Abstract

Background

Atogepant is an oral, small-molecule, calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist for the preventive treatment of migraine.

Methods

In the double-blind, phase 3 ADVANCE trial, participants with 4–14 migraine days/month were randomized to atogepant 10 mg, 30 mg, 60 mg, or placebo once daily for 12 weeks. We evaluated the time course of efficacy of atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine. Analyses included change from baseline in mean monthly migraine days during each of the three 4-week treatment periods, change in weekly migraine days during weeks 1–4, and proportion of participants with a migraine on each day during the first week.

Results

We analyzed 873 participants (n = 214 atogepant 10 mg, n = 223 atogepant 30 mg, n = 222 atogepant 60 mg, n = 214 placebo). For weeks 1–4, mean change from baseline in mean monthly migraine days ranged from −3.1 to −3.9 across atogepant doses vs −1.6 for placebo (p < 0.0001). For weeks 5–8 and 9–12, reductions in mean monthly migraine days ranged from −3.7 to −4.2 for atogepant vs −2.9 for placebo (p ≤ 0.012) and −4.2 to −4.4 for atogepant vs −3.0 for placebo (p < 0.0002), respectively. Mean change from baseline in weekly migraine days in week 1 ranged from −0.77 to −1.03 for atogepant vs −0.29 with placebo (p < 0.0001). Percentages of participants reporting a migraine on post-dose day 1 ranged from 10.8% to 14.1% for atogepant vs 25.2% with placebo (p ≤ 0.0071).

Conclusion

Atogepant demonstrated treatment benefits as early as the first full day after treatment initiation, and sustained efficacy across each 4-week interval during the 12-week treatment period.

Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03777059

Keywords: Atogepant, calcitonin gene–related peptide, time course, efficacy

Introduction

Migraine attacks can be severe, incapacitating, and have a substantial impact on an individual’s life (1,2). The goals of preventive treatment for migraine include reducing the frequency, intensity, and duration of attacks, as well as improving functional ability and quality of life (3–5). However, many people with migraine discontinue or repeatedly cycle through preventive treatment options due to suboptimal efficacy or concerns regarding the safety and tolerability of currently available oral preventive medications (5–7).

In studies that evaluated individual preferences for the treatment of migraine, participants ranked efficacy, speed of onset, and an oral formulation among the most important attributes when choosing a preventive medication (8–10). However, some current oral preventive drugs require administration for several weeks or months before therapeutic benefit occurs, with many individuals still failing to achieve sufficient efficacy (11,12). When efficacy is not reached after a certain treatment duration, or a medication has been titrated to the ceiling dose but is no longer effective or tolerated, it is recommended to re-evaluate and possibly discontinue treatment (4,5). Considering the significant impact of migraine on an individual’s life both during and between attacks, there is a need for treatments that reliably address preventive treatment goals and provide a rapid onset of action.

Calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) is a potent vasodilator and inflammatory mediator known to play an important role in migraine pathophysiology (13). CGRP levels increase during attacks, and CGRP concentrations can be elevated between attacks in people with high frequency or chronic migraine (14). Furthermore, an infusion of CGRP has been shown to trigger migraine-like attacks in people who have migraine with or without aura (15–17). Blocking CGRP, either the neuropeptide or its receptor, is effective for the preventive treatment of migraine (18,19). Atogepant is an oral, small-molecule, CGRP receptor antagonist (gepant) in development for the preventive treatment of migraine (20). The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of once-daily atogepant was demonstrated in a phase 2/3 dose-ranging trial (20), the phase 3 ADVANCE trial (21), and a 52-week, open-label, long-term safety (LTS) trial (22).

In the phase 3 ADVANCE trial, atogepant showed significant efficacy for the preventive treatment of migraine versus placebo (21). Once-daily atogepant was associated with a significant decrease in the primary efficacy endpoint of mean monthly migraine days (MMDs) assessed across the full 3 months of double-blind treatment (21); however, the time course of efficacy, including onset and persistence of effects, have not yet been reported. The objective of this analysis of ADVANCE trial data was to evaluate the onset, magnitude, and persistence of benefit of atogepant compared with placebo for the preventive treatment of migraine.

