Abstract

A collection of three hundred thirty rotavirus-positive stool samples from children with diarrhea in the southern and eastern regions of Ireland between 1997 and 1999 were submitted to the Molecular Diagnostics Unit of the Cork Institute of Technology, Cork, Ireland, for investigation. These strains were characterized by several methods, including polyacrylamide gel electropherotyping and G and P genotyping. A subset of the G types was confirmed by nucleic acid sequencing. The most prevalent types found in this collection included G1P[8] (n = 106; 32.1%), G2P[4] (n = 94; 28.5%), and G4P[8] (n = 37; 11.2%). Novel strains were also detected, including G1P[4] (n = 19; 5.8%), and G4P[4] (n = 2; 0.6%). Interestingly, mixed infections accounted for 18.8% (n = 62) of the total collection, with only 3% (n = 10) which were not G and/or P typeable. Significantly, six G8 and five G9 strains were identified as part of mixed infections. These strains have not previously been identified in Irish children, suggesting a greater diversity in rotavirus strains currently circulating in Ireland.

Rotavirus is the primary etiological agent of gastroenteritis in infants and young children worldwide (26). In developing countries, it is estimated that rotavirus is responsible for one-third of all diarrhea-associated hospitalizations and 873,000 deaths annually (8, 23). In industrialized countries, where mortality due to rotavirus is low, infection is widespread and nearly all children experience an episode of rotavirus diarrhea in the first 5 years of life (42, 50). National surveillance data from the Infoscan platform confirmed that rotavirus is the most common pathogen among Irish children hospitalized for gastroenteritis (10). Availability of a rotavirus vaccine would have the potential to reduce the impact of rotavirus disease in these settings (7, 25, 48).

Characterization of the rotavirus genome by gel electrophoresis is a technique widely used to distinguish virus isolates and monitor virus transmission (45). Migration of the double-stranded RNA segments in polyacrylamide gels is the most frequently used method, generating distinct electropherotype patterns. Serotypes are defined by antigen-based methods (e.g., enzyme immunoassays) or molecular methods, including reverse transcriptase (RT)-mediated PCR. The combined use of electropherotype and serotyping protocols is useful in defining the epidemiology of rotavirus and identifying any novel strains in circulation (3).

A dual system of reporting rotavirus serotypes exists due to the neutralizing response evoked by two viral proteins, VP7 and VP4 (15). The VP7-related serotypes are designated G types, and those derived from VP4 are described as P types. To date, 14 G serotypes have been defined by neutralization assays and 10 of these have been identified in humans (13, 44). Genetic studies on human rotavirus gene segment 4 have revealed 20 different P genotypes, and at least 7 of these were confirmed by serological assay (9, 32). An association between certain G and P types has been observed (22).

Extensive epidemiological studies in several health care systems characterizing rotavirus strains have identified the prevalent serotypes circulating in children within different populations. The predominating G types were G1 to G4 (5, 19, 38, 49). Recently, these strains were also confirmed in a small group of rotavirus isolates from Irish children presenting with diarrhea (34). The first licensed human rotavirus vaccine, the rhesus rotavirus vaccine, was withdrawn recently because of an association between vaccination and increased rates of intussusception among vaccine recipients (6). This vaccine was formulated to produce serotype-specific protection against the four common serotypes, G1 to G4 (15). However, other, unconventional serotypes are now being reported, including G5, G8, and G10 in Brazil (1, 29, 44) and G9 in Bangladesh (49), India, and the United States (12, 37, 38). Serotype G8 has also been detected in the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Australia (11, 35, 46). The efficacy of the recently suspended rhesus vaccine is unknown in these settings, and future candidate rotavirus vaccines may need to incorporate other serotypes.

To extend these observations to a larger collection of 330 Irish rotavirus strains, we examined the distribution of G and P types by molecular methods and polyacrylamide gel electropherotyping. A higher proportion of mixed-type infections, together with unconventional serotypes, were noted, suggesting that a complex pool of rotavirus exists which has not been identified previously.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rotavirus detection.

