Abstract

Purpose

Social isolation, anxiety, and depression have significantly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic among college students. We examine a key protective factor—students’ sense of belonging with their college—to understand (1) how belongingness varies overall and for key sociodemographic groups (first-generation, underrepresented racial/ethnic minority students, first-year students) amidst COVID-19 and (2) if feelings of belonging buffer students from adverse mental health in college.

Methods

Longitudinal models and regression analysis was assessed using data from a longitudinal study of college students (N = 1,004) spanning (T1; Fall 2019) and amidst COVID-19 (T2; Spring 2020).

Results

Despite reporting high levels of belonging pre- and post-COVID, consistent with past research, underrepresented racial/ethnic minority/first-generation students reported relatively lower sense of belonging compared to peers. Feelings of belonging buffered depressive symptoms and to a lesser extent anxiety amidst COVID among all students.

Conclusions

College students’ sense of belonging continues to be an important predictor of mental health even amidst the pandemic, conveying the importance of an inclusive climate.

Keywords: Belonging, Underrepresented racial-ethnic minority students, First-generation students, COVID-19, Mental health, College students

Implications and Contribution.

The rapid shutdown of college campuses in Spring 2020 transformed college students’ psychosocial experiences. Research should continue to explore institutional efforts to promote belonging, especially for URM and FG students, given the accumulating evidence regarding the beneficial effects of belonging, which extends beyond academic outcomes to key public health outcomes.

The devastating outcomes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent shutdown of U.S. college campuses in March 2020 transformed college students’ experiences in a myriad ways [1]. It is well documented that social isolation, depression, and anxiety among college students increased as a result [2], [3], [4], [5], yet little attention has been placed on understanding the psychosocial processes underlying these changes. Furthermore, it is unclear how such underlying processes might vary across key sociodemographic subgroups—such as underrepresented racial/ethnic minority (URM; non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Native) and first-generation (FG) college students (i.e., students with neither parent with a college degree), who have experienced historical exclusion and stigmatization in higher education.

Belongingness, often described as a fundamental human motivation [6], may buffer students from stress and help them engage more meaningfully in their educational experience—a finding borne out of both experimental [[7], [8], [9]] and correlational studies [10,11]. Specifically, students’ uncertainty about their belonging in a new environment has been associated with negative, recursive thought processes that preclude academic and social integration [9,12]. Several studies have explored the positive linkages between students’ sense of belonging and academic outcomes; however, far fewer have focused on mental health.

A growing literature also indicates that students from URM and FG backgrounds report lower belonging [13,14], especially in 4-year colleges [11], which might be particularly pernicious for their mental health. Furthermore, barriers to belonging might be higher for students transitioning into a new college environment [12,15] especially during the pandemic (e.g., first year [FY] students) and the rising racial tensions (e.g., URM students) that coincided with this time period. Given that students’ sense of belonging has potential as an intervention target [[7], [8], [9]] in colleges, understanding the potential buffering effects of belonging on mental health among college students is critical and time-sensitive. Using longitudinal data collected just before (November 2019) and just after the start of the pandemic (May 2020), the current study sought to address the following research questions:

(RQ1) How have college students’ sense of belonging changed before versus after the start of the pandemic overall, and for students who identify as URM, FG, or FY student? (RQ2) Do changes in belongingness pre-versus during the pandemic predict changes in mental health outcomes during the same time period?

Methods and Results

Sample

Data used in this study come from an online survey of undergraduate students from a large, multicampus Northeastern public university in November 2019 (T1) regarding their college experiences. Participants were compensated $5 (Amazon gift card), with an additional 1/100 chance of winning a $100 Amazon gift card. In total, 4,737 participants consented to participate and 4,302 completed the survey in T1.

