Abstract

The light induced nitric oxide (NO) release properties of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) and S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) NO donors doped within polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) films (PDMS-SNAP and PDMS-GSNO respectively) for potential inhaled NO (iNO) applications is examined. To achieve photolytic release of gas phase NO from the PDMS-SNAP and PDMS-GSNO films, narrow-band LED light sources are employed and the NO concentration in a N2 sweep gas above the film is monitored with an electrochemical NO sensor. The NO release kinetics using LED sources with different nominal wavelengths and optical power densities are reported. The effect of the NO donor loading within the PDMS films is also examined. The NO release levels can be controlled by the LED triggered release from the NO donor-doped silicone rubber films in order to generate therapeutic levels in a sweep gas for suitable durations potentially useful for iNO therapy. Hence this work may lay the groundwork for future development of a highly portable iNO system for treatment of patients with pulmonary hypertension, hypoxemia, and cystic fibrosis.

Keywords: Nitric oxide, S-nitrosothiol, SNAP, GSNO, Photo release, Gas phase, Inhalation NO

1. Introduction

The endothelium-derived relaxing factor, nitric oxide, is not only a potent pulmonary vasodilator [1,2], but also has substantial broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity [3]. For treating pulmonary hypertension and hypoxemia, typically 1–80 ppm of gas phase NO is used for inhalation therapy in a hospital setting [4]. Recently, more evidence suggests that NO is also effective for treatment of pulmonary infections in pathological conditions where endogenous NO production is impaired by chronic diseases [5–7]. As an adjunctive therapy, low-dose iNO with antibiotics has proven to be effective to disperse Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm in the lungs of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients [8]. However, one remaining challenge is that iNO therapy at present is quite expensive (> $3000 per day) [9] owing to costly NO cylinders and the associated long-term instability of NO in such tanks. Therefore, the current NO delivery technology that utilizes compressed NO tanks is both expensive and non-portable for routine in-home use/care.

In-situ real-time NO gas generation could expand the potential and use of iNO therapy. Various chemical species, such as nitrites and S-nitrosothiols, have the potential to be utilized as a reservoir for iNO that can have controlled gas phase NO delivery upon use of the appropriate stimulus/catalyst. For example, the Meyerhoff group recently developed a method for electrochemical gas phase NO generation via copper (II)-tri(2-pyridylmethyl)amine mediated reduction of nitrite [10,11]. Another attractive strategy for NO delivery is to generate NO from NO donor molecules like S-nitrosothiols (RSNOs). The RSNO donors, such as SNAP or GSNO, have proven stability in solid form and can emit NO gas spontaneously by thermal decomposition, in the presence of metal ion catalysts (e.g., Cu(I)) and/or reducing agents (e.g., thiols, ascorbate) [12,13], or by photolytic activation [14]. Thermal decomposition of SNAP has already been utilized for preparing thromboresistant and antimicrobial catheters [15–17] and implantable sensors [18]. By incorporating copper nanoparticles within the catheter material the decomposition rate of the NO donor can be enhanced, and the NO flux through the catheter walls can be significantly increased [19].

The light induced NO release from RSNOs is very attractive but has less frequently been examined. RSNOs have absorption maxima at wavelengths around 340 nm (1(n,π*)) and 520–590 nm (1(π,π*)), and these wavelengths have been primarily associated with their decomposition [20,21]. Frost et al. used incandescent light for controlled release of NO from SNAP derivatized fumed silica particles blended into silicone rubber [22]. Later Gierke et al. [23] covalently linked SNAP to PDMS and used LED light with a 470 nm nominal wavelength for releasing the NO payload into an aqueous solution. Recently, we demonstrated light activated NO release from SNAP doped biodegradable poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres for injectable and topical use [24]. Gas phase delivery via photolysis of RSNO doped into silicone rubber films has not been reported thus far.

This study focuses on investigating the feasibility of light-induced controlled release of NO, with potential use for iNO therapy, utilizing RSNO-loaded silicone rubber as the NO reservoir. To accomplish this, we investigated the effect of light frequency and formulation variables of SNAP and GSNO-loaded silicone rubber films on the NO emission rate. These results demonstrate that the data derived from this model system can potentially be used to scale-up the NO release into a sweep gas at rates that may be useful for creating a highly portable and inexpensive iNO therapy system.

2. Materials and methods

SNAP was purchased from Pharmablock (USA). Solid GSNO was prepared from reduced l-glutathione (Sigma, USA) as described by T.W. Hart [25] and micronized with mortar and pestle. The purity of NO donors was determined via UV/VIS, after dissolving known amount of the NO donor in 10 mM phosphate buffer containing 2.7 mM potassium chloride, 137 mM sodium chloride and 0.01 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 7.4, and measuring the absorbance of the solution (SNAP: A340 = 1075 M−1 cm−1 [26], GSNO: A334 = 800 M−1 cm−1 [25]).

To prepare silicone films, the base and curing agent of a silicone elastomer (Sylgard® 184 Dow Corning) were mixed at a 10:1 w/w ratio before adding solid SNAP or GSNO (< 260 μm particle size). The mixture was then thoroughly blended with a disposable spatula for 10 min in a 50 mL conical centrifuge tube and degassed in vacuum (1.4 mbar absolute pressure), and then poured into Petri dishes, degassed again, and then cured at room temperature for at least 24 h. After curing, the films were placed into vacuum (1.4 mbar absolute pressure, NAPCO Model 5831 vacuum oven) at room temperature for another 24 h in order to remove any volatile residues from the films. The prepared films were stored at room temperature in the dark. During the whole fabrication process the light exposure of the doped films was minimized by working in dimmed light conditions and using aluminum foil to prevent decomposition of the NO donors.

