Abstract

Forty group B Streptococcus (GBS) isolates obtained from Europe and the United States previously reported to be nontypeable (NT) by capsule serotype determination were subjected to buoyant density gradient centrifugation. From nearly half of the isolates capsule-expressing variants could be selected. For characterization of the remaining NT-GBS isolates, the capsule operon (cps) was amplified by the long-fragment PCR technique and compared by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. The patterns from serotype reference isolates (n = 32) were first determined and used as a comparison matrix for the NT-GBS isolates. Using two restriction enzymes, SduI and AvaII, cluster analysis revealed a high degree of similarity within serotypes but less than 88% similarity between serotypes. However, serotypes III and VII were each split in two distant RFLP clusters, which were designated III1 and III2 and VII1 and VII2, respectively. Among the isolates that remained NT after repeated Percoll gradient selections, two insertional mutants were revealed. Both were found in blood isolates and harbored insertion sequence (IS) elements within cpsD: one harbored IS1548, and the other harbored IS861. All other NT-GBS isolates could, by cluster analysis, be referred to different serotypes by comparison to the RFLP reference matrix. In pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of SmaI-restricted chromosomal DNA, patterns from allelic type 1 and 2 isolates were essentially distributed in separate clusters in serotypes III and VII. A covariation with insertion sequence IS1548 in the hylB gene was suggested for serotype III, since allelic type III1 harboring IS1548 in hylB, clustered separately. The variation in serotype VII was not dependent on the presence of IS1548, which was not detected at any position in the type VII chromosome.

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) is the most common cause of neonatal bacteremia and meningitis but can also cause serious infectious disease among adults (3, 6, 28). However, commensal intestinal or genital colonization is probably the most common manifestation of contact between GBS and humans (3, 5). Apart from pregnancy, several predisposing host factors important for the pathogenesis of invasive GBS infection in adults have been proposed, such as advanced age and chronic debilitating disease (6, 15). Individual bacterial virulence factors have been identified, and the clonal dispersal of GBS with increased virulence has been suggested as a factor in neonatal disease (12, 25, 29, 36).

Clinical isolates of GBS generally have a polysaccharide capsule, which is the basis for the serotyping traditionally used for epidemiological purposes. Nine immunologically distinct serotypes have so far been described: serotypes Ia, Ib, and II through VIII (16, 18, 19, 35, 37, 38). Research, e.g., for developing vaccines, has focused on serotype III, since it has been the serotype most commonly isolated in invasive neonatal disease (3). While type III together with serotypes Ia, Ib, and II remains important, the most dramatic change in prevalence during the last decade has been the increase in type V among invasive isolates (4, 11, 14). Evidently, GBS serotype prevalence fluctuates over time and also with geographical location. In Japan, the most common serotypes are VI and VIII, while reports of those serotypes from the rest of the world are rare (22). Furthermore, the relative distribution of serotypes III and V differs among isolates from laboratories representing different areas of the United States (24).

The polysaccharide capsule is a major virulence factor in GBS, and consequently most invasive GBS isolates are typeable and hence encapsulated. However, nontypeable GBSs (NT-GBSs) are infrequently reported as a cause of invasive infection and may be an increasing problem in adult invasive GBS infection (11). We have previously described an inverse relationship between the capsule thickness and the buoyant density (9). Clinical GBS isolates have often proved to be heterogeneous, and subpopulations with thick or thin capsules may arise in a phase shift-like manner (32). Reversible NT-GBS phase variants have previously been encountered in blood isolates at our laboratory, where enrichment of low-density subpopulations with hypotonic Percoll gradient centrifugation before typing has been successful (33).

Apart from technical reasons, we hypothesize three causes for a GBS isolate to be nontypeable: (i) the isolate is a reversible nonencapsulated phase variant, (ii) the isolate produces an uncharacterized polysaccharide for which antibodies not yet are available (i.e., a new serotype), and (iii) the isolate has an insertion or a mutation in genes essential for capsule expression. The aim of this study was to develop methods to classify NT-GBSs and hopefully find the etiology explaining the loss of capsule expression. To that end, GBS isolates previously reported to be NT, gathered from well-known typing laboratories in Scandinavia and the United States, were analyzed to reveal phase variants, supported by a newly devised method of restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. This RFLP method also revealed major subdivision of serotypes III and VII, so the study was extended to compare the impact of allelic variation on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns for the two serotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Clinical GBS isolates from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and the United States that were previously reported as NT were collected (6, 10, 13, 21). Together with additional isolates from our own laboratory, a total of 40 isolates from adults and neonates (20 invasive and 20 noninvasive isolates) were gathered (Table 1). Reference type strains for each of serotypes I through VIII were kindly supplied by J. Motlova at the Czech National Collection of Type Cultures (CNCTC) in Prague, Czechoslovakia. GBS blood isolates from our laboratory were added to make up three isolates of each of serotypes Ia, Ib, II, IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII. For serotype III, a total of six isolates were investigated; for serotype VII, five isolates were investigated (Table 2). Bacteria were plated on blood agar plates (Columbia II agar base [BBL, Cockeysville, Md.] supplemented with 5% horse blood) or in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) and incubated overnight at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Results of serotyping after hypotonic Percoll gradient centrifugation and after cps cluster typing of NT-GBS isolates

