Abstract

Extracellular matrix (ECM) products have the potential to improve cellular attachment and promote tissue-specific development by mimicking the native cellular niche. In this study, the therapeutic efficacy of an ECM substratum produced by bone marrow stem cells (BM-MSCs) to promote bone regeneration in vitro and in vivo were evaluated. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis and phenotypic expression were employed to characterize the in vitro BM-MSC response to bone marrow specific ECM (BM-ECM). BM-ECM encouraged cell proliferation and stemness maintenance. The efficacy of BM-ECM as an adjuvant in promoting bone regeneration was evaluated in an orthotopic, segmental critical-sized bone defect in the rat femur over 8 weeks. The groups evaluated were either untreated (negative control); packed with calcium phosphate granules or granules+BM-ECM free protein and stabilized by collagenous membrane. Bone regeneration in vivo was analyzed using microcomputed tomography and histology. in vivo results demonstrated improvements in mineralization, osteogenesis, and tissue infiltration (114 ± 15% increase) in the BM-ECM complex group from 4 to 8 weeks compared to mineral granules only (45 ± 21% increase). Histological observations suggested direct apposition of early bone after 4 weeks and mineral consolidation after 8 weeks implantation for the group supplemented with BM-ECM. Significant osteoid formation and greater functional bone formation (polar moment of inertia was 71 ± 0.2 mm4 with BM-ECM supplementation compared to 48 ± 0.2 mm4 in untreated defects) validated in vivo indicated support of osteoconductivity and increased defect site cellularity. In conclusion, these results suggest that BM-ECM free protein is potentially a therapeutic supplement for stemness maintenance and sustaining osteogenesis.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The attachment, spreading, retention, and successful differentiation of local responsive cells on implanted graft materials are critical for new bone formation.1,2 In bone tissue engineering, scaffold-only approaches have been used with reasonable success for bone repair in small defect sites3,4 and are available in different forms, such as granules,5–7 strips,8,9 or putty.10 However, the success of using scaffolds alone11 and/or scaffolds modified with growth factors12,13 for bone regeneration in critical-sized defects remains limited. In an effort to solve this problem, stem cells, such as mesenchymal cells have been paired with different types of scaffolds to accelerate bone regeneration in critical-sized defects.12,14

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) hold great promise for bone regeneration15 because of their inherent ability to differentiate to a bone-specific lineage and restore normal tissue function during homeostasis. However, a critical barrier to realizing the full potential of stem cell therapies lies in the transition from their normal stem cell niche to the site of injury or disease.16,17 It is now widely acknowledged that behavior of stem cells is governed, to a large extent, by cues from the extracellular matrix or stem cell niche.18–20 When MSCs from the bone marrow are exposed to artificial substrates in vitro, their gene expression changes and they frequently undergo spontaneous differentiation or enter replicative senescence.21 Studies have demonstrated a potential for the differentiation of MSCs into osteogenic lineage in vitro,22–25 with mixed in vivo results in terms of efficacy.23 It is plausible that bone substitute materials fail to adequately recapitulate the MSC niche in vivo, resulting in less than optimal function of regenerative cells present at the site.

Bone substitutes or other graft materials are rarely discussed in terms of their ability to replicate or reconstitute the complex nature of the native microenvironment so as to restore normal function at the cellular level to promote regeneration. In order to elicit cell functions that are desirable to promote regeneration, it is necessary to make improvements to bone substitute materials in order to recreate key properties of the stem cell niche and promote normal stem cell function. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BM-MSC) therapies are a common therapeutic for nonunion fractures since they have been shown to promote tissue repair and regeneration due to their ability to modulate the immune-microenvironment,26 stimulate angiogenesis,27 and give rise to multiple bone specific cell types. However, one of the obstacles associated with MSC therapies is obtaining relevant numbers of MSCs for clinical treatment. To improve the functionality of recruited BM-MSCs in an orthotopic wound-healing environment in vivo, a cell culture-derived extracellular matrix (ECM) substratum produced by bone marrow stem cells (BM-ECM) was generated using bone marrow stromal cells.28

In this study, we expand our preliminary work29 that demonstrated in vitro cell culture maintenance and phenotypic expression on the BM-ECM. This current study focused on determining the feasibility of applying BM-ECM therapeutically to promote bone regeneration in vitro and to recreate the stem cell niche and promote osteogenesis in vivo. It hypothesized that the use of BM-ECM would promote greater recruitment of osteoprogenitor cells, higher degree of stemness maintenance, and an increase in overall bone regeneration at the defect site. This hypothesis was evaluated by measuring BM-MSC proliferation and differentiation in vitro followed by analyzing the impact of BM-ECM free protein with different commercial bone graft restoratives, including an acellular collagen wrap and calcium phosphate granules, on bone volume regeneration and regenerated bone quality in a critical-sized rat femoral defect model.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. BM-ECM-free protein preparation and characterization

BM-ECM plates, provided by StemBioSys,19 onto which BM-MSCs had deposited an ECM, were first rehydrated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 hr at 37°C. BM-ECM protein matrix was then harvested from the bottom of the dish by mechanically scrubbing the ECM in the plates using a sterile, putty spatula. The PBS containing free proteins was homogenized on ice and the protein concentration measured using the Bradford Assay. Compositional analysis of BM-ECM was evaluated by mass spectrometry as previously reported,30 using high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry.

2.2 |. BM-MSCs cell culture

BM-MSCs (PCS-500-012™) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured in minimum essential medium alpha (MEM-α) medium containing 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), passaged at 80% confluency, with all cells used being passage 4 or lower. Cells were detached using 0.1% trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. The cells were then subcultured at 6000 cells/cm2 using MEM-α medium without free protein in tissue cultured plates (negative control) and with the indicated concentrations of BM-ECM free-protein (treatment groups). Media was changed every 3 days and the study continued for 14 days. All reagents for cell studies were purchased from ThermoFisher (Waltham, MA) unless otherwise specified. For each experiment, at least four independent experimental replicates were measured.

2.3 |. Flow cytometry and MSCs cell sorting

BM-MSC phenotype was confirmed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis prior to the in vitro study.20 To identify the immunophenotypic profile, expression of stage-specific embryonic antigen-4 (SSEA-4), a stem cell marker, was analyzed before and after the in vitro study. Cell suspensions were incubated with SSEA-4 primary mouse antibody while nonspecific isotype IgG was used as a negative control. The labeled cell suspension was then washed with 5% FBS and 0.01% sodium azide in PBS. The cell suspension was then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody, followed by washing and then immediately analyzed using the Becton Dickinson FAC Starplus flow cytometer to determine the percentage of stained cells, with at least 10,000 instances measured per sample.

2.4 |. Animal model and surgical procedure

A rat femoral model was used in this research since this model was reported to be capable of supporting weight-bearing femoral defects31 and have been used frequently in orthopedic tissue engineering studies.32 This model has been reported for easy handling33 and given the bone matrix remodeling rate in rats, the studies were relatively shorter compared to large animal models while providing highly valuable data in terms of therapeutic safety and feasibility during 2 months of the study.33,34 This study was approved by the IACUC at the University of Texas at San Antonio to create a critical-sized femoral segmental defect (6 mm) in the mid diaphysis of the right femur of skeletally mature Sprague Dawley rats.34,35 The rats, weighing 35–400 g (10–14 weeks’ old), were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Houston, TX). Briefly, the rats were anesthetized with 3–5% isoflurane and prepped for surgery. The anterolateral aspect of the femoral shaft was exposed through a 3 cm incision, and the periosteum and attached muscle were stripped from the bone.

