Abstract

Promoting the psychosocial flourishing of emerging adults is crucially important. The tendency to feel awe, as captured by dispositional awe, may be a protective factor that promotes psychosocial flourishing. Inspired by the broaden-and-build theory, the present study sought to investigate the underexplored relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing among emerging adults by establishing a dual-mediated model, which focuses on an intrapersonal mechanism of meaning in life and an interpersonal mechanism of social connectedness. Data were collected from a cross-sectional sample of 1213 Chinese emerging adults who completed a series of anonymous questionnaires regarding dispositional awe, psychosocial flourishing, meaning in life, and social connectedness. Results of the correlation analysis revealed positive and significant associations among dispositional awe, meaning in life, social connectedness, and psychosocial flourishing. Structural equation modeling demonstrated that meaning in life and social connectedness fully mediated the association between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing. The mediation effect of meaning in life was stronger than that of social connectedness. These findings contributes to the science of flourishing by identifying the internal mechanisms of why dispositional awe promotes the psychosocial flourishing of emerging adults.

Keywords: Emerging adults, Dispositional awe, Psychosocial flourishing, Meaning in life, Social connectedness

Introduction

Contemporary social development makes the transition to adulthood more complex than ever (Wood et al., 2018). As a major force in promoting social vitality, emerging adults are in a unique period of life that occurs between adolescence and adulthood (Arnett, 2015), which is arguably the most turbulent times in life with many tradeoffs and choices, frequent and rapid lifestyle changes, and the greatest vulnerability to mental health and behavioral challenges (Arnett, 2014; Arnett et al., 2014; Sofija et al., 2021). Compared with young adults in their thirties, most emerging adults have not yet established a stable adult life structure (Arnett et al., 2014). The exploration of a new life can be exciting but are often daunting and confusing to the person, especially for emerging adults who are experiencing struggles and often suffer from depression and anxiety (Arnett et al., 2014; LeBlanc et al., 2020; Wood et al., 2018). For example, the report on National Mental Health Development in China (2019–2020) reveals that emerging adults are the most anxious group, ranking first among all age groups in terms of mental stress (Fu et al., 2021). Therefore, to better support the healthy transition of emerging adults into adulthood and prevent them from getting lost in the transition, it is necessary to explore ways to promote their adaptive development and achieve psychosocial flourishing.

Psychosocial flourishing signifies the positive development of emerging adults (De la Fuente et al., 2020). It does not simply mean seeking to maximize one’s pleasure and minimize one’s pain, but to make all aspects of life develop positively and blossom fully (Danvers et al., 2016). Psychosocial flourishing is a broad concept that reflects an overall view of a good life and refers to an optimal, sustained sense of well-being (Diener et al., 2010). It describes positive human functioning from a comprehensive perspective: meaning and purpose, competence, engagement, self-acceptance, supportive relationships, optimism, well-being of others, and being respected (Diener et al., 2010; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Tang et al., 2016). Psychosocial flourishing is the epitome of mental health and a factor in actively fighting mental disorders (Keyes et al., 2010). It is associated with a range of adaptive indicators, including lower rates of depression and anxiety, greater resilience to life’s vulnerabilities and challenges, higher productivity, stronger creative skills, and more prosocial behaviors (Conner et al., 2016; Huppert, 2009; Moradi et al., 2018; Peter et al., 2011). Despite the increasing interest in psychosocial flourishing (Diener et al., 2010), only limited studies to date have explored the predictors of this notion (Abid et al., 2018). Taking these into account, it is of great significance to investigate the factors that promote emerging adults in the transition period to achieve psychosocial flourishing.

Sustainable psychosocial flourishing may be the result of stability in dispositional traits. As Diener (1984) concluded, dispositional traits are one of the strongest predictors of well-being. Of the dispositional variables, the antecedent role of dispositional awe—a relatively permanent emotional disposition—in predicting psychosocial flourishing has not been fully explored. Researchers on positive psychology have proposed that awe, as a character strength, can help to bring abundant gratification and authentic and sustainable well-being to individuals (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seligman, 2004). An increasing number of evidence suggests that dispositional awe is beneficial to people’s positive functioning across the various aspects of life, such as life meaning and purpose, social relationships, physical and mental health, and well-being of others (Chirico & Gaggioli, 2021; Danvers et al., 2016; Piff et al., 2015; Prade & Saroglou, 2016; Stellar et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018, 2019). We thus posit that dispositional awe may play a stable protective role in promoting psychosocial flourishing. Given that psychosocial flourishing is conducive to the growth of emerging adults, an empirical investigation on the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing would also be helpful to further the understanding of the social functions of dispositional awe. Accordingly, the first purpose of this study is to go beyond previous research by examining the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing in emerging adulthood.

Furthermore, scant attention has been given to the underlying mechanisms and processes through which this relationship occurs. Hence, the second but more important purpose of this study is to further probe into the mediating mechanisms that underlie the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing. Our study is designed to address this issue by using Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson et al., 2008) to develop a dual mediation assumption linking dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing through meaning in life and social connectedness (the hypothetical model is set out in Fig. 1). Clarifying the internal mechanisms of dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing is important—theoretically and practically—in the intervention of promoting the positive and sustainable development of emerging adults.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model

Dispositional Awe and Psychosocial Flourishing

Dispositional awe refers to the chronic tendency to experience awe in general (Shiota et al., 2006). It is a personality trait that reflects an overall pattern of one’s awe response (Shiota et al., 2006), meaning some people are more inclined to experience awe than others (Dong & Ni, 2020). Awe is a self-transcendent emotion that occurs when one encounters perceptually extraordinary stimuli (e.g., glorious sunsets and intellectual epiphany) that transcend people’s current cognitive frame and arouse a need to update their mental schema (Keltner & Haidt, 2003; Shiota et al., 2007). Although awe feelings may sometimes be accompanied by anxiety and fear, it is generally considered a positive mixture of wonder, amazement, elevation, appreciation, and admiration (Gordon et al., 2017; Keltner & Haidt, 2003; Piff et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018, 2019).

