via a digital microprocessor controller and an incremental encoder (Dart, MD40P, Closed loop microprocessor-based DC motor speed control).

Figure 2. Overview of the braiding machine.

A) Rendered engineered drawing of the braiding machine. B) Image of the fabricated braiding machine. The braiding height (double arrow) is defined as the distance from the head of the bobbin carrier to the braiding point (BP, magnified image). The mandrel (above braiding point) is controlled by a digital DC drive, that is connected to an incremental encoder feedback system to control the digital input and mandrel speed.

Modularity of the Braiding Machine

The braiding machine frame was rectangular and could support up to 20 air cylinders with 6 cylinders along the length and 4 cylinders along the width. This arrangement of air cylinders was a 6 × 4 design (Figure 3A). By removing two air cylinders from the outer boundary of the lengths, a 4 × 4 square design was achieved (Figure 3B). Further modifications to the air cylinders were made to facilitate a 6 × 2, 4 × 2, and 2 × 2 design. Although not explored, the base plate could allow for a two-step braiding process and facilitate the addition of axial yarns as described by Du & Ko [22].

Figure 3. Comparison of rectangular and square braid design.

A) The rectangular design and B) square design of the braiding machine. C) Zoomed in image of A) demonstrating the size of the piston head for the 6 × 4 design. D) Zoomed in image of B) demonstrating the increased size of the piston head for the column position and removal of piston head for the square design.

The position of braiding carriers in the 6 × 4 design is demonstrated in Figure 3C. Spacers were placed in between the braiding carriers to maintain the track of the machine. A longer piston head was used in the 4 × 4 design and the piston head on the outer length boundaries was removed (Figure 3D). For the 6 × 4 design thirty-four bobbin carriers were used, with twenty-four bobbin carriers constituting the rectangular design, and an additional ten carriers outside of the rectangular design to facilitate the braiding action. Therefore, the number of bobbins for a rectangular braid design could be determined by the following equation,

| (1) |

where x and y are equal to the number of cylinders per width and length, respectively. Thus, seven and five bobbin carriers could be loaded along the length and width of the braiding frame, respectively, for a 6 × 4 braid design.

Fabrication of Braided Composites

Braids are composed of bundles of yarn, and the structural unit of yarn is a fiber. All fibers used throughout the study were extruded and supplied by Teleflex Medical OEM (Coventry, CT). Supplied PLLA fibers were composed of 30 filaments, which were approximately 15 – 20 μm in diameter. The denier of the PLLA fibers was between 60 – 80 deniers. PLLA fibers were plied together to produce a yarn. Twenty-four yarns were loaded onto the bobbin carriers, and a 4 × 4 square braid was fabricated and produced. Yarns were loaded onto triaxial bobbin carriers (Steeger, USA.), fed through the eyelet of the braiding point, and taped onto the mandrel. A LabVIEW program was developed to control the actuation of the pistons, with a time interval of 1500ms between signals. The braiding process continued until the braid reached the braiding point at which point the LabVIEW program was paused, and the braid was tied off using a twist tie. Next, the motor of the mandrel was adjusted to match the speed of braiding. The end of the braid was taped at the conclusion of the braiding process and subsequently cut with scissors, while holding the unbraided portion. The braided portion was removed, and the unbraided portion was attached to the mandrel. Finally, a hot knife was used to cut the braid to the desired length and to melt the fiber ends together simultaneously.

Analysis of Braiding Angle and Picks per Inch

The fabricated braids were imaged using reflective light, and the braiding angle was measured in ImageJ (Figure 4A). The braiding angle was defined by measuring the acute angle between interlocking yarns. Three braiding heights were used for the analysis of braiding angle, 33 cm, 53 cm, and 68 cm. For the analysis of picks/inch, braiding heights of 37 cm and 68 cm were used. A pick was defined as the distance between adjacent interlocking yarns along the length of the braid (Figure 4B & C).

Figure 4. Characterization of braiding angle and picks per inch of braided constructs.

A) Reflective light image of a braided construct demonstrating the measurement of a braiding angle (yellow acute angle). B) Macro-view of a square braid that was braided at the height of 37 cm and C) 68 cm. The yellow line demonstrates the length of a pick, which is defined as the intersection between two adjacent interlocking yarns. D) Braiding height significantly reduces the picks/inch of a braided construct (n = 2 for 37cm, n = 3 for 68cm).

