Abstract

The design and understanding of rejection mechanisms for both positively and negatively charged nanofiltration (NF) membranes are needed for the development of highly selective separation of multivalent ions. In this study, positively charged nanofiltration membranes were created via an addition of commercially available polyallylamine hydrochloride (PAH) by conventional interfacial polymerization technique. Demonstration of real increase in surface zeta potential, along with other characterization methods, confirmed the addition of weak basic functional groups from PAH. Both positively and negatively charged NF membranes were tested for evaluating their potential as a technology for the recovery or separation of lanthanide cations (neodymium and lanthanum chloride as model salts) from aqueous sources. Particularly, the NF membranes with added PAH performed high and stable lanthanides retentions, with values around 99.3% in mixtures with high ionic strength (100 mM, equivalent to ~6,000 ppm), 99.3% rejection at 85% water recovery (and high Na+/La3+ selectivity, with 0% Na+ rejection starting at 65% recovery), and both constant lanthanum rejection and permeate flux at even pH 2.7. Donnan steric pore model with dielectric exclusion elucidated the transport mechanism of lanthanides and sodium, proving the potential of high selective separation at low permeate fluxes using positively charged NF membranes.

Keywords: Nanofiltration, Positively charged membrane, Lanthanides separation, DSPM-DE, Zeta potential

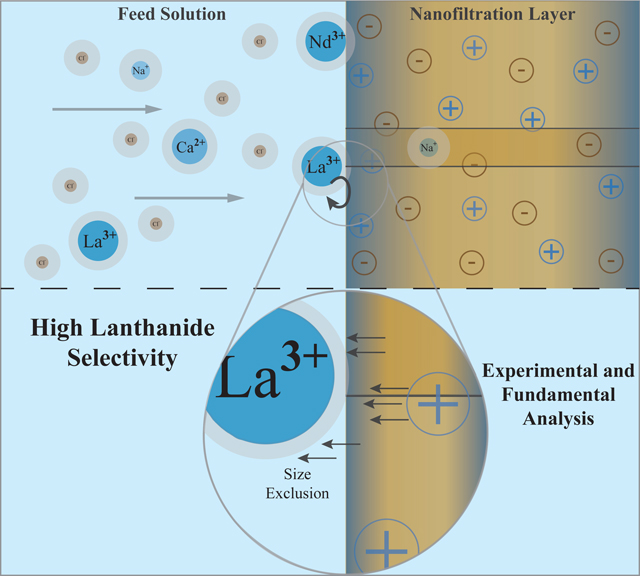

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Nanofiltration (NF) membranes have the ability to selectively separate ions by contribution of different partitioning terms, such as size, Donnan (electrical potential) and dielectric exclusions [1,2]. Tunability of these membranes is promising for rejection of desired compounds and ssimultaneous reduction of energy consumption (by decreasing the osmotic pressure relative to denser membranes). These membranes can be used for rejection of low molecular weight molecules (above ~300 Da) to monovalent and multivalent ions, with suitable applications [3] such as water softening, semi-demineralization and recovery of lactose from whey [4], some newer applications with solvent resistant membranes [5,6], among others [7,8]. A specific potential application for NF membranes is the recovery of lanthanides from aqueous solutions. Lanthanides cations are trivalent cations with considerably large size, characteristics that can enhance selectivity compared to other ions. Moreover, they are widely used in modern life [9] and can be found in magnets for computers and automobiles, or in batteries and fuel cells as metal alloys, or in catalysts, among other areas. High current market prices make them even more valuable, as for example, neodymium oxide and lanthanum oxide which are around 44,000 and 16,000 USD/mt, respectively. As a consequence of the high demand of these rare earth elements (REE), new sources have been investigated and coal reserves have been assessed with a potential of more than 10 million metric tons of REEs available within the US [10]. These lanthanides could be recovered from multiple steps of the coal product chain, as for example, from the fly ash from power generation [11]. Some of the current technologies used for extraction of REE are solvent extraction, ion exchange and precipitation, with solvent extraction accepted as the most appropriated technology [9].

Most NF membranes made by interfacial polymerization (IP) are intrinsically negatively charged, due to hydration of non-reacted acyl groups from the trimesoyl chloride (TMC) becoming carboxylic acids. The design of positively charged nanofiltration membranes has been of great interest for their potential to improve selectivity of multivalent cations, by effects of Donnan exclusion mechanism [12–20]. Non-interfacially polymerized positively charged NF membranes have been successfully created with improved selectivity. Different approaches, such as crosslinking and quaternization of amine groups using p-xylylene dichloride (XDC) [12–14], or UV grafting of quaternary amine groups [15,16] have been used. However, these non-IP methods required longer reaction times than their IP counterparts and may face limitations for scaling up. On the other hand, interfacially polymerized positive membranes have also been created, most of them consisting of the addition of primary, secondary and/or tertiary amines [17–20], allowing some of the amine groups to react with TMC, meanwhile allowing unreacted groups to contribute to form positive charges. Monomers with amine groups, such as ethylenediamine and piperazine (the amine most commonly used for synthesis of NF membranes) normally just have a role as crosslinker. However, polymers with amine groups offer more options for leaving unreacted amine groups that can serve as positive charges in the NF layer. This can also be attributed to steric effects from the bulky polymer, where TMC encounters more limitations to reach and react with all the amine groups. Hyperbranched polyethyleneimine (PEI) is a polyelectrolyte that has been used for creation of positively charged membranes [17,19] and also has been used for layer-by-layer assembly of membranes [21]. Another polyelectrolyte is polyallylamine hydrochloride (PAH), which also has been used for layer-by-layer assembly [21–24], and has been found to be used with 1,3-benzenedisulfonyl chloride [20] for interfacial polymerization.

The transport mechanisms of ions through nanofiltration membranes have been evaluated as an initial mass transfer effect called concentration polarization, followed by the partitioning of ions from the aqueous solution into the polymeric matrix, and then the transport through the nanofiltration active layer, which is modeled by the extended Nernst-Planck equation [1,2,25]. A broadly accepted model for describing the whole ionic transport is the Donnan steric pore model and dielectric exclusion (DSPM-DE). Here, partitioning of ions encounter steric (size), Donnan (charge) and dielectric exclusions (mostly associated to the Born solvation energy equation). Furthermore, the main chemical potentials acting on the ionic transport are concentration gradients, electrical potential, with additional convective coupling associated to the solvent transport. Even though this model well describes the membrane rejection, it requires the use of four unknown parameters (effective active layer thickness, pore radius, dielectric constant within the pore and volumetric charge density). These parameters can be approximated through different approaches and/or can be fitted through experimental data, although no accurate values can be easily measured due to the atomic length scale of the system being analyzed [26]. Moreover, solutes sizes are affected by water solvation [27–29] and hydration radii may differ significantly from ionic or Stokes radii (mostly used for consistency throughout the model). These conflicts are still limitations of the model and present a challenge for accurate assessment of the ionic transport.

In this study, the synthesis of a more positively charged NF membrane for the application on the selective separation of lanthanide cations over sodium cations in aqueous solution, and its fundamental understanding is investigated. The objectives of this research are: (1) Introduction of basic functionalities on the NF layer by adding primary amine groups from polyallylamine hydrochloride (PAH) using rapid interfacial polymerization with trimesoyl chloride; (2) Analyze the impact of the addition of the PAH molecules on the surface properties of the polymerized NF layer; (3) Evaluate the stability of both negatively and positively charged NF membranes for separating lanthanides from aqueous solutions under different operating conditions; (4) Use the Donnan steric pore model with dielectric exclusion (DSPM-DE) for elucidating the differences in the transport mechanism between sodium and lanthanides through NF membranes.

2. Experimental

This section brings detail information about the experimental procedures performed in this research. This includes the membranes synthesis, characterization, and performance, along with the analytical methods and materials used.

2.1. Materials

A commercial ultrafiltration (UF) membrane PS35 was obtained from Solecta membranes (formally Nanostone Water, Oceanside, CA). For interfacial polymerization (IP) synthesis of the polyamide (PA) thin film layer, Piperazine (PIP, 99%) anhydrous was purchased from Spectrum (Gardena, CA); Polyallylamine hydrochloride (PAH, MW~15,000, 95%) was purchased from AK Scientific (Union city, CA); Trimesoyl chloride (1,3,5-Benzenetricarbonyl chloride, TMC, 98%) was purchased from Millipore Sigma (Darmstadt, Germany); ISOPAR-G technical grade was purchase from Univar (Downers Grove, IL). For zeta potential, total organic carbon and inductively coupled plasma (ICP) studies, ASTM type 1 water from RICCA Chemical (Arlington, TX) was used.

For testing the performance of the synthesized NF membranes, the rare earth elements (REE) lanthanum (III) chloride anhydrous (LaCl3, 99.9%) and neodymium (III) chloride anhydrous (NdCl3, 99.9%) were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). Calcium chloride dehydrate (ACS grade) was purchased from BDH (Radnor, PA), and sodium chloride (ACS grade) purchased from VWR (Solon, OH). As neutral organic compound used, meso-erythritol (C4H10O4, MW=122.12 g/mol, ≥99%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Fabrication of negatively and positively charged nanofiltration membranes

Interfacial polymerization (IP) reaction was developed under amine - acyl chloride reaction (nucleophilic acyl substitution of acid chloride). Two types of NF membranes were synthesized, where the amine group was the modified factor: one NF membrane consisted of traditional piperazine (PIP) chemistry, and the second one was a mixture of PIP and polyallylamine hydrochloride (PAH) (Figure 1). First, an aqueous solution containing the amine group (PIP or PIP/PAH) was created, containing a total of 1.4%wt amine groups (1.4% PIP or 1.0% PIP and 0.4% PAH) in a 500 mL total solution with DI water (dissolved by stirring for less than 10 minutes). Secondly, a 500 mL organic solution was prepared out of 0.14%wt of trimesoyl chloride (TMC) in ISOPAR-G, which was intercalated between sonication and stirring to ensure all TMC was dissolved. Each solution was kept inside a 3qt glassware, under constant stirring and with the lid on.

Figure 1.

Schematic of interfacial polymerization process for synthesis of the nanofiltration layer. This process was used for both PIP and chemical compositions in the laboratory. A simplified representation of the PIP/PAH – PS35 thin film composite functional groups is presented at the end.

