Abstract

Over 30 years since enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), people with disability continue experiencing health care disparities. The ADA mandates that patients with disability receive reasonable accommodations. In our survey of 714 U.S. physicians in outpatient practices, 35.8 percent reported knowing little or nothing about their legal responsibilities under the ADA, 71.2 percent answered incorrectly about who determines reasonable accommodations, 20.5 percent did not correctly identify who pays for these accommodations, and 68.4 felt that they were at risk of ADA lawsuits. Physicians who felt that lack of formal education or training was a moderate or large barrier to caring for patients with disability were more likely to report little or no knowledge of their responsibilities under the law and were more likely to believe they were at risk of an ADA lawsuit. To achieve equitable care and social justice for patients with disability, considerable improvements are needed to educate physicians and make health care delivery systems more accessible and accommodating.

Keywords: disabled persons, disability, health equity, physicians, Americans with Disabilities Act, accommodations

Introduction

Reducing barriers to equitable health care is a professional imperative for physicians.1 However, achieving this goal requires special consideration for patients with disability who need accommodations to access even basic services, such as physical examinations and weight measurement or to communicate effectively with physicians.2 Today, approximately 61 million Americans have a disability.3 Despite broad civil rights protections, which encompass health care, many people with disability experience health care disparities, as documented in federal reports, including Healthy People,4–7 and numerous studies.8–11 Research suggests that failures to receive accommodations contribute to inequitable care for people with disability.

Three major federal statutes mandate civil rights for people with disability: the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 Section 504, which applies to federal programs and settings; the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, which covers public and private services, including health care; and the ADA Amendments Act (ADAAA) of 2008, which aimed to clarify Congress’s intent in the ADA to define disability broadly for civil rights protections. Disability civil right protections differ importantly from civil rights mandates for other groups, such as racial or ethnic minorities.12 Disability civil rights laws both prohibit discrimination13 and require entities to “take proactive steps to offer equal opportunity to persons with disabilities.”14 Clinical practices fall under either ADA Title II (public) or III (private, but serving the public) and must provide “reasonable accommodations” to people with disability. Legal requirements differ somewhat between Title II and III settings. Nonetheless, all clinical practices must provide equal access to people with disability, accommodate their disability-related needs, and cannot refuse patients because of disability.15–17 ADA regulations stipulate that decisions about accommodations require collaboration, involving physicians’ judgments about what is clinically appropriate while emphasizing patients’ preferences.18,19 Patients cannot be required to provide their own accommodations, and health care practices, not patients,15,20 must pay accommodation costs.

The U.S. Department of Justice and the Office for Civil Rights, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services are responsible for enforcing the ADA in health care settings. Private individuals and groups may also file private ADA lawsuits. Public and private ADA enforcement actions and settlement agreements have challenged wide-ranging barriers experienced by individuals with disability in health care settings, including lack of reasonable accommodations to access care.21

Although all physicians providing direct patient care can expect to see patients with disability, little is known about the extent to which physicians nationwide understand their legal obligations under the ADA or the process for making accommodation decisions. To explore this issue, we conducted 20 open-ended, individual telephone interviews with outpatient physicians in Massachusetts, asking about their training, experiences with and perceptions of caring for people with disability, including their knowledge of ADA provisions. As described previously, the interviewees reported little training or understanding of the ADA, especially relating to reasonable accommodations.12

To examine these issues more broadly, we conducted the first national study, of which we are aware, of U.S. physicians practicing in outpatient settings and their experiences with and perceptions of caring for patients with disability. A previous publication described the study’s findings with respect to physicians’ attitudes toward caring for people with disability and their perceptions of quality of life with disability.22 Here, our major research question was the extent to which physicians across the U.S. correctly understand their various obligations to patients under the ADA, particularly concerning reasonable accommodations to ensure equitable care to patients with disability. We also explored physicians’ perceived risk of ADA lawsuits, as well as associations between physician characteristics, ADA knowledge, and perceived lawsuit risk.

Methods

The Massachusetts General Hospital/Partners Healthcare and University of Massachusetts-Boston Institutional Review Boards approved this study.