Mechanical Testing of Square Braids and Yarns

Square braids composed of 12 multifilament PLLA fibers of 60 deniers were plied together to form PLLA yarns (720 deniers) and were fabricated at a height of 37 and 67 cm to determine the relationship between braiding height and mechanical properties. PLLA fibers of 70 deniers were plied to fabricate 16 (1120 denier), 49 (3430 deniers), and 65 (4550 deniers) ply yarns to investigate the relationship between denier (the textile term for the cross-sectional area) and mechanical properties. PLLA square braids with a cross-sectional area of 6.25 mm2 and 12.57 mm2 were fabricated by loading 14 and 65 ply yarns onto the bobbin carriers, respectively. An Instron P5200 machine with a 2kN load cell and pneumatic action grips for cord and yarns (Instron 2714–040) was used for tensile tests (n = 3). The length of braided constructs was 37 cm. Braided constructs were held in the grips by applying 40 psi on the pneumatic action grips. A 2% strain rate was applied for tensile tests, and three samples were tested per group.

Pore Size Analysis

Four x four braids were fabricated at a height of 67 cm and were composed of 720 denier PLLA yarns. Braids were cut to a length of 3 cm (n = 3). Mercury intrusion porosimetry was conducted by an independent laboratory (Porous Materials, Inc.) to evaluate pore sizes of the braided structures, as described previously by Cooper et al. [8,9,19].

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 8 was used for statistical analysis. A student t-test was used for comparison between two groups and a one-way ANOVA test with a Tukey post-hoc test was used for comparison between three groups. The difference between experimental groups was considered statistically significant at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Characterization of Braiding Features

The features of a braid can be characterized by the braiding angle and the picks per inch. To gain an understanding of the relationship of braiding height to these parameters, braids were fabricated at different heights. Braiding height was found to have an inverse relationship with braiding angle as braids fabricated at a braiding height of 33, 53, and 68 cm were found to have braiding angles of 29°, 24°, and 18° respectively. Figure 4B & C demonstrate a gross view of braids fabricated at 37 cm and 67 cm of height, respectively. The yellow line demonstrates the length of a pick in each braid. The picks/inch for the 37 cm and 67 cm braid were 15.00 ± 1.41 picks/inch and 10.67 ± 1.155 picks/inch, respectively, and was statistically significant (Figure 4D, p-value = 0.03). To gain an approximation of the pore sizes, mercury intrusion porosimetry was conducted. Differences between scaffolds were not found. However, evaluation of the 67cm scaffold suggested that 30% of the measured pore sizes were greater than 100 μm and had a median pore size of 39.2 ± 4.5 μm.

