Abstract

Metastases account for the majority of mortalities related to breast cancer. The onset and sustained presence of hypoxia strongly correlates with increased incidence of metastasis and unfavorable prognosis in breast cancer patients. The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway is dysregulated in breast cancer, and its abnormal activity enables tumor progression and metastasis. In addition to programming tumor cell behavior, Hh activity enables tumor cells to craft a metastasis-conducive microenvironment. Hypoxia is a prominent feature of growing tumors that impacts multiple signaling circuits that converge upon malignant progression. We investigated the role of Hh activity in crafting a hypoxic environment of breast cancer. We used radioactive tracer [18F]-fluoromisonidazole (FMISO) positron emission tomography (PET) to image tumor hypoxia. We show that tumors competent for Hh activity are able to establish a hypoxic milieu; pharmacological inhibition of Hh signaling in a syngeneic mammary tumor model mitigates tumor hypoxia. Furthermore, in hypoxia, Hh activity is robustly activated in tumor cells and institutes increased HIF signaling in a VHL-dependent manner. The findings establish a novel perspective on Hh activity in crafting a hypoxic tumor landscape and molecularly navigating the tumor cells to adapt to hypoxic conditions. Importantly, we present a translational strategy of utilizing longitudinal hypoxia imaging to measure the efficacy of Vismodegib in a preclinical model of triple-negative breast cancer.

Keywords: Hypoxia, Hedgehog pathway, Breast Cancer, Metastasis, FMISO

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most commonly occurring cancers in women worldwide. Hypoxic conditions within breast tumors have been identified as an adverse indicator for patient prognosis (1). Hypoxia is created by the rapid increase in cellular density and concomitantly decreased apoptosis. The need for higher oxygen consumption paired with remoteness from the nearest blood vessel reduces oxygen availability within the tumor and consequently drives hypoxia. Hypoxia leads to the formation of structurally and functionally abnormal blood vasculature within the solid tumor, aiding in tumor progression (2). From an extensive study, it has been shown that the mean partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) in breast tumors ranges from 2.5 to 28 mm of mercury (Hg), with a median value of 10 mm Hg, as compared with 65 mm Hg in normal human breast tissue (3). Intratumoral hypoxia profoundly modulates gene expression and cellular communication and also reconfigures the tumor microenvironment (structurally and compositionally); therefore, it is critical to decipher the mechanisms underlying the development of a hypoxic environment and the cellular adaptation of cancer cells to hypoxia.

The transcription factor HIF-1α is the main driver of hypoxia. HIF-1α dimerizes with HIF-1β and transactivates numerous genes through binding to hypoxia response elements (HREs) in promoters or enhancers, leading to activated expression of several genes that impinge upon angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, survival, and metastatic dissemination (3,4). HIF-1α transcription factor is regulated in an oxygen-dependent manner through prolyl hydroxylation by proline hydroxylase (PHD), ubiquitination by an E3 ligase called Von Hippel Lindau protein (VHL), and proteasomal degradation by the 26S proteasome (5). Recent studies have shown that growth factor signaling pathways like phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), mouse double minute 2 homolog (Mdm2), and heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) can activate the HIF-1α mediated hypoxic response (6).

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway is aberrantly activated in breast cancer (7). We and others have reported that dysregulated Hh activation enables and enhances tumor malignancy and metastatic potential (8–10). Hh signaling is much appreciated for its indispensable involvement in stem cell maintenance, development, patterning and differentiation, and epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) (7). Signaling via the mammalian Hh signaling pathway is initiated by one of the activating ligands, Indian hedgehog (IHH), Desert hedgehog (DHH), or Sonic hedgehog (SHH). Once ligand binding occurs, the inhibitory action of the 12-pass transmembrane protein receptor, Patched1 (PTCH1) is disengaged; this enables Smoothened (SMO), a 7-pass transmembrane G-protein coupled signal transduction molecule to activate a series of events. As a consequence, the glioma associated oncogene homolog (GLI) transcription factors translocate to the nucleus. There are three GLI transcription factors – while GLI1 functions primarily as a transcription activator, the functions of GLI2 and GLI3 can be more context-dependent (7). However, apart from the classical pathway, cytokines from the tumor microenvironment (TME) can also elicit GLI protein activity independent of Hh ligands; these include TGFβ, OPN, and EGF (11). As such, the TME significantly influences the behavior of cancer cells and ultimately their response to therapy. Recent studies have implicated a possible role of Hh signaling in the hypoxic TME (12–15). However, the functional and mechanistic role of the Hh pathway in crafting a hypoxic tumor niche and influencing cancer cell adaptation to the hypoxic microenvironment remains unexplored.

Molecular imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) provides a noninvasive and translational approach to probing biological mechanisms in oncology that encompass information from the entire three-dimensional tumor. [18F]-FMISO-PET imaging is widely used to detect intracellular hypoxia within the tumor in breast cancer patients and in preclinical models of breast cancer (16–18). [18F]-FMISO is a radiotracer that non-invasively diffuses into cells under normal oxygen concentration. However, under hypoxic conditions, the nitroimidazole group of [18F]-FMISO is reduced and retained in PO2 less than or equal to 10mm Hg. [18F]-FMISO covalently binds to cellular molecules at rates that are inversely proportional to oxygen concentration. [18F]-FMISO has a half-life of 110 minutes and clearance of the tracer is seen in the liver, kidney, and bladder (19). [18F]-FMISO-PET imaging has been assessed as a predictive prognostic factor in patients with pancreatic and breast cancer (16,20). [18F]-FMISO retention at higher rates has been correlated with shorter progression-free survival in renal and head-and-neck cancer (21).

We used a preclinical, syngeneic mammary tumor model to investigate the role of Hh signaling in sculpting tumor hypoxia. We quantified changes in hypoxia using [18F]-FMISO-PET imaging and also undertook mechanistic investigations to unravel the role of Hh activity in programming tumor cells to adapt to hypoxia. Our findings provide novel insight into the role of Hh pathway as a modifier of temporal changes in tumor hypoxia. We also show that hypoxia exacerbates Hh/GLI transcriptional activity that in turn, enables robust HIF-signaling. Our findings implicate that Hh signaling-associated hypoxia adaptation presents as a targetable vulnerability of breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

SUM1315 and SUM159 breast cancer cells acquired from Asterand, Inc were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher), 5 mg/ml insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and either 10 ng/ml EGF (Sigma-Aldrich) or 1μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich), respectively, without antibiotics or antimycotics (15). MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 5% FBS. MDA-MB-436 and MDA-MB-468 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS. 4T1 cells were cultured in RPMI with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. All cells were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 environment. Cell lines are typically used in their early passages. We expand cells at low passages and freeze multiple stocks. After about 10–15 passages, a new vial is thawed. All cell lines used are routinely tested for Mycoplasma. We have authenticated our 4T1 cells with services from ATCC.

For hypoxic culture conditions, cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified hypoxic chamber (Billups Rothenberg Inc., Del Mar, CA) infused with 1% O2, 5% CO2 and 94% N2. Cells were incubated for 24hrs unless mentioned otherwise.

Hedgehog Pathway Inhibition

Breast cancer cells were treated with various inhibitors. Unless otherwise mentioned, cells were pretreated for 24 hours with the inhibitors, followed by other treatments. The inhibitors include GANT61 (Tocris, Avonmouth, Bristol, UK), BMS-833923 (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX), and Vismodegib (Selleck Chemicals).

SUM1315, SUM159, and 4T1 were stably transfected with non-targeting plasmid control (NT) or GLI1 shRNA (shGLI1) and selected on G418 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as previously described (22).

Western Blotting Analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared by lysing cells with 2X Laemmli buffer with β-mercaptoethanol, followed by boiling at 95°C for 5 minutes. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies VHL (68547, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) or HIF-1α (human: 610959, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA; mouse: 400080, Calbiochem). Immunoblotting with β-actin (A3854, Sigma-Aldrich) or α-tubulin (12351S, Cell Signaling) were used to confirm equal loading for whole cell lysates. Anti-rabbit or anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) were used for detection, and blots were developed with either ECL or Super Signal substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and imaged using an Amersham Imager 600.

Luciferase Assays

Cells were seeded at 25,000 cells per well of a 96-well plate and the following day transiently transfected with 50ng/well of HRE-luc or 8X-GLI-luc reporter DNA using Fugene6 (Promega, Madison, WI). Twenty-four hours later, the transfection mix was removed and replaced with regular growth media. Where applicable, the cells were placed in hypoxic conditions in media containing inhibitor for an additional 24 hours. The data represented is the relative light units (RLU) normalized to total protein, performed in triplicate.

Drug/Inhibitor Treatments

Twenty-four hours after seeding, cells were treated with 150 μM VH298 (Sigma-Aldrich) or 10μM clasto-Lactacystin β-Lactone (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hours. The media was replaced with media without inhibitors and put in hypoxia chamber for 24 hours. Lysates were collected with 2X Laemmli buffer.