On March 16, 2020 (amidst Spring break in our study site), all campuses were closed and shifted to remote learning for the remainder of the Spring 2020 semester following the mitigation actions announced by the governor of the state in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Only few select residence and dining halls continued to operate for the limited number of students who remained on campuses during Spring break and the subsequent remote learning period. Students were also strongly discouraged from returning to campus or to off-campus housing following spring break (We also control for students’ residential status prepandemic in our Model (1) to adjust for potential differences because of this context).

To better understand changes in college student experiences across our study site caused by the global pandemic, we designed a follow-up survey. Participants from the T1 survey who consented to be contacted for future research (N = 2,557) were recontacted in May 2020 (T2) to complete a follow-up survey regarding their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. In exchange for participating in the T2 survey, students were compensated $10 (Amazon gift card), with an additional 1/100 chance of winning a $100 Amazon gift card. In total, 1,036 participants consented “yes” to the T2 study; of those, 1,004 completed the T2 survey.

Because our focus in this secondary data analysis was to examine associations between student belonging and mental health especially amidst the pandemic, our analytic sample was restricted to participants who completed both T1 and T2 surveys (N = 1,004). We obtained approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board approval for the current study.

Measures

Belonging

The belonging measure asked students to indicate their agreement with the statement, “I feel like I belong at [college]” (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) (This item was measured on a 5-point scale in T2. To ensure comparability across waves, we standardize this measure in each wave to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1). We standardized this measure to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Belonging uncertainty was measured by asking students, “When you think about [college], how often, if ever, do you wonder: Maybe I do not belong here?” (0 = Never, 1 = Hardly ever, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Frequently, 4 = Always). We reverse coded this measure such that higher values indicate higher levels of belonging. The above two measures capture slightly different psychological constructs with the latter more theory-driven and predictive of well-being [15]; however, because they are highly correlated (α = .8), we combined these two measures to create a belonging composite (we standardized each item within each wave to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 and then compute their average) and reported the results using a standardized composite scale of the above two items. Because the survey was intended to be short to maximize participation and response rates, we chose the most relevant items from the past research literature to capture various dimensions of students’ psychological state of belonging. We therefore included only these two validated items [7,12,15] in our survey.

Mental health

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression 10-item Scale [16], a 10-item scale assessing past-week feelings of depression (e.g., I felt lonely; I felt that everything I did was an effort). Anxiety symptoms were measured using a 6-item anxiety scale [17] assessing past-week feelings of anxiety (e.g., my heart races for no reason; my thoughts are racing). For both depression and anxiety, items were summed across items for each individual. As recommended [16], individuals with depression scores >10 were classified to be at risk for depression (Elevated Depression Risk = 1; 0 otherwise). Similarly, for anxiety, a composite scale of the items was created, individuals’ anxiety risk was coded as follows: 1 = low risk, if the score was <1.30; 2 = moderate risk, if the score was ≥1.30 but <2.10; 3 = elevated risk, if the score was ≥2.10. These cutoff values are standard and scale-appropriate to examine clinically relevant operationalization of elevated depression and anxiety risk [16,17].

Sociodemographic factors

FG status was measured based on student-reported parental education. If neither parent had received a 4-year college degree, the student was classified as an FG student (1 = Yes; 0 = No). URM status was measured based on self-reported race/ethnicity. Based on past research [15,18] on stigmatization and belonging in higher education, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic students, Native American, and Pacific Islanders were classified as URM student (1 = Yes, 0 = No). Similarly, based on past research [7,8] on belonging effects being strongest for stigmatized groups in higher education, we combined URM or FG status to indicate combined group status to test moderations (URM or FG; 1 = Yes, 0 = No). FY student status was self-reported (FY; 1 = Yes, 0 = No). Residential status was measured from a single-item measuring students’ home residence when not in school (1 = Resides in Pennsylvania; 2 = Resides in the U.S., but in a state other than Pennsylvania; 3 = Resides outside of the U.S. [international student]).

