Abstract

Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) fingerprinting of clinical isolates of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars D, E, and F showed a low percentage of genetic heterogeneity, but clear differences were found. Isolates from index patients and partners had identical AFLP patterns and AFLP markers. Characterization of these AFLP markers could give more insight into the differences in virulence and clinical course of C. trachomatis infections.

It is still unknown why infections with particular Chlamydia trachomatis serovars run either a symptomatic or an asymptomatic clinical course. Several studies have shown relationships between specific serovars and clinical disease, but the results are still contradictory (6, 11, 20, 29). It is not unlikely that variation at the genomic level could give more insight into the differences in virulence, tissue tropism, disease pathogenesis, and epidemiology. Furthermore, it could lead to the identification of strains within one serovar with different pathogenic features that could explain the differences in disease manifestations found in the literature for isolates of the same serovar. The serotyping (18, 21) and genotyping (7, 14, 18, 19) techniques for C. trachomatis are based on variations in one gene or protein: the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) or its gene, omp1. However, Chlamydia species and C. trachomatis isolates have also been differentiated at the genomic level by genomic restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (23, 24), random amplification of polymorphic DNA (26), arbitrary primer PCR (13), genomic hybridization (5), and rRNA spacer analysis (15). Recently, a new fingerprinting technique has been developed: amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis (30). This PCR-based fingerprinting technique has shown to be a reproducible and powerful tool for taxonomic, diagnostic, and epidemiological applications (9, 10, 25, 30). The specific advantages of AFLP analysis over the conventionally used techniques are its use of small amounts of DNA (10 to 50 ng) and its reproducibility. This study aimed to optimize AFLP for investigation of genomic variation in C. trachomatis. Variation between and within isolates of the most prevalent urogenital C. trachomatis serovars, serovars D, E, and F, of the trachoma biovar was analyzed.

C. trachomatis isolates obtained from 29 heterosexual patients and their C. trachomatis-infected partners were included in this study (13). C. trachomatis serovars were determined by a PCR-based RFLP analysis of the omp1 gene and by serotyping (14, 18): 5 pairs were infected with serovar D, 13 pairs were infected with serovar E, and 11 pairs were infected with serovar F (the pairs are numbered from 1 to n for each serovar, the index patient is indicated by the letter A, and the partner is indicated by the letter B).

Cell culture was performed by routine procedures (18, 21). C. trachomatis elementary body (EB) DNA was isolated by treating a sonicated cell culture suspension with DNase I, proteinase K, and RNase A, followed by EB DNA isolation with the High Pure PCR Template Preparation kit (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Each specimen was subjected to amplification by a 206-bp β-globin PCR to check for the presence of human DNA (12). C. trachomatis plasmid-specific primers were used to detect C. trachomatis DNA (17). Mycoplasma DNA was detected by PCR as described previously (22) to ensure that there was no contaminating mycoplasmal DNA. For DNA fingerprinting by AFLP analysis (10, 16, 30), C. trachomatis DNA was digested with EcoRI (New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, Mass.) and MseI (New England Biolabs Inc.). AFLP images were analyzed with GelCompar, version 4.0, software. The similarity was expressed by the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient (r), and groupings were obtained by the unweighted pair-group matrix analysis (UPGMA) clustering algorithm as described previously (16).