| Isolate | Characteristic

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of isolate origina | Source of isolateb | Patient agec | Serotype after centrifugation | cps cluster or allelic typed | |

| T15/94 | No | B | A | V | NDe |

| T24/95 | No | B | A | II | ND |

| T35/95 | No | B | A | II | ND |

| 5531 | S | B | A | III | III1 |

| T58/95 | No | B | N | IIIf | III2 |

| UM6270 | S | B | N | III | III1 |

| GA1558 | U | B | A | V | ND |

| GA2797 | U | B | A | V | ND |

| Ros1034 | S | B | A | Ia | ND |

| T159525/93 | No | C | A | IIf | ND |

| T159923/93 | No | C | A | IIf | ND |

| T163704/93 | No | C | A | IIf | ND |

| T16975/93 | No | C | A | IIf | ND |

| 3102 | D | C | A | Ia | ND |

| 3129 | D | C | A | III | III2 |

| 3131 | D | C | A | V | ND |

| 3139 | D | C | A | II | ND |

| T37/94 | No | C | N | Ia | ND |

| T45/94 | No | C | N | III | III1 |

| GA4116 | U | B | A | Ib | ND |

| SH3953 | S | C | A | Ia | ND |

| GA1718 | U | B | N | NT | Ia |

| 954 | D | C | N | NT | Ia |

| SH120 | S | C | A | NT | Ia |

| SH3531 | S | C | A | NT | Ia |

| SH127 | S | C | A | NT | Ib |

| SH378 | S | C | A | NT | Ib |

| SH754 | S | C | A | NT | II |

| T24/97 | No | B | A | NT | III1 |

| Ros724 | S | B | A | NT | III1 |

| SH995 | S | C | A | NT | III1 |

| Ros106 | S | B | A | NT | IS1548 in cpsD |

| GA4096 | U | B | A | NT | IS861 in cpsD |

| T1/98 | No | B | A | NT | V |

| GA1613 | U | B | A | NT | V |

| GA1687 | U | B | N | NT | V |

| GA2613 | U | B | A | NT | V |

| GA4075 | U | B | A | NT | V |

| 3124 | D | C | A | NT | VI |

| 3126 | D | C | A | NT | VI |

D, Denmark; No, Norway; S, Sweden; U, United States.

B, blood isolate; C, colonizing isolate.

A, adult; N, neonatal.

Allelic type denoted by subscript.

ND, not determined.

Typeable at our laboratory before hypotonic Percoll gradient centrifugation.

TABLE 2.

Type reference strains

| Serotype and allelic typea | Strain designation |

|---|---|

| Ia | CNCTC index 58/59 |

| Ia | B88-4568 |

| Ia | B91-5963 |

| Ib | CNCTC 59/59 |

| Ib | B89-1803 |

| Ib | B95-4854 |

| II | CNCTC 60/59 |

| II | B88-543 |

| II | B93-6268 |

| III1 | CNCTC 4/70 |

| III1 | B4877 |

| III1 | B90-261 |

| III2 | B88-1975 |

| III2 | M732 |

| III2 | B90-1259 |

| IV | CNCTC 1/82 |

| IV | B95-2516 |

| IV | CNCTC B114877 |

| V | CNCTC 10/84 |

| V | B96-2781 |

| V | B97-360 |

| VI | CNCTC 2/86 |

| VI | J-B114862 |

| VI | J-B114852 |

| VII1 | CNCTC 4/89 |

| VII1 | S2-03104 |

| VII1 | B132157/r |

| VII2 | B123348 |

| VII2 | B124055 |

| VIII | CNCTC 1/92 |

| VIII | 130609 |

| VIII | CNCTC 130669 |

Index denotes allelic type, determined as a result of this study.

Serotyping.

Serotyping was performed by coagglutination as previously described, with a kit for serotypes I through VIII (10).

Hypotonic Percoll gradient centrifugation.

Gradient centrifugation was used to estimate the buoyant density of GBS isolates and to select populations of lower buoyant density, as previously described (32). If an NT-GBS isolate turned reactive in serotyping assays, it was considered a “reverting” NT-GBS isolate. If an isolate remained NT during three cultivation and centrifugation cycles, it was considered a “nonreverting” NT-GBS isolate.

Sialic acid analysis.

All GBS capsule polysaccharides known so far contain sialic acid; therefore, sialic acid analysis can be used for interstrain comparisons of capsule polysaccharide levels. The pellet from a 15-ml culture of GBS (optical density at 500 nm = 1.0) was used to extract sialic acid by HCl hydrolysis (0.1 N HCl at 84°C for 20 min). Analysis was performed with N-acetylneuraminic acid (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) as the standard, with the thiobarbituric acid method modified from that of Skoza and Mohos (34). Protein analysis was performed with the hydrolysate by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce, Boule AB, Huddinge, Sweden). All analyses were made in duplicate. To compare means, Student's t test was used.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA.

