Abstract

Fusarium head blight (Fusarium graminearum Schwabe), FHB, is considered among the economically significant and destructive diseases of wheat. Thus, the study was worked out at seven sites in southern Ethiopia during the 2019 main cropping year to decide the effects of host resistance and chemical seed treatment on the progress of FHB epidemics and to decide grain yield benefit and yield losses derived from the use of wheat cultivars integrated with chemical seed treatments. The field study was worked out with the integration of two wheat cultivars, including Shorima as well as Hidase, and five chemical seed treatments, including Carboxin, Thiram + Carbofuran, Imidalm, Proceed Plus, and Thiram Granuflo. Twelve experimental treatments were arrayed in factorial arrangement with randomized complete block design. Each experimental treatment was replicated three times and delegated at random to experimental plots within a block. Significant (P < 0.01) variations were observed among the evaluated treatment combinations for rates of disease progress, incidence, severity, the area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC), and yield-related parameters across the locations. Results showed that the lowest incidence was registered on Shorima treated with Thiram + Carbofuran fungicide (27.40%). The lowest mean disease severity was recorded from Shorima integrated with Imidalm (21.23%) and Shorima treated with Thiram + Carbofuran (21.78%). The AUDPC was as low as 211.27, 226.39, and 236.46%-days were recorded on Shorima treated with Imidalm, Thiram + Carbofuran, and Proceed Plus, respectively. The highest disease severity of 57.91% (Hidase) and 27.22% (Shorima), and AUDPC of 552.71%-days (Hidase) and 313.04%-days (Shorima) were recorded from untreated control plots of the two cultivars. Paramount grain yield was found from Shorima treated with Imidalm and Dynamic fungicides, each of which was noted with GY of 4.40 and 4.05 t ha−1, respectively. Results also showed the highest yield losses (21.89 and 23.23%) were computed on untreated control plots of the cultivars Hidase and Shorima, respectively, compared with maximum protected experimental treatment for both cultivars. Moreover, cost-benefit analysis confirmed that Shorima treated with Imidalm exhibited the most prominent net benefit (NB) ($67,381.26 ha−1) and benefit-cost ratio (BCR) (4.43), followed by Shorima treated with Thiram + Carbofuran (NB of $60,837.76 ha−1 and BCR of 3.98). Based on the lowest yield loss and highest economic advantage, the use of Shorima treated with either Imidalm or Thiram + Carbofuran could be suggested to the farmers in the study areas and elsewhere having analogous agro-ecological conditions to manage the disease. However, sole use of chemical seed treatment is not as effective as post-anthesis aerial application up to maturity of the crop. For this reason, post-anthesis aerial application should be considered besides chemical seed treatment for effective management of FHB.

Keywords: AUDPC, Chemical seed treatment, Cost-benefit analysis, Fusarium head blight, Incidence, Grain yield, Severity, Wheat cultivars, Yield loss

AUDPC; Chemical seed treatment; Cost-benefit analysis; Fusarium head blight; Incidence; Grain yield; Severity; Wheat cultivars; Yield loss.

1. Introduction

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is the subsequent most significant staple crop globally, next to maize (Zea mays L.). According to the report of FAOSTAT (2018), the crop has been cultivated over 210 million hectares of land and produced over 800 million tons grain yield. FAO et al. (2018) and USDA (2018) also reported that the world's one-third of the population consumed wheat as a staple food in their day-to-day lives. Wheat is one of the vital cereal crops, which accounts for 18.23% (cultivated areas) and 19.80% (production), following Tef (Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter) in Ethiopia (CSA 2018). The crop is worthy for its nutrient nourishment for human beings as a portion of food, livestock feed, and source of income for many subsistence farmers and investors (Dunwell 2014a; Alicia and Holopainen-Mantila 2020; FAO 2020). In Ethiopia, wheat contributes to the national economy through food security and market share within the country (CSA 2018; Anteneh and Asrat 2020; Chernet and Mamaru 2020).

In Ethiopia, previously the crop is produced only under the rain-fed condition in the highland areas. Now a day, the crop is produced under irrigation conditions with residual rainfall supplementation in the lowland areas of the country. Thus, the crop is produced in a wide range of agro-ecological areas, low (under irrigation conditions) to high altitudes (under rainfall conditions) (CSA 2018; MoANR and EATA 2018). Land preparation is mainly performed by oxen-driven (highland areas) and machinery (lowland areas) in the country. Currently, the use of machinery is extended to highland areas of the country, especially in the highlands of Arsi and Bale, the Oromiya regional state. In the aforementioned areas, the use of combine-harvester is also well-known (Gete et al., 2006; MoANR and EATA 2018). Crop rotation systems chiefly prevailed by cereals (wheat and barley), pulse (faba bean), root crop (Irish potato), and vegetable (head cabbage) in highland areas and cereals (maize and tef) and vegetables (head cabbage, tomato, and onion) in lowland areas (Amanuel et al., 2000; Asefa et al., 2004; Ahmad 2013; MoANR and EATA 2018; Negash et al., 2018; Admasu et al., 2020). In the country, wheat was cultivated on areas of more than 1.75 million hectares of land and production of 4.84 million tons of grain yields during the 2018 cropping year (CSA 2018). Likewise, the crop is cultivated over 150 thousand hectares of areas and brings more than 400 thousand tons of grain productions in the study areas, southern Ethiopia (CSA 2018; MoANR and EATA 2018). This signifies that wheat is widely produced next to tef concerning production and distribution and highly participating in the food security and market share within the country (CSA 2018; Anteneh and Asrat 2020; Chernet and Mamaru 2020).

Despite its many uses, the mean productivity of wheat per unit area is low in Ethiopia (2.77 t ha−1) (CSA 2018) in general and southern Ethiopia (2.66 t ha−1) in particular. In addition, the productivity of wheat was reached more than 7 t ha−1 under research and more than 4 t ha−1 under farmers’ field conditions, as reported by MoANR and EATA (2018). But, mean wheat productivity per unit area has reached 3.77 t ha−1 in the world (FAOSTAT 2018). The low productivity, as identified by diagnostic studies, is mainly attributed to biotic, abiotic, socioeconomic constraints and improper crop management practices in wheat-producing countries of the world (Zegeye et al., 2001; Ayele et al., 2008; Dunwell 2014b). Among fungal diseases, Fusarium head blight (FHB), caused by Fusarium graminearum (Schwabe) or wheat head scab (Teleomorph Gibberella zeae (Schwein.) Petch), is a prevalent Fusarium species and devastating disease of wheat, barley, oats, triticale, and rye producing countries of the world (Parry et al., 1995; McMullen et al., 1997; Steffenson 2003; Dean et al., 2012).

Typical symptoms of infected grains seem to be thin, small, light, shriveled, shrunken, pre-mature, and shielded with a white or pink down under field conditions. Mycotoxins contamination, especially deoxynivalenol (DON), as identified by a diagnosis of infected grains are the main constraints in quality and quantity yields (Langseth et al., 1995; Andersen et al., 2014; Karasi et al., 2016). Wheat grain yield loss due to FHB was estimated to be 50–70% of the total production in wheat-producing areas of the world, including Canada, the United States, Latin America, and other countries. As reported by McMullen et al. (1997), Windels (2000) Pirgozliev et al. (2003), AFAC (2012), and McMullen et al. (2012), the highest (100%) yield losses have been noticed on the susceptible wheat cultivars. During the 2017 and 2018 cropping years, at Sheka, Kafa, Bench Sheko, South Omo, Wolayeta, Guraghe, Kambata Tembaro, and Hadiya a significant annihilative outbreak has encountered in Ethiopia, as reported by the Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resource and Southern Nation, Nationality and People's Regional state (SNNPRs) of Regional Bureau of Agricultural Offices. The problem continued year after year and was widely disseminated to major wheat-producing areas of the country. About 100% damage/yield loss has been reported at Gurafarda, Adiyo, Semen Bench, Masha, and North Ari districts during the two cropping years.

