Abstract

This study explores the association between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation and determines the mediating role of psychological suzhi and the moderating role of perceived school climate. 855 (Nboy = 417, Ngirl = 438; Mage=13.18, SD = .78) students in this study from grade 7 to grade 9 completed questionnaires of the mentioned study variables. The results indicated that bullying victimization positively predicted adolescents’ suicidal ideation. Psychological suzhi partially mediated the effect of bullying victimization on suicidal ideation. However, for adolescents with higher levels of perceived school climate, bullying victimization was correlated more strongly with suicidal ideation and weaker with psychological suzhi. Results meant that the more frequent and more severe the bullying, the higher the likelihood of suicidal ideation among adolescents. Psychological suzhi may act as a potential mechanism through which bullying victimization leads to suicidal ideation, nevertheless, perceived school climate not only buffered bullying victimization’s effects on suicidal ideation, but also protected psychological suzhi from the negative influence of bullying.

Keywords: adolescents, bullying victimization, suicidal ideation, psychological suzhi, perceived school climate

Suicidal ideation refers to the idea and intention of an individual to voluntarily end his life, which is an essential psychological activity in the early stage of suicidal behavior (Zhang, 2005). In China, the largest developing country, about 250,000 people die of suicide every year, and about 2,000,000 attempt suicide, which has become the fifth leading cause of death in China and the first leading cause of death among young Chinese aged 15 to 34 (Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center, 2007). The prevalence of suicidal ideation differed statistically between genders and among grades (Klomek et al., 2009; Laukkanen et al., 2005; Shen & Wang, 2020). Notably, the suicide attempt rate among junior high school students was higher than that among senior high school (Shen & Wang, 2020). The differences in genders and grades are very essential in the study of adolescent suicidal ideation. Therefore, it is important to explore the mechanism of individual and environmental factors that influence the formation of suicidal ideation among junior high school students, which will provide a strong theoretical guidance for future clinical staffs workers to intervene in suicide behavior.

Bullying Victimization and Suicidal Ideation

Bullying refers to a student being hurt over a period of time by repeated negative behaviors from one or more other students (Olweus, 1993). These negative actions can take many forms, including direct physical, verbal bullying, and relational bullying (Olweus, 1993). No singular form of bullying has emerged as the strongest predictor of suicidal ideation (Holt et al., 2015). Research data indicate that youth victimized from bullying are nearly six times more likely to engage in suicidal behaviors than non-victims (Li & Shi, 2018). The Strain Theory of Suicide holds that suicidal ideation mainly originated from the tremendous discordant pressure generated by the individual's perception of the inconsistency between the reality and the desire (Zhang, 2005). Those discordant pressures are divided into four categories: the conflict of different values, the conflict between reality and desire, relative deprivation and the lack of skills to cope with the crisis. Bullying victimization belongs to the last one. If an individual has insufficient ability to deal with their own bullying crisis, he/she will experience the stress of disharmony, and eventually produce suicidal ideation (Olweus, 2013; Zhang, 2005). Therefore, they will develop the uncoordinated pressure and even suicidal ideation (Kaltiala-Heino et al., 1999). Based on the literature reviewed, we hypothesize (H1) the following hypotheses: Bullying victimization was a positive predictor of suicidal ideation.

The Mediating Role of Psychological suzhi

The concept of “Psychology quality” was first devised by Zhang et al. (2000) in China’s quality-oriented education in the 1980s. They defined it as a multi-level self-management system, which derived functions related to the development of adaptive and creative behaviors from basic psychological qualities and apparent adaptive behaviors (Nie, Yang, et al., 2020a; Zhang et al., 2011). Its popularity has risen ramatically with the publication of an international authoritative reference book named the Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools (Furlong et al., 2009). According to the bi-factor (general factors and special factors) model (Holzinger & Swineford, 1937), psychological suzhi consists of cognitive quality, personality quality, and adaptation (Wu et al., 2017).

Specifically, cognitive quality mainly means the psychological qualities related to individuals’ reflection to objective things (eg. perception). It is the most basic element of psychological suzhi. Personality quality is the core element of psychological suzhi and mirrors the personality of an individual. It does not directly involve in decided operations of cognition, but is the inner force that optimizes character, enhances cognitive ability and social adaptation. And adaptation mainly refers to the quality that individuals change themselves or the environment in the process of socialization to make themselves coordinated with the environment. This is a comprehensive representation of cognitive factors and individual factors in an individual's external behavior (Nie, Teng, et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2021).

Zhang et al. conducted a further study on Chinese adolescents’ psychological suzhi and found that it had a positive influence on students’ depression, loneliness, and friendship quality, which were inextricably linked to individual suicidal ideation (Zhang, Su, & Wang, 2017). And there are empirical studies to further prove that psychological suzhi could negatively predict individual suicidal ideation effectively ((Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2021). According to the psychological suzhi formation mechanism sub-model (Zhang & Wang, 2012), the improvement of individual cognitive quality, personality quality, adaptability is greatly affected by the environment (Zhang, Su, & Wang, 2017). However, prior researches have focused more on the influence of family (Parental emotional warmth, Wu et al., 2015; Parental and peer attachment, Pan, Hu, et al., 2017; Socioeconomic status, Luo et al., 2019) on psychological suzhi, and ignored the influence of the campus. Some studies have found that bullying victimization may affect the development of adolescents’ resilience, mental health and other variables which closely related to psychological suzhi (Zhou et al., 2017; Arseneault, 2017; Zhang et al. 2017a).