The rectangular Cytoplast® collagen wrap was saturated with normal saline and placed around the femur on the mid-diaphysis.36 The wrap was trimmed to a size that overlapped 2–4 mm on either side of the defect area and completely enclosed the bone when sutured. The wrap was kept open while a polydactyl plate (27 × 4 × 4 mm3) was placed on the anterolateral surface of the femur on top of the wrap. The plates were predrilled to accept 0.9-mm diameter threaded Kirschner wires.32 The bases of these plates were formed to fit the contour of the femoral shaft. Pilot holes were drilled through both cortices of the femur using the plate as a template and threaded Kirschner wires were inserted through the plate and femur. The notches that were 6 mm apart on the plate served as a guide for bone removal. A small Microaire oscillating saw (Charlottesville, VA) created the defect while cooling the tissue with continuous irrigation in an effort to prevent thermal damage. The defect was then left (a) empty or untreated (negative control group), (b) packed with calcium phosphate granules (Mastergraft® Granules, Medtronic™, Minneapolis, MN) or (c) packed with calcium phosphate granules+BM-ECM BM-ECM free proteins. Mastergraft® Granules37 have been previously reported to possess 80% interconnected porosity and were composed of 15% slow resorbing hydroxyapatite (HA) and 85% fast resorbing beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP). This composition ratio was chosen for this study due to its reported long-term stability and resorption rate.38

The collagen wrap was then secured in place with a polyglactin 910 or Vicryl equivalent suture (tied around the femur and scaffold) with measures to ensure that no vessels or muscles were included. A total of two sutures, one on the proximal side and one on the distal side, were used. The soft tissue was approximated if necessary with absorbable suture approximately 4–0 or 5–0 and skin clips and/or monofilament, nonabsorbable suture approximately 4–0 or 5–0. Animals were allowed full activity in their cages postoperatively and survived for up to 8 weeks. Using a Carestream system, radiographic evaluation of bone healing was performed on the animals at bi-weekly intervals. At the completion of the study time points (4 or 8 weeks), animals were euthanized by 3–5% isoflurane and excised femurs were stored in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Table 1 lists the groups and number of animals used in this study.

TABLE 1.

Animal experiment design

| Group | Number of animals |

|---|---|

| Empty defect (negative control) | 20 rats (10 for 4 weeks, 10 for 8 weeks) |

| Calcium phosphate granules +collagen wrap | 20 rats (10 for 4 weeks, 10 for 8 weeks) |

| Calcium phosphate granules+BM- ECM+collagen wrap | 20 rats (10 for 4 weeks, 10 for 8 weeks) |

Abbreviation: BM-ECM, bone marrow specific extra cellular matrix.

2.5 |. Ex vivo μCT imaging and histology analysis

Following harvesting, the femurs were scanned using microcomputed tomography (μCT) SkyScan1076 (Bruker, Kontich Belgium) scanner at 100 kV source voltage and 100 mA source current, with an 0.05 mm aluminum filter and a spatial resolution of 8.77 μm. Reconstruction and analysis were performed using Bruker’s NRecon and CTAn, respectively. Bone volume, bone mineral density, and polar moment of inertia (PMI) were calculated over the region of interest that was defined as a 6 mm tall region bridging the defect site.35 All data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test for post-hoc analysis of significance. PMI was measured from μCT analysis as a representative metric for structural stability. In addition, bone mineral density (BMD), bone increase percentage data were obtained from imaging results. After μCT analysis, tissue specimens were fixed in formalin solution, followed by dehydration in ethanol. Dehydrated samples were embedded in Technovit® 7200 VLC and sliced to 50–100 μm thickness. Samples were then stained for calcium, connective tissue, and collagen type I using Paragon and Analine Blue. Digital photomicrographs were taken using a Lioheart Biotek (Winooski, VT).

2.6 |. Statistical Testing

Quantitative data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA for the in vitro studies (across free protein concentration) or a two-way ANOVA for the in vivo studies (across treatment type and time), followed by Tukey’s test for post-hoc determination of significant differences at p < 0.05. The statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot (v12, Systat Software Inc, San Jose, CA). All data were reported as the average ± SEM.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. BM-ECM free protein characterization

BM-ECM free protein, as shown in Table 2, indicated the presence of collagen apha-3(VI), fibronectin, collagen alpha-1(VI), collagen alpha-1 (I), collagen alpha-2(I), tenascin, collagen alpha-2(VI), emilin, collagen alpha-1(XII), and transforming growth factor beta induced protein (TGFBI). Collagen groups were the largest portion of BM-ECM and Collagen alpha-3(VI) had the highest individual concentration (88 ± 12 counts).

TABLE 2.

Mass spectrometry analysis of mesenchymal stromal cell derived BM-ECM

| Protein name | Unique peptides | Physiological relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen alpha-3(VI) | 88 ± 12 | Modulates osteoblast interactions during osteogenesis [49] |

| Fibronectin | 56 ± 11 | Essential in the early stages of osteoblast differentiation [50] |

| Collagen alpha-1(VI) | 21 ± 3 | Bone matrix structural constituent [51] |

| Collagen alpha-1(I) | 24 ± 4 | Bone matrix structural constituent [52] |

| Collagen alpha-2(I) | 25 ± 3 | Mutations in this gene are associated with osteogenesis imperfecta [53] |

| Tenascin | 21 ± 5 | Influences osteoblast adhesion and differentiation [39] |

| Collagen alpha-2(VI) | 16 ± 1 | Forms a complexes mediating osteoblast interaction during osteogenesis [49] |

| Emilin | 15 ± 4 | Expression at sites of mesenchymal condensations during cartilage and bone formation [41] |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) | 17 ± 3 | Polarity regulation and differentiation of osteoblasts [54] |

| Transforming Growth Factor Beta Induced Protein (TGFBI) | 10 ± 2 | Supports adhesion of osteoblasts [55] |

Abbreviation: BM-ECM, bone marrow specific extra cellular matrix.