Fusarium head blight is a monocyclic disease that key origin of infection is infected stubble from the preceding season (Sutton 1982; Pereira et al., 2004; Gilbert et al., 2008; Dill-Macky 2010). The disease is significantly affected by weather conditions and it is the main factor that influences the FHB epidemic development. Fusarium head blight frequently occurs in mid-to-high altitudes, having high humidity, of wheat-producing areas of the world. Sutton (1982), Trail et al. (2002), Kriss et al. (2010) and Karasi et al., (2016) reported that the temperature of 15–30 °C and high humidity of 60–90% is optimum conditions for conidial and ascospores germination and development during the epidemic periods. Thus, effective FHB management approaches should be directed on consideration of the pathosystem constituents, host-pathogen-environment interactions. To this effect, several management approaches for FHB have been carried out so far and reported worldwide, including removal of crop residues, deep plowing, intercropping with legume crops, crop rotations, cultivation of moderately resistant crop varieties, seed treatment, and foliar sprays of fungicides (Pirgozliev et al., 2003; Karasi et al., 2016; Shude et al., 2020). The use of cultural management may not sufficient to manage the disease as of economically devastating disease of the crop within a short time during the growing periods. Due to this, most previous research entirely depends on the use of fungicides to manage FHB worldwide (Gilbert and Haber 2013; Ghimire et al., 2020; Shude et al., 2020).

Globally, fungicides including demethylation inhibitor (DMI) class, quinone inhibitor (QoI) class, and triazole-based formulation are widely used as a foliar application to reduce FHB and DON contamination effects on wheat grains Paul et al., (2008); Salgado et al., (2011); McMullen et al., (2012); Wegulo et al., (2015); Palazzini et al., (2017). Furthermore, meta-analyses of fungicide trials revealed that metconazole, prothioconazole + tebuconazole, and prothioconazole were widely used fungicides in the USA and Canada (Paul et al., 2010; Paul et al. 2008; Paul et al. 2018; Shude et al., 2020). Though unable to prevent infection afterward in the growing period, chemical seed treatment help to prevent seedling blighted caused by Fusarium species, and they involve in escaping the seedlings from becoming blight and dead during the early stage of the crop. As reported by Dawson and Bateman (2000), Schoeny et al. (2001), and Krzyzińska et al. (2004), chemical seed treatment having a compatible product preparation upsets the initial growth of plants by suppressing the disease pressure during the early stage, which, successively, will affect growth and development at later stages of the plant and, lastly, yield levels. Everts and Leath (1993), Horoszkiewicz-Janka et al. (2005), and Sawinska and Malecka (2007) also reported that the recognition of the course of protection against seed-borne disease of the crop had better focus on preventing an eminent infection by diseases during early growth stages and, as a result, delay their occurrence until the diseases are no longer very grievous to the crops. The most challenging restraint was to find an efficient chemical seed treatment against FHB where a country likes Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, the management of FHB and kernel smut entirely depends on the practicing of cultural tactics through hand rogueing out and crop rotation (MoANR and EATA 2018).

Planting resistant cultivars are the most profitable and environmentally safe management option for FHB (Ghimire et al., 2020; Shude et al., 2020). However, no wheat variety confers resistance gene against FHB, resistance is conferred via quantitative trait loci (QTLs) (Mesterházy et al., 2005; Dweba et al., 2017; Ghimire et al., 2020; Shude et al., 2020). As resumed by Ban (2000), Cuthbert, et al., 2006, Buerstmayr et al. (2012), and Giancaspro et al. (2016), the most commonly used QTLs for FHB incidence was charted on chromosomes 2AS and 3AL. The authors also reported that QTLs for FHB severity were mainly mapped on chromosomes 2AS, 2BS, 4BL in wheat genotypes. However, the use of resistant cultivars is not confident for every successive year's cultivation of the crop. Previous scholars reported that combinations of more than one management approach had significant effects than a single management approach on FHB (Stephen et al., 2013; Dweba et al., 2017; Paul et al., 2019; Shude et al., 2020). In this regard, Wegulo et al. (2011) and Getachew et al. (2021) reported that individual management options may offer some level of damage reduction duet to FHB under field conditions. According to the authors, integrating chemical control with host resistance can, therefore, provide better control than following individual management options.

As stated earlier, FHB is vital and makes substantial grain yield losses for the farming communities. However, no fungicidal management option lonely or in combination with other management approaches has been practiced by the Ethiopian farmers. The reason was the unavailability of chemical seed treatment in the study areas and the country as well. Nevertheless, some chemical seed treatments, including Carboxin, Carboxin + Thiram + Imidacloprid, Imidacloprid 250 g/kg + Thiram 200 g/kg, Thiram 20% WV + Carbofuran 20% WV, and Thiram 80% SC are available in the country. But, these fungicides have not been recognized by the farmers due to some reasons, the fungicides are mainly registered for other cereal and vegetable diseases than FHB. In addition, to be used these fungicides confidentially by the farmers, research work has not been reported concerning the management of FHB on wheat in the study areas and the country as well.

Therefore, generating empirical field data from the aforementioned chemical seed treatments are pre-requite regarding reasonable and use as a part of integrated management component in integration with cultivar resistance having various levels of response to FHB. Also, evaluation of cultivar resistance and chemical seed treatment for FHB in areas where the environmental conditions are conducive for the epidemic advance of FHB may help in determining the effectiveness of the intended management approaches. Therefore, the objectives of the study were to decide the effects of host resistance and chemical seed treatment on the progress of FHB epidemics and to decide grain yield benefit and yield losses derived from the use of integration of wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments in southern Ethiopia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Descriptions of experimental sites