GBS isolates were grown overnight at 37°C in 15 ml of Todd-Hewitt yeast broth supplemented with 20 mM threonine. Bacteria were washed once and resuspended in 5 ml of 0.02 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) with 1 M NaCl and 0.05% Triton X-100. One hundred microliters of mutanolysin (5 IU/μl) (Sigma) was added, and the sample was incubated overnight at 4°C. Two sequential incubations at 37°C for 15 min each were done, with 100 μl of RNase (10 mg/ml) and 100 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml), respectively. Three subsequent extraction steps were performed with volumes equal to the buffer-DNA solution: (i) with redistilled phenol and chloroform in a 50/50 mixture, (ii) with chloroform, and (iii) with isobutanol. DNA was precipitated by the addition of a 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 4.8) and 2 volumes of cold 95% ethanol and incubation for 30 min at −70°C, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min. The precipitated DNA was washed twice in cold 70% ethanol, dried, and then resuspended in 0.5 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) with 1 mM EDTA.

Capsule gene cluster RFLP analysis.

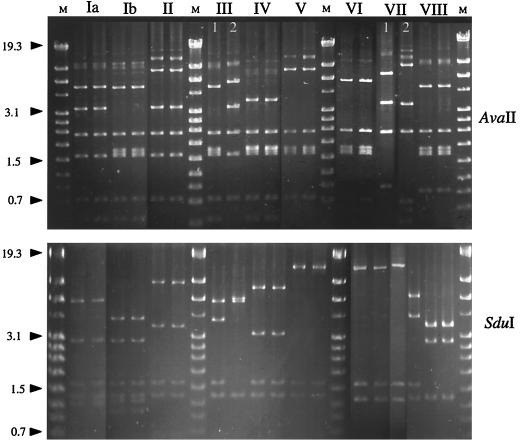

A total of 19 nonreverting and 32 typeable GBS isolates were investigated (3 for each serotype or allelic type except for allelic type VII2, where only 2 isolates were retrieved). Long-fragment PCRs were set up with the Boehringer Mannheim Expand Long Fragment PCR kit (Roche Diagnostics Scandinavia AB, Bromma, Sweden) with 3 to 400 μM of each primer, lorfXfo (5′-CAAGGAGGCGATAACGATAG AGGTAGAAATCAAG-3′) and loEFrev (5′-TTTGACCCTG ATCGCGCAGGAATAATAC-3′) and 350 μM dinucleoside triphosphates in buffer 1 with a final concentration of 1.75 mM MgCl2 with 2.6 U of enzyme mixture in a reaction mixture volume of 50 μl. As a template, 2 to 5 μl of chromosomal DNA prepared as above was used. Thermocycling was performed on a PTC-200 thermocycler (MJ Research, Falkenberg, Sweden) at 92°C for 2 min for 1 cycle, followed by 92°C for 20 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 6 min for 10 cycles, followed by 92°C for 10 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 6 min extended by 20 s for each cycle for a total of 20 cycles, followed by 68°C for 7 min. Separate digestions with AvaII and SduI (MBI; Tamrolab AB, Molndal, Sweden) of the long-fragment PCR amplicons were performed, and fragments were separated on 0.8% agarose gels. Molecular weight standard IV (Roche) was included at multiple positions on the gel to allow optimal normalization between runs in the subsequent conversion to computer format prior to cluster analysis (see Fig. 2).

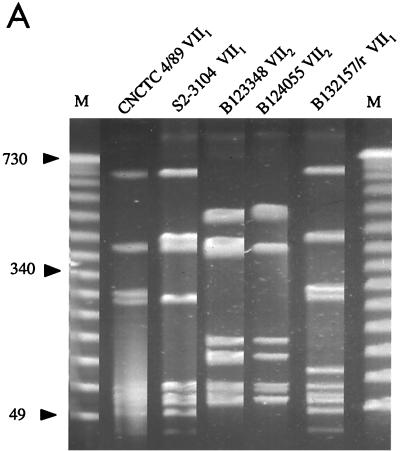

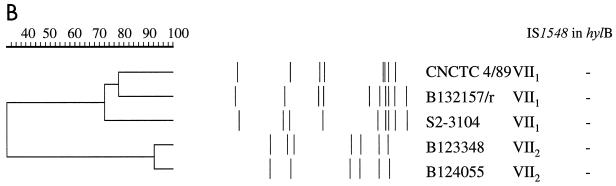

FIG. 2.

RFLP analyses of long-fragment PCR amplicons from the cps capsule gene cluster from two reference type strains each for every GBS serotype. Allelic variants for serotypes III and VII are designated 1 and 2. M, molecular weight standard in kilobases.

PFGE.

The serotypes displaying allelic variation in the cps cluster RFLP analysis, namely serotypes III and VII, were analyzed by PFGE. In all, 14 type III sensu lato (s.l.), reference, reverting NT-GBS, and cluster type III strains were included in a PFGE comparison. The seven serotype VII strains in the study were analyzed on a separate PFGE gel.