Survey Development and Testing

As described in detail elsewhere,22,23 we developed a new survey applicable for physicians practicing in 7 specialties: family medicine, general internal medicine, rheumatology, neurology, ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, and obstetrics-gynecology (OB/GYN). We selected the first 6 specialties because they see large numbers of outpatients with disability; we included OB/GYN because many women visit gynecologists for primary care and because prior research found frequent disability barriers in OB/GYN practices.11,24 As noted above, to inform survey development, we conducted 20 in-depth, open-ended, telephone individual interviews with outpatient physicians across the 7 specialties practicing in Massachusetts.12,25–27 We also performed 3 virtual focus groups with 22 physicians across 17 states practicing in the 7 specialties.28,29 We pretested the draft survey using 8 cognitive interviews and pilot tested the revised survey with 50 participants. The final survey has 75 questions within 8 modules, including one on the ADA (Appendix Exhibit 9).30

Sampling

Using commercially available data from IQVIA, we identified all board-certified U.S. physicians in the 7 specialties (n = 277,675). We then excluded: trainees (residents or fellows); locum tenens physicians; hospitalists (given our focus on outpatient practices); Veterans Affairs or military physicians (because outpatient practices for active duty military or veterans are often designed specifically to accommodate patients with disabling injuries, their experiences may not apply to civilian populations); physicians lacking complete addresses or telephone numbers; and physicians board-certified in both medicine and pediatrics (sampling frame = 172,734). We selected simple random samples of 350 each in family practice and general internal medicine and 140 in each other specialty, yielding 1,400 physicians (700 primary care and 700 specialists).

Survey Administration

We administered the survey starting in October 2019, with two follow-ups of nonrespondents (January and March 2020); we closed the survey in June 2020. The initial packet, sent by priority mail, contained an information sheet, a paper survey, postage-paid return envelope, and $50 cash incentive. A cover letter provided instructions and gave an individualized link to complete the survey online. The survey screened sampled physicians for eligibility (i.e., board certified in one of the 7 specialties, practicing actively in the U.S., at least 10 hours weekly providing direct outpatient care).

Among the 1,400 sampled physicians, we found that 175 (12.5 percent) were ineligible because of: screening question responses; being residents or fellows, retired, too ill, or deceased; having an inactive medical license or not practicing in the U.S.; or unreachable via mail, phone, or internet. Of the 1,225 eligible physicians, 714 completed the survey (84.2 percent on paper, 15.8 percent online). Employing American Association of Public Opinion Research response rate #3 for mailed surveys of specifically named participants, the weighted response rate was 61.0 percent.31 Response rates by specialty were: family medicine, 61.1 percent; general internal medicine, 63.2 percent; rheumatology, 57.7 percent; neurology, 58.0 percent; ophthalmology, 63.0 percent; orthopedic surgery, 58.6 percent; and OB/GYN, 61.6 percent.

Analytic Variables

Appendix Exhibit 130 defines all variables in the analyses with the exact language used in survey questions and response categories.

ADA-related Outcome Measures

Overall ADA Knowledge.

The survey asked participants how much they knew overall about their legal responsibilities as a physician under the ADA. We created a binary variable from the four response categories, combining “a lot” with “some” and combining “a little” with “nothing.”

Making accommodation decisions.

The survey asked participants who is responsible for determining reasonable accommodations for patients with disability being seen in their practice. Participants were instructed to check all that apply (see Appendix Exhibit 9)30 or specify other answers in the blank space provided. To be coded as correct, responses had to indicate that both physicians and patients are responsible. Recognizing that practices are organized differently, we coded responses as correct if participants checked patients/family along with either physician(s) caring for the patient or practice staff/managers/administrators, or if they checked all three of these responses. Any response that included insurers/payors was incorrect. We reviewed 23 open-ended responses, assigning each to the most appropriate option (correct versus incorrect).

Paying for accommodations.

The survey asked participants who is responsible for paying for reasonable accommodations provided to their patients with disability when cared for in their practice. The only correct answer was “owners of practice.” The other response categories (patients/family and insurers/payors) were grouped together in the analyses as incorrect.

Risk of ADA lawsuit.

The survey asked participants how much they felt their practices were at risk of an ADA lawsuit because of problems providing reasonable accommodations. We created a binary variable, with respondents reporting “no risk at all” in one group and those reporting “a lot of risk,” “some risk,” and “a little risk” into another group.

Other Analytic Variables About Care of Patients with Disability

Appendix Exhibits 4 and 530 show detailed responses within individual response categories for four additional analytic variables, as follows.

Lack of time.

We asked participants the extent to which lack of time is a barrier to caring for patients with disability. We dichotomized this variable as “not at all a barrier/small barrier” and “moderate/large barrier.”