Despite the lack of direct evidence linking dispositional awe to psychosocial flourishing, a growing body of circumstantial evidence lends support to the idea that dispositional awe makes people flourish in life (Huta & Ryan, 2010; Seaton & Beaumont, 2015). Psychosocial flourishing is considered to be parallel to eudaimonic well-being (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2016). Awe, as a type of eudaimonic emotion (Landmann, 2021), has been shown to be positively related to eudaimonic pursuits (Huta & Ryan, 2010). Individuals who experience awe generate more personal growth goals that are linked to eudaimonic well-being (Seaton & Beaumont, 2015). In addition, quite a few studies have suggested that dispositional awe can increase individuals’ hedonic well-being (Dong & Ni, 2020; Gordon et al., 2017; Rudd et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2019). Although psychosocial flourishing is somewhat different from hedonic well-being (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2016), it is generally regarded as a combination of high levels of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being (Huppert, 2009; Huppert & So, 2013; Keyes, 2002; Mesurado et al., 2021; Schueller & Seligman, 2010). In this sense, dispositional awe can promote individuals’ psychosocial flourishing.

Moreover, dispositional awe has been found to be positively correlated with several indicators that can reflect psychosocial flourishing (Danvers et al., 2016; Piff et al., 2015; Prade & Saroglou, 2016; Stellar et al., 2017; Stellar et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018, 2019). For instance, dispositional awe has been proven to encourage people to participate in various prosocial behaviors (Li et al., 2019; Perlin & Li, 2020; Piff et al., 2015; Prade & Saroglou, 2016; Rudd et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2018) and reduce aggressive behaviors (Yang et al., 2016), while engaging in more positive prosocial behaviors and fewer risky antisocial behaviors is precisely the sign of flourishing in emerging adulthood (Nelson & Padilla-Walker, 2013). Taken together, evidence is accumulating in support of the notion that dispositional awe contributes to psychosocial flourishing. Based on the above-mentioned literature, we put forward the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. Dispositional awe positively predicts psychosocial flourishing.

The Underlying Mechanisms Between Dispositional Awe and Psychosocial Flourishing

What potential mediating processes can account for the positive relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing? As a positive self-transcendental emotion, awe can not only broaden people’s understanding of life meaning, prompt them to discover and maintain a positive meaning in life, and thus expand their intrapersonal resources (Danvers et al., 2016; Landmann, 2021; Zhao et al., 2019), but also increase people’s sense of connectedness with others, and thus construct their interpersonal resources (Petersen et al., 2019; Stellar et al., 2017). Furthermore, the intrapersonal factor of meaning in life and the interpersonal factor of social connectedness have been shown to be beneficial to individuals’ well-being and positive development (Howell et al., 2013; Krok, 2018; Padilla-Walker et al., 2017). That’s to say, people’s good functioning in both intrapersonal and interpersonal aspects helps to flourish in life (Diener et al., 2010; Ng et al., 2021). As Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory suggests, the recurrent experiences of positive emotions can broaden people’s perspectives in both intrapersonal and interpersonal domains and build enduring personal resources that support human flourishing (Fredrickson et al., 2008; Garland et al., 2010). Along this line, a reasonable assumption within the framework of broaden-and-build theory is that dispositional awe—a positive emotional tendency—might enhance individuals’ psychosocial flourishing by providing abundant intrapersonal and interpersonal resources. Therefore, in this study, we attempt to identify whether meaning in life, as an intrapersonal mediator, and social connectedness, as an interpersonal mediator, would simultaneously explain why dispositional awe can promote psychosocial flourishing.

Intrapersonal Mechanism: The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life

Meaning in life refers to the belief that one’s life or existence is coherent, significant, and endowed with a supreme sense of purpose or mission (Martela & Steger, 2016; Steger, 2009). It functions as a self-regulatory and motivational intrapersonal strength for orienting people to engage in activities that help them alive and thriving (Routledge & FioRito, 2021). In the face of unfavorable life outcomes, meaning provides psychological resources for coping with these frustrations and challenges (Floyd et al., 2013; Webster & Deng, 2014). Research has found that the feeling and experience of self-transcendence can enhance people’s sense of meaning in life (Howell et al., 2013). As a self-transcendental experience (Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012), dispositional awe has been shown to be positively correlated with meaning in life (Zhao et al., 2019). In support, participants who are induced with awe in a laboratory also report a higher degree of meaning in life (Hoeldtke, 2016). The experience of awe plays a distinct role in meaning-making, it broadens people’s thinking, increases the possibility of finding new positive meanings in life (Bonner & Friedman, 2011; Krause & Hayward, 2015), encourages people to transcend mundane concerns and endorse spiritual beliefs (Jiang et al., 2018; Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012), provides them with opportunities to shape and elaborate their life frameworks, and facilitates the development of a personal sense of meaning in life (Danvers et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2019).

On the other hand, meaning in life is a well-documented factor that contributes to well-being (Aruta, 2021; Howell et al., 2013; Krok, 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Seligman, 2018; Steger et al., 2009). It is a unique psychological asset that can promote positive human functioning and nurture positive development in emerging adulthood (Steger et al., 2009). If an individual is in a meaningless state, it can lead to a situation called “existential vacuum”, which manifests as boredom, depression, or aggressive behaviors (Kleftaras & Psarra, 2012). Research on different facets of psychosocial flourishing shows that meaning in life is positively associated with psychological adjustment and prosocial behaviors (Li et al., 2019; Lin, 2021; Park & Baumeister, 2017) and serves as a buffer against poor psychological health and risk behaviors (Brassai et al., 2011; Kleftaras & Psarra, 2012). As such, it is reasonable to expect a positive association between meaning in life and psychosocial flourishing. In summary, we attempt to test the mediating effect of meaning in life as an intrapersonal factor in the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing. Dispositional awe is expected to increase one’s meaning in life, which, in turn, will contribute to the psychosocial flourishing of emerging adults. The second hypothesis is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 2. Meaning in life serves as an intrapersonal mediator in the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing.

