Abstract

Background

We evaluated the risk of developing primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) according to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) status in patients with prostate cancer.

Materials and methods

From the nationwide claims database in South Korea, 218,203 men with prostate cancer were identified between 2008 and 2017. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 170,701 patients (42,877 in the ADT and non-ADT groups and 127,824 in the non-ADT group) were included in the analysis. To adjust for comorbidities between cohorts, exact matching was performed. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of POAG associated with ADT after controlling for potential confounding factors.

Results

In the matched cohort, the ADT group had a lower proportion of newly developed POAG than the non-ADT group (2.10% vs. 2.88%, respectively; P < 0.0001). Multivariable analysis revealed that the ADT group had a significantly lower risk of POAG than the non-ADT group (HR, 0.808; 95% CI, 0.739–0.884; P < 0.0001). The risk of POAG was lower in patients who underwent ADT for less than 2 years (HR, 0.782; 95% CI, 0.690–0.886; P = 0.0001) and in those receiving ADT for over 2 years (HR, 0.825; 95% CI, 0.744–0.916; P = 0.0003) compared with the non-ADT group.

Conclusions

The use of ADT was associated with a decreased risk of POAG in Korean patients with prostate cancer. Our findings suggest that testosterone may be involved in the pathophysiology of POAG, and this should be confirmed through further studies.

Keywords: Glaucoma, Prostate cancer, Testosterone

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common malignancy in men and the fifth leading cause of cancer-specific death.1 Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is the standard treatment for patients with advanced and metastatic prostate cancer, and it can be offered to patients with locally advanced disease in combination with surgery or radiation therapy.2, 3, 4 ADT is performed either surgically or medically, and both ADT strategies are comparable in their ability to achieve a castrate-level of testosterone; however, currently, medical ADT using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist is the mainstay of ADT.5 Almost all prostate cancers begin in an androgen-dependent state; therefore, ADT results in improved oncological outcomes. However, a decrease in testosterone levels has a negative effect on lipid, glucose, muscle, and bone metabolism, resulting in a variety of adverse effects, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, sarcopenia, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease.6

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is a major cause of irreversible blindness worldwide.7 It is a chronic, progressive optic neuropathy characterized by progressive retinal ganglion cell death and visual field loss. This neuropathy is generally considered a multifactorial disease caused by local, systemic, genetic, and environmental factors.8, 9, 10 Two main mechanisms have been proposed to underlie the development of POAG: a mechanical theory with a focus on high intraocular pressure (IOP) and a vascular theory that emphasizes disturbances in ocular blood flow (OBF).11 Recent studies have demonstrated that other systemic risk factors for glaucoma include metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and arterial stiffness.10 Meanwhile, the effects of sex hormones on OBF and IOP in POAG have been discussed.12 Although conflicting data exist on the prevalence of POAG among men and women, a recent meta-analysis revealed that POAG was more common in men than in women, suggesting that sex hormones may play a potential role in regulating OBF and IOP.13,14 Estrogen is known to be associated with higher OBF, lower IOP, and neuroprotective properties; however, there is no consensus on the effects of testosterone on ocular health, including POAG.15

As the average lifespan increases, prostate cancer and POAG are increasingly important public health problems,16 and they share common risk factors such as age and metabolic syndrome.6,10 In this regard, the ocular health of prostate cancer patients treated with ADT may be a significant issue in the potential relationship between testosterone and OBF/IOP. To date, no study has investigated the relationship between ADT and glaucoma. We evaluated the risk of POAG development according to ADT use in patients with prostate cancer using the nationwide health insurance claims database in Korea.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data sources

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gangnam Severance Hospital (No. 3-2019-0339) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The National Health Insurance System in South Korea is a universal health coverage system that covers nearly all Korean residents. The Health Insurance and Review Assessment (HIRA) in South Korea, also referred to as National Health Insurance data, is a repository of claims data collected in the process of reimbursing health care providers. The HIRA contains comprehensive data on health care services, such as treatment, pharmaceuticals, procedures, and diagnoses, for almost 50 million beneficiaries.17

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), codes were used to identify eligible patients for analysis. Between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2017, a total of 218,203 men with primary malignant prostate cancer (ICD-10 code C61.0) were identified from the HIRA database. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) patients diagnosed with prostate cancer before 2008 (n = 22,895), (2) patients who underwent orchiectomy (n = 1,112), and (3) patients with a prior history of glaucoma and POAG occurring within 3 months from the index date (n = 23,495). In our study, patients who underwent orchiectomy were excluded because surgical castration accounted for an extremely small proportion of patients in Korea, and we wanted to focus on the effect of medical castration on POAG.