Lack of formal education/training about disability.

We asked participants the extent to which lack of formal education/training is a barrier to caring for patients with disability. We likewise dichotomized the variable as “not at all a barrier/small barrier” and “moderate/large barrier.”

Confidence about caring for people with disability.

We asked participants how confident they are in their ability to provide the same quality of care to patients with disability as they provide to other patients. For analysis, we treated “very confident” as the positive outcome and all other responses (“somewhat confident,” “not very confident,” and “not at all confident”) as the negative outcome.

Welcoming patients with disability.

We asked participants about the extent to which they welcome patients with disability into their practices. We designated “strongly agree” as the positive outcome and all other responses as the negative outcome. The measures concerning confidence about caring for people with disability and welcoming them into practices were also included in analyses described in our prior publication.22

Analyses

We performed all analyses using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and SUDAAN 11.0.3 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). We weighted the data to account for differences in probabilities of selection and response rates within each specialty. For the bivariable analyses, we assessed the significance of differences in the group distributions of all variables with two-sided chi-square tests. We obtained adjusted percentages, associated 95% confidence intervals, and p-values based on Wald chi-square tests from multivariable logistic regressions that included the variables in Appendix Exhibit 7,30 including participants’ demographic and professional characteristics, that we hypothesized could be associated with the ADA outcome measures. We fit separate regression models for each of the four ADA outcomes. We viewed two-sided p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Limitations

Our survey has important limitations. Because this was the first national survey of physicians about caring for patients with disability and we wanted to maximize response rates by minimizing respondent burden, we addressed many topics, but none in depth. We did not ask questions that further explored participants’ perceptions of their legal responsibilities, or their ADA lawsuit risks. Budgetary constraints prevented us from including enough physicians within specialties to compare responses across specialties; we also could not include physicians in certain specialties, such as physiatry or geriatrics, that see many patients with disability. Given the distribution of U.S. physicians by race and ethnicity, we had too few Black or Hispanic participants to perform detailed analyses by race and ethnicity.