Mechanical Properties of Braided Scaffolds and Yarns

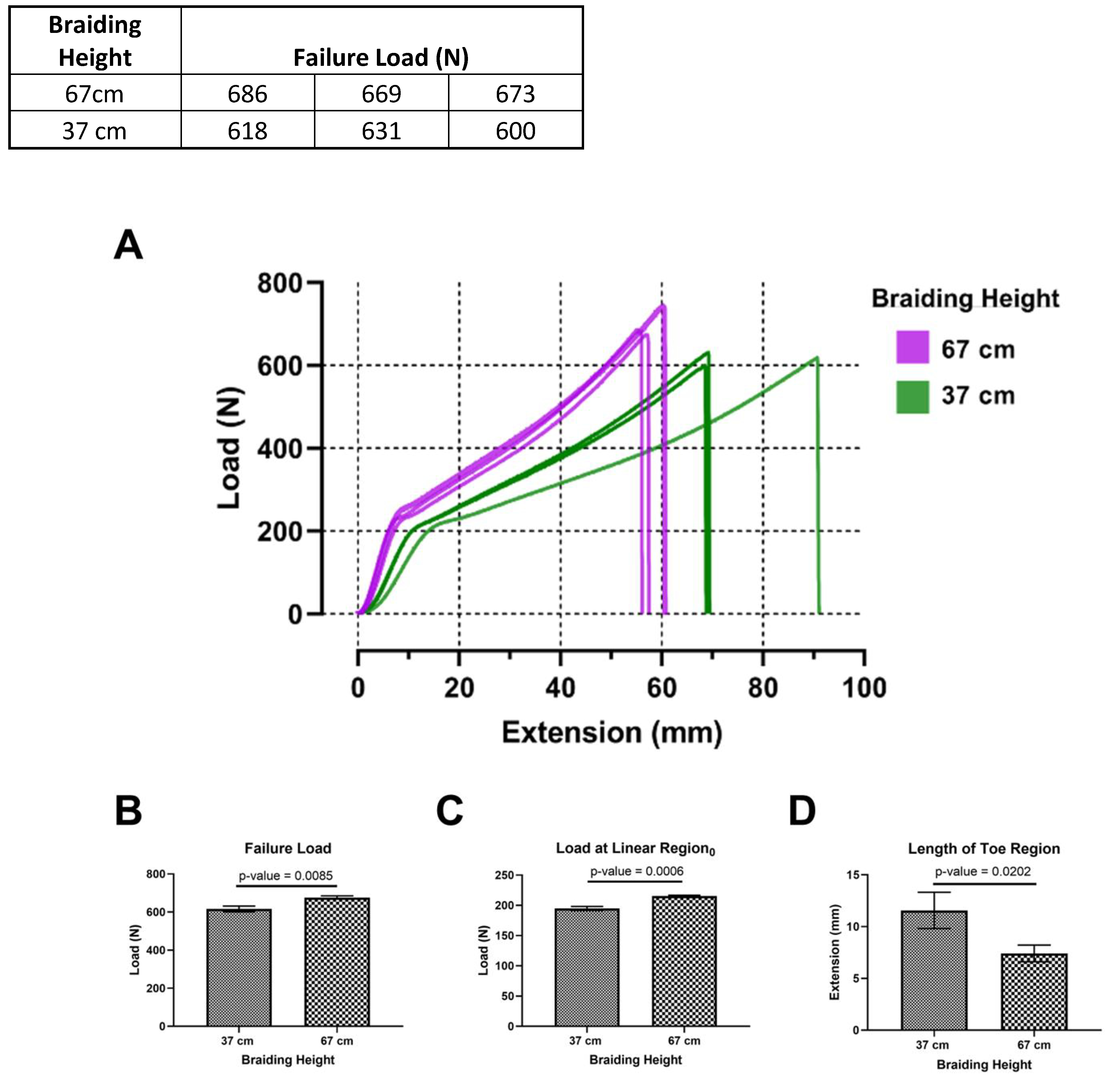

Tensile tests were conducted to determine the mechanical properties of braided scaffolds as a function of braiding height. The braided scaffold always ruptured in the mid-substance as opposed to jaw break failures. Figure 5A shows the load-versus-extension curve of braided scaffolds fabricated at 37 and 67 cm. The mechanical behavior of the braided scaffolds is similar to ligaments as a nonlinear toe region followed by a linear region was found. In the nonlinear toe region, yarns of the braided scaffold are recruited into the loading axis [24]. The linear region represents loading with most of the yarns aligned with the loading axis. The failure load was 616.4 ± 15.37 N and 676.2 ± 8.8 N for braids fabricated at heights of 37 and 67 cm (Figure 5B, p-value = 0.0085). The load at the beginning of the linear region was 194.9 ± 3.39 N and 215.6 ± 1.19 N at the height of 37 and 67 cm (Figure 5C, p-value = 0.0046). Finally, the length of the toe region was 11.57 ± 1.75 mm and 7.41 ± 0.81 mm at a height of 37 and 67 cm (Figure 5D, p-value = 0.0375). This demonstrates that the designed braiding machine can tune mechanical properties of braided scaffolds by adjusting the braiding height.

Figure 5. Mechanical properties of a square braid as a function of braiding height.

A) Load versus extension curve of square braids. B) The failure load and C) yield load is significantly higher at a braiding height of 67cm. D) Extension at yield is significantly higher at a braiding height of 37 cm.