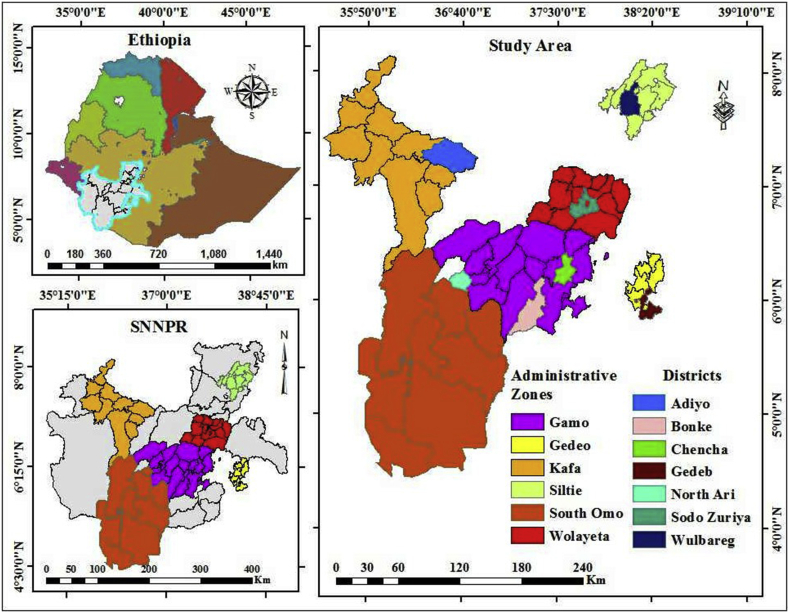

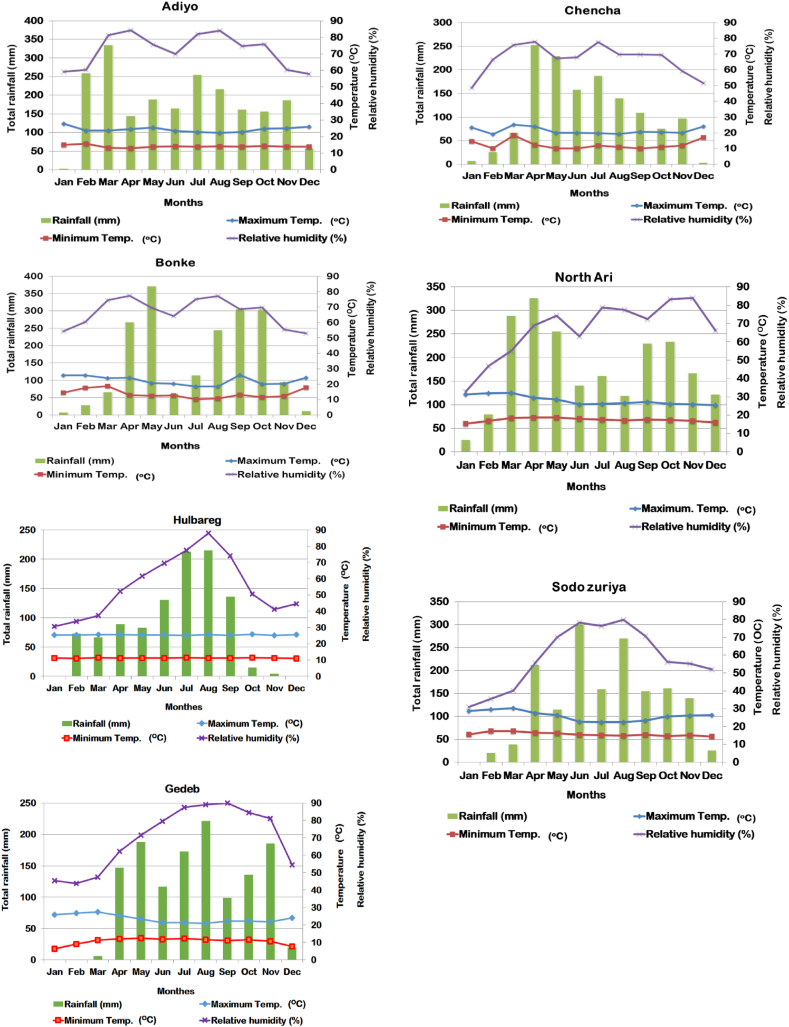

The field study was worked out at seven different locations in SNNPRs in the course of the 2019 main cropping year. The locations include Adiyo, Bonke, Chencha, Gedeb, Hulbareg, North Ari, and Sodo Zuriya. These locations constituted in Kafa (Adiyo), Gamo (Bonke and Chencha), Gedeo (Gedeb), Silte (Hulbareg), South Omo (North Ari), and Wolaita (Sodo Zuriya) administrative zones in SNNPRs, Ethiopia. The locations are selected based on the production potential and importance of FHB during the production season. Figure 1 showed the details of the geographical locations of the experimental sites. In Sodo Zuriya, Gedeb, Hulbareg, North Ari, Adiyo, Chencha, and Bonke, an altitude of 2116, 2245, 2304, 2391, 2400, 2667, and 2786 m above sea levels were registered at the study sites, respectively. The location receives rainfall two times within a production season. March to May is known as the short rainy season, and July to November is known as the long rainy season, the main production season. Accordingly, about 25% of the total annual precipitation is covered under the short rainy season, whereas 45% of the annual precipitation is covered under the main rainy season (Belay et al., 1998). Details of weather conditions, including average monthly maximum and minimum temperatures, total precipitation, and relative humidity for experimental locations for the period of the production season are presented in Figure 2. The weather data for the areas were received from the Ethiopian Meteorological Agency at Hawassa Branch for the 2019 cropping year. In the experimental sites, the soil is characterized by diversified physic-chemical properties. In Hulbareg, Gedeb, North Ari, and Sodo Zuriya, the soil is characterized by a moderately acidic pH (5.8–6.2) with low organic matter contents of 0.83, 2.50, 4.96, and 5.75%, and a textural class of sandy-loam, clay-loam, clay-loam, and sandy-loam, respectively. At Adiyo, the soil is a strongly acidic pH (5.1), comparatively high organic matter contents (11.56%), and clay-loam in textural class. The soil at Bonke and Chencha is distinguished by a strongly acidic pH (4.9 and 5.3, respectively) and low organic matter contents (0.25% and 1.05%, respectively). In addition, the soil textural class is sandy-loam at Bonke and Chencha (MoANR and EATA 2016). Fabe bean was a precursor crop at experimental fields of Bonke and Chencha, while wheat was recorded as a precursor crop for experimental fields of Hulbareg, North Ari, Adiyo, and Sodo Zuriya. Barley was a precursor crop planted at Gedeb.

Figure 1.

Map showing Ethiopian, SNNPRs, and experimental locations for Fusarium head blight in the course of the 2019 cropping year.

Figure 2.

Average monthly maximum and minimum temperatures (oC), total annual precipitation, and relative humidity (%) in Adiyo, Bonke, Chencha, Gedeb, North Ari, Hulbareg, and Sodo Zuriya districts in southern Ethiopia in the course of the 2019 cropping year.

2.2. Treatments, experimental design, and agronomic measures

The experiment has carried out under field conditions, and natural inoculation was regarded to be the base of inoculum during the study. The study has conducted using a combination of two wheat cultivars and five seed treatment fungicides. The cultivars include Shorima and Hidase, which are currently present in the study areas, and exhibited different levels of resistance to major diseases of wheat (MoANR and EATA 2018; Getachew 2020). Shorima (ETBW5483) and Hidase (ETBW5795) cultivars are characterized as averagely resistant and highly vulnerable to major diseases of wheat, respectively. Wheat seeds were got from the Kulumsa Agricultural Research Center, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research. The five seed treatment chemicals were Carboxin, Dynamic 400 FS, Imidalm T 450 WS, Proceed Plus 63% WS, and Thiram Granuflo 80 SC. These fungicides are registered and are currently used as a seed treatment for different crops (Table 1). The experimental treatments have comprised of a combination of two wheat cultivars and five chemical seed treatments plus untreated control for each of the wheat cultivars. The experimental treatments were arrayed in, two wheat cultivars x five chemical seed treatments, factorial arrangement with randomized complete block design sole and in combination, organizing a total of 12 experimental treatments comprising the untreated controls. Each experimental treatment was replicated three times and delegated at random to experimental plots within a block.

Table 1.