Methods

Study design

Trial methods have been previously published (21). The ADVANCE trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trial (NCT03777059) conducted at 136 sites in the United States from 14 December 2018 through 19 June 2020. Participants were randomized (1:1:1:1) to atogepant 10, 30, or 60 mg, or placebo administered once daily for 12 weeks. Randomization was stratified based on prior exposure (yes/no) to a migraine preventive medication with proven efficacy. This stratum was included in the statistical model as a categorical fixed effect. The trial consisted of a screening visit, a 4-week eDiary baseline period, a 12-week double-blind treatment period, and a 4-week safety follow-up period for a total duration of 20 weeks. Atogepant tablets and matching placebo were provided in identical blister cards to maintain blinding. Participants were instructed to take study treatment once a day at approximately the same time each day. The first dose of study treatment was taken at the clinic. The study protocols were reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board for each site. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice principles and the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Participants provided written informed consent prior to trial enrollment.

Participants

The trial included adults 18–80 years of age (inclusive), with at least a 1-year history of migraine with or without aura consistent with a diagnosis according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) (23), age of migraine onset <50 years, and 4–14 migraine days per month on average in the 3 months prior to visit 1 and during the 28-day baseline period, as per eDiary. Exclusion criteria included a current diagnosis of chronic migraine, new daily persistent headache, cluster headache, or painful cranial neuropathy as defined by ICHD-3, and 15 or more headache days per month on average across the 3 months before visit 1 or during the baseline period. Participants were also excluded if they had inadequate response to more than 4 medications (2 of which have different mechanisms of action) prescribed for the preventive treatment of migraine, and use of opioids or barbiturates more than 2 days per month, triptans or ergots 10 or more days per month, or simple analgesics (eg, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], acetaminophen) 15 or more days per month in the 3 months prior to visit 1 or during the 28-day baseline period. Use of barbiturates was also excluded 30 days prior to screening and throughout the trial.

Outcome measures

The primary endpoint in the ADVANCE trial was the change from baseline in mean MMDs across the 12-week treatment period. The exploratory efficacy outcomes for this analysis included change from baseline in MMDs during each of the 4-week periods of the double-blind treatment period, change from baseline in weekly migraine days during the first month (weeks 1–4), and the proportion of participants with a migraine on each day during the first week of treatment. Additional efficacy endpoints included the change from baseline in the following: monthly moderate/severe headache days, mean headache days by month, monthly acute medication use days by month, and monthly cumulative headache hours by month. The definitions of a migraine day and a headache day used in this trial are in Table S1. Participants used an eDiary daily at home to collect data on headache duration, characteristics, and symptoms, and acute medication use, which were collectively applied to define migraine days and headache days.

Participants received their first dose of study medication during the clinic visit on day 1 (randomization visit). A migraine day was defined as any calendar day on which a headache occurred that met the criteria in Table S1 (calendar days began at midnight and lasted until 11:59 PM [23:59]). When determining the proportion of participants that experienced a migraine day during the first week following the first dose of study medication, the day after initial administration was considered to be day 1 (referred to as post-dose day 1), and was the earliest clinically relevant timepoint to assess efficacy. This decision was made considering that the timing of study medication administration depended on the participant’s scheduled visit and could have included a substantial portion of the day prior to administering the study medication in which a headache may have occurred.