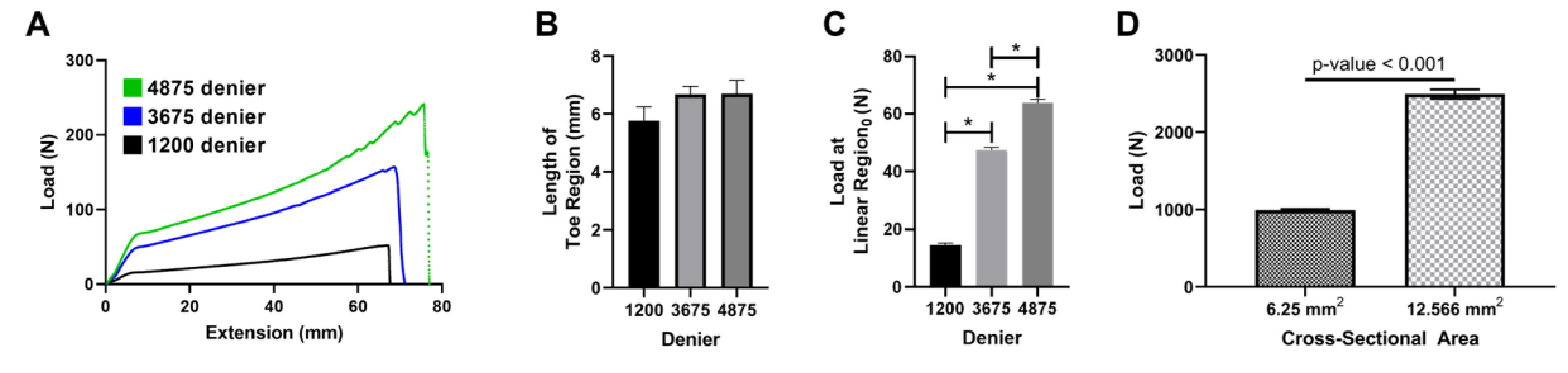

Mechanical properties of yarns were also investigated to determine the relationship between denier (or more simply cross-sectional area) and failure load. Figure 6A demonstrates a representative load-versus-extension plot of the yarns with deniers of 1200, 3675, and 4875. It was found that the length of the toe region was not affected by denier, but the load at the beginning of the linear region was (Figure 6B & C). Finally, the mechanical properties of braided scaffolds with different cross-sectional areas were investigated. Failure loads of 983 ± 15.37 N and 2494 ± 59.63 N were found for cross-sectional areas of 6.25 and 12.57 mm2, respectively (Figure 6D, p-value = 0.003). The increase in cross-sectional area was 2-fold, and the increase in failure load was 2.5-fold.

Figure 6. Effect of yarn and braid cross-sectional area on failure load.

A) Representative load vs extension graphs for 1200 deniers (black line), 3675 deniers (blue line), and 4875 deniers (green line). B) Length of toe region and C) load at yield linear region0 for increasing denier of yarns (* p-value < 0.001). D) Failure load of braided construct of differing sizes.

Discussion

The design and characterization of a cost-effective bench-top 3D braiding machine that can be adapted for regenerative engineering applications and fabricate scaffolds with tunable shape, braiding angle, picks per inch, and mechanical properties was described. By modulating the number of bobbin carriers and the size of the piston head, the bench-top braiding machine can fabricate rectangular and square braids. Similarly, by varying the braiding height, the bench-top braiding machine facilitated the fabrication of braided scaffolds with varying braiding angles. Previously, Cooper et al. demonstrated the ability to fabricate circular and rectangular braids with braiding angles between 25° to 33° using an industrial-sized braiding machine. Similarly, the bench-top braiding machine in the present study demonstrated braiding angles between 15° to 30° [9]. Additionally, mercury porosimetry data demonstrated pore sizes in the range of 1 – 260 μm. These pore diameters are a function of the space between braided yarns as well as the space between fibers in the yarns. Therefore, the calculated median pore sizes from porosimetry data may skew the results to a smaller diameter due to smaller pore sizes in between the fibers of the yarns. The goal of 3D braiding for bioengineered ligaments is to develop an interconnected pore network with pore sizes that are suitable for both bone and ligament regeneration. Studies have indicated that a minimum pore size of 100 microns is needed for vascularization, which facilitates nutrient and oxygen transport needed for bone regeneration [25], and that a pore size greater than 250 μm is optimal for cellular infiltration and subsequent bone tissue repair [25]. Therefore, the pore sizes of the braided structures indicate suitability for vascularization and bone regeneration in vivo.