Three hundred thirty fecal samples from Irish children with ages ranging from 1 month to 2 years were obtained from four large centers in the southern and eastern regions of Ireland. The samples were identified as rotavirus positive by antigen detection strategies, including enzyme immunoassays (Abbott Laboratories, Dublin, Ireland) and latex agglutination tests (Orion Diagnostics, Espoo, Finland). Fecal filtrates were stored at −20°C prior to analysis.

RNA extraction and polyacrylamide gel electropherotyping.

The double-stranded RNA segmented genome characteristic of rotavirus was isolated from samples using a standard phenol-chloroform extraction method with ethanol precipitation (17). Samples were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and RNA was treated with DNase 1 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, East Sussex, United Kingdom) to remove contaminating genomic DNA. Electropherotypes of strains were determined using a 10% polyacrylamide gel with a discontinuous buffer system (27), followed by silver staining by the method of Herring et al. (21).

Rotavirus typing.

To determine the G and P types, RT-PCR assays were performed. Initially, 1,062-bp (full-length) gene segment 9, encoding the VP7 glycoprotein in human group A rotaviruses, was amplified using primer Beg9 (5′-GGC TTT AAA AGA GAG AAT TTC CGT CTG G-3′) in the forward direction and primer End9 (5′-GGT CAC ATC ATA CAA TTC TAA TCT AAG-3′) in the reverse direction. This was followed by multiplex heminested PCR using the serotype-specific primers which identify G types (17). To identify P genotypes, a DNA fragment of 867 bp, from gene segment 4 (encoding VP4), was amplified using primers Con2 (5′-ATT TCG GAC CAT TTA TAA CC-3′; forward) and Con3 (5′-TGG CTT CGC CAT TTT ATA GAC A-3′; reverse), followed by genotyping with P-typing primers (14).

Amplified products from the RT-PCR assays were analyzed in conventional 1.5 and 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide (0.1 mg/ml) and visualized over a transilluminator. Tissue culture-adapted control strains included Wa (G1P[8]), DS-1 (G2P[4]), P(G3P[8]), ST3 (G4P[6]), and F45(G9P[8]) (22). These were stored at −80°C.

Nucleic acid sequencing.

A subset of DNA fragments were chosen to confirm the authenticity of the resulting DNA amplicons after G typing. These amplicons were cloned and sequenced using dye terminator chemistry protocols with cycle sequencing (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.). BLAST analysis identified them as G1, G2, and G4 serotypes, confirming the accuracy of the RT-PCR typing protocol.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Three of the VP7-encoded sequences described here were submitted to the GenBank database and assigned accession numbers AF254138, AF254139, and AF254140.

RESULTS

Fecal specimens (330 in total) were collected from Irish infants and children with clinically defined gastroenteritis between 1997 and 1999. Samples were identified as positive for rotavirus by antigen detection strategies, including enzyme immunoassays and latex agglutination tests. Rotavirus RNA was purified and used as the template to characterize each isolate.

Determination of G and P genotypes.

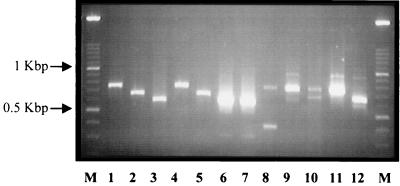

The application of RT-PCR to characterize rotavirus G and P genotypes is a widely used and sensitive technique (9, 13, 31). The distribution of the genotypes found over the 3-year period, as identified by this method, is described in Table 1. Only 3% (n = 10) of the isolates tested could not be assigned a G and/or P type. Three of the four most common strains found worldwide were also found to predominate in this collection. The most prevalent type was G1P[8], accounting for 32.1% (n = 106) of the strains. The frequency of G2P[4] was similar at 28.5% (n = 94), and G4P[8] strains comprised 11.2% (n = 37) of the collection. G3 serotypes were not found as single infections but were identified as components of mixed infections with G1. Of interest was the detection of some uncommon types, including G1P[4] (5.8%) and G4P[4] (0.6%). These strains have not previously been identified in this country. The number of mixed infections was also high, constituting 18.8% (n = 62) of the collection, and several unconventional G and P type combinations were detected, although at low frequency. Mixed infections were present in all age groups from 1 through 24 months. Significantly, G8 and G9 serotypes were identified in the mixed infections. Five G9 strains were found in mixed infections with G4 (Fig. 1, lanes 6 and 7) and associated with a P[8] genotype. These strains were isolated in 1998 (Table 1). G8 serotypes occurred with both G1 and G2 types. One sample was identified by PCR typing as containing G2, G4, and G8 serotypes (Fig. 1, lane 12). The number of G8 mixed infections increased from two in 1997 to four in 1998. No G8 serotypes were detected in 1999, although the number of isolates tested was lower.