Moreover, the psychological suzhi functional mechanism sub-model (Zhang & Wang, 2012) pointed out that external risk factors, such as bullying victimization, all need to act through internal psychological suzhi. Therefore, this study believes that bullying experience in school will affect the formation of children's internal psychological suzhi and then exert a significant influence on individual behaviors (He & Zhang, 2019; Li et al., 2016). Therefore, regarding the relationship between bullying victimization, psychological suzhi and suicidal ideation, the present study hypothesized (H2) that psychological suzhi mediated the association between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation.

The Moderating Role of Perceived School Climate

Bullying victimization may lead to higher suicidal ideation among adolescents , but this is certainly not for everyone. By reviewing the previous literature, this study found that perceived school climate is likely to moderate that mediation model (Wasserman et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2016; Li and Shi, 2018). Perceived school climate, a protective factor directly related to school ecology (Thapa et al., 2013), refers to the quality and consistency of interpersonal interactions within the school context that influences children's cognitive, social, and psychological development (Haynes et al., 1997).

The Strain Theory of Suicide (Zhang, 2005) believed that the relationship between the conflict of different values and suicide may be buffered by social factors in the school (Zhang, 2005; Zullig et al., 2010). According to that theory, individual suicidal ideation was influenced by interaction of bullying victimization and perceived school climate. Moreover, many studies found that negative perceived school climate could hinder the adolescents from meeting basic psychological needs and then lead to unbearable psychological distress, such as worthlessness, hopelessness, and so on (Liu et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2014). Those are all risk factors for suicide, namely the negative perceived school climate is much more likely to result in adolescent internal problems (Li et al., 2012). Based on the literature reviewed, this study proposed (H3) that perceived school climate may be a moderating factor in the mechanism of adolescent suicidal ideation.

Perceived school climate is also a protective factor for many psychological variables (Cuadros & Berger, 2016). It is known that the core elements of perceived school climate, such as social support dimensions as teacher-student relationship and peer relationship, are closely related to individual psychological suzhi (Zhang et al., 2019). The cognitive quality, which is shown through cognitive processing (Wang, 2013), determines the degree to which individuals perceive the school climate, that is, under the positive perceived school climate, negative events such as bullying and victimization will have a lower negative impact on psychological suzhi. The positive effect of psychological suzhi on suicidal ideation will be enhanced (Liu et al., 2019). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis (H4): perceived school climate is also a moderated factor in the mediating (psychological suzhi) first half of pathway.

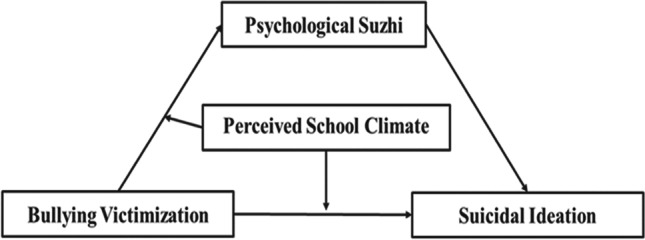

To sum up, based the Strain Theory of Suicide, this study investigated three questions: (1) whether bullying victimization is a risk factor for suicidal ideation in adolescents; (2) whether psychological suzhi mediates the relationship between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation; (3) whether the perceived school climate has a moderating effect on the mediating effect.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

According to the principle of convenience sampling, a total of 925 questionnaires were distributed to the three grades of the two junior middle schools particularly in Zibo city, Shandong Province, and Tongren City, Guizhou Province. Eliminating regular answers and incomplete questionnaires, 855 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective recovery rate of 92.4 percent. The subjects (417 boys; 438 girls; Mage=13.18, SD = .78), including 150 students in Grade 7 (17.5%), 435 students in Grade 8 (50.9%) and 270 students in Grade 9 (31.6%), ranged in age from 13 to 15. Because both middle schools are rural middle schools, most families have a lower economic status and most parents have a lower level of education.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hunan Normal University of China and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from teachers (rate = 100%), parents (rate = 100%), and participants (rate = 100%) before data collection. Before starting the survey, participants were asked to read the instruction first carefully, and make clear the purpose of the test and the way of answering. And then students completed the survey independently within the specified time (about 30 minutes) based on their actual situation. The questionnaires were collected by the host to carry out the data management and analysis afterwards.

Measures

Bullying Victimization

The Chinese version of Delaware Bullying Victimization Scale–Student (DBVS–S) was used to evaluate the degree of bullying victimization (Xie et al., 2018). The self-report scale consists of 18 items used to assess physical , verbal , relational bullying and cyberbullying. According to the findings of Bear et al. (2011), cyberbullying is not included in this study, because it often happens outside the school and has a weak relationship with the campus. Therefore, this study selected 12 items in total as tools to measure the degree of bullying of middle school students. Each item of bullying uses a six-point Likert scale including 1 (Never), 2 (Occasionally), 3 (Once or twice a month), 4 (Once a week), 5 (More than once a week) and 6 (Every day). Bullying was considered to have occurred when subjects selected an item "Once or twice a month" with higher reported scores indicating more severe bullied. In the present study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.946.