Interpersonal Mechanism: The Mediating Role of Social Connectedness

Along with the intrapersonal force of meaning in life, the interpersonal force of one’s social connections with others also exert a great influence on emerging adults’ psychosocial flourishing (Padilla-Walker et al., 2017). Social connectedness is defined as the sense of closeness and togetherness with one’s social environment (Lee & Robbins, 1995), reflecting a holistic assessment of interpersonal relationships from a social other to a larger society (Ng et al., 2020). It is a vital psychosocial capital that can provide people with sufficient interpersonal resources to adapt to their environment and foster divergent forms of psychosocial flourishing (Eraslan-Capan, 2016; Lee et al., 2001; Saeri et al., 2018; Sedikides et al., 2016; Yıldırım et al., 2021). For instance, longitudinal studies with large representative samples have demonstrated that social connectedness predicts a greater sense of well-being (Jose et al., 2012) and lower depressive symptoms (Jose & Lim, 2014) in adolescents over time. Under stressful or threatening situations, people usually rely on social connections for protection, and those who feel socially connected experience better mental and physical health. Conversely, the deterioration or severance of valuable social connections that accompany life transitions leaves people feeling lonely and frustrated in the social world (Duru & Poyrazli, 2011; Satici et al., 2016; Wildschut et al., 2010).

While the link between social connectedness and psychosocial flourishing has been well deduced, one’s dispositional inclination to feel awe should also influence one’s social connectedness. Research has suggested that self-transcendent emotions are particularly adept at building social resources because they can bond individuals together (Stellar et al., 2017). As a self-transcendent emotion, awe has been demonstrated to generate and foster social connectedness (Perlin & Li, 2020; Shiota et al., 2007). It broadly enhances the feelings of oneness with others, not only with friends, but also with people in general (Bai et al., 2017; Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012). As Keltner and Haidt (2003) claimed, awe can unite individuals with a wide range of social entities, such as the nation or human society. Particularly, studies have revealed that experimentally manipulating feelings of awe can reduce the importance people attach to their individual selves and cultivate connection and love toward others through prosociality (Bai et al., 2017; Piff et al., 2015; Stellar et al., 2017, 2018; Zhao et al., 2018). Hence, it is logical to assume that dispositional awe is an effective strategy in bolstering social connectedness. Overall, other than intrapersonal factors, we attempt to examine the mediating effect of social connectedness as an interpersonal factor in the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing. Specifically, we propose that dispositional awe will enhance one’s social connectedness, which, in turn, will promote the psychosocial flourishing of emerging adults. The third hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 3. Social connectedness serves as an interpersonal mediator in the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing.

Intrapersonal Versus Interpersonal Pathways Among Emerging Adults

In this study, we also sought to ascertain the relative importance of the intrapersonal and interpersonal pathways underlying the effect of dispositional awe on psychosocial flourishing among emerging adults. Specifically, which psychological resources contribute more to the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing, meaning in life or social connectedness? Meaning in life reflects individuals’ view of their own life, whereas social connectedness reflects individuals’ view of social relations; both are important in their own ways for emerging adults. However, conceptually, personality traits are generally an intrapersonal factor (Ayub, 2015), and the intrapersonal nature of dispositional awe may imply that it is more relevant to the meaning in life than social connectedness. Furthermore, the exploration of life meaning signifies the internal growth of individuals and is the cornerstone of human flourishing (Routledge & FioRito, 2021). To achieve comprehensive psychosocial flourishing, social connections with others should be established to obtain external resources, and the power of these connections may be amplified by the further enrichment of life meaning. Thus, we preliminarily infer that the intrapersonal mediating mechanism of meaning in life may have a stronger effect than the interpersonal mediating mechanism of social connectedness.

Hypothesis 4. The mediation effect of meaning in life is stronger than that of social connectedness.

The Present Study

To sum up, the present study aims to investigate the effect of dispositional awe on psychosocial flourishing and test the influence of meaning in life and social connectedness in the underlying mechanism of why dispositional awe promotes psychosocial flourishing. In light of Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory, we hence build a dual-mediated model to examine: (1) whether dispositional awe positively predicts psychosocial flourishing; (2) whether meaning in life, as an intrapersonal mediator, accounts for the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing; (3) whether social connectedness, as an interpersonal mediator, accounts for the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing; and (4) the relative importance of meaning in life and social connectedness.

Method

Participants

An online survey was conducted among the emerging adulthood population in China. The survey was available through Qualtrics software (http://www.qualtrics.com), a web-based security survey data collection system. A total of 1237 emerging adults (18 to 29 years; Arnett, 2015) were randomly recruited from various industries including education, training, human services, business management, and health care in several cities in China. Each item in our survey was set as a mandatory question, and if there were missing values in the questionnaire of the participants, the system would remind them to fill in the questions again and submit the questionnaire after all questions were completed. After excluding participants with the same response across most parts of the questionnaires, one thousand two hundred and thirteen participants were included in the full analyses. There were 331 (27.3%) males and 882 (72.7%) females, with an average age of 24.09 (SD = 3.00) years. Of these participants, 116 (9.6%) had a high-school degree or below, 281 (23.2%) had a junior college degree, 728 (60.0%) held a bachelor degree, and 88 (7.3%) held a postgraduate degree.

Measures

Dispositional Awe

The 6-item dispositional awe subscale from the Dispositional Positive Emotion Scale was adopted to measure the participants’ chronic tendency to feel awe (Shiota et al., 2006). One sample item is “I often feel awe”. Participants rated items on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), and higher scores signified a higher level of dispositional awe. The Cronbach’s alpha for dispositional awe was 0.77.

Psychosocial Flourishing

The 8-item Flourishing Scale was used to access the participants’ psychosocial flourishing, describing the flourishing of human functioning (Diener et al., 2010). An example item is “I am a good person and live a good life”. Responses were indicated on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), and higher scores indicated that participants view themselves more positively in important aspects of functioning. The Cronbach’s alpha for psychosocial flourishing was 0.91.

Meaning in Life

The 10-item Meaning in Life Questionnaire was employed to capture the participants’ intrapersonal experience of meaning in life (Steger et al., 2006). The questionnaire consists of two dimensions: presence of meaning and search for meaning. All items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = absolutely untrue, 7 = absolutely true), and higher scores represented a higher level of personal meaning in life. The Cronbach’s alpha for meaning in life was 0.86.