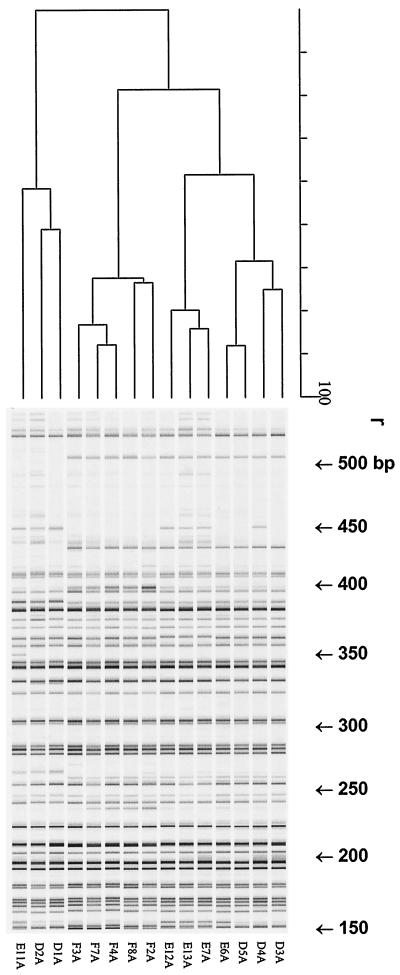

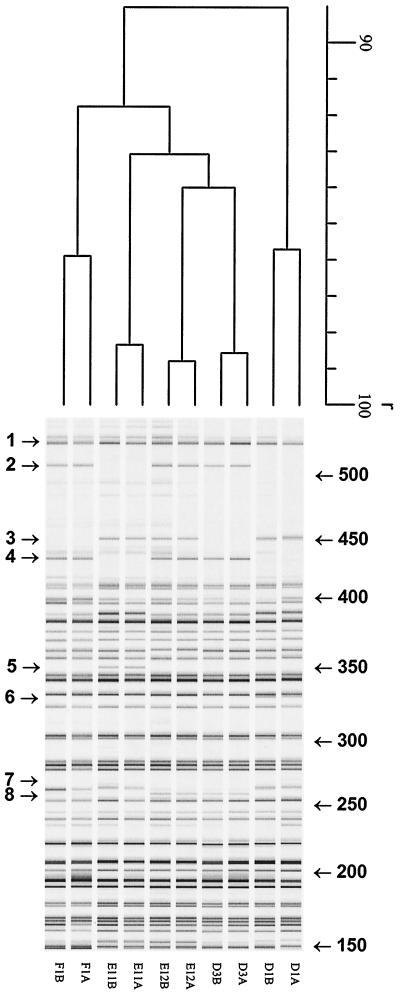

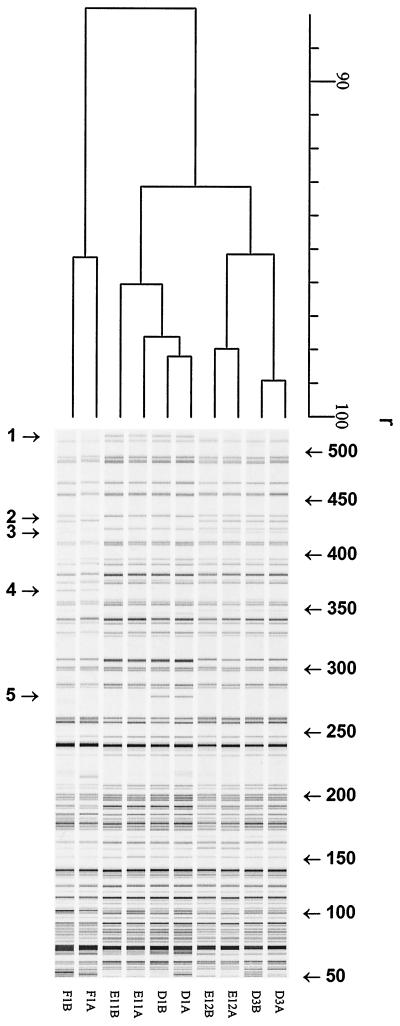

The isolated C. trachomatis DNA was free of human and mycoplasma DNA, as assessed by PCR, ensuring C. trachomatis-specific fingerprinting patterns in the AFLP analysis. Different primer combinations with 0 or 1 selection base were tested (Eco0 and Mse-C, Eco-A and Mse-0, Eco0 and Mse-0) by using the five serovar D pairs. The most discriminatory primer combination for AFLP analysis appeared to be the pair Eco0–Mse-C. Figure 1 shows representative AFLP patterns for 15 strains of serovars D, E, and F (five strains of each serovar). Clustering was found at r equal to 91.0% ± 2.3% for serovars D, E, and F. Both unique AFLP markers and markers which were absent from specific strains were found. In addition, different AFLP markers were observed between 425 and 525 bp. However, while three different marker patterns were found for serovars E and D (Table 1, patterns A, B and C), only pattern B was found for serovar F. Of the most aberrant strains (from index patients), the corresponding strains from the partners have also been analyzed by AFLP analysis, as shown in Fig. 2 (eight different AFLP markers are indicated; r = 89.0% ± 3.6%). Interestingly, these specific AFLP markers are identical for both index patients and their partners. To confirm the existence of different strains within C. trachomatis serovars D, E, and F identifiable by the presence or absence of AFLP markers, five strains were further analyzed by AFLP analysis with Eco-A–Mse0. As shown in Fig. 3 (F1, D1, D3, E11, and E12, strains from both the index patient and the partner; r = 87.8% ± 2.1%), this independent AFLP analysis confirmed the existence of different strains of the same serovar, since in this AFLP analysis identical unique AFLP markers were also found for strains from both index patients and their partners.

FIG. 1.

Digitized AFLP patterns and dendrograms for the three most prevalent urogenital C. trachomatis serovars, serovars D, E, and F. The dendrograms were constructed by the UPGMA clustering method. AFLP analysis was performed with primers MseC and Eco-0. The scale represents the product-moment correlation coefficient (r; in percent).

TABLE 1.

Patterns of C. trachomatis AFLP markers between 425 and 525 bp

| Pattern | AFLP marker no.a | Strain example |

|---|---|---|

| A | 1, 2, 3, and 4 | D4, E12 |

| B | 1, 2, and 4 | D3, E6, F3 |

| C | 1 and 3 | D1, E11 |