2.3. Definition of groups, outcomes, and covariates

The study cohort was divided into ADT and non-ADT groups. The ADT group was defined as those who received at least one dose of GnRH agonist or antagonist after the diagnosis of prostate cancer. The cumulative dose of ADT was calculated as the sum of the action periods for each ADT preparation. POAG and other comorbidities were identified using ICD-10 diagnostic codes (Supplementary Table 1). The incidence of POAG was ascertained 90 days after the index date. Adjustment covariates included patient age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, migraine, chronic liver disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. Medication history including GnRH agonist or antagonist and antiandrogen was identified using billing codes in the HIRA database (Supplementary Table 1).

2.4. Statistical analysis

The index date was defined as the date of first ADT use in the ADT group and the date of prostate cancer diagnosis in the non-ADT group. We defined the end of follow-up as the date at which the event occurred, or if the event did not occur, the date of the last valid inpatient or outpatient record. To adjust for comorbidity between cohorts, 1:1 exact matching was performed. Statistical comparisons of continuous variables from patient demographic information were carried out using the Student t test, and categorical variables were compared using Pearson's Chi-square test. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of events associated with ADT, controlling for potential confounders. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated to examine the cumulative incidence of outcomes according to ADT use and ADT duration. Meanwhile, when there was a difference in the definition of index date between the two groups, supplementary analyses were performed after adjusting for follow-up duration, as follows. In the ADT group, the median time to ADT use from the time of prostate cancer diagnosis was 24 days; thus, the adjusted index date for non-ADT users was defined as the date of prostate cancer diagnosis plus the median time to ADT use in our study.18 As a sensitivity analysis, a time-varying Cox regression analysis was also performed to reduce immortal time bias.19 Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, and all statistical tests were two sided. All study analyses were performed using strategic application system (SAS) for Windows, version 9.4.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