3.2 |. In-vitro analysis

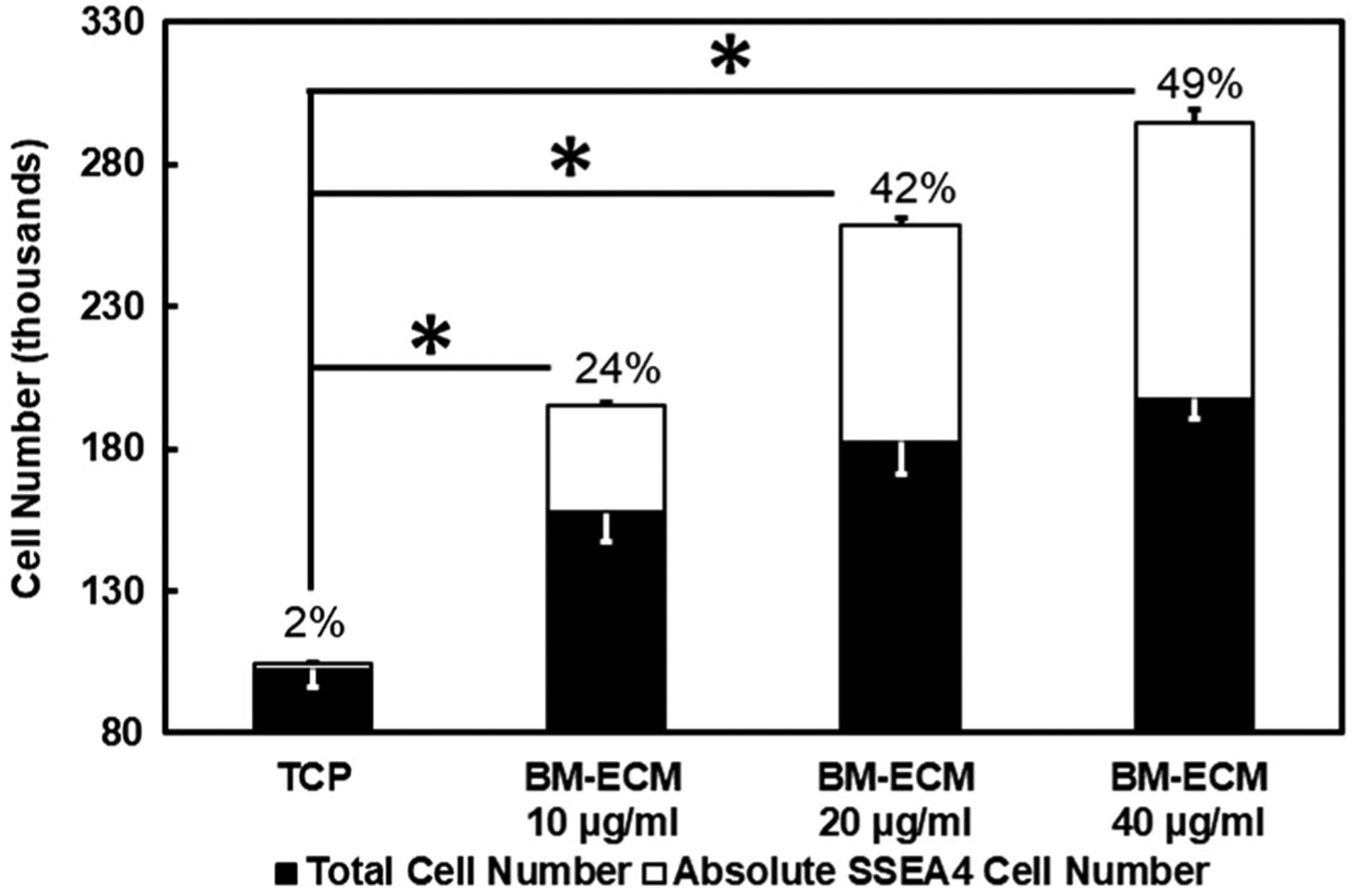

The total number of BM-MSCs cells and the absolute SSEA-4 cell number are shown in Figure 1. The negative control group was observed to have the lowest total number of cells, with only 2% of absolute SSEA-4 in total cell count. The total cell number and absolute SSEA-4 cell number increased significantly by adding BM-ECM (10, 20, and 40 μg/ml) to the culture. It was also observed that the BM-ECM increased the total cell number and SSEA-4 by 51 and 47 times, respectively, compared to the tissue culture plastic control group. The increase in BM-ECM concentration was observed to have a direct impact on the total cell number and SSEA-4 cell count.

FIGURE 1.

The total cell versus absolute SSEA-4 number after 14 days of cell culture on tissue culture plastic (TCP) and different BM-ECM concentrations (10, 20, 40 μg/mL). The percentage indicates the ratio of SSEA-4 (%) in total cell number. SSEA-4 cell growth was used as a marker of cells’ stemness. Results show a significantly different (*p < 0.05) cell growth of SSEA-4 and total cell number between TCP and other groups. BM-ECM, bone marrow specific extra cellular matrix; SSEA-4, stage-specific embryonic antigen-4