Adverse events (AEs) were reported throughout the 12-week treatment period and for an additional 4-week follow-up period. Safety parameters included clinical laboratory evaluations, vital signs, electrocardiograms (ECGs), and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

Statistical methods

All efficacy analyses were performed using the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population, consisting of all randomized participants who received at least 1 dose of study treatment, had an evaluable baseline period of eDiary data, and had at least 1 evaluable postbaseline 4-week period of eDiary data during the treatment period (weeks 1–4, 5–8, and 9–12). A month was defined as each 4-week treatment interval (28 days). For monthly data, baseline MMDs were calculated during the 28-day baseline period prior to treatment initiation. A minimum of 20 days of completed eDiary data during the 28-day baseline period was required for migraine days to be evaluable. For participants with fewer than 28 days of baseline data, the number of migraine days was prorated to a 28-day equivalent. After treatment initiation, the months with 14 or more days of completed eDiary data were prorated to 28-day equivalent figures. The months with fewer than 14 days of data entry were considered missing. The same method of deriving MMDs was used to derive monthly moderate/severe headache days, monthly headache days, and monthly cumulative headache hours.

For weekly migraine day data, baseline was defined as baseline MMDs over 4 weeks divided by 4 to compute the 1-week average. After treatment initiation, weekly migraine days were calculated for consecutive 7-day periods beginning with day 1. Weeks with 4 to 7 days of eDiary data were prorated to 7-day equivalent figures. Weeks with fewer than 4 days of headache data were considered missing. The daily proportion of participants in the mITT population experiencing migraine was summarized from the initial treatment day to 6 full days after treatment. For the baseline percentage of participants with a migraine day, the average of MMDs during the baseline period for the mITT population was divided by 28.

The comparison between each atogepant dose with placebo for the continuous endpoints was conducted using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) of the change from baseline. The statistical model included treatment group, visit, prior exposure (yes/no) to a migraine prevention medication with proven efficacy, and treatment group-by-visit interaction as categorical fixed effects. The model also included the baseline score and baseline-by-visit interaction as covariates. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to model the covariance of within-participant repeated measurements. For repeated measures using MMRM, the model parameters were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood estimation incorporating all observed data, assuming data are missing at random (MAR). Pairwise contrasts in the MMRM model were used to make the pairwise comparisons of each atogepant dose to placebo. Least squares (LS) means and differences in LS means were used to estimate the effects of treatment and comparisons between treatments, as well as standard error (SE), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the P value that corresponded to the between-treatment group difference.

The daily proportion of participants experiencing migraine was analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model assuming a binary distribution for the response and a logit link function. The analysis model included the model terms as previously described in the MMRM model above. The unstructured covariance matrix was used to account for the correlation among repeated measurements. The treatment difference in terms of odds ratio between each atogepant dose group and placebo was estimated and tested from this model. All statistical tests reported in this analysis were conducted 2-sided at an alpha level of 0.05 without adjusting for multiplicity.

Results

Participants

A total of 910 participants were randomized to treatment with placebo (n = 223), atogepant 10 mg (n = 222), atogepant 30 mg (n = 230), or atogepant 60 mg (n = 235). Overall, 88.5% of participants (805/910) completed the double-blind treatment period. The mITT population included 873 participants: placebo, n = 214; atogepant 10 mg, n = 214; atogepant 30 mg, n = 223; atogepant 60 mg, n = 222. The most common reasons for discontinuation were withdrawal by participant (3.8% [35/910]), AEs (2.7% [25/910]), and protocol deviations (2.6% [24/910]). Baseline characteristics were generally similar between treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics (safety population).

| Baseline Characteristics | Placebo (n = 222) | Atogepant 10 mg QD (n = 221) | Atogepant30 mg QD (n = 228) | Atogepant 60 mg QD (n = 231) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 40.3 (12.8) | 41.4 (12.1) | 42.1 (11.7) | 42.5 (12.4) |

| Female, n (%) | 198 (89.2) | 200 (90.5) | 204 (89.5) | 199 (86.1) |

| White, n (%) | 194 (87.4) | 181 (81.9) | 185 (81.1) | 192 (83.1) |

| Non-Hispanic, n (%) | 199 (89.6) | 200 (90.5) | 209 (91.7) | 217 (93.9) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 30.8 (8.7) | 30.4 (7.6) | 31.2 (7.6) | 29.9 (7.3) |

BMI, body mass index; QD, once daily; SD, standard deviation.