Ultrafiltration (UF) membranes were tightly tapped (23 cm x 15 cm of active surface membrane area) with 3M masking tape onto rectangular glass plates (shown in Figure 1 with additional picture in Figure SI 1), preparing 8 consecutive plates per batch of solutions. Each plate containing tapped UF membrane was initially submerged in DI water for 1 minute and then thoroughly rinsed with DI water (for removing both final coating treatments as glycerol, and any dust particle). Then, a 9” air-knife (EXAIR – Cincinnati) was used for removing droplets on top of the substrate, and Kimwipes were used for gently remove remaining solution and dust from the plate. Right after, plate-membrane was submerged into the prepared aqueous solution for 15 seconds, then air-knife (at ~6 bar) and Kimwipes process was repeated. Afterwards, plate was submerged in the organic solution for the same 15 seconds, and air-knife and Kimwipes process was repeated once more. Finally, heat post treatment was applied, leaving the membrane-plate in a convective oven for 12 minutes at 70 °C. Membranes were cut off the plate and stored dry for following analysis.

A summary description with the denomination of the synthesized NF membranes in this study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Synthesized NF membrane denomination

| NF membrane denomination | UF Membrane Support | Amine groups used for interfacial polymerization | Acyl group in organic solution |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| PIP - PS35 | Piperazine (PIP) | ||

| PS35 | PIP and Polyallylamine | Trimesoyl chloride (TMC) | |

| PIP/PAH - PS35 | hydrochloride (PAH) | ||

2.3. Characterization

A K-Alpha X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) from Thermo Scientific was used for measuring the atomic composition of the thin NF layer, through information of the bounding energies on the polymeric material. Flood gun and Al Kα X-ray monochromator were used. Moreover, 3 to 2 different areas of each membrane were analyzed for calculation of the average and the standard deviation of each element analyzed.

The membranes’ topography was characterized through the surface roughness using an atomic force microscope (AFM) Quesant Instrument Co. Surface roughness was measured under tapping mode, thus obtaining the root-mean-squared (RMS) and the average height. 3 areas of 10×10 μm from each membrane’s surface were randomly selected and measured.

The membrane surface morphologies of the porous support and the synthesized NF membranes were evaluated using a FESEM (FEI Helios Nanolab 660). Membranes were left in water over night and then dried for 3 hours in a convective oven at 30 °C. No metal sputtering was applied, beam deceleration and immersion mode were used, and images at different magnifications were captured.

The membranes’ water contact angle was measured using a drop shape analyzer Kruss DSA100, equipped with a high definition camera, by sessile drop technique. At least 6 different areas of each membrane were analyzed, and 20 contact angles were measured within 10 seconds. Final reported value represents the averaged measured over time and considering the 6 areas measured. All measured membranes were rinsed with DI water over night and then dried at 30°C for 3 hours.

A few different approaches for relating to membranes’ surface exist, although there is no analysis that exactly measures the surface charge in a direct and easy way. One example is binding of ion probes, such as silver [17] or other compounds, and another example is surface zeta potential measurements by an electro kinetic analyzer. The first example consists of measuring carboxyl group density, and different experimental and analytical approaches exist for calculating this [17–19]. On the other hand, surface zeta potential is a parameter that describes the electrical potential at the shear plane on the electrochemical double layer formed between the membrane and the solution in contact with it. This relates to the surface net charge (potential), pKa and other characteristics throughout different pH, concentrations, and other variables in an easy and fast fashion. In recent literature, it has been shown that the calculation of surface zeta potential of porous materials from the Helmholtz-Smoluchowski relation using an electro kinetic analyzer are impacted by porous conduction and streaming current, and therefore new theoretical approaches have been proposed for calculating surface zeta potential from streaming potential and streaming current measurements [20–22]. Hereby, demonstration of differences in surface zeta potential between synthesized NF membranes is shown to be true by using H-S approach, or by using streaming potential data from instrument through the newest theory approach.

An Electrokinetic Analyzer SurPASS from Anton Paar was used for measuring the streaming potential or streaming current. An adjustable gap cell was used, synthesized NF and UF membranes were taped with double sided tape to the sample holder and a 100 μm channel was left between them. Measurements were taken through various pH levels (divided in two halves, one acidic and one basic, using the automatic pH titration mode). ASTM type I water was used for preparing a 1 mM KCl electrolyte solution (similar concentration to single salt rejection experiments), and 0.05 M HCl and NaOH solutions were used for titrating the KCl solution. Four data points were registered per pH (automatically) and information was extracted, averaged and statistical error obtained. Calculation of zeta potential is explained in more details in Results and discussion section.

2.4. Analytical methods

An inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) Agilent 7800 was used for analysis of concentrations of ions in solution for both mixtures and low concentrations. ASTM type I water with 2% HNO3 was used for standard preparations, internal standard solutions, and rinsing solutions. Samples measured were kept at the same 2% HNO3 matrix.

A total organic carbon analyzer TOC-5000A from Shimadzu was used for measuring the inorganic carbon (IC) and the total carbon (TC), and thus calculating the total organic carbon (TOC) of the aqueous solutions obtained from the neutral organic compounds rejections. A high sensitivity TC catalyst was used for filling the TC combustion tube. ASTM type I water was used for sample generation and calibration curve preparation.

A conductivity meter Orion Star 212 from Thermo Scientific™ and a DuraProbe™ 4-Electrode Conductivity Cells (with a range: 1μS/cm to 200 mS/cm, and cell constant 0.475 cm−1) was used for measuring single salt concentrations. Calibration curves for salt tested were performed, with linear regressions (R2>0.9998).

2.5. Membrane performance evaluation

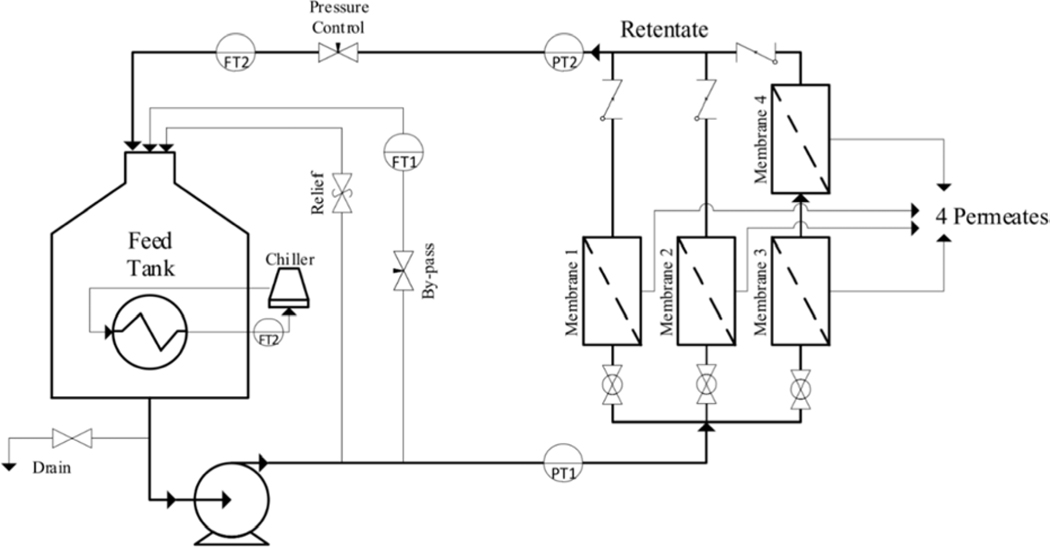

Various membrane performance experiments were tested in a Sterlitech™ Membrane Test Cell System (WA, USA) (diagram shown in Figure 2) with two CF016 cells (membrane 1 and 2) in parallel, and a third cell (CF042) in parallel configuration (membrane 3), with a final fourth membrane cell (CF042) in series (membrane 4) with membrane 3. In total, this gives 125.2 cm2 (19.4 in2) of membrane surface area being tested. This also offers a more reliable statistical analysis, reported in the standard deviation of both the permeate flux and the rejection of the membranes tested. Particularly, for recovery analysis a batch stirred filtration cell was used (see Figure SI 2), Sterlitech P/N 4750, with a membrane active area of 14.6 cm2 (2.26 in2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the Sterlitech™ Membrane Test Cell System used for crossflow analyses

All membranes were used once for either a whole single salt rejection experiment (fresh membranes for each salt), or a synthetic mixture of salt experiment (both concentrations), or an experiment at different pH values. Synthesized membranes samples were selected from different plates, thus providing the repeatability of the fabrication process. All membranes were compacted for at least 3 hours initially under their maximum pressure reported in the water permeability plots (see Figure SI 3), measuring their water permeability at the end of that time. Then salt(s) was(were) added (completely dissolved), and at least 3 hours passed before each respective collection of samples (around 30 mL in a 50 mL centrifuge tube), changing either the pressure or the concentration (depending on the experiment). Finally, system was drained and rinsed two times with DI water, where in the last one after 3 hours for stabilizing the system water permeability was calculated.

NaCl, CaCl2, LaCl3 and NdCl3 were use as model salts, since they keep same Cl− as counterion, and therefore rejection was affected mostly by the cation size and charge change (as well as dielectric characteristics within the pores), which are the main partitioning terms for ions into nanofiltration membranes [1]. 6 liters of DI water with 1mM of each single salt were tested at different pressures, maintaining the same permeate flux and thus similar convective coupling (Jv) of ions with water throughout the thin film composite. Low concentration was used for avoiding fully surface charge complexation of ions with carboxylic acids and amine groups, and its consequent diminish of the NF thin layer surface charges. The lower the permeate flux, the lower the impact on the ion transport equation, and both diffusive and electrical potential gradients may prevail. More details about membranes performance experiments are presented in SI.

Process reproducibility is a critical aspect for scaling up a laboratory scale technology. In this study, as it was mentioned in the interfacial polymerization section, eight plates were casted per batch of solutions created. This number was determined after several synthesis and adjustments until reliable results were reached. Higher number of reuses could be further investigated. Moreover, each NF membrane synthesized (“plate”) has enough area for taking off around 4 samples (far away enough from the edges of the tape) to be tested in the crossflow experiments and other membrane testing units. This results in enough samples for assessing the overall reproducibility of the membrane synthesis process in a batch to batch and within batch statistical error. Water permeabilities were assessed as a simple and transversal method of comparison.

The diffusive transport of sodium chloride and lanthanum chloride were measured using an automated in-line ILC07 system from PermeGear. This consisted of 7 flow diffusion cells arranged in parallel configuration, loaded with the individual feed (donor) solutions of NaCl and LaCl3 and the respective membranes tested. A flow rate of 75 μL/min of type I water was provided by a high precision peristaltic pump, and donor chamber volume of 800 μL with the respective solutions. 4 collector samples were obtained for each cell at every 3 hours, giving a total of 12 hours run. Concentrations on the collector samples were measured using ICP-MS. More details on the system and calculations are presented elsewhere [30].

