Abstract

Numerous studies have focused on whether the marital status has an impact on the prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, but none have focused on lung adenocarcinoma.

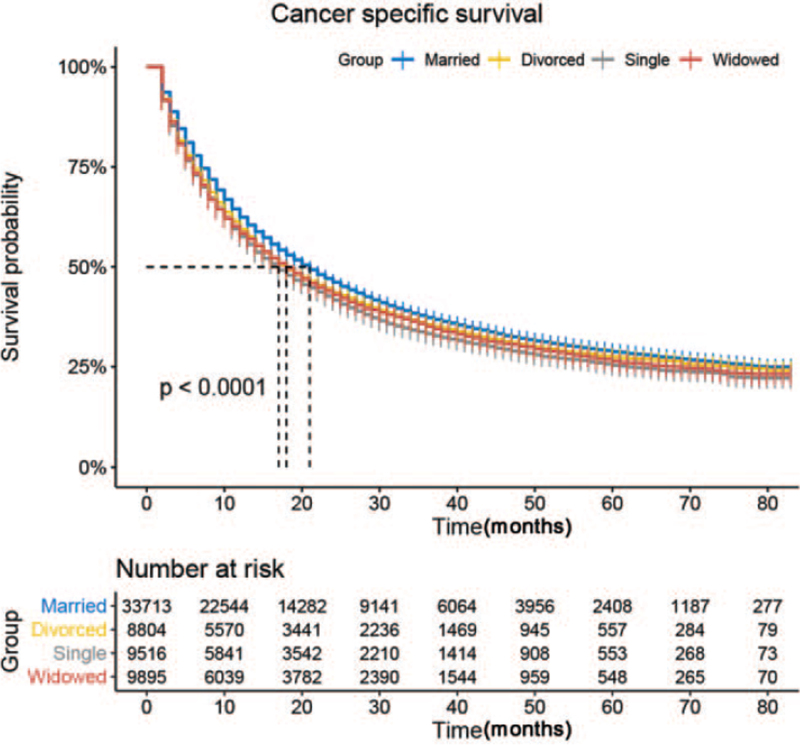

We selected 61,928 eligible cases with lung adenocarcinoma from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database from 2004 to 2016 and analyzed the impact of marital status on cancer-specific survival (CSS) using Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression analyses.

We confirmed that sex, age, race, cancer TNM stage and grade, therapeutic schedule, household income, and marital status were independent prognostic factors for lung adenocarcinoma CSS. Multivariate Cox regression showed that widowed patients had worse CSS (hazard ratio 1.26, 95% confidence interval 1.20–1.31, P < .001) compared with married patients. Subgroup analysis showed consistent results regardless of sex, age, cancer grade, and TNM stage. However, the trend was not significant for patients with grade IV cancer.

These results suggest that marital status is first identified as an independent prognostic factor for CSS in patients with lung adenocarcinoma, with a clear association between widowhood and a high risk of cancer-specific mortality. Psychological and social support are thus important for patients with lung adenocarcinoma, especially unmarried patients.

Keywords: cancer-specific survival, lung adenocarcinoma, marital status, SEER program, survival analysis

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is considered the most common cancer worldwide, affecting 1.8 million people and accounting for 13% of all diagnosed cancers. It is also the main cause of cancer-related death worldwide, being responsible for 19% of all cancer-related deaths representing about 1.6 million people.[1] Despite new treatments, the 5-year survival rate remains as low as 12% to 15%.[2] In the last 2 decades, adenocarcinoma has replaced squamous cell cancer as the most prevalent subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),[2] accounting for 40% of all lung cancer patients.[3]

Although previous studies have examined the impacts of demographic factors (e.g., age and sex) and clinicopathologic factors (e.g., presence of pulmonary symptoms, larger tumor size, nonsquamous histology, vascular invasion) on cancer survival,[4] the impact of marriage is still unclear. Wu et al[4] demonstrated that marriage was protective on the survival of patients with NSCLC; however, Kumi et al[5,6] and Jatoi et al[7] reached opposing conclusions. In addition, as far as we have known, previous researchers did not pay attention to the impact of marital status on the survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma.