Results

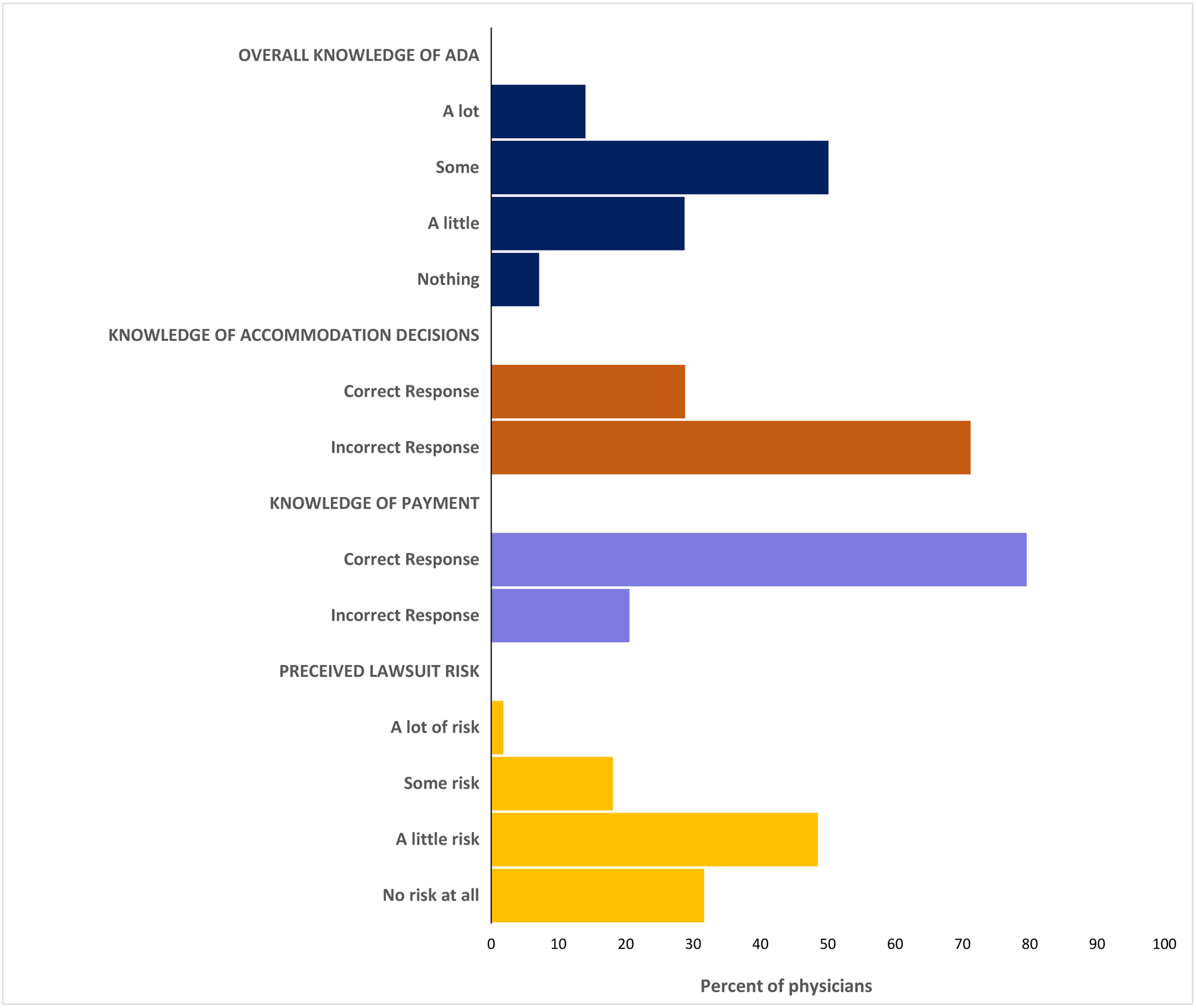

Appendix Exhibit 330 shows the distribution across all response categories for the four ADA outcome measures. In Exhibit 1, we highlight the correct versus incorrect responses regarding participants’ knowledge of their legal responsibilities, along with the measures of self-reported ADA knowledge and perceived lawsuit risk. Appendix Exhibit 630 shows participants’ personal, professional, and practice characteristics, their attitudes about caring for patients with disability, and their bivariable associations with the responses to the survey questions.

EXHIBIT 1.

Physicians’ knowledge and beliefs regarding the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), 2019–2020.

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from their survey, “Caring for Patients with Functional Limitations National Survey Funded by the NIH,” 2019–2020.

Notes: The data reflect survey questions that asked physicians to rate how much they know about legal obligations under the ADA; indicate who is responsible for determining reasonable accommodations for patients with disability; who is financially responsible for accommodations; and how much they perceived their practices to be at risk of ADA lawsuits. All survey questions are included in Appendix Exhibit 9.30

Survey participants were primarily male (62.0 percent), White (64.5 percent), in practice for 20 or more years (66.5 percent), and in community-based private practices (61.7 percent). Among participants, 47.7 percent viewed lack of time as a moderate or large barrier to caring for patients with disability, and 35.1 percent reported that lack of formal education or training was a moderate or large barrier to caring for patients with disability. As described previously,22 only 40.7 percent of participants felt very confident about providing equal quality care to patients with disability, and just 56.5 percent strongly welcomed them into their practices.

Except for gender, each participant characteristic or attitude had statistically significant bivariable associations with at least one of the four ADA outcomes. Appendix Exhibit 730 shows complete multivariable findings across the four ADA outcome measures. To highlight the most important associations, Exhibit 2 focuses on the independent variables that had a statistically significant relationship with at least one of the four ADA outcome measures; we define these variables as “selected characteristics.”

Exhibit 2.

Relationship between physician characteristics, ADA knowledge, and perceived lawsuit risk, 2019–2020

| Selected characteristics | ADA knowledge and ADA lawsuit risk | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported Knowledge of ADA responsibilities as little or nothing | Gave incorrect answer: who determines accommodations | Gave incorrect answer: who pays for accommodations | Perceived to be at risk of ADA Lawsuit in practice | |

| adjusted percent | ||||

| Personal characteristics | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 33.9 | 69.2 | 13.6 | 72.1 |

| Asian | 39.2 | 80.8 | 23.2 | 71.7 |

| Hispanic/African American/Other | 42.0 | 79.0 | 27.4 | 67.7 |

| p-value | 0.35 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| Self or family member has significant limitation(s) | ||||