Analytic method

For RQ1, we examined mean levels of belonging before (T1) and amidst COVID (T2) overall and by key student sociodemographic characteristics. For RQ2, we explored associations between prepandemic measures of belonging (T1) and mental health amidst COVID (T2) using (1) multivariate regression models adjusting for prepandemic measures and (2) longitudinal models to explore robustness of associations across and within students over time. We used ordinary least squares regression to examine the association between belonging and student mental health outcomes. First, the empirical model takes the form:

| (1) |

where MH it is the depression/anxiety outcome of student i at T2 and BelongComposite it−1 is the focal independent variable of interest that measures prepandemic, students’ belongingness. X i denotes the vector of student characteristics described above, and MH it−1 is the outcome of student i at T1. For models with dichotomous outcome variables (i.e., whether they met criteria for elevated depression risk), the application of ordinary least squares yields coefficient estimates that may be interpreted as linear probabilities.

Second, the empirical model takes the form:

| (2) |

where MH it is the depression/anxiety outcome of student i at each time point and BelongComposite it the focal independent variable of interest, or students’ belongingness also measured in T1 and T2. In this alternative specification, we added student fixed effects (α i) and wave fixed effects (β t) to our regression models. Therefore, the main coefficient of interest on students’ belongingness (γ) in (2) must be interpreted as the association between within-student change in belongingness between T1 and T2 and within-student changes in the outcome variables. In Models (2) and (3) presented in Table 2, we included interaction terms to the above-model specifications to test for moderation of main effects for (1) URM students or FG students and (2) FY students, respectively.

Table 2.

Coefficient estimates and standard errors from regression analyses

| Mental health outcome |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression score | Elevated depression risk | Anxiety score | Elevated anxiety risk | |

| Panel A: multivariate regressions | ||||

| Number of students | 893 | 893 | 949 | 949 |

| Model 1: belonging composite (T1) | −.205 (.230) | −.049∗∗∗ (.018) | −.066∗∗ (.030) | −.056∗∗ (.025) |

| Model 2: first-year student × belonging composite interaction (T1) | .361 (.410) | −.021 (.0335) | −.010 (.0578) | −.010 (.0473) |

| Model 3: underrepresented racial/ethnic minority or first-generation student × belonging composite interaction (T1) | .008 (.417) | .032 (.034) | .015 (.059) | .041 (.048) |

| Panel B: longitudinal models | ||||

| Number of students | 993 | 993 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Model 1: belonging composite | −1.268∗∗∗ (.312) | −.074∗∗∗ (.024) | −.072 (.046) | −.053 (.038) |

| Model 2: first-year student × belonging composite interaction | −2.879∗∗∗ (.300) | −.172∗∗∗ (.0274) | .001 (.040) | −.041 (.033) |

| Model 3: underrepresented racial/ethnic minority or first-generation student × belonging composite interaction | −2.320∗∗∗ (.322) | −.121∗∗∗ (.0296) | −.039 (.043) | −.020 (.038) |

Standard errors in parentheses. Each regression coefficient in the above table is from a separate regression model. To economize on space, we report on coefficients and standard errors on key variables only. All specifications in Panel A above also include students’ race/ethnicity, sex, first-generation college status, residential status, and year in college, as noted in main text. We also control for self-reported baseline (T1) level of the DV of interest across models in Panel A. In Panel B, we include student fixed effects and wave fixed effects such that associations between within-student changes in belonging and DV respectively are captured. To test moderations in Panel B, we used a hybrid model that interacts wave fixed effect with first year (underrepresented racial/ethnic minority or first-generation student). Because we use student fixed effects, all other time-invariant student characteristics are excluded from the models in Panel B; all models used robust standard errors, clustered at the student level.

∗p < .05; ∗∗p < .01; ∗∗∗p < .001.