Suicidal Ideation

The self-rating scale for suicidal ideation (SIOSS) was used to evaluate the degree of the existence of suicidal ideation (Xia & Wang, 2002). It was compiled by Chinese scholars based on Suicidal Ideation screening Questionnaires used widely in the world. There were 26 items in the scale investigating four factors: optimism, desperation, sleep and dissimulation. The items were scored with "Yes (0)" or "No (1)" responses, and the sum of the scores of the three areas (optimism, despair and sleep) reflected the intensity of suicidal ideation. The higher the scores, the more likely to have suicidal ideation, with scores ≥ 12 indicative of a positive screen for suicidal ideation (Zhang, 1998). The dissimulation score reflects the dependability of the results, and a score ≥ 4 indicates an unreliable result. No participant scored ≥ 4 on this dimension. SIOSS is a widely used scale with good reliability and validity (Xia, 1993). The Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.880.

Psychological suzhi

Psychological suzhi was measured by The Psychological suzhi Scale for Adolescents (the simplified version). The purpose of this scale is to value the positive psychological characteristics that promote Chinese students to actively adapt to the Chinese school environment (Pan, Zhang, & Wu, 2017). It consists of 24 items, divided on an average of three subscales: cognitive quality, personality quality, and adaptability. The scale has good reliability and validity among Chinese adolescents (Wu et al., 2017). Cronbach's α is 0.960 in this study.

Perceived School Climate

Delaware School Climate Scale-Student (DSCS-S) was revised by Chinese scholars (Xie et al., 2016), which contains a total of 36 items and 8 dimensions, namely Teacher–Student Relations, Student–Student Relations, Fairness of School Rules, Clarity of Expectations, Respect for Diversity, School Safety, Engagement Schoolwide and Bullying Schoolwide. Each item assesses the occurrence of bullying using a four-point Likert scale ranged 1 (strongly disagree)-4(strongly agree). The higher the total score was, the better the perceived school climate perceived by students. Cronbach's α is 0.96 for the scale in this study.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis included all the variables of interest for the total sample. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the influence of grade on suicidal ideation, and an independent sample t-test was conducted to examine the gender differences in suicidal ideation. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to ensure that the measurement model of the sample data has an acceptable fit. Then, after controlling for demographic variables such as gender and grade, a structural equation modeling (SEM) was implemented to examine the relationship between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation.

The following indicators were used to evaluate the goodness of fit of the measurement model (Hu & Bentler, 1999): CFI, TLI, RMSEA with 90% confidence interval and normalized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI ≥ 0.90, TLI ≥ 0.90, SRMR ≤ .08, RMSEA ≤ .08 indicate that the model fitting is goodness of fit. LMS analysis was performed by Mplus 8.3 (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2020) to estimate the effects of bullying victimization and potential moderators (i.e., perceived school climate) on suicidal ideation and psychological suzhi. In the total sample with gender and grade were controlled.

Results

Common Method Biases

Harman single factor method was used to test common method variance. The results showed that there were 14 factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1. The variance of the interpretation of the first factor was 26.86%, less than the critical standard of 40%. That indicated that there was no serious common method variance in the data of this study.

Descriptive Analysis

The incidence rate for bullying victimization was at 16.34% and that for suicidal ideation was 9.01%. The results of the ANOVA (in Table 1) showed a significant suicidal ideation of grade, F(2,852) =29.81, p <0.001. Ninth graders reported higher levels of suicidal ideation (M = 6.57, SD = 4.11) than seventh (M = 5.01, SD = 3.33) and eighth (M = 4.54, SD = 2.97) graders. The independent sample t-test results showed that there was no significant difference in gender on suicidal ideation t (853) =–1.61; p = 0.11).

Table 1.

The differences of suicidal ideation and bullying victimization in gender and grade

| N | Suicidal Ideation | Bullying Victimization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Boys | 417 | 5.06±3.69 | 17.35±9.39 |

| Girls | 438 | 5.45±3.39 | 14.99±5.82 | |

| t | –1.61 | 4.44*** | ||

| Grade | Grade 1 | 150 | 5.01±3.33 | 17.20±9.03 |

| Grade 2 | 435 | 4.54±2.97 | 15.91±8.31 | |

| Grade 3 | 270 | 6.57±4.11 | 15.92±6.20 | |

| F | 29.81*** | 1.66 |

***p<0.001

According to the correlation analysis shown in Table 1, there was a significant correlation between suicidal ideation and other variables (bullying victimization, psychological suzhi and perceived school climate) in the model. The correlation matrix, mean and standard deviation of each variable were shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations between study variables

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Suicidal Ideation | 5.26 | 3.54 | 1 | |||||

| 2. Bullying Victimization | 16.14 | 7.85 | 0.38** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Psychological Suzhi | 89.16 | 16.32 | -0.32** | -0.23** | 1 | |||

| 4. Perceived school climate | 146.05 | 21.40 | -0.46** | -0.51** | 0.45** | 1 | ||

| 5.Gender | 1.51 | 0.50 | 0.06 | -0.15** | -0.03 | 0.07* | 1 | |

| 6.Grade | 2.14 | 0.69 | 0.19** | -0.05 | 0.13** | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1 |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01

Effects of Bullying Victimization on Suicidal Ideation

According to the test steps of mediating effect (Wen & Ye, 2014), we first established a simple regression model with latent variables to test the direct predictive effect of bullying victimization on suicidal ideation of adolescents. The model showed an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 = 1093.72, df = 368, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = .05, SRMR= .05). After controlling for gender and age, bullying victimization had a significant positive predictive effect on suicidal ideation in adolescents (β= 0.47, p < .001) (Fig. 1).