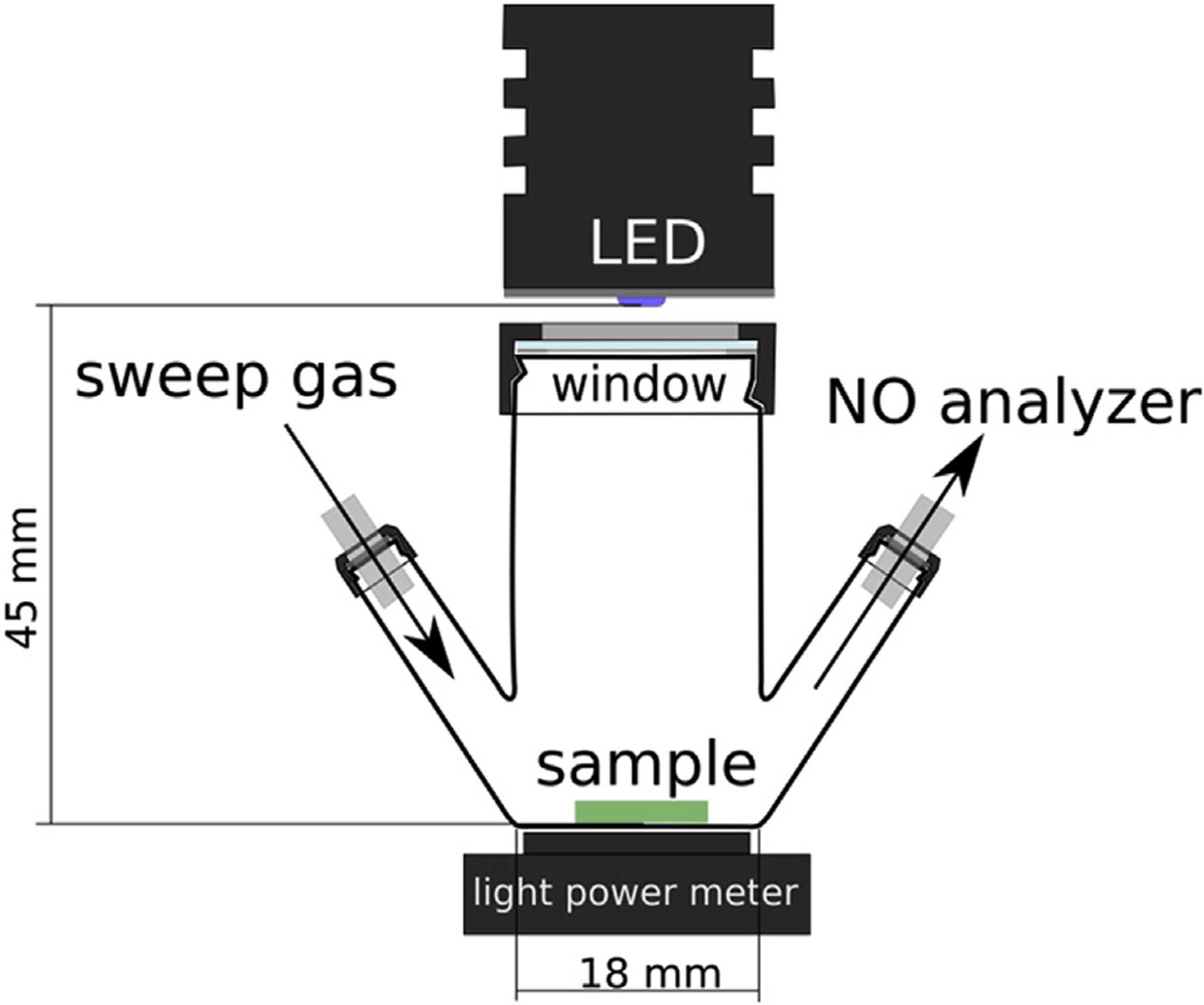

Typically, 3 or 6 mm diameter circular test pieces, with 6.7 (± 1.0) mg and 22.8 (± 3.6) mg weight, respectively, were cut from the parent PDMS-SNAP or PDMS-GSNO films using a biopsy punch for testing their NO release properties. The test piece was placed into a test chamber directly onto the bottom of the cell or onto a MicroCloth (Buehler) surface placed on the bottom of the cell (see Fig. 1). An LED light source was irradiated onto the test piece through a quartz window. For testing the effect of different wavelengths, Thorlabs M340L4, M385LP1, M470L3, M565L3 LED light sources, with nominal wavelengths of 340 nm, 385 nm, 470 nm and 565 nm, respectively, were used with a LEDD1B T-Cube driver. The optical power density was set to a given value using a Thorlabs PM-16-401 calibrated optical power meter equipped with volume absorber and a 10 mm input aperture prior to placing the test piece into the chamber. The light source was turned on after 120 s baseline measurement.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of photolysis cell for light-activated NO release.

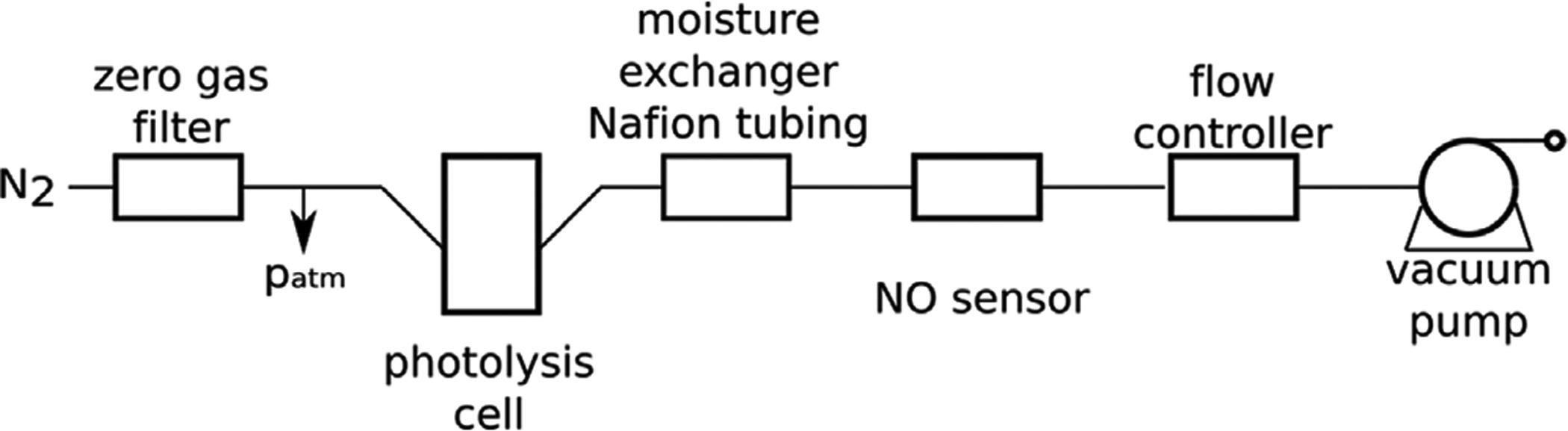

The generated NO was purged out from the chamber using nitrogen as the sweep gas (ultra-high purity, Cryogenic Gases) after first passing the N2 through a zero-gas filter cartridge containing activated charcoal. In order to maintain near atmospheric pressure in the photolysis cell and NO sensor, a “T” element with N2 overflow was placed into the setup before the photolysis cell. In order to maintain the humidity of the sample gas flow in the range required for the electrochemical gas sensor, it was passed through a 60 cm long 0.060” Nafion™ tubing (PermaPure) before accessing the sensor. The concentration of NO in the gas stream was measured using an electrochemical NO gas sensor (Alphasense, NO-B4) (Fig. 2). The flow rate of the N2 sweep gas was controlled using a mass flow controller (Alicat MCS) placed between the sensor and the vacuum pump (Tetra Whisper 10, converted for vacuum). The flow rate of the N2 recipient gas was set at 200 SCCM in this initial model system. Standard gas condition was considered as 101,325 Pa and 298.15 K. The amperometric NO gas sensor was equipped with an individual sensor board (Alphasense ISB) providing a +200 mV bias voltage for the sensor and converting the sensor output current to an output voltage signal. The output signal was digitalized using a 16-bit analog-digital converter (Adafruit ADS1115) and recorded with an Arduino compatible microcontroller (Ruggeduino-SE, Rugged Circuits) equipped with a data logging shield (Adafruit). The electrochemical NO gas sensor was calibrated typically with 6.0 ppm NO gas diluted from a 43.2 ppm primary standard (balance nitrogen; commercial cylinder from Cryogenic Gases) or using a 4.9 ppm NO (balance nitrogen; from Cryogenic Gases) primary standard directly. For diluting the calibration gas with nitrogen gas, Alicat MCS Series mass flow controllers were used.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of NO release and electrochemical gas sensor set up.

UV-VIS transmittance of the PDMS-SNAP and PDMS-GSNO films was measured with a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 35 spectrophotometer. Secondary electron micrographs were acquired with a JEOL JSM-7800FLV Scanning Electron Microscope after specimens were prepared onto double sided conductive carbon tape and gold sputter-coated.