In the present study, we aimed to explore the relationship between marital status and the prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma by analyzing data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry database.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data source

All data in our study were acquired from the SEER 18 registry, which is currently the largest publicly available cancer database, covering approximately 28% of the US population.[8] We used the Incidence-SEER 18 Registries Custom Data with additional treatment fields, Nov 2018 Sub (1975– 2016 varying), which contains information on patient demographics and cancer characteristics, including sex, age at diagnosis, race, marital status, cancer TNM stage, and grade at diagnosis, treatment regimen, and patient survival time. We took 2004 as the first year of the study, given that several employed covariates were introduced in SEER in that year.[9] Ethical approval was waived by the institutional review board of the First People's Hospital of Yongkang City because SEER data is publicly accessible and deidentified.

2.2. Patient selection

Patients with International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) site code C34.0-C34.9 from 2004 to 2016 were identified in the SEER database. Unless they were excluded by the following criteria: ICD-O-3 morphology code did not indicate lung adenocarcinoma (8140); diagnosis of cancer made at autopsy; age at diagnosis <18 years; prior malignancy diagnosed; cause of death unknown; survival time unknown or <1 month; and incomplete clinical information.

2.3. Study variables

Information on the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics was extracted from the database, including sex, age at diagnosis, race, tumor grade, AJCC TNM stage, marital status, surgical information, radiotherapy information, and chemotherapy information. Group assignments were made via the following factors: age (<65 and ≥65 years old); race (White, Black, and other); marital status (married, single, separated, divorced, and widowed); separated and divorced patients were combined into a single category in alignment with previous studies.[10–12]); tumor grade (I, well-differentiated; II, moderately differentiated; III, poorly differentiated; IV undifferentiated); surgery (yes or no); and radiotherapy and chemotherapy (yes or no/unknown). Median household income was calculated to represent socioeconomic status. The primary study endpoint was cancer-specific survival (CSS). For CSS analysis, deaths from lung adenocarcinoma were considered events, while survivors or deaths attributed to other causes were censored.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and compared using χ2 tests across groups according to marital status. CSS was estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Factors with a P value <.05 in log-rank tests were entered into the multivariate Cox regression model. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 24; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Statistical significance was set at a 2-sided P < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline patient characteristics

We selected 61,928 eligible cases with lung adenocarcinoma (29,460 males and 32,468 females) through the SEER database from 2004 to 2016. Of these, 33,713 patients (54.4%) were married, 8804 were divorced (14.2%), 9516 were single (15.4%), and 9895 were widowed (16.0%). Most married patients were men (55.6%), and most widowed patients were women (77.6%). Most widowed patients were ≥65 years old (87.4%), while most single patients were <65 years old (61.5%). Single patients were more likely to have TNM stage IV cancer (57.1%). Married patients had the highest proportions of patients with surgery (28.1%) and chemotherapy (60.5%). While widowed patients had the lowest proportions of patients with radiotherapy (60.3%) and chemotherapy (57.6%). The patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinoma.

| Characteristic | Married | Divorced | Single | Widowed | Total | P value |

| Number of patients | 33,713 (54.4) | 8804 (14.2) | 9516 (15.4) | 9895 (16) | 61,928 (100) | |

| Sex | <.001 | |||||

| Male | 18,731 (55.6) | 3742 (42.5) | 4767 (50.1) | 2220 (22.4) | 29,460 (47.6) | |

| Female | 14,982 (44.4) | 5062 (57.5) | 4749 (49.9) | 7675 (77.6) | 32,468 (52.4) | |

| Age | <.001 | |||||

| <65 | 13,783 (40.9) | 4326 (49.1) | 5850 (61.5) | 1251 (12.6) | 25,210 (40.7) | |

| ≥65 | 19,930 (59.1) | 4478 (50.9) | 3666 (38.5) | 8644 (87.4) | 36,718 (59.3) | |

| Race | <.001 | |||||

| White | 26,685 (79.2) | 6942 (78.9) | 6217 (65.3) | 7911 (79.9) | 47,755 (77.1) | |

| Black | 2759 (8.2) | 1384 (15.7) | 2637 (27.7) | 1042 (10.5) | 7822 (12.6) | |

| Other | 4269 (12.7) | 478 (5.4) | 662 (7) | 942 (9.5) | 6351 (10.3) | |

| Grade | <.001 | |||||

| I | 2549 (7.6) | 597 (6.8) | 542 (5.7) | 826 (8.3) | 4514 (7.3) | |

| II | 7176 (21.3) | 1742 (19.8) | 1739 (18.3) | 2111 (21.3) | 12,768 (20.6) | |

| III | 8714 (25.8) | 2301 (26.1) | 2614 (27.5) | 2218 (22.4) | 15,847 (25.6) | |

| IV | 176 (0.5) | 49 (0.6) | 58 (0.6) | 45 (0.5) | 328 (0.5) | |

| Unknown | 15,098 (44.8) | 4115 (46.7) | 4563 (48) | 4695 (47.4) | 28,471 (46) | |