Chromosomal DNA from GBS isolates embedded in agarose plugs was prepared as previously described (7, 8). An agarose slice was incubated overnight at 30°C with 20 U of SmaI (MBI) in the enzyme buffer provided. Plugs were washed in Tris-EDTA buffer for 1 h at 5°C before being mounted into wells of a 1% Pulsed Field Certified Agarose gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories AB, Sundbyberg, Sweden) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (pH 8.3). Electrophoresis was performed on an automated PFGE apparatus, the Gene Path strain typing system (Bio-Rad). The standard program for fragment sizes of 50 to 600 kb was used. A standard λ ladder (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.) was included alongside the samples. The agarose gel was stained with 0.2% ethidium bromide, washed in tap water, visualized, and photographed under UV light.

Cluster analysis.

Restriction profile photographs were analyzed with GelCompar software, version 4.0 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). The scans of the AvaII and SduI restriction gels were combined into one RFLP pattern for each isolate. AvaII bands of less than 0.7 kb were often faint and were not included in the clustering. The unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) clustering method was used, using the Dice coefficient with a band position tolerance of 1 to 1.2%. The electrophoresis patterns of both the capsule gene cluster RFLP and the PFGE of chromosomal DNA were analyzed with the same program settings.

Sequencing technique.

Direct PCR product sequencing was performed with ABI PRISM products (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Stockholm, Sweden) as previously described (20).

PCR mapping.

The area immediately upstream of cpsA and cpsA-D was mapped with PCR primers, using previously published amplification protocols (20). All serotype III and VII isolates were explored for the insertion of IS1548 in the hylB gene by PCR analysis as previously described (8).

RESULTS

Serotyping before and after hypotonic Percoll gradient centrifugation.

Without pretreatment, five of the isolates previously classified as NT-GBS isolates could be typed by coagglutination at our laboratory. After the isolation of phase variants by gradient centrifugation, the serotypes of 16 additional NT-GBS isolates could be determined (Table 1). A total of 19 of 35 NT-GBS isolates were still nontypeable after hypotonic Percoll gradient centrifugation.

Sialic acid and buoyant density estimations.

No NT-GBS isolate with low buoyant density and high levels of sialic acid, suggestive of a new serotype, was found. The nonreverting isolates had significantly (P < 0.05) lower sialic acid levels than reverting isolates, with a mean of 0.7 (standard deviation [SD, 0.3]) to 1.8 (SD, 1.9) μg/mg of protein, respectively. The five typeable NT-GBS isolates did not differ significantly in sialic acid content compared to the reference isolates, with a mean of 3.6 (SD, 1.3) to 2.9 (SD, 1.1) μg/mg of protein. The reference isolates displayed significantly higher amounts of sialic acid than both reverting and nonreverting NT-GBS isolates (P < 0.001).

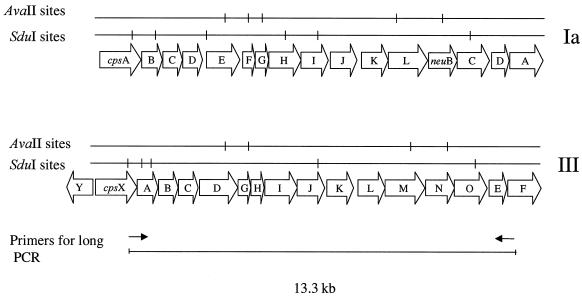

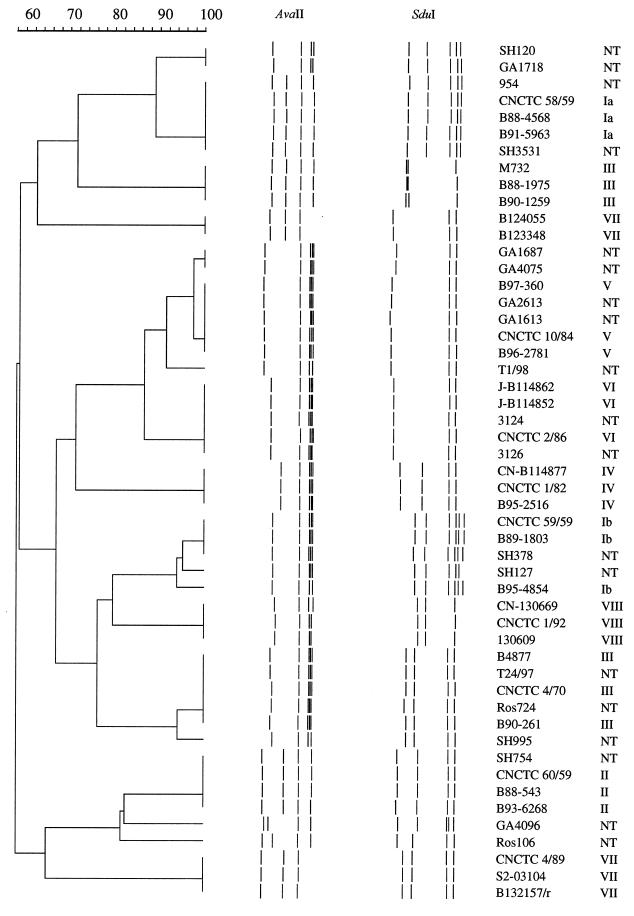

Capsule locus-targeted RFLP.