3. Results and discussion

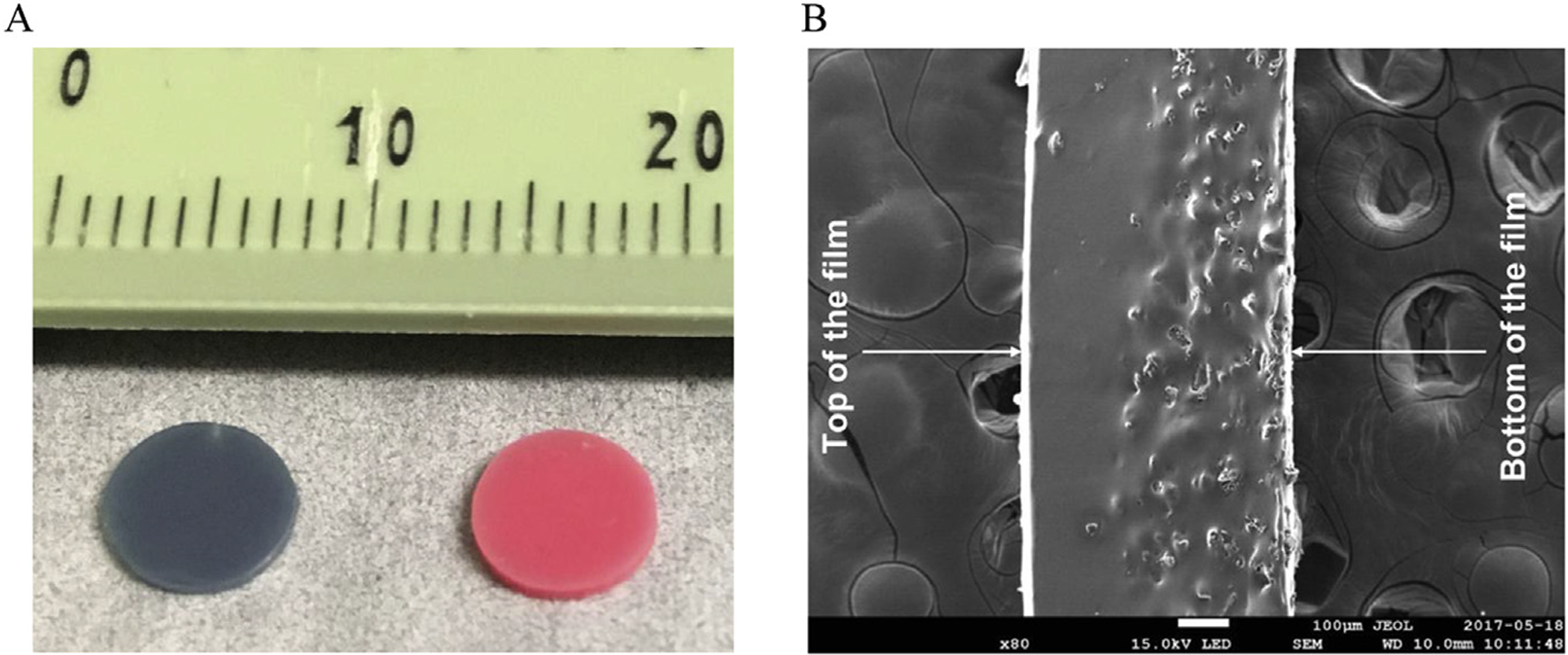

To test the feasibility of the light-induced controlled iNO release approach, a simple system where inert N2 was swept over the RSNO-loaded silicone rubber films was employed (Fig. 1). The NO reservoir for this iNO system was fabricated by blending the RSNO species within PDMS polymer films, allowing for direct modulation of the amount of RSNO incorporated. Narrow band LED light sources were used to initiate the release of NO into the gas phase, and the NO concentration in this phase was measured using an electrochemical NO sensor (Fig. 2). The films were prepared in a manner that resulted in an asymmetric membrane, due to gravity induced settling of the RSNO particles during the polymer curing process that results in the solid RSNO species concentrated towards one side of the film (Fig. 3B), which was oriented away from the gas stream. This provides good protection against possible aerosol formation of the NO donor particles by the flowing N2 stream.

Fig. 3.

(A) Image of PDMS-SNAP (left) and PDMS-GSNO (right) films and (B) secondary electron micrograph from the cross-section of the PDMS-SNAP film.

The NO release kinetics were measured first with PDMS-SNAP samples placed directly onto the bottom of the glass photolysis cell. However, in this case, spikes were observed on the NO release curves resulting from formation and escape of tiny NO gas bubbles accumulated between the silicone rubber film and the surface of the photolysis cell where the sample film was resting upon (Fig. S2). To avoid this artifact, a MicroCloth was placed at the bottom of the cell and the PDMS-SNAP test pieces were placed on top of the MicroCloth. Thus, the released NO gas could easily diffuse out from the film between the micro structured surface and the film.

In order to compare the release kinetics from the NO donor-doped films using the different light sources, NO release experiments were performed at 51 mW/cm2 optical power density. Of note, the reported optical power values were not measured inside the cell where the NO releasing films were placed, but behind the wall of the borosilicate cell. Thus, the actual optical power density reaching the samples is likely somewhat higher than the reported values. Nevertheless, measuring the optical power density provided a means to compare the effect of light intensity on the NO release behavior. The output spectra of the light sources employed are shown in Fig. S3 (Supplemental File).