| TNM stage | <.001 | |||||

| I | 7111 (21.1) | 1904 (21.6) | 1784 (18.7) | 2490 (25.2) | 7111 (21.5) | |

| II | 2315 (6.9) | 639 (7.3) | 623 (6.5) | 796 (8) | 2315 (7.1) | |

| III | 5930 (17.6) | 1649 (18.7) | 1675 (17.6) | 1716 (17.3) | 5930 (17.7) | |

| IV | 18,357 (54.5) | 4612 (52.4) | 5434 (57.1) | 4893 (49.4) | 18,357 (53.8) | |

| Surgery | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 9467 (28.1) | 2322 (26.4) | 2125 (22.3) | 2286 (23.1) | 16,200 (26.2) | |

| No | 24,246 (71.9) | 6482 (73.6) | 7391 (77.7) | 7609 (76.9) | 45,728 (73.8) | |

| Radiotherapy | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 14,900 (44.2) | 4077 (46.3) | 4252 (44.7) | 3933 (39.7) | 27,162 (43.9) | |

| None, refused or unknown | 18,813 (55.8) | 4727 (53.7) | 5264 (55.3) | 5962 (60.3) | 34,766 (56.1) | |

| Chemotherapy | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 20,380 (60.5) | 4850 (55.1) | 5270 (55.4) | 4193 (42.4) | 34,693 (56) | |

| No/unknown | 13,333 (39.5) | 3954 (44.9) | 4246 (44.6) | 5702 (57.6) | 27,235 (44) | |

| Cancer-specific death | <.001 | |||||

| Events | 20,452 (60.7) | 5469 (62.1) | 6031 (63.4) | 6112 (61.8) | 38,064 (61.5) | |

| Censored | 13,261 (39.3) | 3335 (37.9) | 3485 (36.6) | 3783 (38.2) | 13,261 (38.5) | |

| Median household income | <.001 | |||||

| <3946 | 8319 (24.7) | 2374 (27) | 2235 (23.5) | 2418 (24.4) | 15,346 (24.8) | |

| 3946–4494 | 8118 (24.1) | 2178 (24.7) | 2727 (28.7) | 2469 (25) | 15,492 (25) | |

| 4494–5400 | 8384 (24.9) | 2277 (25.9) | 2355 (24.7) | 2544 (25.7) | 15,560 (25.1) | |

| ≥5400 | 8892 (26.4) | 1975 (22.4) | 2199 (23.1) | 2464 (24.9) | 15,530 (25.1) |

3.2. Effect of marital status on lung adenocarcinoma CSS

We estimated the lung adenocarcinoma CSS by the Kaplan–Meier method and analyzed it using log-rank tests. CSS was strongly associated with marital status (P < .001, Fig. 1), and married patients had the highest CSS (28.3%) (Table 2). Multivariate analysis revealed that divorced (hazard ratio (HR) =1.1, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.05–1.15, P < .001), single (HR = 1.1, 95% CI: 1.05–1.15, P < .001), and widowed (HR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.15–1.26, P < .001) patients had higher risks of cancer-specific death compared with married patients after adjusting the covariates. In addition, sex, race, cancer TNM stage and grade, therapeutic schedule, and median household income were also identified as independent factors related to CSS. Briefly, male sex, higher tumor grade, higher TNM stage, low median household income, no surgery, and no chemotherapy were associated with higher risks of lung adenocarcinoma-specific death.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of lung adenocarcinoma cancer-specific survival by marital status.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of lung adenocarcinoma cancer-specific survival.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| Variable | 5-yr CSS | Log rank χ2 test | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value |