AFLP markers 1 to 4 are indicated in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Digitized AFLP patterns and dendrograms for C. trachomatis serovar D, E, and F isolates: pairs from index patients (A) and the corresponding partners (B). The dendrograms were constructed by the UPGMA clustering method. AFLP analysis was performed with primers Mse-C and Eco-0. The scale represents the product-moment correlation coefficient (r; in percent). Arrows indicate AFLP markers.

FIG. 3.

Digitized AFLP patterns and dendrograms for pairs of C. trachomatis serovar D, E, and F isolates. The dendrograms were constructed by the UPGMA clustering method. AFLP analysis was performed with primers Mse-0 and Eco-A. The scale represents the product-moment correlation coefficient (r; in percent). Arrows indicate AFLP markers.

This study showed that although genomic heterogeneity was small (Fig. 1 and 2), within C. trachomatis serovars D, E, and F unique AFLP markers were observed. These AFLP markers were confirmed by the identical AFLP patterns found for isolates from the corresponding partners. When a different primer combination was applied, the existence of strain variants was confirmed by showing unique AFLP markers, as shown in Fig. 3, emphasizing both the reliability and usefulness of this fingerprinting approach. However, since the differences are small but reproducible, it is advisable that strains be analyzed in the same PCR run and the same polyacrylamide gel. Phylogenetic analysis of the C. trachomatis MOMP and the omp1 gene showed no evolutionary relationships among serovars that corresponded to biological or pathological phenotypes (tissue tropism, disease manifestation, and epidemiological success) (28). Since AFLP analysis showed genomic variation between and within C. trachomatis serovars and AFLP analysis of C. pneumoniae (2) and C. psittaci (1) yielded clusters that correlated with clinical syndromes, it could be a valuable tool for answering the intriguing question of whether specific C. trachomatis strains that cause symptomatic and asymptomatic infections exist within a particular serovar. For this, the use of different enzymes and primer pairs could potentially enlarge the genomic variations found. Characterization of the AFLP markers found at the gene level by cloning and sequencing (3, 4) will be greatly facilitated by the recently published C. trachomatis genome sequence (27). Other techniques have been used to differentiate C. trachomatis strains at the genome level (8, 23, 24) and also found intraserovar heterogeneities. However, one of the important advantages of AFLP analysis over non-PCR-based genomic analysis is that instead of the 1 μg of C. trachomatis DNA needed for RFLP analysis, only 10 to 50 ng of C. trachomatis DNA is needed for AFLP analysis, significantly reducing the labor needed to propagate chlamydial strains (instead of the usual four to six six-well plates, only four shell vials were needed).