Characteristic features of chemical seed treatments tested for the management of Fusarium head blight across the locations in the study areas, southern Ethiopia, during the 2019 main cropping year.

| Fungicide (Trade name) | Year of Registered | Active ingredient | Product formulation | Mode of action | Host crop | Target disease | Application rate per 100 kg of seed | Registrant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxin | 2006 | Carboxin | Wettable powder | Contact | Maize, sorghum, Wheat and barley | Soilborne diseases and insect pests | 400 g | Chemtex P.L.C. |

| Dynamic 400 FS | 2016 | Thiram 20% WV + Carbofuran 20% WV | Flowable concentrate | Contact + Systemic | Maize, sorghum, Wheat, barley, rice, cotton and sunflower | Soilborn diseases, seedling blight, nematodes and rice bakanae | 200–250 ml | Lions International Trading P.L.C. |

| Imidalm T 450 WS | 2010 | Imidaclopride 250 gm/kg + Thiram 200 gm/kg | Wattable powder | Systemic + Contact | Maize, sorghum, Wheat and barley | Soilborn diseases and insect pests | 450 g | Chemtex P.L.C. |

| Proceed Plus 63% WS | 2014 | Carboxin + Thiram + Imidacloprid | Wattable powder | Contact + Systemic | Cereal and Vegetables | Soilborn diseases and seedling blight | 200 g | Mekamba P.L.C. |

| Thiram Granuflo 80 SC | 2005 | Thiram 80% SC | Suspension concentrate | Contact | Soilborn diseases and insect pests | 200 ml | T.M. Global Business Services P.L.C. |

Source: Data were sourced and organized from (MoANR, 2018) and products package booklet.

The experiment was assembled with a gross area of 6.8 m × 27.1 m. The overall field size was 184.28 m2. A component plot size was 1.6 m × 1.8 m and consisted of seven rows with an inter-row of 0.25 cm. Each of the adjacent blocks and plot was spaced at 0.5 and 1.0 m, respectively. Seed treatment was made based on the company recommendation rate of seeds using a shaking device to ensure proper adhesiveness (Table 1). Untreated seeds were reserved for each wheat cultivar as control. Land preparation was performed using oxen-driven material with three (Bonke and Chencha) to four (Gedeb, Hulbareg, North Ari, Adiyo, and Sodo Zuriya) times plowing frequencies depending on the soil softness and/or hardness. Seed sowing was achieved on 27th (at Sodo Zuriya) July and 5th (at North Ari) of August 2019 during the growing period. The sowing date of the other locations was performed between these dates. The seeds were sown at the soil depth of 3 cm and drilled along the rows. The treated seeds were stayed for 24 h, before sowing. Inorganic blended Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Sulfur fertilizer at the rate of 100 kg ha−1 was added at the time of planting. On the other hand, Nitrogen fertilizer at the rate of 200 kg ha−1 was applied when one-third of it was applied during planting and two-third on 35-days after planting. All other necessary field management practices were executed uniformly for all treatments with recommended practices as suggested by MoANR and EATA (2018). Rex® Duo [Epoxiconazole + Thiophanate-methyl] at the rate of 0.5 L ha−1 with 300 L of dilution water was applied for management of wheat rusts and septoria leaf blotch, including the control plots.

2.3. Disease assessment

Incidence and severity of FHB were monitored every 10-days intervals. Incidence and severity scores were begun with the observation of the disease symptoms for the first time on the spikelet at the Zadok growth stage (ZGS) of 60 (Zadoks et al., 1974). The disease scores were stopped as soon as the crop reached physiologically mature, which was approximately at the ZGS of 90. Twenty randomly nominated and marked wheat plants were used to determine the incidence and severity of FHB. This is taken from the five internal rows of each plot for the duration of the assessment. The wheat plants once selected were tagged and maintained up to the last assessment dates. Fusarium head blight incidence was ascertained as the average percentage of all diseased plants per the whole plant and rated inside the plot as indicated by the following formula suggested by Campbell and Madden (1990) (Equation 1).

| (1) |

Fusarium head blight severity was commemorated using a scale of 1–100% as suggested by Robert and Marcia (2011). In each location, incidence and severity were assessed five times in the course of assessments. The average severity values derived from 20 appraised plants were exploited for data examination. Likewise, the area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) was calculated to decide the effects of the experimental treatments on FHB progress during the growing period. The AUDPC (Equation 2) indicated that the progress and accruement of disease on the entire or part of the plant in the course of the epidemic development. It was worked out from severity data estimated at various dates after disease onset for each experimental treatment as proposed by Campbell and Madden (1990).

| (2) |

where n is the total number of disease assessments, ti is the time of the ith assessment in days from the first assessment date and xi is the disease severity of FHB at the ith assessment. The unit of AUDPC is %-days since severity (x) is articulated in percent and time (t) in days.

2.4. Yield parameters and relative yield loss assessment

Yield parameters, including grain yield (GY) and thousand seed weight (TSW), were considered and harvested from the five middle rows. Grain harvesting was done by hand and undertaken on 140 and 165-days after planting (ZGS of 100) at Sodo and Bonke, respectively. The date of harvesting for the remaining locations was found between 140 and 165-days after planting. The plot-wise collected GY has transformed into t ha−1, and a TSW was also measured in gram (g) for experimental each treatment. During harvesting, the moisture content tester was used to find out the moisture content of the seed. Sequentially, GY was corrected to a storable moisture content of 12.5% using the method suggested by Taran et al. (1998). Thousand seed weights were randomly sampled from the storable grains of each experimental treatment and measured using an electrical sensitive balance device. In addition, relative GY losses were determined to sympathize with the influence of FHB pressure on tested wheat cultivars. It was determined for each experimental treatment following the procedure proposed by Robert and James (1991) (Equation 3).

| (3) |

where, Ybt = mean yield of the best experimental treatment in the experiment (comparatively highly protected plot) and Ylt = mean yield of the other experimental treatments (low to medium protected plots). Likewise, the relative yield for each experimental treatment was intended as the ratio of the yield obtained from individual treatment compared with the maximum yield obtained under treatment considered and multiplied by 100%.

2.5. Data analysis

For the study parameters (disease scores and yield-associated traits), analysis of variance (ANOVA) was achieved using the GLM procedure of SAS version 9.3 (SAS 2014). A Monomolecular [ln (1/1–y)] epidemiological model was applied to estimate disease progress rates for the intended experimental treatments (Van der Plank, 1963). Disease severity records were changed over time to find out the disease progression rate. Then, the monomolecular model was employed to estimate the rate of disease progression (r) and the intercept (point) of the disease progress curve from the slope of the regression line. The five locations are assumed to be different environments, and for this reason, Bartlett's chi-square test was applied to examine the heterogeneous error variance (Gomez and Gomez, 1984). Bartlett's chi-square test for the error variances of the study parameters, disease scores, and yield-associated traits, exhibited there was heterogeneity of the recorded data across the locations. Even if Bartlett's chi-square test exhibited heterogeneous for the recorded data, independent data analysis was applied due to some reasons. For this reason, combined data analysis was performed for the study parameters (disease scores, and yield-associated traits). The treatment means separations were achieved using Fishers protected least significant difference (LSD) test at 5% probability level (Gomez and Gomez, 1984). Associations of FHB severity and AUDPC with GY of wheat were appraised using simple correlation analysis. The Determined Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were employed as indicators for the strength and/or weakness of the associations. Similarly, the relationship between the disease scores and GY was examined employing linear regression for estimating the GY loss in wheat production (Minitab, Release 15.0 for windows® 2007).