| Yes | 31.3 | 76.5 | 16.4 | 76.6 |

| No | 38.9 | 70.3 | 18.1 | 68.1 |

| p-value | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 0.04 |

| Professional or practice characteristics | ||||

| Owner or co-owner of practice | ||||

| Yes | 28.7 | 68.1 | 22.5 | 71.9 |

| No | 41.5 | 75.9 | 15.0 | 70.9 |

| p-value | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.84 |

| Number of physicians in practice | ||||

| Very small (1–3 physicians) | 40.3 | 73.6 | 15.9 | 81.5 |

| Small (4–11 physicians) | 31.6 | 71.9 | 18.0 | 66.1 |

| Large (12+ physicians) | 40.9 | 73.3 | 18.6 | 66.4 |

| p-value | 0.15 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.003 |

| Percent of patients with Medicaid or uninsured/self-pay | ||||

| Non-safety net provider (< 35 percent) | 36.3 | 72.1 | 14.5 | 71.6 |

| Safety net provider (≥ 35 percent) | 35.8 | 74.3 | 23.5 | 70.8 |

| p-value | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.86 |

| Other questions about caring for patients with disability | ||||

| Lack of formal education/training | ||||

| Not a barrier at all/small barrier | 31.9 | 73.0 | 18.6 | 67.1 |

| Moderate/large barrier | 43.3 | 72.4 | 15.8 | 80.6 |

| p-value | 0.02 | 0.90 | 0.47 | 0.004 |

| Confidence in ability to provide same quality care to patients with disability | ||||

| Not very confident | 40.5 | 74.8 | 19.2 | 82.2 |

| Very confident | 28.6 | 69.4 | 14.7 | 55.8 |

| p-value | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.27 | < 0.0001 |

| Welcome patients with disability into practice | ||||

| Not strongly agree | 42.8 | 75.9 | 19.9 | 74.1 |

| Strongly agree | 30.4 | 70.2 | 15.4 | 69.4 |

| p-value | 0.009 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.27 |

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from their survey, “Caring for Patients with Functional Limitations National Survey Funded by the NIH,” 2019–2020.

Notes: Survey questions are included in Appendix Exhibit 9.30

Results were obtained from multivariable logistic regressions assessing the relationship of the four outcomes shown in the columns and including all characteristics shown in Appendix Exhibit 7. “Selected characteristics” are defined as those that had at least one significant finding among the four outcomes.

P-values are based on Wald Chi-square tests from the regressions. ADA = Americans with Disabilities Act.

Overall Knowledge of Responsibilities Under the ADA

Across all participants, 35.8 percent reported knowing little or nothing about their responsibilities under the ADA. Participants more likely to report little or no knowledge of their ADA responsibilities were physicians who: did not own/co-own their practice (41.5 percent versus 28.7 percent (p = 0.03)); reported lack of formal education/training as a moderate/large barrier (43.3 percent versus 31.9 percent (p = 0.02)); were not very confident of providing same quality care to patients with disability (40.5 percent versus 28.6 percent (p =0.02)); or did not strongly welcome persons with disability into their practice (42.8 percent versus 30.4 percent (p = 0.009)).

Knowledge of Responsibility for Making Accommodation Decisions

Across all participants, 71.2 percent provided incorrect answers about who makes decisions about reasonable accommodations. Our multivariable analyses did not find any participant characteristics that were significantly associated with this outcome measure (Appendix Exhibit 730).

Knowledge of Who Pays for Accommodations

Across all participants, 20.5 percent provided incorrect answers about who pays for reasonable accommodations for patients with disability. Participants more likely to report incorrect answers about who pays for accommodations were physicians who: were Hispanic, African American or other race (27.4 percent) or Asian (23.2 percent) rather than White (13.6 percent (p = 0.03)); or were a safety-net provider (23.5 percent versus 14.5 percent (p = 0.03)).

Perceived Risk of ADA Lawsuits

Across all participants, 68.4 percent believed that they were at risk of an ADA lawsuit because of accommodation problems. Participants more likely to report some ADA lawsuit risk were physicians who: themselves or a family member had a significant functional limitation (76.6 percent versus 68.1 percent (p = 0.04)); practiced in very small practices, (81.5 percent versus 66.1 percent for small and 66.4 percent for large practices (p = 0.003)); reported lack of education/training as a moderate/large barrier (80.6 percent versus 67.1 percent (p = 0.004)); or were not very confident in their ability to provide the same quality of care to patients with disability (82.2 percent versus 55.8 percent (p < 0.0001)).