Efficacy outcomes by month (4-week treatment periods)

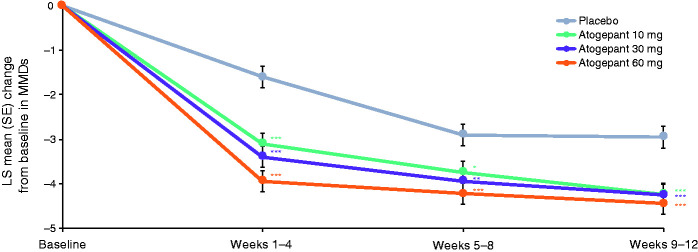

The mean MMDs at baseline in the mITT population ranged from 7.5–7.9 across treatment groups (Table 2). During the first treatment period (weeks 1–4), LS mean change from baseline in MMDs was −3.1 for atogepant 10 mg, −3.4 for atogepant 30 mg, −3.9 for atogepant 60 mg, and −1.6 for placebo (P<0.0001 for all atogepant groups) (Figure 1). This greater decrease in MMDs with atogepant compared with placebo was maintained during the second 4-week treatment period (weeks 5–8: −3.7 for atogepant 10 mg, −3.9 for atogepant 30 mg, −4.2 for atogepant 60 mg, and −2.9 for placebo; P ≤ 0.012 for all atogepant groups) and the third 4-week treatment period (weeks 9–12: −4.2 for atogepant 10 mg, −4.3 for atogepant 30 mg, −4.4 for atogepant 60 mg, and −3.0 for placebo; P < 0.0002 for all atogepant groups).

Table 2.

Baseline parameters on efficacy measures (mITT population).

| Baseline Parameters, mean (SD) | Placebo (n = 214) | Atogepant 10 mg QD (n = 214) | Atogepant 30 mg QD (n = 223) | Atogepant 60 mg QD (n = 222) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly migraine days | 7.5 (2.4) | 7.5 (2.5) | 7.9 (2.3) | 7.8 (2.3) |

| Monthly headache days | 8.4 (2.6) | 8.4 (2.8) | 8.8 (2.6) | 9.0 (2.6) |

| Monthly cumulative headache hours | 51.1 (34.5) | 47.4 (27.3) | 49.5 (26.7) | 50.4 (27.4) |

| Monthly acute medication use days | 6.5 (3.2) | 6.6 (3.0) | 6.7 (3.0) | 6.9 (3.2) |

| Monthly moderate/severe headache days | 6.5 (2.6) | 6.4 (2.6) | 6.9 (2.5) | 6.9 (2.6) |

| Weekly migraine days* | 1.9 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.6) | 2.0 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.6) |

mITT, modified intent-to-treat; QD, once daily; SD, standard deviation.

*For weekly data, baseline was defined as monthly migraine days divided by 4, and change from baseline in weekly migraine days was to be calculated for consecutive 7-day periods beginning with day 1.

Figure 1.

Change from baseline monthly migraine days during the treatment period (mITT population).*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. LS, least squares; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; MMD, monthly migraine day; SE, standard error.

A similar result was observed for the outcomes of both moderate/severe headache days (Figure S1) and mean headache days (Figure S2) throughout each of the three 4-week treatment periods. The LS mean change from baseline in moderate/severe headache days in the first treatment period (weeks 1–4) was −3.0 for atogepant 10 mg, −3.2 for atogepant 30 mg, −3.8 for atogepant 60 mg, and −1.7 for placebo (P<0.0001 for all atogepant groups). The LS mean change from baseline in mean headache days in the first treatment period was −3.2 for atogepant 10 mg, −3.4 for atogepant 30 mg, −3.8 for atogepant 60 mg, and −1.4 for placebo (P ≤ 0.0001 for all atogepant groups).

