Abstract

Objectives:

Evaluation of bite force one, two, and four weeks after discharge following treatment of Le Fort I and/or Le Fort II fracture by rigid fixation and mandibulomaxillary fixation.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to evaluate bite force following treatment of Le Fort I and/or Le Fort II fractures by rigid fixation and mandibulomaxillary fixation at one, two, and four weeks after discharge. This provides valuable results to guide the development of a treatment protocol for Le Fort fractures.

Method:

This was a prospective study including 31 patients who underwent followup examination three times after being discharged from hospital. The examination evaluated bite force using a bite force meter in the right molar, left molar, and incisor regions.

Results:

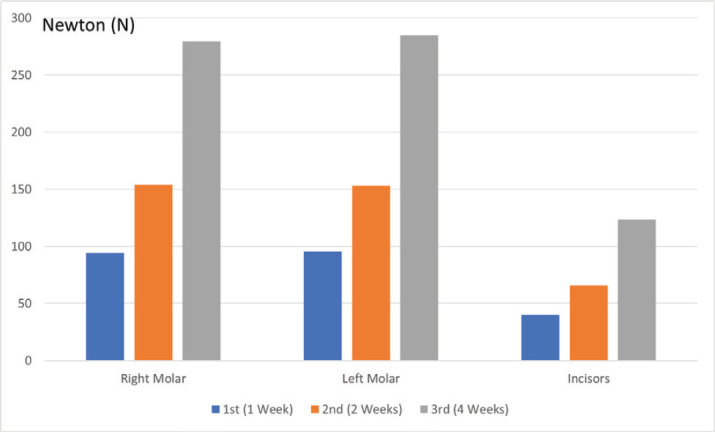

One week after discharge, bite forces in the right molar, left molar, and incisor regions were 94.29 ± 58.80 N, 95.42 ± 57.34 N, and 39,94 ± 30,29 N, respectively. Two weeks after discharge, bite forces in the right molar, left molar, and incisor regions were 153.84 ± 89.14 N, 153.00 ± 78.55 N, and 65,9 ± 43.89 N, respectively. Four weeks after discharge, bite forces in the right molar, left molar, and incisor regions were 279.77 ± 95.46 N, 285.00 ± 90,47 N, and 123.42 ± 54.04 N, respectively.

Conclusions:

Bite forces in the right molar, left molar, and incisor regions were significantly increased one week, two weeks, and four weeks after discharge. Bite force may be a helpful parameter to confirm the stability of the midface bone after treatment of Le Fort fractures.

Keywords: bite force, bite force after trauma, Le Fort, maxillary bone, midface, mandibulomaxillary fixation, rigid fixation

1. BACKGROUND

According to Phillips et al., there were 1132 cases (16%) diagnosed with Le Fort I fractured and 1305 (19%) Le Fort II fractures in 6989 Le Fort fractures (1). Because traffic accidents are becoming more and more complex, there is an increasing number of both Le Fort I and Le Fort II fracture cases, and maxillary fracture cases as a whole. Furthermore, midfacial fractures have complicated clinical characteristics, causing severe deformations after the injury, resulting in sequelae such as malocclusion, convex face, displaced eyeballs, or nerve injury (2,3). Therefore, it is essential to study the clinical characteristics of these fractures in order to properly and accurately evaluate them and provide an optimal treatment regime.

According to Takaki et al., who evaluated the maximum bite force in 100 Brazilians aged 11–60 with healthy natural teeth, the mean maximum bite force was 285.01 N in men and 253.99 N in women (4). In a previous study by Varga et al. on 60 Caucasian subjects with a neutral occlusion, thirty subjects (15 males and 15 females) were aged 15 years and 30 (14 males and 16 females). It is noted that 18 years were recorded maximum bite forces ranging from 118 N to 922 N, with a mean of 777.7 ± 78.7 in males and 481.6 ±190.42 N in females (5). In addition to the bite force generated by healthy teeth, there are also studies on bite force in subjects wearing full-mouth removable dentures, in whom the bite force was decreased to 20–40% of the normal value (146.3–149.1 N) after 6 months of adaptation to the denture (6). Bite force was recorded on prosthetics on dental implants was 172.5 ± 42.1 N (7) .