3.3 |. Radiography and μCT analysis

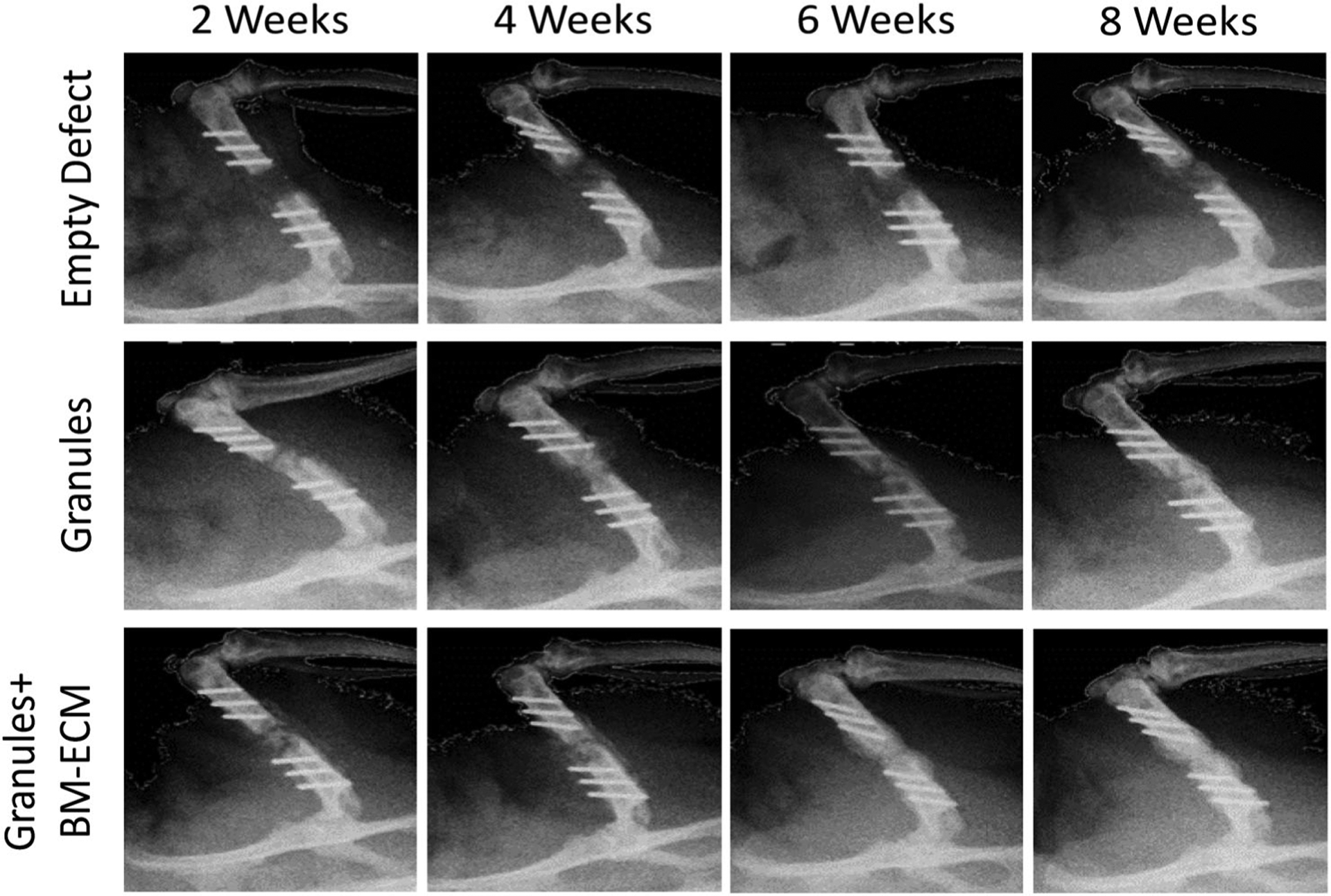

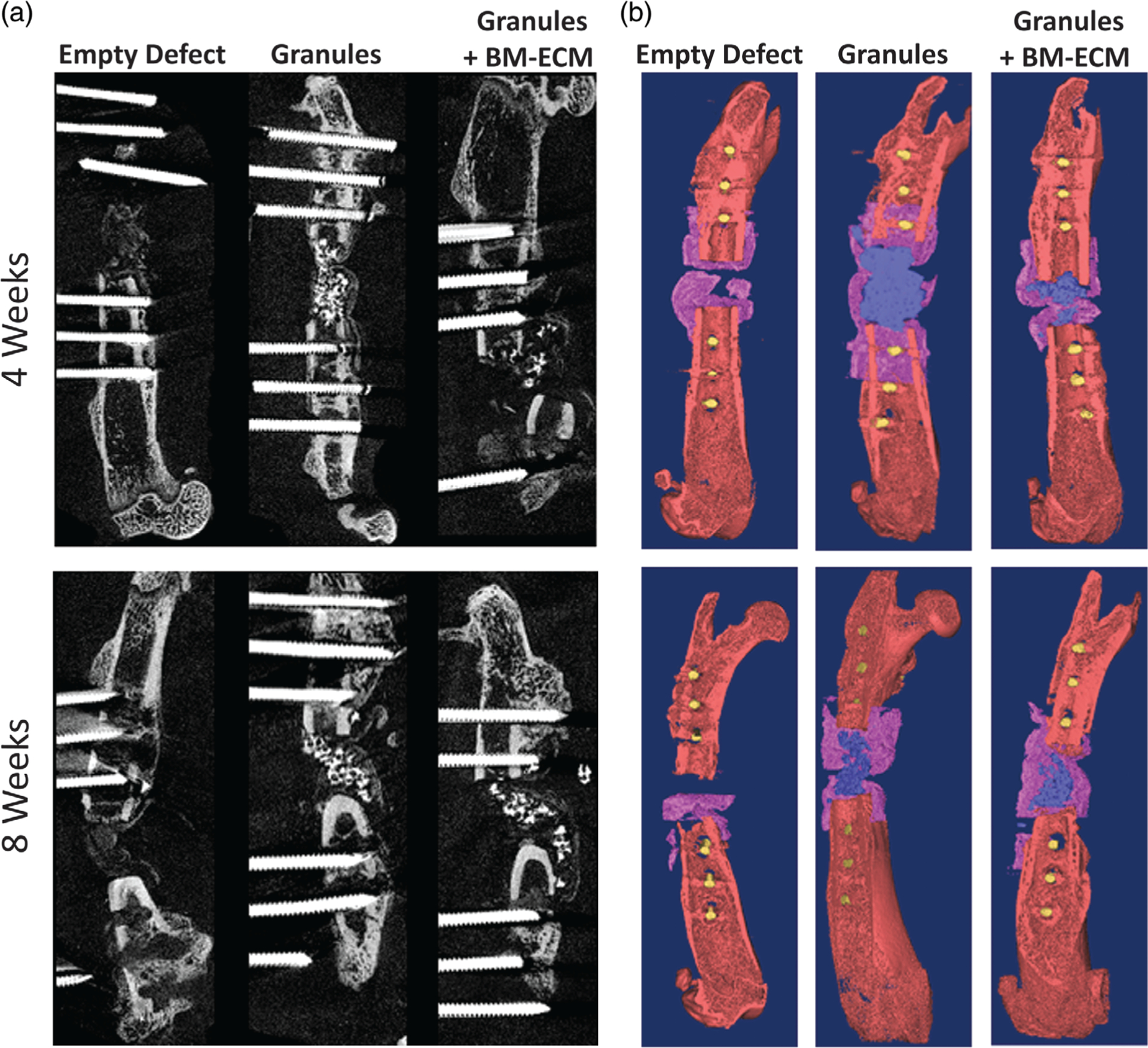

As indicated by increased radio-opacity over time (Figure 2), radiographic examinations over 8 weeks showed all samples maintaining bone stability, continue to healing, and had increased mineralization in both experimental groups with granules compared to the negative control. This corresponded to the observations in our animal study whereby the rats appear to increase weight-bearing on the surgical limbs over time and no animals demonstrating significant pain on regular follow-up evaluations using predetermined metrics. Representative longitudinal-sectional from μCT imaging and 3D reconstruction of the femur defect site after 4 and 8 weeks implantation (Figure 3a) showed bone regeneration with granules and granules +BM-ECM treatments. Pink pseudo-color in Figure 3b indicates the presence of the collagen wrap in all groups.

FIGURE 2.

Radiographic observation on control, granules, and granules+ BM-ECM groups after 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. Images were captured with a scanner at 100 kV source voltage and 100 mA source current with a 0.05 mm aluminum filter and a spatial resolution of 8.77 μm. Healing process is noted during 8 weeks according to the callus tissue reflections in images. Collagen wrap was secured during 8 weeks and the presence of granules was observed in between the defect site in groups with granules and granules with BM-ECM. BM-ECM, bone marrow specific extra cellular matrix

FIGURE 3.

Cross section areas from the μCT images (a) for empty defect, with granules, and granules with BM-ECM groups after 4 and 8 weeks. High contrast areas show the mineralized areas. 3D reconstructions from μCT results (b) from the μCT images for empty defect, with granules, and granules with BM-ECM groups after 4 and 8 weeks. Collagen wraps are pseudo-colored purple, mineralized tissue and granules in the defect site were colored in blue wires are colored yellow. μCT, microcomputed tomography; BM-ECM, bone marrow specific extra cellular Matrix