The mean monthly acute medication use days at baseline ranged from 6.5 to 6.9 across treatment groups. The LS mean change from baseline in acute medication use days during the first treatment period was −3.3 for atogepant 10 mg, −3.4 for atogepant 30 mg, −3.7 for atogepant 60 mg, and −1.7 for placebo (P<0.0001 for all atogepant groups). The LS mean change in acute medication use days showed a nominally significant difference from placebo starting at the first treatment period and persisting in the second and third treatment periods (Figure S3). Baseline mean cumulative headache hours ranged from 47.4–51.1 in the mITT population. The LS mean reduction from baseline in mean cumulative headache hours during the first treatment period was −23.3 for atogepant 10 mg, −23.6 for atogepant 30 mg, −25.1 for atogepant 60 mg, and −9.5 for placebo (P < 0.0001 for all atogepant groups) (Figure S4).

Efficacy outcomes by week in the first month

At baseline, mean weekly migraine days ranged from 1.9–2.0 across treatment groups. During the first week of treatment, LS mean change from baseline in weekly migraine days was −0.8 in the atogepant 10 mg group, −0.9 for atogepant 30 mg, −1.0 for atogepant 60 mg, and −0.3 for placebo (P < 0.0001 for all atogepant groups) (Figure 2). The significant reduction in weekly migraine days with atogepant compared with placebo extended into the second week of treatment, where the LS means were −0.7 for atogepant 10 mg, −0.7 for atogepant 30 mg, −1.0 for atogepant 60 mg, and −0.4 for placebo (P ≤ 0.0397 for all atogepant groups). For week 3, the LS means were −0.8 for atogepant 10 mg, −0.9 for atogepant 30 mg, −1.0 for atogepant 60 mg, and −0.4 for placebo (P ≤ 0.0013 for all atogepant groups). Similarly, in week 4, the LS means were −0.8 for atogepant 10 mg, −0.9 for atogepant 30 mg, −1.0 for atogepant 60 mg, and −0.5 for placebo (P ≤ 0.0071 for all atogepant groups).

Figure 2.

Change from baseline in weekly migraine days during the first month of treatment (mITT population).*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. LS, least squares; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; SE, standard error.

Efficacy outcomes by day in the first week

The proportions of participants who reported a migraine day on any given day during the baseline period was derived from the baseline MMDs divided by 28 and ranged from 26.6%–28.1% across treatment groups. On post-dose day 1, the proportion of participants who reported a migraine day was 14.1% for atogepant 10 mg, 10.8% for atogepant 30 mg, and 12.3% for atogepant 60 mg vs 25.2% in the placebo group (P ≤ 0.0071 for all atogepant groups) (Figure 3). On post-dose days 2–6, the proportion of participants reporting a migraine was consistently lower across the 3 atogepant treatment groups compared with placebo, with the majority of days reaching significance vs placebo (P < 0.05) in the atogepant 30 mg and 60 mg dose groups. The days when the difference between atogepant and placebo did not reach significance were day 3, day 4, and day 6 for atogepant 10 mg and day 4 for atogepant 60 mg. On post-dose day 1, the odds ratio vs placebo for reporting a migraine was 0.49 with atogepant 10 mg, 0.33 with atogepant 30 mg, and 0.39 with atogepant 60 mg.

Figure 3.

Proportion of participants with a migraine each day during the first week of treatmenta (mITT population). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. mITT, modified intent-to-treat. aDay 0 excluded, as migraine attacks occurring prior to study drug administration were included.

Safety

Once-daily oral atogepant was safe and well tolerated throughout the trial. The percentage of participants reporting treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was similar among all groups, ranging from 52.2%– 53.7% across the atogepant treatment groups compared with 56.8% in the placebo group. AEs leading to discontinuation ranged from 1.8%–4.1% in the atogepant groups compared with 2.7% in the placebo group. No dose-response relationship was observed for AEs leading to discontinuation, and no deaths occurred. Results and a description of the AEs from the safety population have been previously reported (21).