Social Connectedness

The 20-item Social Connectedness Scale was used to access the participants’ sense of connectedness with others and the society (Lee et al., 2001). A sample item is “I feel close to people”. All items were answered on a six-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree), and higher scores reflected a stronger sense of social connectedness. The Cronbach’s alpha for social connectedness was 0.88.

Procedure

This research was approved by the ethics committee of the authors’ university. Informed consent of the participants was first obtained online, and only after the consent was given could they start to fill in the questionnaires. The participants were instructed to independently complete the above set of anonymous questionnaires, which were translated from English into Chinese and back-translated to ensure their validity for the Chinese participants. All the participants were thanked for their participation.

Data Analysis

First, we employed Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to check for the common method variance bias. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among dispositional awe, meaning in life, social connectedness, and psychosocial flourishing were then calculated using SPSS 22.0.

Next, we adopted Mplus 8.3 to run a structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the mediating effects of meaning in life and social connectedness on the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing. Following the procedure of Anderson and Gerbing (1988), a two-step approach was conducted. The measurement model was initially examined by CFA before examining the structural model. To improve the reliability of parameter estimation, three item parcels using random assignment method were created as indicators for the corresponding latent variables of dispositional awe, psychosocial flourishing and social connectedness. Moreover, the two subscale-scores of the meaning in life questionnaire (Steger et al., 2006) were used as two observed indicators for a latent variable of meaning in life. A subsequent full SEM was applied to access the hypothesized mediation model, in which mediation was specified with the direct pathway from dispositional awe to psychosocial flourishing and two indirect pathways through meaning in life and social connectedness. According to Hu and Bentler (1999), the model goodness of fit was acceptable when the RMSEA and SRMR values were lower than 0.08, and the CFI and TLI values were higher than 0.90.

Finally, Mplus’ model constraint command was conducted to examine whether one mediator had a stronger effect than the other. Specifically, the command was performed to compere the relative strength between the intrapersonal and interpersonal pathways among emerging adults.

Results

Common Method Bias Test

Harman’s one-factor test was performed to examine the common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The results of the unrotated factor analysis revealed that the first factor only explained 29.55% of the variance. Moreover, CFA demonstrated that the single-factor model fit the data poorly: χ2 (44, N = 1213) = 2385.63, χ2/df = 54.22, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.209, SRMR = 0.103, CFI = 0.72, TLI = 0.66. These results signified that the common method bias is not serious in the sample data.

Preliminary Analyses

The descriptive statistics and the correlations for the key variables were displayed in Table 1. As expected, dispositional awe was positively related to meaning in life (r = 0.47, p < 0.001), social connectedness (r = 0.32, p < 0.001), and psychosocial flourishing (r = 0.58, p < 0.001) among emerging adults, and psychosocial flourishing was positively related to meaning in life (r = 0.68, p < 0.001) and social connectedness (r = 0.59, p < 0.001). The results provided preliminary support for the hypotheses.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations for key variables

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.73 | 0.45 | – | |||||

| 2. Age | 24.09 | 3.00 | −0.16*** | – | ||||

| 3. Dispositional awe | 3.41 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.03 | – | |||

| 4. Meaning in life | 4.59 | 1.07 | 0.11*** | 0.02 | 0.47*** | – | ||

| 5. Social connectedness | 4.06 | 0.75 | 0.09** | 0.14*** | 0.32*** | 0.51*** | – | |

| 6. Psychosocial flourishing | 4.84 | 1.22 | 0.13*** | 0.08** | 0.58*** | 0.68*** | 0.59*** | – |

N = 1213. Gender: 0 = male, 1 = female; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

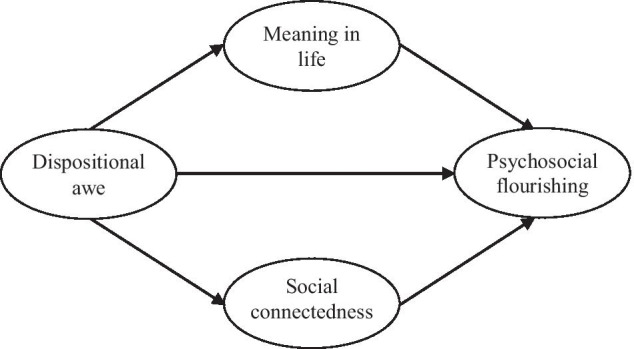

Measurement Model

The full measurement model consisted of four latent variables and eleven observed variables. The results showed a good model fit: χ2 (38, N = 1213) = 312.86, χ2/df = 8.23, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.077, SRMR = 0.043, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.95. For dispositional awe, factor loadings ranged from 0.69 to 0.80. For psychosocial flourishing, factor loadings ranged from 0.87 to 0.90. The factor loadings for meaning in life and social connectedness ranged from 0.61 to 0.67 and from 0.87 to 0.90, respectively. All the factor loadings on each latent variable were significant (p < 0.001), reflecting that the latent variables were well measured by their indicators.

Structural Model

Figure 2 shows the structural model in which we hypothesized that meaning in life and social connectedness act as mediators of the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing. The final structural mediation model evidenced a good fit to the data: χ2 (38, N = 1213) = 295.71, χ2/df = 7.78, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.075, SRMR = 0.046, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96.

Fig. 2.