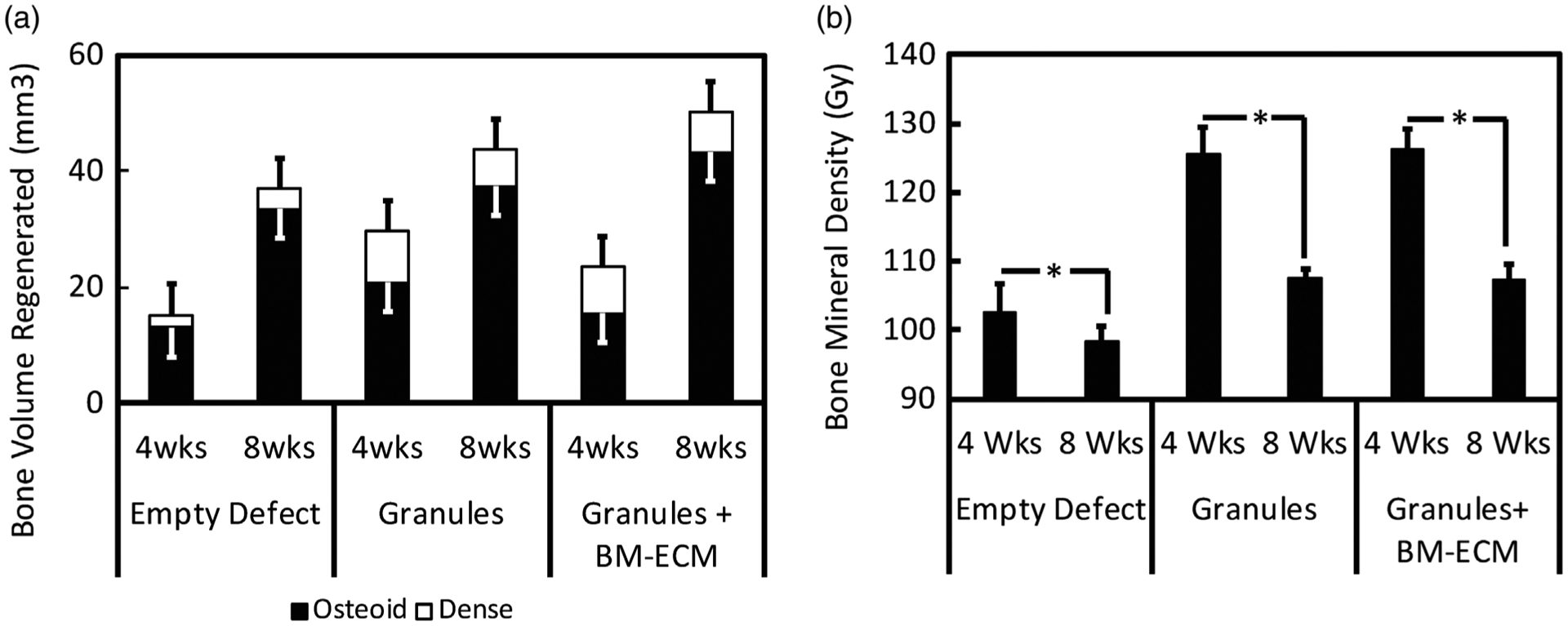

Bone quantity was characterized through bone volume measurement. Osteoid (representing woven and immature mineralized bone) and dense portions (including fully mineralized bone and granules) were measured for all groups after 4 and 8 weeks implantation. Figure 4a shows greater osteoid volume observed in the granules group (20 ± 3 mm3) compared to the control group (13 ± 2 mm3) and the granules+BM-ECM group (15 ± 1 mm3) after 4 weeks implantation. This trend was observed to change at Week 8, with higher osteoid volume observed in the granules+BM-ECM group (43 ± 3 mm3) and in the granules group (37 ± 5 mm3) when compared to the control group (33 ± 1 mm3); however, the regenerated osteoid volume was not significantly different within each group and between groups. Also observed in Figure 4a, the regenerated dense bone volume increased by 6% in the empty defect group after 4 and 8 weeks implantation, whereas the granules and granules+BM-ECM groups demonstrated a subtle decrease in the regenerated dense bone volume by 1.2 and 2.8%, respectively after 4 and 8 weeks implantation. Although not statistically different, a higher total bone volume (regenerated osteoid + regenerated dense bone) was observed for the granule group (30 ± 4 mm3) and the granule+BM-ECM group (23 ± 3 mm3) in the first 4 weeks compared to the empty defect (15 ± 3 mm3), with all groups increasing in total bone volume from 4 to 8 weeks.

FIGURE 4.

Bone quantity and bone quality calculated for empty defects, granules, and granules with BM-ECM after 4 and 8 weeks. (a) Bone quantity is reported as the regenerated bone volume (mm3) by showing osteoid and dense volumes. (b) Bone quality is reported as the bone mineral density (Gy). BMD was significantly different (p < 0.05) from 4 to 8 weeks in all groups. Bone volume regeneration was no significantly different within the groups.BM-ECM, bone marrow specific extra cellular matrix

In order to evaluate the bone quality, bone mineral density (Figure 4b) was calculated for all groups. Bone quality, as defined by bone mineral density increased by more than 20 Gy by 4 weeks in all groups with granules compared to the control group; however, there was no significant difference between granule groups with and BM-ECM. After 8 weeks, there was a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in bone quality for all groups when compared to bone quality after 4 weeks, and this decrease was attributable to granule resorption.

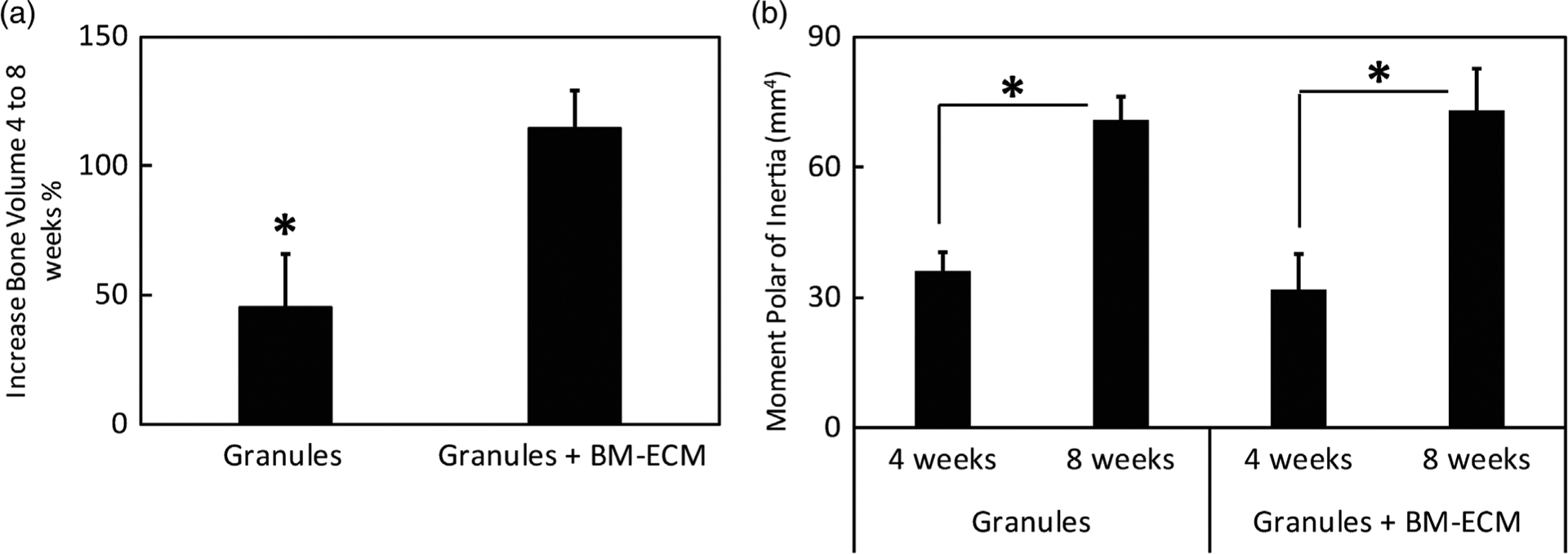

Figure 5a shows the percentage increase in total bone volume (regenerated osteoid + regenerated dense bone) after 4 and 8 weeks implantation for the granules and granules+BM-ECM groups. The granules group was observed to increase by 45 ± 20% in total bone volume, whereas the granules+BM-ECM was observed to increase by 114 ± 15% in total bone volume, suggesting that the percent increase in total bone volume was significantly greater (p < 0.05) for the granules+BM-ECM group.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of BM-ECM on bone increase from 4 to 8 weeks in samples with granules and granules with BM-ECM. (a) Bone increase percentage (%) from 4 to 8 weeks between only granules and granules with BM-ECM. The results show a significant increase in bone percentage between the groups (p < 0.05). (b) Functionality of metrics based on polar moment of inertia (mm4) in granules and granules with BM-ECM groups after 4 and 8 weeks. The results in both groups are significantly different within the groups from week 4 to 8 (p < 0.01). BM-ECM, bone marrow specific extra cellular matrix

PMI known as second polar moment of area was used to describe the inherent rotational stiffness of the bone.39,40 While this parameter was reported to also attribute to the regenerated bone strength41 and the ability of the mineralized tissue in the defect to resist torsion, it was considered as an estimate for the progress of functional healing.39 As shown in Figure 5b, no significant difference in PMI was observed between the granules (36 ± 8 mm4) and granules+BM-ECM group (31 ± 6 mm4) after 4 weeks implantation. Similarly, no significant difference in PMI was observed after 8 weeks implantation for the granules group (71 ± 9 mm4) and granules+BM-ECM group (73 ± 11 mm4). However, significant difference (p < 0.01) in PMI from 4 to 8 weeks implantation was observed within each treatment group.