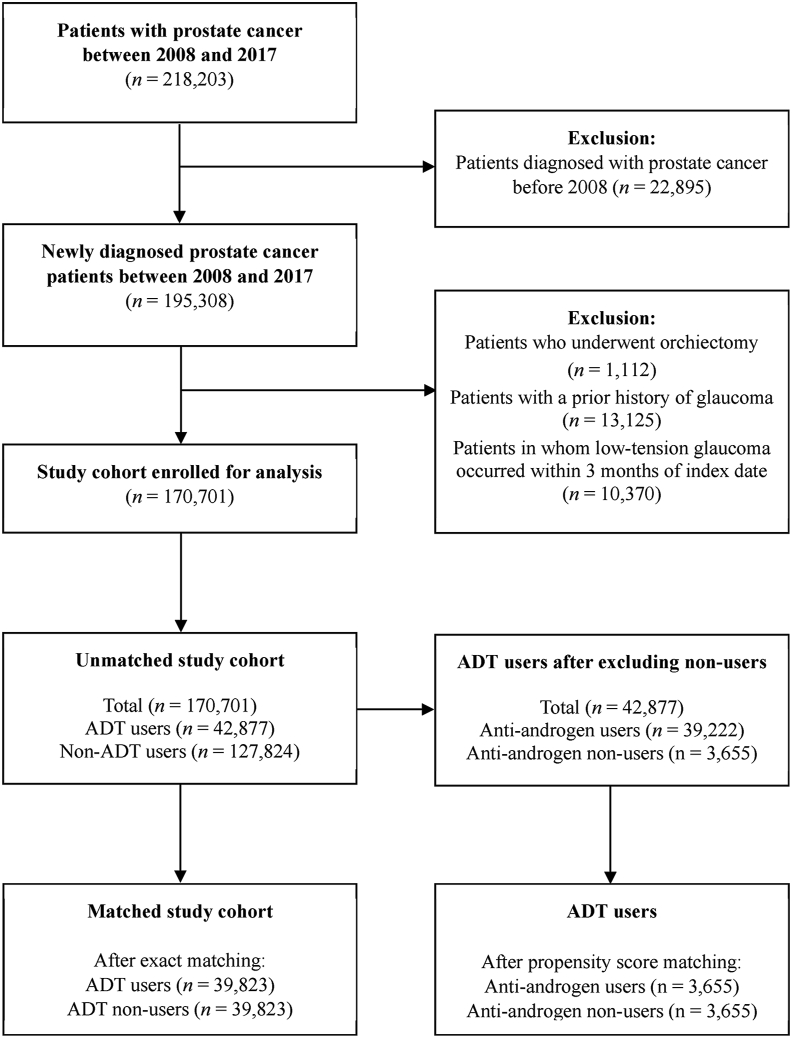

A total of 170,701 men with prostate cancer fulfilled all inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of these patients, 42,877 belonged to the ADT group and 127,824 were in the non-ADT group. After 1:1 exact matching, 39,823 patients from each group were selected. In the matched cohort, there were no significant differences in baseline covariates between the two groups, except for follow-up (3.58 ± 2.49 years in the ADT group vs. 3.98 ± 2.75 years in the non-ADT group; P < 0.0001; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study cohort. ADT, androgen deprivation therapy.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study cohort

| Variables | Before matching |

After exact matching |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADT (n = 42,877) | Non-ADT (n = 127,824) | P value | ADT (n = 39,823) | Non-ADT (n = 39,823) | P value | |

| Age (years)∗ | 72.72 ± 8.02 | 64.86 ± 10.26 | <0.0001 | 72.09 ± 7.80 | 72.09 ± 7.80 | >0.9999 |

| Follow-up (years)∗ | 3.52 ± 2.47 | 4.32 ± 2.82 | <0.0001 | 3.58 ± 2.49 | 3.98 ± 2.75 | <0.0001 |

| ADT, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 0 (0.00) | 127,824 (100) | – | 0 (0.00) | 39,823 (100) | – |

| <2 years | 24,607 (57.39) | 0 (0.00) | – | 22,700 (57.00) | 0 (0.00) | – |

| ≥2 years | 18,270 (42.61) | 0 (0.00) | – | 17,123 (43.00) | 0 (0.00) | – |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 18,164 (42.36) | 43,785 (34.25) | <0.0001 | 16,360 (41.08) | 16,360 (41.08) | >0.9999 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 15,795 (36.84) | 42,300 (33.09) | <0.0001 | 14,515 (36.45) | 14,515 (36.45) | >0.9999 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 17,036 (39.73) | 52,918 (41.40) | <0.0001 | 15,657 (39.32) | 15,657 (39.32) | >0.9999 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 8870 (20.69) | 24,728 (19.35) | <0.0001 | 7889 (19.81) | 7889 (19.81) | >0.9999 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 6521 (15.21) | 14200 (11.11) | <0.0001 | 5495 (13.80) | 5495 (13.80) | >0.9999 |

| Migraine, n (%) | 3309 (7.72) | 10171 (7.96) | 0.1114 | 2594 (6.51) | 2594 (6.51) | >0.9999 |

| Chronic liver disease, n (%) | 4483 (10.46) | 16,219 (12.69) | <0.0001 | 3860 (9.69) | 3860 (9.69) | >0.9999 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, n (%) | 2732 (6.37) | 8253 (6.46) | 0.5357 | 2088 (5.24) | 2088 (5.24) | >0.9999 |

| Open-angle glaucoma, n (%) | 906 (2.11) | 3416 (2.67) | <0.0001 | 836 (2.10) | 1147 (2.88) | <0.0001 |

ADT, androgen deprivation therapy.

∗Data presented as mean ± standard deviation.