The cps locus-specific RFLP method was devised not only as an alternative typing method but also to evaluate the gross structure of the capsule gene cluster. Long-fragment PCR generated an approximately 13.3-kb-long amplicon spanning cpsX to cpsE (Fig. 1). By visual inspection of the AvaII restrictions gels, a distinction between serotypes started to appear, but the addition of a parallel SduI restriction gel is needed to allow classification in relation to serotype (Fig. 2). In order to use cluster analysis of the gels for typing purposes, a suitable cutoff value had to be established, i.e., a similarity index above which similar organization of the capsule gene locus is suggested. When only reference isolates were included in the dendrogram, comparison of the combined AvaII and SduI restriction patterns showed the highest percentage of similarity between two separate serotypes, 88%, between serotypes V and VI (data not shown). All other serotypes differed more with similarities of 60 to 80%; therefore, 88% was set as the cutoff value in the comparison when NT-GBS isolates were added to the dendrogram (Fig. 3). All three reference serotype isolates clustered with 100% similarity with the exception of serotype Ib, where a minor diversity (within 90% similarity) was displayed. However, serotypes III and VII were each split in two distant clusters with a similarity of approximately only 60%. When the RFLP of nonreverting NT-GBS isolates was added to the a dendrogram, four main divisions became apparent. The first division contains serotypes Ia, III2, and VII2; the second division contains serotypes V, VI, and IV; the third division contains serotypes Ib, VIII, and III1; and the fourth division contains serotypes II and VII1 (Fig. 3). Of the individual isolates, 17 of 19 clustered with >88% similarity to a reference serotype. In fact, 9 of 19 clustered with 100% similarity, 6 more isolates displayed ≥90% similarity, and 2 isolates clustered close to the cutoff at 89% (Fig. 3). The ascribed cluster types for NT-GBS isolates according to the closest clustering reference serotype in the dendrogram are compiled in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Open reading frames in the GBS capsule gene cluster and positions for long-fragment PCR primers. Positions are based on two entries in the GenBank: for serotype Ia, accession no. AB028896 (39), and for serotype III, accession no. AF163833. Restriction sites for the enzymes used in the RFLP, investigation, AvaII and SduI, are denoted above the genes.

FIG. 3.

Gel-dendrogram diagram of cps long-fragment PCR amplicon RFLP from 19 NT-GBS and 32 typeable GBS isolates. Each isolate is represented by one lane where the schematic band profile is combined from separate digestions with AvaII (left) and SduI (right). The horizontal bar (upper left) represents the percent similarity coefficient. Clustering was performed using the UPGMA method.

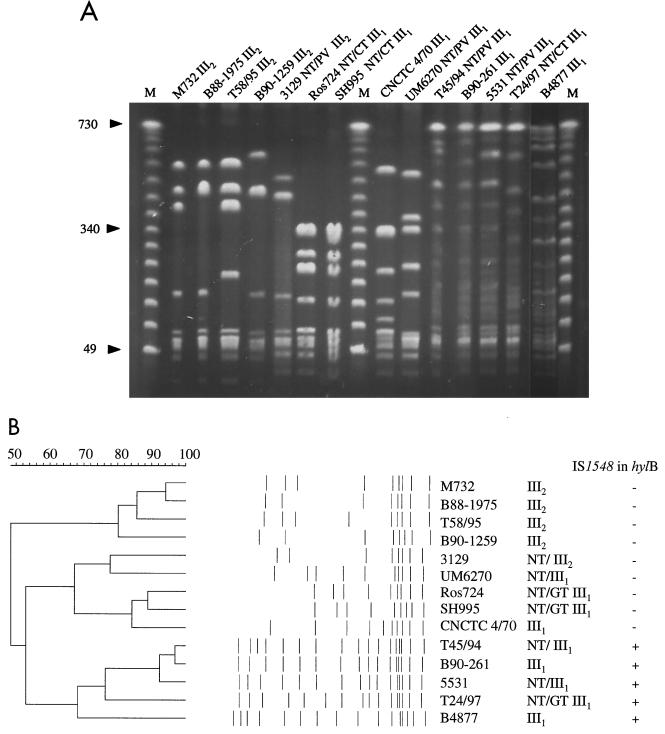

PFGE analysis.

Visual inspection of the type III s.l. PFGE gels secludes one group of III1 isolates that form more scattered patterns with several weak partially digested bands complicating comparison and transformation to computer format preceding cluster analysis (Fig. 4A). In this process, visual guidance and careful scrutiny of negatives or gels are of paramount importance. The PFGE patterns were reproducible, resisting variation in the digestion protocol. The dendrogram analysis matched the visual impression in that three main clusters could be seen: one cluster contained allelic type III2 isolates only, one cluster contained the scattered allelic type III1 pattern that was PCR positive for IS1548 in hylB, and a middle cluster contained IS1548-negative allelic type III1 isolates and one allelic type III2 isolate (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of SmaI-digested chromosomal DNA from GBS serotype III s.l. NT/PV III denotes NT-GBS where phase variant serotype III was found after gradient centrifugation; NT/CT III, nonreverting isolates with cluster type III. III1 and III2, allelic types III1 and III2, respectively, according to cps typing. (A) PFGE gel. M, molecular weight standards in kilobases. (B) Cluster analysis and presence of IS1548 in the hylB gene. The horizontal bar (upper left) represents the percent similarity coefficient. Clustering was performed using UPGMA method.