3. Modeling

This section focuses on the description of the transport model used in this work (Donnan steric pore model with dielectric exclusion – DSPM-DE), its application in this study, and the solving approach.

The DSPM-DE [1,2] was used for modeling the transport of NaCl and LnCl3 (lanthanide chloride) through the synthesized NF membranes. This model includes partitioning of ions due to steric, Donnan and dielectric exclusion, along with the extended Nernst-Planck equation for the transport through the membrane domain (main Equations are presented in Section 4 of the SI). Addition of the dielectric exclusion term has allowed the fitting volumetric charge densities (Xd) smaller in magnitude compared to DSPM alone [1,31], which permits better assessment of positively charged NF membranes and their Donnan exclusion differences to negatively charged NF membranes. The dielectric exclusion term was calculated using the Born model for estimating the solvation energy barrier of the ions [1]. Several studies have analyzed this model [32] and have successfully fitted experimental data of negatively charged NF membranes [33–35]. For solving this model, a finite difference approach was used, similar to the one described by Geraldes V and Brites A. M. [25], with the difference that the nonlinearity of the system was kept. MATLAB R2020a was used as software and the fsolve function was used for solving the nonlinear system of equations. Finally, fitted parameters from experimental data were obtained helped by the least square difference and fmincon function.

The typical unknown variables in this model were assessed as follow. The NF membrane pore radius (rp) was modeled separately using an uncharged solute [1,2] (Erythritol −122 Da) as explained in the section 7 of the SI. The effective active layer thickness to porosity ratio (Δx/Ak) was correlated by linking solvent velocity with membrane thickness through the Hagen-Poiseuille-type relationship [1,36], by using the water permeabilities experimental results of the membranes. For the case of dielectric constant within the pore (εp) and the volumetric charge density (Xd), this study focuses on the comparison of lanthanide cations relative to sodium cation, therefore single salt rejection of sodium chloride at different permeate fluxes were fitted to model and both εp and Xd were optimized. Further discussion about model prediction accuracy was also included, and validation of model was presented in SI.

4. Results and discussion

In this section, the results of the synthesized membranes characterization and their performance are presented. First, we provide the elemental composition through X-rays photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and other surface characterization techniques, including surface zeta potential and estimation of the modeled pore radius, for comparing both synthesized nanofiltration membranes and validating the addition of PAH with its basic functionalities. Secondly, we show the water permeabilities, single salt solution rejections and reproducibility of the synthesized membranes for corroborating their application in nanofiltration processes. Finally, we present an evaluation of lanthanides rejection under various operational conditions, including mixtures (at low and high ionic strengths), water recovery selectivity, and pH experiments.

4.1. Chemical composition of thin interfacial layer

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was used for extracting elemental composition of the top ~10nm, thus obtaining an overall idea of the NF layer surface’s composition (Table 2). Porous UF support (PS35), and synthesized PIP – PS35 and PIP/PAH – PS35 membranes were analyzed. Porous support was well identified by its characteristic presence of sulfur (from its polysulfone composition), and no nitrogen was expected to be in the main composition. On the other hand, the NF layers contained their characteristic nitrogen, but not sulfur. Table 2 clearly presents this distinction.

Table 2.

Elemental composition obtained from XPS surface analysis for the porous support and the synthesized NF membranes

| Membrane | C (%) | O (%) | N (%) | N:O |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PS35 | 81 ± 0.7 | 14 ± 0.4 | 0 (Sulfur: 5 ± 0.3) | - |

| PIP - PS35 | 72 ± 0.1 | 16 ± 0.3 | 12 ± 0.4 | 0.80 |

| PIP/PAH - PS35 | 69 ± 0.1 | 17 ± 0.5 | 14 ± 0.3 | 0.83 |

Elemental composition approximated to the integer. N:O ratio calculated with decimal values.

Specifically focusing on the two created nanofiltration layers, 2% increase in “N” was observed in PIP/PAH – PS35 versus PIP – PS35, which means there was higher density of bound N in the polymeric top layer, coherently to the addition of amine groups from PAH polymer. It is important to keep in mind that a high degree of polymerization between PAH and TMC can keep the number of unreacted nitrogen as low as in the PIP chemistry, and consequently same amine groups may be available for contributing with positive charges. Therefore, PAH ideally should present both some degree of crosslinking and some degree of entanglement, allowing mechanical strength but, at the same time, not fully crosslinking its amine groups (weak bases). Selected PAH polymer, as molecule for integrating positive charges, is long and steric effects may contribute to both difficulties of TMC reaching all amine groups, and at the same time, to entangle within this quickly formed polyamide structure. N:O ratio was calculated and presented in the last column of Table 2, which means in some degree the availability of nitrogen to contribute as a positive charged group versus oxygens to crosslink the nitrogen or to contribute as negatively charged groups (carboxylic acids). Liu Y. et al. [37] varied PIP concentrations and, it was found that the higher the O:N ratio the more negatively charged the membranes were found to be, supporting the expected trend. An increase from 0.8 to 0.83 in the N:O ratio, with a standard deviation of 0.03 in both cases was not a statistically significant change, and so a net surface charge modification cannot be predicted through the elemental composition of the NF layer.

4.2. Surface roughness and hydrophilicity

Surface roughness, hydrophilicity and surface charge are just some of the properties and the ones that were reviewed in this study. Polyallylamine hydrochloride (with a MW ~15,000) is a long polymer chain, with a root mean square (RMS) end-to-end distance around 4.8 (nm) (which represents its coiled nature and includes bonds rotating freely about a fixed bond angle, calculation on section 4 of the Supplementary Information). Compared to the monomers used in the classic interfacial polymerization for NF membranes (TMC and PIP), PAH has a considerably bigger size and thus impacts surface roughness and potentially other physical properties.

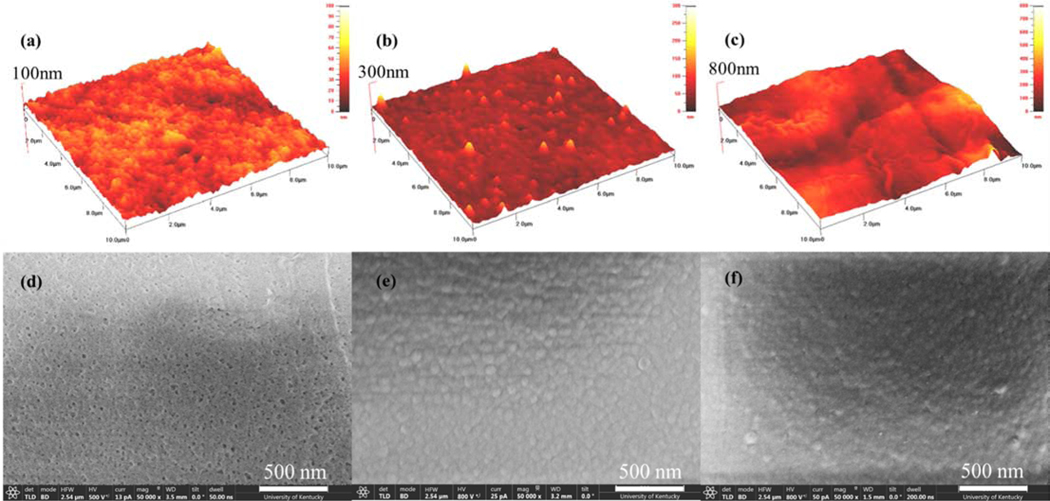

In order to show the impact of the addition of PAH on surface roughness (Figure 3 a, b and c), an atomic force microscope was used. It was first observed that an increase from the porous support to the interfacially polymerized PIP – PS35 membrane was obtained, and that further increase was found for PIP/PAH – PS35, as it was expected from the addition of the long chain PAH molecules. Table 3 summarizes RMS roughness and surface height values. Furthermore, a scanning electron microscope (Figure 3 d, e, and f) was used for extracting information about the porous support and NF layer surface features. Figure 3 (d) clearly presented the porous characteristic of the UF membrane. For the PIP-PS35 membrane, it was observed that polyamide layer with globular shape covered the porous support surface. For the case of the PIP/PAH-PS35 a similar shape of polymer layer to the PIP-PS35, although semi coverage of the surface is appreciated, revealing some porous support features. Figure SI 4 (e) presents an 80,000x magnification image of PIP/PAH-PS35 for an easy observation of this hybrid surface features observed. This can be related to a reduction in reactivity due to the long PAH chains and its steric effects. Additional SEM images at higher and lower magnitude are presented in Figure SI 4 for complementary analysis.

Figure 3.

Surface characterization of roughness from AFM (a, b, and c) and imaging from SEM (d, e, and f) at 50,000x magnification. (a, d) Porous support, and synthesized (b, e) PIP - PS35 and (c, f) PIP/PAH - PS35 NF membranes.

Table 3.

Surface roughness RMS (root-mean-square), average height and water contact angle of the porous support and the synthesized NF membranes

| Membrane | RMS Roughness (nm) | Average Surface Height (nm) | Water contact angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| PS35 | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 35.9 ± 3.6 | 71 ± 0.8 |

| PIP – PS35 | 15.3 ± 2.1 | 55.9 ± 13.1 | 43 ± 3.1 |

| PIP/PAH – PS35 | 50.9 ± 16.3 | 139.5 ± 62.7 | 72 ± 2.0 |

The overall hydrophilicity of the NF membranes is related to both the carboxylic acid and amine groups present in the NF layer, and it is altered by the hydrophobic domain from the organic backbone. The addition of PAH affects all the before mentioned, the addition of positive charges from its unreacted primary amines, and from the reaction with TMC which can leave unreacted acyl groups becoming carboxylic acids in contact with water. For measuring the overall hydrophilicity of the membranes in this study, water contact angle was used. Measured values from the porous support and the synthesized NF membranes are presented in Table 3. PIP – PS35 NF membrane showed some degree of hydrophilicity (contact angle 43°) as it has been shown in literature [37]. However, water contact angle of PAH modified membrane went up to 72° (water contact angle stability over time is presented on Figure SI 5). This considerable increase would not be predicted considering a potential decrease in the degree of polymerization from the addition of PAH and its steric effects, increasing the formation of carboxylate groups. Further validation of this trend was performed by additionally testing new synthesized PIP and PIP/PAH membranes on top of an additional porous support, an ultrafiltration (UF) polyethersulfone (PES) membrane used for the synthesis of gas separation membranes, provided by Honeywell UOP (section 7 of SI, Figure SI 5 (b)). Studies on layer-by-layer deposition technique using PAH [24,38] has shown an increase in the water contact angle of the exposed PAH layer, with values around 60–80. Finally, it is believed that semi-hybrid surface features observed on the PIP/PAH-PS35 from SEM images may indicate that more hydrophobic properties from the porous support (Table 3 and Table SI 1) could have been expressed in the PIP/PAH-PS35 membranes.

