INTRODUCTION

Cognitive decline negatively affects quality of life and increases morbidity and mortality risk.1 It is the third most expensive condition treated in the USA.1 In 2015, the US Department of Health and Human Services, in the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease, called for “expanding data collection and surveillance efforts” to track the prevalence and impact of cognitive decline.1 Memory loss/problems are “one of the first warning signs of cognitive decline,”1 and tracking their prevalence may be an efficient method for monitoring population-level trends and racial/ethnic disparities in cognitive health.2

The immigrant paradox suggests that racial/ethnic minorities, including immigrant Latinos, are “protected” from negative health outcomes, like cognitive decline, vs. US-born and/or more acculturated Latinos.3 However, eight waves from the Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly recently showed that older age at migration (i.e., less acculturated) was associated with higher risk for cognitive decline.4 Other studies suggest that the effects of acculturation on health are different for Latinos like Mexicans, compared to other Latino ethnic groups in the USA.3 This paper examines the association between an established acculturation scale and self-reported memory problems over time, in a nationally representative sample of Mexican and other Latino adults in the USA.

METHODS

These analyses included 5037 NHANES participants ≥ 45 years, in four 4-year time periods, between 1999 and 2014, who reported their race/ethnicity as Latino/Hispanic and further categorized themselves as “Mexican” or “Other Latino.” The methods are previously described in an NHANES study of the prevalence of US memory problems by race/ethnicity and age category for 20,585 participants ≥ 45 years during 1999–2014.5 The outcome for this analysis was the response to the question: “Are you limited in any way because of difficulty remembering or because you experienced periods of confusion?” (yes/no). A “yes” response was defined “self-reported memory problems.” A previously validated acculturation score used in prior NHANES studies (0/lowest–3/highest), was calculated by giving 1 point for these characteristics: being born in the USA, speaking predominantly English, and living in the USA for ≥ 20 years.6 We used generalized linear regression models with appropriate link functions (e.g., logit for binary, identity for continuous) and appropriate sample weights accounting for unequal probabilities of selection, oversampling, and non-response to examine acculturation, and its association with memory problems, across ethnicity and age groups. Regression models included Latino subgroup (Mexican vs. Other Latino), acculturation score (0 to 3), time period: 1999–2002, 2003–2006, 2007–2010, and 2011–2014, and a two-way acculturation-by-time interaction. These were adjusted for gender, education, and income to poverty ratio (IPR), and conducted for each age group (middle-aged: 45–64 years and older adults: age ≥ 65 years).

RESULTS

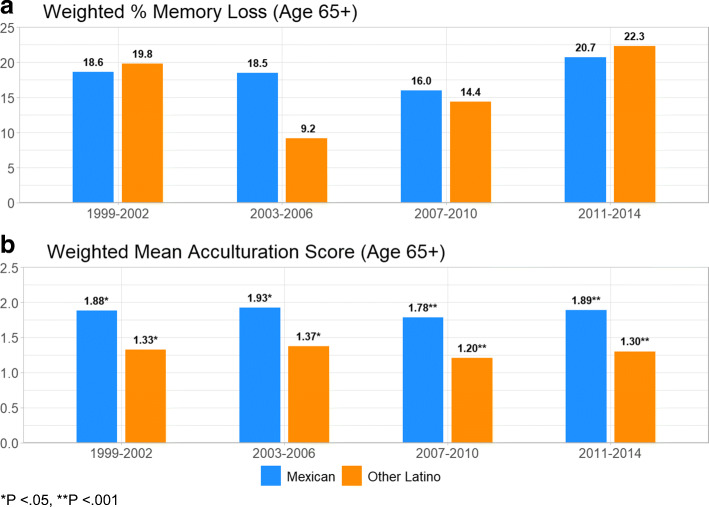

There was no difference in the percentage of unadjusted memory problems between the two ethnic groups for both middle-aged and older respondents. Acculturation scores were higher for the Mexican respondents for both age groups, across all time periods. Figure 1 a and b demonstrate the percentage of unadjusted memory loss problems and mean acculturation scores among older adults. Of note, in this older group, adjusted regressions showed that a higher level of acculturation was associated with reduced odds of experiencing memory problems (Table 1), but was not significant across all time periods. The negative association between self-reported memory problems and acculturation score was observed for all older participants, but only statistically significant for Mexicans in 2011–2014, and for other Latinos in 2007–2010, associations were attenuated after adjustment for covariates, though the trend remained. This pattern was not observed among middle-aged respondents.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted, weighted percentage of memory loss problems and mean acculturation scores for Mexican and Other Latino ethnic subgroups, 65 years and older. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Adjusted Associations Between Memory Loss Problems and Acculturation in Older Respondents, Across Latino Ethnic Subgroups

| Age 65+ | Overall | Mexican | Other Latino | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | *AOR (95% CI) | P | *AOR (95% CI) | P | *AOR (95% CI) | P |

| 1999–2002 | 0.89 (0.72, 1.09) | 0.258 | 0.86 (0.65, 1.14) | 0.297 | 0.82 (0.60, 1.13) | 0.231 |

| 2003–2006 | 0.74 (0.49, 1.12) | 0.161 | 0.72 (0.52, 1.00) | 0.053 | 0.44 (0.15, 1.33) | 0.149 |

| 2007–2010 | 0.82 (0.64, 1.04) | 0.107 | 0.93 (0.64, 1.35) | 0.706 | 0.58 (0.39, 0.86) | 0.008 |

| 2011–2014 | 0.60 (0.46, 0.77) | < 0.001 | 0.46 (0.29, 0.71) | < 0.001 | 0.80 (0.52, 1.22) | 0.303 |

*AOR adjusted odds ratio

Bold signifies that p-value is less than or equal to 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Higher acculturation scores were associated with lower odds of reporting memory problems among older Mexicans and Other Latinos in the USA. This finding is counter to the immigrant paradox, which posits that acculturation is linked to poorer health outcomes. One such example is US Latino immigrants and their US-born children being at a greater risk for diabetes than their racial/ethnic counterparts in the home country—and also at greater risk for diabetes than the average US population. 6 Acculturation effects are likely related to factors like education, socioeconomic status, and other social determinants, and warrant detailed investigation. Regardless, these results point to a need for more aggressive efforts to identify and address cognitive decline among older Latinos, especially the less acculturated.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.National Plan to address Alzheimer’s Disease. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-plan-address-alzheimers-disease-2015-update. .

- 2.MMWR. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Self-Reported Increased Confusion or Memory Loss and Associated Functional Difficulties Among Adults Aged>60 years- 21 states, 2011. [PubMed]

- 3.Weden MM, Miles JNV, Friedman E, et al. The Hispanic paradox: race/ethnicity and nativity, immigrant enclave residence and cognitive impairment among older US adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1085–1091. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downer B, Garcia MA, Saenz J, Markides KS, Wong R. The Role of Education in the Relationship Between Age of Migration to the United States and Risk of Cognitive Impairment Among Older Mexican Americans. Res Aging. 2018;40:411–31. doi: 10.1177/0164027517701447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casillas A, Liang LJ, Vassar S, Brown A. Trends in Memory Problems and Race/Ethnicity in the National Health and Examination Survey, 1999-2014. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(3):525–34. doi: 10.18865/ed.29.3.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien MJ, Alos VA, Davey A, Bueno A, Whitaker RC. Acculturation and the prevalence of diabetes in US Latino Adults, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E176. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]