For the serotype VII isolates, the dendrogram analysis of the gel picture resulted in a split of the two allelic variants into different PFGE clusters, which both lacked IS1548 (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of SmaI-digested chromosomal DNA from GBS serotype VII reference strains. VII1 and VII2, allelic variants. (A) PFGE gel. M, molecular weight standards in kilobases. (B) Cluster analysis and presence of IS1548 in the hylB gene.

PCR mapping.

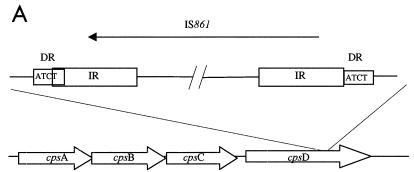

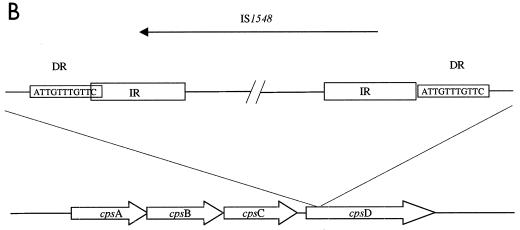

In search of insertions or gross rearrangements, nonreverting NT-GBS isolates were mapped using PCR primers for sequences from cpsY to cpsD (20). Two of 19 nonreverting NT-GBS isolates, Ros106 and GA4096, generated approximately 1.5-kb-larger amplicons with primers for cpsA and cpsD then the other isolates. Nucleotide sequencing of the amplicon flanks revealed the insertion of IS1548 (8) in Ros106 and the insertion of IS861 (30) in GA4096 into cpsD (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Schematic diagram of IS elements in the capsule gene cluster in two NT-GBS blood isolates. (A) Isolate GA4096 harboring IS861 in cpsD. (B) Isolate Ros106 harboring IS1548 in cpsD. The sequences for the direct repeats (DR) at target sites are shown in boxes. The inverted repeat (IR) sequences for the present isolates are noted in open boxes and were identical with sequences previously reported for IS861 (accession no. M22449) (30) and IS1548 (accession no. Y14270) (8). Arrows show directions of transcription for IS elements.

DISCUSSION

Following the classical description in the 1930s by R. Lancefield of GBS serotyping based on immunoprecipitation in gel (23), many additional serotyping techniques have been devised, such as immunodiffusion, coagglutination, or enzyme immunoassays (1, 10, 17, 23). The theoretical detection levels of these techniques differ by 10- to 100-fold (26). Furthermore, different extraction procedures for the antigenic preparations and differences in antisera may also influence the sensitivity of the test and thus the rate of NT-GBS isolates found (27). In this study, more than 10% of GBS isolates previously reported as NT could be ascribed to a serotype merely by applying an alternative method of analysis. The technical reasons discussed above may have contributed to the initial nonreactivity in those cases. In roughly 50% of the NT-GBS isolates gathered for this study, a shift to lower buoyant density after hypotonic Percoll gradient centrifugation accompanied a positive capsule-serotyping reaction (Table 2). It seems that the primary NT reaction may be due to the fact that the NT-GBSs were isolated in a reversible non- or thin-encapsulated phase. All the major serotypes could be detected among the reverting isolates, which implies that the phase variation is a common phenomenon in GBSs regardless of serotype. A variable level of serotype antigen expression has previously also been reported by Palacios et al., where low levels of serotype polysaccharide have been found in subsets of NT-GBS isolates (27).

The RFLP method described here allowed 17 of 19 nonreverting isolates to be assigned a cluster type in relation to serotype reference strains. Thus, a genotyping method compatible with the prevailing serotyping system is proposed. The described genotyping system still needs preparation of chromosomal DNA as a template, and DNA-primer relations for some of the isolates need to be individually optimized to obtain a long-fragment PCR amplicon. The major advantages are that genotyping seems to work where other methods so far have failed with NT-GBS and that allelic variants of type III and VII may be diagnosed. Furthermore, the suggested relations between serotypes within the divisions may be interesting from an evolutionary point of view. Reports on an evolutionary split for serotype III have previously been made based on population genetic approaches (12, 25). The split of the low-prevalence serotype VII into two distinct lineages has to our knowledge not been published before. If allelic variation in the cps locus has any functional implications at all, it remains to be shown; but nevertheless, it has the potential to be a genotypic marker for epidemiological investigations of GBS serotype III and VII infections.