Results

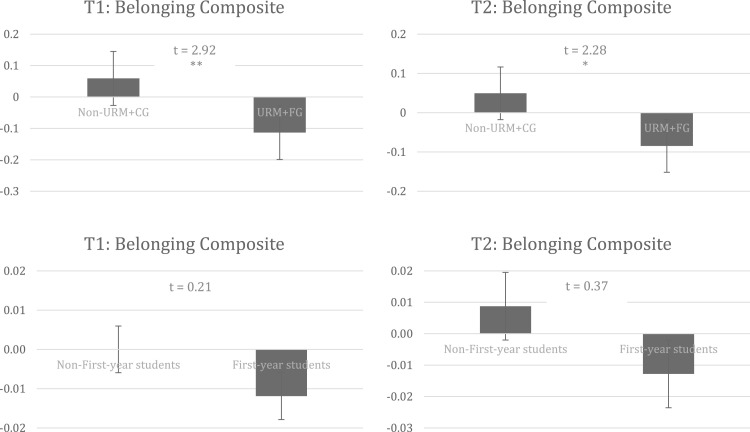

We present descriptive results examining RQ1 in Table 1 . URM and FG students reported significantly lower belonging than their peers (White/Asian/multiracial students and/or continuing-generation students) at both time points (p’s < .05). We did not observe significant differences between FY students and second- to fourth-year undergraduate students (Figure 1 ).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of key variables

| All students |

First-year students |

Underrepresented racial/ethnic minority or first-generation students |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (Standard deviation) | N | Mean | (Standard deviation) | N | Mean | (Standard deviation) | N | |

| Sense of belonging | |||||||||

| Belonging composite (T1) | −.005 | (.906) | 1,002 | −.012 | (.903) | 422 | −.108 | (.940) | 373 |

| Belonging composite (T2) | 0 | (.901) | 999 | −.013 | (.887) | 422 | −.085 | (.893) | 371 |

| Mental health outcomes | |||||||||

| Depression score (T1) | 10.339∗∗∗ | (6.214) | 929 | 9.926∗∗∗ | (6.105) | 393 | 11.328∗∗∗ | (6.311) | 354 |

| Depression score (T2) | 13.122∗∗∗ | (6.928) | 974 | 12.659∗∗∗ | (6.969) | 411 | 13.508∗∗∗ | (6.910) | 364 |

| Depression diagnosis (T1) | .442∗∗∗ | (.497) | 929 | .420∗∗∗ | (.494) | 393 | .525∗∗∗ | (.500) | 354 |

| Depression diagnosis (T2) | .609∗∗∗ | (.488) | 974 | .582∗∗∗ | (.494) | 411 | .637∗∗∗ | (.481) | 364 |

| Anxiety score (T1) | 1.312 | (1.035) | 978 | 1.218 | (1.016) | 410 | 1.408 | (1.025) | 366 |

| Anxiety score (T2) | 1.338 | (1.072) | 991 | 1.211 | (1.049) | 417 | 1.437 | (1.076) | 371 |

| Elevated anxiety risk (T1) | 1.688 | (.822) | 978 | 1.595 | (.792) | 410 | 1.765 | (.827) | 366 |

| Elevated anxiety risk (T2) | 1.716 | (.838) | 991 | 1.626 | (.814) | 417 | 1.782 | (.850) | 371 |

| Other student-level factors | |||||||||

| Sex (male = 1) | .382 | (.486) | 1,002 | .359 | (.480) | 423 | .332 | (.472) | 373 |

| Age (T1) | 19.340 | (1.398) | 1,004 | 18.305 | (.645) | 423 | 19.555 | (1.494) | 373 |

| Underrepresented racial/ethnic minority or first-generation student (URM or FG = 1) | .372 | (.483) | 1,004 | .322 | (.468) | 423 | 1.000 | (.000) | 373 |

| First-year status (FY = 1) | .421 | (.494) | 1,004 | 1.000 | (.000) | 423 | .365 | (.482) | 373 |

| Residential status | 1.970 | (1.073) | 1,004 | 1.000 | (.000) | 423 | 2.180 | (1.172) | 373 |