Discussion

Providing reasonable accommodations is critical to ensure equitable care for patients with disability. However, more than one-third of survey participants reported knowing little or nothing about their responsibilities under the ADA. Participants who felt that lack of formal education/training was a moderate or large barrier to caring for patients with disability were more likely to report little or no knowledge of their responsibilities under the law. More than 70 percent of survey participants gave incorrect answers when asked who is responsible for making accommodation decisions. More than two-thirds of participants felt that they were at risk of an ADA lawsuit. Physicians who reported lack of formal education or training as a moderate or large barrier to caring for patients with disability and who were not very confident about being able to provide the same quality care to patients with disability were much more likely to feel at risk of ADA lawsuits.

Our results raise several concerns. First, these findings underscore the need for more training about disability and disability civil rights, including physicians’ responsibilities under the ADA, in medical school, post-graduate training, and continuing medical education. As more medical schools add disability topics to their curricula,32–36 rigorous studies should investigate the most productive educational approaches for teaching medical students about their legal obligations to patients with disability. Survey results reported previously22 – that more than four-fifths of physicians think people with significant disability have worse quality of life than others – raise questions about a potential “hidden curriculum” in medical training. With this hidden curriculum, trainees may be socialized through unspoken and implicit biases of their instructors. These biases could influence trainees’ uptake and retention of information about the ADA. Practice experiences after training might also powerfully affect ADA knowledge. Physicians who did not own their practices were more likely than owners to report little or no overall knowledge of their responsibilities under the ADA. The daily demands of running a practice may bolster physicians’ knowledge of regulatory requirements, such as accommodations and other responsibilities under the ADA.

Second, the lack of knowledge about who makes accommodation decisions raises troubling questions about health care quality and equity. Studies of patients with disability suggest that, without accommodations such as accessible medical diagnostic equipment, they may receive substandard care.37–40 Patients who use wheelchairs report being routinely examined in their wheelchairs rather than transferred onto exam tables.40,41 Even with accessible exam tables, some physicians do not transfer patients who use wheelchairs, leaving patients dissatisfied with their care.39 For patients with vision, hearing, or speech disability, the ADA requires that providers ensure “effective communication,” by prioritizing patients’ preferences for what would constitute reasonable communication accommodations (e.g., verbally describing exam room and medical equipment for people who are blind, providing on-site sign language interpreter for people who are deaf).19,42,43 However, patients who are deaf or hard of hearing, for example, report that their preferences for effective communication accommodations are often not followed.44,45

Appendix Exhibit 830 provides examples of reasonable accommodations by disability type. When making decisions about reasonable accommodations, ADA Title II entities (practices supported by state or local governments, such as federally qualified health centers or publicly-funded hospital clinics) are legally required to give patients’ preferences primary consideration, while Title III entities (private practices serving the public) are encouraged to consult patients and emphasize their needs.42 Thus, in both contexts, specifying reasonable accommodations should involve collaborative discussions between physicians and patients. Although the ADA provides a clear framework for accommodating the needs of patients with disability, the law requires enforcement to be effective. Despite public and private enforcement efforts, federal agencies, academic researchers, and others have documented failures to meet ADA requirements in health care settings.21,46 Policy changes should strengthen current laws. For example, existing federally-approved standards from the U.S. Access Board for accessible medical diagnostic equipment should become enforceable ADA requirements, to clarify the obligations of health care providers.21

Third, physicians reporting not being very confident about providing the same quality care to people with disability were more likely to report little or no knowledge of their responsibilities under the ADA and believe they were at risk of an ADA lawsuit. More research is needed to identify strategies for improving practicing physicians’ confidence in providing equitable care to people with disability. A recent “Call to Action” urged preparation of a disability competent health care workforce.47 Implementing disability competence into educational curricula is an important step,48 but a long lead time elapses before trainees become practitioners. Continuing medical education (CME) offers opportunities for training the current physician workforce about caring for patients with disability. Available studies suggest that CME can positively affect clinical practices and patient outcomes, albeit often modestly.49 Given the pressing need, using CME to educate physicians about accommodating patients with disability seems worthwhile, with appropriate evaluation of CME’s effects.