2.6. Cost-benefit analysis

To ascertain the cost-benefit analysis for the intended management option, integrating cultivars resistance and chemical seed treatments, the procedure suggested by CIMMYT (1988) was employed. Total input cost of production, gross benefit, net benefit (NB), and benefit-cost ratio (BCR) were considered during cost-benefit analysis. The total input cost (extra expenses for disease and trial management) was found out from the summation of all costs (variable + fixed input costs) used in the study. Fertilization, land rent, weeding, and harvesting wages were considered as fixed costs of production. While the knapsack sprayer, fungicides, and labors for fungicide spray were considered as variable costs of production. The gross benefit was concluded by multiplying of commercialized price and GY. The NB was computed as subtracting the total costs from the gross benefit. In addition, the BCR was computed as the proportion of BCR (numerator) and total costs (denominator). Before cost-benefit analysis, the statistical significance was examined to collate the mean GY incurred between treatment combinations. In this regard, noteworthy variations between experimental treatment means were detected and the collected financial data were subjected to cost-benefit analysis. The actual GY was corrected by 10% down to examine the GY departure between the farmers’ activity and the research work that could expect from similar treatment.

The costs of Imidalm ($7.95 kg−1), Carboxin ($9.45 L−1), Thiram Granuflo ($9.45 L−1), Thiram + Carbofuran ($15.80 kg−1), and Proceed Plus ($15.80 L−1) were obtained from the prevailing local market ($1 United State = 31.45 Ethiopian Birr during merchandising). The shopping unit value of the knapsack sprayer was $ 38.16 as information gathered from Addis Ababa (central market), Ethiopia. Around North Ari, the labor cost man−1 day−1 was $1.11. Labor cost man−1 day−1 around Adiyo, Bonke, Gedeb, and Sodo Zuriya was $1.58 for each of them. About $1.90 labor cost man−1 day−1 for each location was paid around Chencha and Hulbareg during the growing period. About $78.49, 78.49, 127.19, 127.19, 143.08, 174.88, and 174.88 expense of land rent per one growing period was paid off per hectare in North Ari, Gedeb, Adiyo, Bonke, Chencha, Hulbareg, and Sodo Zuriya during the study time, respectively. As the Regional Bureau of Agriculture office presented, the purchasing prices of NPS blended and urea fertilizers were $42.43 and 39.11 per 100 kg bundle during sowing time, respectively. During marketing, the cost of the grain per kg, which was sold at Gedeb, Adiyo, Sodo Zuriya, North Ari, Bonke, Hulbaredg, and Chencha, was $0.48, 0.51, 0.64, 0.67, 0.76, and 0.79, respectively. All costs, expenditure costs, and benefits found were transformed into a hectare for finding out the cost-benefit analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of variance

The combined ANOVA for disease scores as well as yield-related traits revealed that there were various levels of variations between the experimental locations, wheat cultivars, chemical seed treatments, and interactions between and among the locations, wheat cultivars, and chemical seed treatments (Table 2). Highly significant (P < 0.0001) variation was perceived among the study locations for the mean squares of disease incidence, severity, AUDPC, disease progress rate, TSW, and GY due to interactions of wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments. Mean square analysis showed that significant variations of P < 0.05 (TSW), P < 0.05 (GY), and P < 0.0001 (all disease parameters) were observed between the evaluated wheat cultivars. Also, the mean square analysis revealed substantial variations for all study parameters among the tested chemical seed treatments. Thus, P < 0.01 for thousand seed weight, P < 0.001 for GY, and P < 0.0001 for all disease scores parameters. Interaction (P < 0.0001) effects between wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments, except for thousand seed weight, were also examined with various levels of significant variations where P < 0.01 for GY to P < 0.0001 for disease severity and AUDPC. Furthermore, the mean squares analysis indicated that no interaction effects were discovered among the locations, wheat cultivars, and chemical seed treatments for the study parameters, except for disease progress rates, severity, and AUDPC (Table 2). Overall, combined ANOVA for the evaluated experimental treatments, locations, and interactions of wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments, showed the highest mean square values of all the study parameters. This indicates that the tested experimental treatments for the study parameters responded similarly in all locations. The lowest mean square values of all the study parameters across the experimental locations could be ascribed to the different responses of the tested experimental treatments for the disease scores and yield-related traits or due to the differences among the locations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean square values for all study parameters as influenced by the integration of breed wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments under crosswise assessment in southern Ethiopia during the 2019 main cropping year.

| Source of variation | DF | DIf (%) | DSf (%) | AUDPC (%-days) | DPR (units day−1) | TSW (g) | GY (t ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOC | 6 | 31514.96∗∗∗∗ | 21046.44∗∗∗∗ | 2289445.44∗∗∗∗ | 0.0879∗∗∗∗ | 1818.89∗∗∗∗ | 124.63∗∗∗∗ |

| Block (within the location) | 14 | 164.04ns | 148.33ns | 23105.47ns | 0.8312ns | 37.78ns | 1.09ns |

| CUL | 1 | 23007.32∗∗∗∗ | 25666.52∗∗∗∗ | 1862057.21∗∗∗∗ | 0.0668∗∗∗∗ | 89.00∗ | 10.47∗∗ |

| FUN | 5 | 1059.16∗∗∗∗ | 1415.56∗∗∗∗ | 113166.42∗∗∗∗ | 0.0081∗∗∗ | 98.01∗∗ | 4.35∗∗∗ |

| LOC ∗ CUL | 6 | 3140.60∗∗∗∗ | 1747.91∗∗∗∗ | 163425.71∗∗∗∗ | 0.0083∗∗∗ | 158.68∗∗∗∗ | 3.60∗∗ |

| LOC ∗ FUN | 30 | 213.26∗∗∗∗ | 279.18∗∗∗∗ | 27826.01∗∗∗∗ | 0.0043∗∗∗ | 58.56∗∗ | 0.88ns |

| CUL ∗ FUN | 5 | 485.81∗∗∗ | 527.49∗∗∗∗ | 60207.94∗∗∗∗ | 0.0066∗∗∗ | 3.69ns | 0.41∗∗ |

| LOC ∗ CUL ∗ FUN | 30 | 142.43ns | 161.38∗∗∗ | 11389∗∗ | 0.0045∗∗∗∗ | 21.82ns | 0.46ns |

| Pooled error |

154 |

60.24 |

68.02 |

5973.59 |

2.1905 |

27.32 |

0.99 |

| Grand mean | 40.05 | 34.31 | 320.28 | 0.0450 | 35.63 | 3.62 | |

| CV (%) | 19.38 | 24.04 | 24.13 | 32.88 | 14.66 | 27.53 |

DF = Degree of freedom; DIf = Disease incidence at final date of assessment; DSf = Disease severity at final date of assessment; AUDPC = Area under disease progress curve; DPR = Disease progress rate; GY = Grain yield measured in t ha−1; TSW = Thousand seed weight; LOC = Location; CUL = Cultivar; FUN = Fungicide; Location ∗ Cultivar = Interaction effect of location and cultivar; Location ∗ Fungicide = Interaction effect of location and fungicide; Cultivar ∗ Fungicide = Interaction effect of cultivar and fungicide; Location ∗ Cultivar ∗ Fungicide = Interaction effect of location, cultivar and fungicide; ∗∗∗∗ = Significantly different at P < 0.0001; ∗∗∗ = Significantly different at P < 0.001; ∗∗ = Significantly different at P < 0.01; ∗ = Significantly different at P < 0.05; ns = Not significant (P > 0.05); CV = Coefficient of variation (%).