Residential status was measured as 1 = in Pennsylvania; 2 = in the U.S., but a different state other than Pennsylvania; 3 = outside of the U.S. (international student); 4 = prefer not to answer. Columns 4–6 include all first-year students irrespective of their racial/ethnicity or first-generation college status. Similarly, columns 7–9 include all URM or FG students irrespective of their college year. These categories are not mutually exclusive; rather, the grouping (and associated moderation analyses in subsequent tables) is guided by past theory and empirical literature on college students’ sense of belonging and mental health. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between unadjusted T1 and T2 means.

FG = first-generation; FY = first-year; URM = underrepresented racial/ethnic minority.

∗p < .05; ∗∗p < .01; ∗∗∗p < .001.

Figure 1.

Students’ sense of belonging (standardized composite) by key student characteristics before and amidst COVID-19. Student characteristics include FY students versus all others and URM/FG versus all others. Error bars represent standard errors. T1: N = 1,002 (FY = 422; URM/FG = 373) and N = 999 (FY = 422; URM/FG = 371). ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .001.

In Table 1, we present results examining RQ2. In Panel A, we present results from Model (1) described above. Next, in Panel B, we present results from Model (2). In all models, (1) URM or FG status and (2) FY status were examined as moderators of belonging mental health associations (Models 2 and 3 in Panels A and B). Because we use student fixed effects in Model (2) to examine within-student changes, FY and URM/FG status is time-invariant; thus, to test the moderations here, we used the hybrid method. This is also referred to as the between-within method [19,20] where the time-invariant characteristics interact with the time fixed effects to test for significant moderation.

As shown in Table 2 , belonging was negatively associated with depression amidst COVID (p’s < .05), and to a lesser extent with anxiety across models that provides evidence of buffering effects against adverse mental health for students. For example, a 1 standard deviation increase in students’ belongingness prepandemic is associated with approximately .20 (.06) lower points on the depression (anxiety) score, and a 5-percentage point (.6 points) decrease in the likelihood of a student experiencing elevated depression (anxiety) risk. Similarly, a 1 SD, within-student change in belonging has a buffering effect of 1.3 points and 7-percentage points on that student’s depression scores and likelihood of elevated depression risk, respectively. Significant associations were not observed between changes in level of belonging and anxiety risk in Model 2, a point we return to in the Discussion section. These associations are largely consistent across various sociodemographic groups, with significant moderation observed for URM, FG, and FY students in longitudinal models of depression (p’s < .05; see Panel B, Models 2 and 3).

Discussion

Despite campus closure and social distancing mandates, we did not observe significant changes in students’ reports of belongingness at their college amidst the pandemic in a large, longitudinal sample. Yet concerningly and consistent with past research, URM and FG students reported lower belonging than their peers. Furthermore, greater belongingness was negatively associated with adverse mental health outcomes—such as depression and anxiety. Within-student changes in belonging were protective against depression amidst the pandemic for all students, but especially so for URM, FG, and FY students.

Interestingly, students’ sense of belonging during the early months of COVID and campus closure (May 2020) was not significantly different compared to pre-COVID (n.s.) despite experiencing greater isolation and reporting more depression (p’s < .001). Campus closure, which might have precluded academic and social integration that may have been possible prior to the pandemic, did not significantly impact students’ belongingness or anxiety in college. Widespread social distancing norms on campus amidst the pandemic might have reduced the likelihood of social exclusion. Similarly, students, especially URM/FG/FY students, might have also been buffered from anxiety triggers due to exposure to an online, perhaps safer, learning environment that new students and students with stigmatized student identities are often exposed to in college during nonpandemic times. Continued research and follow-up of college students’ well-being as we emerge out of the pandemic, albeit slowly, is ever more essential.