A close similarity of RFLP patterns in NT-GBS isolates and typeable reference strains suggests a similar gross organization of the capsule gene clusters. Although the decreased similarity index seen for NT-GBS isolates in the cps dendrogram as compared to reference isolates (Fig. 3) may conceal causes of defective capsule expression, no definite explanation is offered. However, in two of the nonreverting isolates a rationale was proposed, since insertion sequences (ISs) were identified within the capsule gene cluster (Fig. 6). Both insertions affected cpsD, and loss of the corresponding product, galactosyl transferase, has previously been demonstrated to be detrimental to capsule expression (31). That the search for IS elements is relevant when loss of gene function occurs in wild-type GBS isolates was also exemplified in a previous report by Granlund et al., where inactivation of the hyaluronidase gene by the insertion of IS1548 was described (8). The target sequences for the IS elements in our report differ from those previously published, indicating that variation in the target site is allowed (Fig. 6). Furthermore, short target sequences (as in IS861) increase the probability for multiple insertions in the GBS genome with possible interference with other genes. Up to eight copies of IS861 and IS1548 have previously been reported in serotype III GBS isolates (8, 32), and the overall impact of insertion elements on the phenotype, genome size, and PFGE patterns could consequently be substantial. Although the two isolates which harbored insertion elements, Ros106 and GA4096, had a similarity index below the chosen cutoff value for assigning a cluster type, the closest clustering reference (serotype II) still seems possible. These insertion elements add one or two restriction sites for the enzymes used, which may explain the deviation. No candidate with a putative new serotype was discovered among the NT-GBS isolates. This would have been suggested if a low-density isolate was found with a high level of sialic acid and low similarity to reference strains in the cluster typing.

DNA-based typing methods are important tools in the epidemiology of infectious diseases. Due to high discriminatory power and reproducibility, PFGE has been established as the method of choice for tracking common-source outbreaks of infection (2). Some correspondence to serotype can be seen in cluster analysis following PFGE of GBS genomic DNA (4). Since the cps cluster RFLP described here was designed to be congruent to the existing serotyping scheme, it allows an increased resolution, compared to PFGE, for ascribing a type to NT-GBS isolates. The combination of locus-based and genomic DNA typing methods, together with accessory PCR and phenotyping methods, may be needed to cover all aspects of variability that GBS can display.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A. Kvam, R. Helmig, M. Farley, and I. Julander are gratefully acknowledged for supplying nontypeable GBS isolates. Reference type strains were kindly supplied by J. Motlova at the CNTCC in Prague, Czechoslovakia. M. Wagner kindly supplied type reference strains as well as anti-type VIII antiserum and P. Cleary kindly supplied type reference strains.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council (08675), The Wiberg Foundation, The Swedish Medical Society, The Sven Jerring Foundation, and The Umeå University Insamlings Fonden to M.N.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