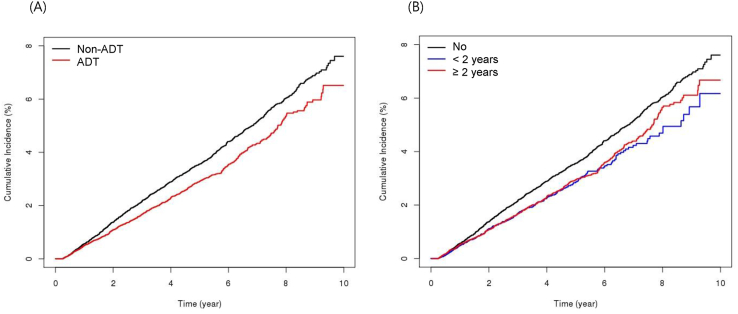

3.2. POAG risk in ADT versus non-ADT groups

In the matched cohort, the ADT group had a lower proportion of patients with newly developed POAG than the non-ADT group (2.10% vs. 2.88%, respectively; P < 0.0001; Table 1). Multivariable analysis revealed that the ADT group had a significantly lower risk of POAG than the non-ADT group (HR, 0.808; 95% CI, 0.739–0.884; P < 0.0001; Table 2, Fig. 2A). The risk of POAG was lower in patients who underwent ADT for less than 2 years (HR, 0.782; 95% CI, 0.690–0.886; P = 0.0001) and in those who underwent ADT for over 2 years (HR, 0.825; 95% CI, 0.744–0.916; P = 0.0003) than in the non-ADT group (Table 2, Fig. 2B). A history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia was associated with an increased risk of POAG (Table 2). After adjusting for follow-up duration in the non-ADT group, the beneficial effect of ADT in terms of POAG was still apparent (Table 3). As a sensitivity analysis, the time-varying Cox regression analysis confirmed the previously mentioned statistical findings without any significant difference (data not shown).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis for open-angle glaucoma in the matched study cohort

| Variables | Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADT |

Duration of ADT |

|||||

| HR (95% CIs) | P value | HR (95% CIs) | P value | HR (95% CIs) | P value | |

| Age | 1.014 (1.008–1.020) | <0.0001 | 1.013 (1.007–1.019) | <0.0001 | 1.013 (1.007–1.019) | <0.0001 |

| ADT (yes vs. no) | 0.818 (0.748–0.895) | <0.0001 | 0.808 (0.739–0.884) | <0.0001 | ||

| Duration of ADT | ||||||

| No | Ref. | – | – | – | Ref. | – |

| <2 years | 0.796 (0.703–0.902) | 0.0003 | – | – | 0.782 (0.690–0.886) | 0.0001 |

| ≥2 years | 0.832 (0.750–0.923) | 0.0005 | – | – | 0.825 (0.744–0.916) | 0.0003 |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | 1.326 (1.202–1.462) | <0.0001 | 1.206 (1.089–1.336) | 0.0003 | 1.207 (1.090–1.337) | 0.0003 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes vs. no) | 1.331 (1.216–1.457) | <0.0001 | 1.239 (1.128–1.360) | <0.0001 | 1.239 (1.128–1.360) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia (yes vs. no) | 1.272 (1.161–1.393) | <0.0001 | 1.167 (1.059–1.286) | 0.0019 | 1.168 (1.059–1.287) | 0.0018 |

| Cardiovascular diseases (yes vs. no) | 1.143 (1.023–1.277) | 0.0185 | 1.024 (0.913–1.148) | 0.6849 | 1.024 (0.914–1.148) | 0.682 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases (yes vs. no) | 1.125 (0.988–1.282) | 0.0765 | 1.011 (0.885–1.155) | 0.8709 | 1.011 (0.885–1.154) | 0.8741 |

| Migraine (yes vs. no) | 1.116 (0.927–1.345) | 0.2474 | 1.066 (0.884–1.285) | 0.5026 | 1.066 (0.885–1.285) | 0.4993 |

| Chronic liver disease (yes vs. no) | 1.103 (0.948–1.283) | 0.2056 | 1.065 (0.914–1.240) | 0.4203 | 1.065 (0.914–1.241) | 0.4174 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (yes vs. no) | 1.200 (0.984–1.464) | 0.0717 | 1.134 (0.929–1.384) | 0.2152 | 1.135 (0.930–1.385) | 0.2127 |

ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of primary open-angle glaucoma according to the use of ADT (A) and the duration of ADT (B). ADT, androgen deprivation therapy.

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis of open-angle glaucoma in the matched study cohort after adjusting for follow-up duration of non-ADT group

| Variables | Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADT |

Duration of ADT |

|||||

| HR (95% CIs) | P value | HR (95% CIs) | P value | HR (95% CIs) | P value | |

| Age | 1.014 (1.008–1.019) | <0.0001 | 1.013 (1.007–1.019) | <0.0001 | 1.013 (1.007–1.019) | <0.0001 |

| ADT (yes vs. no) | 0.803 (0.734–0.878) | <0.0001 | 0.792 (0.725–0.866) | <0.0001 | ||

| Duration of ADT | ||||||

| No | Ref. | – | – | – | Ref. | – |

| <2 years | 0.778 (0.687–0.881) | <0.0001 | – | – | 0.763 (0.673–0.864) | <0.0001 |