The mediated structural model. ***p < 0.001; DA1-DA3 = three parcels of dispositional awe; PF1-PF3 = three parcels of psychosocial flourishing; SFM = search for meaning, POM = presence of meaning; SC1-SC3 = three parcels of social connectedness

The direct effect of dispositional awe on psychosocial flourishing in the absence of mediators was significant (β = 0.70, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.64, 0.74]). Then, tests of the indirect effects revealed that meaning in life and social connectedness mediated the relation between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing (β = 0.64, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.53, 0.85]), including specific indirect effects of meaning in life (β = 0.48, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.37, 0.69]) and social connectedness (β = 0.16, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.19]). After accounting for the mediating effects of meaning in life and social connectedness, the direct effect of dispositional awe on psychosocial flourishing become insignificant (β = 0.08, SE = 0.08, p = 0.35, 95% CI = [−0.14, 0.20]). The proportion of the total indirect effect to the total effect was 88.89%, in specific, the ratio of the mediating effects of meaning in life and social connectedness in the total effect was 66.67% and 22.22%, respectively. Taken together, these results suggested that dispositional awe exerted its effect on psychosocial flourishing through two distinct channels—the intrapersonal pathway of meaning in life and the interpersonal pathway of social connectedness. Thus, Hypothesis 1, 2 and 3 were verified.

Furthermore, the contrast test of the indirect effects showed that the difference between meaning in life and social connectedness was significant (p < 0.001), with the indirect effect of meaning in life being statistically stronger than the indirect effect of social connectedness (B = 0.67, SE = 0.17, 95% CI = [0.42, 1.10]), as demonstrated in Table 2. Therefore, the intrapersonal effect through meaning in life was more important than the interpersonal effect through social connectedness among emerging adults. Hence, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Table 2.

Standardized indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals (CI)

| Model effect | β | SE | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The total indirect effect | 0.64 | 0.08 | < 0.001 | [0.53, 0.85] |

| The indirect effect of meaning in life | 0.48 | 0.08 | < 0.001 | [0.37, 0.69] |

| The indirect effect of social connectedness | 0.16 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | [0.13, 0.16] |

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing by including meaning in life as an intrapersonal mediator and social connectedness as an interpersonal mediator. Our findings concur with Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory, suggesting that dispositional awe is positively associated with psychosocial flourishing among emerging adults, and that meaning in life and social connectedness fully mediate this positive association. In a relative sense, the mediation effect of meaning in life was stronger than that of social connectedness. These results enriched our understanding of psychosocial flourishing among emerging adults with chronic awe tendency, and identified the underlying psychological mechanisms.

Dispositional Awe and Psychosocial Flourishing

In support of Hypothesis 1, dispositional awe was found to be positively associated with psychosocial flourishing among emerging adults, which illustrated the important role of dispositional awe in promoting psychosocial flourishing. Such finding is in accordance with a laboratory research showing that when people view awe-evoking film clips, they become more motivated to pursue eudaimonic goals, thereby ultimately enhancing eudaimonic well-being (Seaton & Beaumont, 2015). Given that dispositional awe is typically characterized by positive, self-transcendent, and eudaimonic attributes (Landmann, 2021; Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012; Zhao et al., 2019), the results of this study demonstrate a positive link between dispositional awe and a more comprehensive indicator of well-being—psychosocial flourishing—that goes beyond prior research on the relationship between awe and various sub-indicators of psychosocial flourishing (Danvers et al., 2016; Piff et al., 2015; Prade & Saroglou, 2016; Stellar et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2018). This finding also deepens our understanding on the social functions of dispositional awe.

The Mediating Roles of Meaning in Life and Social Connectedness

In line with Hypotheses 2 and 3, the present study revealed that meaning in life and social connectedness jointly mediate the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing among emerging adults. In detail, dispositional awe has a significant positive effect on meaning in life and social connectedness, which, in turn, improves the level of psychosocial flourishing in emerging adults. As Fredrickson et al. (2008) stated, positive emotion builds up the necessary resources for a good life. Dispositional awe expands emerging adults’ intrapersonal and interpersonal resources that bring up-stream results to psychosocial flourishing, corresponding to the core connotation of Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson et al., 2008). The mediating roles of meaning in life and social connectedness shed light on why dispositional awe promotes psychosocial flourishing.

Findings from the mediation effect of meaning in life revealed that dispositional awe positively predicts emerging adults’ meaning in life. This finding is consistent with previous studies about individuals who experience positive awe during their daily life and a laboratory induction that reported a higher sense of life meaning (Hoeldtke, 2016; Zhao et al., 2019). Research has suggested that whether it is the positive emotion, the eudaimonic emotion, or the self-transcendental experience, they can all boost people’s sense of meaningfulness (Fredrickson et al., 2008; Howell et al., 2013; Landmann, 2021), and dispositional awe exactly coincides with these characteristics (Landmann, 2021; Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012; Zhao et al., 2019), which can broaden emerging adults’ mind and promote them to build rich intrapersonal resources. Moreover, the intrapersonal strength of meaning in life was reconfirmed to be positively correlated with psychosocial flourishing in our study, as existing research has found that meaning in life is a fundamental human need that matters for flourishing (Routledge & FioRito, 2021; Steger et al., 2009). The motivational and self-regulatory nature of meaning (Routledge & FioRito, 2021) prompt emerging adults to perform behaviors that enable them to flourish psychosocially.

Another novel observation, as predicted, was that social connectedness also mediates the positive association between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing. The result is parallel with the previous literature suggesting that experimentally induced awe engenders the feelings of social connectedness (Bai et al., 2017; Shiota et al., 2007; Van Cappellen & Saroglou, 2012). Awe experience encourages emerging adults to connect with others through expressing love and concern for others (Bai et al., 2017; Piff et al., 2015; Stellar et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018), thereby building affluent interpersonal resources (Stellar et al., 2017). In turn, the higher level of the interpersonal strength of social connectedness assists emerging adults’ psychosocial flourishing, which is in line with early studies (Jose et al., 2012; Padilla-Walker et al., 2017). Therefore, emerging adults with higher levels of dispositional awe experience a higher level of connections with others, which, in turn, further enhances their psychosocial flourishing.