3.2. Rate of fusarium head blight epidemic development

Estimation of disease progression rates and parameters for FHB showed significant (P < 0.001) variations among the tested experimental treatments across the locations (Tables 2 and 3). During the epidemic period, FHB disease development was greater on untreated control than treated plots of the two cultivars in all locations. Among the locations, the mean highest (0.1538 units day−1, R2 = 94.60%) rates of disease progression were recorded at North Ari, followed by Adiyo (0.0395 units day−1, R2 = 88.40%) and Sodo Zuriya (0.0367 units day−1, R2 = 88.10%). Regarding experimental treatments, Hidase cultivar exhibited the lowest (0.0223 unit day−1, R2 = 84.20% on Imidalm) and the highest (0.0917 unit day−1, R2 = 96.10% on untreated control) rates of disease progression compared with Shorima cultivar (0.0167 units day−1, R2 = 92.50% on Imidalm and 0.0422 units day−1, R2 = 98.50% on untreated control) under crosswise assessment. In this regard, planting Shorima cultivar reduced rates of disease progression by 25.11 and 53.98% compared with Hidase treated with Imidalm and untreated control plots, respectively (Table 3). Thus, rates of disease progression were reduced on Imidalm treated plots, followed by Thiram + Carbofuran treated plots for Shorima (0.0123 units day−1) and Hidase (0.0267 units day−1) cultivars than the other chemical seed treatments and untreated control plots. The overall results showed that the integrations of cultivar resistance and chemical seed treatments significantly lowered the rates of FHB progression that the untreated controls across the locations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean rates of disease progression and estimated parameters using the monomolecular model for Fusarium head blight epidemic under integrated management manners in the seven locations, southern Ethiopia, during the 2019 main cropping year.

| Treatment combination |

Disease severity (%)a |

Disease progress rate (units day−1)b | SE of rateb | SE of interceptb | R2 (%)c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | DSi (%) | DSf (%) | |||||

| Adiyo | 12.94 | 38.07 | 0.0395 | 0.0045 | 0.0437 | 88.40 | |

| Bonke | 2.74 | 10.96 | 0.0102 | 0.0023 | 0.0236 | 90.10 | |

| Chencha | 3.31 | 12.26 | 0.0112 | 0.0024 | 0.0220 | 93.50 | |

| Gedeb | 7.48 | 27.69 | 0.0323 | 0.0026 | 0.2035 | 90.20 | |

| Hulbareg | 7.92 | 31.68 | 0.0312 | 0.0223 | 0.2316 | 96.50 | |

| North Ari | 20.85 | 83.38 | 0.1538 | 0.0026 | 0.0635 | 94.60 | |

| Sodo Zuriya |

10.84 |

36.14 |

0.0367 |

0.0035 |

0.0556 |

88.10 |

|

| Wheat cultivar | Chemical seed fungicide | ||||||

| Hidase | Carboxin | 13.24 | 47.49 | 0.0674 | 0.0207 | 0.0436 | 94.50 |

| Hidase | Thiram + Carbofuran | 10.53 | 37.81 | 0.0259 | 0.0281 | 0.0558 | 93.80 |

| Hidase | Imidalm | 8.69 | 31.34 | 0.0223 | 0.0056 | 0.0286 | 91.30 |

| Hidase | Proceed Plus | 13.07 | 46.92 | 0.0784 | 0.0222 | 0.0590 | 95.10 |

| Hidase | Thiram Granuflo | 12.47 | 44.95 | 0.0517 | 0.0134 | 0.0325 | 96.10 |

| Hidase |

Untreated |

15.90 |

57.91 |

0.0917 |

0.0187 |

0.0632 |

84.20 |

| Shorima | Carboxin | 7.95 | 27.22 | 0.0320 | 0.0069 | 0.0531 | 92.50 |

| Shorima | Thiram + Carbofuran | 5.92 | 21.78 | 0.0268 | 0.0091 | 0.0467 | 96.60 |

| Shorima | Imidalm | 5.67 | 21.23 | 0.0167 | 0.0087 | 0.0465 | 97.40 |

| Shorima | Proceed Plus | 6.49 | 24.05 | 0.0281 | 0.0081 | 0.0483 | 96.30 |

| Shorima | Thiram Granuflo | 5.60 | 22.17 | 0.0261 | 0.0089 | 0.0459 | 94.60 |

| Shorima | Untreated | 10.46 | 28.88 | 0.0422 | 0.0093 | 0.0535 | 98.50 |

Initial and final disease severity (DS) of Fusarium head blight recorded at 22 and 62-days after anthesis during the growing period, respectively.

Disease progress rate obtained from regression line of (ln (1/1–y)) disease severity against time of disease assessment; SE = Standard error of rate and parameter estimates (intercept).

R2 = Coefficient of determination for the Monomolecular epidemiological model.