More than 30 years following enactment of the ADA, patients with disability continue to experience health care disparities. Failures to provide reasonable accommodations to these patients contribute to disparities. Might the common exclusion of people with disability from important professional pronouncements about ensuring equitable care contribute to inadequate knowledge about making reasonable accommodations among practicing physicians? For example, social justice is among the three core principles in the 2002 Charter on Medical Professionalism: “Physicians should work actively to eliminate discrimination in health care, whether based on race, gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, religion, or any other social category.”1 In 2020, the American College of Physicians’ Call to Action, Envisioning a Better Health Care System for All, urges overcoming “the many systematic barriers to care that Americans face, including discrimination because of personal characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, religion, language, sex and sexual orientation, gender and gender identity, and country of origin.”50 Neither the 2002 Charter nor the 2020 Call to Action mention people with disability in their exhortations about equity and social justice.

Conclusion

Because of demographic and other factors, the population of Americans with disability will grow substantially in coming decades. Most practicing physicians can therefore expect to see increasing numbers of patients with disability in their practices. Including physicians in initiatives to eliminate systemic discrimination and barriers to care, such as improving physical accessibility throughout care sites,23 is therefore critical. However, making care accessible starts at decisions for individual patients. To ensure equitable health care, patients with disability must receive the reasonable accommodations during their clinical encounters that are their civil right under the ADA and a moral imperative under codes of conduct for medical professionals. Our survey findings suggest there is considerable work to do – in educating physicians and making health care delivery systems more accessible and accommodating – to achieve equitable care and social justice for patients with disability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Joy Hamel, PhD, OTR/L, Kristi L. Kirschner, MD, and Mary Lou Breslin for their contributions to designing the focus group moderator’s guide and the survey questions. We also thank Karen Donelan, ScD, MEd, for her insights and survey expertise.

Funding source:

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, R01HD091211-02

References

- 1.ABIM Foundation, American Board of Internal Medicine, ACP-ASIM Foundation, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagu T, Iezzoni LI, Lindenauer PK. The axes of access — improving care for patients with disabilities. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1847–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, Griffin-Blake S. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(32):882–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010, Vols. 1–2: With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmona RH, Cabe J. Improving the health and wellness of persons with disabilities: a call to action. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(11):1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2010 National Healthcare Disparities Report. AHRQ Publication No. 10-0005 [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. [cited 2020 Dec 17]. Available from: https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr10/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healthy People 2020. Disability and Health. Topics & objectives [Internet]. Weshington, D.C.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [cited 2020 April 9]. Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/disability-and-health [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iezzoni LI. Eliminating health and health care disparities among the growing population of people with disabilities. Health Aff. 2011;30(10):1947–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meade MA, Mahmoudi E, Lee S-Y. The intersection of disability and healthcare disparities: a conceptual framework. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(7):632–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa-De-Araujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:S198–S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagu T, Hannon NS, Rothberg MB, Wells AS, Green KL, Windom MO, et al. Access to subspecialty care for patients with mobility impairment: a survey. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(6):441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agaronnik ND, Pendo E, Campbell EG, Ressalam J, Iezzoni LI. Knowledge of practicing physicians about their legal obligations when caring for patients with disability. Health Aff. 2019;38(4):545–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section. A guide to disability rights laws [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section; February 2020. [cited 2020 Dec 17]. Available at: https://www.ada.gov/cguide.htm [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young JM. Equality of Opportunity: The Making of the Americans with Disabilities Act [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Council on Disability; 2010:206. [cited 2020 Dec 17]. Available at: https://ncd.gov/publications/2010/equality_of_Opportunity_The_Making_of_the_Americans_with_Disabilities_Act [Google Scholar]

- 15.General Prohibitions against Discrimination, 28 C.F.R. § 35.130 (2016).

- 16.Activities, 28 C.F.R. § 36.202 (1992).

- 17.Prohibition of Discrimination by Public Accommodations, 42 U.S. Code § 12182 (1990).

- 18.General, 28 C.F.R. §35.160(b)(2) (2011).

- 19.Auxiliary Aids and Services, 28 C.F.R. §36.303(2011).

- 20.Eligibility Criteria, 28 C.F.R. § 36.301 (1991).