Discussion

In this analysis of efficacy data from the ADVANCE trial of atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine, all 3 doses of once-daily atogepant showed a significant reduction in mean MMDs compared with placebo during the first month (4-week period) of treatment. The benefits of atogepant were evident as early as the first full day after treatment administration; on that day, 25.2% of placebo-treated participants reported a migraine in comparison with 10.8%–14.1% of participants treated with various atogepant doses. All doses of atogepant continued to show significant reductions in weekly migraine days in each of the first 4 weeks of treatment and in MMDs during the first 4 weeks, weeks 5–8, and weeks 9–12. Collectively, these results support that atogepant has a rapid onset of efficacy and the improvement in MMDs is maintained across the 3 months of treatment.

The primary outcome of the ADVANCE trial was change from baseline in mean MMDs measured across all 3 months of treatment. The trial demonstrated the efficacy of atogepant in the preventive treatment of migraine (21). Atogepant has also been shown to be associated with clinically meaningful benefits vs placebo in measures of quality of life and daily functioning as early as the first month of treatment (24,25). The present results expand on the findings from the pivotal trial and provide clinically relevant details on daily, weekly, and monthly treatment effects, all of which are important to fully characterize the time course of atogepant efficacy.

Studies of CGRP-targeted monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for preventive treatment in participants with episodic migraine have also demonstrated the rapid efficacy of this drug class. Galcanezumab demonstrated a significant reduction in the proportion of participants reporting a migraine day beginning on the first day after the initial injection (26). Similarly, with fremanezumab, significant reductions compared with placebo in migraine days were observed as early as the second study day (first full day following injection) (27). With eptinezumab, the percentage of participants with a migraine was reduced on day 1 after the first dose compared with placebo (28). The benefit of treatment with erenumab vs placebo reached significance on day 3 after the higher dose (140 mg) was administered, and on day 7 after the lower dose (70 mg) (29). Across these studies, the percentages of placebo participants who reported a migraine day on post-dose day 1 ranged from 22.5% to 27%, which is consistent with our results showing 25.2% of participants randomized to placebo on post-dose day 1. Although additional studies are needed, the rapid onset of action seen with preventive treatments targeting CGRP may be due to overlapping mechanisms of action with acute medications that also target CGRP, such as ubrogepant and rimegepant (30,31). Together with the current results, these data support that CGRP-targeted therapies, regardless of route of administration, provide rapid onset of efficacy in the preventive treatment of migraine.

The choice of a preventive medication is highly individualized and some people may prefer an orally administered medication (6,32). In addition to providing a less-invasive route of administration, gepants have a shorter half-life compared with mAbs (hours versus weeks). This may be preferable in cases where women are trying to become pregnant and would want to immediately halt preventive treatment, or when side effects are intolerable and there is a need to immediately reduce plasma concentrations of the medication (32).

Additional studies are also needed to characterize the dose-response relationship of atogepant and determine whether there are greater benefits with the higher atogepant doses. The ADVANCE trial was limited to participants with fewer than 15 migraine days per month and, therefore, the results may vary in individuals with chronic migraine. As the treatment period in this trial was limited to 12 weeks, the long-term efficacy of atogepant could not be evaluated. Also, due to the treatment duration, any potential changes in magnitude of treatment effect beyond 3 months with atogepant could not be fully evaluated. One strength of the analysis was that follow-up time began as early as day 1 after the initial dose, which allowed for the characterization of the early benefits of atogepant treatment. Additionally, the first dose of study medication was administered in clinic. This ensured that day 1 efficacy reflects accurate dosing from the previous day.

Conclusions

Atogepant provided an early and sustained reduction in migraine days. Efficacy was evident as early as the first day following treatment initiation, when the proportion of participants with migraine was lower with treatment than with placebo. In addition, statistically significant reductions were seen in each week during the first month of treatment, and in each month of the 3-month double-blind treatment period.

Key Findings

Once-daily oral atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine provided a rapid onset of action, with a statistically significant decrease in the likelihood of experiencing a migraine attack as early as the first full day after administration.

All doses of atogepant were associated with a statistically significant reduction in weekly migraine days across the first week of treatment and each subsequent week within the first month of treatment.