The braided scaffold fabricated by the bench-top braiding machine showed that braiding characteristics could modulate mechanical properties. Increased failure and yield loads at higher braiding heights (lower braiding angles) can be attributed to the alignment of the yarns in the direction of the loading axis. As the braiding height is lowered (higher braiding angle), the yarns are less aligned with the loading axis. Freeman et al. describe the relationship between tensile force and compressive forces placed on yarns as a function of braiding angle [24]. In Freeman et al.’s work, it was demonstrated that the braiding angle has a direct relationship with the compressive forces placed on the yarns when the braided scaffold is loaded in tension. Furthermore, a direct relationship between the length of the toe region and the braiding angle was demonstrated. This suggests that greater strain is needed to recruit the yarns in the braided scaffold with the line of force [24]. The present study corroborated the relationship between braiding height (i.e. braiding angle) versus the length of the toe region (Figure 5D). Furthermore, the results suggest that yarn denier does not affect the length of the toe region. Finally, the data also suggests that the peak load of the scaffold decreases as the braiding angle is increased (Figure 5B). This is likely due to the compressive/shear force placed on the yarns causing premature rupture of the braided scaffold as described previously [24].

The bench-top 3D braiding machine also demonstrated the ability to fabricate bioengineered ligaments that far exceed the strength of human ACLs. The cross-sectional area of the native ACL ranges from 44.4 mm2 to 57.5 mm2 with younger patients (16 – 26 years old) having a smaller cross-sectional area in comparison to older patients (48–86 years old) [26]. The peak load of a human ACL ranges from 734 N to 1730 N and depends on the subjec’s age with younger patients (16 – 26 years old) exhibiting higher peak loads than older patients (48–86 years old) [26]. Furthermore, during daily activities, the loads for the ACL have been calculated to be 169 N during normal walking, below 100 N when ascending stairs and ascending/descending a ramp, and 445 N when descending stairs [27]. By assuming a one-to-one linear relationship between cross-sectional area and peak load, the PLLA 3D braided structures could achieve a peak load of 8,816 N to 11,412 N for the cross-sectional areas of 44.4 mm2 to 57.5 mm2. In human ACL reconstruction, the bone tunnels for hamstring grafts are drilled with a 7.5 – 9 mm drill bit and bone-patellar tendon-bone tunnels are drilled with a 10mm drill bit [28]. A 10 mm diameter bone tunnel gives a cross-sectional area of 78.5 mm2, and based on a hypothetical linear scale up from the current 12.566 mm2 graft in this study, it may be possible to achieve a peak load of 15,580 N. Thus, this study suggests the potential to engineer a ligament with peak loads 9× greater than the human ACL and 35× the physiological loads seen during daily activities.

Finally, the bench-top braiding machine can fabricate both rectangular and square braids through the modulation of bobbin carrier position. The adaptation of the thickness of the braid morphology provides flexibility to various graft fixation techniques used in ACL reconstruction. Milano et al. demonstrated that suspension fixation devices (Bio-Transfix, Transfix, and Swing Bridge) demonstrated the highest peak loads at failure for a folded over hamstring graft, otherwise known as a two-limb graft [29]. Suspension fixation of hamstring grafts require the graft to be folded over a screw or a rope. Utilizing the braiding machine described in this present study, Mengsteab et al. recently investigated the use of a two-limb bioengineered ACL matrix with suture fixation in a rabbit ACL reconstruction model [13]. Furthermore, square braids fabricated with this braiding machine were also investigated in a sheep ACL reconstruction model [30]. In order to facilitate these fixation techniques, bioengineered ligaments need to be designed to maximize their conformity into a bone tunnel and to achieve this, the aspect ratio of the folded graft needs to be minimized. Therein lies the limitation of square and rectangular braids for ACL reconstruction as the bone tunnels in which they are implanted are circular. However, the bench-top braiding machine facilitates a 6 × 4 braiding design, which allows for maintenance of the braid’s thickness while increasing its width. Therefore, when folding the braid in half a lower aspect ratio is achieved in comparison to the 4 × 4 braided design. The adaptability of the bench-top braiding machine to both designs allows for the optimization of bioengineered ligament with surgical fixation methods in mind.