- 21.National Council on Disability. The current state of health care for people with disabilities [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Council on Disability; 2019. [Cited 2021 Feb 9]. Available at: https://www.ncd.gov/publications/2009/Sept302009 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Ressalam J, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Agaronnik ND, Donelan K, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of people with disability and their health care. Health Aff. 2021;40(2):297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Ressalam J, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Donelan K, Agaronnik N, et al. Use of accessible weight scales and examination tables/chairs for patients with significant mobility limitations by physicians nationwide. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Safety. 2021;47:615–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitra M, Akobirshoev I, Moring NS, Long-Bellil L, Smeltzer SC, Smith LD, et al. Access to and satisfaction with prenatal care among pregnant women with physical disabilities: Findings from a national survey. J Women’s Health. 2017;26(12):1356–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agaronnik N, Campbell EG, Ressalam J, Iezzoni LI. Accessibility of medical diagnostic equipment for patients with disability: Observations from physicians. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(11):2032–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agaronnik N, Campbell EG, Ressalam J, Iezzoni LI. Communicating with patients with disability: perspectives of practicing physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1139–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agaronnik N, Campbell EG, Ressalam J, Iezzoni LI. Exploring issues relating to disability cultural competence among practicing physicians. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(3):403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agaronnik N, Pendo E, Lagu T, DeJong C, Perez-Caraballo A, Iezzoni LI. Ensuring the reproductive rights of women with intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2020;45(4):365–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agaronnik ND, Lagu T, DeJong C, Perez-Caraballo A, Reimold K, Ressalam J, et al. Accommodating patients with obesity and mobility difficulties: Observations from physicians. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(1):100951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.To access the Appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 31.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions report: final dispositions of case codes and outcomes for surveys [Internet].. Washington, DC: American Association for Public Opinion Research. 2016. [cited 2021 Oct 21]. Available from: https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirschner KL, Curry RH. Educating health care professionals to care for patients with disabilities. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1334–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Symons AB, McGuigan D, Akl EA. A curriculum to teach medical students to care for people with disabilities: Development and initial implementation. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lynch J, Last J, Dodd P, Stancila D, Linehan C. ‘Understanding Disability’: Evaluating a contact-based approach to enhancing attitudes and disability literacy of medical students. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(1):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minihan PM, Robey KL, Long-Bellil LM, Graham CL, Hahn JE, Woodard L, et al. Desired educational outcomes of disability-related training for the generalist physician: Knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Acad Med. 2011;86(9):1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Long-Bellil LM, Robey KL, Graham CL, Minihan PM, Smeltzer SC, Kahn P. Teaching medical students about disability: The use of standardized patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(9):1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Story MF, Schwier E, Kailes JI. Perspectives of patients with disabilities on the accessibility of medical equipment: Examination tables, imaging equipment, medical chairs, and weight scales. Disabil Health J. 2009;2(4):169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrison EH, George V, Mosqueda L. Primary care for adults with physical disabilities: Perceptions from consumer and provider focus groups. Fam Med. 2008;40(9):645–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris MA, Maragh-Bass AC, Griffin JM, Finney Rutten LJ, Lagu T, Phelan S. Use of accessible examination tables in the primary care setting: a survey of physical evaluations and patient attitudes. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1342–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iezzoni LI, Kilbridge K, Park ER. Physical access barriers to care for diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women with mobility impairments. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(6):711–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Vries McClintock HF, Barg FK, Katz SP, Stineman MG, Krueger A, Colletti PM, et al. Health care experiences and perceptions among people with and without disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(1):74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Department of Justice. Civil Rights Division, Disability Rights Section. ADA Requirements: Effective Communication [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2014. January [Cited 2021 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.ada.gov/effective-comm.htm [Google Scholar]

- 43.General, 28 CFR §35.160. (2010).

- 44.Iezzoni LI, O’Day BL, Killeen M, Harker H. Communicating about health care: observations from persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(5):356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinberg AG, Barnett S, Meador HE, Wiggins EA, Zazove P. Health care system accessibility: Experiences and perceptions of deaf people. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(3):260–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lagu T, Griffin C, Lindenauer PK. Ensuring access to health care for patients with disabilities. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):157–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowen CN, Havercamp SM, Karpiak Bowen S, Nye G. A call to action: Preparing a disability-competent health care workforce. Disabil Health J. 2020;13(4). 100941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Havercamp SM, Barnhart WR, Robinson AC, Whalen Smith CN. What should we teach about disability? National consensus on disability competencies for health care education. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(2): 100989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forsetlund L, Bjørndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O’Brien MA, Wolf F, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(2):CD003030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doherty R, Cooney TG, Mire RD, Engel LS, Goldman JM. Envisioning a better U.S. health care system for all: a call to action by the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2 Supplement):S3–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.