Abstract

Astrovirus infections were detected by enzyme immunoassay in 12 (5%) of 251 stool samples from children with gastroenteritis from Bogota, Colombia. In addition, astroviruses were detected by reverse transcription-PCR in 3 (10%) of 29 stool samples negative for other enteric pathogens collected in Caracas, Venezuela, from children with gastroenteritis. Astrovirus type 1 was the most frequently detected virus.

Astroviruses were first associated with infantile gastroenteritis in 1975 by two independent investigators (9). However, it is only recently, after improvements in diagnostic methods, that the role of astroviruses as etiological agents of infantile gastroenteritis has started to be fully appreciated (5). Astroviruses are small nonenveloped viruses with a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome (9). They have been classified in the family Astroviridae, and other members of the family include viruses of vertebrates and birds (9). In developed countries, astroviruses have been associated with 4 to 10% of endemic diarrheal episodes in children (3, 14, 15, 17); studies of astroviruses in developing countries have found comparable prevalences (4, 6, 16, 18). However, up to 26% of all diarrheal episodes were associated with astroviral infection in a study conducted in a semiclose Mayan community (8). Astroviruses have also been associated with outbreaks of diarrhea in children (11) and in adults (1). In addition, in immunocompromised persons, astroviruses have been reported as the most common viruses detected in patients with diarrhea (5).

Diarrheal infections are among the most common illnesses affecting children under 4 years of age in Colombia and Venezuela. While the importance of rotaviruses as a causal agent of gastroenteritis has been well established in these countries (2, 19), little is known of the importance of other enteric viruses in the etiology of acute diarrhea. In this work, we evaluated the presence of astroviruses in stool samples from children with acute gastroenteritis from Bogota, Colombia, and Caracas, Venezuela, and identified the circulating serotypes.

A total of 251 fecal samples were collected from 251 children with acute diarrhea who sought care in 16 emergency rooms in Bogota between June 1997 and February 1999. All children were under 4 years of age, and samples were collected within 72 h after the onset of symptoms. In addition, 29 selected samples from Caracas, collected from children with acute diarrhea between October 1994 and March 1995, were also tested. These samples were chosen because they were previously known to be negative for rotavirus, enteropathogenic bacteria, and enteropathogenic parasites (19). Samples were stored at −20°C until processed.

All samples collected in Bogota were tested with a commercial astrovirus antigen-detection enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (IDEIA Astrovirus; Dako Diagnostics, Ltd., Ely, United Kingdom). Positive samples were retested at least twice by EIA and further confirmed by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR by using previous cultures of the clarified samples grown in Caco-2 cells for 48 h as described by Mustafa et al. (12). RNA was isolated from cultures (TRIAZOL; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), and the RT-PCR was carried out in one tube with a commercial kit (RT-PCR Access; Promega, Madison, Wis.) with the astrovirus-specific primers Mon 269 and Mon 270 (13). To determine the astrovirus types, the RT-PCR products were sequenced after purification directly with an ABI Prism 377 automatic sequencer, and the sequences were compared to prototype strains in a database. DNA sequences were analyzed by DNAman version 3.2 (Lynnon Biosoft) to produce homology and phylogenetic trees. Phylogenetic analyses were based on a 348-nucleotide sequence within the 449-bp PCR products (13). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method. Samples collected in Caracas were tested for astrovirus only by RT-PCR. In addition, 50 samples which gave negative results by EIA were chosen at random and tested for astrovirus by RT-PCR. The Chi-square test was used to compare prevalence rates among children in different age groups.

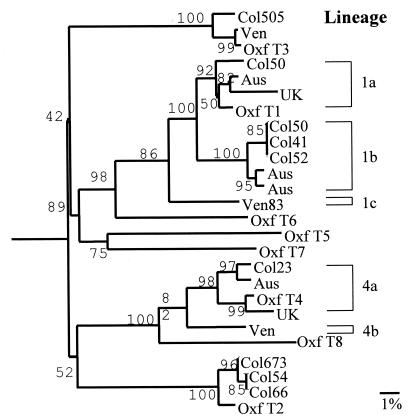

Astrovirus was detected by EIA in 12 (5%) of the 251 samples collected in Bogota. The positive samples were collected in 4 of the 16 emergency rooms studied. Viruses were detected in children 7 to 36 months of age, but prevalence rates were significantly higher (P < 0.01) in children who were 7 to 18 months of age (Table 1). Ten of the samples positive by EIA could be amplified by RT-PCR after cell culture, and the sequence of the RT-PCR products could be determined. Comparison with the sequence of reference astrovirus serotypes in GenBank indicated that five of the Colombian samples could be classified as type 1, three as type 2, and one each as type 3 and type 4 (Fig. 1). From the 29 selected samples from Caracas, 3 (10%) were found to be positive for astrovirus by RT-PCR. Partial sequencing of the RT-PCR products allowed one of the samples to be classified as type 1 (Fig. 1). No positive samples were detected by RT-PCR among the 50 EIA-negative samples chosen at random.