| ≥2 years | 0.819 (0.738–0.909) | 0.0002 | – | – | 0.812 (0.731–0.901) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | 1.325 (1.201–1.461) | <0.0001 | 1.206 (1.089–1.336) | 0.0003 | 1.208 (1.090–1.338) | 0.0003 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes vs. no) | 1.330 (1.215–1.456) | <0.0001 | 1.239 (1.128–1.360) | <0.0001 | 1.239 (1.128–1.361) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia (yes vs. no) | 1.271 (1.161–1.393) | <0.0001 | 1.167 (1.059–1.287) | 0.0018 | 1.168 (1.060–1.288) | 0.0018 |

| Cardiovascular diseases (yes vs. no) | 1.143 (1.022–1.277) | 0.0187 | 1.024 (0.913–1.148) | 0.6838 | 1.024 (0.914–1.148) | 0.6804 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases (yes vs. no) | 1.125 (0.987–1.282) | 0.0772 | 1.011 (0.885–1.155) | 0.8722 | 1.011 (0.885–1.154) | 0.8758 |

| Migraine (yes vs. no) | 1.116 (0.926–1.344) | 0.2481 | 1.066 (0.885–1.285) | 0.5012 | 1.067 (0.885–1.286) | 0.4974 |

| Chronic liver disease (yes vs. no) | 1.103 (0.948–1.283) | 0.2063 | 1.065 (0.914–1.241) | 0.4192 | 1.065 (0.915–1.241) | 0.4159 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (yes vs. no) | 1.200 (0.984–1.463) | 0.0718 | 1.134 (0.930–1.384) | 0.2147 | 1.135 (0.930–1.385) | 0.2119 |

ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

3.3. Antiandrogens and POAG risk in the ADT group

Antiandrogens are a class of drugs that prevent androgens from having their biological effects on the body. In the ADT group (n = 42,877), antiandrogens were concurrently prescribed to most patients in the ADT group (n = 39,222, 91.5%). Because there was multicollinearity between ADT and antiandrogen use, antiandrogen use was not included as a covariate in the main analysis. Subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between antiandrogens and the risk of POAG. In the ADT group, antiandrogen users and nonusers were selected using a 1:1 propensity score matching with age and ADT duration. The number of antiandrogen users and nonusers was 3,655 (Supplementary Table 2). In the multivariable Cox regression analysis, there was no difference in the risk of developing POAG between antiandrogen users and nonusers (Supplementary Table 3).

4. Discussion

In this large population-based study, we found that the incidence of newly developed POAG was reduced in patients with prostate cancer treated with ADT. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first attempt to reveal the relationship between ADT and POAG. Given that ADT may cause metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome is known to be an important risk factor for POAG,6,10 the present findings might be surprising. However, our findings seem to be in line with the male predominance in patients with POAG in epidemiologic studies. According to Rudnicka et al‘s meta-analysis, the overall prevalence of POAG in men was 1.37 times that in women (95% CI, 1.22–1.53) after adjusting for age, race, publication year, and survey methods.13 Another meta-analysis by Tahm et al also revealed that men were more likely to have POAG than women after adjusting for age, geographic region, habitat type, ethnicity, response rate, and year of study (odds ratio, 1.36; 95% credible interval, 1.23–1.52).14 Taken together, it could be postulated that castration-level testosterone may be beneficial for regulating either IOP or OBF, thus preventing the development of POAG. Although it is still uncertain how ocular health is affected by testosterone, the alteration of the sex hormone milieu might be involved in the pathophysiology of POAG.

Several researchers have investigated the relationship between testosterone and IOP, but the role of testosterone in POAG remains unclear. Knepper et al demonstrated that topical administration of dexamethasone to rabbit eyes increased IOP, but testosterone administration did not. They noted that a change in the aqueous outflow pathway might be an essential cause of elevated IOP in dexamethasone-treated eyes.20 Systemic testosterone replacement therapy had no significant effect on IOP in men with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.21 As this study was based on short-term treatment for 3 months, there was a limitation in determining the long-term effects of testosterone replacement therapy on IOP. However, a recently published observational study showed that IOP was significantly associated with testosterone, and the IOP in patients with testosterone above 3.0 ng/mL was significantly higher than that in patients with testosterone levels below 3.0 ng/mL. The authors mentioned that one of the causes of IOP elevation is that testosterone inhibits the activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the trabecular meshwork, thereby lowering outflow capacity.22 Studies with female participants have produced interesting results. Toker et al demonstrated that higher testosterone levels were associated with higher IOP in women receiving hormone replacement therapy and in those not receiving hormone replacement therapy.23 The Nurses’ Health Study also demonstrated that higher testosterone levels were significantly associated with higher IOP and higher POAG risk in postmenopausal women.24 Newman-Casey et al evaluated the association between postmenopausal hormone use and the risk of POAG.25 They showed that hormone replacement with estrogen alone was associated with a 40% reduced risk for POAG, but the risk of POAG did not differ when using estrogen in combination with androgen. This suggests that the beneficial effect of estrogen on risk reduction in POAG might be diminished by the addition of androgens.