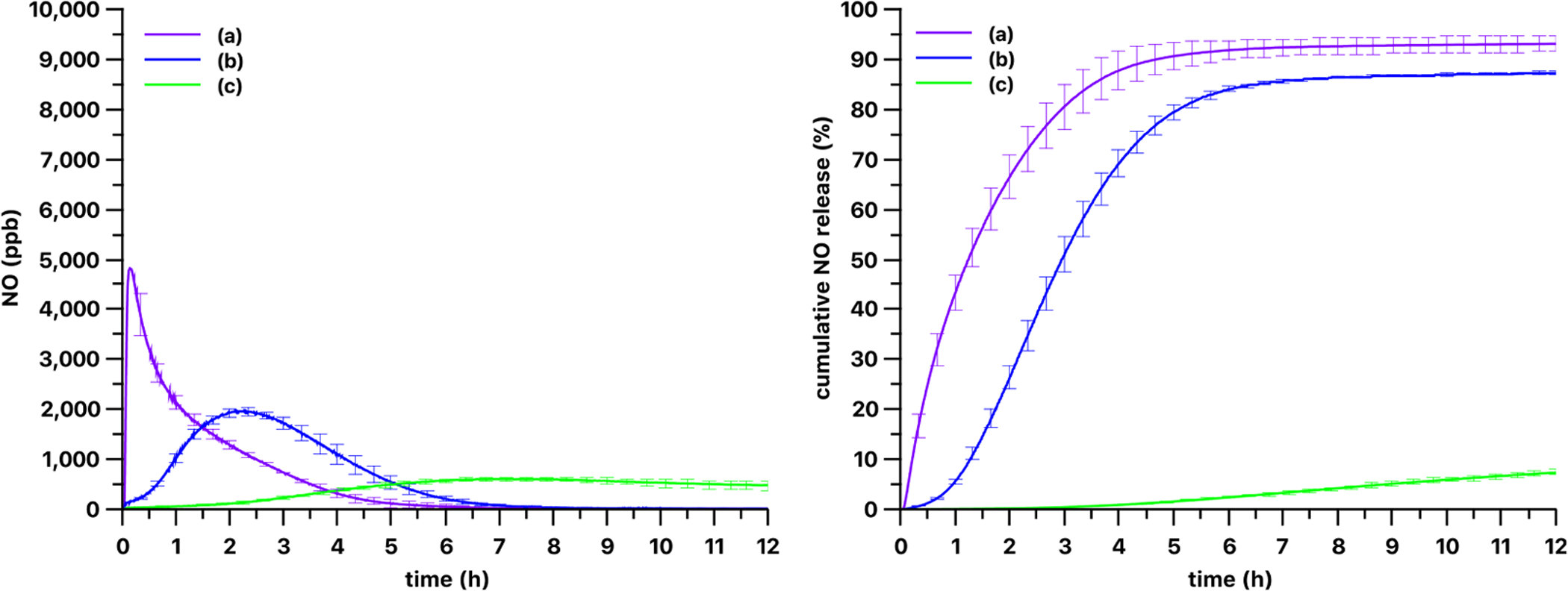

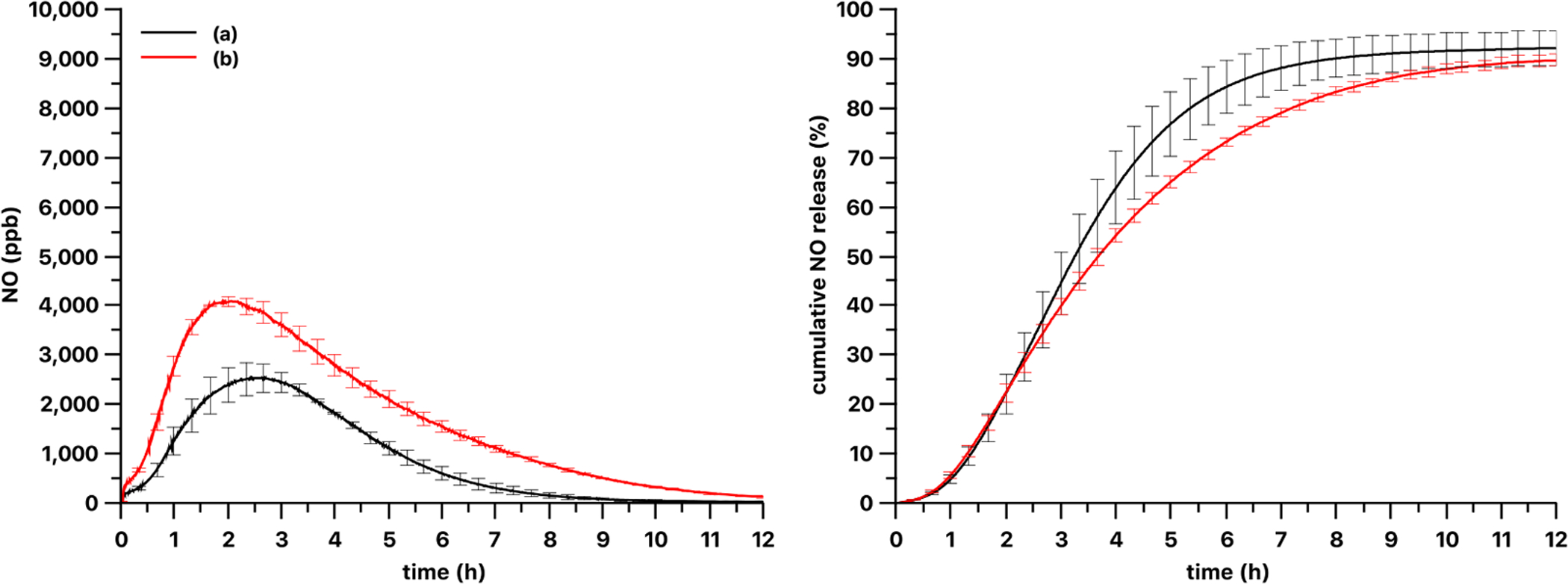

As shown in Figs. 4 and 5, three different LED light sources with varying nominal wavelengths triggered very different NO release patterns from the silicone films. The most efficient light source, in terms of NO release rate from the PDMS-SNAP and PDMS-GSNO films, was the M385LP1 LED with a 385 nm nominal wavelength. The slowest NO release rate from the PDMS-SNAP films occurred when using the M565L3 LED light source with a 565 nm nominal wavelength. NO release from PDMS-GSNO films was typically faster than from the PDMS-SNAP films with all of the light sources tested (Fig. 6). PDMS-GSNO films exhibited significantly faster NO emission when exposed to the 565 nm light source compared to the PDMS-SNAP films.

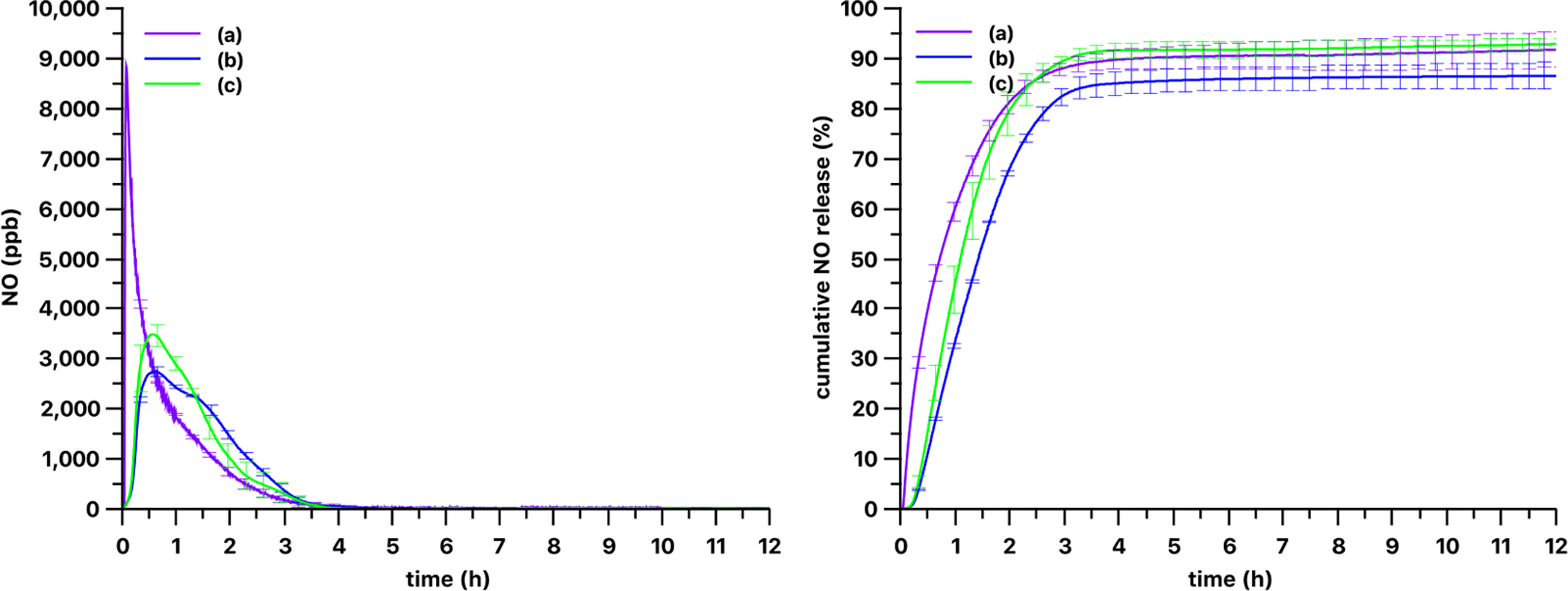

Fig. 4.

Kinetics of gas phase NO levels (left) and cumulative NO release (right) from 3 mm diameter 13 wt% PDMS-SNAP films using (a) 385 nm, (b) 470 nm and (c) 565 nm LED light sources. The optical power was set to 51 mW/cm2 for each light source. Curves show the mean values and the error bars correspond to the standard error of the mean of three parallel measurements.

Fig. 5.

Kinetics of gas phase NO levels (left) and cumulative NO release (right) from 3 mm diameter 13 wt% PDMS-GSNO films using (a) 385 nm, (b) 470 nm and (c) 565 nm LED light sources. The optical power was set to 51 mW/cm2 for each light source. Curves show the mean values and the error bars correspond to the standard error of the mean of three parallel measurements.

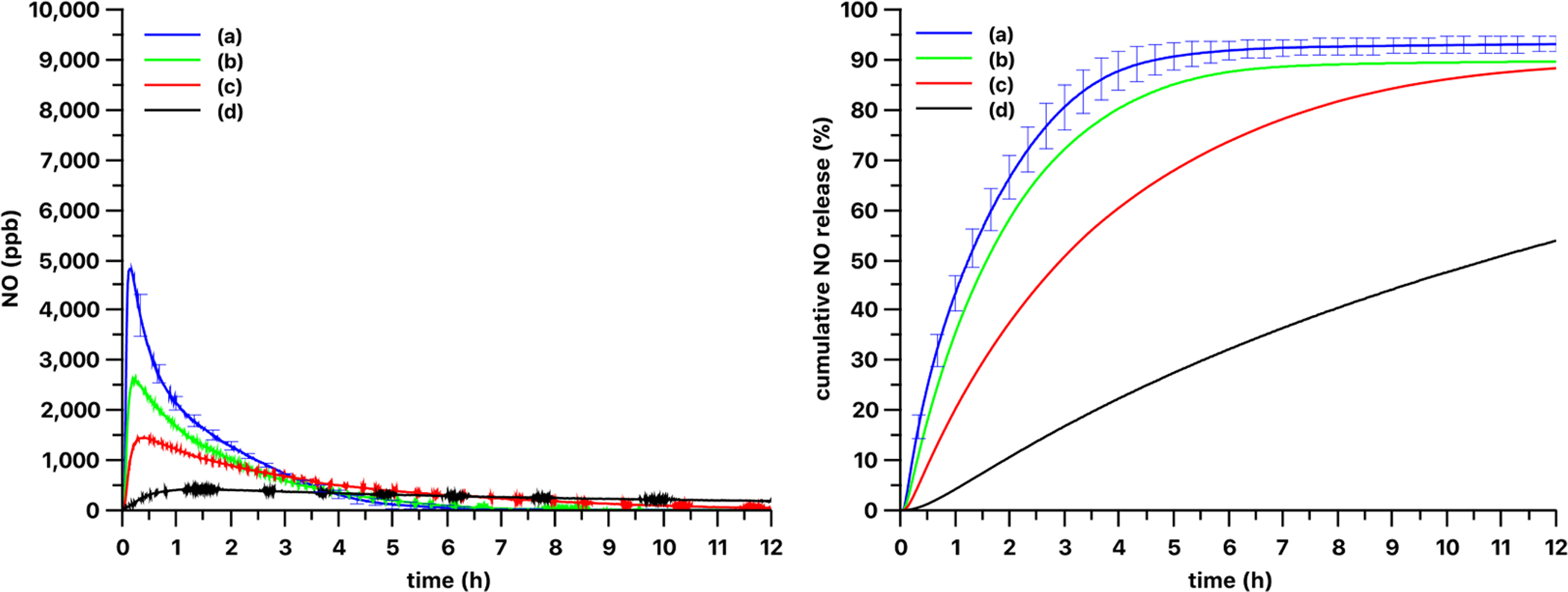

Fig. 6.

