Abstract

Quantitative PCR-based strategies are typically effective for monitoring BCR-ABL1 transcript levels in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Additionally, some patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors can experience long-term treatment-free remission after discontinuation of the inhibitor. However, this outcome hinges on effectively monitoring the patient's response to therapy. We present a patient with CML and multiple BCR-ABL1 transcripts, including a rare isoform that lacks qPCR standardization. We describe unexpected discrepancies in transcript quantification, further having an impact on clinical decision-making regarding duration of treatment. To better inform clinical practice, we suggest monitoring patients at the same testing facility to better track transcript trend.

Keywords: BCR-ABL transcript, Minimal residual disease, Chronic myeloid leukemia, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a myeloproliferative neoplasm caused by t(9;22) chromosomal translocation resulting in BCR-ABL1, a fusion oncogene [1]. BCR-ABL1 is a constitutively active cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase that drives the overproliferation of mature myeloid linage cells. Treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) effectively controls the disease in the vast majority of patients resulting in a near normal life expectancy [2]. The accurate monitoring of BCR-ABL1 transcript levels is a cornerstone of effective CML treatment. Quantitative real-time PCR-based strategies enable quantification of BCR-ABL1 transcripts to 1 residual CML cell in 1 million normal cells [3]. The quantification of residual CML has important treatment ramifications. Individuals that achieve a 3-log reduction (also referred to as major molecular response or MMR) in BCR-ABL1 transcript have exceedingly low rates of disease relapse [4]. Therefore, achieving this threshold is an important goal of TKI therapy for CML. To aid in standardized assessment of BCR-ABL1 transcripts, the international CML community developed the international scale (IS) [5]. The IS is based on 2 values, one being 100%, representing the baseline of newly diagnosed CML patients, and the other 0.1%, signifying a 3-log reduction from baseline. Based on the IS, treatment benchmarks have been established to guide therapy with treatment change recommended for those who fail to achieve specific IS benchmarks within a specified time window [6]. Additional studies have demonstrated that individuals who achieve at least a BCR-ABL1 IS value of 0.0032% (4.5 log reduction, MR4.5) can safely discontinue therapy, with approximately 50% of such patients achieving long-term treatment-free remissions [2].

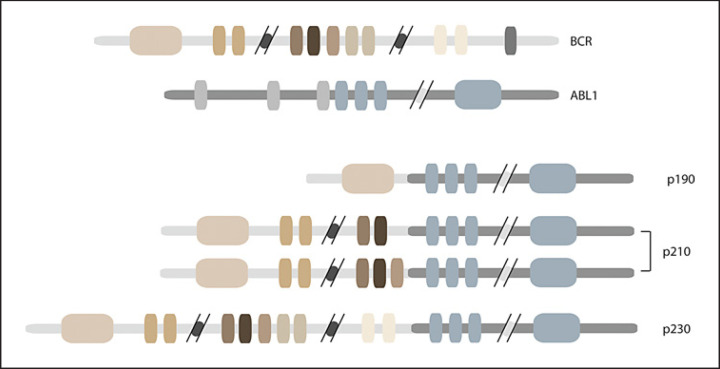

Tracking BCR-ABL1 levels is standard for monitoring response to TKI therapy; however, this becomes challenging when multiple transcripts are present. Three protein variations are found in CML based on the break points in BCR and ABL (Fig. 1). p210BCR-ABL1 is the most common in CML and typically results from a breakpoint in BCR at either exon 13 or 14 and a breakpoint in ABL1 up stream of exon 2 (e13a2 or e14a2) [7]. p190BCR-ABL1 (e1a2) is occasionally found in CML but most often is seen in patients with Ph-positive acute B lymphoid leukemia [7]. Inferior response to TKI treatment has been reported in patients with the p190BCR-ABL1 transcript [8]. Last, p230BCR-ABL1 (e19a2) is rare in CML, but when expressed, patients typically have a more indolent disease [7]. Low levels of p190BCR-ABL1 have been reported in patients with p210BCR-ABL1; however, coexistence with p230BCR-ABL1 is uncommon [9]. Further, p230BCR-ABL1 does not have an IS conversion because of its rarity. Given that specific thresholds and transcript monitoring are critical to clinical decision-making, accurate and reliable assessment of the BCR-ABL1 transcripts is vitally important. While multiple transcripts can be qualitatively identified at the time of diagnosis, quantitative monitoring of disease status can be challenging due to the varying capacity of testing facilities to measure the different transcripts [10]. Adding to this difficulty is the variable methodologies used in different testing facilities, leading to marked differences in reported transcript levels. To draw attention to these issues, we present here a case of a CML patient with multiple BCR-ABL1 transcripts, in which testing at different labs resulted in distinct differences in the reported levels of the BCR-ABL1 transcript. Herein, we discuss a management strategy to better navigate this intralab variability.