In addition to elevated IOP, disturbances in OBF have been suggested as one of the mechanisms of POAG development.11 Under the vascular theory of glaucoma, glaucomatous optic neuropathy can occur as a consequence of insufficient blood supply because of elevated IOP or other risk factors. Although OBF studies in glaucoma are difficult to summarize because researchers use different techniques to measure and study different types of glaucoma, most published studies found an average reduction in ocular perfusion in glaucoma patients.11 Theoretically, there are three possibilities for a reduction in OBF in POAG patients: (1) increase in flow resistance, (2) decrease in perfusion pressure, and (3) increase in blood viscosity.11 The size of local vessels regulates the changes in flow resistance, and some studies have observed a link between testosterone and vascular regulation. Kelly et al demonstrated that testosterone enhances nitric oxide production by expressing or activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase, resulting in a vasodilatory response of retinal vessels in animal experiments.26 Malan et al showed that testosterone has the potential to induce an independent vasodilatory response in retinal vessels.27 Meanwhile, the effect of testosterone on cerebral blood flow may be similar to its effect on the eye.15 Thus, the effect of testosterone on the eye may be obtained by extrapolating from relevant studies on cerebral blood flow. In this respect, several studies have expressed opposing opinions. Gonzales et al showed that long-term treatment with testosterone promoted the vasoconstrictor mechanism of the middle cerebral arteries in humans.28 In addition, male rodents reported increased vascular tone in the middle cerebral arteries compared with that in female rodents.28 This suggests that the effect of testosterone on vascular tone can be vasodilation in acute, but vasoconstriction in chronic. These results suggest that prolonged exposure to testosterone may lead to blood vessel remodeling or spasms, resulting in increased flow resistance and decreased OBF.

Our study had several advantages. We analyzed a nationwide claims database with large sample size and a relatively long follow-up period, and the database includes nearly all prostate cancer patients in Korea for 10 years. To reduce confounding bias, we strictly restricted the study cohort and attempted meticulous matching between the two groups with various covariates, which were closely associated with POAG risk. As mentioned earlier, the present study is the first to demonstrate the relationship between ADT and POAG. Nevertheless, there are some limitations to our study. Although the present study found that ADT is associated with a reduction in POAG risk, the causal relationship is still uncertain because of the inherent limitations of an observational study. Our study did not show the serum testosterone level of the individuals because the HIRA database does not contain individual's laboratory values. Although the majority of prostate cancer patients during ADT achieve the castrate level of serum testosterone, it is known that some patients fail to do so. In this perspective, the relationship between serum testosterone level and POAG risk should be assessed in prospectively designed clinical studies. In addition, the claims data did not provide relevant lifestyle factors, such as smoking or obesity, or other clinical data, including IOP, blood pressure, and other laboratory values, which might affect our estimates. Further clinical studies and experimental research are needed to address this point and to prove the relationship between ADT and POAG.

5. Conclusion

The use of ADT was associated with a decreased risk of POAG in Korean patients with prostate cancer. Our findings suggest that testosterone may be involved in the pathophysiology of POAG, and this should be confirmed through further studies. This positive effect of ADT is expected to be applied in the field of glaucoma prevention and the development of novel treatments.