Optical power density dependence of release kinetics from 3 mm diameter 13% PDMS-SNAP films with 385 nm light source. The release kinetics of the 13 wt% loaded PDMS-SNAP film were measured at (a) 51, (b) 25, (c) 13 and (d) 5 mW/cm2 optical power densities. Curve and error bars represented mean ± SEM (n = 3) for (a) and single replicates shown for (b)-(d).

The absorbance maximum of RSNOs is at approx. 340 nm (see Fig. S1 in Supporting Information file). Therefore, it would seem reasonable to apply an LED with 340 nm nominal wavelength for photo release; however, deep UV LEDs typically have a lower output power and a shorter lifetime. The specified output power of the M340L4 LED with 340 nm nominal wavelength was more than 30-times less (60 mW vs. 1830 mW) and its life time was more than 13-times less (> 3000 h vs. 40,000 h) as compared to the M385LP1 LED with 385 nm nominal wavelength (for LED spectrum and specifications see Fig. S3 and Table S1 in Supporting Information file). The 340 nm LED was not able to emit at 51 mW/cm2 optical power density when we performed a comparison of the different light sources. The maximal achievable optical power density of the 340 nm deep UV LED was 5 mW/cm2, which induced NO release of only approximately 30% of the total loading of the 13 wt% loaded film in 12 h (data not shown). Thus, the 340 nm light source has practically no relevance for use in obtaining the levels of NO required for therapeutic iNO applications.

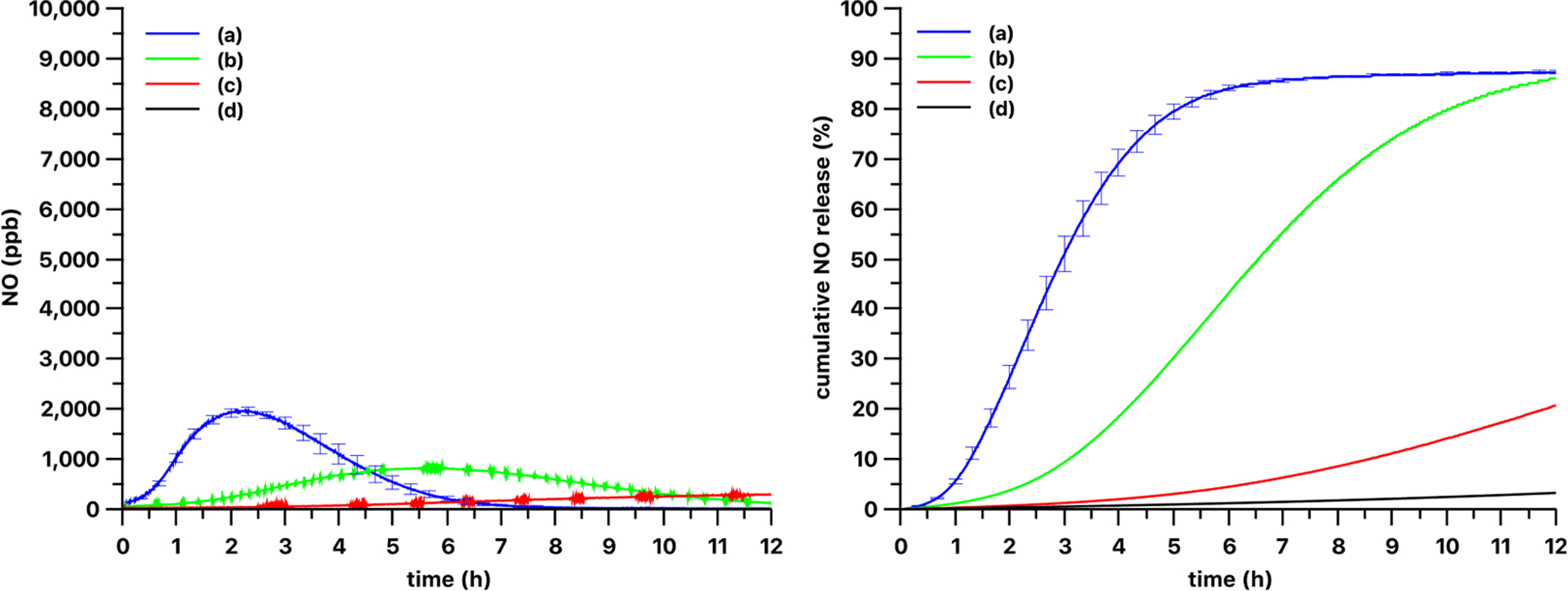

The optical power density dependence on the NO release kinetics from the 13 wt% loaded PDMS-SNAP films are shown on Fig. 6. The optical power density dependence was examined with both the 385 nm and 470 nm LED light sources. As expected, lower optical power densities yielded slower release kinetics. Using the 385 nm LED at 51 mW/cm2 and at 25 mW/cm2 about 80% of the total NO loaded in the films was released in 3 h and 4 h (Fig. 6), respectively. At 13 mW/cm2 optical power density 80% release was achieved after 7.5 h, and use of 5 mW/cm2 density yielded only 54% release in 12 h. Using the 470 nm LED (Fig. 7) 80% release was observed in almost 5 h with 51 mW/cm2 optical power density, and in 10 h with 25 mW/cm2 density. The use of 13 mW/cm2 and 5 mW/cm2 powers yielded only 21% and 3% release respectively in 12 h. Also, obvious differences in the NO release kinetics were observed with these two light sources. Decreasing the light power density of the 385 nm LED source did not result in a time release curve similar in shape to the one measured with the 470 nm light source. Although, the shape of the curves is different, all the curves have a typical induction period followed by an increasing and then a decreasing NO production phase. We speculate that these phases are associated with the amount of thiyl radicals formed which have low mobility in the solid phase. Therefore, the recombination of the thiyl radicals into a disulfide is hindered, while recombination of mobile NO and immobile thiyl radicals is possible. The rate of this latter reaction in the solid phase depends on the actual local concentrations of the species. Also, the 385 nm and 470 nm light sources have different penetration depths into the films (see absorption spectra of RSNOs in Fig. 9 and Fig. S1). Thus, early on, the 385 nm light can induce the photolysis of the RSNO only at the surface of the film. Later, due to the lower absorption of the decomposition product at 385 nm wavelength (see Fig. 9), this front can move gradually deeper into the film over time. The thiyl radicals are generated only in a thin layer within the film, and thus the possibility of their recombination with the NO is low. In contrast, when using the 470 nm light, it can penetrate deeper into the film and generate the thiyl radicals in the whole volume of the film and thus the possibility/rate of the recombination of thiyl radicals and NO is higher. This speculation will need further confirmation via future experiments.

Fig. 7.

Optical power density dependence of release kinetics from 3 mm diameter 13 wt% PDMS-SNAP films with 470 nm light source. The release kinetics were measured at (a) 51, (b) 25, (c) 13 and (d) 5 mW/cm2 optical power densities. Curve and error bars represented mean ± SEM (n = 3) for (a) and single replicates shown for (b)-(d).

