Abstract

While clinicians are often aware that their patients seek second opinions, they are rarely taught specific skills for how to effectively communicate with patients when they are the ones providing that second opinion. The nuances of these skills are amplified when the second opinion being provided is to the ubiquitous (and often anonymous) Dr. Google. In this perspective, the authors share an approach for discussing a patient’s pre-visit health-related internet findings. After emphasizing the importance of setting the stage, they describe the WWW Framework which proposes “waiting” before responding with data, getting to the “what” of the patient’s search, and “working together” to negotiate a plan. This stepwise approach is designed to provide psychological safety, build a therapeutic alliance, and empower collaborative treatment planning.

Recognizing that effective communication with patients is an essential skill, training programs are increasingly aiming to equip physicians with tools to approach common scenarios such as sharing difficult news,1,2 communicating with minimal jargon,3 or dealing with angry patients.4 Yet there is a frequent communication challenge that is rarely included in these discussions: How can we best address the fact that our patients have often turned to the internet to answer their medical questions before visiting us? In this perspective, we propose a framework for discussing our patients’ health-related internet findings. Our approach is specifically designed to nurture psychological safety, build trust and therapeutic alliance, and allow for collaboratively developing management plans.

While patients have always sought second opinions—either formally from another clinician, or informally from family, books, or other media—the internet has placed a nearly infinite variety of anonymous medical advice a click away. While some of this information is of high quality, the online propagation of misinformation about health has been dubbed an infodemic. This misinformation can be dangerous at times, scaring people away from lifesaving vaccines or pandemic-inhibiting masks, and clinicians are called to be part of the solution.5 Yet despite the facts that nearly all patients endorse searching for medical information online, their searches may increase their anxiety. While many express a desire for guidance from their doctors on identifying appropriate websites, very few patients say they actually discuss what they find with their doctors.6–11 The elephant in the room—our patients’ pre-visit internet health searches—is often invisible, and it is our job to bring it into the open and approach our patients’ findings with grace and skill.

SETTING THE STAGE

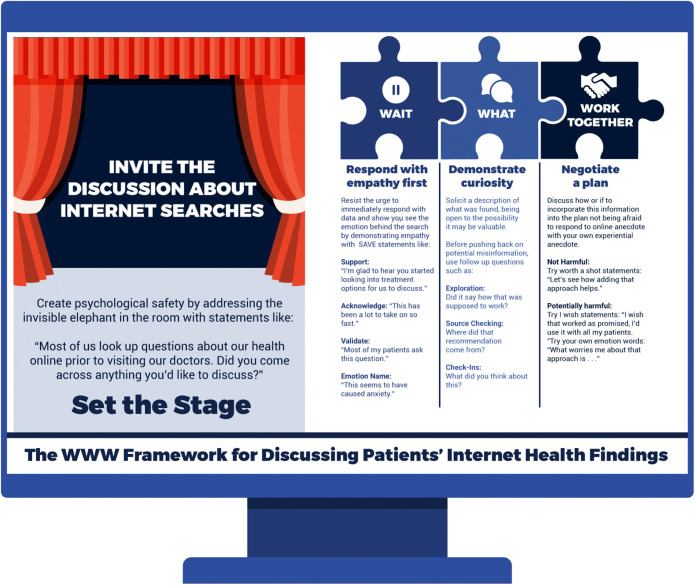

“Most of us look up questions about our health online prior to visiting our doctors. Did you come across anything you’d like to discuss?”

Rather than waiting for our patients (or their families) to volunteer their internet health questions, we should proactively normalize the expectation with a statement such as the one above. Not only does this validate that this behavior is expected (even pointing out that we as clinicians do the same thing); it underscores that it does not offend or undermine your doctor-patient relationship to discuss their findings. This establishes psychological safety for our patients to bring forth their concerns without fear of feeling judged.

While creating the space for our patients to discuss their internet-based questions is essential, the way we respond to these questions is where the most important communication skills come into play. We propose a stepwise approach for these responses, the WWW Framework (Fig. 1), which employs the evidence-based modifiable skills of empathy, curiosity, and collaboration.

Fig. 1.

The WWW Framework

THE WWW FRAMEWORK

Wait—Respond with Empathy First

Overcoming the natural response of defensiveness can be challenging when faced with a patient’s internet-based questions. It can be tempting to flex our perceived intellectual superiority and immediately respond with a data-driven answer. Yet as we learn more about the therapeutic role of choosing to demonstrate empathy with our patients, it is becoming increasingly clear that our patients need more than data to heal.12 If our patient asks about an alternative to chemotherapy they found online, even if we have concerns about the efficacy or safety of the alternative, our first response should be to demonstrate empathy, not to say “unfortunately, that won’t work.” By preparing ourselves to wait before we immediately respond with data, and to consider the emotions behind the patient’s search (in this case anxiety, uncertainty, fear), we can be equipped to respond appropriately.