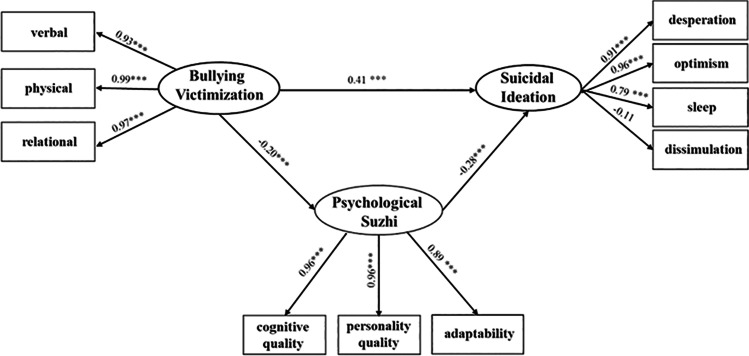

Fig. 1.

The proposed moderated mediation model

Mediated Effect of Psychological suzhi

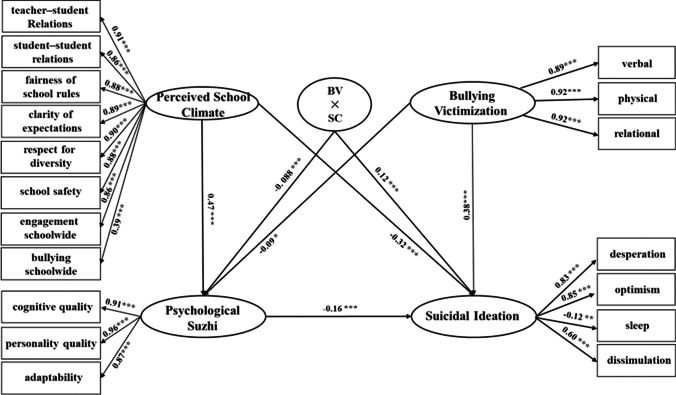

Then, psychological suzhi was added as a mediating variable in this model to construct a simple mediating model. The model fitted well (χ2 = 2169.94, df = 846, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = .004, SRMR = .005). It could be seen from Fig. 2 that the path coefficient between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation among adolescents decreased (0.41), but it was still significant. The mediating effect of psychological suzhi was significant. The indirect effect of the mediating variable was tested by bootstrap method. The estimated indirect effect was .054, and the 95% confidence interval was [.012, .035], which did not include 0, accounting for 11.49% of the total effect. It means that psychological suzhi partially mediated the relationship between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation.

Fig. 2.

The mediation model of bullying victimization and suicidal ideation. Note. Factor loading is standardized. ***p < 0.001

Moderated Effects of Perceived School Climate

Referring to the test steps of the moderated mediation model (Maslowsky et al., 2014; Wen & Ye, 2014), the LMS analysis was used to test the moderating effect of latent variables, perceived school climate.

Firstly, the moderating effect of perceived school climate on the direct effects of bullying victimization and suicidal ideation was examined. In the simple regression model with latent variables, the perceived school climate was added as an independent variable to establish a restricted model. The model fitted well (χ2 = 505.299, df =115, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .05) and LogLrestricted = -24492.925. A potential interaction (perceived school climate × bullying victimization) was added into the restricted model to contruct a full model. The results showed that LogLfull =-24476.688. According to the calculation formula, LR = 32.474, df =1, p < .005, indicating that the full model fitted well. Moreover, the effect of latent interaction was significant (β =0.13, p < .001), indicating that perceived school climate could moderate the influence of bullying victimization on suicidal ideation among adolescents.

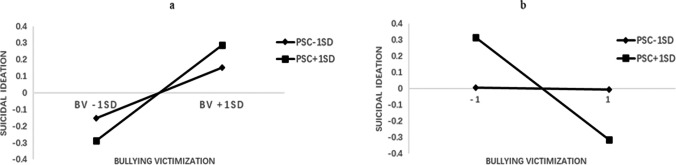

Secondly, it examined the moderated effect of perceived school climate on indirect (i.e., mediated) pathways between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation. The restricted model fitted well (χ2 = 384.416, df = 100, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .04) and LogLrestricted = -26411.321. The results of full model showed that LogLfull = -26404.822. According to the calculation formula, LR =16.998, df =1, p < .01, indicating that the full model fitted well. It could be seen from Fig. 3 that psychological suzhi had a significant negatively predictive effect on suicidal ideation (β = -.089, p < .05), although the latent interaction between perceived school climate and bullying victimization still significantly negatively predicted psychological suzhi (β = .088, p < .001). These results indicated that perceived school climate had a protective effect on the negative effect of bullying victimization on psychological suzhi.

Fig. 3.

The moderated mediation model of bullying victimization and suicidal ideation. Factor loading is standardized. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.***p < 0.001

In order to further reveal the moderating effect of perceived school climate, a simple slope test was conducted on the interaction (perceived school climate × bullying victimization). As shown in Fig 4a, with the decrease of perceived school climate level, the regression slope of bullying victimization to suicidal ideation was always significant but significantly decreased (β = 0.29, p < .001; β= 0.15, p < .001). This showed that the impact of bullying victimization on suicidal ideation was especially significant in adolescents who had high levels of perceived school climate. With low levels of perceived school climate (M-SD), the significance decreased. The Fig 4b showed that with the decrease of perceived school climate level, the regression coefficient of bullying victimization on psychological suzhi gradually decreased until it was not significant (β = -0.314, p < .05; β = -.006, p > .05). This showed that the impact of bullying victimization on psychological suzhi was especially pronounced in adolescents who had low levels of perceived school climate. With high levels of perceived school climate (M+SD), the influence of bullying victimization on the psychological suzhi was no longer significant. The scores of suicidal ideation and psychological suzhi were respectively drawn when perceived school climate was plus or minus one standard deviation (Fig 4).