TABLE 1.

G and P genotypes of Irish rotavirus strains isolated between 1997 and 1999

| Yr | No. of strains tested | No. of common strains

|

No. of uncommon strains

|

Mixed-infection genotypes (n)a | No. of nontypeable strains | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2P[4] | G1P[8] | G3P[8] | G4P[8] | G1P[4] | G4P[4] | ||||

| 1997 | 123 | 24 | 57 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 1 | G2P[8+4] (1) | 2 |

| G1P[8+4] (4) | |||||||||

| G4P[8+4] (1) | |||||||||

| G1 + G2P[8+4] (9) | |||||||||

| G1 + G2P[4] (3) | |||||||||

| G2 + G8P[4] (1) | |||||||||

| G1 + G4P[8] (6) | |||||||||

| G1 + G3P[8] (2) | |||||||||

| G1 + G8P[8] (1) | |||||||||

| 1998 | 189 | 65 | 44 | 0 | 33 | 12 | 1 | G1P[8+4] (2) | 6 |

| G4P[8+4] (2) | |||||||||

| G1 + G2P[4] (5) | |||||||||

| G4 + G9P[8] (5) | |||||||||

| G2 + G4P[4] (1) | |||||||||

| G1 + G4P[8] (8) | |||||||||

| G1 + G3P[8] (1) | |||||||||

| G2 + G8P[4] (3) | |||||||||

| G2 + G8 + G4P[4] (1) | |||||||||

| 1999 | 18 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | G1P[8+4] (2) | 2 |

| G1 + G2P[8] (1) | |||||||||

| G1 + G2P[4] (3) | |||||||||

| Total no. (%) of strains | 330 | 94 (28.5) | 106 (32.1) | 0 | 37 (11.2) | 19 (5.8) | 2 (0.6) | 62 (18.8) | 10 (3.0) |

n is the number of isolates.

FIG. 1.

Representative G types determined by RT-PCR and detected by conventional 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Lanes: M 100-bp molecular size marker ladder (Roche Biochemicals); 1 and 4, G1 types; 2 and 5, G2 types; 3, G4 type; 6 through 12, mixed G types, including, in lanes 6 and 7, mixed G4 and G9 types; 8, mixed G1 and G3 types; 9, 11, and 12, mixed types with G8; 10, G1 type mixed with G2.

Examination of electropherotypes.