Transfection

VHL was silenced using ON-TARGET plus Human VHL or non-Target control siRNA (Dharmacon). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturers’ protocol. 24 hours after transfection cells were treated with either BMS 2.5μM (Selleck chemicals) or DMSO for 24 hours and then fresh media with inhibitor were added and cells were incubated in either normoxia or hypoxia for 24 hours. Lysates were collected with 2X Laemmli buffer.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA was collected from SUM1315 and SUM159 cells using Qiagen RNAeasy Mini Kit (Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized using High Capacity Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Thermo Fisher), and qRT-PCR was performed using StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan Fast Advanced Master mix (Applied Biosystems) was used for gene expression assays. TaqMan primers (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) used were GLI1 (Hs01110766_m1), GLI2 (Hs00257977_m1), PTCH1 (Hs00181117_m1), VHL (Hs03046964_s1), CAIX (Hs00154208_m1), and ACTB (Hs99999903_m1). Steady-state transcript levels were calculated using the change in the CT method and normalized to β-actin as previously described (23).

Inhibition/Stimulation of Hh signaling in 4T1 cells

4T1 cells were plated in 60mm dishes and the following day, treated with DMSO, 100nM recombinant mouse SHH (R&D Systems) or 10uM GANT61 (Sigma). 24 hours later, RNA from cells was harvested using Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit according to manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit under the following protocol: 25°C for 10 minutes, 37°C for 120 minutes, 85°C for 5 minutes. Real time PCR was performed using TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and Taqman gene expression assay probes for Gli1 (Mm00494654_m), Gli2 (Mm01293111_m1), Ptch1 (Mm00436026_m1), Vegfa (Mm01281449_m1), Actb (Mm02619580_m1) (Thermo Fisher). Actb served as an endorse control gene. Each reaction was done in triplicate using an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus Real Time PCR system.

Immunocytochemistry

SUM1315 cells grown on coverslips and incubated in normoxia or hypoxia were washed in PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, then permeabilized in 1X PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were blocked in 1X PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% BSA, then incubated overnight in anti-GLI1 (2643, Cell Signaling) in 1X PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% BSA. Secondary antibody used was goat anti-Mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (A-11001, Thermo Fisher). Coverslips were mounted with VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

In vivo [18F]-FMISO-PET Imaging and Analysis

All animal studies were conducted under an IACUC-approved protocol. Eight-week-old female Balb/c mice were injected with 4T1 luciferase-expressing cells into the third mammary fat pad at a concentration of 500,000/100uL in HBSS buffer. Tumor growth was documented weekly by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) using the IVIS Lumina III imaging system (Xenogen Corp., Alameda, CA) and thrice weekly by caliper measurement. The mice were randomized based on the BLI average radiance when the average tumor diameter reached approximately 3mm (12 days post injection). Mice were orally administered 100uL of Vismodegib or DMSO vehicle control (2mg/mouse) thrice weekly following randomization for a total of 7 doses. Mice were imaged with [18F]-FMISO-PET at baseline (day 13 post injection) and on days 20 and 27. [18F]-FMISO was produced by The University of Alabama at Birmingham cyclotron facility on a GE FASTlab2 or Synthra RNplus synthesizer. Approximately 150 μCi (149.6 ± 7.9 μCi) of [18F]-FMISO was retro-orbitally injected per mouse, and 80 minutes later, mice were imaged with a Sofie GNEXT PET/CT scanner (Sofie Biosciences, Culver City, CA) for a total of 20 min for PET, followed immediately with a computed tomography (CT) for anatomical reference. Images were analyzed with VivoQuant image analysis software (InviCRO, Boston, MA). Three-dimensional regions of interest (ROIs) of tumor and normal contralateral muscle were drawn on CT and transferred to PET images to quantify mean tumor and muscle standard uptake value (SUVmean). SUV = [(MBq/mL) × (animal wt. (g))/injected dose (MBq)]. Tumor-to-muscle ratio was obtained for each mouse. SUVmean of tumors at baseline and post-Vismodegib treatment were compared to the vehicle control.

Immunohistochemistry

Primary tumors were collected for immunohistochemical processing. Paraffin-embedded slides were cut into 5μm sections and stained with CAIX (Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO) at 1:400 dilution overnight. Tumor sections were also stained with isolectin B4 (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) using the Vectastain Elite ABC-HRP kit (Vector Laboratories). Briefly, after deparaffinization and rehydration, citrate antigen retrieval and peroxidase blocking were performed. Samples were incubated overnight in primary antibody in binding buffer (10mM HEPES, 250mM NaCl, 0.1mM Ca+, 0.1% BSA), then washed with PBS + 0.05% Tween-20. Samples were incubated in ABC reagent, washed, and developed with DAB solution before being counterstained with Harris hematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted. Isolectin B4-stained slides were used to evaluate micro-vessel density by quantitating total micro-vessels per field.

Collagen fibers in the tumor tissue were visualized with picrosirius red (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA). Brightfield images were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse E200 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Polarized light images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U. Collagen content was measured using Image J by converting collagen staining to mean gray intensity.

To visualize infiltrating macrophages, the tumor sections (5μm) were immunohistochemically stained with CD206 (1:1000 dilution, Abcam Cambridge MA) or CD80 (1:500 dilution, Abcam Cambridge MA) /CD68 (1:50 dilution, Santa Cruz, Dallax, TX) dual probing (ADI-950-100, Enzo Life Science, Farmingdale, NY) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Four images per tumor were acquired using the 20X lens of Nikon A1R HD Confocal Microscope (Nikon). Images were evaluated using Fiji Image-J software.

Immunofluorescence

4T1 cell tumors from mice treated with either DMSO control or Vismodegib were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded, then sectioned at 5μm. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, and then subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval and blocked in normal donkey serum. Sections were incubated overnight in primary antibody (anti-Patched 1, Novus Biologicals 1:60, Centennial, CO) diluted in 1x PBS containing 5% BSA (BS). After washing with 1x PBS, sections were incubated in secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat, Invitrogen) diluted in BS. After washing, the TrueVIEW Autofluorescence Quenching Kit with DAPI (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to quench autofluorescence. Sections were mounted using the mounting media contained in the autofluorescence quenching kit. Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U microscope and NIS Elements software. The percent Patched 1-positive tumor cells was determined by dividing the number of Patched 1+ tumor cells by the total number of tumor cells in a field.

Ex vivo lung imaging

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with D-luciferin at 150 mg/kg. 10 minutes later, mice were put under anesthesia using isoflurane gas and euthanized. Immediately after necropsy, lungs were individually resected and placed into black paper tray. Three drops of luciferin at 150 mg/kg were added and lungs imaged at 5 mins and 3 mins, 10 bin, level B using the IVIS Lumina.

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining

Mouse tumors and tissues were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5μm) from paraffin-embedded tissue were deparaffinized and rehydrated through passages in xylene and gradients of ethanol. Slides were then immersed in Harris Hematoxylin (diluted 1:4 in tap water) for 2 minutes, de-stained by dipping in acid fast ethanol for 10 times, rinsed with tap water, immersed in Eosin Y (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) for 3 minutes, and rinsed again with tap water. Tissues were dehydrated and the slides were mounted in Cytoseal with coverslips. Images were captured using a Nikon A1R HD Microscope (Nikon) using 10X & 40X lens under bright field light. Areas of metastatic tumor foci in the lungs were analyzed using NIS-Elements AR 5.20.02 software.

Assays for glucose consumption and lactate production

Conditioned medium from cells cultured in normoxic or hypoxic conditions was collected, cleared by centrifugation, and assayed for glucose and lactate levels using the Amplex Red Glucose/Glucose Oxidase Assay Kit (Invitrogen) and Lactate Colorimetric/Fluorometric Assay Kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA), respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using multiple comparison tests per experimental design. The graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism 8 software (La Jolla, CA) and are representative of three independent replicates. Statistical significance was determined if the analysis reached 95% confidence and for p<0.05. The statistical tests used are listed in the corresponding figure legends. When appropriate, error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Results