Open reduction with internal fixation using plates and screws enhances the stability and correction of anatomic structures, as well as greatly recovering bite force and function. However, in some cases, such as severe comminuted fractures, mandibulomaxillary fixation could help with midface immobilization after inadequate internal fixation.

Figure 1. Bite force meter manufactured by the research team at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ho Chi Minh City.

2. OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study was to evaluate bite force following treatment of Le Fort I and/or Le Fort II fractures by rigid fixation and mandibulomaxillary fixation at one, two, and four weeks after discharge. This provides valuable results to guide the development of a treatment protocol for Le Fort fractures.

3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study included 31 patients with Le Fort I or Le Fort II fractures at the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery, National Hospital of Odonto-Stomatology in Ho Chi Minh City from August 2019 to June 2020. Patients with collapsed bones or fractures with large defect areas, patients with unidentifiable intercuspation position due to tooth loss, or patients who had previously been treated for Le Fort I or Le Fort II fractures at other healthcare facilities were all excluded from this study. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Biomedicine Study of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (No. 19389 – ĐHYD).

All patients were subjected to clinical examination, photographic assessment, and radiological examinations (CT scan and 3D views). All 31 patients who fulfilled the selection criteria underwent internal fixation, using at least zygomaticomaxillary buttresses with some cases could not be bone grafting, such as severely comminuted fractures at the nasomaxillary buttress or nasofrontal buttresses. After the osteosynthesis, they underwent mandibulomaxillary fixation.

This was a prospective study that was conducted with three postoperative examinations at one, two, and four weeks after discharge. Bite force was evaluated with the patient seated in a straight head and back posture, and not leaning back against the wall. The Patient bit the bite force measurement device sensor at the central incisor region and first molar region for 3–4 seconds, with the occlusal plane parallel to the floor (7). This procedure was repeated three times and the mean values were calculated and recorded (8). The bite force meter was manufactured in-house by the research team of the Faculty of Odonto-Stomatology at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ho Chi Minh City.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 20.0. Means and standard deviations were calculated for all variables. Comparative statistical analysis was conducted using paired ttests. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant if p ≤ 0.05.

4. RESULTS

The mean bite force of the 31 patients at the first follow-up visit (after one week) was recorded and the largest value was recorded after three measurements from each patient. The bite forces were 94.29 ± 58.80 N, 95.42 ± 57.34 N, and 39.94 ± 30.29 N at the right molar, left molar, and incisor positions, respectively. The maximum bite forces were 220 N, 230 N, and 155 N, respectively. The minimum bite forces were 30 N, 38 N, 15 N, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Bite forces at first follow-up visit after discharge (one week).

| Bite force (N) | Quantity (n) | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right molar | 31 | 30.0 | 220.0 | 94.290 | 58.801 |

| Left molar | 31 | 38.0 | 230.0 | 95.419 | 57.339 |

| Incisor | 31 | 15.0 | 155.0 | 39.935 | 30.294 |

After two weeks, the mean bite forces recorded at the right molar, left molar, and incisor positions were 153.84 ± 89.14 N, 153 ± 78.55 N, and 65.9 ± 43.89 N, respectively. The maximum bite forces were 365 N, 310 N, and 177 N, respectively. The minimum bite forces were 55 N, 50 N, and 16 N, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Bite forces at second follow-up visit after discharge (two weeks).

| Bite force (N) | Quantity (n) | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right molar | 31 | 55.0 | 365.0 | 153.839 | 89.1359 |

| Left molar | 31 | 50.0 | 310.0 | 153.000 | 78.5460 |

| Incisor | 31 | 16.0 | 177.0 | 65.903 | 43.8850 |

After four weeks, the mean bite forces at the right molar, left molar, and incisor positions were 279.77 ± 95.46 N, 285 ± 90.47 N, and 123.42 ± 54.04 N, respectively. The maximum bite forces were 420 N, 415 N, and 230 N, respectively. The minimum bite forces were 80 N, 90 N, and 22 N, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Bite forces at third follow-up visit after discharge (four weeks).

| Bite force (N) | Quantity (n) | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right molar | 31 | 80.0 | 420.0 | 279.774 | 95.4574 |

| Left molar | 31 | 90.0 | 415.0 | 285.000 | 90.4721 |

| Incisor | 31 | 22.0 | 230.0 | 123.419 | 54.0363 |

The bite forces at all three positions increased markedly over time, and these differences were statistically significant (Figure 2 and Table 4).