In conclusion, although the genetic heterogeneity by AFLP fingerprinting of C. trachomatis clinical urogenital isolates of serovars D, E, and F was low, clear AFLP markers were found. By this approach the unique AFLP markers found could be characterized and the observed differences in pathogenicity of C. trachomatis might be related to particular strains and/or specific genes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boumedine K S, Rodolakis A. AFLP allows the identification of genomic markers of ruminant Chlamydia psittaci strains useful for typing and epidemiological studies. Res Microbiol. 1998;149:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)80020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter M W, Harrison T G, Shafi M S, Gearge R C. Typing strains of Chlamydia pneumoniae by amplified fragment length polymorphism typing. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998;4:663–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1998.tb00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalhoud B A, Thibault S, Laucou V, Rameau C, Hofte H, Cousin R. Silver staining and recovery of AFLP amplification products on large denaturing polyacrylamide gels. BioTechniques. 1997;22:216–218. doi: 10.2144/97222bm03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho Y G, Blair M W, Panaud O, McCouch S R. Cloning and mapping of variety-specific rice genomic DNA sequences: amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) from silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Genome. 1996;39:373–378. doi: 10.1139/g96-048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox R L, Kuo C C, Grayston J T, Campbell L A. Deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness of Chlamydia sp. strain TWAR to Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia psittaci. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:265–268. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean D, Oudens E, Bolan G, Padian N, Schachter J. Major outer membrane protein variants of Chlamydia trachomatis are associated with severe upper genital tract infections and histopathology in San Francisco. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1013–1022. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frost E H, Deslandes S, Veilleux S, Bourgaux-Ramoisy D. Typing Chlamydia trachomatis by detection of restriction fragment length polymorphism in the gene encoding the major outer membrane protein. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1103–1107. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.5.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrmann B, Winqvist O, Mattsson J G, Kirsebom L A. Differentiation of Chlamydia spp. by sequence determination and restriction endonuclease cleavage of the RNase P RNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1897–1902. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.8.1897-1902.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen P, Coopman R, Huys G, Swings J, Bleeker M, Vos P, Zabeau M, Kersters K. Evaluation of the DNA fingerprinting method AFLP as a new tool in bacterial taxonomy. Microbiology. 1996;42:1881–1893. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koeleman J G M, Stoof J, Biesmans D J, Savelkoul P H M, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C M J E. Comparison of amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis, random amplified polymorphic DNA, and amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting for identification of Acinetobacter genomic species and typing of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2522–2529. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2522-2529.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lampe M F, Wong K G, Stamm W E. Sequence conservation in the major membrane protein gene among Chlamydia trachomatis strains isolated from the upper and lower genital tract. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:589–592. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan J, van den Brule A J C, Hemrika D J, Risse E K, Walboomers J M M, Schipper M E I, Meijer C J L M. Chlamydia trachomatis and ectopic pregnancy: retrospective analysis of salpingectomy specimens, endometrial biopsies and cervical smears. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:815–819. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.9.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lan J, van den Hoek A, Ossewaarde J M, Walboomers J M M, van den Brule A J C. Genotyping of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars derived from heterosexual partners and a detailed genomic analysis of serovar F. Genitourin Med. 1995;71:299–303. doi: 10.1136/sti.71.5.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lan J, Ossewaarde J M, Walboomers J M M, Meijer C J L M, van den Brule A J. Improved PCR sensitivity for direct genotyping of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars by using a nested PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:528–530. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.528-530.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meijer A, Kwakkel G J, de Vries A, Schouls L M, Ossewaarde J M. Species identification of Chlamydia isolates by analyzing restriction fragment length polymorphism of the 16S-23S rRNA spacer regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1179–1183. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1179-1183.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meijer A, Morré S A, van den Brule A J C, Savelkoul P H M, Ossewaarde J M. Genomic relatedness of Chlamydia isolates determined by amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4469–4475. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4469-4475.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morré S A, Sillekens P, Jacobs M V, van Aarle P, de Blok S, van Gemen B, Walboomers J M M, Meijer C J L M, van den Brule RNA amplification by nucleic acid sequence-based amplification with an internal standard enables reliable detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in cervical scrapings and urine samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3108–3114. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3108-3114.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morré S A, Ossewaarde J M, Lan J, van Doornum G J J, Walboomers J M M, MacLaren D M, Meijer C J L M, van den Brule A J C. Serotyping and genotyping of genital Chlamydia trachomatis isolates reveal variants of serovars Ba, G, and J as confirmed by omp1 nucleotide sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:345–351. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.345-351.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morré S A, Moes R, Van Valkengoed I G M, Boeke A J P, van Eijk J T M, Meijer C J L M, Van den Brule A J C. Genotyping of Chlamydia trachomatis in urine specimens will facilitate large epidemiological studies. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3077–3078. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3077-3078.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morré S A, Rozendaal L, van Valkengoed I G M, Boeke A J P, van Voorst-Vader P C, Schirm J, de Blok S, van Doornum G J J, van den Hoek J A R, Meijer C J L M, van den Brule A J C. Urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis serovars in men and women having either a symptomatic or an asymptomatic infection: an association with clinical manifestations. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2292–2296. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2292-2296.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ossewaarde J M, Rieffe M, de Vries A, Derksen-Nawrocki R P, Hooft H J, van Doornum G J J, van Loon A M. Comparison of two panels of monoclonal antibodies for determination of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2968–2974. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2968-2974.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ossewaarde J M, de Vries A, Besteboer T, Angulo A F. Application of a Mycoplasma group-specific PCR for monitoring decontamination of Mycoplasma-infected Chlamydia sp. strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:328–331. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.328-331.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson E M, de la Maza L M. Restriction endonuclease analysis of DNA from Chlamydia trachomatis biovars. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:625–629. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.4.625-629.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez P, Allerdat-Servant A, de Bardeyrac B, Ramuz M, Bebear C. Genetic variability among Chlamydia trachomatis reference and clinical strains analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2921–2928. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2921-2928.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savelkoul P H M, Aarts H J M, de Haas J, Dijkshoorn L, Duim B, Otsen M, Rademaker J L M, Schouls L, Lenstra J A. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP): the state of an art. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3083–3091. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3083-3091.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scieux C, Grimont F, Regnault B, Bianchi A, Kowalski S, Grimont A N D. Molecular typing of Chlamydia trachomatis by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90197-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens R S, Kalman S, Lammal C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov R L, Zhau Q, Koonin E V, Davis R W. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science. 1998;282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stothard D R, Boguslawski G, Jones R B. Phylogenetic analysis of the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein and examination of potential pathogenic determinants. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3618–3625. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3618-3625.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van de Laar M J W, Lan J, van Duynhoven Y T H P, Fennema J S A, Ossewaarde J M, van den Brule A J C, van Doornum G J J, Coutinho R A, van den Hoek J A R. Differences in clinical manifestations of genital chlamydial infections related to serovars. Genitourin Med. 1996;72:261–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, Reijans M, van de Lee T, Hornes M, Frijters A, Pot J, Peleman J, Kuiper M, Zabeau M. AFLP™: a new concept for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]