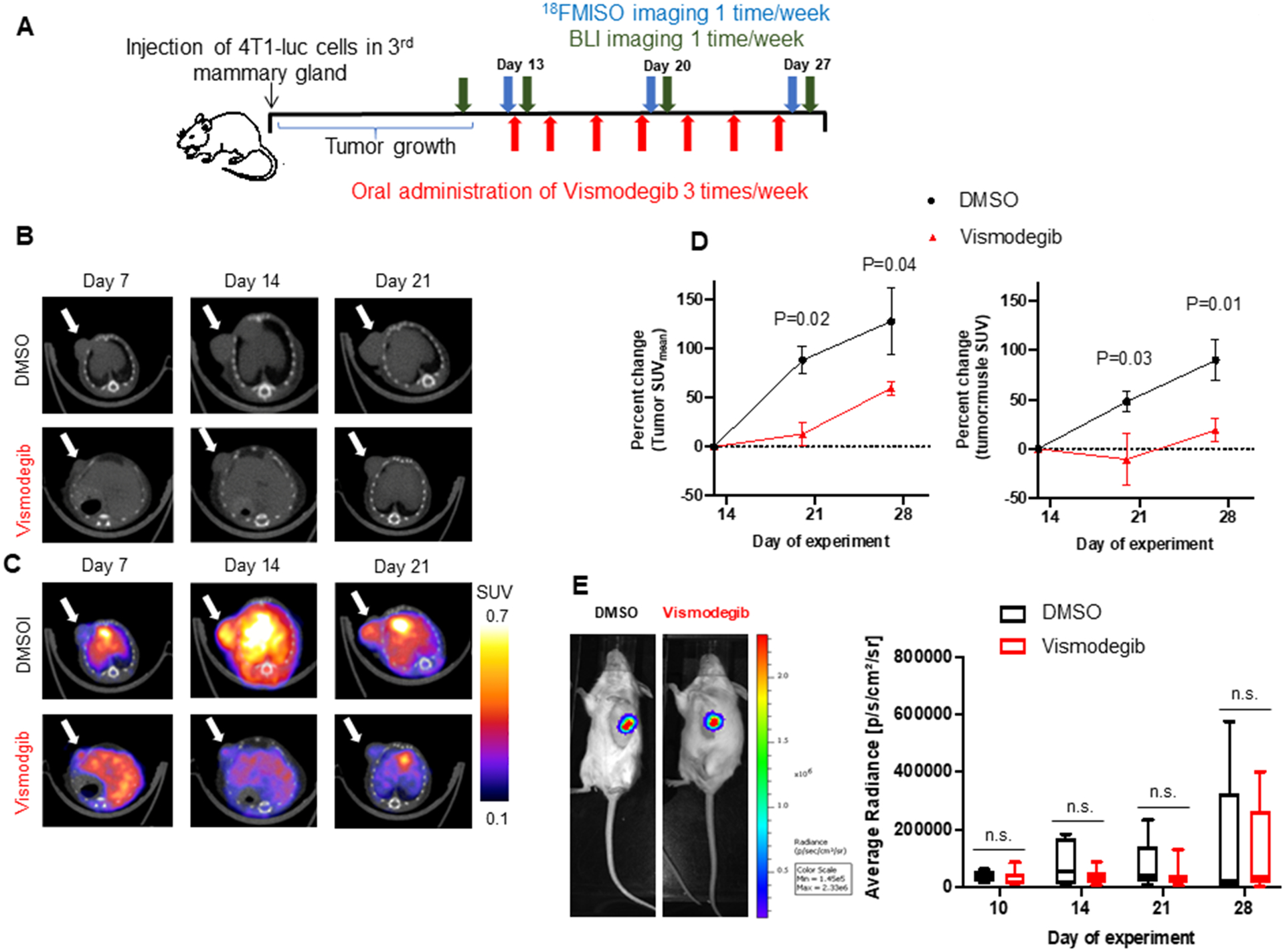

Vismodegib decreases tumor hypoxia in the 4T1-Balb/c preclinical model

To test the hypothesis that Hh activity influences the hypoxic TME, we adopted [18F]-FMISO-PET imaging. [18F]-FMISO-PET imaging is a quantitative tool that can be used to evaluate temporal changes in hypoxia (24). We conducted a longitudinal study in a 4T1 syngeneic mouse triple-negative mammary tumor model that mimics invasive and metastatic triple negative breast cancer in mice (25) and administered Vismodegib, an FDA-approved, orally available, Hh pathway inhibitor. Female Balb/c mice bearing orthotopic mammary 4T1 tumors were randomized into Vismodegib and control groups when the tumor diameter averaged ~3–4mm. Mice were orally administered either Vismodegib or vehicle control thrice weekly for 2 weeks. [18F]-FMISO-PET imaging on day 13 was used as a baseline before administration of Vismodegib. [18F]-FMISO-PET imaging after one and two weeks of DMSO or Vismodegib administration was evaluated on days 20 and 27 respectively (Figure 1A). At baseline, both groups started out with comparable average tumor size and tumor hypoxia (as determined by average tumor radiance and tumor standard uptake value (SUV), respectively). [18F]-FMISO retention longitudinally increased in tumors of mice from the control group, while in the Vismodegib-treated mice, FMISO uptake remained steady (Figure 1B, 1C). On day 20 and day 27, relative to mice administered vehicle control, hypoxia within the tumor is significantly reduced in the Vismodegib-treated group as evident by lower values of tumor SUVmean and tumor to muscle SUV ratio (Figure 1D, Supplementary Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 1B). Primary tumor growth was comparable in Vismodegib and vehicle control-treated mice as indicated by the BLI readings of the tumor, caliper measurements, and tumor weight (Figure 1E, Supplementary Figure 1C, and Supplementary Figure 1D). Collectively, these findings suggest that Hh inhibition with Vismodegib reduces the longitudinal progression of tumor hypoxia in vivo.

Figure 1. Inhibiting Hh signaling by Vismodegib mitigates tumor hypoxia.

(A) Mice experiment schema of tumor implantation, [18F]-FMISO-PET and BLI imaging, and Vismodegib administration schedule until Day 28. (B) Representative anatomical CT images of the transverse cross section of a treated and control 4T1 syngeneic mouse model through time. White arrow is pointing to the tumor. (C) Corresponding molecular FMISO-PET images overlaid on the CT anatomical images of the transverse cross section of a treated and control mice through time. Quantitative analysis with the standardized uptake value (SUV) of FMISO uptake is shown with color scale. (D) Tumor hypoxia, as quantitated by percent change in SUVmean and tumor to muscle ratio shows significantly lower [18F]-FMISO uptake in second and third week after Vismodegib treatment compared to DMSO control (n = 6). Statistical significance was determined with a one-way ANOVA sidak’s multiple comparison test. For one-way ANOVA, comparisons between DMSO and Vismodegib-treated mice are shown. All error bars depict the SEM. (E) Representative images of tumor BLI on Day 28. Average tumor size between the groups is not significantly different as imaged by the BLI.

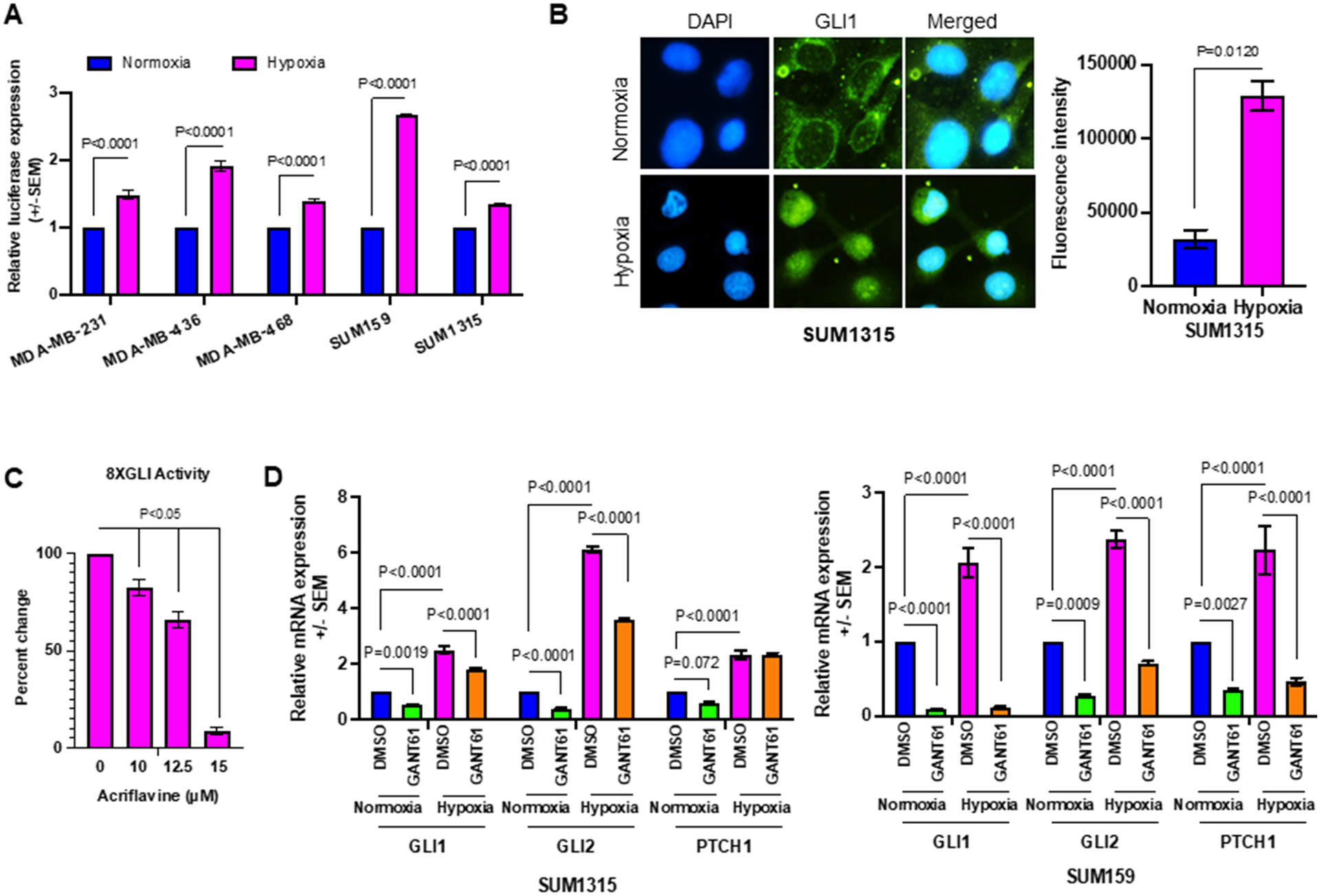

Hypoxia activates Hh signaling in tumor cells

Building upon the leads presented thus far, we sought to evaluate the relevance of Hh activity in enabling adaptation to hypoxia. We first scored the effect of hypoxia on Hh transcriptional activity. We transiently transfected MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-468, SUM159, and SUM1315 cell lines with an 8X-GLI reporter construct and incubated the cells in hypoxia for 24 hrs. We see that hypoxia supports a significant increase in 8X-GLI reporter activity relative to cells in normoxia (Figure 2A). In agreement with this, GLI1, the terminal effector protein of the Hh pathway, demonstrates nuclear accumulation in hypoxic conditions (Figure 2B). In order to query the direct effect of HIF-1α in navigating this increase in Hh activity, we treated SUM1315 cells (which support a high basal Hh activity) with acriflavine, which prevents dimerization of HIF-1α. Acriflavine caused a significant decrease in 8X GLI activity in hypoxic conditions suggesting that HIF-mediated signaling impacts Hh activation (Figure 2C). Concordant with these observations, we see that transcript levels of bonafide Hh pathway target genes GLI1, GLI2, and PTCH1 are upregulated in hypoxia. To appreciate the relevance of hypoxia-induced elevated Hh activity, we treated cells with GANT61, a direct inhibitor of GLI1/2. GANT61 antagonized hypoxia-induced upregulation of steady state transcript levels of GLI1, GLI2, and PTCH1 (Figure 2D) underscoring the role of hypoxia in elevating Hh activity. Taken together, the data suggest that hypoxia exacerbates Hh signaling in TNBC cells.