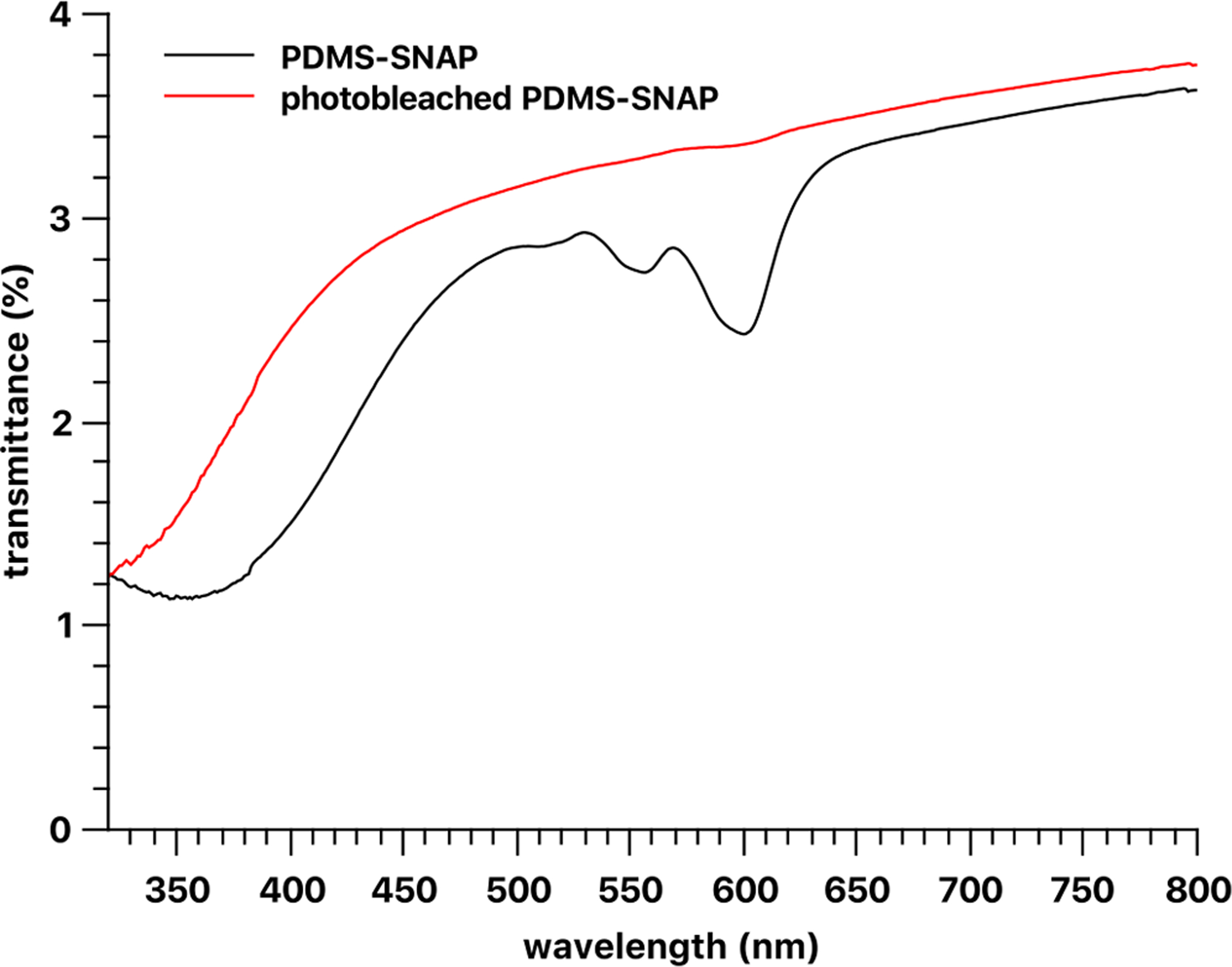

Fig. 9.

Transmittance of PDMS-SNAP and photo bleached 5 wt% PDMS-SNAP films prepared with 120–245 μm size fraction of SNAP crystals. The nominal thickness of the film was 1 mm.

Using a PDMS-SNAP film with a lower loading of 5 wt%, the amount of NO released was decreased as expected (Fig. 8), but the loading did not affect significantly the extent of NO released (92 ± 3% of loaded NO as SNAP) vs. the 13 wt% loaded film (90 ± 1% of loaded NO as SNAP) over the 12 h test period.

Fig. 8.

NO release kinetics and release curve of 6 mm diameter (a) 5% and (b) 13 wt% PDMS-SNAP films using 470 nm LED at 51 mW/cm2 optical power density. Curves show the mean values and the error bars correspond to the standard error of the mean of three parallel measurements.

The originally dark green PDMS-SNAP films became faded green and the originally pink PDMS-GSNO films turned faded pink (almost white) after the 12 h test period due to photo-bleaching at the highest optical power density.

The release curves suggested that the NO release was not complete in 12 h and that about 10% of the original RSNO species was somehow unavailable for photorelease. The SNAP-doped PDMS films showed very low transmittance, and it remained low even after photo-bleaching (Fig. 9) of the film. Indeed, the absorbance peaks at ~340 nm and ~580 nm associated with the NO donor absorbance peaks disappeared, and another band appeared in the lower wavelength range. Thus, fewer photons likely reached the inner part of the film, and even after most of the NO is released, the light intensity inside the film and/or in the core of the SNAP crystals was insufficient for complete release of the payload.

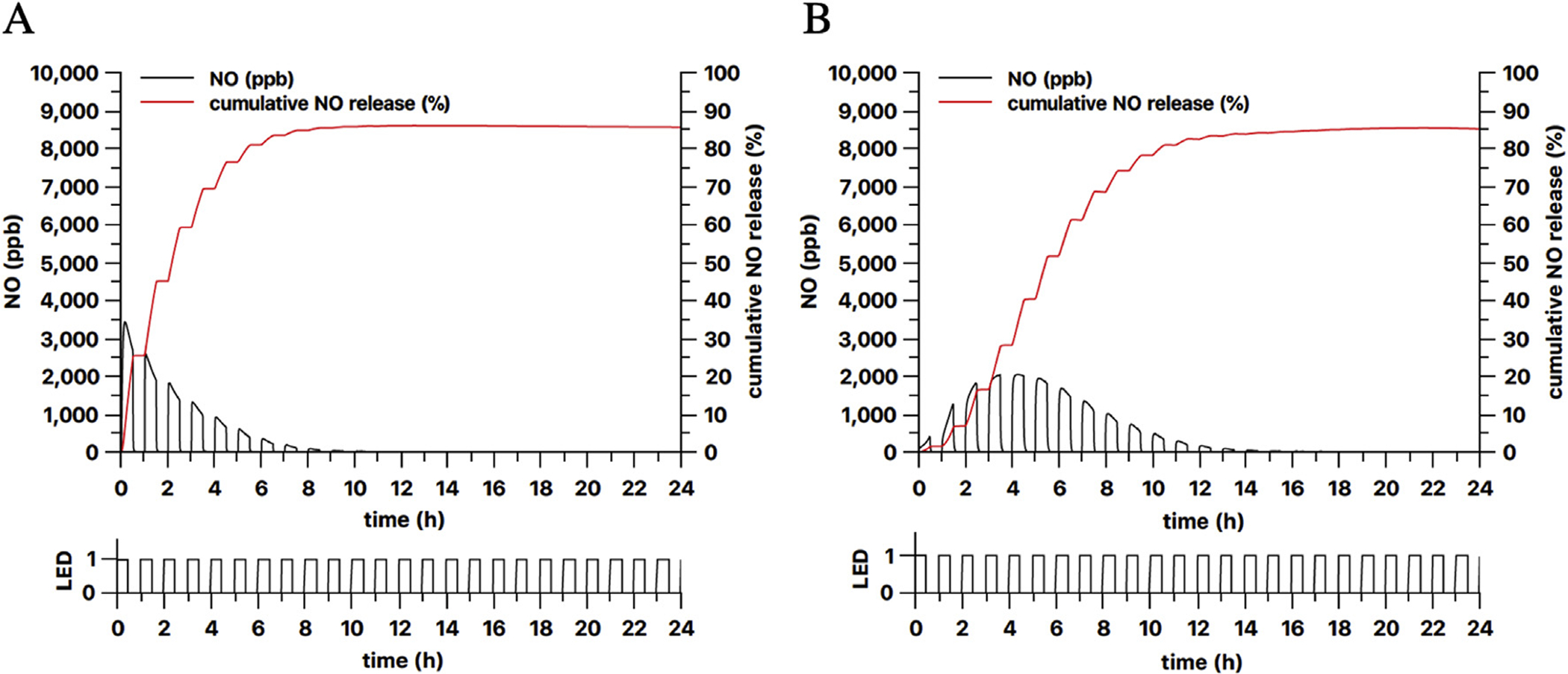

It is also possible to modulate the NO release by turning on and off the LED light source periodically (Fig. 10). Interestingly, this modulation did not seem to affect the overall NO release kinetics. If the periods with the light off would be removed from the curves, they would be almost the same curves measured without the modulation.