| Sex | 634.3 | <.001 | |||

| Male | 23.8% | Reference | |||

| Female | 31.1% | 0.77 (0.75–0.8) | <.001 | ||

| Age | 4.8 | .030 | |||

| <65 | 27.5% | Reference | |||

| ≥65 | 27.8% | 1.18 (1.14–1.22) | <.001 | ||

| Race | 89.0 | <.001 | |||

| White | 28.1% | Reference | |||

| Black | 25.3% | 0.97 (0.93–1.02) | .268 | ||

| Other | 27.1% | 0.77 (0.73–0.81) | <.001 | ||

| Grade | 6887.4 | <.001 | |||

| I | 63.7% | Reference | |||

| II | 46.4% | 1.38 (1.29–1.46) | <.001 | ||

| III | 26.7% | 1.79 (1.68–1.9) | <.001 | ||

| IV | 29.3% | 1.58 (1.36–1.84) | <.001 | ||

| TNM stage | 20450.4 | <.001 | |||

| I | 71.6% | Reference | |||

| II | 49.9% | 2.47 (2.29–2.65) | <.001 | ||

| III | 26.6% | 3.81 (3.57–4.06) | <.001 | ||

| IV | 7.1% | 7.27 (6.84–7.73) | <.001 | ||

| Surgery | 14212.2 | <.001 | |||

| No | 12.4% | Reference | |||

| Yes | 67.0% | 0.39 (0.37–0.41) | |||

| <0.001 | |||||

| Radiotherapy | 1571.4 | <.001 | |||

| No | 34.6% | Reference | |||

| Yes | 18.3% | 1.08 (1.05–1.12) | |||

| <0.001 | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 1616.5 | <.001 | |||

| No/unknown | 41.0% | Reference | |||

| Yes | 17.5% | 0.63 (0.61–0.65) | |||

| <0.001 | |||||

| Median household income | 144.9 | <.001 | |||

| <3946 | 25.9% | Reference | |||

| 3946–4494 | 26.5% | 0.9 (0.87–0.93) | <.001 | ||

| 4494–5400 | 28.4% | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | .452 | ||

| ≥5400 | 29.8% | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | .372 | ||

| Marital status | 108.3 | <.001 | |||

| Married | 28.3% | Reference | |||

| Divorced | 27.6% | 1.1 (1.05–1.15) | <.001 | ||

| Single | 26.5% | 1.1 (1.05–1.15) | <.001 | ||

| Widowed | 26.9% | 1.21 (1.15–1.26) | <.001 | ||

3.3. Subgroup analysis by sex, cancer grade, and TNM stage

We further investigated the prognostic effect of marital status according to sex, cancer grade, and TNM stage using log-rank tests and the Cox regression analysis. Widowed patients had the worse 5-year CSS in both sexes, and widowed men had the worst 5-year CSS (Supplementary Figure 1). Cox regression analyses indicated that widowed patients had a greater risk of cancer-specific mortality compared with their married counterparts (P < .001) regardless of sex. The prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma varied according to cancer grade. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, married patients had the highest 5-year CSS for all cancer grades, and widowhood was identified as an independent risk factor (Supplementary Figure 2, P < .05). Similarly, widowed patients had the worst 5-year CSS in all TNM stage subgroups, and marital status was significantly related to CSS (Supplementary Figure 3). In contrast to married patients, widowed patients had significantly lower 5 year-CSS in the TNM I, TNM III, and TNM IV groups but not in TNM stage II patients (Supplementary Table 1).

4. Discussion

The study revealed that marital status may be an independent prognostic factor in patients with lung adenocarcinoma, with and 5 year CSS in married patients were higher than divorced, widowed, and single patients, regardless of sex, cancer grade, and TNM stage.

Our key findings are in line with previous reports with other types of cancer.[10,13–15] Several hypotheses have been proposed to elucidate the poorer prognosis in widowed patients. One possible cause may be the undertreatment for this situation. Zhou et al[16] similarly found that widowed patients with gastric cancer were more likely to decline the surgery. Undertreatment may be attributed to the lack of required support from a spouse, and a lack of financial resources, given that spousal support can assist with activities of daily living,[17] compliance with the prescribed treatment protocol, and receiving medical assistance.[17–19] In addition, married patients with more financial resources are more likely to access medical care for early detection and timely and advanced treatment.[20–22] A lack of these advantages thus means that widowed patients are prone to undertreatment. Low adherence to the prescribed treatments may also be a factor. Cohen et al[23] found that unmarried patients always had poorer adherence to treatments than married patients. In breast cancer patients, a low compliance rate to tamoxifen was related to an increased risk of death,[24] and delayed or missed radiotherapy increased the risk of locoregional recurrence and death in patients with head/neck cancers.[25] Psychological support is also an important factor. People diagnosed with cancer may suffer from depression, anxiety, and psychosocial distress,[26] which are deleterious to the endocrine and immune systems.[27] Immune dysfunction may in turn lead to a decrease of natural-killer cell cytotoxicity,[28] while endocrine dysfunction affects the secretion of catecholamines and cortisol.[28,29] These mechanisms may accelerate cancer development and metastasis.[30] Furthermore, a significant decrease in medical compliance was observed in patients with clinical depression,[31] and psychological support was shown to improve the prognosis among married patients by having a spouse to help fight against negative emotions and provide social supports strongly.[22,32,33] In the current study, after controlling the treatment variables including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, we could not distinguish if patients received standard of care or not and exclude the effect of treatment. Therefore, inadequate treatment is still a possible reason for the poor survival of unmarried patients.