Figure 2. Hypoxia upregulates Hh activity in tumor cells.

(A) 8X-GLI-luciferase reporter assay was used to measure Hh pathway activation in normoxia versus hypoxia in MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-468, SUM159, and SUM1315 cell lines. (B) Hypoxia induces nuclear accumulation of GLI1 (24hrs in hypoxia). GLI1 was visualized by fluorescent immunocytochemistry. The graph represent the quantitation of fluorescence intensity from 20 fields at 40X magnification. (C) Acriflavine decreases 8XGLI reporter activity, in a dose-dependent manner, in SUM1315 cells. Statistical significance was determined with a one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test; comparison between control and acriflavine treated groups are shown. (D) The steady state transcript levels of bonafide Hh pathway target genes GLI1, GLI2, and PTCH1 are upregulated in hypoxia compared to normoxia in SUM1315 and SUM159 cells. Statistical significance was determined with a two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, p<0.001 for Hh target genes between normoxic and hypoxic conditions. All error bars depict the SEM.

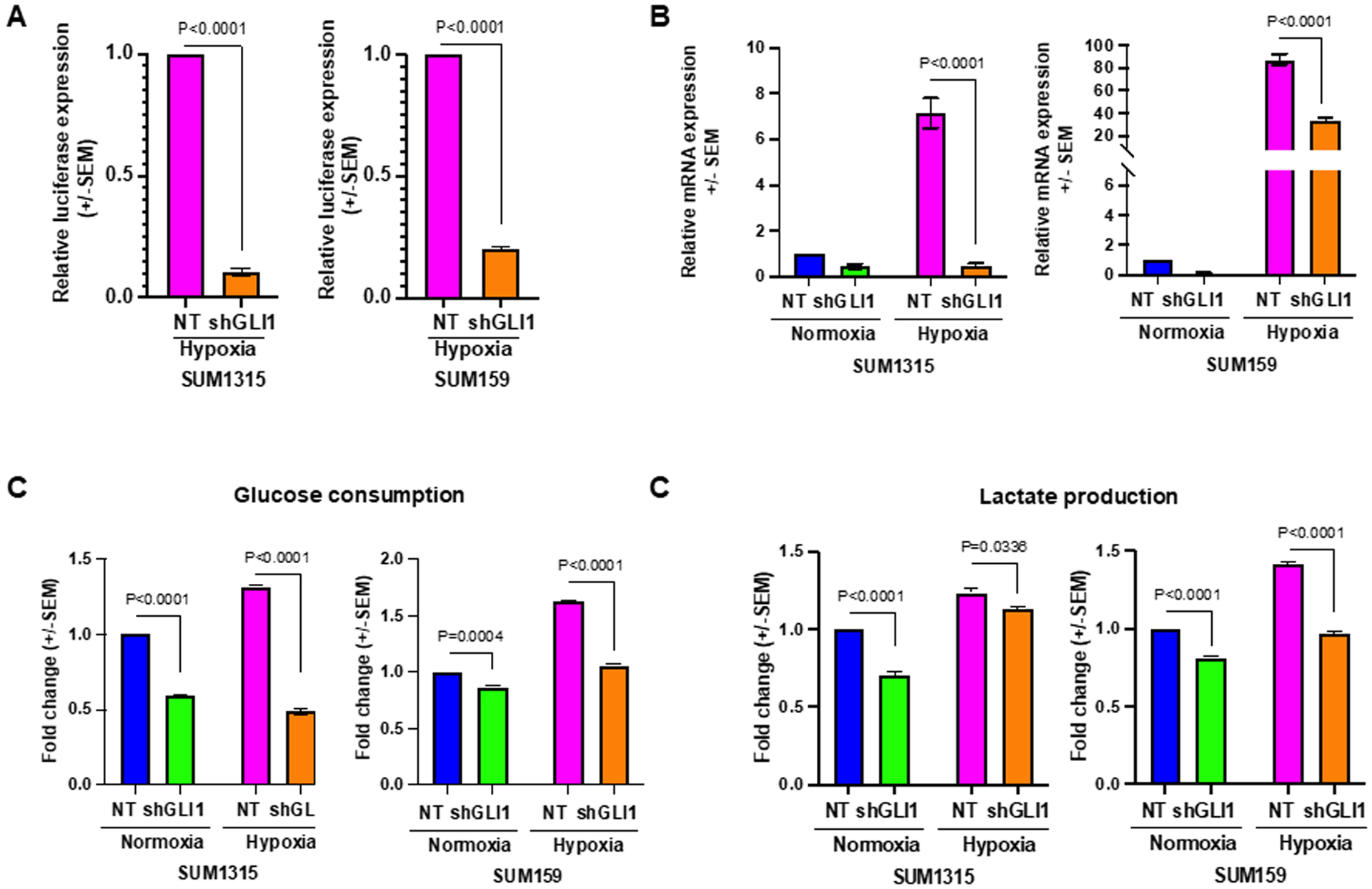

Hh activity reinforces hypoxic response in TNBC cell lines

Elevated Hh activity in hypoxic culture conditions suggests that the pathway likely plays an essential role in sustenance of the cancer cells in a harsh microenvironment. To interrogate the significance of hypoxia-induced upregulation of Hh activity, we stably silenced GLI1 in SUM1315 and SUM159 cells and evaluated the transcription activity of HIF-1α using the HRE-luc reporter in hypoxic conditions (26). Abrogating GLI1 expression led to significant decrease in HRE-luc activity (Figure 3A). We also assessed the expression of hypoxia gene target CAIX. While CAIX mRNA expression is upregulated in hypoxia, abrogating GLI1 significantly decreased its steady-state transcript levels in SUM1315 and SUM159 cells (Figure 3B). HIF-1α navigates a shift of cancer cell metabolism by increasing reliance on anaerobic glycolysis (27). Glucose consumption and lactate production are key features of this cellular metabolic alteration (28). We see that silencing GLI1 led to a decrease in cellular glucose consumption (Figure 3C) and lactate production compared to the non-target control cells in hypoxic culture conditions, (Figure 3D), indicating that Hh/GLI activity perpetuates a robust hypoxia response in breast cancer cells.

Figure 3. Inhibition of Hh/GLI signaling impairs cellular adaptation in hypoxic conditions.

(A) Cells stably abrogated for GLI1 expression support significantly reduced HRE-luciferase reporter activity in SUM1315 and SUM159 cells, in hypoxia. (B) Classical HIF-1α target gene CAIX is upregulated in hypoxic conditions. Stable GLI1 silencing alleviates this increase. (C) In hypoxia, glucose consumption is significantly elevated. Stable GLI1 silencing abrogates elevated glucose consumption in hypoxia. (D) Elevated lactate production in hypoxia is mitigated by stable GLI1 silencing. Statistical significance was determined with a two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test for each condition. Statistical significance was determined with two-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test, only comparison between control and shGLI1 groups in normoxia and hypoxia conditions are shown. All error bars depict the SEM.