Fig. 4.

Interactions between bullying victimization and school climate in the prediction of suicidal ideation (a) and psychological suzhi (b), respectively. BV=bullying victimization; SC=school climate

Discussion

Based on the strain theory of suicide, the current study explored the effect of bullying victimization on suicidal ideation and its underlying mechanism of the mediating and protective processes.

Beforehand, this study examined the effects of demographic factors on suicidal ideation. Girls reported slightly more but not significantly different suicidal ideation than did boys, which was partly consistent with previous studies (Qi et al., 2020; Zhang, Liu, & Sun, 2017). However, boys experienced more bullying victimization than did girls, which perhaps indicated that girls are more likely to internalize their problems (Wu et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2014). On the other hand, this result also supported Hyde's (2005) the gender similarity hypothesis that male and female were more similar than different in most psychological phenomena. Regarding grade differences, which was consistent with previous research (Qi et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2017), students in Grade 3 reported the highest suicidal ideation compared with other grades. Studies have pointed that the rate of suicidal ideation among adolescents began to rise in early adolescence and reached a peak in mid-adolescence (Kessler et al., 1999). It may be associated that the students in Grade 3, facing the high school entrance examination had heavier pressure from education and family (Zhu et al., 2017).

Bullying Victimization and Suicidal Ideation

This study, in a large sample of Chinese adolescents, believed that bullying victimization could effectively negatively predict suicidal ideation, meaning individuals being bullied were more likely to suffer from suicidal ideation. This finding Verified hypothesis 1 and was consistent with the Strain Theory of Suicide and the existing studies (Baiden & Tadeo, 2020; Barzilay et al., 2017; Cao et al., 2020; Herba et al., 2008; Moore et al., 2017). Students in middle school who are often intimidated and ridiculed by their peers may experience serious uncoordinated pressure (Zhang, 2005). When an individual's coping ability was unable to resist the crisis, the uncoordinated pressure would lead to emotional adaptation or internalization problems such as anxiety, despair and depression, and eventually suicidal ideation (Zhang, 2005). Bullying leaded to the power imbalance between the perpetrators and the targets, so the targets lacked the ability to cope with such imbalance or even crisis and could not protect himself (Olweus, 2013). Individuals being bullied would be forced to withdraw from the mainstream social group and be marginalized in the peer group (Ji et al., 2011; Koo, 2007; Li, 2016; Liu et al., 2015).

The Mediating Role of Psychological suzhi

Moreover, the results of total sample data reported that psychological suzhi had a significant partial mediating effect between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation. The findings supported our hypothesis 2. From the perspective of the relationship between psychological suzhi and mental health, psychological suzhi lied at the core of psychological structure and had a decisive influence on mental health, which was the explicit level of mental structure (Wang et al., 2011; Wang & Zhang, 2012). On the one hand, the results were consistent with the psychological suzhi and formation and function mechanism sub-model, which was determined by the interaction between innate genetic factors and acquired environmental factors and greatly influenced by external environmental stimulation and social adaptation (Zhang & Wang, 2012). Adolescence was the key period for the development of their psychological suzhi, which was vulnerable to stressful events such as being bullied and victimized (Zhang & Wang, 2020). On the other hand, the results confirmed to the resource conservation theory and believed that individuals with more personal resources showed greater ability to reduce stress (Hobfoll, 2001). However, being bullied leaded individuals to have unhealthy psychological status and insufficient personal resources (low psychological suzhi) thus reducing the ability to relieve stress (Wu et al., 2018).

The Moderated Role of Perceived School Climate

Consistent with the hypothesis 3 and 4, it also found that the influence of bullying victimization on the suicidal ideation and psychological suzhi was moderated by the perceived school climate. It showed that the perceived school climate buffered the negative effects of bullying victimization.

Firstly, perceived school climate could moderate the relationship between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation, which was consistent with the strain theory of suicide. Compared with students with low perception of perceived school climate, individuals with high perception of perceived school climate had relatively fewer suicidal ideation when they were bullied. This indicated that a positive perceived school climate could play a protective role in preventing violence, especially bullying victimization. For adolescents, school has become their main environmental factor, and the intimate relationship with parents has gradually been replaced by that with peers (Nickerson & Nagle, 2019). As mentioned in previous studies, a positive perceived school climate greatly reduced the adverse psychological outcomes of adolescents (Birkett et al., 2009). Some researchers believed that a positive perceived school climate could provide a "safe haven" for "high-risk individuals" facing bullying, emotional and behavioral difficulties. It meant that perceived school climate played a protective role in promoting their healthy development and also inhibited their negative emotions and problem behaviors (Coker & Borders, 2001).

Secondly, perceived school climate could moderate the relationship between bullying victimization and psychological suzhi. Compared with students with low perceived school climate perception, individuals with high perceived school climate perception had less resistance to psychological suzhi development when they are bullied. Previous studies have pointed out that a positive perceived school climate could both protect negative factors and positively promote the development, healthy growth and academic performance of adolescents (Thapa et al., 2013). Positive perceived school climate can improve adolescents’ school adjustment and then buffer the negative impact of bullying (Liu et al., 2019). From the perspective of ecosystem theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1989), the positive perceived school climate reflected the harmonious relationship between individuals and various micro-systems to some extent. It would inevitably promote the development of individual cognition, the formation of personality and great social adaptability, thus alleviating the negative impact of bullying victimization on psychological suzhi. Some researchers believed that the positive perceived school climate significantly affected the mental health of individuals (Moore et al., 2018).