Fig. 10.

Modulation of NO release from 3 mm diameter 13 wt% PDMS-SNAP films by turning on and off the (A) 385 nm and (B) 470 nm LED light source every 30 min. LED shows the ON/OFF schedule of the light source (1 = ON, 0 = OFF).

To date, the use of SNAP or GSNO doped PDMS for gas phase delivery of NO has not been reported previously in the literature. The primary role of the silicone matrix is to avoid the aerosol formation of NO donor in the gas stream, while posing minimal barrier for permeation of NO gas through it [27]. In previous studies, SNAP was covalently linked to the polymer chain and a flood light [22] or 470 nm LED [23] was used to obtain NO release into an aqueous phase. In this work, RSNO is doped in solid, microcrystalline form into the polymer (Fig. 3). We chose to load the RSNO into the PDMS film by blending the microcrystalline NO donor into the two-component PDMS before curing, since this method enables better control of the NO donor loading within the films, over a wider weight percent range. Also, this method is compatible with the GSNO. Impregnation/swelling of silicone rubber with 125 mg/mL SNAP dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF) [26] can result 5.4 wt% loading, although the achievable loading is limited by the solubility of SNAP in the organic solvent and the swelling properties. Another important benefit of the present blending method is that the SNAP is never dissolved during the film preparation process. Thus, there is a less risk that the SNAP can decompose during the polymer preparation. Indeed, the impregnation/swelling method can result in smaller SNAP microcrystals in the silicone matrix. However, we did not observe any significant effect of SNAP particle size (comparing size fractions of 63–120 μm and 120–260 μm diameter) on the release kinetics using the method of film preparation employed here (data not shown).

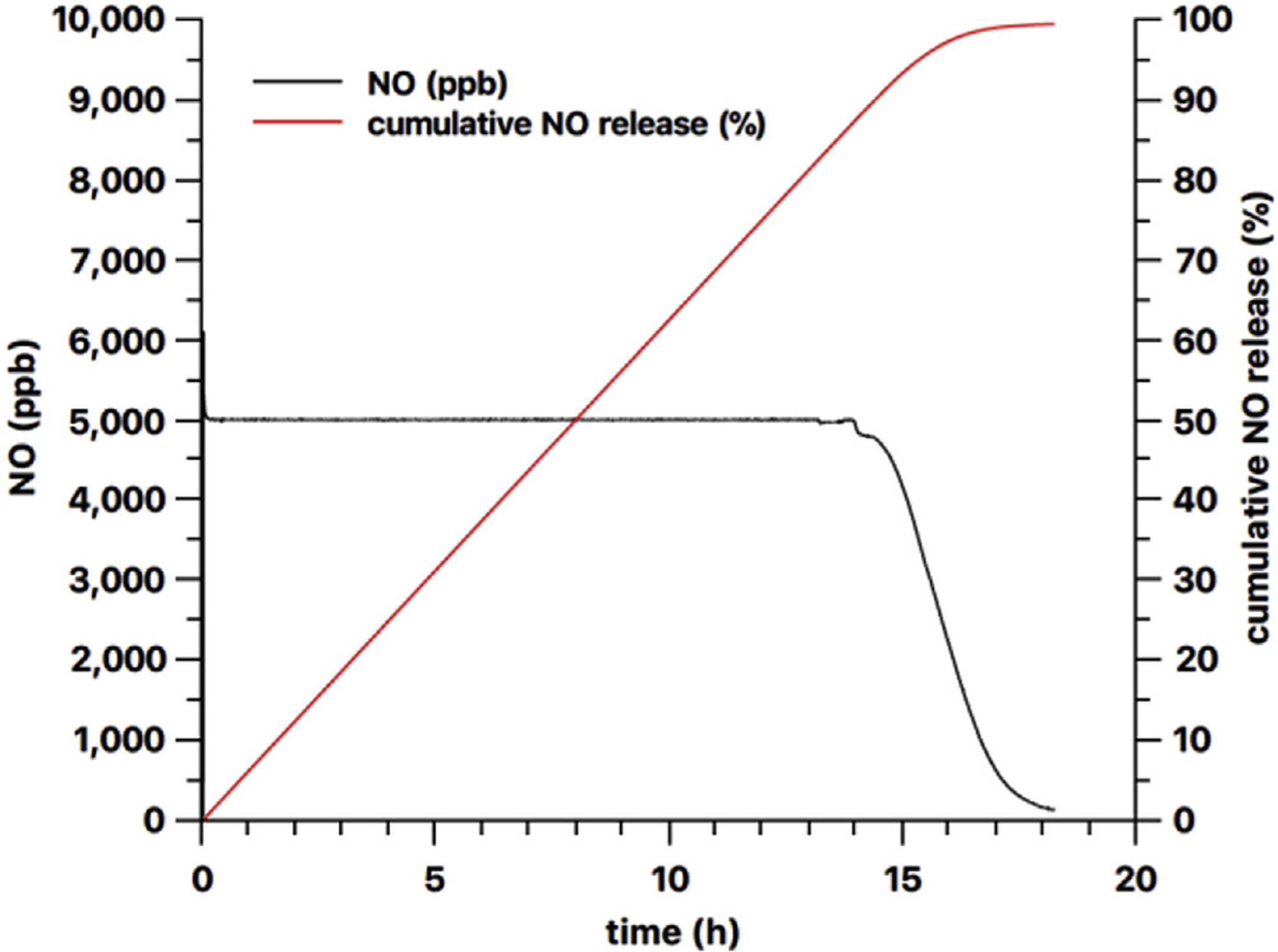

These results demonstrate that the kinetics of the light induced NO release from SNAP and GSNO are wavelength dependent and the initial release kinetics is faster in case of the lower wavelengths associated with the absorption maxima at around 340 nm (1(n,π*)) of RSNO molecules. The release kinetics can be modulated via the intensity of the light employed. However, when using a constant light intensity, it is not possible to obtain a stable NO release into the gas phase. Thus, to achieve constant NO levels in the recipient gas stream, it will be necessary to use an NO sensor to monitor levels of the gas phase NO, and thereby provide feedback control of the power of the light source to achieve a desired constant level of NO in the N2 stream.

Our initial results towards achieving this goal are shown in Fig. 11, which demonstrates the feasibility to use RSNO silicone rubber films to create a constant level of NO, via feedback-controlled modulation of the light intensity, for more than 12 h. Our future studies will include optimization of this photo-release NO generation system that includes the stable RSNO-PDMS polymer (NO reservoir) described here combined with the NO sensor-based feedback control that will allow for constant and controlled NO generation from this compact and portable system.

Fig. 11.

Feedback controlled NO release from a 9 mm diameter 59 mg 13 wt% PDMS-SNAP film using the 385 nm LED light source.