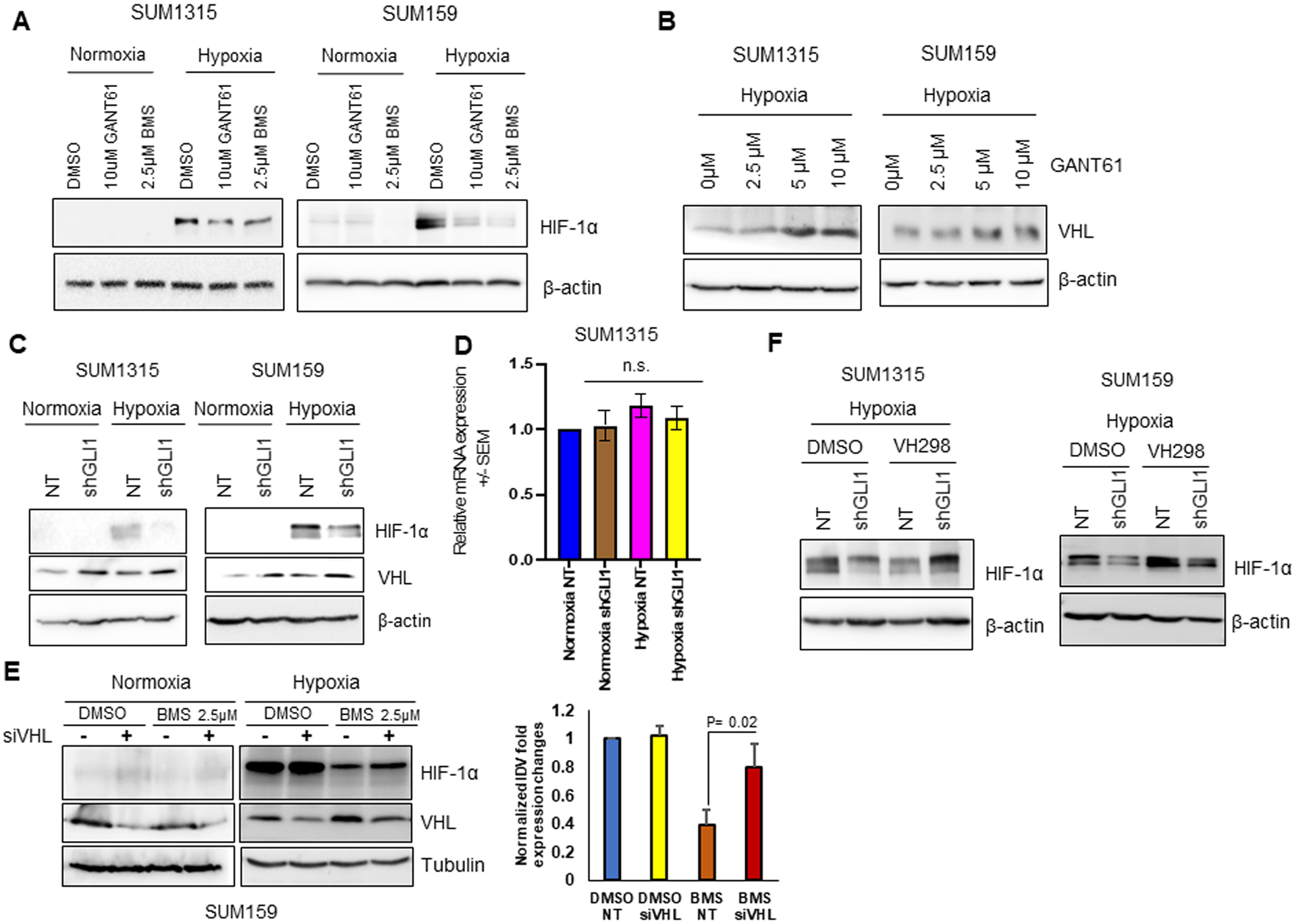

Hh signaling pathway increases HIF-1α transcription factor stability in VHL-dependent mechanism

HIF-1α protein stability underlies an effective adaptive response in hypoxic cells (4). In order to evaluate the effect of Hh/GLI activity on HIF-1α, we inhibited Hh/GLI using two inhibitors that act at non-overlapping nodes in the Hh pathway. While GANT61 inhibits binding of GLI to DNA (29), BMS-833923 (BMS) targets the SMO regulatory molecule (30). HIF-1α protein is stably expressed in hypoxic conditions; however, inhibition of Hh leads to decreased cellular accumulation of HIF-1α in SUM1315 and SUM159 cells (Figure 4A). Building upon this lead, we enquired the cellular levels of VHL, a well-known regulator of HIF-1α protein stability. We found that inhibiting Hh activity using GANT61 led to increased VHL protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner in SUM1315 and SUM159 (Figure 4B). In agreement with this, silencing GLI1 led to increased VHL levels in normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Figure 4C). Hh inhibition did not alter VHL transcript levels (Figure 4D). To evaluate if Hh-mediated HIF-1α protein stability is VHL-dependent, we silenced VHL using siRNA and modulated Hh activity using BMS in SUM159 cells. Silencing VHL in the context of Hh inhibition (BMS-treated cells) allowed for modestly greater accumulation of HIF-1α in hypoxic conditions. (Figure 4E). To rigorously solidify the role of VHL, we used VH298, a VHL inhibitor that covalently binds to VHL (31). Cells stably silenced for GLI1 cells showed a robust recovery of HIF-1α (Figure 4F). Additionally, to verify that Hh-mediated HIF-1α protein stability is dependent on VHL mediated proteasomal degradation, we used lactacystin, a 26S proteasomal inhibitor. HIF-1α protein levels are recovered in GLI1 silenced cells following proteasome inhibition (Supplementary Figure 2). Taken together, we established that Hh-mediated HIF-1α accumulation is reliant upon inhibiting VHL.

Figure 4. Hh signaling increases HIF-1α transcription factor stability in a VHL-dependent mechanism.

(A) Hh pathway inhibition by GANT61 and BMS leads to decrease in accumulation of HIF-1α protein in SUM1315 and SUM159 cells in hypoxia. (B) GANT61 increased expression of VHL protein in hypoxic condition, in a dose-dependent manner. (C-D) Hh pathway inhibition in SUM1315 and SUM159 stably knocked-down for GLI1 results in (C) decrease in accumulation of HIF-1α protein in hypoxic condition (D) no changes in VHL mRNA expression (n.s. – non-significant). (E) Hh pathway inhibition by BMS leads to increase in accumulation of HIF-1α protein in SUM159 cells silenced for VHL using siRNA in hypoxia. Graph represents normalized densitometric quantification. (F) VH298 led to increased accumulation of HIF-1α protein in SUM1315 and SUM159 cells stably knocked-down for GLI1 in hypoxia compared to the control.

Tuning Hh activity in 4T1 cells notably impacts HIF-1α accumulation in hypoxia

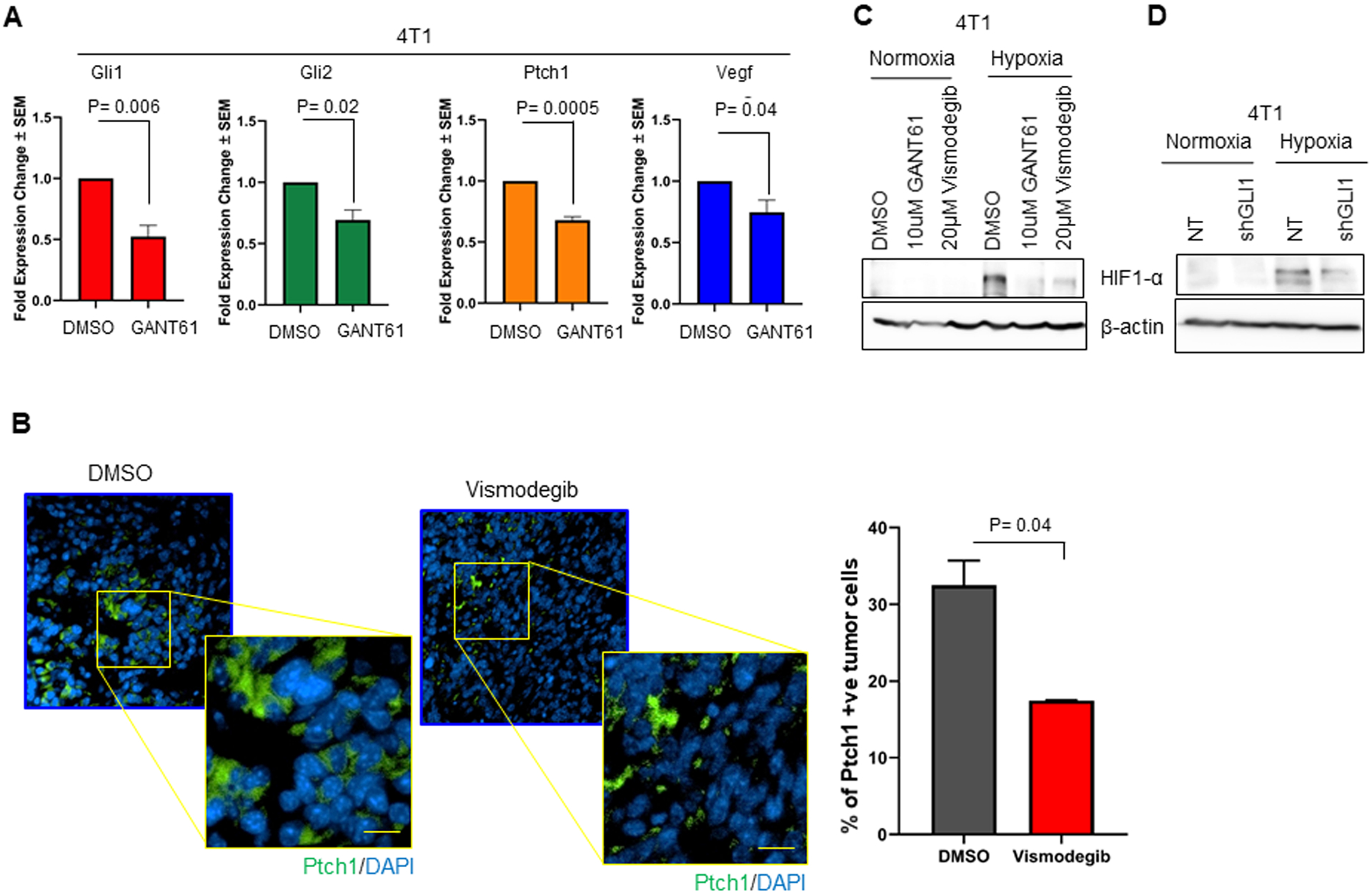

Putting these data into perspective, we assessed the effect of tuning Hh/Gli activity on 4T1 cells. GANT61 significantly decreased the expression of Gli1 transcription targets Vegf, Ptch1, Gli1, and Gli2 in 4T1 cells (Figure 5A), while exogenous treatment with SHH ligand upregulated the expression of these Gli1 transcription targets (Supplementary Figure 3). In addition, inhibiting Hh signaling in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice led to remarkable reduction of Ptch1-positive cells (Figure 5B). Taken together, our findings indicate that the 4T1 cells are acutely Hh-responsive. Inhibiting Hh with GANT61 and Vismodegib brought about a significant decrease in HIF-1α accumulation (Figure 5C). This was phenocopied by stable silencing of Gli1 (Figure 5D). As such, tuning Hh activity in 4T1 cells notably impacts HIF-1α accumulation in hypoxia.