Conclusions

A cost-effective bench-top 3D braiding machine that can be utilized for regenerative engineering applications was developed. The bench-top 3D braiding machine can be adapted to develop rectangular and square braid designs, which are of importance in the clinical implementation of bioengineered ligaments. The braiding angle of braided scaffolds could be tuned by adjusting the height of the mandrel on the bench-top braiding machine. Finally, the data suggests that PLLA yarns can be used to generate braided scaffolds with failure loads that are 9× greater than the human ACL using the bench-top 3D braiding machine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Center for Biomedical, Biological, Physical and Engineering Sciences, NIH R01AR063698, and NIH DP1AR068147. Paulos Y. Mengsteab was funded by NIH R01AR063698-02S1. Mohammed A. Barajaa was funded by Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Competing Interests

Dr. Cato T. Laurencin has the following competing financial interests: Biorez, Globus, HOT, HOT Bone, Kuros Bioscience, NPD & Cobb (W Montague) NMA Health Institute. Dr. Lakshmi S. Nair has the following competing financial interests: Biorez. The authors have no non-financial competing interest.

References

- 1.Mengsteab PY, Nair LS, Laurencin CT. The past, present and future of ligament regenerative engineering. Regen Med [Internet]. Future Science Group; 2016. [cited 2019 Jan 9];11:871–81. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27879170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mengsteab PY, McKenna M, Cheng J, Sun Z, Laurencin CT. Regenerative Engineering of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament. In: Oliveira JM, Reis RL, editors. Regen Strateg Treat Knee Jt Disabil [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 391–410. Available from: 10.1007/978-3-319-44785-8_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teuschl A, Heimel P, Nürnberger S, Van Griensven M, Redl H, Nau T. A novel silk fiber-based scaffold for regeneration of the anterior cruciate ligament: Histological results from a study in sheep. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine; 2016. [cited 2016 May 16];44:1547–57. Available from: http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/early/2016/03/07/0363546516631954.full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan H, Liu H, Toh SL, Goh JCH. Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and silk scaffold in large animal model. Biomaterials [Internet]. 2009. [cited 2015 Mar 17];30:4967–77. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142961209005791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altman GH, Horan RL, Lu HH, Moreau J, Martin I, Richmond JC, et al. Silk matrix for tissue engineered anterior cruciate ligaments. Biomaterials [Internet]. 2002. [cited 2016 May 17];23:4131–41. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142961202001564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laurent CP, Ganghoffer JF, Babin J, Six JL, Wang X, Rahouadj R. Morphological characterization of a novel scaffold for anterior cruciate ligament tissue engineering. J Biomech Eng [Internet]. 2011;133:065001. Available from: 10.1115/1.4004250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurlek AC, Sevinc B, Bayrak E, Erisken C. Synthesis and characterization of polycaprolactone for anterior cruciate ligament regeneration. Mater Sci Eng C [Internet]. Elsevier; 2017. [cited 2019 Jun 5];71:820–6. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0928493116308748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu HH, Cooper JA, Manuel S, Freeman JW, Attawia MA, Ko FK, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using braided biodegradable scaffolds: In vitro optimization studies. Biomaterials [Internet]. 2005. [cited 2014 Sep 6];26:4805–16. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142961204010543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper JA, Lu HH, Ko FK, Freeman JW, Laurencin CT. Fiber-based tissue-engineered scaffold for ligament replacement: Design considerations and in vitro evaluation. Biomaterials [Internet]. 2005. [cited 2014 Sep 6];26:1523–32. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142961204004909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper JA, Bailey LAO, Carter JN, Castiglioni CE, Kofron MD, Ko FK, et al. Evaluation of the anterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament, achilles tendon and patellar tendon as cell sources for tissue-engineered ligament. Biomaterials [Internet]. 2006. [cited 2014 Sep 16];27:2747–54. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142961205011671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madhavarapu S, Rao R, Libring S, Fleisher E, Yankannah Y, Freeman JW. Design and characterization of three-dimensional twist-braid scaffolds for anterior cruciate ligament regeneration. Technology [Internet]. World Scientific Publishing Company; 2017. [cited 2019 Jun 19];05:98–106. Available from: http://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/S2339547817500066 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahner J, Hinüber C, Breier A, Siebert T, Brünig H, Heinrich G. Adjusting the mechanical behavior of embroidered scaffolds to lapin anterior cruciate ligaments by varying the thread materials. Text Res J. 2015;85:1431–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mengsteab PY, Conroy P, Badon M, Otsuka T, Kan HM, Vella AT, et al. Evaluation of a bioengineered ACL matrix’s osteointegration with BMP-2 supplementation. PLoS One. 2020;15:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu X, Mengsteab PY, Narayanan G, Nair LS, Laurencin CT. Enhancing the Surface Properties of a Bioengineered Anterior Cruciate Ligament Matrix for Use with Point-of-Care Stem Cell Therapy. Engineering. Elsevier Ltd; 2020; [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurencin CT, Nair LS. Next Generation Devices and Technologies Through Regenerative Engineering. Healthc Eng. Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 21–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Qi YY, Wang LL, Yin Z, Yin GL, Zou XH, et al. Ligament regeneration using a knitted silk scaffold combined with collagen matrix. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3683–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alagirusamy R, Padaki N. Introduction to Braiding. In: Rana S, Fangueiro R, editors. Braided Struct Compos. Boca Raton, Fl: CRC Press; 2015. p. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akbari M, Tamayol A, Bagherifard S, Serex L, Mostafalu P, Faramarzi N, et al. Textile Technologies and Tissue Engineering: A Path Toward Organ Weaving. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5:751–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper JA, Sahota JS, Gorum WJ, Carter J, Doty SB, Laurencin CT. Biomimetic tissue-engineered anterior cruciate ligament replacement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet]. 2007. [cited 2014 Sep 16];104:3049–54. Available from: http://www.pnas.org/content/104/9/3049.full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samuel PS, Mintz BR, Lee KL, Cooper JA. Ligament regenerative engineering. In: Laurencin CT, Khan Y, editors. Regen Eng. Boca Raton, Fl: Taylor & Francis Group; 2013. p. 331–59. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gereke T, Döbrich O, Aibibu D, Nowotny J, Cherif C. Approaches for process and structural finite element simulations of braided ligament replacements. J Ind Text. 2017;47:408–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du GW, Ko FK. Unit cell geometry of 3-D braided structures. J Reinf Plast Compos [Internet]. Sage PublicationsSage CA: Thousand Oaks, CA; 1993. [cited 2020 Feb 26];12:752–68. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/073168449301200702 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byun JH, Chou TW. Process-microstructure relationships of 2-step and 4-step braided composites. Compos Sci Technol [Internet]. Elsevier; 1996. [cited 2019 Aug 24];56:235–51. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0266353895001123 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman JW, Woods MD, Cromer DA, Wright LD, Laurencin CT. Tissue engineering of the anterior cruciate ligament: The viscoelastic behavior and cell viability of a novel braid-twist scaffold. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed [Internet]. Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. [cited 2016 Aug 13];20:1709–28. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1163/156856208X386282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bose S, Roy M, Bandyopadhyay A. Recent advances in bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Trends Biotechnol [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2012. [cited 2019 May 8];30:546–54. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22939815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noyes F, Grood E. The strength of the anterior cruciate ligament in humans and Rhesus monkeys [Internet]. J. Bone Jt. Surg The American Orthopedic Association; 1976. Dec. Available from: http://jbjs.org/content/58/8/1074.abstract [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dargel J, Gotter M, Mader K, Pennig D, Koebke J, Schmidt-Wiethoff R. Biomechanics of the anterior cruciate ligament and implications for surgical reconstruction. Strateg Trauma Limb Reconstr [Internet]. 2007. [cited 2015 Apr 16];2:1–12. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2321720&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulsen MR, Johnson DL. Graft selection in anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Orthopedics [Internet]. 2010. [cited 2018 Jun 30];33:197–207. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8998900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milano G, Mulas PD, Ziranu F, Piras S, Manunta A, Fabbriciani C. Comparison Between Different Femoral Fixation Devices for ACL Reconstruction With Doubled Hamstring Tendon Graft: A Biomechanical Analysis. Arthrosc - J Arthrosc Relat Surg [Internet]. W.B. Saunders; 2006. [cited 2019 May 8];22:660–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749806306005652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh WR, Bertollo N, Arciero RA, Stanton RA, Poggie RA. Long-term in-vivo evaluation of a resorbable PLLA scaffold for regeneration of the ACL. Orthop J Sport Med [Internet]. SAGE Publications; 2015. [cited 2015 Nov 16];3. Available from: http://ojs.sagepub.com/content/3/2_suppl/2325967115S00033.abstract [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.