4.3. Modeled nanofiltration pore radius

In order to evaluate the impact of PAH on the nanofiltration layer’s structure, as well as for further modeling of ionic transport, the modeled pore radius (rp) was calculated using the uncharged solute rejection approach (as presented in SI section 7), with erythritol as modeled solute (rs=0.268 nm). Figure SI 6 presents the experimental results and the fitted model. We found no major differences between both PIP-PS35 and PIP/PAH-PS35 synthesized NF membranes’ pore radius was found, with optimized values presented in Table 4, within the range of commercial and lab-made PIP-based polyamide NF membranes [39]. It could have been expected that large PAH molecules could have reduced the reactivity or have decreased the tightness of the polymer network, which was not the case from the obtained modeled pore sizes. Other validation methods can be used for corroborating this finding, such as positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy (PALS) [40] and relate it to the free volume of the dense layer. For the scope of this study, the separation of sucrose (with a molecular radius of 0.471 nm [41]) was evaluated. Expected high exclusion was observed for both membranes, with rejection values of 99±1% and 97±1% for the PIP-PS35 and PIP/PAH-PS35 membranes, respectively. It is also important to recall the water permeability coefficients presented in Figure SI 3 with their stability presented in Figure SI 10, which values were not statistically different. Modeling the NF membrane as a porous membrane as it is the case of the uncharged solute rejection approach, or the Donnan steric pore model with dielectric exclusion for the transport of ions, the water permeability coefficient is directly proportional to the pore size of the membrane using the Hagen-Poiseuille (H-P) relation. Therefore, if the membranes kept a relatively similar thickness, it would further justify the similitude of the calculated pore sizes. For the case of polyethyleneimine (PEI) with TMC positively charged NF membranes Yen-Che Chiang et all [17] found an increase of the pore size relative to other diamine groups used (using H-P equation and molecular weight cut off measurements). Their PEI/TMC membrane performed both considerable higher water permeability coefficients and decreased rejection of polyethylene glycol molecules, which is not the case for the PIP/PAH-PS35 membranes synthesized in this study, and then the almost constant modeled pore size become plausible.

Table 4.

Modeled pore radius of the synthesized NF membranes

| Synthesized NF membrane | Modeled pore radius (rp) (nm) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| PIP-PS35 | 0.45 |

| PIP/PAH-PS35 | 0.44 |

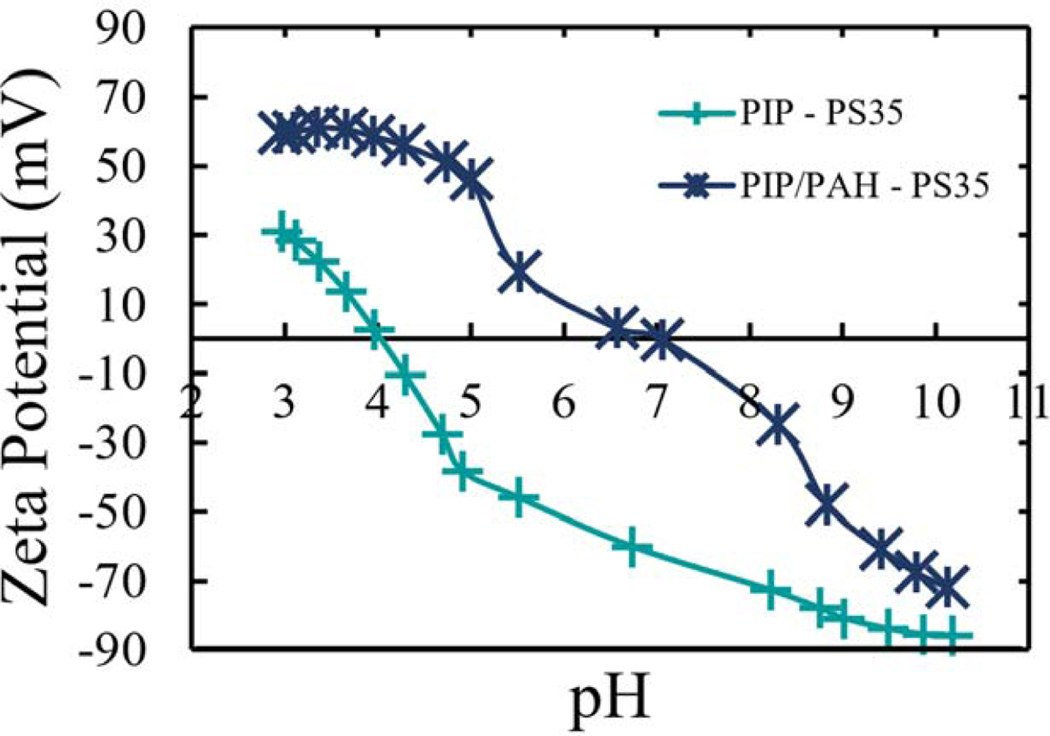

4.4. Impact of polyallylamine hydrochloride on surface electrochemical properties

In order to prove not just the addition of the amine groups, but the increase in the net surface positive charge, surface zeta potential was utilized. In Figure 4, the surface zeta potential calculated by using the Helmholtz-Smoluchowoki relation (Equation S22 and Table SI 2) is presented. This representation carries error from porous backing effects [42–44], although qualitative acidic behavior for the PIP-PS35 membrane is observed (in concordance to having mostly carboxylic acid functional groups), and a more amphoteric-like shape is presented in PIP/PAH-PS35 membrane (in this hybrid surface with carboxylic acid and amine functional groups). Moreover, PIP-PS35 have an isoelectric point (IEP) around 4 which is in the range obtained in negatively charged thin film composites [13,18,45,46] and slightly more negative compared to the surface zeta potential magnitude obtained at pH~7 by Yan-ling Liu et al. [37] which can be attributed to shorter submersion times in the present study, leaving more unreacted TMC. On the other hand, the PAH modified membranes presented a higher IEP (around pH 7), which was expected from the addition of positive groups. The isoelectric point of some positively charged NF membranes found in literature range between pH 5.2–10.5 [12,13,17–19,45,47–49], with an average of polyethyleneimine (PEI) membranes’ IEP of 6.3 [13].

Figure 4.

Zeta potential calculated by Helmholtz-Smoluchowoki equation. Parameters, and values were obtained from Electro kinetic analyzer are presented in section 9 of Supplementary Information

The robustness of the enhance in the surface positive charge by integration of the PAH was further validated. The synthesis of both PIP and PIP/PAH membranes was performed on top of an additional porous support (same as the ones used in contact angle validation). Results were consistent (Figure SI 7) with the PS35 porous support. Even slightly higher IEP was obtained (7.5), and difference in IEP by 2 pH values.

In Table 5 pKa of the functional groups added as in their monomeric conditions are presented. These pKa could be considered if just surface groups are involved in zeta potential measurements and electron density distribution in their polymeric form is not highly affecting their pKa. Although, it has been shown that carboxylic acid groups within the polyaromatic amide thin-film composites behave following a two pKa fitted model [53,54], with values around pH 5.2 and 9 (pKa1 and pKa2 respectively), associated to the impact of the dielectric constant within the constrained spaces inside the polymeric matrix increasing the dissociation energy. Opposite effect is mentioned for the amine groups which would tend to decrease the pKa [53]. Considering both, characteristics from the surface and bulk (with lower intensity) of the NF polymeric layer emerging in this measurement, pKa values for zeta potential may fall between 3.12 and 5.2, with some potential second pKa around 9.

Table 5.

pKa of the functional groups present in the synthesized NF membrane layers at monomeric conditions

| Functional Group | pKa | Reference |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Trimesic acid (pKa I) | 3.12 | [50] |

| Trimesic acid (pKa II) | 3.89 | [50] |

| Trimesic acid (pKa III)a | 5.20 | [50] |

| Secondary amine in piperazine (pKa I) | 9.73 | [51] |

| Primary amine (H(CH2)2NH3+) | 10.67 | [50] |

| Protonated amidesb | Negative | [52] |

Shown as a reference, not present in NF layer.

Protonated amide groups present a pKa with negative values (will be found neutral in the evaluated pH range (zeta potential), and in typical NF pH operation conditions).

4.4.1. Demonstration of enhanced increase in surface zeta-potential

A side objective in this work is to provide information of the increase in positive surface potential taking away the porous support effects, bringing further validation to the integration of positive charge into the membrane. For doing this, recent approaches in literature [43] on how to model the tangential streaming potential and streaming current were considered. Moreover, the use of a single porous support (commercial PS35 from Solecta), for the synthesis of the two NF membranes in this study, allowed an arithmetic manipulation and terms subtraction. Demonstration of the calculation of a “real” increase in the surface zeta potential from the synthesized PIP-PS35 to the PIP/PAH-PS35 NF membranes is presented in the section 8 of the SI. Calculation of the difference in the surface zeta potential between the two synthesized membranes was calculated from the measured streaming potential and the overall system conductance values, in addition to parameters from the system. Figure SI 8 shows the plot of the “real” increase in surface zeta potential, with an increase in throughout the pH measured (3–10), and with a maximum at pH~5. Differences at pH 3 and pH 10 may provide information about the increase on amine groups (positive charge) and the decrease in carboxylic acid groups (negative charge), respectively.

4.5. Overall membrane performance

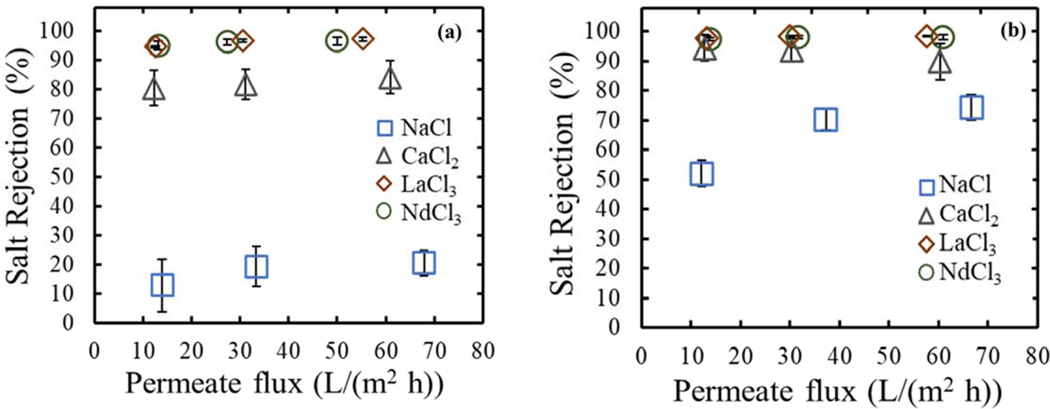

In order to evaluate the separation performance of the synthesized nanofiltration membranes, both water permeability coefficient and rejection of different salts with same counterion (chloride) were studied. First, water permeability coefficients (A) were calculated from the slope of water flux (Jw) versus pressure (P) obtained from the crossflow membrane system presented previously. Difference of the A coefficient between PIP-PS35 and PIP/PAH-PS35 membranes was found to be within statistical error (and calculated APIP-PS35 = 9.1 (L/m2 h bar); APIP/PAH-PS35 = 9.0 (L/m2 h bar)) as presented in Figure SI 3. Moreover, for verifying reproducibility and membrane stability in crossflow operation, water permeability was calculated before and after operation of single salt solutions, with fresh membranes each single salt solution used. Figure SI 10 presented good reproducibility of the synthesized nanofiltration membranes, with variations in the A coefficient within statistical error.