Figure 5. Inhibition of Hh signaling in 4T1 syngeneic tumor mouse model.

(A) Transcript levels of Vegf, Ptch1, Gli1, and Gli2 are significantly decreased in 4T1 cells treated with the GLI inhibitor, GANT61. Statistical significance was determined with one-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Data depicted as fold change +/− SEM. (B) Vismodegib treatment decreased the number of Ptch1-positive tumor cells relative to tumors from mice administered vehicle control. Ptch1 was visualized by immunofluorescence. The graph represents the percentage of quantified Ptch1 positive tumor cells per total number of tumor cells per field. (C) 4T1 cells inhibited for Hh signaling with GANT61 and Vismodegib demonstrate a marked decrease in HIF-1α accumulation in hypoxic condition. (D) 4T1 shGLI1 cells show decreased accumulation of HIF-1α in hypoxic conditions compared to NT control cells.

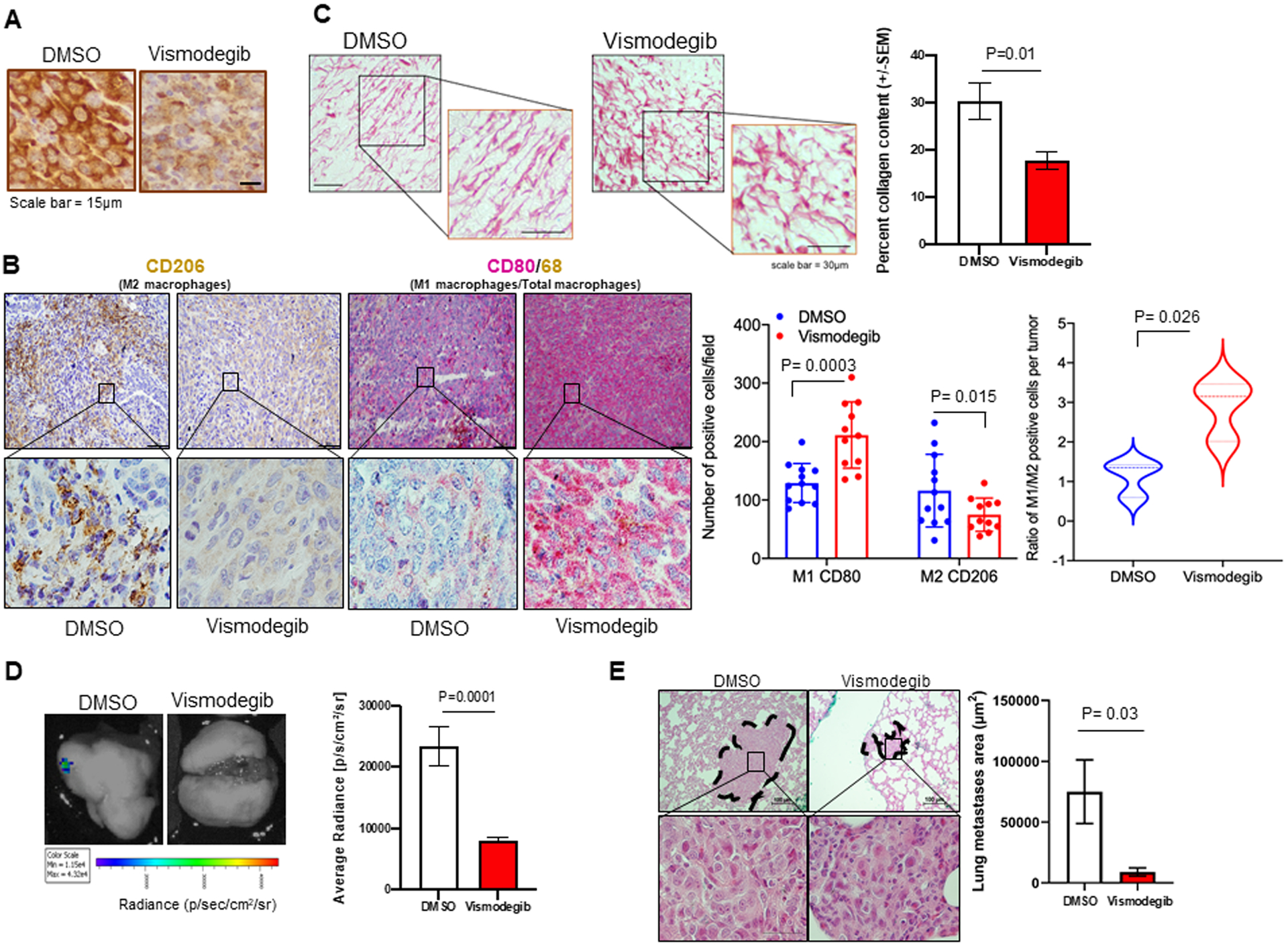

Vismodegib remodels the extracellular matrix and decreases pulmonary metastasis

Thus far, our data indicate that hypoxia exacerbates Hh/GLI transcriptional activity that in turn, enables robust HIF-signaling. Vismodegib decreases tumor hypoxia in the 4T1-Balb/c preclinical model, suggesting that Hh pathway may function as a modifier of temporal changes in tumor hypoxia. In order to complement temporal changes in hypoxia, we sought to further analyze the tumors histologically at the end of treatment. Qualitative CAIX immunohistochemical analysis informs about the extent of hypoxia in the tissue (32,33). These findings are in agreement with the [18F]-FMISO retention data. We assessed the expression of CAIX as an indicator of hypoxic signaling in the 4T1 tumors. In agreement with the overall dampened HIF-1α response, we see that while 4T1 tumors from the vehicle control group show evidence of robust hypoxia, tumors from the 4T1 Vismodegib-treated group show characteristic CAIX staining (Figure 6A). Hypoxic tumors are characterized by abnormal vasculature due to temporal changes in oxygenation status, leading to the formation of disorganized and leaky blood vessels during tumor progression (34). We have previously shown that Hh enhances pro-angiogenic signaling (35). We examined these 4T1 tumors for vascularity by staining for isolectin B4. Vehicle control tumors show large diameter blood vessels and significantly higher microvessel density compared to the Vismodegib-treated tumors (Supplementary Figure 4A). In several tumor models, it has been shown that macrophages can infiltrate both oxygenized perivascular regions as well as hypoxic tumor areas. Severe tumor hypoxia and a high density of hypoxic tumor-associated macrophages have been shown to correlate with a decreased survival rate (36). Vismodegib altered the phenotype of tumor-infiltrating macrophages. In contrast to vehicle-treated tumors, Vismodegib-treated tumors showed significantly fewer CD206-positive M2 macrophages concomitant with increased abundance of CD80-positive M1 macrophages (Figure 6B). We also evaluated the tumors for the organization of collagen by picrosirius red staining. Collagen is the most abundant structural component of the extracellular matrix and an important determinant of tumor invasion and metastasis (37,38). Vismodegib-treated tumors had random and misaligned collagen fibers compared to continuous and aligned fibers in untreated tumors, indicating that Vismodegib alters collagen crosslinking within the extracellular matrix of the tumor (Figure 6C, Supplementary Figure 4B). Aligned with these results, lungs from Vismodegib-treated mice show significantly decreased bioluminescent lung metastases (Figure 6D) and remarkably smaller microscopic lung metastases (Figure 6E). Overall, our data indicates that Vismodegib remarkably remodels the hypoxia-associated TME and decreases metastasis to the lungs.

Figure 6. Vismodegib alters the tumor microenvironment and decreases metastasis.

(A) Primary tumor IHC staining for CAIX shows decrease in expression in Vismodegib treated mice. (B) Tumor tissues were stained for CD206 (M2 macrophages). Serial sections were also stained by dual-color immunohistochemistry for CD80 (M1 macrophages) and CD68 (pan macrophage marker). Vismodegib significantly decreased the abundance of tumor-infiltrating M2 macrophages and increased the numbers of M1 macrophages. (C) Vismodegib alters the collagen fiber alignment quantified by collagen content using picrosirius red staining. Statistical significance was determined using a t-test. All error bars depict the SEM. (D) Representative images of ex-vivo lung BLI on Day 34 post injection. Ex-vivo BLI imaging of lungs from Vismodegib-treated mice shows decreased metastasis compared to vehicle control quantified using average radiance. (E) H&E staining of mouse lungs showing larger metastatic foci in DMSO control group compared to Vismodegib treated mice group. Graph represents lunge metastases area in mm2 per group. Statistical significance was determined with one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test. All error bars depict the SEM.

Discussion

The ability of tumor cells to adapt to hypoxia determines their ability to survive the formidable hypoxic microenvironment. HIFs play a critical role in the survival of cancer cells by regulating genes that enable angiogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, drug resistance, and survival (39). Breast cancer can metastasize to the lungs, bone, brain, and liver (40). The presentation of metastasis drastically reduces survival in breast cancer patients. In breast cancer, hypoxia is known to promote metastasis (41,42).