All doses of atogepant were associated with a statistically significant reduction in monthly migraine days in each month (4-week interval) of the 3-month double-blind treatment period.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cep-10.1177_03331024211042385 for Time course of efficacy of atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine: Results from the randomized, double-blind ADVANCE trial by Todd J Schwedt, Richard B Lipton, Jessica Ailani, Stephen D Silberstein, Cristina Tassorelli, Hua Guo, Kaifeng Lu, Brett Dabruzzo, Rosa Miceli, Lawrence Severt, Michelle Finnegan and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Cory Hussar of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, Parsippany, NJ, and was funded by AbbVie. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors. The authors received no honorarium/fee or other form of financial support related to the development of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Todd J Schwedt serves on the Board of Directors for the American Headache Society and the International Headache Society. He has received research support from the American Migraine Foundation, Amgen, Henry Jackson Foundation, National Institutes of Health, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and US Department of Defense. Within the past 12 months, he has received personal compensation for serving as a consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie/Allergan, Biohaven, Eli Lilly, Equinox, Lundbeck, and Novartis. He has received royalties from UpToDate. He holds stock options in Aural Analytics and Nocira.

Richard B Lipton has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, the FDA, and the National Headache Foundation. He serves as consultant, advisory board member, or has received honoraria or research support from AbbVie/Allergan, Amgen, Biohaven, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories (Promius), electroCore, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Lundbeck, Merck, Novartis, Teva, Vector, and Vedanta Research. He receives royalties from Wolff’s Headache, 8th edition (Oxford University Press, 2009), and Informa. He holds stock/options in Biohaven and Ctrl M.

Jessica Ailani has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Axsome, Ctrl M, Eli Lilly and Company, Lundbeck, Impel, Satsuma, Theranica, Teva, and Vorso; has served as a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly and Company, Lundbeck, and Teva; has received honoraria from Medscape; and has provided editorial services to Current Pain and Headache Reports, NeurologyLive, and SELF magazine. Her institute has received clinical trial support from AbbVie, the American Migraine Foundation, Biohaven, Eli Lilly and Company, Satsuma, and Zosano.

Stephen D Silberstein is a consultant and/or advisory panel member for and has received honoraria from AbbVie, Alder Biopharmaceuticals, Amgen, Avanir, eNeura, electroCore Medical, Labrys Biologics, Medscape, Medtronic, Neuralieve, NINDS, Pfizer, and Teva. His employer receives research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Cumberland Pharmaceuticals, electroCore Medical, Labrys Biologics, Eli Lilly, Mars, and Troy Healthcare.

Cristina Tassorelli has participated in advisory boards for AbbVie, electroCore, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. She has lectured at symposia sponsored by AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Teva. She is principal investigator or collaborator in clinical trials sponsored by Alder, Eli Lilly, IBSA, Novartis, and Teva. She has received research grants from the European Commission, the Italian Ministry of Health, the Italian Ministry of University, the Migraine Research Foundation, and the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Foundation.

Hua Guo, Kaifeng Lu, Brett Dabruzzo, Rosa Miceli, Lawrence Severt, Michelle Finnegan and Joel M Trugman are employees of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was sponsored by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie).

Ethics or institutional review board approval: The protocols for the ADVANCE trial were reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board for each site. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice principles and the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to trial enrollment.

ORCID iDs: Stephen D Silberstein https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9467-5567

Cristina Tassorelli https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1513-2113