Fig. 1.

Depiction of BCR-ABL1 transcripts found in CML patients. The abbreviated BCR and ABL1 transcripts are shown at the top, while the 3 breakpoint variations found in CML patients are shown at the bottom. CML, chronic myeloid leukemia.

Case Presentation

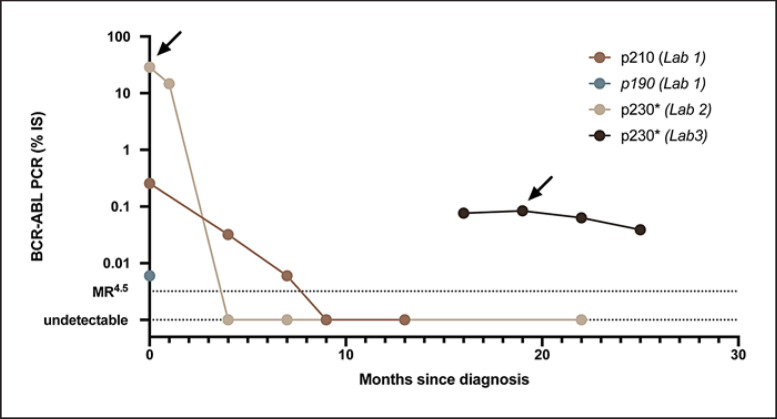

A 41-year-old female was diagnosed with CML during a routine examination when she was found to have a white blood cell count of 102,000 cells/mm3. Differential showed 36% neutrophils, 37% bands, 4% monocytes, 3% basophils, 6% metamyelocytes, 4% myelocytes, and 4% blasts. A bone marrow biopsy revealed myeloid hyperplasia with hypolobated megakaryocytes, increased M:E ratio, no increase in basophils, scattered clusters of blasts with no overall increase, and cytogenetics positive for t(9;22) consistent with chronic-phase CML. Several atypical features were noted including 75% of cells demonstrating duplication of chromosome 22 and PCR studies revealing expression of p190, p210, and p230 BCR-ABL1 isoforms. Quantitative RT-PCR at lab 1 revealed the presence of p210BCR-ABL1 and p190BCR-ABL1 at IS 0.255% and IS 0.006%, respectively (Fig. 2). Not all testing facilities offer quantification of p230BCR-ABL1, so lab 2 measured p230BCR-ABL1 at 28.8%. She was first treated with a second-generation ABL kinase inhibitor, bosutinib, at 500 mg daily. Four months after treatment, p230BCR-ABL1 was no longer detected with RT-PCR, and p210BCR-ABL1 decreased to IS 0.032%. Due to side effects, her bosutinib dose was reduced to 400 mg daily. Nine months after treatment began, p210BCR-ABL1 was also undetected. Sixteen months after treatment initiation, BCR-ABL1 monitoring was switched to lab 3, and her transcript level was once again detectable at 0.0766%. Lab 3 measures all 3 transcripts; however, the amount was too low to identify the transcript isoform. After 19 months, p230BCR-ABL1 was detected and measured as 0.0842%. Since the patient went from undetected to 0.0842% after switching testing labs, a sample taken on the same day was sent to both lab 2 and lab 3. This simultaneous analysis yielded discrepant results, with lab 3 reporting 0.063% and lab 2 reporting that BCR-ABL1 was undetectable. This discrepancy has important ramifications for clinical decision-making. If lab 2 was used solely for monitoring, the patient would be 18 months into the minimum 24-month period of MR4.5 required to attempt treatment discontinuation [6]. However, according to the other lab, she has not reached MR4.5. Indeed, her rising transcript level would otherwise be concerning for the development of TKI resistance. Ultimately, we elected to continue therapy, using lab 3 for monitoring. Twenty-five months after starting therapy, her p230BCR-ABL1 quantification at lab 3 remained stable 0.0390%.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of RT-PCR values for BCR-ABL1 transcripts. Quantification of transcripts beginning at diagnosis, separated by transcript and testing facility. *Lack of IS for transcript. →, qualitative assessment of all 3 transcripts. Lab 3 did not detect the other 2 transcripts with qualitative assessment.