Aberrant re-activation of Hh signaling is a feature of multiple tumor types, including breast cancer, and this is recognized to impact malignant characteristics of the tumor cells, as well as elicit enhanced vasculature and alter the tumor immune microenvironment (35,43). Hypoxia is an integral feature of growing solid tumors; however, thus far, the impact of the Hh pathway on the hypoxic tumor niche and enabling cancer cell adaptation to the hypoxic microenvironment remains unexplored.

In this study, we used [18F]-FMISO-PET imaging to quantitate longitudinal changes in tumor hypoxia. In order to specifically query the role of Hh activity in shaping the hypoxic TME, we administered Vismodegib in a pre-clinical mammary tumor model. To our knowledge, this is the first study to establish that Hh pathway inhibition antagonizes the progressive hypoxic TME and interferes with VHL-mediated HIF-1α accumulation in the tumor cells.

Previous studies with inhibition of HIF activity by RNA interference or digoxin found a decrease in both primary tumor growth and lung metastasis in mice bearing MDA-MB-231 xenografts (41). Hh signaling inhibition by Vismodegib also sensitized basal cell and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells to radiation thereapy. However, in our immune competent preclinical model, Vismodegib mitigated tumor hypoxia without an appreciable difference in tumor size. We previously reported that Vismodegib alters the tumor immune portfolio from an immunosuppressive to an immune reactive type (44). Here we show that tumors from Vismodegib-treated mice show a significant decrease in the immunosuppressive (M2) macrophages coupled to an increase in the population of anti-tumor M1 macrophages infiltrating the tumor. While a hypoxic tumor milieu is associated with suppressive immune cells, data suggests that influenced by the tumor milieu (independent of hypoxia), monocytes can evolve into MHC-IIlo M2-like TAM or MHC-IIhi M1-like TAM. Importantly, MHC-IIlo TAM gravitate towards hypoxic regions where they upregulate hypoxia-regulated genes and aid in angiogenesis (36). Moreover, the acidic environment within the tumor due to accumulation of lactate also supports immune cell dysfunction (45). We have previously demonstrated that Hh/GLI activity programs macrophages to be alternative polarized to an M2 phenotype (44). Thus, the reduced infiltration by M2 macrophages in Vismodegib-treated tumors is likely attributable to inhibition of Hh/GLI activity in the macrophages.

In murine breast cancer models, hypoxia facilitates release of lysyl oxidase (LOX) by tumor cells. LOX is a HIF-1α transcriptional target that remodels collagen. This remodeling can occur in the proximity of the tumor and also in the extracellular matrix of remote sites, supporting the establishment of a “pre-metastatic niche” (46). In our murine model, Vismodegib crafted a distinct, randomly networked architecture of collagen in the tumor. Immune evasion and migration along collagen fibers are critical steps to metastasis; it is likely that Vismodegib antagonizes tumor progression by mitigating tumor hypoxia, consequently affecting immune cell function and collagen crosslinking.

We determined that Hh inhibition compromises HIF-1α protein stability in a VHL-dependent manner. In hypoxia, VHL is moderated by a negative feedback loop through HIF binding at the HRE site in the VHL promoter (47). In the current study, we found no significant changes in VHL mRNA expression with Hh inhibition, although we registered an increase in VHL protein levels in hypoxic conditions in breast cancer cells. Previous studies by Cho et al., showed that VHL inhibits GLI1 nuclear localization and colocalizes with GLI1 by GST pull down assay, implicating a role for VHL-mediated regulation of Hh (48). Our data indicates that Hh activity post-translationally regulates VHL, although whether Hh plays a role in post-translational modification of VHL remains unexplored.

Hypoxia is a known indicator of adverse outcomes in breast cancer patients (49). Hypoxic TME presents as a barrier for effectiveness of common cancer treatments. Hypoxic cancer cells are resistant to radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy (50,51). Therefore, altering TME by mitigating hypoxia might make the tumor more susceptible to these therapies. Our data indicates that Vismodegib moderates hypoxia in a pre-clinical mammary cancer model, providing a supporting rationale to use Vismodegib, which is already in clinic for acute myeloid leukemia and advanced basal cell carcinoma (52), for breast cancer patients that present with elevated tumor hypoxia. As such, the use of Vismodegib to target hypoxic tumors presents as an opportunity to decrease metastasis in breast cancer. Furthermore, using a clinically relevant imaging method for hypoxia, such as [18F]-FMISO-PET imaging, lends us the possibility to longitudinally monitor patients receiving cancer treatment and potentially could indicate timing of reduced hypoxia to introduce secondary combination therapies.

Solid tumors are often challenged with a hypoxic microenvironment due to increased demand for oxygen in the proliferating cells. Moreover, the proportions of hypoxic tumor cells in the primary tumor strongly correlate with the incidence of metastasis, treatment resistance, and poor prognosis. Overall, our study revealed that inhibiting Hh signaling ameliorated the tumor hypoxic landscape with a concomitant decrease in metastasis. Molecularly, we determined that Hh blockade significantly mitigated the ability of tumor cells to adapt to hypoxia. Thus, the collective findings establish a novel perspective on the benefit of Hh inhibitors in impeding hypoxia-mediated tumor progression and metastasis. Using clinically relevant FMISO-PET imaging presents the opportunity to translate this modality to monitor response to Vismodegib therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the following sources: Department of Defense (W81XWH-19-1-0755 and W81XWH-18-1-0036), NCI R01CA169202, The Breast Cancer Research Foundation of Alabama (BCRFA), O’Neal Invests Award, and the CCTS-Radiology voucher - all awarded to L.A. Shevde; R. S. Samant (NCI CA19048 and BX003374 – Merit Review award from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs BLRD service); A. G. Sorace (NCI R01CA240589 and American Cancer Society RSG-18-006-06-CCE). D. Hinshaw is supported on T32 AI007051. The authors would also like to thank the UAB Cyclotron Facility directed by Dr. Suzanne Lapi and the UAB O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Preclinical Imaging Shared Facility supported by NIH grant P30 CA013148.

