See article vol. 29: 38-49

Osawa et al. investigated the cholesterol levels of children ages 6–7 years (first grade) to 14–15 years (ninth grade) 1) . These were the data of the same individual collected 9 years from the same area. Long-term surveys regarding lipids in children are limited; hence, this gives us meaningful information. Here I summarize the cholesterol levels in Japanese children and describe some clinical cautions for the diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia.

Tracking of Cholesterol from Childhood to Adulthood

First, Osawa et al. reported that total cholesterol (TC) level was strongly tracked from childhood to adolescence for 9 years, and the group with high TC level in childhood had high TC level also in adulthood 1) . This phenomenon is assumed to be associated with both one’s genetic factors and lifestyle. Generally, changing the food preference and exercise habits formed in early childhood is not easy. In another instance, obese children are also predisposed to obese adults. Thus, the management of lipids in childhood is key to prevent future cardiovascular disease.

From the aspect of atherosclerosis, measuring LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) or non-HDL cholesterol (non-HDL-C) is better instead of TC, because approximately 10% of children have more than 80 mg/dL of HDL-C 2) . Non-HDL-C is strongly correlated with LDL-C and is almost LDL-C plus 10–15 mg/dL in children. Additionally, there are two important points to analyze lipid data in children; one is whether overweight/obese children are accurately evaluated 3) and how to handle their data; and the other is the presence of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). Obese children tend to have high LDL-C same as adults, and FH children of course have remarkable hyper LDL cholesterolemia.

Physiological Changes in Cholesterol Levels in Children

Second, Osawa et al. showed the changes in TC levels with age in boys and girls 1) . It is necessary to make the variation pattern clear. They reported that the mean TC level was the highest in the fifth grade (10–11 years) and that it descended up to the ninth grade (14–15 years) for boys. For girls, TC level started to decline from the fifth grade and started to rise from the seventh grade (12–13 years); see their Fig.1A and 1B 1) .

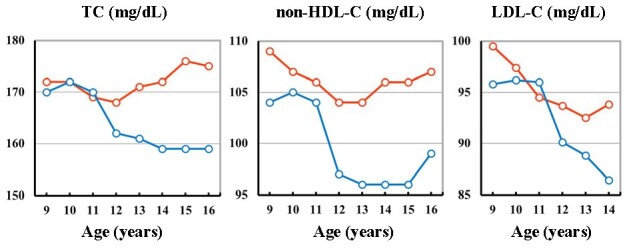

Previously, Okada et al. 2) in the 1990s and Abe et al. 4) in the 2000s conducted a nationwide children’s lipid survey in Japan. The 2000s data are not significantly different from 1990s data. Fig.1 shows the changes in TC, non-HDL-C, and LDL-C with aging, which are made by their data 2 , 4) . Abe et al. reported that TC and non-HDL-C in boys started to decline from 11 years of age and those in girls started to rise from 12 years of age 4) . Their TC graph shows completely the same pattern as Osawa’s graph. Physiological changes in cholesterol show a certain degree of sex difference. Okada et al. calculated LDL-C by Friedewald equation 2) . The LDL-C shows a continuous decrease from 11 to 14 years of age for boys and from 9 to 13 years of age for girls. This decrease in LDL-C must be the pubertal change, considering that boys enter puberty from around 11 years old and girls from around 10 years old in Japan.

Fig.1. Changes in Japanese TC, non-HDL-C, and LDL-C levels during school-age.

The 50th percentile values of TC, non-HDL-C, and LDL-C at each age were plotted in Japanese boys (blue line) and girls (red line). Data were from a nationwide survey by Abe et al. 4) for TC and non-HDL-C and data by Okada et al. 2) for LDL-C.

Eissa et al. reported that TC, LDL-C, and non-HDL-C levels decreased throughout puberty, but not HDL-C nor TG 5) . The LDL-C levels declined in successive pubertal stages between pubertal stage 2 and stage 4 5 , 6) . At each pubertal stage, mean LDL-C for females was significantly higher (by about 4 mg/dL) than that for males, in both black and nonblack. The mean LDL-C value at stage 5 (completed stage) was about 9 mg/dL lower than that at stage 1 (pre-pubertal stage). The difference is small, but there could be a wide individual variation in each stage, but the details were not described. The peak of the prevalence of obesity is 11–12 years old in both Japanese school-age boys and girls 7) . Thus, the decrease of LDL-C during puberty may be offset by the increase of LDL-C induced by obesity to some extent.

The question arises why serum LDL-C is continuously decreased during puberty. To my knowledge, the precise mechanism of the decrease has not been elucidated. Serum testosterone and estradiol are increased from about 10 years old, and then, both hormones reached the adult level at about 15 years old in both boys and girls. Their direct effects on LDL metabolism in puberty is unclear. Japan’s Education at a Glance 2006 shows the age of highest growth for boys is 11 years, whereas for girls the age is 9 years. The age for boys during which they gain weight the greatest is 11 years, whereas for girls, the age is 10 years 7) . At this time, the answer to the question is believed to be due to the increase of requirement of cholesterol for the rapid cell growth, and LDL fraction is mainly used in serum lipids.

Individual variation in the onset or progression of puberty also exists. When we diagnose or give some treatments to a child with hypercholesterolemia such as FH, we should check and consider his or her pubertal stage carefully 8) .