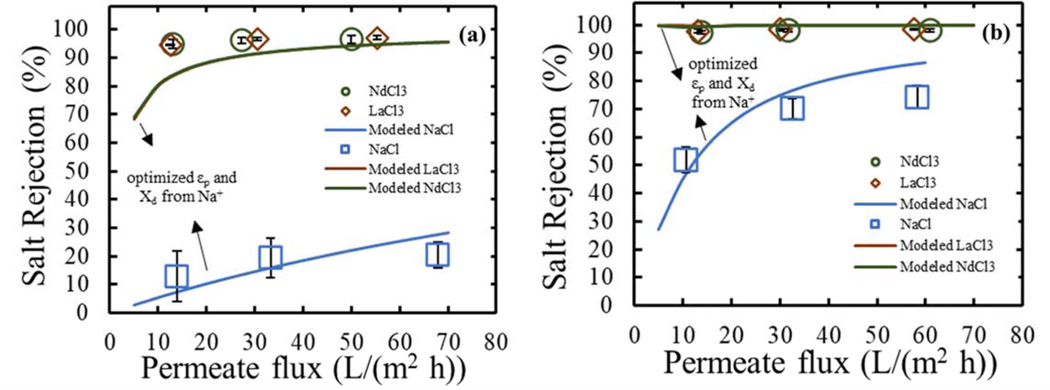

Furthermore, an evaluation of the impact of the addition of PAH on the NF membranes’ selectivity was assessed by rejection of salt solutions (NaCl, CaCl2, LaCl3 and NdCl3). PIP/PAH- PS35 achieved a slightly increase in rejection of lanthanides (La3+ and Nd3+) relative to the PIP-PS35 membrane, although an unexpected increase in sodium and calcium ions was also obtained. This was indicative that the addition of PAH may not just have added positively charged groups (and therefore modified the volumetric charge density), but also other membrane characteristics that affect the transport of ions through the NF membrane. As explained more in details in the upcoming section “Separation mechanism differences between sodium and lanthanides cations – Modeling section”, the dielectric exclusion term was also found to be affected, revealed using the Donnan steric pore model with dielectric exclusion (DSPM-DE). Figure 5 summarizes the rejections of both synthesized NF membranes over different permeate fluxes. With obtained rejections as high as 97±0.3% and 98.5±0.8% for LaCl3, and 20.5±9.0% and 74.5±4.4% for NaCl, for PIP-PS35 and PIP/PAH-PS35, respectively. Divalent cations (Ca2+ or Mg2+) are normally used for testing negatively and positively charged membranes. Rejection of calcium chloride in the order of 93% for the PIP/PAH-PS35 NF membrane is comparable to other positively charged NF membranes from the literature (between 87 and 96%) [12]. Na+/Ca2+ selectivity (calculated as ) PIP/PAH-PS35 were comparable to PEI positively charged membranes (Na+/Mg2+ selectivity) [13]. Consistent values throughout the different permeate fluxes were obtained for the PIP-PS35 membrane around 4.5. This was not the case for the PIP/PAH-PS35 membrane, where the Na+/Ca2+ selectivity varied from 8.8 at the lowest permeate flux measured, down to 2.55 at the highest permeate flux measured. Meaning that this new PIP/PAH-PS35 may present promising selectivity for a process at low permeate flux operation. The limit at which this low permeate flux occurs can be measured in a diffusion cell, extracting the diffusive permeability of the salts [30]. Preliminary results (Figure SI 11) showed that sodium permeabilities of both membranes were similar, with values of 2 ∙ −10 (m/s) and 2.2 ∙ −10 (m/s) for PIP-PS35 and PIP/PAH-PS35, respectively. Although, a major difference was found in the lanthanum, with a significant drop in the permeability of lanthanum at diffusive conditions, with a value of 1.4 ∙ −10 (m/s) for the PIP/PAH-PS35 membrane, versus 1.9 ∙ −10 (m/s) for PIP-PS35 an order of magnitude higher. This could explain the potential of this membrane at low permeate flux conditions, in which convective coupling is minimized and both charge and diffusive effects prevail. Finally, Na+/La3+ selectivity of both membranes remained high, although PIP-PS35 presenting higher values (up to 28 at the highest permeate flux) than PIP/PAH-PS35 (up to 22.51 at the lowest permeate flux), which is explained by the high sodium rejection of the synthesized PIP/PAH-PS35 membranes, reducing its selectivity.

Figure 5.

Single salt rejection of synthesized NF membranes over a range of permeate fluxes. Traditional piperazine chemistry (a) and by addition of PAH (b). Analyses were run at 3 different permeate fluxes (similar between each other – 68, 34 and 14 (L/m2 h)), 21 °C, 1mM concentration of sodium chloride, calcium chloride, lanthanum chloride or neodymium chloride salt, pH from water-salt solution (unmodified, NaCl: 6.9, CaCl2: 5.9, LaCl3 and NdCl3:4.1), in the crossflow membrane unit presented previously. Each curve represents 4 new (non-used before) membranes (error bars), after 3 hours of compaction with DI water, and then after the addition of the salt, each pressure/permeate flux point was measured after 3 hours of stabilization. Concentrations were calculated through conductivity measurement. Water permeability of membranes ~9 (L/m2 h bar).

4.6. Evaluation of lanthanides rejection under various operational conditions

4.6.1. Impact of ionic strength on lanthanum selectivity

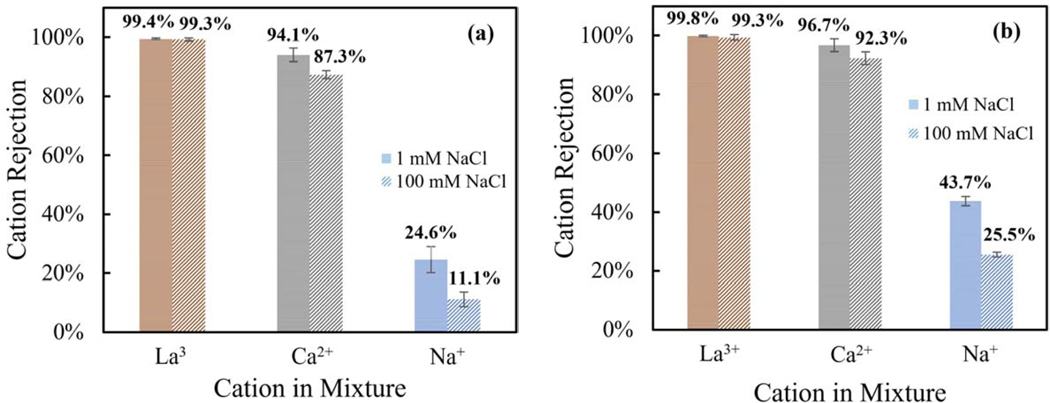

Evaluation of the impact of ionic strength on both positively and negatively charged membranes on lanthanum chloride and its comparison to other chloride salts was performed. At initial conditions of 1 mM concentrations (presented as denser horizontal stripes columns in Figure 6), the rejections of sodium were slightly lower than the rejection where NaCl was a single salt in solution. Moreover, lanthanum and calcium increased relative to their single salt rejections, which can be attributed to selectivity of cationic transport and higher concentration of chloride counterions, letting chloride and sodium pass preferentially. Labban et. al. [55] observed a significant decrease in the rejection of sodium cations when mixture contained divalent cations, relative to the rejection when sodium was the only cation present, which aligns to the findings in this study about selectivity of sodium over multivalent cations. On the other hand, at high NaCl concentration, sodium rejection decreased considerably, and calcium was also compromised in a lesser degree. However, for the case of lanthanum cations, the rejection was not significantly affected by the ionic strength of the feed solution. Average rejections for both PIP-PS35 and PIP/PAH-PS35 remained above 99% at both ionic strength and within standard deviations. This is an important observation, since at high ionic strength the electrostatic interactions should be reduced with consequently reduction in Donnan exclusion, although still exhibiting high lanthanum rejections. Although selectivity is playing a main role, this can mean that size exclusion was the main rejection mechanism for lanthanum rejection, or that other potential strong interactions of lanthanum are reducing its partitioning into the membrane.

Figure 6.

Impact of the mixture of monovalent, divalent, and trivalent cations, and the ionic strength on lanthanum selectivity. Rejection of ions mixture at low and high ionic strengths. 1) horizontally dashed column:1 mM of each salt (NaCl, CaCl2, LaCl3); and 2) diagonally dashed column: 1 mM of (CaCl2 and LaCl3) and 100mM NaCl (by adding 99mM to the previous solution). The analysis was run for the synthesized NF membranes (PIP (a) and PIP/PAH (b)) at 21 °C, pH 4.6 ± 0.4 (std), 47.5 ± 3 (std) (L/m2 h) permeate flux, in the crossflow membrane unit presented in Figure 2. Each plot represents a set of 4 new membranes (just used for the mixture solution), after 3 hours of compaction with DI water, then each concentration was measured (using ICP) from samples taken after 3 hours of stabilization.