After completion of this report, the gene designations in the serotype III cps cluster (GenBank accession no. AF163833) were revised by Chaffin et al. (D. O. Chaffin, S. B. Beres, H. H. Yim, and C. E. Rubens, J. Bacteriol. 182:4466–4477, 2000) and are now congruent to that of serotype Ia (39).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakere G, Flores A E, Ferrieri P, Frasch C E. Inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for serotyping of group B streptococcal isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2564–2567. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2564-2567.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbeit R D. Laboratory procedures for the epidemiologic analysis of microorganisms. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1999. pp. 116–137. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker C J, Edwards M S. Group B streptococcal infections. In: Remington J S, Klein J S, editors. Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1995. pp. 980–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumberg H M, Stephens D S, Modansky M, Erwin M, Elliot J, Facklam R R, Schuchat A, Baughman W, Farley M M. Invasive group B streptococcal disease: the emergence of serotype V. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:365–373. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dillon H C, Jr, Gray E, Pass M A, Gray B M. Anorectal and vaginal carriage of group B streptococci during pregnancy. J Infect Dis. 1982;145:794–799. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.6.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farley M M, Harvey R C, Stull T, Smith J D, Schuchat A, Wenger J D, Stephens D S. A population-based assessment of invasive disease due to group B Streptococcus in nonpregnant adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1807–1811. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306243282503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fasola E, Livdahl C, Ferrieri P. Molecular analysis of multiple isolates of the major serotypes of group B streptococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2616–2620. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2616-2620.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granlund M, Öberg L, Sellin M, Norgren M. Identification of a novel insertion element, IS1548, in group B streptococci, predominantly in strains causing endocarditis. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:967–976. doi: 10.1086/515233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Håkansson S, Granlund-Edstedt M, Sellin M, Holm S E. Demonstration and characterization of buoyant density subpopulations of group B Streptococcus type III. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:741–746. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Håkansson S, Burman L G, Henrichsen J, Holm S E. Novel coagglutination method for serotyping group B streptococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3268–3269. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3268-3269.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison L H, Elliott J A, Dwyer D M, Libonati J P, Ferrieri P, Billmann L, Schuchat A. Serotype distribution of invasive group B streptococcal isolates in Maryland: implications for vaccine formulation. Maryland Emerging Infections Program. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:998–1002. doi: 10.1086/515260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauge M, Jespersgaard C, Poulsen K, Kilian M. Population structure of Streptococcus agalactiae reveals an association between specific evolutionary lineages and putative virulence factors but not disease. Infect Immun. 1996;64:919–925. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.919-925.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helmig R, Uldbjerg N, Boris J, Kilian M. Clonal analysis of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from infants with neonatal sepsis or meningitis and their mothers and from healthy pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:904–909. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hickman M E, Rench M A, Ferrieri P, Baker C J. Changing epidemiology of group B streptococcal colonization. Pediatrics. 1999;104:203–209. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson L A, Hilsdon R, Farley M M, Harrison L H, Reingold A L, Plikaytis B D, Wenger J D, Schuchat A. Risk factors for group B streptococcal disease in adults. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:415–420. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-6-199509150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jennings H J. Capsular polysaccharides as vaccine candidates. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;150:97–127. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74694-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen N E. Production and evaluation of antisera for serological type determination of group-B streptococci by double diffusion in agarose gel. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand B. 1979;87:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1979.tb02407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kogan G, Uhrin D, Brisson J R, Paoletti L C, Blodgett A E, Kasper D L, Jennings H J. Structural and immunochemical characterization of the type VIII group B Streptococcus capsular polysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8786–8790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kogan G, Brisson J R, Kasper D L, von Hunolstein C, Orefici G, Jennings H J. Structural elucidation of the novel type VII group B Streptococcus capsular polysaccharide by high resolution NMR spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res. 1995;277:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(95)00195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koskiniemi S, Sellin M, Norgren M. Identification of two genes, cpsX and cpsY, with putative regulatory function on capsule expression in group B streptococci. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;21:159–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kvam A I, Efstratiou A, Bevanger L, Cookson B D, Marticorena I F, George R C, Maeland J A. Distribution of serovariants of group B streptococci in isolates from England and Norway. Med Microbiol. 1995;42:246–250. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-4-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lachenauer C S, Kasper D L, Shimada J, Ichiman Y, Ohtsuka H, Kaku M, Paoletti L C, Ferrieri P, Madoff L C. Serotypes VI and VIII predominate among group B streptococci isolated from pregnant Japanese women. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1030–1033. doi: 10.1086/314666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lancefield R. A serological differentiation of human and other groups of hemolytic streptococci. J Exp Med. 1933;57:571–595. doi: 10.1084/jem.57.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin F Y, Clemens J D, Azimi P H, Regan J A, Weisman L E, Philips III J B, Rhoads G G, Clark P, Brenner R A, Ferrieri P. Capsular polysaccharide types of group B streptococcal isolates from neonates with early-onset systemic infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:790–792. doi: 10.1086/517810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musser J M, Mattingly S J, Quentin R, Goudeau A, Selander R K. Identification of a high-virulence clone of type III Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus) causing invasive neonatal disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4731–4735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols W S, Nakamura R M. Agglutination and agglutination inhibition assays. In: Rose N R, Friedman H, Fahey J L, editors. Manual of clinical laboratory immunology. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society of Microbiology; 1986. pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palacios G C, Eskew E K, Solorzano F, Mattingly S J. Decreased capacity for type-specific-antigen synthesis accounts for high prevalence of nontypeable strains of group B streptococci in Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2923–2926. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2923-2926.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfaller M A, Jones R N, Marshall S A, Edmond M B, Wenzel R P. Nosocomial streptococcal blood stream infections in the SCOPE program: species occurrence and antimicrobial resistance. The SCOPE Hospital Study Group. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;29:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rolland K, Marois C, Siquier V, Cattier B, Quentin R. Genetic features of Streptococcus agalactiae strains causing severe neonatal infections, as revealed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and hylB gene analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1892–1898. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1892-1898.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubens C E, Heggen L M, Kuypers J M. IS861, a group B streptococcal insertion sequence related to IS150 and IS3 of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5531–5535. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5531-5535.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubens C E, Heggen L M, Haft R F, Wessels M R. Identification of cpsD, a gene essential for type III capsule expression in group B streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:843–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sellin M, Håkansson S, Norgren M. Phase-shift of polysaccharide capsule expression in group B streptococci, type III. Microb Pathog. 1995;18:401–415. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1995.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sellin M, Linderholm M, Norgren M, Håkansson S. Endocarditis caused by a group B Streptococcus strain, type III, in a nonencapsulated phase. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2471–2473. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2471-2473.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skoza L, Mohos S. Stable thiobarbituric acid chromophore with dimethyl sulphoxide. Application to sialic acid assay in analytical de-O-acetylation. Biochem J. 1976;159:457–462. doi: 10.1042/bj1590457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Hunolstein C, D'Ascenzi S, Wagner B, Jelinkova J, Alfarone G, Recchia S, Wagner M, Orefici G. Immunochemistry of capsular type polysaccharide and virulence properties of type VI Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococci) Infect Immun. 1993;61:1272–1280. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1272-1280.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wessels M R, Rubens C E, Benedi V J, Kasper D L. Definition of a bacterial virulence factor: sialylation of the group B streptococcal capsule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8983–8987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wessels M R, DiFabio J L, Benedi V J, Kasper D L, Michon F, Brisson J R, Jelinkova J, Jennings H J. Structural determination and immunochemical characterization of the type V group B Streptococcus capsular polysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6714–6719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wessels M R, Benedi W J, Jennings H J, Michon F, DiFabio J L, Kasper D L. Isolation and characterization of type IV group B Streptococcus capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1089–1094. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1089-1094.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto S, Miyake K, Koike Y, Watanabe M, Machida Y, Ohta M, Iijima S. Molecular characterization of type-specific capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis genes of Streptococcus agalactiae type Ia. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5176–5184. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5176-5184.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]