LDL-C level from children to young adults and diagnosis of FH

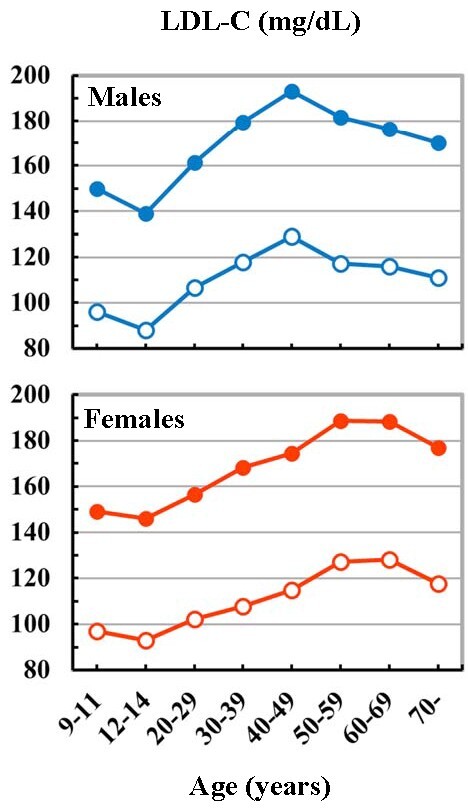

On the basis of Okada’s data 2) and Japanese national data 2018 9) , Fig.2 shows the Japanese LDL-C levels from childhood to adulthood. The mean LDL-C levels are dramatically increased after puberty. Once the LDL production is activated or the LDL degradation system is inactivated during puberty because of an increase in its consumption, the program may not be regulated soon after puberty. The peak LDL-C was in the 40s in males and in the 50s–60s in females. LDL-C levels of Japanese adults are not significantly changed at least in the recent 10 years.

Fig.2. Japanese LDL-C levels with age.

The graphs are two combined data. The children’s data are from the survey by Okada et al. 2) , and the adult’s data are from the National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan, 2018 (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan) 9) .

Blue lines: boys and males. Red lines: girls and females. Closed circles: the 97th percentile values (<15 years) and mean+2SD (97.7th percentile) values (≥ 20 years). Open circles: the 50th percentile values.

It is important to know not only the mean value but also the upper normal limit of LDL-C at each age, especially when FH patients are diagnosed. Fig.2 also shows the upper values of LDL-C. The 97th percentile values range 140–150 mg/dL in children. After puberty serum LDL-C is rapidly increased to 160 mg/dL in the 20s, then 180 mg/dL in the 30s in males, and the 40s in females (mean+2 standard deviation value equals to the 97.7th percentile value).

LDL-C of ≥ 140 mg/dL for children (<15 years) 10) or ≥ 180 mg/dL for adults (≥ 15 years) 11) is a key diagnostic criterion for FH in Japan. When a child is diagnosed with FH and when the statin treatment is started, we should measure serum LDL-C several times and also check the puberty stage. The Tanner method is the most useful tool to see the pubertal stage in clinic 6) . As stated above, LDL-C is decreased during puberty, so one’s puberty stage may predict the next serum LDL-C change. For young adults, the current criterion for FH, LDL-C of ≥ 180 mg/dL, seems to be too high. If a man or woman before 30 years of age has family history of FH, LDL-C of ≥ 160 mg/dL is the strongly suspected FH.

Conflicts of Interest

I have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1).Osawa E, Asakura K, Okamura T, Suzuki K, Fujiwara T, Maejima F, Nishiwaki Y. Tracking Pattern of Total Cholesterol Levels from Childhood to Adolescence in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2022; 29: 38-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Okada T, Murata M, Yamauchi K, Harada K. New criteria of normal serum lipid levels in Japanese children: the nationwide study. Pediatr Int, 2002; 44: 596-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Dobashi K. Evaluation of Obesity in School-Age Children. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2016; 23: 32-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Abe Y, Okada T, Sugiura R, Yamauchi K, Murata M. Reference Ranges for the Non-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Japanese Children and Adolescents. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2015; 22: 669-675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Eissa MA, Mihalopoulos NL, Holubkov R, Dai S, Labarthe DR. Changes in Fasting Lipids during Puberty. J Pediatr, 2016; 170: 199-205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Tanner JM. Growth of Adolescents. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1962 [Google Scholar]

- 7).Japan’s Education at a Glance 2006, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan: https://www.mext.go.jp/en/publication/statistics/title04/detail04/1373658.htm [Google Scholar]

- 8).Yamashita S, Masuda D, Akishita M, Arai H, Asada Y, Dobashi K, Egashira K, Harada-Shiba M, Hirata K, Ishibashi S, Kajinami K, Kinoshita M, Kozaki K, Kuzuya M, Ogura M, Okamura T, Sato K, Shimano H, Tsukamoto K, Yokode M, Yokote K, Yoshida M. Guidelines on the Clinical Evaluation of Medicinal Products for Treatment of Dyslipidemia. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2020; 27: 1246-1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan, 2018, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000681200.pdf (Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 10).Harada-Shiba M, Ohta T, Ohtake A, Ogura M, Dobashi K, Nohara A, Yamashita S, Yokote K. Joint Working Group by Japan Pediatric Society and Japan Atherosclerosis Society for Making Guidance of Pediatric Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Guidance for Pediatric Familial Hypercholesterolemia 2017. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2018; 25: 539-553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Harada-Shiba M, Arai H, Ishigaki Y, Ishibashi S, Okamura T, Ogura M, Dobashi K, Nohara A, Bujo H, Miyauchi K, Yamashita S, Yokote K. Working Group by Japan Atherosclerosis Society for Making Guidance of Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Familial Hypercholesterolemia 2017. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2018; 25: 751-770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]