3.3. Disease incidence

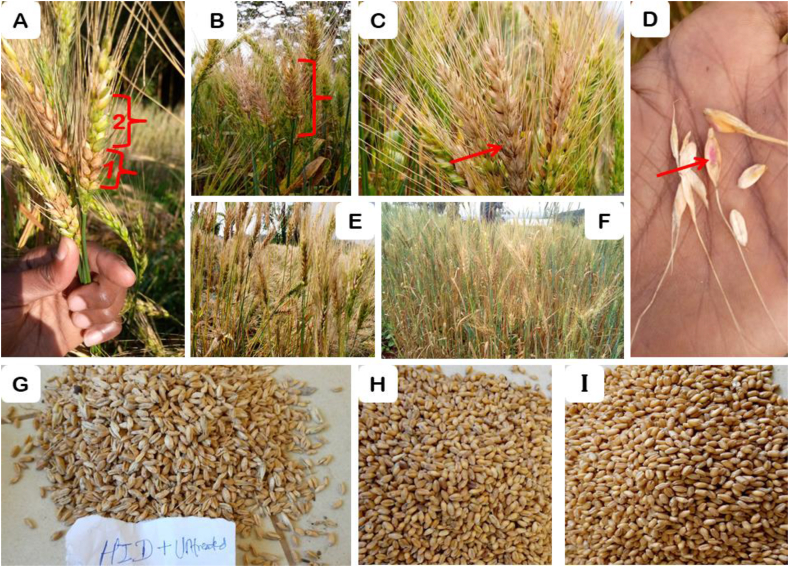

The symptoms comprised of water soaked lesions on spikelets that eventually seem as whited/faded, and pink or orange spore masses. The infected kernels showed shriveled, pre-mature, shrunken, black spherical structures formations, and a whitish-brown visual aspect whereas the remaining spike part still seems green and healthy heads (Figure 3). The combined analysis of disease incidence revealed a significant (P < 0.001) difference amongst the experimental locations (Tables 2 and 4). During the study, typical symptoms of FHB were first noticed on the vulnerable cultivar (Hidase) at ZGS of 60 at North Ari, successor by Hulbareg, Adiyo, Sodo Zuriya, Gedeb, Chencha, and Bonke. However, the highest mean disease incidence (100%) was scored at North Ari. The lowest mean disease incidence was recorded at Bonke (10.93%), which was statistically on par with the mean disease incidence recorded at Chencha (13.52%). Disease incidence was reduced by 53.12, 61.88, 61.91, 67.17, 86.46, and 89.07% at Adiyo, Sodo Zuriya, Hulbareg, Gedeb, Chencha, and Bonke compared with North Ari, respectively. On the other hand, the highest mean FHB incidence (61.59%) was registered from the untreated control plot of the Hidase cultivar. The lowest mean FHB incidence was registered from Shorima treated with Thiram + Carbofuran. However, no statistically significant variations were observed between Shorima treated with Thiram + Carbofuran and Shorima treated with other chemical seed treatments (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Fusarium head blight typical symptom of infected wheat spikes and spikelets in the field. Infected spikes and spikelets with water soaked injuries [A1] and healthy heads were still green on Hidase [A2], completely diseased spike that looks as if whitened/bleached on Hidase [B], black spherical structures (perithecia) formation on Hidase [C], production of pink or orange spore masses [D], Control plots of Hidase [E] and Shorima [F], pre-mature, shrunken and shriveled grain on the cultivar Hidase [G], and pure, well mature and healthy grain of Hidase [H] and Shorima [I] obtained from best-protected plots.

Table 4.

Interaction effects of bread wheat cultivars and seed treatment fungicides on Fusarium head blight incidence, severity, area under disease progress curve, and yield parameters in the seven locations, southern Ethiopia, during the 2019 main cropping year.

| Treatment | DIf (%) | DSf (%) | AUDPC (%-days) | TSW (g) | GY (t ha−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||||

| Adiyo | 46.88b | 38.07b | 266.25c | 29.21e | 2.17d | |

| Bonke | 10.93d | 10.96e | 59.81d | 40.65b | 5.76a | |

| Chencha | 13.52d | 12.26e | 71.74d | 37.34c | 5.59a | |

| Gedeb | 32.83c | 27.69d | 265.87c | 44.77a | 3.64c | |

| Hulbareg | 38.09c | 31.68cd | 384.35b | 31.77d | 2.40d | |

| North Ari | 100a | 83.38a | 807.74a | 25.10e | 0.94e | |

| Sodo Zuriya | 38.12c | 36.14bc | 386.24b | 40.57b | 4.86b | |

| LSD (0.05) |

6.04 |

5.69 |

53.96 |

2.70 |

0.45 |

|

| Wheat cultivar | Chemical seed fungicide | |||||

| Hidase | Carboxin | 51.73b | 47.49b | 426.24b | 34.90b-d | 3.45cd |

| Hidase | Thiram + Carbofuran | 46.03b | 37.81cd | 314.71c | 36.07a-d | 3.70bc |

| Hidase | Imidalm | 37.21c | 31.34de | 317.55c | 37.45a-c | 3.75bc |

| Hidase | Proceed Plus | 49.22b | 46.92b | 415.38b | 34.00cd | 3.18cd |

| Hidase | Thiram Granuflo | 51.85b | 44.95bc | 410.88b | 34.28cd | 3.51b-d |

| Hidase |

Untreated |

61.59a |

57.91a |

552.71a |

33.50d |

2.93d |

| Shorima | Carboxin | 32.95c-e | 27.22e-g | 255.46cd | 35.30a-d | 3.65bc |

| Shorima | Thiram + Carbofuran | 27.40e | 21.78fg | 226.46d | 37.84ab | 4.05ab |

| Shorima | Imidalm | 28.68de | 21.23g | 211.27d | 38.73a | 4.40a |

| Shorima | Proceed Plus | 30.42c-e | 24.05e-g | 226.39d | 35.05b-d | 3.78bc |

| Shorima | Thiram Granuflo | 28.17de | 22.17fg | 273.33cd | 34.98b-d | 3.70bc |

| Shorima | Untreated | 35.36cd | 28.88ef | 313.04d | 35.42a-d | 3.38cd |

| LSD (0.05) |

7.91 |

7.44 |

70.66 |

3.54 |

0.60 |

|

| CV (%) | 19.38 | 24.04 | 24.13 | 14.66 | 27.53 | |

Mean values in the same column with different letters represent significant variation at 5% probability level. DIf = Disease incidence at final date of assessment; DSf = Disease severity at final date of assessment; AUDPC = Area under disease progress curve; TSW = Thousand seed weight; GY = Grain yield; LSD = Least significant difference at a 5% probability level; and CV = Coefficient of variation (%).

3.4. Disease severity

Integration of wheat cultivar and chemical seed treatment exhibited a significant (P < 0.0001) consequence on disease severity across the locations (Tables 2 and 4). ANOVA revealed that the highest (83.38%) mean disease severity was noticed at North Ari. The lowest (10.96%) mean severity was noticed at Bonke. However, the disease severity value observed at Bonke was statistically similar to the value observed at Chencha. At North Ari, planting of wheat cultivar, which severely suffered from the FHB damage, had a severity of 54.34, 56.66, 62.01, 66.79, 85.30, and 86.86% compared with the planting of wheat at Adiyo, Sodo Zuriya, Hulbareg, Gedeb, Chencha, and Bonke, respectively (Table 4). The highest (57.91%) severity indicant was recorded from the untreated control plot of the Hidase cultivar. The lowest (21.23%) mean disease severity has been observed on the cultivar Shorima treated with Imidalm. However, this treatment combination was statistically on part with the value of disease severity observed on Shorima cultivar treated with Thiram + Carbofuran (21.78%) and Shorima cultivar treated with Thiram Granuflo (22.17%).

The overall FHB pressure had comparatively higher at North Ari than other locations. Chemical seed treatments, including Imidalm and Thiram + Carbofuran, showed effectiveness against FHB with consistent results on both Hidase and Shorima cultivars (Table 3). It was observed that integration of wheat cultivar and chemical seed treatment decreased FHB epidemic development, thereby their respective mean disease severity reduces for each cultivar. The mean disease severity was decreased by 17.99% (Carboxin), 18.98% (Proceed Plus), 22.38% (Thiram Granuflo), 34.71% (Thiram + Carbofuran), and 45.88% (Imidalm) related to the untreated control plot of the cultivar Hidase. Similarly, the mean disease severity was reduced by 5.75% (Carboxin), 16.72% (Proceed Plus), 23.23% (Thiram Granuflo), 24.58% (Thiram + Carbofuran), and 26.49% (Imidalm) related to the untreated control plot of the cultivar Shorima.

3.5. Area under the disease progress curve

The variance of analysis conveyed that AUDPC was significantly (P < 0.0001) altered by the interaction effects of experimental treatments across the locations (Tables 2 and 4). According to the results of ANOVA, the highest mean AUDPC value (807.74%-days) was scored at North Ari. Conversely, the lowest mean AUDPC (59.81%-days) was recorded at Bonke. However, the AUDPC value recorded at Bonke was not significantly varied from Chencha, 71.74%-days. At Sodo Zuriya, Hulbareg, Adiyo, Gedeb, Chencha, and Bonke, the use of wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments in an as integrated manner reduced the AUDPC by 52.18, 52.42, 67.04, 67.08, 91.12, and 92.60% compared with North Ari (Table 4). Among the treatment combinations, the mean highest (552.715%-days) AUDPC was noticed on an untreated control plot of the cultivar Hidase. The lowest mean (211.27%-days) AUDPC was noted on the cultivar Shorima treated with Imidam. However, the AUDPC value was not statistically significantly different from a combination of Shorima cultivar with Carboxin, Thiram + Carbofuran, Proceed Plus, and Thiram Granuflo, respectively, including untreated plot.