Conflicts of interest

All of the authors declare that they have no conflict of interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the 2019 Research Grant of the Korean Prostate Society.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prnil.2021.05.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rawla P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J Oncol. 2019;10(2):63–89. doi: 10.14740/wjon1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolla M., Collette L., Blank L., Warde P., Dubois J.B., Mirimanoff R.O., et al. Long-term results with immediate androgen suppression and external irradiation in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer (an EORTC study): a phase III randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):103–106. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09408-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn S., Lee M., Jeong C.W. Comparative quality-adjusted survival analysis between radiation therapy alone and radiation with androgen deprivation therapy in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer: a secondary analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 85-31 with novel decision analysis methods. Prostate Int. 2018;6(4):140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warde P., Mason M., Ding K., Kirkbride P., Brundage M., Cowan R., et al. Combined androgen deprivation therapy and radiation therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2104–2111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61095-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borno H.T., Lichtensztajn D.Y., Gomez S.L., Palmer N.R., Ryan C.J. Differential use of medical versus surgical androgen deprivation therapy for patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(3):453–462. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitsuzuka K., Arai Y. Metabolic changes in patients with prostate cancer during androgen deprivation therapy. Int J Urol. 2018;25(1):45–53. doi: 10.1111/iju.13473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quigley H.A., Broman A.T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teikari J.M. Genetic influences in open-angle glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1990;30(3):161–168. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199030030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinreb R.N., Aung T., Medeiros F.A. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1901–1911. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leske M.C. Open-angle glaucoma -- an epidemiologic overview. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2007;14(4):166–172. doi: 10.1080/09286580701501931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flammer J., Orgül S., Costa V.P., Orzalesi N., Krieglstein G.K., Serra L.M., et al. The impact of ocular blood flow in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2002;21(4):359–393. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126(4):487–497. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudnicka A.R., Mt-Isa S., Owen C.G., Cook D.G., Ashby D. Variations in primary open-angle glaucoma prevalence by age, gender, and race: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(10):4254–4261. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tham Y.C., Li X., Wong T.Y., Quigley H.A., Aung T., Cheng C.Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel P., Harris A., Toris C., Tobe L., Lang M., Belamkar A., et al. Effects of Sex Hormones on Ocular Blood Flow and Intraocular Pressure in Primary Open-angle Glaucoma: A Review. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(12):1037–1041. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resnikoff S., Pascolini D., Etya'ale D., Kocur I., Pararajasegaram R., Pokharel G.P., et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):844–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J.A., Yoon S., Kim L.Y., Kim D.S. Towards Actualizing the Value Potential of Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) Data as a Resource for Health Research: Strengths, Limitations, Applications, and Strategies for Optimal Use of HIRA Data. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32(5):718–728. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.5.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nead K.T., Gaskin G., Chester C., Swisher-McClure S., Dudley J.T., Leeper N.J., et al. Androgen Deprivation Therapy and Future Alzheimer's Disease Risk. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):566–571. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho I.S., Chae Y.R., Kim J.H., Yoo H.R., Jang S.Y., Kim G.R., et al. Statistical methods for elimination of guarantee-time bias in cohort studies: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0405-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knepper P.A., Collins J.A., Frederick R. Effects of dexamethasone, progesterone, and testosterone on IOP and GAGs in the rabbit eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26(8):1093–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gokce G., Hurmeric V., Mumcuoglu T., Ozge G., Basaran Y., Unal H.U., et al. Effects of androgen replacement therapy on cornea and tear function in men with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Postgrad Med. 2015;127(4):376–380. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2015.1033376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J.S., Lee M.H., Kim J.H., Jo Y.J., Shin J.H., Park H.J. Cross Sectional Study among Intraocular Pressure, Mean Arterial Blood Pressure, and Serum Testosterone according to the Anthropometric Obesity Indices in Korean Men. World J Mens Health. 2020;38:e51. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.200066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toker E., Yenice O., Temel A. Influence of serum levels of sex hormones on intraocular pressure in menopausal women. J Glaucoma. 2003;12(5):436–440. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang J.H., Rosner B.A., Wiggs J.L., Pasquale L.R. Sex hormone levels and risk of primary open-angle glaucoma in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2018;25(10):1116–1123. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman-Casey P.A., Talwar N., Nan B., Musch D.C., Pasquale L.R., Stein J.D. The potential association between postmenopausal hormone use and primary open-angle glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(3):298–303. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.7618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly D.M., Jones T.H. Testosterone: a vascular hormone in health and disease. J Endocrinol. 2013;217(3):R47–R71. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malan N.T., Smith W., von Kanel R., Hamer M., Schutte A.E., Malan L. Low serum testosterone and increased diastolic ocular perfusion pressure: a risk for retinal microvasculature. Vasa. 2015;44(6):435–443. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzales R.J. Androgens and the cerebrovasculature: modulation of vascular function during normal and pathophysiological conditions. Pflugers Arch. 2013;465(5):627–642. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.