Study Limitations

Limited by the research conditions, this study adopted a cross-sectional study, and the research data were all from the self-report of the subjects. Firstly, the cross-sectional study cannot explore the development trend of the core variable and determine the causal relationship among those variables. Therefore, this field can obtain long-term longitudinal data sets that adopt multi-informant approaches future. Secondly, the results from self-report showed that there was no serious common method variance problem, but it is impossible to exclude entirely the serious error problem caused by the single data collection method. Of course, experiments or follow-up studies are still needed in the future to further clarify the cause-effect relationship among the variables.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Research

Therefore, symptoms of distress manifested by victims of bullying would be normative and may not require intervention (Arseneault et al., 2010). But we still carried out some psychological counseling to those who reported suicidal ideation in this study. Understanding the association between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation could contribute to early identification of adolescents who may be at risk for suicide. The findings also suggested that it was of potential value to focus on cultivating students' psychological suzhi and improving their perception of school climate in order to reduce the negative impacts of bullying victimization on suicidal ideation. Those are our contributions to provide evidence for further intervention. Furthermore, as far as we know, this is the first empirical study on the concept of positive psychology (psychological suzhi) with perceived school climate as a protective factor, which verifies psychological suzhi function mechanism sub-model.

Practically, first of all, educators should be alert to whether the rate of bullying is increasing among adolescents, and pay great attention to the negative impacts of bullying on adolescent’s mental health outcomes. Secondly, it is of great significance to identify high-risk adolescents according to the findings of relevant demographic factors and multi-group analysis. For example, more attention should be paid to those students who are about to face the college entrance examination (Grade 9). Thirdly, considering the role of perceived school climate and psychological suzhi in the relationship between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation among adolescents, the results of this study can remind educators and caregivers that timely intervention is crucial for cultivating and improving the psychological suzhi and perceived school climate of bullied adolescents.

At last, if adolescents’ suicidal ideation could not be eliminated they might need to consult clinical psychologists, therapists, and counselors. After all, nearly every school provides psychological support services (e.g., school psychologists, etc.).

Conclusion

The present study concluded that bullying victimization positively predicted adolescents’ suicidal ideation. Psychological suzhi partially mediated the effect of bullying victimization on suicidal ideation. And for adolescents with higher levels of perceived school climate, bullying victimization was correlated more strongly with suicidal ideation and weaker with psychological suzhi. Moreover, the current study expanded our understanding of underlying theoretical mechanism of the effect of bullying victimization on suicidal ideation in adolescents by exploring the mediating role of psychological suzhi and the moderating role of perceived school climate. Furthermore, the results of this study provide practically evidence support and specific advice for clinical intervention of suicidal ideation in adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the study on the construction of psychological assistance model and multiple interventions for disabled children in Hunan Province (grant number: XJK20AXL01), practice research on the innovation of teaching idea in the reform of postgraduate teacher education in local normal university (grant number: 2019JGZX005), an intervention study on anxiety of left-behind children in Hunan Province based on mindfulness therapy (grant number: 18A029), and research on rural social readjustment and response system of returning migrant workers in Hunan Province (grant number: XSP18YBC324). We thank all the participants in this study. Furthermore, none of this would have been possible without the help of those individuals and organizations hereafter mentioned with gratitude:Xia Feifei, the teacher of Tangqiao Junior High School in Tongren City, Guizhou Province and Li Cuixia and other teachers of Zibo High-Experimental Middle School in Shandong Province, for their hard work on collecting data.

Data

The [DATA TYPE] data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Data Sharing and Declaration

This manuscript’s data will not be deposited.

Author Contributions

GC and LZ designed and coordinated the study; GC and XD carried out experiments and data process; GC, MC and LZ drafted the manuscript; HY reviewed the manuscript. All authors gave the final approval for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by

• the study on the construction of psychological assistance model and multiple interventions for disabled children in following institute in Hunan Province (grant number: XJK20AXL01);

• Practice research on the innovation of teaching idea in the reform of postgraduate teacher education in local normal university (grant number: 2019JGZX005);

• An intervention study on anxiety of left-behind children in Hunan Province based on mindfulness therapy (grant number: 18A029);

• Research on rural social readjustment and response system of returning migrant workers in Hunan Province (grant number: XSP18YBC324).

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the Research Ethics Committee of the Hunan Normal University of China and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2020). Bayesian estimation of single and multilevel models with latent variable interactions. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 1–15.

- Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems:'Much ado about nothing'? Psychological medicine. 2010;40(5):717. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L. The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World psychiatry. 2017;16(1):27. doi: 10.1002/wps.20399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiden P, Tadeo SK. Investigating the association between bullying victimization and suicidal ideation among adolescents: Evidence from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Child abuse & neglect. 2020;102:104417. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilay S, Klomek AB, Apter A, Carli V, Wasserman C, Hadlaczky G, Wasserman D. Bullying victimization and suicide ideation and behavior among adolescents in Europe: A 10-country study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;61(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear GG, Gaskins C, Blank J, Chen FF. Delaware school climate Survey-Student: Its factor structure, concurrent validity, and reliability. Journal of School Psychology. 2011;49(1):157–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center (2007). The situation and countermeasures of suicide in China. Retrieved May 8th, 2021, from http://www.docin.com/p-19726436.html?qq-pf-to=pcqq.discussion

- Birkett M, Espelage DL, Koenig B. LGB and questioning students in schools: The moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:989–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. In: Vasta R, editor. Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues. CT L JAI Press; 1989. pp. 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q, Xu X, Xiang H, Yang Y, Peng P, Xu S. Bullying victimization and suicidal ideation among Chinese left-behind children: Mediating effect of loneliness and moderating effect of gender. Children and youth services review. 2020;111:104848. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coker JK, Borders LD. An analysis of environmental and social factors affecting adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2001;79(2):200–208. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01961.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadros O, Berger C. The protective role of friendship quality on the wellbeing of adolescents victimized by peers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45(9):1877–1888. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong MJ, Gilman R, Huebner ES. Handbook of positive psychology in schools. Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes NM, Emmons C, Benavie M. School climate as a factor in student adjustment and achievement. Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation. 1997;8(3):321–329. doi: 10.1207/s1532768xjepc0803_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Zhang DJ. Effects of psychological Suzhi on problem behaviors among freshmen of middle schools and high schools: The mediating role of loneliness and security. Journal of Southwest University (Social Sciences Edition) 2019;41(2):46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Herba CM, Ferdinand RF, Stijnen T, Veenstra R, Oldehinkel AJ, Ormel J, Verhulst FC. Victimisation and suicide ideation in the TRAILS study: specific vulnerabilities of victims. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(8):867–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology. 2001;50(3):337–421. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MK, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Polanin JR, Holland KM, DeGue S, Matjasko JL, et al. Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e496–e509. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzinger KJ, Swineford F. The bi-factor method. Psychometrika. 1937;2(1):41–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02287965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS. The gender similarity hypothesis. American Psychologist. 2005;60(6):581–592. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji LQ, Chen L, Xu FZ, Zhao SY, Zhang WX. A longitudinal analysis of the association between peer victimization and patterns of psychosocial adjustment during middle and late childhood. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2011;43(10):1151–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpela M, Marttunen M, Rimpela A, Rantanen P. Bullying, depression, and suicidal ideation in finnish adolescents: school survey. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:348–351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7206.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of general psychiatry. 1999;56(7):617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomek AB, Sourander A, Niemelä S, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: a population-based birth cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(3):254–261. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318196b91f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo HA. Time line of the evolution of school bullying in differing social contexts. Asia Pacific Education Review. 2007;8(1):107–116. doi: 10.1007/BF03025837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen E, Honkalampi K, Hintikka J, Hintikka U, Lehtonen J. Suicidal ideation among help-seeking adolescents: association with a negative self-image. Archives of Suicide Research. 2005;9(1):45–55. doi: 10.1080/13811110590512930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DP, Bao ZZ, Li X, Wang YH. Perceived school climate and Chinese adolescents’ suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: The mediating role of sleep quality. Journal of School Health. 2016;86(2):75–83. doi: 10.1111/josh.12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DP, Zhang W, Li X, Li NN, Ye BJ. Gratitude and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: Direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35(1):55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YJ. Victimization and suicide in adolescents: Mediating effect of depression and its gender difference. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2016;24(2):282–286. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Shi JR. Bullying and suicide in high school students: Findings from the 2015 California youth risk behavior survey. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2018;28(6):1–15. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2018.1456389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GZ, Pan YG, Li BB, Hou XL, Zhang DJ. The protective effect of psychological suzhi on the relationship between school climate and alcohol use among Chinese adolescents. Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 2019;12:307–315. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S202127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XQ, Chen G, Yang XH, Lu DL, Zhou LH, Su LY. The moderating effect of social support on bullying and suicidal ideation in junior high school students. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2015;36(9):1410–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Luo S, Liu Y, Zhang D. Socioeconomic status and young children’s problem behaviours–mediating effects of parenting style and psychological suzhi. Early Child Development and Care. 2019;191(1):148–158. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2019.1608196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Jager J, Hemken D. Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2014;39(1):87–96. doi: 10.1177/0165025414552301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore H, Benbenishti R, Astor RA, Rice E. The positive role of school climate on school victimization, depression and suicidal ideation among school-attending homeless youth. Journal of School Violence. 2018;17(3):1538–8239. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2017.1322518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, Thomas HJ, Sly PD, Scott JG. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):60–76. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson AB, Nagle RJ. Parent and peer attachment in late childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2019;25(2):223–249. doi: 10.1177/0272431604274174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Q, Yang CY, Teng ZJ, Furlong MJ, Pan YG, Guo C, et al. Longitudinal association between school climate and depressive symptoms: The mediating role of psychological suzhi. School Psychology. 2020;35:267–276. doi: 10.1037/spq0000374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Q., Teng, Z. J., Yang, C. Y., Lu, X. Y., Liu, C. X., Zhang, D. J., et al. (2020b). Psychological suzhi and academic achievement in chinese adolescents: A 2-year longitudinal study. The British Journal of Educational Psychology. e12384. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Olweus D. Bullying at School:What We Know and What We Can Do? Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9(1):751–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan YG, Zhang DJ, Wu LL. The Development of the brief psychological suzhi questionnaire for primary school students. Journal of Southwest University (Social Sciences Edition) 2017;43(2):127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Hu Y, Zhang D, Ran G, Li B, Liu C, Chen W. Parental and peer attachment and adolescents' behaviors: The mediating role of psychological suzhi in a longitudinal study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;83:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.10.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi JD, Hunag DW, Liu X, Ying TZ. The Status of suicidal ideation and the role of networking self-efficacy and loneliness among junior middle school students. Chinese Journal of Health Education. 2020;05:450–454. [Google Scholar]