TABLE 1.

Age distribution of astrovirus infection in children from Bogota with acute diarrheaa

| Age group (mo) | No. of samples tested | No. (%) of positive samples |

|---|---|---|

| 0–6 | 47 | 0 |

| 7–12 | 63 | 6 (10) |

| 13–18 | 20 | 3 (15) |

| 19–24 | 53 | 1 (2) |

| 25–36 | 46 | 2 (4) |

| 37–50 | 22 | 0 |

| Total | 251 | 12 (5) |

Prevalence rates were significantly higher in the age groups 7 to 12 and 13 to 18 months combined (P < 0.01).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing the genetic relatedness of astrovirus strains isolated in Colombia and Venezuela to the Oxford astrovirus reference strain of the eight known serotypes and strains from Australia, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela. Strains from the same geographic area diverging less than 1.0% were not included. Bootstrap values, expressed as percentages of 500 replications, are given at the branch points. Strains were arbitrarily named. Oxf, Oxford; Aus, Australia; UK, United Kingdom; Ven, Venezuela. Sequences of strains used for comparison were obtained from the GenBank database (accession no.: Oxford strains, L23513, L13745, L38505, L38506, U15136, L38507, L38508, and Z66541; Australian strains, AF175254, AF175257, U49216, and U49218; United Kingdom strains, S68561 and Z33883; Venezuelan strains, AF211952 and AF211953).

A phylogenetic tree was constructed to study the relationship between the astroviruses isolated in this study and other astroviruses (n = 17) isolated elsewhere (Fig. 1). The Colombian type 1 samples showed up to 7% (23 bases) sequence diversity among themselves and up to 9% sequence diversity with sample Ven835. Based on these sequence variations, three lineages, showing at least 7% sequence diversity, among the type 1 samples isolated could be identified. One lineage, represented by samples 526, 509, and 418, which showed identical sequences, also included samples from Australia; another lineage, represented by sample 503, also included samples from Australia and Europe; the third lineage was represented by sample Ven835 alone. The observed nucleotide sequence changes resulted in amino acid substitutions in relation to the astrovirus serotype 1 Oxford reference strain: samples Col526, Col509, and Col418 differed at position 191 (Ile→Trp) of open reading frame 2 (ORF 2), while sample Ven835 differed at position 92 (Val→Ile). Thus, sample Ven 835 differed at two positions from samples Col526, Col509, and Col418. The 5 base changes found between sample 503 and the Oxford strain were silent. The Colombian type 2 samples showed only 0.6% (2 bases) sequence variation and comprised one lineage, which includes the Oxford serotype 2 reference strain. Samples Col546 and Col664 showed arginine at position 195 of ORF 2, while sample Col673 showed lysine at that position (data not shown). Type 3 sample Col505 and strains from Europe and Venezuela formed only one lineage. Two lineages were found within type 4 samples, one including samples from Colombia, Australia, and Europe, and another represented only by the Venezuelan specimen.

Despite the limited number of samples analyzed, the prevalence rate and age distribution of astrovirus infections observed in Bogota are comparable to those observed for astrovirus infection in other studies (3–6, 14–18). These results suggest that astroviruses may be an important cause of acute gastroenteritis in Colombia. In addition, a study recently conducted in Venezuela failed to identify an enteric pathogen in 41% of the gastroenteritis cases studied (19); our results also suggest that nearly 10% of these undiagnosed gastroenteritis cases could be astrovirus associated. In this study, the highest infection rates were observed in children 6 to 18 months old. The absence of infections observed during the first 6 months of life may be due in part to the presence of transplacental antibodies to astrovirus. The lower infection rates observed in children older than 18 months of age could be due to active immunity from infection, which might confer protection to symptomatic infection even in the presence of several cocirculating types. The results of seroprevalence studies of antibodies to astroviruses conducted in the United States and The Netherlands are consistent with this notion (7, 10). However, much remains to be learned about protective immunity to astrovirus.

The combination of EIAs for sample screening followed by RT-PCR amplification of the positive samples after cell culture (12) allowed identification of the type of more than 70% of the positive samples. Astrovirus type 1 (40% of all infections) was the most frequent type detected, followed by types 2, 3, and 4. Our data are consistent with the type frequency observed by several studies elsewhere (5). Our data also confirmed the genetic variability previously observed among astrovirus types (13, 14). Type 1 astroviruses could be divided into three lineages, and two lineages were observed for type 4 samples. No geographic clustering of the lineages was observed, since the Colombian isolates did not cluster with the Venezuelan strain but with samples from Australia or Europe. However, the specimens of this study showed genetic diversity with predictable amino acid changes for the capsid protein, unlike the results observed by Palombo and Bishop in the Australian specimens (14), in which all mutations were silent. The epidemiological significance of the genetic variations observed among astrovirus types remains to be determined.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been deposited in GenBank and have been assigned accession no. AF211956 to AF211965.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. H. Pujol for helping with the analysis of the sequences.