Intriguingly, consistent with Hypothesis 4, from the perspective of the mediating effect, the contribution of intrapersonal pathway was more significant than that of the interpersonal pathway. Specifically, in comparison with social connectedness, meaning in life plays a relatively greater mediating role between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing. The result is similar to previous research that the effect of internal resources on psychological well-being is greater than that of external resources (Hsu & Tung, 2010). As mentioned previously, although both meaning in life and social connectedness serve as unique function that contributes to psychosocial flourishing, emerging adults’ exploration and perception of life meaning is an internal growth that can promote the vigorous development of their external social relations, which, in turn, further enhances their understandings of life meaning, forming a positive circle (Stavrova & Luhmann, 2016) conducive to the overall psychosocial flourishing. Creating and searching for a meaningful life is a prominent developmental task for emerging adults (Mayseless & Keren, 2014). Especially in the face of new situations and events, emerging adults seek to explain and reconstruct their experiences by identifying important aspects of their personal lives and discovering deeper meaning in their lives. Hence, it is reasonable to suggest that meaning in life has a stronger mediating role than social connectedness.

Limitations and Future Directions

Certain limitations should be considered in cautiously interpreting our current findings and providing guidance for further research. First, the results presented in this study cannot be regarded as a proof of causality because cross-sectional data and structural equation modeling preclude examination of causality or directionality. Future studies should adopt longitudinal data or experimental design to better verify the validity of our mediation model. Second, the participants in the present study were only emerging adults aged 18 to 29, which may be too limited in age to allow for a broader generalization. Third, our study only focused on exploring the role of dispositional awe in promoting psychosocial flourishing, but it is undeniable that there are other important factors affecting the development of individuals’ psychosocial flourishing that are not included in this study. Additional research should be conducted to explore more predictors of psychosocial flourishing in the future. Finally, this study was carried out in the collectivistic culture of China, and whether the findings are applicable to individualistic cultures remains to be further explored. Different from individualistic cultures, members of collectivist cultures tend to emphasize interdependent selves (Ng et al., 2020). As such, the effects of social relationships on them is greater than that of in individualistic culture. The current findings in collectivist culture indicate that the intrapersonal mechanism between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing is more important than interpersonal mechanism. In individualistic cultures, the difference in importance may be even greater, in which the intrapersonal mechanism between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing may be considerably much more important than interpersonal mechanism. Future research based on individualistic cultures should be conducted to confirm these conjectures.

Implications

To our knowledge, the present study is the first empirical attempt to investigate the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing in an emerging adult sample. Furthermore, this study also innovatively explored the potential mechanism of dispositional awe promoting psychosocial flourishing from the perspective of intrapersonal and interpersonal pathways. Our findings not only further enrich Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory but also contribute to the limited but growing body of research examining the social functions of dispositional awe and the protective factors of psychosocial flourishing in emerging adulthood.

Practically, our work is beneficial to the intervention aiming at promoting the positive development of emerging adults, who are in the period of transition or even lost in the transition. It is advisable for emerging adults to foster their dispositional awe through measures such as practicing loving-kindness meditation (Stell & Farsides, 2016) and improving the ability to appreciate beauty and excellence (Güsewell & Ruch, 2012), which may further enhance their meaning in life, social connectedness, and psychosocial flourishing. Moreover, the intrapersonal mechanism of meaning in life and the interpersonal mechanism of social connectedness in the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing suggests that developing intervention strategies aimed at improving emerging adults’ sense of life meaning (e.g., clarifying self-concept; Shin et al., 2016) and strengthening their social connectedness (e.g., inducing nostalgia; Sedikides et al., 2016) may also be effective ways to reduce floundering and achieve full flourishing during this vulnerable transition period. More interestingly, the comparison of the mediation effect implies that life meaning contains huge internal energy. Helping individuals in emerging adulthood find the meaning of life and gain the inner strength for growth is more conducive to them coping with various confusions and challenges in life. Meaning in life and the agency it generates has important implications for the emerging adults and even for the flourishing of society, particularly when human societies are facing existential threats, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic (Routledge & FioRito, 2021).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study elucidates the vital role of dispositional awe in promoting psychosocial flourishing in emerging adulthood and identifies an intrapersonal mechanism of meaning in life and an interpersonal mechanism of social connectedness to explain the relationship by examining a dual-process model. Furthermore, meaning in life plays a more important mediating role than social connectedness. These findings provide valuable insights into the well-being of emerging adults and identify protective factors that may contribute to their healthy transition into adulthood and psychosocial flourishing.

Author’s Contributions

Huanhuan Zhao: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Heyun Zhang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

This work was supported by the Humanity and Social Science Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (No. 19YJC190032). No competing financial interests existed.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abid G, Ijaz S, Butt T, Farooqi S, Rehmat M. Impact of perceived internal respect on flourishing: A sequential mediation of organizational identification and energy. Cogent Business & Management. 2018;5(1):1507276. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2018.1507276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):411–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The winding road from the late teens through the twenties: Emerging adulthood. Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The Oxford handbook of emerging adulthood. Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Žukauskiene R, Sugimura K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(7):569–576. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruta, J. J. B. R. (2021). The quest to mental well-being: Nature connectedness, materialism and the mediating role of meaning in life in the Philippine context. Current Psychology, 1–12. 10.1007/s12144-021-01523-y

- Ayub N. Predicting suicide ideation through intrapersonal and interpersonal factors: The interplay of Big-Five personality traits and social support. Personality and Mental Health. 2015;9(4):308–318. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Maruskin LA, Chen S, Gordon AM, Stellar JE, McNeil GD, Peng K. Awe, the diminished self, and collective engagement: Universals and cultural variations in the small self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2017;113(2):185–209. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner ET, Friedman HL. A conceptual clarification of the experience of awe: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Humanistic Psychologist. 2011;39(3):222–235. doi: 10.1080/08873267.2011.593372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brassai L, Piko BF, Steger MF. Meaning in life: Is it a protective factor for adolescents’ psychological health? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;18(1):44–51. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico A, Gaggioli A. The potential role of awe for depression: Reassembling the puzzle. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:617715. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.617715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner TS, Deyoung CG, Silvia PJ. Everyday creative activity as a path to flourishing. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2016;13(2):1–9. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1257049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danvers AF, O'Neil MJ, Shiota MN. The mind of the "happy warrior": Eudaimonia, awe, and the search for meaning in life. In: Vittersø J, editor. Handbook of eudaimonic well-being. Springer International Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente R, Parra A, Sánchez-Queija I, Lizaso I. Flourishing during emerging adulthood from a gender perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2020;21:2889–2908. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00204-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95(3):542–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi DW, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research. 2010;97(2):143–156. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong R, Ni SG. Openness to experience, extraversion, and subjective well-being among Chinese college students: The mediating role of dispositional awe. Psychological Reports. 2020;123(2):903–928. doi: 10.1177/0033294119826884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duru E, Poyrazli S. The role of demographics, English language competency, perceived discrimination and social connectedness in predicting level of adjustment difficulties among Turkish international students in the U.S. The International Journal of Psychology. 2011;46(6):446–454. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2011.585158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eraslan-Capan, B. (2016). Social connectedness and flourishing: The mediating role of hopelessness. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4(5), 933–940. 10.13189/ujer.2016.040501.