In accordance with the previous research,[4] the current study also showed that male patients had a poorer prognosis. Further analysis of the effect of marital status on CSS showed that widowed male patients had the worst 5-year CSS. This may be because, although both sexes suffer from the loss of a spouse, men are subsequently more prone to develop depressive symptoms.[22,32,33]

Numerous studies[4–6,34] have analyzed the relationship between marital status and NSCLC, but none have focused on lung adenocarcinoma. Treatment for patients with NSCLC varies according to pathological type, which may affect the results. However, the present study only enrolled patients with lung adenocarcinoma. In addition, we further investigated the prognostic effect of marital status according to sex, which has not been examined in previous studies, and analyzed a larger sample size (61,928 eligible patients) over a longer period (2004–2016).

This study had some limitations. First, it was a retrospective study with clear inherent limitations. Second, some important confounding variables that could not be obtained from the SEER database such as smoking habits, complications, and cancer-targeted therapy, and other details on treatment. Third, marital status is documented at diagnosis, but it may change in the follow-up. In addition, the database does not contain psychosocial distress measurement which may be linked to the prognosis of patients.

5. Conclusions

The study demonstrates the marital status seems to be an independent prognostic factor in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Compared with married patients, widowed, divorced, or single patients showed a significantly higher risk of cancer-specific mortality. These results highlight the importance of providing adequate psychological and social support for cancer patients, especially unmarried patients.

Author contributions

(I) Conception and design: Ying Wu, Peizhen Zhu, Lu Xu

(II) Administrative support: Ying Wu, Peizhen Zhu, Lu Xu

(III) Provision of study materials or patients: Ying Wu, Yinqiao Chen, Huayi Zhang

(IV) Collection and assembly of data: Ying Wu, Yinqiao Chen, Huayi Zhang

(V) Data analysis and interpretation: Ying Wu, Peizhen Zhu, Jie Chen

(VI) Manuscript writing: All authors

(VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Conceptualization: Ying Wu, Pei-Zhen Zhu, Lu Xu.

Data curation: Ying Wu.

Formal analysis: Ying Wu, Jie Chen.

Investigation: Ying Wu, Lu Xu.

Methodology: Ying Wu.

Project administration: Pei-Zhen Zhu, Huayi Zhang.

Resources: Ying Wu, Pei-Zhen Zhu, Yin-Qiao Chen, Huayi Zhang.

Software: Jie Chen.

Supervision: Ying Wu, Yin-Qiao Chen.

Visualization: Ying Wu.

Writing – original draft: Ying Wu, Pei-Zhen Zhu, Yin-Qiao Chen.

Writing – review & editing: Ying Wu, Pei-Zhen Zhu, Yin-Qiao Chen, Jie Chen, Lu Xu, Huayi Zhang.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CSS = cancer-specific survival, HR = hazard ratio, ICD-O-3 = International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer, SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

How to cite this article: Wu Y, Zhu PZ, Chen YQ, Chen J, Xu L, Zhang H. Relationship between marital status and survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma: a SEER-based study. Medicine. 2022;101:1(e28492).

YW and P-ZZ contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

Values are n (%). According to the quartiles, the median household income variable was divided into 4 groups. Among all patients, the lower quartile, the median, and the upper quartile were 3946, 4494, and 5400, respectively.

CSS = cancer-specific survival.