Figure 2. Bite forces at the right and left molar and incisor positions after one, two, and four weeks.

Table 4. Bite forces at the right and left molar and incisor positions after one, two, and four weeks.

| Bite force (N) | 1st follow-up after discharge | 2nd follow-up after discharge | 3rd follow-up after discharge | p (1st vs. 2nd follow-up ) |

p (2nd vs. 3rd follow-up ) |

p (1st vs. 3rd follow-up ) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incisor | Mean | 39.935 | 65.903 | 123.419 | 0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.011 |

| Standard Deviation | 30.2940 | 43.8850 | 54.0363 | ||||

| Right molar | Mean | 94.290 | 153.839 | 279.774 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Standard deviation | 58.8009 | 89.1359 | 95.4574 | ||||

| Left molar | Mean | 95.419 | 153.000 | 285.000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Standard deviation | 57.3392 | 78.5460 | 90.4721 |

5. DISCUSSION

In our study, bite forces were assessed in 31 patients one week, two weeks, and 4 weeks after discharge following treatment for Le Fort I or Le Fort II fractures. Bite force was 94.29 ± 58.8 N at right molar, 95.42 ± 57.54 N at left molar and 39.94 ± 30.29 N at incisor after being recorded one week. Bite force was decreased at one week could be due to examine for the first time, so opening the mouth and moving the opening muscles was difficult and the patients still had pain when biting the jaws together due to ongoing bone and soft tissue healing. Bite force was 153.84 ± 89.14 N at right molar, 153.00 ± 78.55 N at left molar and 65.9 ± 43.89 N at incisor after being recorded two weeks. The bite forces at all three positions were significantly increased compared to the forces at one week. At this time, bone healing was at the stage of calcification of cartilage, and there was initial stabilization (9). After four weeks, the patients’ bite forces increased significantly; at this time the bone healing had entered the third stage, which is bone calcification, and the bone healing was over 70% complete with improved bone and soft tissue stability, and only a minimal effect on bite force. According to Chong et al. (10), the mean bite force of healthy people older than 60 was 420.5 ± 242.0 N and bite forces ranged from 185 to 1200 N, whereas in healthy people aged 18–25, the mean bite force was 541.4 ± 296.3 N. A variety of factors have been reported to alter bite force, including muscle strength, muscle mass, exercise regimen, participation in sports, daily life habits, and jaw mobility (11,12). According to Arnold (13), bite forces are larger in the molar region than in the anterior region because it is closer to the occlusal muscle, and also because these teeth have larger root surface areas. For the bite position of each position, there are also differences, according to Ferrario et al., the bite force in the incisor region is about 40–48% of the bite force in the upper molar region at the healthy people (14). According to Wang et al., with Le Fort I fracture was internal fixation at 2 zygomaticomaxillary sutures and 2 nasomaxillary sutures, bite force is restored to about 90% of normal physiological bite force (15). According to our study, The bite force was 279.77 ± 95.46 N at right molar, 285 ± 90.47 N at left molar and 123.42 ± 54.04 N at incisor after being recorded four weeks. Our results are similar to those of Wang et al., their study was reported bite forces of approximately 200 N in the molar region and approximately 150 N in the incisor region (15). Another study by Spagnol et al. measured bite force after bone healing in patients with Le Fort II fracture, naso-orbital-ethmoid complex, and the frontal bone was 252.12 ± 44.42 N in right molar, and 241.73 ± 60.80 N in left molar (16).

Bite forces represent maxillary bone healing and the restoration of the chewing system. The increase in bite force in our 31 patients demonstrates that treatment with bone fusion and mandibulomaxillary fixation restores a stable bite force and leads to successful healing after one month. Although the sample size in the present study was small and the follow-up duration was short, it can be concluded that by one month after treating Le Fort fractures by internal fixation and mandibulomaxillary fixation, recovery was almost complete. In addition, the variation in bite forces was very large, especially in the first and second weeks after discharge, so, in future studies, it will be necessary to exclude biases such as pain, tissue swelling, and limited opening of the mouth.