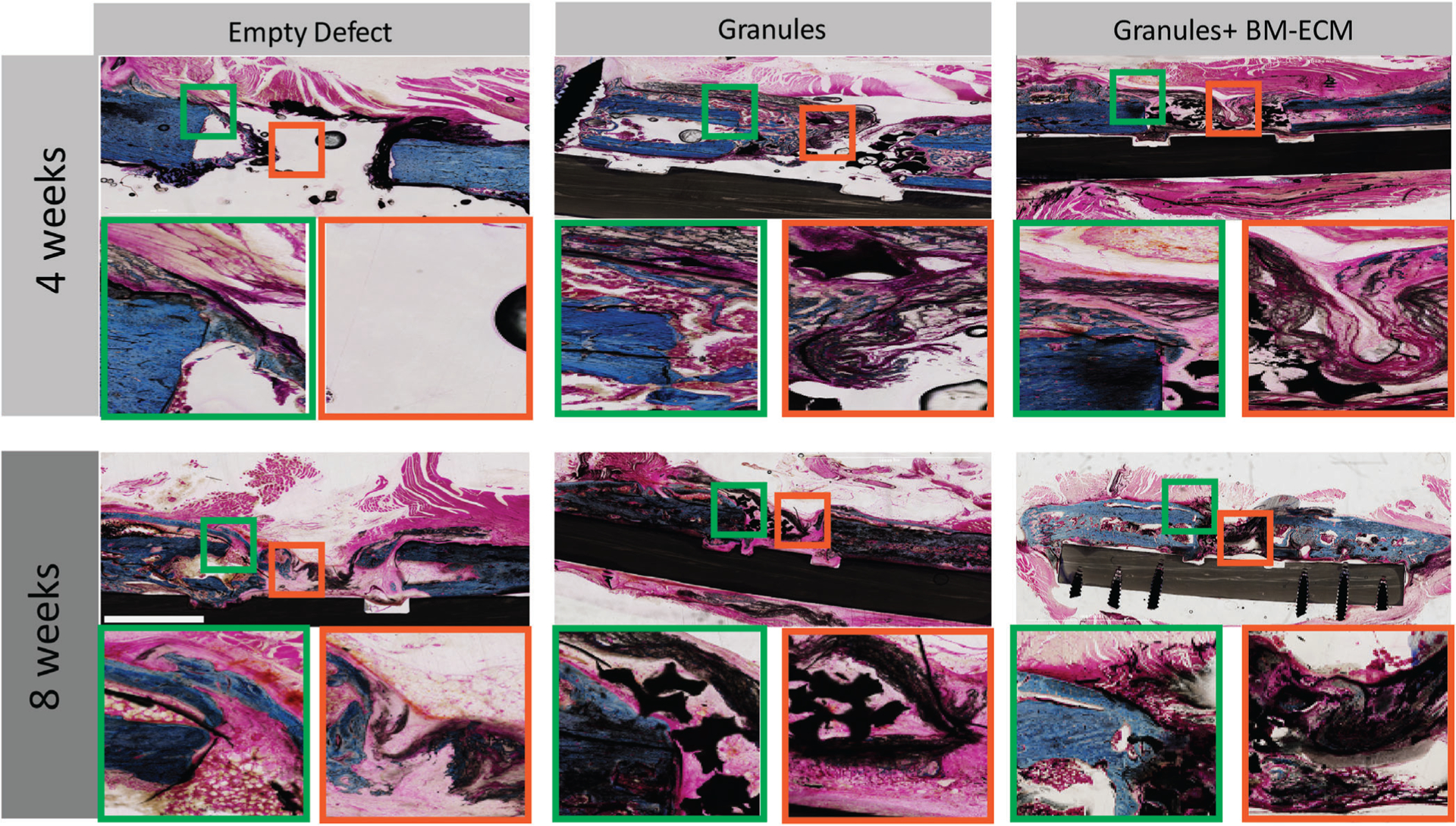

3.4 |. Histological analysis

Histology evaluation of the negative control group with no treatments revealed mineralization of the collagen wrap after 4 and 8 weeks, explaining visible opacity in the radiographs. The defect site showed an increase in mineralization of the collagen wrap after 8 weeks as the mineralized wrap formed a distinct layer from the native cortical bone. In the middle zone, the collagen wrap did not sufficiently act as a barrier or maintain space after both 4 and 8 weeks; however, increased mineralization was seen after 8 weeks. Additionally, the defect site in the untreated group showed fibrous tissue and almost no organized collagen matrix deposition after 4 weeks, although there was a discernable increase in connective tissue at the site after 8 weeks.

While the untreated groups showed no bone formation at the defect site, the samples with granules showed some bony bridging and bone formation in the middle zone of the defect. In addition, the collagen wrap mineralization was thicker after 4 and 8 weeks compared to the group with no treatment. The histology images of the samples with granules showed the retention of the granules at the defect site after both 4 and 8 weeks. Connective tissue formation and initiation of mineralization were observed after 4 weeks. Additionally, there was no mineralized bridging in this group after 8 weeks; however, the connective tissue formation was similar to the untreated group.

Study groups with granules and BM-ECM free protein showed both mineralization and connective tissue formation after 4 weeks. Reduced instability of the site as observed by collagen wrap collapse at the site due to animal load bearing was observed in this group after 4 and 8 weeks, while some instances of collagen wrap instability were observed in the excised samples in both the other groups. Collagen wrap mineralization was observed after 4 weeks with a thicker layer, which was more connected to the cortical bone. The granules were seen in the defect zone, as there was a significant mineralization seen within the granules along with the connective tissue infiltration after 8 weeks.

4 |. DISCUSSION

BM-ECM tissue culture substrates have been previously investigated28,42,43 and found to be an improved cell culture environment to preserve the stem-ness of cultured cells by providing a cell-free extracellular matrix compared to regular tissue culture plates containing one or a select few extracted and purified ECM proteins.44 Comparative studies evaluating cell proliferation rate, cell size, and cell surface markers of MSCs cultured on the BM-ECM matrix versus other commercially available coated dishes exhibited more rapid proliferation, smaller cell size, and higher expression of certain stem cells markers in BM-ECM tissue cultured plates than in the other products.19,28,42,43,45 Having been produced from bone marrow MSCs rather than other standard matrix producing cells (fibroblasts),46,47 BM-ECM tissue culture substrates can be considered to be the more biologically niche-relevant ECM for inducing osteogenesis.

From manufacturer reports, the complex, intact ECM present on the BM-ECM tissue culture plates are laid down by BM-MSCs.19,30,45 The decellularization process, essential in maintaining ECM integrity comprised of gentle removal of the cells using a low concentration, nondenaturing detergent, leaving the biochemistry and architecture of the matrix essentially intact on surface of the dish.19,45 This matrix is comprised of different matrix proteins (as determined by mass spectroscopy, Table 2) and closely resembles tissue ECM.30

In general, most segmental defect bone tissue engineering studies focus on the impact of a single or limited number of growth factor/proteins48–50 on bone regeneration. In addition, synthesized and hybrid51 biomimetic scaffolds with a combination of growth factor release have also been investigated both in vitro and in vivo2 with varying degrees of success. This study investigated the efficacy of using a novel approach to enhance bone healing by incorporating the prototypical bone matrix mimic, namely BM-ECM free protein to improve bone tissue regeneration. It was hypothesized in this study that the BM-ECM free protein would provide a unique protein substratum as well as niche-specific growth factors to promote cell proliferation and ECM secretion and thereby induce osteogenesis in the longer term. Mass spectrometric analysis of the BM-ECM indicated the retention of active components in the matrix after extraction, such as TGF-β1 which was reported to improve cell adhesion and regulate endochondral bone formation.52 In addition, collagenous proteins, the ubiquitous constituents of native bone matrix which present motifs for cell attachment, were observed to be present in BM-ECM. While collagen type I is the primary constituent of the bone ECM, fibronectin has been reported to be essential for continuous collagen integrity in newly produced ECM53 and was also observed at a high mass fraction. Furthermore, tenascin present in the BM-ECM has been reported to play an important role in osteoblast adhesion, differentiation, and proliferation54 with some reports also indicating specific functions in both bone fracture repair and/or improving osteoclast adhesion.55 In addition, Emilin a component identified in BM-ECM has been reported at sites surrounding regions of cartilage and bone formation.56 The retention of critical extracellular matrix components of the bone matrix in the biologic BM-ECM product thus suggest the potential for encouraging cell proliferation and stem cell maintenance that is required at early stages of bone healing. in vitro observations of cells cultured on BM-ECM also suggested the potential to significantly increase cell proliferation and maintain MSC stemness with 25 times greater efficacy when compared to tissue culture plastic control substrates (Figure 1).