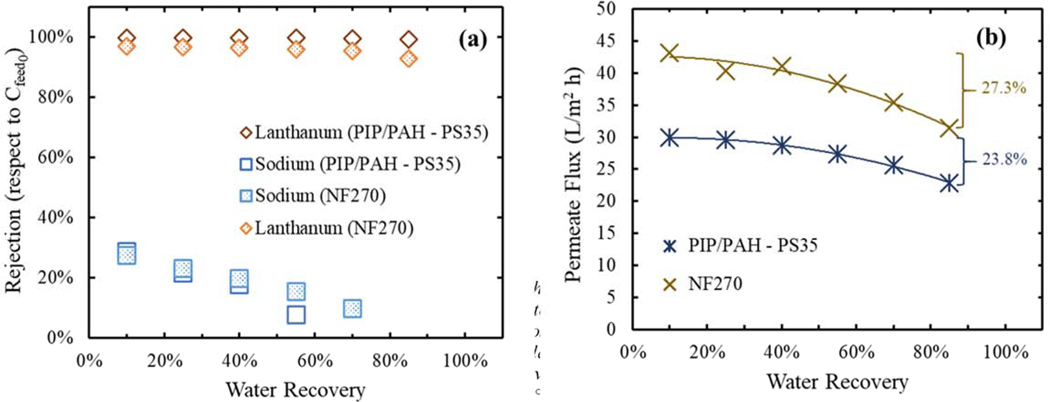

4.6.2. Water recovery effects on selective rejection of lanthanum

The modified PAH NF membrane was tested in a water recovery mode against a benchmark for NF membranes, the commercial NF270 from Dow Filmtec. The NF270 membrane has been used as a standard for NF membranes [33,56] and a summary of some membrane properties are presented in Figure SI 3 and Table SI 3. For initial comparison of this membrane against the synthesized NF membranes in this study, both water permeability coefficient and the NaCl rejection were measured and calculated. Water permeability coefficient was around 18 (L/m2 h bar) and the rejection of NaCl showed to reach a maximum rejection around 50% at permeate fluxes above 100 (L/m2 h).

For the water recovery experiment, a mixture of approximately 1 mM LaCl3 and 30 mM NaCl, representing low concentration of lanthanum in an aqueous source with higher concentration of other ions, was fed to a batch cell (see Figure SI 2) and six samples were taken over the experiment run of both membranes. It was observed in Figure 7 (a) that overall, both PIP/PAH – PS35 and NF270 membranes exhibit consistent selectivity of sodium over lanthanum ions.. However, main differences rely on the sodium rejection decrease over time, and the stability of the lanthanum rejection. Lanthanum rejection of the PIP/PAH-PS35 membrane started at 99.8% and went down just to 99.3%, although NF270 performed an initial rejection of 97% and went down to 93%. Additionally, sodium rejection of the PIP/PAH-PS35 performed a sharp decline over time, where at around 65% recovery it showed close to 0% rejection relative to the initial feed concentration. This means that between the high selectivity of Na+ versus La3+, the ease transport of sodium and chloride ions additionally to the increase of the retentate concentration, makes the concentration in the permeate sample (at 65% recovery) and the concentration initially fed in the system the same.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the Na+/La3+ selectivity between the modified positively charged NF membrane (PIP/PAH – PS35) and the commercial NF270, under water recovery mode in a batch membrane cell. (a) Lanthanum and sodium rejection versus water recovery, (b) decrease of permeate flux due to increase in osmotic pressure. Feed solution with low concentration of lanthanum chloride (~1mM) relative to sodium chloride (~30 mM) simulating conditions of low lanthanum in high aqueous matrixes. Recovery samples taken at 10%, 25%, 40%, 55%, 70% and 85% in average. Samples were measured in ICP. Operational transmembrane pressure of 4.8 bar and 21°C, with unmodified pH=4.75±0.25.

For a high recovery process, a higher Na+/La3+ selectivity would be desirable, allowing the production of a purer concentrated retentate (with less sodium) and at the same time reducing energy consumption, due to osmotic pressure. Even though commercial NF270 membrane exhibited higher permeate flux (due to its higher water permeability coefficient), its lower Na+/ La3+ selectivity was consequently decreasing permeate flux at the end of the operation, due to the osmotic pressure generated by sodium (Figure 7 (b)). This effect could be attributed to differences between both membranes’ properties (pore radius, surface charge and dielectric exclusions). This is an advantage for the synthesized PIP/PAH – PS35 NF membrane over the commercial NF270, since at desired high-water recovery conditions the first membrane generates a purer stream.

PIP-PS35 membrane was also tested under high water recovery conditions. Figure SI 13 (a) summarizes all three membranes, in which PIP/PAH-PS35 was able to quickly respond with a reduction in the sodium rejection, although lower rejection are presented by PIP-PS35 from initial water recoveries, as presented in single salt rejection results. PIP/PAH-PS35 kept the highest rejection of lanthanum throughout the entire recovery run between all three membranes (Figure SI 12 (b). Finally, similar to the case of NF270, PIP/PAH-PS35 was the membrane experiencing the least total loss of water flux (Figure SI 12 (c)).

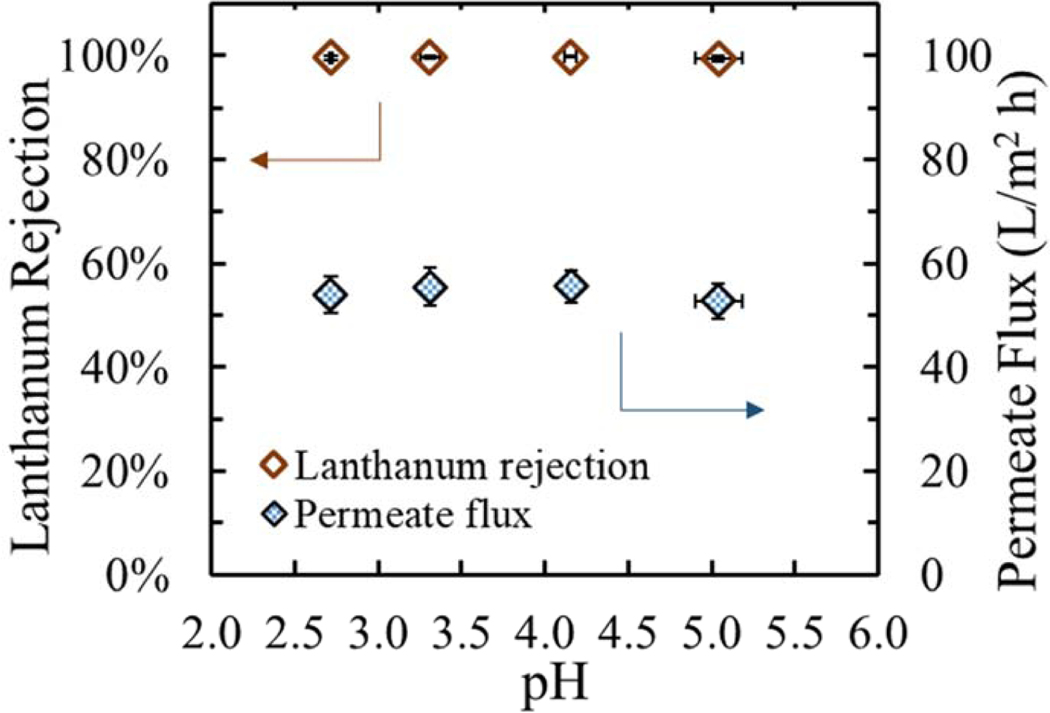

4.6.3. Role of low pH on lanthanum rejection

Lanthanides are present in low pH solutions after leaching extraction from their initial source (such as coal fly ash or mining effluents) [9,57] in which lanthanides are mostly present as [Ln(H2O)9]3+ (pka1=3.00–5.87 depending on what lanthanide [58]) and no complex formation with hydroxide groups exists. For the case of the solid interface, stability of polyaromatic amide membranes at low pH (pH 2–3) [59,60] is a concern since amide bonds can hydrolyze. Also, at low pH carboxylic acids from the NF layer are expected to be mostly protonated, thus changing the surface charge functionality. As presented for the case of different sodium halides [29], the exclusion of ions by Donnan potential effects was dependent on the different pH values measured, and thus shaping the overall rejection. Therefore, in order to evaluate the stability of the synthesized polymeric nanofiltration membranes in a low pH range, the rejection of lanthanum chloride at pHs between 5–2.7 was tested in a crossflow operation mode.

Figure 8 presents the lanthanum chloride rejection and water permeability results of the synthesized PIP/PAH-PS35 NF membranes, from samples taken at pHs 5.0, 4.2, 3.3 and 2.7. Neither lanthanum chloride rejection nor water permeate flux was compromised at any low pH samples, with an average rejection of 99.6% and difference within a standard deviation of 0.6% and permeate fluxes differences also within a standard deviation of 3.7 (L/m2 h). These results are consistent with the surface charge from the zeta potential data, where the positive amine charge stays at lower pH and therefore higher or similar rejections can be expected. Moreover, it proved chemical stability of the synthesized positively charged membranes at those low pH value. Furthermore, PIP-PS35 membranes were tested under a similar experiment, although a higher pH was pursued. High rejection of lanthanum chloride was also achieved at any pH measured, with no significant increase or decrease. Mullett et.al. [46] analyzed a copper mining effluent with multivalent ions, and they found that for a commercial NF270 the rejections of multivalent cations at pH below the isoelectric point presented an increase, associated to the formation of a more positive surface. The water flux of PIP-PS35 presented a decay at higher pHs values (see Figure SI 14 (a)), which is opposite to the expected trend, where at lower pH protonation of carboxylic acids makes a more hydrophobic surface and also lack of charge interactions bring groups closer together, slightly reducing the water permeability (as it is the case for commercial NF270 [61]). Particularly, for pH values above 5.0 the formation of complex [La(H2O)8(OH)]2+ was visible, consistently to the pKa1~5.9 of lanthanum [58]. Consequently, minor increments of pH values per NaOH added into the feed solution were obtained (see Figure SI 14 (b)), and later precipitation of lanthanum on membrane surface was observed (see Figure SI 14 (c)).

Figure 8.

Lanthanum rejection and permeate flux stability at moderated-low pH feed solution. First, 2 hours membrane compaction with DI water, and then LaCl3 was added for creating a 1mM LaCl3 solution (pH=5.0). Reduction of solution pH was achieved with different volumes added of HCl 1 (M). Samples were taken after 2 hours of stabilization, at pH= 5.0, 4.2, 3.3, 2.7; 21°C and P=6.1 (bar). Water permeability of membrane ~9 (L/m2 h bar). Concentrations were measured using an ICP.

5. Separation mechanism differences between sodium and lanthanides cations – Modeling

In this section, we analyze the transport of La3+ and Nd3+ (as model lanthanides) relative to Na+, with same chloride as counterions. First, we use the DSPM-DE from a fundamental perspective, inspecting the role of size and charge under two separate conditions. Then, we analyze the model performance parameters of both the positively and the negatively charged synthesized NF membranes, and their role in predicting the experimental results. Additionally, a discussion about the lack on predicting lanthanides results from the negatively charged membranes is presented.