Abbreviations

- PO2

Pressure of Oxygen

- Hg

Mercury

- HREs

Hypoxia Response Elements

- PHD

Proline Hydroxylase

- VHL

Von Hippel Lindau

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- Mdm2

Mouse Double Minute 2 Homolog

- Hsp90

Heat Shock Protein 90

- Hh

Hedgehog

- EMT

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

- DHH

Desert Hedgehog

- IHH

Indian Hedgehog

- SHH

Sonic Hedgehog

- PTCH1

Pass Transmembrane Protein Receptors

- SMO

Smoothened

- GLI

Glioma associated oncogene homolog

- FMISO

[18F]-fluoromisonidazole

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- SUV

Standard Uptake Value

- BLI

Bioluminescence

- TME

Tumor Microenvironment

- HIF- 1α

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha

- TNBC

Triple Negative Breast Cancer

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Vaupel P (2009) Prognostic potential of the pre-therapeutic tumor oxygenation status. Adv Exp Med Biol 645, 241–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaupel P, Mayer A, and Höckel M (2004) Tumor Hypoxia and Malignant Progression. in Methods in Enzymology, Academic Press. pp 335–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semenza GL (2016) The hypoxic tumor microenvironment: A driving force for breast cancer progression. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863, 382–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semenza GL (2010) Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene 29, 625–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaelin WG Jr., and Ratcliffe PJ (2008) Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell 30, 393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masoud GN, and Li W (2015) HIF-1α pathway: role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B 5, 378–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riobo-Del Galdo NA, Lara Montero Á, and Wertheimer EV (2019) Role of Hedgehog Signaling in Breast Cancer: Pathogenesis and Therapeutics. Cells 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das S, Samant RS, and Shevde LA (2011) Hedgehog signaling induced by breast cancer cells promotes osteoclastogenesis and osteolysis. J Biol Chem 286, 9612–9622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao Z, Han L, Chen Y, He F, Sun B, kamar S, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Wang C, and Yang Z (2018) Hedgehog signalling in the tumourigenesis and metastasis of osteosarcoma, and its potential value in the clinical therapy of osteosarcoma. Cell Death & Disease 9, 701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Amato C, Rosa R, Marciano R, D’Amato V, Formisano L, Nappi L, Raimondo L, Di Mauro C, Servetto A, Fulciniti F, Cipolletta A, Bianco C, Ciardiello F, Veneziani BM, De Placido S, and Bianco R (2014) Inhibition of Hedgehog signalling by NVP-LDE225 (Erismodegib) interferes with growth and invasion of human renal cell carcinoma cells. British Journal of Cancer 111, 1168–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shevde LA, and Samant RS (2014) Nonclassical hedgehog-gli signaling and its clinical implications. International Journal of Cancer 135, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onishi H, Kai M, Odate S, Iwasaki H, Morifuji Y, Ogino T, Morisaki T, Nakashima Y, and Katano M (2011) Hypoxia activates the hedgehog signaling pathway in a ligand-independent manner by upregulation of Smo transcription in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci 102, 1144–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao C-W, Zheng C, and Wang L (2020) Down-regulation of FOXR2 inhibits hypoxia-driven ROS-induced migration and invasion of thyroid cancer cells via regulation of the hedgehog pathway. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology 47, 1076–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhuria V, Xing J, Scholta T, Bui KC, Nguyen MLT, Malek NP, Bozko P, and Plentz RR (2019) Hypoxia induced Sonic Hedgehog signaling regulates cancer stemness, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and invasion in cholangiocarcinoma. Exp Cell Res 385, 111671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park SH, Jeong S, Kim BR, Jeong YA, Kim JL, Na YJ, Jo MJ, Yun HK, Kim DY, Kim BG, Lee DH, and Oh SC (2020) Activating CCT2 triggers Gli-1 activation during hypoxic condition in colorectal cancer. Oncogene 39, 136–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asano A, Ueda S, Kuji I, Yamane T, Takeuchi H, Hirokawa E, Sugitani I, Shimada H, Hasebe T, Osaki A, and Saeki T (2018) Intracellular hypoxia measured by 18F-fluoromisonidazole positron emission tomography has prognostic impact in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research 20, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whisenant JG, Peterson TE, Fluckiger JU, Tantawy MN, Ayers GD, and Yankeelov TE (2013) Reproducibility of static and dynamic (18)F-FDG, (18)F-FLT, and (18)F-FMISO MicroPET studies in a murine model of HER2+ breast cancer. Mol Imaging Biol 15, 87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorace AG, Syed AK, Barnes SL, Quarles CC, Sanchez V, Kang H, and Yankeelov TE (2017) Quantitative [(18)F]FMISO PET Imaging Shows Reduction of Hypoxia Following Trastuzumab in a Murine Model of HER2+ Breast Cancer. Mol Imaging Biol 19, 130–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee ST, and Scott AM (2007) Hypoxia Positron Emission Tomography Imaging With 18F-Fluoromisonidazole. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine 37, 451–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamane T, Aikawa M, Yasuda M, Fukushima K, Seto A, Okamoto K, Koyama I, and Kuji I (2019) [18F]FMISO PET/CT as a preoperative prognostic factor in patients with pancreatic cancer. EJNMMI Research 9, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming IN, Manavaki R, Blower PJ, West C, Williams KJ, Harris AL, Domarkas J, Lord S, Baldry C, and Gilbert FJ (2015) Imaging tumour hypoxia with positron emission tomography. Br J Cancer 112, 238–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das S, Harris LG, Metge BJ, Liu S, Riker AI, Samant RS, and Shevde LA (2009) The hedgehog pathway transcription factor GLI1 promotes malignant behavior of cancer cells by up-regulating osteopontin. The Journal of biological chemistry 284, 22888–22897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lama-Sherpa TD, Lin VTG, Metge BJ, Weeks SE, Chen D, Samant RS, and Shevde LA (2020) Hedgehog signaling enables repair of ribosomal DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Research [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Z, Li XF, Zou H, Sun X, and Shen B (2017) (18)F-Fluoromisonidazole in tumor hypoxia imaging. Oncotarget 8, 94969–94979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heppner GH, Miller FR, and Shekhar PM (2000) Nontransgenic models of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2, 331–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emerling BM, Weinberg F, Liu JL, Mak TW, and Chandel NS (2008) PTEN regulates p300-dependent hypoxia-inducible factor 1 transcriptional activity through Forkhead transcription factor 3a (FOXO3a). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 2622–2627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al Tameemi W, Dale TP, Al-Jumaily RMK, and Forsyth NR (2019) Hypoxia-Modified Cancer Cell Metabolism. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin X, Xiao Z, Chen T, Liang SH, and Guo H (2020) Glucose Metabolism on Tumor Plasticity, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Frontiers in Oncology 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agyeman A, Jha BK, Mazumdar T, and Houghton JA (2014) Mode and specificity of binding of the small molecule GANT61 to GLI determines inhibition of GLI-DNA binding. Oncotarget 5, 4492–4503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibson MK, Zaidi AH, Davison JM, Sanz AF, Hough B, Komatsu Y, Kosovec JE, Bhatt A, Malhotra U, Foxwell T, Rotoloni CL, Hoppo T, and Jobe BA (2013) Prevention of Barrett Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma by Smoothened Inhibitor in a Rat Model of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Annals of Surgery 258, 82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frost J, Galdeano C, Soares P, Gadd MS, Grzes KM, Ellis L, Epemolu O, Shimamura S, Bantscheff M, Grandi P, Read KD, Cantrell DA, Rocha S, and Ciulli A (2016) Potent and selective chemical probe of hypoxic signalling downstream of HIF-α hydroxylation via VHL inhibition. Nat Commun 7, 13312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bao B, Groves K, Zhang J, Handy E, Kennedy P, Cuneo G, Supuran CT, Yared W, Rajopadhye M, and Peterson JD (2012) In Vivo Imaging and Quantification of Carbonic Anhydrase IX Expression as an Endogenous Biomarker of Tumor Hypoxia. PLOS ONE 7, e50860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wykoff CC, Beasley N, Watson PH, Campo L, Chia SK, English R, Pastorek J, Sly WS, Ratcliffe P, and Harris AL (2001) Expression of the Hypoxia-Inducible and Tumor-Associated Carbonic Anhydrases in Ductal Carcinoma in Situ of the Breast. The American Journal of Pathology 158, 1011–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forster JC, Harriss-Phillips WM, Douglass MJ, and Bezak E (2017) A review of the development of tumor vasculature and its effects on the tumor microenvironment. Hypoxia (Auckl) 5, 21–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris LG, Pannell LK, Singh S, Samant RS, and Shevde LA (2012) Increased vascularity and spontaneous metastasis of breast cancer by hedgehog signaling mediated upregulation of cyr61. Oncogene 31, 3370–3380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laoui D, Van Overmeire E, Di Conza G, Aldeni C, Keirsse J, Morias Y, Movahedi K, Houbracken I, Schouppe E, Elkrim Y, Karroum O, Jordan B, Carmeliet P, Gysemans C, De Baetselier P, Mazzone M, and Van Ginderachter JA (2014) Tumor hypoxia does not drive differentiation of tumor-associated macrophages but rather fine-tunes the M2-like macrophage population. Cancer Res 74, 24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Natarajan S, Foreman KM, Soriano MI, Rossen NS, Shehade H, Fregoso DR, Eggold JT, Krishnan V, Dorigo O, Krieg AJ, Heilshorn SC, Sinha S, Fuh KC, and Rankin EB (2019) Collagen Remodeling in the Hypoxic Tumor-Mesothelial Niche Promotes Ovarian Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Research 79, 2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grossman M, Ben-Chetrit N, Zhuravlev A, Afik R, Bassat E, Solomonov I, Yarden Y, and Sagi I (2016) Tumor Cell Invasion Can Be Blocked by Modulators of Collagen Fibril Alignment That Control Assembly of the Extracellular Matrix. Cancer Research 76, 4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Semenza GL (2012) Molecular mechanisms mediating metastasis of hypoxic breast cancer cells. Trends Mol Med 18, 534–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siegel RL, Miller KD, and Jemal A (2016) Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 66, 7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H, Wong CCL, Wei H, Gilkes DM, Korangath P, Chaturvedi P, Schito L, Chen J, Krishnamachary B, Winnard PT, Raman V, Zhen L, Mitzner WA, Sukumar S, and Semenza GL (2012) HIF-1-dependent expression of angiopoietin-like 4 and L1CAM mediates vascular metastasis of hypoxic breast cancer cells to the lungs. Oncogene 31, 1757–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Gilkes DM, and Semenza GL (2013) Role of hypoxia-inducible factors in breast cancer metastasis. Future Oncol 9, 1623–1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris LG, Samant RS, and Shevde LA (2011) Hedgehog signaling: networking to nurture a promalignant tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer Res 9, 1165–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanna A, Metge BJ, Bailey SK, Chen D, Chandrashekar DS, Varambally S, Samant RS, and Shevde LA (2019) Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling reprograms the dysfunctional immune microenvironment in breast cancer. OncoImmunology 8, 1548241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harmon C, O’Farrelly C, and Robinson MW (2020) The Immune Consequences of Lactate in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol 1259, 113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Nicolau M, Dornhofer N, Kong C, Le QT, Chi JT, Jeffrey SS, and Giaccia AJ (2006) Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature 440, 1222–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Łuczak MW, Roszak A, Pawlik P, Kędzia H, Lianeri M, and Jagodziński PP (2011) Increased expression of HIF-1A and its implication in the hypoxia pathway in primary advanced uterine cervical carcinoma. Oncol Rep 26, 1259–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho HK, Kim SY, Kim KH, Kim HH, and Cheong J (2013) Tumor suppressor protein VHL inhibits Hedgehog-Gli activation through suppression of Gli1 nuclear localization. FEBS Lett 587, 826–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muz B, de la Puente P, Azab F, and Azab AK (2015) The role of hypoxia in cancer progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Hypoxia (Auckl) 3, 83–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graham K, and Unger E (2018) Overcoming tumor hypoxia as a barrier to radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy in cancer treatment. Int J Nanomedicine 13, 6049–6058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eckert F, Zwirner K, Boeke S, Thorwarth D, Zips D, and Huber SM (2019) Rationale for Combining Radiotherapy and Immune Checkpoint Inhibition for Patients With Hypoxic Tumors. Frontiers in immunology 10, 407–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie H, Paradise BD, Ma WW, and Fernandez-Zapico ME (2019) Recent Advances in the Clinical Targeting of Hedgehog/GLI Signaling in Cancer. Cells 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.