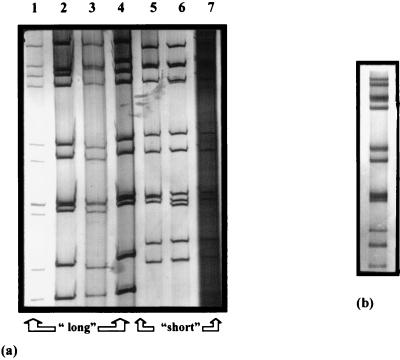

Many studies have used electropherotyping as a means of characterizing rotaviruses (20, 24, 28, 41, 43, 45, 46, 51). While no absolute correlation can be made between the electropherotype and serotype, associations between “short” migration patterns and G2 serotypes have been reported (39, 45). Similarly, the G1, G3, and G4 serotypes are most often associated with a “long” electropherotype pattern. This method is useful for detecting reassortant rotavirus strains and analyzing the heterogeneity of human isolates (40). Electropherotypes were identified for 220 of the 330 isolates in the collection and representative predominant patterns are shown in Fig. 2a. The G1P[8] and G4P[8] strains displayed only long migration patterns (Fig. 2a, lanes 1 and 4). All of the G2P[4] strains had short migration patterns (Fig. 2a, lanes 5 and 6). The unconventional type G1P[4] strains had predominately short electropherotypes (Fig. 2a, lane 7). Two G4P[4] strains displayed short patterns, and mixed infections with G9P[8] and G8P[4] produced long and short electropherotypes, respectively. The mixed types of G1-G3P[8] were associated with a long migration pattern (Fig. 2a, lane 2). Mixed infections of G1 and G2 serotypes were found to have short electropherotypes when the P[4] genotype was associated and long patterns when the P genotype was P[8]. Distinct electropherotype patterns with additional RNA segments were recognized for two strains with mixed G (G1 + G2P[4]) and P (G4P[8+4]) genotypes. An example of the corresponding electropherotype for the latter mixed infection is shown in Fig. 2b.

FIG. 2.

(a) Representative electropherotype variants detected in Irish children. Lanes: 1 through 4, long electropherotype patterns; 5 through 7, short electropherotype patterns. (b) Mixed infection identified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

DISCUSSION

Rotavirus is the principal cause of infantile diarrhea worldwide and has a significant impact on mortality and morbidity in both developing and industrialized countries. Antigenic- and molecular-analysis-based methods available for the characterization of rotavirus have facilitated the identification of the predominant serotypes circulating globally, as well as the detection of other unconventional strains. The degree of diversity among rotavirus strains has been reported to be higher in some regions of the world than in others (44). Uncommon human strains such as G5, G8, G9, and G10 were, until recently, found only in countries such as Brazil and India (12, 29, 37). However, these strains are emerging as global strains (1, 11, 36, 46). This observation has implications for the development of a suitable rotavirus vaccine.

In this study, 330 Irish rotavirus samples were investigated. Analysis of these data indicated a greater diversity in rotavirus strains currently circulating in this country than previously reported (34). Ninety-seven percent (n = 320) of the isolates were assigned a G and P type. The predominant strains identified included serotypes G1P[8] (32.1%), G2P[4] (28.5%), and G4P[8] (11.2%), accounting for 71.8% of this collection, and these are the most common previously reported serotypes (2, 13, 35, 44, 49, 50). However, the detection of unconventional strains and the high incidence of mixed infections (18.8%) were interesting features of this study, suggesting a previously unrecognized and greater diversity among Irish rotavirus infections. Higher numbers of mixed infections may provide a suitable environment for reassortment of rotaviruses, with the inevitable emergence of novel strains.

Furthermore, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis revealed at least seven distinct predominating electropherotype variants characterized in accordance with the scheme proposed by Lourenco et al. (30). Two strains were shown to contain a greater number of double-stranded RNA genomic segments. These data suggest a possible explanation for the emergence of novel strains, including those with unusual combinations of G and P types. In addition, the detection of G9 and G8 serotypes, albeit as mixed infections in this study, is significant when the size of the Irish population is compared to those of other countries where similar isolations were reported (11, 12). The G9P[8] strains were identified as mixed with G4P[8]. According to previous hybridization studies, both of these types belong to subgroup 2 of group A human rotaviruses and it has been suggested that these are related at the genetic level. Coinfection of host cells with strains of these serotype was shown to yield stable reassortants (39). In this case, the corresponding electropherotype was the same for all of the strains, consistent with a long migration pattern.

Serotypes G6, G8, and G10 are more frequently associated with infections in animals, particularly cattle (18, 47). Nevertheless, G8 and G10 types have also been recovered in humans (16, 35, 44). We report here the identification of G8 strains as part of a mixed infection in Irish children. The majority of these were mixed with serotype G2, having a P[4] genotype and displaying a short electropherotype pattern. A single G8-G1P[8] combination was detected with a long electropherotype pattern. Similar strains were formerly identified in other European countries as single infections (16, 46). In Brazil, the G8 serotype was initially reported as part of a mixed infection together with G5 before it emerged as a single-strain infection (44). G8 strains are thought to be reassortants of animal and human viruses (33), and their detection in Ireland may be consistent with our economic dependence on agriculture-based industries. It is unlikely that travel to exotic destinations (such as Brazil or India) occurred.