This work was partially funded by CONICIT grant S1-96001343, Venezuela, and La Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Santafe de Bogota, Colombia. S.M.M. received financial support from RELAB.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belliot G, Laveran H, Monroe S S. Outbreak of gastroenteritis in military recruits associated with serotype 3 astrovirus infection. J Med Virol. 1997;51:101–106. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199702)51:2<101::aid-jmv3>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermeo L, Mogollon D, Ariza F, Barrera J, Jerabek L, Gutierrez M F. Molecular characterization of rotavirus strains obtained from human diarrheic samples and their epidemiological implications. Univ Sci. 1997;4:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bon F, Fascia P, Dauvergne M, Tenenbaum D, Planson H, Petion A M, Pothier P, Kholi E. Prevalence of group A rotavirus, human calicivirus, astrovirus, and adenovirus type 40 and 41 infections among children with acute gastroenteritis in Dijon, France. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3055–3058. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.3055-3058.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaggero A, O'Ryan M, Noel J S, Glass R I, Monroe S S, Mamani N, Prado V, Avendaño L F. Prevalence of astrovirus infection among Chilean children with acute gastroenteritis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3691–3693. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3691-3693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glass R I, Noel J, Mitchell D, Hermann J E, Blacklow N R, Pickering L K, Dennehy P, Ruiz-Palacios G, de Guerrero M L, Monroe S S. The changing epidemiology of astrovirus associated gastroenteritis: a review. Arch Virol (Suppl) 1996;12:287–300. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerrero L M, Noel J S, Mitchell K, Calva J J, Morrow A, Martinez J, Rosales G, Velazquez R, Monroe S S, Glass R I, Pickering L K, Ruiz-Palacios G M. A prospective study of astrovirus diarrhea of infancy in Mexico City. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:723–727. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199808000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koopmans M P G, Bijen M H L, Monroe S S, Vinjé J. Age-stratified seroprevalence of neutralizing antibodies to astrovirus types 1 to 7 in humans in The Netherlands. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:33–37. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.1.33-37.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maldonado Y, Cantwell M, Old M, Hill D, Sanchez M L, Logan L, Millan-Velazco F, Valdespino J L, Sepulveda J, Matsui S M. Population-based prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic astrovirus infection in rural Guatemala. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:334–339. doi: 10.1086/515625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsui S M, Greenberg H B. Astroviruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Lippincott-Raven Press; 1996. pp. 811–824. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell D, Matson D O, Cubitt D, Jackson L J, Willcocks M M, Pickering L K, Carter M J. Prevalence of astrovirus types 1 and 3 in children and adolescents in Norfolk, Virginia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:249–254. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199903000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell D, Matson D O, Jiang X, Barke T, Monroe S S, Carter M J, Willcocks M M, Pickering L K. Molecular epidemiology of childhood astrovirus infection in child care centers. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:514–517. doi: 10.1086/314863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mustafa H, Palombo E A, Bishop R F. Improved sensitivity of astrovirus-specific RT-PCR following culture of stool samples in Caco-2 cells. J Clin Virol. 1998;11:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(98)00049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noel J S, Lee T W, Kurtz J B, Glass R I, Monroe S S. Typing of human astrovirus from clinical isolates by enzyme immunoassays and nucleotide sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:797–801. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.797-801.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palombo E A, Bishop R F. Annual incidence, serotype distribution, and genetic diversity of human astrovirus isolates from hospitalized children in Melbourne, Australia. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1750–1753. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1750-1753.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pang X L, Vesikari T. Human astrovirus-associated gastroenteritis in children under 2 years of age followed prospectively during a rotavirus vaccine trial. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:532–536. doi: 10.1080/08035259950169549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiao H, Nilsson M, Abreu E R, Hedlund K O, Johansen K, Zaori G, Svensson L. Viral diarrhea in Beijing, China. J Med Virol. 1999;57:390–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shastri S, Doane A M, Gonzalez J, Upadhyayula U, Bass D M. Prevalence of astroviruses in a children's hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2571–2574. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2571-2574.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unicomb L E, Banu N N, Azim T, Islam A, Bardham P K, Faruke A S G, Hall A, Moe C L, Noel J S, Monroe S S, Albert J, Glass R I. Astrovirus infection in association with acute, persistent and nosocomial diarrhea in Bangladesh. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:611–614. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urrestarazu M I, Liprandi F, Perez-Suarez E, Gonzalez R, Perez-Schael I. Caracteristicas etiologicas, clinicas y sociodemograficas de la diarrea aguda en Venezuela. Rev Panam Salud Publ Pan Am Public Health. 1999;6:149–156. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891999000800001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]