Discussion

The monitoring of BCR-ABL1 transcripts in patients with an uncommon isoform represents a unique clinical challenge in CML, compounded by the lack of an IS. The precise cause of the discrepancy between lab 2 and lab 3 is unclear, but one explanation might be a difference in sensitivity between the labs. Regardless of the explanation, the discrepant results have a clear impact on clinical decision-making. First, the rise from undetectable to an MR3 would be the cause for significant concern for the development of a resistance mutation, particularly within the first 2 years of treatment initiation. Second, in an otherwise healthy young woman, TKI discontinuation would be an important clinical goal. If lab 2 were exclusively used for monitoring, she could be eligible for attempted treatment discontinuation based on the recent European Leukemia Net Guidelines [6]. However, based on the results from lab 3, the clock toward an attempt at discontinuation could not even be started. This patient's rapid response aligns with prior reports of p230BCR-ABL1 driving less-aggressive disease [7]. Indeed, she responded very well to therapy, and her p230BCR-ABL1 transcript level dropped within 4 months of treatment according to lab 2. Given the rarity of p230BCR-ABL1, the implementation of an international scale for reporting has not been possible, and thus the response over time becomes the best metric for the assessment of treatment response. If samples are sent to different labs, it becomes challenging to establish a clear trend, as described in this case. In conclusion, until standardized laboratory procedures and an international scale has been put into place for p230BCR-ABL1, we recommend monitoring patients serially at the same testing facility for a more reliable trend over time.

Statement of Ethics

It was determined by the IRB Office that this study does not require IRB review and approval. Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient for this case report.

Conflict of Interest Statement

B.J.D. has potential competing interests − SAB: Aileron Therapeutics, Boston, MA, USA; Therapy Architects (ALLCRON), Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA; Vivid Biosciences, Boston, MA, USA, Celgene, Summit, NJ, USA; RUNX1 Research Program, EnLiven Therapeutics, Boulder, Colorado; Gilead Sciences (inactive), Foster City, CA, USA; Monojul (inactive), Chicago, IL, USA; SAB & Stock: Aptose Biosciences, Toronto, Canada; Blueprint Medicines, Cambridge, MA, USA; Iterion Therapeutics, Houston, TX, USA; Third Coast Therapeutics, Chicago, IL, USA; GRAIL (SAB inactive), Menlo Park, CA, USA; Scientific Founder: MolecularMD (inactive, acquired by ICON), Dublin, Ireland; Board of Directors & Stock: Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; Board of Directors: Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Durham, NC, USA; CureOne; Joint Steering Committee: Beat AML LLS; Founder: VB Therapeutics, Tel Aviv, Israel; Clinical Trial Funding: Novartis, Basel, Switzerland; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA; Pfizer; Royalties from Patent 6958335 (Novartis exclusive license) and OHSU and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (1 Merck exclusive license). The remaining authors have no competing interests to declare.

Funding Sources

Funding was provided by K08 CA245224-01 to T.P.B, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and R01 CA065823-24 to B.J.D.

Author Contributions

B.M.S. and T.P.B. were responsible for literature review, data collection, and manuscript writing. D.B., T.P.B., and B.J.D. cared for the patient. All authors contributed to manuscript review before submission.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Konopka JB, Watanabe SM, Witte ON. An alteration of the human c-abl protein in K562 leukemia cells unmasks associated tyrosine kinase activity. Cell. 1984;37:1035–42. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90438-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campiotti L, Suter MB, Guasti L, Piazza R, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Grandi AM, et al. Imatinib discontinuation in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients with undetectable BCR-ABL transcript level: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2017;77:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Dongen JJ, Macintyre EA, Gabert JA, Delabesse E, Rossi V, Saglio G, et al. Standardized RT-PCR analysis of fusion gene transcripts from chromosome aberrations in acute leukemia for detection of minimal residual disease. Report of the BIOMED-1 Concerted Action: investigation of minimal residual disease in acute leukemia. Leukemia. 1999;13:1901–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes TP, Kaeda J, Branford S, Rudzki Z, Hochhaus A, Hensley ML, et al. Frequency of major molecular responses to imatinib or interferon alfa plus cytarabine in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1423–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes T, Deininger M, Hochhaus A, Branford S, Radich J, Kaeda J, et al. Monitoring CML patients responding to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: review and recommendations for harmonizing current methodology for detecting BCR-ABL transcripts and kinase domain mutations and for expressing results. Blood. 2006;108:28–37. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Silver RT, Schiffer C, Apperley JF, Cervantes F, et al. European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2020;34:966–84. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0776-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melo JV. The diversity of BCR-ABL fusion proteins and their relationship to leukemia phenotype. Blood. 1996;88:2375–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verma D, Kantarjian HM, Jones D, Luthra R, Borthakur G, Verstovsek S, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with P190BCR-ABL: analysis of characteristics, outcomes, and prognostic significance. Blood. 2009;114:2232–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Rhee F, Hochhaus A, Lin F, Melo JV, Goldman JM, Cross NC. p190 BCR-ABL mRNA is expressed at low levels in p210-positive chronic myeloid and acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Blood. 1996;87:5213–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burmeister T, Reinhardt R. A multiplex PCR for improved detection of typical and atypical BCR-ABL fusion transcripts. Leuk Res. 2008;32:579–85. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.