The large sample size (N = 1,004) with consistent measures of belonging and mental health outcomes elicited at two time points enables rigorous longitudinal analyses; however, this study is not without limitations. First, the longitudinal data come from a single university in the Northeast that limits the generalizability of this study. It is also worth noting that because this study was not originally intended to be a longitudinal survey and was extended to T2 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we had a fairly low response rate (39% of those who consented to participate in future studies beyond T1 responded at T2) for our T2 surveys which may have biased our results. For example, perhaps students experiencing high levels of depression or low levels of belonging were more/less likely to complete the survey. Although it is impossible to predict the exact direction of bias, we note this as a limitation of our study as well.

Indeed, with universities across the country adopting differential mask/vaccine/social-distancing guidelines, the ongoing pandemic warrants more research on these topics. More in-depth studies of belonging and well-being with innovative and continued data collection efforts (e.g., daily diary surveys and ecological momentary assessments beyond the onset of pandemic) may further elucidate these findings and the underlying dynamic processes. Simultaneously, more research exploring college students’ overall mental health and well-being should be carried out in varied contexts to inform institutional programing and outreach efforts [21].

Acknowledgments

We thank Courtney Whetzel for her help with survey administration, project management, and data management efforts. All remaining errors are our own.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

The study receives funding for the survey administration from the Social Science Research Institute, Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, and the College of Health and Human Development at The Pennsylvania State University. We also acknowledge grants NIH/NIDA P50 DA039838 to Lanza and K01AA026854 to Linden Carmichael.

References

- 1.Rogers A.A., Ha T., Ockey S. Adolescents’ perceived socio-emotional impact of COVID-19 and implications for mental health: Results from a U.S.-based mixed-methods study. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuntella O., Hyde K., Saccardo S., Sadoff S. Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2016632118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzales G., de Mola E.L., Gavulic K.A., et al. Mental health needs among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:645–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haliwa I., Spalding R., Smith K., et al. Risk and protective factors for college students’ psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Health. 2021:1–5. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2020.1863413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fruehwirth J.C., Biswas S., Perreira K.M. The Covid-19 pandemic and mental health of first-year college students: Examining the effect of Covid-19 stressors using longitudinal data. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0247999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumeister R.F., Leary M. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeager D.S., Walton G.M., Brady S.T., et al. Teaching a lay theory before college narrows achievement gaps at scale. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E3341–E3348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524360113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy M.C., Gopalan M., Carter E.R., et al. A customized belonging intervention improves retention of socially disadvantaged students at a broad-access university. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaba4677. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walton G.M., Cohen G.L. A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science. 2011;331:1447–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1198364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strayhorn T.L. Routledge; New York, NY: 2018. College students’ sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gopalan M., Brady S.T. College students’ sense of belonging: A national perspective. Educ Res. 2020;49:134–137. doi: 10.3102/0013189x19897622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walton G.M., Cohen G.L. A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92:82–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurtado S., Carter D.F. Effects of college transition and perceptions of the campus racial climate on Latino college students’ sense of belonging. Sociol Educ. 1997;70:324–345. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy M.C., Zirkel S. Race and belonging in school: How anticipated and experienced belonging affect choice, persistence, and performance. Teach Coll Rec. 2015;117:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walton G.M., Brady S.T. In: Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application. Eliot A., Dweck C., Yeager D., editors. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2017. The many questions of belonging; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andresen E.M., Malmgren J.A., Carter W.B., Patrick D.L. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (center for epidemiologic studies depression scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Locke B.D., Buzolitz J.S., Lei P.W., et al. Development of the counseling center assessment of psychological symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62) J Couns Psychol. 2011;58:97–109. doi: 10.1037/a0021282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steele C.M. A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am Psychol. 1997;52:613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allison P.D. 1st ed. SAGE Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. Fixed effects regression models. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allison P.D. 1st ed. SAS Publishing; Cary, NC: 2005. Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Academies of Sciences E . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2021. Mental health, substance use, and wellbeing in higher education: Supporting the whole student. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]