- Floyd FJ, Mailick Seltzer M, Greenberg JS, Song J. Parental bereavement during mid-to-later life: Pre-to postbereavement functioning and intrapersonal resources for coping. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28(2):402–413. doi: 10.1037/a0029986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(5):1045–1062. doi: 10.1037/a0013262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Zhang K, Chen X. Bule book of mental health: Report on national mental health development in China (2019–2020) Social Science Literature Publishing House; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Fredrickson B, Kring AM, Johnson DP, Meyer PS, Penn DL. Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(7):849–864. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AM, Stellar JE, Anderson CL, McNeil GD, Loew D, Keltner D. The dark side of the sublime: Distinguishing a threat-based variant of awe. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2017;113(2):310–328. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güsewell A, Ruch W. Are there multiple channels through which we connect with beauty and excellence? The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2012;7(6):516–529. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2012.726636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeldtke, R. T. (2016). Awesome implications: Enhancing meaning in life through awe experiences. (Doctorial dissertation), Montana State University-Bozeman, College of Letters & science.

- Howell AJ, Passmore H-A, Buro K. Meaning in nature: Meaning in life as a mediator of the relationship between nature connectedness and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2013;14(6):1681–1696. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9403-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H, Tung H. What makes you good and happy? Effects of internal and external resources to adaptation and psychological well-being for the disabled elderly in Taiwan. Aging & Mental Health. 2010;14(7):851–860. doi: 10.1080/13607861003800997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert FA. Psychological well-being: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2009;1(2):137–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01008.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert FA, So TTC. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research. 2013;110(3):837–861. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huta V, Ryan RM. Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2010;11:735–762. doi: 10.1007/s10902-009-9171-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Yin J, Mei D, Zhu H, Zhou X. Awe weakens the desire for money. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. 2018;12:e4. doi: 10.1017/prp.2017.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Lim BTL. Social connectedness predicts lower loneliness and depressive symptoms over time in adolescents. Open Journal of Depression. 2014;3(4):154–163. doi: 10.4236/ojd.2014.34019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Ryan N, Pryor J. Does social connectedness promote a greater sense of well-being in adolescence over time? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22(2):235–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00783.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D, Haidt J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion. 2003;17(2):297–314. doi: 10.1080/02699930244000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Research. 2002;43:207–222. doi: 10.2307/3090197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Dhingra SS, Simoes EJ. Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental illness. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(12):2366–2371. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2010.192245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleftaras G, Psarra E. Meaning in life, psychological well-being and depressive symptomatology: A comparative study. Psychology. 2012;3(4):337–345. doi: 10.4236/psych.2012.34048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Hayward RD. Awe of god, congregational embeddedness, and religious meaning in life. Review of Religious Research. 2015;57(2):219–238. doi: 10.1007/s13644-014-0195-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krok D. When is meaning in life most beneficial to young people? Styles of meaning in life and well-being among late adolescents. Journal of Adult Development. 2018;25(2):96–106. doi: 10.1007/s10804-017-9280-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmann, H. (2021). The bright and dark side of eudaimonic emotions: A conceptual framework. Media and Communication, 9(2), 191–201. 10.17645/mac.v9i2.3825

- LeBlanc NJ, Brown M, Henin A. Anxiety disorders in emerging adulthood. In: Bui E, Charney M, Baker A, editors. Clinical handbook of anxiety disorders. Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2020. pp. 157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Robbins SB. Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1995;42(2):232–241. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R. M., Draper, M., & Lee, S. (2001). Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: Testing a mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(3), 310–318. 10.1037//0022-0167.48.3.310.

- Li J, Dou K, Wang Y, Nie Y. Why awe promotes prosocial behaviors? The mediating effects of future time perspective and self-transcendence meaning of life. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:1140. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L. Longitudinal associations of meaning in life and psychosocial adjustment to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2021;26(2):525–534. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martela F, Steger MF. The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2016;11(5):531–545. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayseless O, Keren E. Finding a meaningful life as a developmental task in emerging adulthood: The domains of love and work across cultures. Emerging Adulthood. 2014;2(1):63–72. doi: 10.1177/2167696813515446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mesurado B, Crespo RF, Rodríguez O, Debeljuh P, Carlier SI. The development and initial validation of a multidimensional flourishing scale. Current Psychology. 2021;40:454–463. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9957-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi S, Van Quaquebeke N, Hunter JA. Flourishing and prosocial behaviors: A multilevel investigation of national corruption level as a moderator. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, Padilla-Walker LM. Flourishing and floundering in emerging adult college students. Emerging Adulthood. 2013;1(1):67–78. doi: 10.1177/2167696812470938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng JCK, Lau VCY, Chen SX. Why are dispositional enviers not satisfied with their lives? An investigation of intrapersonal and interpersonal pathways among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2020;21:525–545. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00094-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng JCK, Au AKY, Wong HSM, Sum CKM, Lau VCY. Does dispositional envy make you flourish more (or less) in life? An examination of its longitudinal impact and mediating mechanisms among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2021;22(3):1089–1117. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00265-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker, L. M., Memmott-Elison, M. K., & Nelson, L. J. (2017). Positive relationships as an indicator of flourishing during emerging adulthood. In L. M. Padilla-Walker & L. J. Nelson (Eds.), Emerging adulthood series. Flourishing in emerging adulthood: Positive development during the third decade of life (pp. 212–236). Oxford University Press.