4. Conclusion

Blending RSNO-type NO donor molecules within silicone rubber films is a viable method for preparing a stable NO reservoir and photo-release NO gas phase delivery system for potential use in iNO applications. In contrast to the recently reported solvent swelling that can impregnate silicone rubber with SNAP but is limited by the solubility of the SNAP and swelling of the polymer, the RSNO doping method reported here enables doping both of GSNO and SNAP and allows precise control over the polymer fabrication in terms of the wt% RSNO incorporation. Among the tested LED light sources, a 565 nm LED is the least effective in terms of NO release in case of PDMS-SNAP films, but quite effective in case of the PDMS-GSNO films. The 385 nm LED induces a rapid release of the NO from both PDMS-SNAP and PDMS-GSNO films, while the 470 nm LED produces a more sustained release. However, none of these light sources induces a steady, constant emission rate of NO from the RSNO-doped silicone rubber film into the gas phase. To achieve a stable zero order like NO release into the carrier stream gas flow above the NO donor doped film, the continuous modulation of the light intensity of the LED source is necessary. This can only be achieved using feedback control based on measured NO levels in the recipient gas stream using an NO selective sensor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R21 EB024038-02 and HL127981. The authors would like to thank Karl F. Olsen, Rose Ackermann and Cameron Nobile for their general technical assistance and Roy F. Wentz for preparing speciality glassware.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2019.01.016.

References

- [1].Griffiths MJD, Evans TW, Inhaled nitric oxide therapy in adults, N. Engl. J. Med 353 (2005) 2683–2695, 10.1056/NEJMra051884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Szabo C, Gaseotransmitters: new frontiers for translational science, Sci. Transl. Med 2 (2010), 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000721 59ps54–59ps54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wo Y, Brisbois EJ, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME, Recent advances in thromboresistant and antimicrobial polymers for biomedical applications: just say yes to nitric oxide (NO), Biomater. Sci 4 (2016) 1161–1183, 10.1039/C6BM00271D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bloch KD, Ichinose F, Roberts JD, Zapol WM, Inhaled NO as a therapeutic agent, Cardiovasc. Res 75 (2007) 339–348, 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Deppisch C, Herrmann G, Graepler-Mainka U, Wirtz H, Heyder S, Engel C, Marschal M, Miller CC, Riethmüller J, Gaseous nitric oxide to treat antibiotic resistant bacterial and fungal lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis: a phase I clinical study, Infection 44 (2016) 513–520, 10.1007/s15010-016-0879-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Miller CC, Hergott CA, Rohan M, Arsenault-Mehta K, Döring G, Mehta S, Inhaled nitric oxide decreases the bacterial load in a rat model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia, J. Cyst. Fibros 12 (2013) 817–820, 10.1016/j.jcf.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yaacoby-Bianu K, Gur M, Toukan Y, Nir V, Hakim F, Geffen Y, Bentur L, Compassionate nitric oxide adjuvant treatment of persistent Mycobacterium infection in cystic fibrosis patients, Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J (2017) 1, 10.1097/INF.0000000000001780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Howlin RP, Cathie K, Hall-Stoodley L, Cornelius V, Duignan C, Allan RN, Fernandez BO, Barraud N, Bruce KD, Jefferies J, Kelso M, Kjelleberg S, Rice SA, Rogers GB, Pink S, Smith C, Sukhtankar PS, Salib R, Legg J, Carroll M, Daniels T, Feelisch M, Stoodley P, Clarke SC, Connett G, Faust SN, Webb JS, Low-dose nitric oxide as targeted anti-biofilm adjunctive therapy to treat chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis, Mol. Ther 25 (2017) 2104–2116, 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chandrasekharan P, Kozielski R, Kumar V, Rawat M, Manja V, Ma C, Lakshminrusimha S, Early use of inhaled nitric oxide in preterm infants: is there a rationale for selective approach? Am. J. Perinatol 34 (2016) 428–440, 10.1055/s-0036-1592346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ren H, Wu J, Xi C, Lehnert N, Major T, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME, Electrochemically modulated nitric oxide (NO) releasing biomedical devices via copper(II)-Tri(2-pyridylmethyl)amine mediated reduction of nitrite, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6 (2014) 3779–3783, 10.1021/am406066a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Qin Y, Zajda J, Brisbois EJ, Ren H, Toomasian JM, Major TC, Rojas-Pena A, Carr B, Johnson T, Haft JW, Bartlett RH, Hunt AP, Lehnert N, Meyerhoff ME, Portable nitric oxide (NO) generator based on electrochemical reduction of nitrite for potential applications in inhaled NO therapy and cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, Mol. Pharm 14 (2017) 3762–3771, 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Williams DLH, Nitric oxide release from S-nitrosothiols (RSNO) - the role of copper ions, Transit. Met. Chem 21 (1996) 189–191, 10.1007/BF00136555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chipinda I, Simoyi RH, Formation and stability of a nitric oxide donor: S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine, J. Phys. Chem. B 110 (2006) 5052–5061, 10.1021/jp0531107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wood PD, Mutus B, Redmond RW, The mechanism of photochemical release of nitric oxide from S-nitrosoglutathione, Photochem. Photobiol 64 (1996) 518–524, 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb03099.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brisbois EJ, Handa H, Major TC, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME, Long-term nitric oxide release and elevated temperature stability with S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP)-doped Elast-eon E2As polymer, Biomaterials 34 (2013) 6957–6966, 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brisbois EJ, Davis RP, Jones AM, Major TC, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME, Handa H, Reduction in thrombosis and bacterial adhesion with 7 day implantation of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP)-doped Elast-eon E2As catheters in sheep, J. Mater. Chem. B 3 (2015) 1639–1645, 10.1039/C4TB01839G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wo Y, Li Z, Brisbois EJ, Colletta A, Wu J, Major TC, Xi C, Bartlett RH, Matzger AJ, Meyerhoff ME, Origin of long-term storage stability and nitric oxide release behavior of CarboSil polymer doped with S -nitroso- N -acetyl- d-penicillamine, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7 (2015) 22218–22227, 10.1021/acsami.5b07501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wolf AK, Qin Y, Major TC, Meyerhoff ME, Improved thromboresistance and analytical performance of intravascular amperometric glucose sensors using optimized nitric oxide release coatings, Chin. Chem. Lett 26 (2015) 464–468, 10.1016/j.cclet.2015.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pant J, Goudie MJ, Hopkins SP, Brisbois EJ, Handa H, Tunable nitric oxide release from S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine via catalytic copper nanoparticles for biomedical applications, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces (2017), 10.1021/acsami.7b01408 acsami.7b01408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].El Kasmi KC, Qualls JE, Pesce JT, Smith AM, Thompson RW, Henao-Tamayo M, Basaraba RJ, König T, Schleicher U, Koo M-S, Kaplan G, Fitzgerald KA, Tuomanen EI, Orme IM, Kanneganti T-D, Bogdan C, Wynn TA, Murray PJ, Toll-like receptor–induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens, Nat. Immunol 9 (2008) 1399–1406, 10.1038/ni.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Marazzi M, Lo A, Angel M, Frutos LM, Temprado M, Modulating nitric oxide release by S -nitrosothiol photocleavage: mechanism and substituent effects, J. Phys. Chem 116 (2012) 7039–7049, 10.1021/jp304707n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Frost MC, Meyerhoff ME, Controlled photoinitiated release of nitric oxide from polymer films containing S -nitroso- N -acetyl- dl -penicillamine derivatized fumed silica filler, J. Am. Chem. Soc 126 (2004) 1348–1349, 10.1021/ja039466i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gierke GE, Nielsen M, Frost MC, Science and Technology of Advanced Materials S-Nitroso-N-acetyl-D-penicillamine covalently linked to polydimethylsiloxane (SNAP–PDMS) for use as a controlled photoinitiated nitric oxide release polymer, Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater 12 (2011), 10.1088/1468-6996/12/5/055007 55007–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lautner G, Schwendeman SP, Meyerhoff ME, Nitric oxide releasing PLGA microspheres for biomedical applications, NSTI Adv. Mater. - TechConnect Briefs, 2015 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hart TW, Some observations concerning the S-nitroso and S-phenylsulphonyl derivatives of L-cysteine and glutathione, Tetrahedron Lett. 26 (1985) 2013–2016, 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)98368-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Colletta A, Wu J, Wo Y, Kappler M, Chen H, Xi C, Meyerhoff ME, S -Nitroso- N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) Impregnated silicone foley catheters: a potential biomaterial/device to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng (2015), 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00032 150508100821005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Robb WL, Thin silicone membranes–their permeation properties and some applications, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 146 (1968) 119–137, 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb20277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.