6. CONCLUSION

Bite forces in the right molar, left molar, and incisor regions changed markedly over the course of three follow-up examinations at one, two, and four weeks. Bite force may be a helpful parameter to confirm the stability of the midface bone after treatment of Le Fort fractures.

Ethical approval and Declaration of patient consent: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Biomedicine Study of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (No. 19389 – ĐHYD). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study. Privacy and confidentiality of the patient records were adhered to, in managing the clinical information in the conduct of this research.

Author’s contribution:

Doan-Van Ngoc and Le Hoai Phuc contributed equally to this article as co-first authors. Doan-Van Ngoc and Le Hoai Phuc gave a substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis, and data interpretation. Le Hoai Phuc and Nguyen Minh Duc had a part in preparing the article for drafting and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Each author gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflicts of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial support and sponsorship:

Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phillips BJ, Turco LM. Le Fort Fractures: A Collective Review. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2017 Oct;5(4):221–230. doi: 10.18869/acadpub.beat.5.4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendonca D, Kenkere D. Avoiding occlusal derangement in facial fractures: An evidence based approach. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013 May;46(2):215–20. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.118596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrenfeld M, Manson N P, Prein Joachim, eds. , editors. Principles of Internal Fixation of the Craniomaxillofacial Skeleton: Trauma and Orthognathic Surgery. Thieme Medical. 2012:199–201. N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma TP, Kumathalli KI, Jain V, Kumar R. Bite force recording devices–A review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Sep;11(9):ZE01–ZE05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/27379.10450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goiato MC, Zuim PRJ, Moreno A, et al. Does pain in the masseter and anterior temporal muscles influence maximal bite force? Arch Oral Biol. 2017 Nov;83:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2017.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira-Campos GH, Lauriti L, Yamamoto MK, Júnior RC, Luz JG. Trends in Le Fort fractures at a South American trauma care center: Characteristics and management. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2016 Mar;15(1):32–7. doi: 10.1007/s12663-015-0808-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venugopal MG, Sinha R, Menon PS, Chattopadhyay PK, Roy Chowdhury SK. Fractures in the maxillofacial region: A four year retrospective study. Med J Armed Forces India. 2010 Jan;66(1):14–7. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(10)80084-X. Epub 2011 Jul 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tent PA, Juncar RI, Lung T, Juncar M. Midfacial fractures: A retrospective etiological study over a 10-year period in Western Romanian population. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018 Dec;21(12):1570–1575. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_256_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Septa D, Newaskar VP, Agrawal D, Tibra S. Etiology, incidence and patterns of mid-face fractures and associated ocular injuries. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014 Jun;13(2):115–9. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0452-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaleckas L, Pečiulienė V, Gendvilienė I, Pūrienė A, Rimkuvienė J. Prevalence and etiology of midfacial fractures: a study of 799 cases. Medicina (Kaunas) 2015;51(4):222–7. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougherty WM, Christophel JJ, Park SS. Evidence-based medicine in facial trauma. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017 Nov;25(4):629–643. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jagodzinski M, Krettek C. Effect of mechanical stability on fracture healing—an update. Injury. 2007 Mar;38(Suppl 1):S3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsell R, Einhorn TA. The biology of fracture healing. Injury. 2011 Jun;42(6):551–5. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.031. Epub 2011 Apr 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schimmel M, Memedi K, Parga T, Katsoulis J, Müller F. Masticatory performance and maximum bite and lip force depend on the type of prosthesis. Int J Prosthodont. 2017 November/December;30(6):565–572. doi: 10.11607/ijp.5289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bai Z, Gao Z, Xiao X, Zhang W, Fan X, Wang Z. Application of IMF screws to assist internal rigid fixation of jaw fractures: our experiences of 168 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015 Sep 1;8(9):11565–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus JR, Erdmann E, Rodriguez ED. St. Louis, Mo: Quality Medical Pub; 2012. Essentials of Craniomaxillofacial Trauma. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oryan A, Monazzah S, Bigham-Sadegh A. Bone injury and fracture healing biology. Biomed Environ Sci. 2015 Jan;28(1):57–71. doi: 10.3967/bes2015.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]