Calcium phosphate granules have been used widely as a void fillers in bone defects38,57; however, prolonged osteoclastic resorption processes prevent rapid healing and bone formation.58 It is speculated that native cells, such as MSCs, would migrate into the defect site to generate a bony-union through bridging; however, this has been reported only in small or in mechanically protected defect sites.59 In larger defect sites, granules result in robust regeneration when adjunctive therapies, such as rhBMP-2, are used.60 In addition, using only HA/β-TCP granules results in the bone formation limited to the peripheral pores of the granules while the inner pores were filled with fibrous tissues and marrow components in critical sized defect.61 In the present study, the use of BM-ECM complex along with calcium phosphate granules suggested improved mineralization and tissue infiltration into the granules compared to the control groups. The histological evaluation showed that the BM-ECM free protein not only promoted osteogenesis (Figure 6) but the μCT images also supported improved mineralized tissue formation (Figure 5). In addition, BM-ECM free protein showed the highest bridging while there was no bridging observed in the negative control, suggesting the graft therapy was at least osteoconductive. Bone volume observed from μCT reconstructions (Figure 4a) indicated the impact of BM-ECM on bone formation as the overall mineralized volume was higher in groups with BM-ECM complex compared to the other groups tested. The osteoid fraction in the group with BM-ECM was observed to be higher than the other groups after 8 weeks due to the presence of higher amount of collagen complex in the region, which suggested that these collagen complex potentially assist with greater tissue formation or consolidation past the 8 weeks tested. While bone growth was observed in both experimental groups, there was a significant increase in bone growth from 4 to 8 weeks in the group containing BM-ECM according (Figure 5a), especially to the dense mineralized fraction. Furthermore, radiographic observations showed continued healing over time (Figure 2) without any marked inflammation at either 4 or 8 weeks (Figure 6). This observation also indicated the impact of collagen wrap on keeping granules within the defect site with support from the Kirschner wires and sutures.

FIGURE 6.

Histological evaluation for empty defects, granules, and granules with BM-ECM after 4 and 8 weeks. The longitudinal sections were prepared and stained by Paragon and Analine Blue to label calcium, connective tissue, and collagen type I. The images show the bone regeneration, mineralized collagen wrap, and connective tissue formation in different magnification ×4 and ×10. Empty defect area shows a clear center with minimized calcification around the defect sites. Defect sites with granules and granules with BM-ECM show more calcification and the presence of more connective tissue after 8 weeks. Bridging is noticeable in groups with granules and BM-ECM. The scale bar is equal to 1 cm. BM-ECM, bone marrow specific extra cellular matrix

Although the bone quantity results (Figure 4a) showed the impact of BM-ECM on bone volume regeneration, bone mineral density showed no significant differences when comparing the presence of BM-ECM free protein to the group only with granules. The use of granules in bone defects (with or without the BM-ECM) suggested a significant impact on the mineral density as anticipated, as observed in Figure 4b. In addition, both groups with granules exhibited significantly increased functional bone at 8 weeks than at 4 weeks as measured by the PMI.62 Similar behavior of the functional metrics was observed in both experimental groups (granule and granule+BM-ECM), suggesting the impact of granules but not the additive benefit of the BM-ECM complex in terms of regenerated bone tissue functionality.

Histology results indicated the effect of using collagen wrap in mineralization process in all groups. A thin collagen mineralization layer was observed in the negative control groups which increased after 8 weeks; however, no bridging was observed in the empty zone at either 4 or 8 weeks (Figure 6). A thicker mineralized collagen periphery was observed in samples only with granules after 4 weeks which also showed the connective tissue formation along the mineralized region. In addition, a mix of regenerated bone and connective tissues was observed beneath the collagen wrap at the defect site forming a tissue bridge. In contrast, there was more organized bone formation in the collagen wrap in group with BM-ECM, but no bridging was observed at 4 weeks; however, the collagen wrap supported the further development of regenerated bone close to the cortices after 8 weeks as well as the infiltration of both connective and bone tissue into the granules at the defect site (Figure 6). As a comparison between the experimental groups with granules, the bridging started close to the bone defect only in the groups with granules while the bridging happened within the granules at the defect site. Therefore, the histology suggested that addition of BM-ECM enhances direct apposition of bone early (4 weeks) and encourages mineral consolidation late (8 weeks) (Figure 6).

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

BM-ECM, the extracellular matrix free protein complex harvested from bone marrow derived stromal cells demonstrates efficacy in encouraging cell proliferation and stemness maintenance of MSCs in in vitro culture. Furthermore, significant osteoid formation and greater functional bone formation was validated in an orthotopic load bearing critical sized defect model in vivo, indicating support for osteoconductivity and promoting defect site cellularity. In conclusion, the favorable response from BM-ECM free protein suggested a potential use as a therapeutic adjuvant for stem cell maintenance and promoting sustained osteogenesis.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