In conclusion, results of this study highlight important aspects of rotavirus strain diversity in Ireland not previously recognized. We have presented evidence of reassortment between rotavirus strains together with the emergence of novel strains, both aspects of which contribute to the diversity of the existing virus pool. In this study, the presence of mixed infections cannot be attributed to the use of the rhesus rotavirus vaccine, as it was never launched in Ireland. As the number(s) of unconventional strains being discovered increases in different geographical regions, future attempts to develop a suitable vaccine must take this apparent additional rotavirus strain diversity into account. Importantly, the potential genome dynamics of the rotavirus necessitates continuous surveillance to monitor rotavirus infection and facilitate the detection of these novel strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our colleagues at the Departments of Medical Microbiology at Cork University Hospital, Limerick Regional Hospital, Waterford Regional Hospital, and Temple Street Children's Hospital for supplying rotavirus strains. We also thank Jon Gentsch at CDC, Atlanta, Ga., and Jim Grey, Biochemistry Department, Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom, for the kind gifts of the reference strains used. We also acknowledge John Murphy at CIT for technical support and Linda Walsh at the DNA Sequencing Facility, National University of Ireland, Cork, for help with sequencing.

Financial support from Irish Government Scientific Funding Agencies is gratefully acknowledged (grants GTP 96/CR/028 and ARG 98/226). Wyeth Lederle (Ireland) is also thanked for its financial contribution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfredi A A, Leite J P G, Nakagomi O, Kaga E, Woods P A, Glass R I, Gentsch J R. Characterisation of human rotavirus genotype P[8]G5 from Brazil by probe-hybridisation and sequence. Arch Virol. 1996;141:2353–2364. doi: 10.1007/BF01718636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arista S, Vizzi E, Ferraro D, Cascio A, Di Stefano R. Distribution of VP7 serotypes and VP4 genotypes among rotavirus strains recovered from Italian children with diarrhea. Arch Virol. 1997;142:2065–2071. doi: 10.1007/s007050050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arista S, Giovannelli L, Pistoia D, Cascio A, Parea M, Gerna G. Electropherotypes, subgroups and serotypes of human rotavirus strains causing gastroenteritis in infants and young children in Palermo, Italy, from 1985 to 1989. Res Virol. 1990;141:435–448. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(90)90044-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beards G M. Polymorphism of genomic RNAs within rotavirus serotypes and subgroups. Arch Virol. 1982;74:65–70. doi: 10.1007/BF01320783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop R F, Unicomb L E, Barnes G L. Epidemiology of rotavirus serotypes in Melbourne, Australia, from 1973 to 1989. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:862–868. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.5.862-868.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Withdrawal of rotavirus vaccine recommendation. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1999;48(43):1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connor M E, Matson D O, Estes M K. Rotavirus vaccines and vaccination potential. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;185:285–337. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78256-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook S M, Glass R I, LeBaron C W, Ho M S. Global seasonality of rotavirus infections. Bull W H O. 1990;68:171–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulson B S, Gentsch J R, Das B K, Bhan M K, Glass R I. Comparison of enzyme immunoassay and reverse transcriptase PCR for identification of serotype G9 rotaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3187–3193. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3187-3193.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cryan B, Lynch M, Whyte D. Rotavirus in Ireland. Eurosurveillance. 1997;2:15–16. doi: 10.2807/esm.02.02.00182-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunliffe N A, Gondwe J, Broadhead R L, Molyneux M E, Woods P A, Bresee J S, Glass R I, Gentsch J R, Hart C A. Rotavirus G and P types in children with acute diarrhea in Blantyre, Malawi, from 1997 to 1998. J Med Virol. 1999;57:308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das B K, Gentsch J R, Cicirello H G, Woods P A, Gupta A, Ramachandran M, Kumar R, Bhan M K, Glass R I. Characterization of rotavirus strains from newborns in New Delhi, India. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1820–1822. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1820-1822.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gault E, Chikhi-Brachet R, Delon S, Schnepf N, Albiges L, Grimprel E, Girardet J-P, Begue P, Garbarg-Chenon A. Distribution of human rotavirus G types circulating in Paris, France, during the 1997–1998 epidemic: high prevalence of type G4. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2373–2375. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2373-2375.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gentsch J R, Glass R I, Woods P, Gouvea V, Gorziglia M, Flores J, Das B K, Bhan M K. Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1365-1373.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gentsch J R, Woods P A, Ramachandran M, Das B K, Leite J P, Alfrieri A, Kumar R, Bhan M K, Glass R I. Review of G and P typing results from a global collection of rotavirus strains: implications for vaccine development. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(Suppl. 1):S30–S36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_1.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerna G A, Scraisisi A, Zenhlin L, DiMatteo A, Mirando P, Parea A, Battaglia M, Milanese G. Isolation in Europe of 69M-like (serotype 8) human rotavirus strains with either subgroup I or II specificity and a long RNA electropherotype. Arch Virol. 1990;112:27–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01348983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gouvea V, Glass R I, Woods P, Taniguchi K, Clark H F, Forrester B, Fang Z Y. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.276-282.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gouvea V, Santos N, Ttimenetsky M D C. Identification of bovine and porcine rotavirus G types by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1338–1340. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1338-1340.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gusmao R H, Mascarenhas J D P, Gabbay Y B, Iins-Lainson Z, Ramos F L P, Monteiro T A F, Valente S A, Fagundes-Neto U, Linhares A C. Rotavirus subgroups, G serotypes and electropherotypes in cases of nosocomial infantile diarrhoea in Belem, Brazil. J Trop Pediatr. 1999;45:81–86. doi: 10.1093/tropej/45.2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa A, Inouye S, Matsuno S, Yamaoka K, Eko R, Suharyono W. Isolation of human rotavirus with a distinct RNA electrophoretic pattern from Indonesia. Microbiol Immunol. 1984;6:719–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1984.tb00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herring A J, Inglis N F, Ojeh C K, Snodgrass D R, Menzies J D. Rapid diagnosis of rotavirus infection by direct detection of viral nucleic acid in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:473–477. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.3.473-477.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoshino Y, Kapikian A Z. Classification of rotavirus VP4 and VP7 serotypes. Arch Virol. 1996;12:99–111. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine. New vaccine development: establishing priorities. Diseases of importance in developing countries. II. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1986. Prospects for immunizing against rotavirus; pp. 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalica A R, Wyatt R G, Kapikian A Z. Detection of differences among human and animal rotaviruses, using analysis of viral RNA. J Am Vet Med. 1978;173:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapikian A Z, Flores J, Vesikari T, Ruuska T, Madore H P, Green K Y, Gorziglia M, Hoshino Y, Chanock R M, Midthun K, Perez-Schael I. Recent advance in development of a rotavirus vaccine for prevention of severe diarrhoeal illness of infants and young children. In: Mestecky J, et al., editors. Immunology of milk and the neonate. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapikian A Z, Chanock R M. Rotaviruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, et al., editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1657–1708. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Legrottaglie R, Volpe A, Rizzi V, Agrimpi P. Isolation and identification of rotaviruses as aetiological agents of neonatal diarrhoea in kids. Electrophoretic characterisation by PAGE. Microbiologica. 1993;16:227–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leite J P G, Alfieri A A, Woods P A, Glass R I, Gentsch J R. Rotavirus G and P types circulating in Brazil: characterisation by RT-PCR, probe hybridisation and sequence analysis. Arch Virol. 1996;141:2365–2374. doi: 10.1007/BF01718637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lourenco M H, Nicolas J C, Cohen J, Scherrer R, Bricout F. Study of human rotavirus genome by electrophoresis: attempt of classification among strains isolated in France. Ann Virol. 1981;132:161–173. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masendycz P J, Palombo E A, Gorrell R J, Bishop R F. Comparison of enzyme immunoassay, PCR and type-specific cDNA probe techniques for identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3104–3108. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3104-3108.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maunula L, von Bonsdorff C-H. Short sequences define genetic lineages: phylogenetic analysis of group A rotaviruses based on partial sequences of genome segments 4 and 9. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:321–332. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-2-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohshima A, Takagi T, Nakagomi T, Matsuno S, Nakagomi O. Molecular characterisation by RNA-RNA hybridisation of a serotype 8 human rotavirus with “super-short” RNA electropherotype. J Med Virol. 1990;30:107–112. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890300206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Mahony J, Foley B, Morgan S, Morgan J G, Hill C. VP4 and VP7 genotyping of rotavirus samples recovered from infected children in Ireland over a 3-year period. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1699–1703. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1699-1703.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palombo E A, Clark R, Bishop R F. Characterisation of a “European-like” serotype G8 human rotavirus isolated in Australia. J Med Virol. 2000;60:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palombo E A, Masendycz P J, Bugg H C, Bogdanovic-Sakran N, Branes G L, Bishop R F. Emergence of G9 in Australia. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1305–1306. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1305-1306.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramachandran M, Das B K, Vij A, Kumar R, Bhambal S S, Kesari N, Rawat H, Bahl L, Thakur S, Woods P A, Glass R I, Bhan M K, Gentsch J R. Unusual diversity of human rotavirus G and P genotypes in India. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:436–439. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.436-439.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramachandran M, Gentsch J R, Parashar U D, Jin S, Woods P A, Holmes J L, Kirkwood C D, Bishop R F, Greenberg H B, Urasawa S, Gerna G, Coulson B S, Taniguchi K, Bresee J S, Glass R I The National Rotavirus Strain Surveillance System Collaborating Laboratories. Detection and characterisation of novel rotavirus strains on the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3223–3229. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3223-3229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramig R F. Genetics of the rotavirus. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:225–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramig R F, Ward R L. Genomic segment reassortment in rotaviruses and other reoviridae. Adv Virus Res. 1999;39:163–207. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60795-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez W J, Kim H W, Brandt C D, Gardner M K, Parrott R H. Use of electrophoresis of RNA from human rotavirus to establish the identity of strains involved in outbreaks in a tertiary care nursery. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:34–40. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan M J, Ramsay M, Brown D. Hospital admissions attributable to rotavirus infection in England and Wales. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(Suppl. 1):S12–S18. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_1.s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanders R C. Molecular epidemiology of human rotavirus infections. Eur J Epidemiol. 1985;1:19–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00162308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos N, Lima R C C, Pereira C F A, Gouvea V. Detection of rotavirus types G8 and G10 among Brazilian children with diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2727–2729. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2727-2729.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sethi K, Olive D M, Strannegard O O, Al-Nakib W. Molecular epidemiology of human rotavirus infections based on genome segment variations in viral strains. J Med Virol. 1988;26:249–259. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890260305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steele A D, Parker S P, Peenze I, Pager C T, Taylor M B, Cubitt W D. Comparative studies of human rotavirus serotype G8 strains recovered in South Africa and the United Kingdom. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:3029–3034. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-11-3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Pongsuwanna Y, Choonthanom M, Jayavasu C, Urasawa S. Molecular and antigenic analyses of serotypes 8 and 10 of bovine rotavirus in Thailand. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2929–2937. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-12-2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tucker A W, Haddix A C, Bresee J S, Holman R C, Parashar U D, Glass R I. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a rotavirus immunisation program for the United States. JAMA. 1998;279:1371–1376. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Unicomb L E, Podder G, Gentsch J R, Woods P A, Hasan K Z, Faruque A S G, Albert M J, Glass R I. Evidence of high-frequency genomic reassortment of group A rotavirus strains in Bangladesh: emergence of type G9 in 1995. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1885–1891. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1885-1891.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woods, P. A., J. R. Gentsch, V. Gouvea, L. Mata, A. Simhon, M. Santosham, Z. Bai, S. Urasawa, and R. I. Glass. Distribution of serotypes of human rotavirus in different populations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:781–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Wu H, Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Urasawa S. Serological and genomic characterisation of human rotaviruses detected in China. J Med Virol. 1998;55:168–176. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199806)55:2<168::aid-jmv14>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]