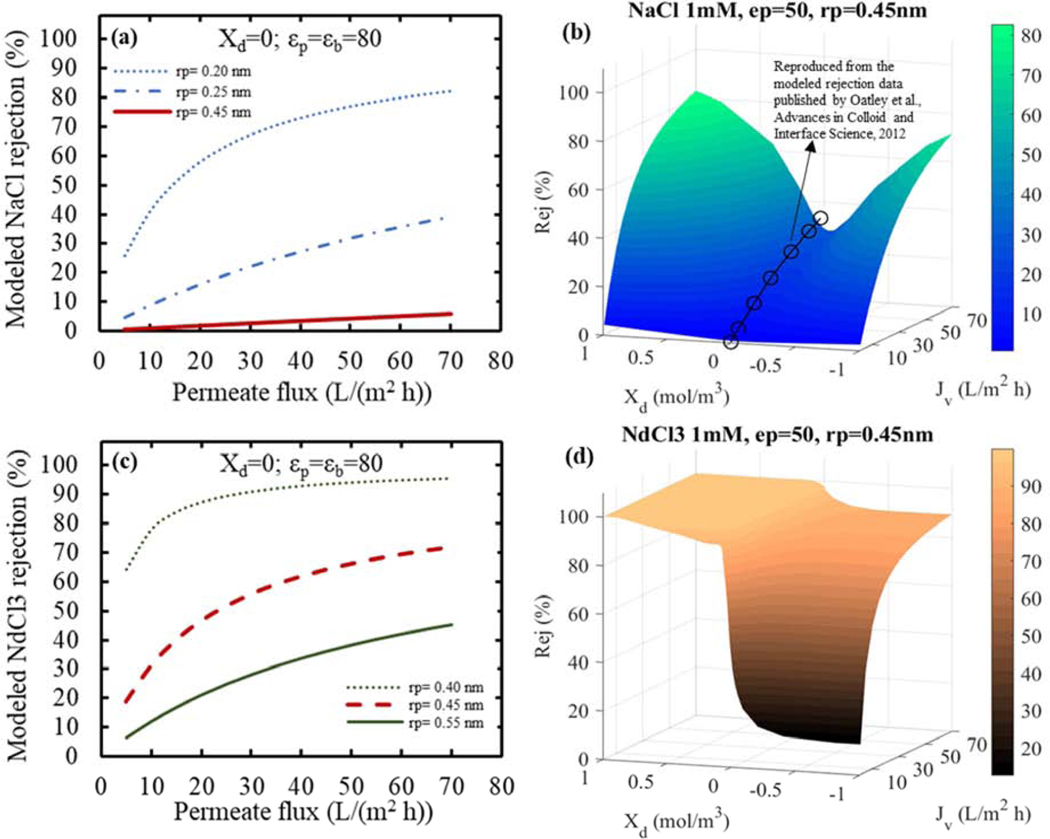

5.1. Sodium and neodymium chloride modeled behavior

Donnan steric pore model with dielectric exclusion (DSPM-DE) [1] was used (as presented in detail in section 4 of the SI) for evaluating the overall partitioning into the polymeric matrix (Equation 4) [25] and the subsequent transport through the NF layer (Equation 5) [62] of both sodium and neodymium with a common counterion (chloride). The first term in Equation 4 (φi) is the steric exclusion, the first exponential term is associated to the dielectric exclusion using the Born solvation energy model, and the last exponential term is the Donnan exclusion. Main parameters of the ions being studied in regards with the modeling (bulk diffusion coefficient and Stokes radius) are presented in Table 6 and Table SI 4. Typically, there are four unknown parameters in the DSPM-DE, the effective active layer thickness (Δx/Ak), the pore radius (rp), the dielectric constant within the pore (εp) and the volumetric charge density (Xd). For all the present modeled results, effective active layer thickness was correlated by linking solvent velocity with membrane thickness through the Hagen-Poiseuille-type relationship [1,36], by using the water permeabilities experimental results of the membranes, and the other parameters (rp, εp, Xd) are respectively indicated. Initial validation of the model simulation used in this study was performed (section 12 in the SI), by initially comparing against the experimental and modeled rejections from Bowen [1] (Figure SI 15). Moreover, optimized parameters for the commercial DOW-NF270 were compared to literature [30,33,41] (Figure SI 16 b). Finally, the modeled results from Oatley [63] shown in Figure 9 (b) at the isoelectric point are compared against their experimental results (also used by Roy et al. to validate their simulation [33]) and our modeled outcomes (Figure SI 16 a). Results confirmed the validity of the simulation of the DSPM-DE in this study, with a slightly more sensitivity to the optimized parameters εp and Xd.

Table 6.

Properties of the cation species for the transport through the NF membranes

| Cation | Bulk diffusion coefficienta (× 10−9m2/s) | Stokes radiusb (nm) | Hydration radiusc (nm) | Hydration energyd (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Na+ | 1.335 | 0.184 | 0.382 | −365 |

| Ca2+ | 0.791 | 0.310 | 0.412 | −1,505 |

| La3+ | 0.619 | 0.397 | 0.452 | −3,145 |

| Nd3+ | 0.616 | 0.399 | − | −3,280 |

For consistency, all columns were obtained or calculated using same reference or criteria:

Diffusion coefficients at 25°C calculated from limiting molar (equivalent) ionic conductivities [64] (details are presented on section 10 of the Supplementary Information) and

Stokes radius calculated using Stokes-Einstein equation [27].

Hydration radius from [27].

Hydration energy at 25°C obtained from [28].

Figure 9.

Sensitivity of the modeled rejection for monovalent sodium (a and b) and trivalent neodymium (c and d) cations, with same chloride as counterion. The left-hand side (a and c) presents the pore radius alone effects (meaning a DSPM at the isoelectric point), where the red line represents the pore radius of the PIP-PS35 synthesized NF membrane. (b and d) Tridimensional plots of the modeled rejection sensitivity respect to the membrane permeate flux at different surface charge values (Xd). For the model, the activity coefficients were considered equal to the unity, and assuming concentration polarization effects negligible. Circles in (b) are the modeled rejection data published by Oatley et al. (reproduced from Oatley et al., Figure 8 [63]) for a NF99HF membrane at the isoelectric point, 10 mM, εp=42.2, rp=0.43 nm and Xd=0.

| Equation 4 |

| Equation 5 |

First, the sensitivity of the modeled rejection for both a 1mM NaCl and a 1mM NdCl3 solutions was evaluated, assessing the relevance of the pore radius (rp) term alone on the cation exclusion. Size is expected to be a major contribution, since from the Stokes radii (rs) presented in Table 6, lanthanide cations approach to the modeled pore radius of NF membranes, meanwhile sodium cations remain significantly smaller. In order to corroborate size effects alone, the simulation of the membrane rejection was run at its isoelectric point (Xd=0) and simplifying the model to DSPM (with no dielectric exclusion effects). Figure 9 presented how the neodymium chloride (c) rejection was significant for modeled pore radius in the order of NF membranes (~0.4–0.5 nm). Although, the rejection for sodium chloride (Figure 9 (a)) approached to zero by just size exclusion (at the modeled pore radius of 0.45 nm).

In a more realistic condition, the salt rejections by each exclusion term alone do not occur, and combination of the three mechanisms happen simultaneously. This increases even further the sensitivity of each term in the rejection performance of the membrane, where the partitioning equation used in the DSPM-DE (Equation 4) is a nonlinear relation of each exclusion term multiplying each other. Therefore, knowing the role of the modeled pore radius for the rejection of sodium and neodymium ions, a better representation of the system was then analyzed. This better representation consisted in a fixed pore radius size of 0.45 nm (within the range of commercial and lab-made PIP-based polyamide NF membranes [39]), and a fixed dielectric constant within the pore with a value of 50 (close to optimized values obtained in literature [33,34,65]). The charge effect (Xd) was left variable, so the effects of a positively and a negatively charged NF membrane can be observed. In Figure 9 (b and d) it was plotted how the modeled rejection as a function of the permeate flux was affected by the fixed parameters and the variable volumetric charge density, where the Xd values used were in the order of magnitude found by Bowen [1] for the DSPM-DE using ~ 1mM concentration. For the case of sodium chloride (b), it was observed a common depression at neutral surface charge (at its isoelectric point – as contrasted to results obtained by Oatley [63] presented as circles in Figure 9 (b)), where NaCl rejection goes down due to the absence of Donnan exclusion [35]. Moreover, rejection increases for any absolute value of the surface volumetric charge, meaning that either a negative or a positive potential at the NF membrane surface will increase the rejection of this dissolved salt, especially for high permeate fluxes. This results are consistent with the findings in [1]. Differently, neodymium chloride rejection did not present a minimum at the membrane’s isoelectric point. As expected, high rejections were encountered at positive volumetric charge density values. However, the rejection dramatically decreased at negative volumetric charge densities with low permeate fluxes. It is important to note, that even for negative Xd values a high rejection (~85%) of neodymium chloride was obtained, corresponding to the cases of high permeate fluxes. Although, this decrease from positive to negative Xd values at high permeate fluxes can mean valuable losses of the recovered material, or toxicity in a contaminated source. Most importantly, the modeling results revealed the potential of high selective separation of Na+/La3+ using a NF membrane with a positive surface volumetric charge density at low operating pressures (equivalent to low permeate fluxes). The independence of neodymium rejection with the permeate flux (in the case of the positively charged membrane), and the corresponding increase in sodium transport make this an optimum theoretical condition. Moreover, this would provide a flexible operation in which low energy requirements would be needed, and thus the installation of a plant in areas with aqueous sources affected with significant concentrations of lanthanides could be implemented without major limitations. For a complementary view perspective of the 3D plots presented in Figure 9 (b and d), contour graphs were also plotted (Figure SI 17).

5.2. Modeling the performance parameters of the synthesized NF membranes

In order to understand the difference in performances between the negatively and positively charged nanofiltration membranes synthesized in this study, in terms of rejection of sodium and lanthanides chloride solutions, the DSPM-DE was applied again. First, modeled pore radius obtained for each synthesized NF membrane was used (as presented in Table 4), and the effective active layer thickness was correlated by linking solvent velocity with membrane thickness through the Hagen-Poiseuille-type relationship [1,36] ((Δx/Ak) =0.99 μm). Then, experimental results from single NaCl rejection were fitted with the model and both optimized εp and Xd were obtained (as presented in Table 7), and thus constructing a relative comparison of sodium to lanthanides rejection mechanism. Analyzing the results, consistent with the zeta potential values, negatively and positively charged volumetric charge densities were obtained for PIP-PS35 and PIP/PAH-PS35, respectively (Table 7). These parameters can be compared to the tested commercial NF270 with values reported in literature [33] (Table SI 3). The modeled pore sizes previously described for the synthesized NF membranes match the one from the NF270 (with a value of 0.43 nm). Also, the dielectric constant within the pore falls in between the values obtained from the PIP-PS35 and PIP/PAH-PS35 membranes, with a value of 42.2. Finally, the volumetric charge density of the NF270 presents a higher negative value compared to the negatively charged PIP-PS35 membrane. These differences between both negatively charged membranes (lower dielectric constant and charge density for the case of PIP-PS35) would be the main characteristics that differentiate the performance between both membranes.