R. Z. (previously) and S. G. (still) were/are paid employees of StemBioSys, which donated the BM-ECM product tested in this manuscript. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tang D, Tare RS, Yang L-Y, Williams DF, Ou K-L, Oreffo RO. Bio-fabrication of bone tissue: approaches, challenges and translation for bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2016;83:363–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amini AR, Laurencin CT, Nukavarapu SP. Bone tissue engineering: recent advances and challenges. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2012;40:363–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan H, Fernandes H, Habibovic P, et al. Osteoinductive ceramics as a synthetic alternative to autologous bone grafting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13614–13619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellani C, Zanoni G, Tangl S, Van Griensven M, Redl H. Biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics in small bone defects: potential influence of carrier substances and bone marrow on bone regeneration. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:1367–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turunen T, Peltola J, Yli-Urpo A, Happonen RP. Bioactive glass granules as a bone adjunctive material in maxillary sinus floor augmentation. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15:135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyngstadaas SP, Verket A, Pinholt EM, et al. Titanium granules for augmentation of the maxillary sinus–a multicenter study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2015;17:e594–e600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li P, Zhu H, Huang D. Autogenous DDM versus Bio-Oss granules in GBR for immediate implantation in periodontal postextraction sites: a prospective clinical study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2018;20:923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller CP, Jegede K, Essig D, et al. The efficacies of 2 ceramic bone graft extenders for promoting spinal fusion in a rabbit bone paucity model. Spine. 2012;37:642–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu Z-Y, Cui Y, Tao C-S, et al. Mineralized collagen: rationale, current status, and clinical applications. Materials. 2015;8:4733–4750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schallenberger MA, Rossmeier K, Lovick HM, Meyer TR, Aberman HM, Juda GA. Comparison of the osteogenic potential of OsteoSelect demineralized bone matrix putty to NovaBone calcium-phosphosilicate synthetic putty in a cranial defect model. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:657–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawai T, Suzuki O, Matsui K, Tanuma Y, Takahashi T, Kamakura S. Octacalcium phosphate collagen composite facilitates bone regeneration of large mandibular bone defect in humans. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;11:1641–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Witte T-M, Fratila-Apachitei LE, Zadpoor AA, Peppas NA. Bone tissue engineering via growth factor delivery: from scaffolds to complex matrices. Regen Biomater. 2018;5:197–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansen J, Vehof J, Ruhe P, et al. Growth factor-loaded scaffolds for bone engineering. J Control Release. 2005;101:127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadiyala S, Jaiswal N, Bruder SP. Culture-expanded, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells can regenerate a critical-sized segmental bone defect. Tissue Eng. 1997;3:173–185. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraus KH, Kirker-Head C. Mesenchymal stem cells and bone regeneration. Vet Surg. 2006;35:232–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahla RS. Stem cells applications in regenerative medicine and disease therapeutics. Int J Cell Biol. 2016;2016:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu SP, Wei Z, Wei L. Preconditioning strategy in stem cell transplantation therapy. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4:76–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Y, Li W, Lu Z, et al. Rescuing replication and osteogenesis of aged mesenchymal stem cells by exposure to a young extracellular matrix. FASEB J. 2011;25:1474–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai Y, Sun Y, Skinner CM, et al. Reconstitution of marrow-derived extracellular matrix ex vivo: a robust culture system for expanding large-scale highly functional human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Dev. 2010;19:1095–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rakian R, Block TJ, Johnson SM, et al. Native extracellular matrix pre-serves mesenchymal stem cell “stemness” and differentiation potential under serum-free culture conditions. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE, Caplan AI, Bruder SP. Osteogenic differentiation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 1997;64:295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demir AK, Elçin AE, Elçin YM. Osteogenic differentiation of encapsulated rat mesenchymal stem cells inside a rotating microgravity bioreactor: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Cytotechnology. 2018;70:1375–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammed EE, El-Zawahry M, Farrag ARH, et al. Osteogenic differentiation potential of human bone marrow and amniotic fluid-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7:507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu H, Kawazoe N, Tateishi T, Chen G, Jin X, Chang J. In vitro proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured with hardystonite (Ca2ZnSi 2O7) and β-TCP ceramics. J Biomater Appl. 2010;25:39–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna H, Mir LM, Andre FM. In vitro osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells generates cell layers with distinct properties. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puissant B, Barreau C, Bourin P, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of human adipose tissue-derived adult stem cells: comparison with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:118–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffy GP, Ahsan T, O’Brien T, Barry F, Nerem RM. Bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells promote angiogenic processes in a time-and dose-dependent manner in vitro. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2459–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ragelle H, Naba A, Larson BL, et al. Comprehensive proteomic characterization of stem cell-derived extracellular matrices. Biomaterials. 2017;128:147–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen XD. Extracellular matrix provides an optimal niche for the maintenance and propagation of mesenchymal stem cells. Birth Defects Res A. 2010;90:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marinkovic M, Block TJ, Rakian R, et al. One size does not fit all: developing a cell-specific niche for in vitro study of cell behavior. Matrix Biol. 2016;52:426–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Z, Yang D, Ma X, Zhao H, Nie C, Si Z. Successful repair of a critical-sized bone defect in the rat femur with a newly developed external fixator. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;219:115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X, Kidder LS, Lew WD. Osteogenic protein-1 induced bone formation in an infected segmental defect in the rat femur. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGovern JA, Griffin M, Hutmacher DW. Animal models for bone tissue engineering and modelling disease. Dis Model Mech. 2018;11: dmm033084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S, Bedigrew K, Guda T, et al. Novel osteoinductive photocross-linkable chitosan-lactide-fibrinogen hydrogels enhance bone regeneration in critical size segmental bone defects. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:5021–5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown KV, Li B, Guda T, Perrien DS, Guelcher SA, Wenke JC. Improving bone formation in a rat femur segmental defect by controlling bone morphogenetic protein-2 release. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1735–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guda T, Walker JA, Singleton BM, et al. Guided bone regeneration in long-bone defects with a structural hydroxyapatite graft and collagen membrane. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;19:1879–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim H-J, Park J-B, Lee JK, et al. Transplanted xenogenic bone marrow stem cells survive and generate new bone formation in the postero-lateral lumbar spine of non-immunosuppressed rabbits. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1515–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakimoto M, Ueno T, Hirata A, Iida S, Aghaloo T, Moy PK. Histologic evaluation of human alveolar sockets treated with an artificial bone substitute material. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:490–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds DG, Hock C, Shaikh S, et al. Micro-computed tomography prediction of biomechanical strength in murine structural bone grafts. J Biomech. 2007;40:3178–3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner CH, Burr DB. Basic biomechanical measurements of bone: a tutorial. Bone. 1993;14:595–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reynolds DG, Shaikh S, Papuga MO, et al. μCT-based measurement of cortical bone graft-to-host union. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:899–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baroncelli M, van der Eerden BC, Chatterji S, et al. Human osteoblast-derived extracellular matrix with high homology to bone proteome is osteopromotive. Tissue Eng Part A. 2018;24:1377–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng M, Luo K, Hou T, et al. IGFBP3 deposited in the human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-secreted extracellular matrix promotes bone formation. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:5792–5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kleinman HK, Martin GR. Matrigel: basement membrane matrix with biological activity. Seminars Cancer Biol. Elsevier. 2005;15:378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen XD, Dusevich V, Feng JQ, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Extracellular matrix made by bone marrow cells facilitates expansion of marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells and prevents their differentiation into osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1943–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanwinkle WB, Snuggs MB, Buja LM. Cardiogel: a biosynthetic extracellular matrix for cardiomyocyte culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1996;32:478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooper S, Maxwell A, Kizana E, et al. C2C12 co-culture on a fibroblast substratum enables sustained survival of contractile, highly differentiated myotubes with peripheral nuclei and adult fast myosin expression. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;58:200–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S, Lee S, Kim K. Bone tissue engineering strategies in co-delivery of bone morphogenetic protein-2 and biochemical signaling factors. Chun H Park C Kwon I & Khang G Cutting-Edge Enabling Technologies for Regenerative Medicine. 2018). Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, ;233–244). Singapore: .Springer Nature. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kowalczewski CJ, Saul JM. Biomaterials for the delivery of growth factors and other therapeutic agents in tissue engineering approaches to bone regeneration. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porter JR, Ruckh TT, Popat KC. Bone tissue engineering: a review in bone biomimetics and drug delivery strategies. Biotechnol Prog. 2009;25:1539–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lei B, Guo B, Rambhia KJ, Ma PX. Hybrid polymer biomaterials for bone tissue regeneration. Front Med. 2019;13:189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu H, Wergedal JE, Zhao Y, Mohan S. Targeted disruption of TGFBI in mice reveals its role in regulating bone mass and bone size through periosteal bone formation. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012;91:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bentmann A, Kawelke N, Moss D, et al. Circulating fibronectin affects bone matrix, whereas osteoblast fibronectin modulates osteoblast function. J Bone Metab. 2010;25:706–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morgan JM, Wong A, Yellowley CE, Genetos DC. Regulation of tenascin expression in bone. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:3354–3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alford AI, Hankenson KD. Matricellular proteins: extracellular modulators of bone development, remodeling, and regeneration. Bone. 2006;38:749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leimeister C, Steidl C, Schumacher N, Erhard S, Gessler M. Developmental expression and biochemical characterization of Emu family members. Dev Biol. 2002;249:204–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bongio M, van den Beucken JJ, Leeuwenburgh SC, Jansen JA. Development of bone substitute materials: from ‘biocompatible’to ‘instructive’. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:8747–8759. [Google Scholar]

- 58.LeGeros RZ. Properties of osteoconductive biomaterials: calcium phosphates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;395:81–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dumas JE, Prieto EM, Zienkiewicz KJ, et al. Balancing the rates of new bone formation and polymer degradation enhances healing of weight-bearing allograft/polyurethane composites in rabbit femoral defects. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;20:115–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carlisle P, Guda T, Silliman DT, et al. Localized low-dose rhBMP-2 is effective at promoting bone regeneration in mandibular segmental defects. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2019;107:1491–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arinzeh TL, Tran T, Mcalary J, Daculsi G. A comparative study of biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics for human mesenchymal stem-cell-induced bone formation. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3631–3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie C, Reynolds D, Awad H, et al. Structural bone allograft combined with genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells as a novel platform for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]