- Park J, Baumeister RF. Meaning in life and adjustment to daily stressors. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2017;12(4):333–341. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1209542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perlin JD, Li L. Why does awe have prosocial effects? New perspectives on awe and the small self. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2020;15(2):291–308. doi: 10.1177/1745691619886006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter T, Roberts LW, Dengate J. Flourishing in life: An empirical test of the dual continua model of mental health and mental illness among Canadian university students. The International Journal Of Mental Health Promotion. 2011;13(1):13–22. doi: 10.1080/14623730.2011.9715646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen E, Fiske AP, Schubert TW. The role of social relational emotions for human-nature connectedness. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:2759. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Seligman MEP. Character strengthsand virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Piff PK, Dietze P, Feinberg M, Stancato DM, Keltner D. Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2015;108(6):883–899. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prade C, Saroglou V. Awe’s effects on generosity and helping. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2016;11(5):522–530. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1127992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge C, FioRito TA. Why meaning in life matters for societal flourishing. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;11:601899. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.601899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd M, Vohs KD, Aaker J. Awe expands people's perception of time, alters decision making, and enhances well-being. Psychological Science. 2012;23(10):1130–1136. doi: 10.1177/0956797612438731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeri AK, Cruwys T, Barlow FK, Stronge S, Sibley CG. Social connectedness improves public mental health: Investigating bidirectional relationships in the New Zealand attitudes and values survey. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2018;52(4):365–374. doi: 10.1177/00048674177239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satici SA, Uysal R, Deniz ME. Linking social connectedness to loneliness: The mediating role of subjective happiness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;97:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schotanus-Dijkstra M, Pieterse ME, Drossaert CHC, Westerhof GJ, de Graaf R, ten Have M, et al. What factors are associated with flourishing? Results from a large representative national sample. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2016;17:1351–1370. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9647-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schueller SM, Seligman ME. Pursuit of pleasure, engagement, and meaning: Relationships to subjective and objective measures of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2010;5(4):253–263. doi: 10.1080/17439761003794130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton CL, Beaumont SL. Pursuing the good life: A short-term follow-up study of the role of positive/negative emotions and ego-resilience in personal goal striving and eudaimonic well-being. Motivation and Emotion. 2015;39(5):813–826. doi: 10.1007/s11031-015-9493-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides C, Wildschut T, Cheung W-Y, Routledge C, Hepper EG, Arndt J, et al. Nostalgia fosters self-continuity: Uncovering the mechanism (social connectedness) and consequence (eudaimonic well-being) Emotion. 2016;16(4):524–539. doi: 10.1037/emo0000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Free Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2018;4(13):333–335. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1437466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JY, Steger MF, Henry KL. Self-concept clarity's role in meaning in life among American college students: A latent growth approach. Self and Identity. 2016;15(2):206–223. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2015.1111844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiota MN, Keltner D, John OP. Positive emotion dispositions differentially associated with big five personality and attachment style. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2006;1(2):61–71. doi: 10.1080/17439760500510833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiota MN, Keltner D, Mossman A. The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition and Emotion. 2007;21(5):944–963. doi: 10.1080/02699930600923668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sofija E, Harris N, Sebar B, Phung D. Who are the flourishing emerging adults on the urban east coast of Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18:1125. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrova O, Luhmann M. Social connectedness as a source and consequence of meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2016;11(5):470–479. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1117127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF. Meaning in life. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Oxford handbook of positive psychology. NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 679–687. [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(1):80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Oishi S, Kashdan TB. Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2009;4(1):43–52. doi: 10.1080/17439760802303127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stell AJ, Farsides T. Brief loving-kindness meditation reduces racial bias, mediated by positive other-regarding emotions. Motivation and Emotion. 2016;40(1):140–147. doi: 10.1007/s11031-015-9514-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stellar JE, John-Henderson N, Anderson CL, Gordon AM, McNeil GD, Keltner D. Positive affect and markers of inflammation: Discrete positive emotions predict lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. Emotion. 2015;15:129–133. doi: 10.1037/emo0000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellar JE, Gordon A, Piff PK, Anderson CL, Cordaro D, Bai Y, et al. Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: Compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Review. 2017;9(3):200–207. doi: 10.1177/1754073916684557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stellar JE, Gordon A, Anderson CL, Piff PK, McNeil GD, Keltner D. Awe and humility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2018;114(2):258–269. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang XQ, Duan WJ, Wang ZZ, Liu TY. Psychometric evaluation of the simplified Chinese version of flourishing scale. Research on Social Work Practice. 2016;26(5):591–599. doi: 10.1177/1049731514557832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cappellen P, Saroglou V. Awe activates religious and spiritual feelings and behavioral intentions. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2012;4(3):223–236. doi: 10.1037/a0025986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JD, Deng XC. Paths from trauma to intrapersonal strength: Worldview, posttraumatic growth, and wisdom. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2014;20(3):253–266. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2014.932207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Routledge C, Arndt J, Cordaro F. Nostalgia as a repository of social connectedness: The role of attachment-related avoidance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(4):573–586. doi: 10.1037/a0017597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D., Crapnell, T., Lau, L., Bennett, A., Lotstein, D., Ferris, M., & Kuo, A. (2018). Emerging adulthood as a critical stage in the life course Handbook of Life Course Health Development (pp. 123–143): Springer: Cham, Switzerland. [PubMed]

- Yang Y, Yang Z, Bao T, Liu Y, Passmore H-A. Elicited awe decreases aggression. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. 2016;10:e11. doi: 10.1017/prp.2016.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, M., Çiçek, İ., & Şanlı, M. E. (2021). Coronavirus stress and COVID-19 burnout among healthcare staffs: The mediating role of optimism and social connectedness. Current Psychology, 1–9. 10.1007/s12144-021-01781-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhao H, Zhang H, Xu Y, Lu J, He W. Relation between awe and environmentalism: The role of social dominance orientation. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:2367. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Zhang H, Xu Y, He W, Lu J. Why are people high in dispositional awe happier? The roles of meaning in life and materialism. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:1208. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.