References

- [1].Gariani J, Martin SP, Hachulla AL, et al. Noninvasive pulmonary nodule characterization using transcutaneous bioconductance: preliminary results of an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Byun J, Schwartz AG, Lusk C, et al. Genome-wide association study of familial lung cancer. Carcinogenesis 2018;39:1135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Li C, Lu H. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Onco Targets Ther 2018;11:4829–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wu Y, Ai Z, Xu G. Marital status and survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of 70006 patients in the SEER database. Oncotarget 2017;8:103518–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Saito-Nakaya K, Nakaya N, Fujimori M, et al. Marital status, social support and survival after curative resection in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci 2006;97:206–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Saito-Nakaya K, Nakaya N, Akechi T, et al. Marital status and non-small cell lung cancer survival: the Lung Cancer Database Project in Japan. Psychooncology 2008;17:869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jatoi A, Novotny P, Cassivi S, et al. Does marital status impact survival and quality of life in patients with non-small cell lung cancer? Observations from the mayo clinic lung cancer cohort. Oncologist 2007;12:1456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mao W, Deng F, Wang D, Gao L, Shi X. Treatment of advanced gallbladder cancer: a SEER-based study. Cancer Med 2020;9:141–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3869–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gao Z, Ren F, Song H, et al. Marital status and survival of patients with chondrosarcoma: a population-based analysis. Med Sci Monit 2018;24:6638–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li Y, Zhu MX, Qi SH. Marital status and survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tannenbaum SL, Zhao W, Koru-Sengul T, Miao F, Lee D, Byrne MM. Marital status and its effect on lung cancer survival. Springerplus 2013;2:504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang F, Xie X, Yang X, Jiang G, Gu J. The influence of marital status on the survival of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Oncotarget 2017;8:51016–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li Q, Gan L, Liang L, Li X, Cai S. The influence of marital status on stage at diagnosis and survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2015;6:7339–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ghazali SM, Othman Z, Cheong KC, et al. Non-practice of breast self examination and marital status are associated with delayed presentation with breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013;14:1141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhou R, Yan S, Li J. Influence of marital status on the survival of patients with gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:768–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Haley WE. Family caregivers of elderly patients with cancer: understanding and minimizing the burden of care. J Support Oncol 2003;1: (4 suppl 2): 25–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 2011;364:514–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Simeonova E. Marriage, bereavement and mortality: the role of health care utilization. J Health Econ 2013;32:33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Inverso G, Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Donoff RB, Chuang SK. Health insurance affects head and neck cancer treatment patterns and outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;74:1241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Parikh AA, Robinson J, Zaydfudim VM, Penson D, Whiteside MA. The effect of health insurance status on the treatment and outcomes of patients with colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2014;110:227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Baine M, Sahak F, Lin C, Chakraborty S, Lyden E, Batra SK. Marital status and survival in pancreatic cancer patients: a SEER based analysis. PLoS One 2011;6:e21052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cohen SD, Sharma T, Acquaviva K, Peterson RA, Patel SS, Kimmel PL. Social support and chronic kidney disease: an update. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2007;14:335–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].McCowan C, Wang S, Thompson AM, Makubate B, Petrie DJ. The value of high adherence to tamoxifen in women with breast cancer: a community-based cohort study. Br J Cancer 2013;109:1172–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pajak TF, Laramore GE, Marcial VA, et al. Elapsed treatment days–a critical item for radiotherapy quality control review in head and neck trials: RTOG report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991;20:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kaiser NC, Hartoonian N, Owen JE. Toward a cancer-specific model of psychological distress: population data from the 2003-2005 National Health Interview Surveys. J Cancer Surviv 2010;4:291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gidron Y, Ronson A. Psychosocial factors, biological mediators, and cancer prognosis: a new look at an old story. Curr Opin Oncol 2008;20:386–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, et al. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:240–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Moreno-Smith M, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. Impact of stress on cancer metastasis. Future Oncol 2010;6:1863–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McEwen BS, Biron CA, Brunson KW, et al. The role of adrenocorticoids as modulators of immune function in health and disease: neural, endocrine and immune interactions. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1997;23:79–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Goldzweig G, Andritsch E, Hubert A, et al. Psychological distress among male patients and male spouses: what do oncologists need to know? Ann Oncol 2010;21:877–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chen Z, Yin K, Zheng D, et al. Marital status independently predicts non-small cell lung cancer survival: a propensity-adjusted SEER database analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2020;146:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.