In their model of relationship-centered communication, Windover and colleagues share a framework (SAVE) for verbally demonstrating empathy through phrases that show Support, Acknowledge the sentiment or challenge, Validate the feeling or question, or explicitly name the Emotion behind it.13 The figure includes examples of such phrases for use in the context of our patients sharing their questions from an internet search. By adding some of these to our toolkit, we can be better prepared to resist the immediate need to respond with data until we have first demonstrated that we understand the emotions behind the search.

What—Demonstrate Curiosity

An important part of creating space for these discussions to occur is allowing our patients the opportunity to tell us what they have found. By entering this portion of the discussion with genuine curiosity, we first allow ourselves to be open to the possibility that what they have found could be accurate and valuable. While much of the concern surrounding internet findings about health focuses on misinformation,5 given the flattening of the access to medical information, patients can often find information that can be helpful, such as uncommon side effect of a medication or a rare diagnosis we may not have considered. Actively choosing curiosity and humility as we explore their findings can allow for a partnering in the patient’s health that may have been missed otherwise. Second, in the case where the findings do seem to genuinely represent misinformation, curiosity remains a powerful tool. When we ask questions such as “did they say how this approach would work?” or “where did that recommendation come from?” patients may begin to critically evaluate their own findings, setting up the possibility for a more fruitful negotiation in the next step.

Work Together—Negotiate a Plan if Necessary

After we have demonstrated empathy and heard what was found, we can begin to work with the patient to devise a plan. If the findings are not controversial and are easily addressed, a further plan may not be needed. However, it is helpful to be prepared with communication tools for the spectrum of possible responses that may be required (see Fig. 1). When an internet-fueled idea is not evidence-based but is also not harmful, being prepared with a “worth a shot” response can help maintain the partnership necessary for a therapeutic alliance. Additionally, “I wish” statements such as “I wish there were something that worked that well, I’d use it in all my patients,” can be helpful when the finding is particularly dubious.

For internet suggestions that are likely to be harmful, we should not be afraid to fight story with story. The sources for many internet health claims are anecdotes on discussion forums (“I tried X and it cured my Y”) where personal stories provide the evidence. We should not avoid using this powerful tool to dispel myths (e.g., “I have had patients who have tried that and they…”). One of the keys to addressing vaccine hesitancy, for example, is to move beyond simply sharing data, and instead use the same storytelling techniques employed to disseminate the misinformation.14 Another helpful approach is simply to share our worry. Framing a response with our own emotion can leverage our relationship and concern for the patient. Saying, “What worries me about trying that is…” is very different than simply stating “Studies have shown….”

By reorienting ourselves to the default position that our patients will have turned to the internet with questions about their health before they visit us, and explicitly inviting them to discuss what they found, we constructively take ownership of our second opinion status. If we proactively equip ourselves with a framework for how to respond with finesse and skill, we can firmly establish the trust needed to make our opinion count.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10964998. . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Carroll C, Carroll C, Goloff N, Pitt MB. When Bad News Isn’t Necessarily Bad: Recognizing Provider Bias when Sharing Unexpected News. Pediatrics. 2018;142(1):e20180503. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitt MB, Hendrickson MA. Eradicating Jargon-Oblivion—a Proposed Classification System of Medical Jargon. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1861–1864. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05526-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delacruz N, Reed S, Splinter A, et al. Take the HEAT: A Pilot Study on Improving Communication with Angry Families. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(6). doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Zarocostas J. How to Fight an Infodemic. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10225). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kubb C, Foran HM. Online Health Information Seeking by Parents for Their Children: Systematic Review and Agenda for Further Research. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8). doi:10.2196/19985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Davis JK. Dr. Google and Premature Consent: Patients Who Trust the Internet More Than They Trust Their Provider. HEC Forum. 2018;30(3). doi:10.1007/s10730-017-9338-z [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Stukus DR. How Dr Google Is Impacting Parental Medical Decision Making. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2019;39(4). doi:10.1016/j.iac.2019.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Van Riel N, Auwerx K, Debbaut P, Van Hees S, Schoenmakers B. The effect of Dr Google on Doctor-Patient Encounters in Primary Care: a Quantitative, Observational, Cross-Sectional Study. BJGP Open. 2017;1(2). doi:10.3399/bjgpopen17X100833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Cacciamani GE, Dell’ Oglio P, Cocci A, et al. Asking “Dr. Google” for a Second Opinion: the Devil Is in the Details. Eur Urol Focus. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2019.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kłak A, Gawińska E, Samoliński B, Raciborski F. Dr Google as the Source of Health Information – the Results of Pilot Qualitative Study. Polish Ann Med. 2017;24(2). doi:10.1016/j.poamed.2017.02.002

- 12.Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):76–84. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X660814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Windover AK, Boissy A, Rice TW, Gilligan T, Velez VJ, Merlino J. The REDE Model of Healthcare Communication: Optimizing Relationship as a Therapeutic Agent. J patient Exp. 2014;1(1):8–13. doi: 10.1177/237437431400100103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shelby A, Ernst K. Story and Science: How Providers and Parents Can Utilize Storytelling to Combat Anti-vaccine Misinformation. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2013;9(8). doi:10.4161/hv.24828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]