Data availability statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

References

- 1.Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML, et al. Life with migraine: Effects on relationships, career, and finances from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache 2019; 59: 1286–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 2007; 68: 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodick DW, Silberstein SD. Migraine prevention. Pract Neurol 2007; 7: 383–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silberstein SD. Preventive migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2015; 21: 973–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Headache Society. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 2019; 59: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second international burden of migraine study (IBMS-II). Headache 2013; 53: 644–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF. Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm 2014; 20: 22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallagher RM, Kunkel R. Migraine medication attributes important for patient compliance: concerns about side effects may delay treatment. Headache 2003; 43: 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitsikostas DD, Belesioti I, Arvaniti C, et al. Patients' preferences for headache acute and preventive treatment. J Headache Pain 2017; 18: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peres MF, Silberstein S, Moreira F, et al. Patients' preference for migraine preventive therapy. Headache 2007; 47: 540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garza I, Swanson JW. Prophylaxis of migraine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2006; 2: 281–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delussi M, Vecchio E, Libro G, et al. Failure of preventive treatments in migraine: an observational retrospective study in a tertiary headache center. BMC Neurol 2020; 20: 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, et al. Pathophysiology of migraine: a disorder of sensory processing. Physiol Rev 2017; 97: 553–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durham PL. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and migraine. Headache 2006; 46: S3–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo S, Vollesen ALH, Olesen J, et al. Premonitory and nonheadache symptoms induced by CGRP and PACAP38 in patients with migraine. Pain 2016; 157: 2773–2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lassen LH, Haderslev PA, Jacobsen VB, et al. CGRP may play a causative role in migraine. Cephalalgia 2002; 22: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen JM, Hauge AW, Olesen J, et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide triggers migraine-like attacks in patients with migraine with aura. Cephalalgia 2010; 30: 1179–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charles A. The pathophysiology of migraine: implications for clinical management. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17: 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodick DW. CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: Evidence review and clinical implications. Cephalalgia 2019; 39: 445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally administered atogepant for the prevention of episodic migraine in adults: a double-blind, randomised phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Neurol 2020; 19: 727–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ailani J, Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, et al. Atogepant significantly reduces mean monthly migraine days in the phase 3 trial (ADVANCE) for the prevention of migraine [abstract MTV20-OR-018]. Cephalalgia 2020; 40: 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashina M, Tepper S, Reuter U, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of atogepant 60 mg following once daily dosing over 1 year for the preventive treatment of migraine [abstract 2664]. Neurology 2021; 96: 2664. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipton RB, Pozo-Rosich P, Blumenfeld AM, et al. Atogepant improved patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures of activity impairment in migraine-diary and headache impact test in a 12-week, double-blind, randomized phase 3 (ADVANCE) trial for preventive treatment of migraine [abstract 1454]. Neurology 2021; 96: 1454. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodick DW, Pozo-Rosich P, Blumenfeld AM, et al . Atogepant improved patient-reported migraine-specific quality of life in a 12-week phase 3 (ADVANCE) trial for preventive treatment of migraine [abstract 1459]. Neurology 2021; 96: 1459. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Detke HC, Millen BA, Zhang Q, et al. Rapid onset of effect of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: analysis of the EVOLVE studies. Headache 2020; 60: 348–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winner PK, Spierings ELH, Yeung PP, et al. Early onset of efficacy with fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. Headache 2019; 59: 1743–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodick DW, Gottschalk C, Cady R, et al. Eptinezumab demonstrated efficacy in sustained prevention of episodic and chronic migraine beginning on day 1 after dosing. Headache 2020; 60: 2220–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwedt T, Reuter U, Tepper S, et al. Early onset of efficacy with erenumab in patients with episodic and chronic migraine. J Headache Pain 2018; 19: 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Croop R, Goadsby PJ, Stock DA, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rimegepant orally disintegrating tablet for the acute treatment of migraine: a randomised, phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019; 394: 737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant for the treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 2230–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hargreaves R, Olesen J. Calcitonin gene-related peptide modulators – the history and renaissance of a new migraine drug class. Headache 2019; 59: 951–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cep-10.1177_03331024211042385 for Time course of efficacy of atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine: Results from the randomized, double-blind ADVANCE trial by Todd J Schwedt, Richard B Lipton, Jessica Ailani, Stephen D Silberstein, Cristina Tassorelli, Hua Guo, Kaifeng Lu, Brett Dabruzzo, Rosa Miceli, Lawrence Severt, Michelle Finnegan and Joel M Trugman in Cephalalgia

Data Availability Statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.