- Shen JX, Wang Y. Suicide attempts in Chinese mainland middle school students with suicidal ideation: A meta-analysis between 2009 and 2018. Modern Preventive Medicine. 2020;47(12):2206–2210. [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Xia TS, Reece C. Social and individual risk factors for suicide ideation among Chinese children and adolescents: A multilevel analysis. International Journal of Psychology. 2016;53(2):117–125. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa A, Cohen J, Guffrey S, HigginsD’Alessandro A. A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research. 2013;83(3):357–385. doi: 10.3102/0034654313483907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Q. (2013). A research on relationship model between adolescents’ psychological suzhi and mental health: The theory construction and empirical research. Doctoral Dissertation. Southwest University.

- Wang XQ, Zhang DJ, Wang JL. Dual-factor model of mental health: Surpass the traditional mental health model. Psychology. 2011;2(08):767. doi: 10.4236/psych.2011.28117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XQ, Zhang DJ. Looking beyond PTH and DFM: The relationship model between psychological Suzhi and mental health. Journal of Southwest University (Social Sciences Edition) 2012;38(6):67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman D, Rihmer Z, Rujescu D, Sarchiapone M, Sokolowski M, Titelman D, Zalsman G, Zemishlany Z, Carli V. The European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on suicide treatment and prevention. European Psychiatry. 2012;27(2):129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen ZL, Ye BJ. Mediating effect analysis: Methods and model development. Advances in Psychological Science. 2014;22(5):731–745. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.00731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LL, Zhang DJ, Cheng G. Preliminary study on bifactor structure of primary and secondary students’ psychological quality. Studies of Psychology and Behavior. 2017;15(1):26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LL, Zhang DJ, Cheng G, Hu TQ. Bullying and social anxiety in Chinese children: Moderating roles of trait resilience and psychological Suzhi. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2018;76:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Zhang D, Cheng G, Hu T, Rost DH. Parental emotional warmth and psychological Suzhi as mediators between socioeconomic status and problem behaviours in Chinese children. Children and Youth Services Review. 2015;59:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia ZY, Wang DB. Revision of Suicidal Ideation of Self-rating Scale (SIOSS) Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;12(2):100–102. [Google Scholar]

- Xia ZY. The Suitability Assessment for Lie Scale. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993;8(3):41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Xie JS, Wei YM, Bear GG. Revision of Chinese version of Delaware Bullying Victimization Scale-student in adolescents. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2018;26(2):259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Xie JS, Lv YX, Ma K, Xie L. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Delaware School Climate Survey-Student. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2016;24(2):250–253. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DJ, Feng ZZ, Guo C, Chen X. Problems on research of children’s psychological suzhi. Journal of Southwest China Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences Edition) 2000;26:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DJ, Wang JL, Yu L. Methods and implementary strategies on cultivating students’ psychological suzi. Nova Science Publishers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DJ, Wang XQ. An analysis of the relationship between mental health and psychological suzhi: From the perspective of connotation and structure. Journal of the Southwest University (Social Science Edition) 2012;38(3):69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DJ, Su ZQ, Wang XQ. Thirty-years study on the psychological quality of Chinese children and adolescents: Review and prospect. Studies of Psychology and Behavior. 2017;15(1):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GZ, Liang ZB, Deng HH, Lu ZH. Relations between perceptions of school climate and school adjustment of adolescents: A longitudinal study. Psychological Development and Education. 2014;30(4):371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Conceptualizing a strain theory of suicide (review) Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2005;19(11):778–782. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Liu Y, Sun L. Psychological strain and suicidal ideation: A comparison between Chinese and US college students. Psychiatry research. 2017;255:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang MY. Psychiatric rating scale manual. Second Edition. Hunan science & technology press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Wang Z. The effects of family functioning and psychological Suzhi between school climate and problem behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:212. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XQ, Zhang DJ, Lin YH, Nie Q, Wang XQ, Wu LL, Lu XY. The relationship between psychological Suzhi and suicidal ideation in adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Southwest University (Social Sciences Edition) 2019;41(6):51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Zhang X, Du JZ, Zheng X. Relationship between social support and depression, loneliness of migrant children: Resilience as a moderator and mediator. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;22(3):512–521. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZK, Liu QQ, Niu GF, Sun XJ, Fan CY. Bullying victimization and depression in Chinese children: A moderated mediation model of resilience and mindfulness. Personality and individual differences. 2017;104:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q, Xia QH, Yu Y, Zhou P, Yu L, Jiang Y. Analysis on prevalence of suicide ideation and its related factors among junior school students. Chinese Journal of School Health. 2017;11:1637–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Tang W, Liu G, Zhang D. The effect of psychological suzhi on suicide ideation in Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of family support and friend support. Frontiers in psychology. 2021;11:4090. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.632274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zullig HJ, Koopman TM, Patton JM, Ubbes VA. School climate: Historical review, instrument development, and school assessment. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2010;28:139–152. doi: 10.1177/0734282909344205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]