Table 7.

Optimized parameters used in the DSPM-DE for NaCl, LaCl3 and NdCl3 shown in Figure 10

| Parameter | PIP-PS35 | PIP/PAH-PS35 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| εp (−) | 50 | 40 |

| Xd (mol/m3) | −0.023 | 0.19 |

Moreover, comparison between experimental and modeled rejection of the synthesized NF membranes for NaCl are presented in Figure 10, showing a good agreement. Variations in the dielectric constant within the pore have been commonly related to the pore size and its corresponding geometric restriction for the solvation of ions by the limited number water molecules within the intermolecular free volume (modeled as pores for NF membranes) [1]. For the case of this study this simplified perspective would not be able to explain the variation on the obtained dielectric constants, since modeled pore sizes were very similar (Table 4). Dielectric constants are much more complex and hardly measurable in non-bulk conditions. The dielectric constant of a solvent (water in this case) is a property related to the polarization of the water molecules (both electrons distribution within the atoms and atomic configuration within the molecules, as well as alignment of already existing permanent molecular dipoles), and it is not just affected by the solvent properties but also by the environmental potentials, as for example the ions and their properties or concentrations [66]. Under this concept, the increase in the number of charged groups in the NF layer (addition of amine groups and potential increase in carboxylic acids from unreacted TMC due to the reduction on the degree of polymerization for the larger molecular size of the PAH), would explain the reduction on the value of the dielectric constant within the pore, relative to the PIP-PS35 membrane.

Figure 10.

Comparison between model and experimental results for NaCl, LaCl3 and NdCl3 rejections (solid lines) for synthesized (a) PIP-PS35 and (b) PAH-PS35 membranes. Experimental results (symbols) are presented again for contrasting against modeled results. Water permeability of mbranes ~9 (L/m2 h bar). Model parameters: (a) εp=50, rp=0.45 nm, Xd=−0.023 mol/m3, and (b) εp=40, rp=0.44 nm, Xd=0.19 mol/m3

For the case of LaCl3 and NdCl3 rejections, they were modeled using the optimized parameters from NaCl, and results are presented in Figure 10. For the case of the PIP/PAH-PS35 membrane, a good agreement was observed, which can be expected since optimized dielectric exclusion was high, in addition to a positively charged membrane, it ensured a high modeled rejection of lanthanum and neodymium chloride (close to the experimental results). However, for the case of the synthesized PIP-PS35, where high experimental Na+/Ln3+ selectivity was found, and the surface potential is negative, the DSPM-DE did not to predict the high LnCl3 rejections.

Two potential reasons for the higher experimental rejections of lanthanides chloride relative to the model prediction, in the case of higher Na+/Ln3+ selective separation and a negatively charged surface (PIP-PS35) can be related to: the charge density and solute size. First, ionic exchange of lanthanide cations and carboxylic acids groups from the nanofiltration layer can interfere with the net volumetric charge density. Affecting the surface potential, specially towards a positive surface potential may lead to an increase in the rejection of multivalent cations. The strong absorption of lanthanides was analyzed and is presented in the following section. Secondly, screening effects and particularly the impact of hydration radius may lead to higher experimental results. In the DSPM-DE the Stokes radius was used because of its simplicity of calculation and consistency throughout the model as by Bowen [1]. However, loss of the water layers solvating the ions is not expected to occur completely and the effects of hydration offering a bigger physical size of the ions may be more realistic [29]. Moreover, from the results obtained at high ionic strength mixtures, as well as from the pH effects (Figure SI 14), unless no other stronger interaction existed, shielding of the surface charge became more efficient, which is explained by a reduction of the Debye length [67]. This means, that reduction of the Donnan exclusion term occurred and a high rejection of lanthanides became more plausible to be a cause of screening (size) effects. Hydration radius of the studied cations are presented in Table 6, along with the hydration energy. Neodymium and lanthanum present 10 folds greater energy of hydration relative to sodium, meaning the hydration radii of both lanthanides are expected to be more energetically stable.

5.2.1. Sorption of La3+ by carboxylic acid groups

The adsorption of La3+ on the membrane was analyzed and discussed in detail in section 14 of the SI. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used for identifying the binding energy of La-O on a negatively charged membrane (PIP-PS35) after passing a solution with lanthanum chloride (and rinsed afterwards), and compare quantitatively against the same membrane with no solution passed through (pristine). Oxygen and lanthanum binding energy peaks are presented in Figure SI 18. The membrane exposed to the LaCl3 solution presented a broader and single oxygen binding peak, and lanthanum binding energies peaks were also clear, verifying the presence of adsorbed lanthanum. Quantitatively information from the XPS analysis (presented in Table SI 5) gave a 2.5:1 ratio of O:La, which denoted a strong affinity. Moreover, this ratio means that lanthanum cations were not fully coordinating their +3 valence to oxygens, thus some of the positive charges remained with it, giving the chance of even inverting the surface potential of the NF membrane.

6. Conclusion

The synthesis of a nanofiltration membrane with additional weak basic functional groups using commercially available polyallylamine hydrochloride (PAH) and trimesoyl chloride by rapid interfacial polymerization was accomplished. Also, it was demonstrated the real increase in surface zeta potential of the synthesized positively charged (PIP/PAH-PS35) versus the negatively charged membrane, proving the addition of the unreacted primary amines on this hybrid NF layer with enhance positive charges. An additional UF porous support (PES) was used for the synthesis of both NF membranes, bringing reproducible results of the hydrophilic and surface charge properties. Modeled nanofiltration pore radius calculated through the uncharged solute rejection approach provided no major difference between both NF membranes. A more irregular surface for the case of the PIP/PAH-PS35 membrane was found from the analysis of the SEM and the AFM results, meanwhile its counterpart showed a regular globular pattern throughout its surface. In terms of performance, both synthesized membranes presented similar water permeability coefficients and were able to reject lanthanides in high rates. Particularly, for the case of PIP/PAH-PS35 a superior stability on the rejection of lanthanides was found, with minor drops under high ionic strengths, low pH solutions, low permeate flux, and water recovery conditions. Stable high rejections were also true in a lesser degree for divalent calcium cations, although significant drops in sodium rejections were obtained. Enhancement of the Na+/La3+ selectivity was only detected for the case of low permeate fluxes, including at the 85% water recovery permeate sample. At those operating conditions, the separation by charge prevailed over the transport of ions dependent on the convective coupling effects. Furthermore, the differences on the transport mechanisms between lanthanides and sodium chloride were elucidated using the DSPM-DE. Potential high selectivity can be obtained with truly positively charged NF membranes operating at low permeate fluxes, where neodymium rejections showed to be unaltered, but sodium is largely reduced The high rejections of lanthanides cations were well explained by the screening effects from the modeled pore size of NF membranes approaching the Stokes radii of these cations, coupled with dielectric exclusion and a positive volumetric charge density on the membrane. However, for negatively charged NF membranes a high rejection was not predicted, particularly at low permeate fluxes, contradicting to the experimental results. A strong adsorption affinity of La3+ on the surface of the negatively charged NF membrane was found through XPS analysis, potentially altering the surface charge.

Supplementary Material

NF membranes containing additional weakly basic functional groups were synthesized

Addition of polyallylamine modified both surface properties and performance

Selective separation of lanthanides using NF membranes was quantified

Donnan steric pore model with dielectric exclusion elucidated transport mechanism

Acknowledgement

This research was financially supported by Honeywell Corporation, NSF KY EPSCoR grant (Grant no: 1355438), and NIH-NIEHS-SRC (Award number: P42ES007380). Also, we appreciate Solecta membranes for providing the porous ultrafiltration PS35 membranes. Moreover, appreciating the collaboration of the entire lab team, which brings valuable background and knowledge for making this study a success. Finally, we thank Nicolas Briot from the Electron Microscopy Center at the University of Kentucky for assistance in the SEM imaging process, and Phillip Sandman (undergraduate student) for experimental help

Nomenclature

- A

Water permeability coefficient (L m−2 h−1 bar−1)

- ci

Concentration of ion i (mol/m3)

- Di,p

Hindered diffusion coefficient (m2/s)

- F

Faraday constant (C/mol)

- ji

Flux of ion i (mol m−2 s−1)

- Jv

Permeate volume flux (m/s)

- k

Boltzmann constant (J/K)

- Ki,c

Hindrance convective factor (−)

- P

Pressure (bar)

- rp

Modeled pore radius of NF layer (10−9 m)

- rs

Stokes radius (10−9 m)

- R

Universal gas constant (J mol−1 K−1)

- T

Temperature (K)

- Xd

Volumetric charge density (mol/m3)

- zi

Valence of ion i (−)

- γi

Activity coefficient of the ion i (−)

- Δx/Ak

Effective active layer thickness (10−9 m)

- ΔW

Born solvation energy barrier (J)

- ΔψD

Donnan potential (V)

- εp

Dielectric constant of the water within the NF membrane “pores” (−)

- εr

Dielectric constant of water (−)

- Φi

Steric exclusion term (−)

- ψ

Electrical potential (V)

Footnotes

Francisco Léniz-Pizarro: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization. Chunqing Liu: Writing – Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. Andrew Colburn: Writing – Review & Editing. Isabel C. Escobar: Writing – Review & Editing. Dibakar Bhattacharyya: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Appendix. Supplementary Information

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Bowen WR, Welfoot JS, Modelling the performance of membrane nanofiltration-critical assessment and model development, Chem. Eng. Sci. 57 (2002) 1121–1137. 10.1016/S0009-2509(01)00413-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bandini S, Vezzani D, Nanofiltration modeling: The role of dielectric exclusion in membrane characterization, Chem. Eng. Sci. 58 (2003) 3303–3326. 10.1016/S0009-2509(03)00212-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Werber JR, Osuji CO, Elimelech M, Materials for next-generation desalination and water purification membranes, Nat. Rev. Mater. 1 (2016). 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bidhendi GN, Nasrabadi T, Use of nanofiltration for concentration and demineralization in the dairy industry, Pakistan J. Biol. Sci. 9 (2006) 991–994. 10.3923/pjbs.2006.991.994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]