The overall FHB pressure was comparatively higher on the Hidase cultivar under any combination with chemical seed treatments than the Shorima cultivar in combination with each of the chemical seed treatments. Each wheat cultivar treated with chemical seed treatment has resulted in lesser AUDPC than their comparable untreated control plots. On plots of Hidase cultivar, the mean AUDPC, which was lessened by 22.88%, 24.85%, 25.66%, 42.55%, and 43.06%, was observed on Carboxin, Proceed Plus, Thiram Granuflo, Imidalm, and Thiram + Carbofuran, respectively, compared to the mean AUDPC recorded on untreated control plot. Likewise, the mean AUDPC was reduced by 12.69% (Thiram Granuflo), 18.39% (Carboxin), 27.66% (Thiram + Carbofuran), 27.68% (Proceed Plus), and 32.81% (Imidalm) compared with the mean AUDPC ciphered from an untreated control plot of the cultivar Shorima.

3.6. Yield parameters

The variance of the analysis showed that there was a significant (P < 0.01) variation in the integration of wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments for TSW and GY (Tables 2 and 4). ANOVA for TSW showed the highest (44.77 g) was recorded at Gedeb. The lowest TSW (25.10 g) was observed at North Ari. However, it was not significantly different from the value obtained at Adiyo, 29.21 g (Table 4). Crosswise evaluation of the integration of wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments showed that Bonke (5.76 t ha−1) and Chencha (5.59 t ha−1) was received the highest GY than the other locations. The lowest GY of (0.94 t ha−1) was recorded at North Ari, which was a substantial GY reduction among experimental locations (Table 4). The highest mean GY was achieved from the integration of Shorima and Imidalm (4.40 t ha−1), but it was statistically on par with the integration of Shorima and Thiram + Carbofuran (4.05 t ha−1). The lowest mean GY was suffered from the untreated control plot of Hidase (2.93 t ha−1), which was statistically similar with the mean GY obtained from the untreated control plot of Shorima (3.38 t ha−1) and integration of Hidase with Carboxin (3.45 t ha−1) (Table 4). The mean GY advantage was increased by 7.86% (Proceed Plus), 15.07% (Carboxin), 16.52% (Thiram Granuflo), 20.81% (Thiram + Carbofuran), and 21.87% (Imidalm) over the mean GY obtained from an untreated control plot of Hidase cultivar. In addition, the mean GY benefit was enhanced by 7.40% (Carboxin), 8.65% (Thiram Granuflo), 10.58% (Proceed Plus), 16.54% (Thiram + Carbofuran), and 23.18% (Imidalm) compared with the mean GY received from the untreated control plot of Shorima cultivar.

3.7. Relative yield loss

Results obtained from relative GY losses assessments for every location and experimental treatment are presented in Table 5. Significant variations were observed on GY losses among the locations and experimental treatments. Bonke was exploited as a reference to calculate relative GY loss for the other locations. In this regard, the highest GY losses (83.68%) were recorded at North Ari, followed by Adiyo (62.33%) and Hulbareg (58.33%). On the other hand, Shorima treated with Imidalm and Hidase treated with Imidalm were used as a reference to figure out relative yield loss for other respective treatment combinations. This was due to the integration of the two cultivars with Imidalm resulted in the highest relative yield advantage over the other treatments (Table 5). Comparatively, GY loss was reduced on wheat cultivars integrated with chemical seed treatments over the untreated control plots. Overall, the maximum GY losses (21.89 and 23.23%) were calculated on untreated control plots of the cultivars Hidase and Shorima, respectively, compared with the maximum protected plots treated by Imidalm (Table 5).

Table 5.

Integrated influences of wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments on relative yield loss of wheat due to Fusarium head blight in the seven locations, southern Ethiopia, during the 2019 main cropping year.

| Treatment | Grain yield (t ha−1) | Relative yield (%) | Relative yield loss (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||

| Adiyo | 2.17 | 37.67 | -62.33 | |

| Bonke | 5.76 | 100.00 | 0.00 | |

| Chencha | 5.59 | 97.05 | -2.95 | |

| Gedeb | 3.64 | 63.19 | -36.81 | |

| Hulbareg | 2.40 | 41.67 | -58.33 | |

| North Ari | 0.94 | 16.32 | -83.68 | |

| Sodo Zuriya |

4.86 |

84.38 |

-15.63 |

|

| Wheat cultivar | Chemical seed fungicide | |||

| Hidase | Carboxin | 3.45 | 92.00 | -8.00 |

| Hidase | Thiram + Carbofuran | 3.70 | 98.67 | -1.33 |

| Hidase | Imidalm | 3.75 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| Hidase | Proceed Plus | 3.18 | 84.80 | -15.20 |

| Hidase | Thiram Granuflo | 3.51 | 93.60 | -6.40 |

| Hidase |

Untreated |

2.93 |

78.13 |

-21.87 |

| Shorima | Carboxin | 3.65 | 82.95 | -17.05 |

| Shorima | Thiram + Carbofuran | 4.05 | 92.05 | -7.95 |

| Shorima | Imidalm | 4.40 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| Shorima | Proceed Plus | 3.78 | 85.91 | -14.09 |

| Shorima | Thiram Granuflo | 3.70 | 84.09 | -15.91 |

| Shorima | Untreated | 3.38 | 76.82 | -23.18 |

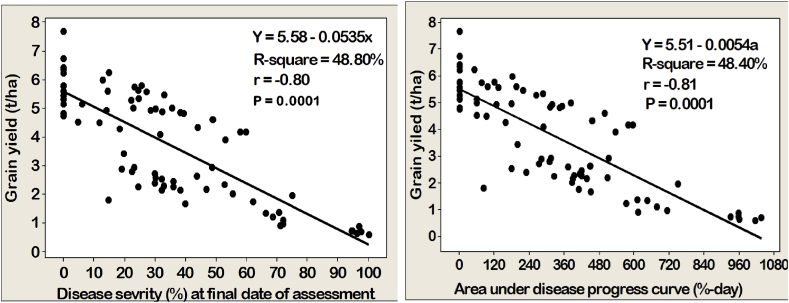

3.8. Association between fusarium head blight pressure with grain yield

Relationships and yield loss predictions between disease development (severity and AUDPC) and GY were examined using simple correlation and regression analysis, respectively. Variable levels of associations were observed between disease scores and GY (Figure 4). The association analysis results showed a highly strong negative correlation (r = - 0.80) and a highly significant (p < 0.0001) relationship between severity and GY. In addition, GY was highly significantly (p < 0.0001) and negatively associated (r = - 0.81) with AUDPC (Figure 4). Yield loss analysis in every portion of progression in disease development was observed using both final severity and AUDPC values with GY under plot-wise assessment. Analysis of linear regression revealed that there were significant (p < 0.0001) relations between final severity and GY and AUDPC and GY (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Estimation of relationships between losses in breed wheat grain yield and severity (left-hand) and area under disease progress curve (right-hand) of Fusarium head blight in the seven locations, southern Ethiopia, during the 2019 main cropping year.

The coefficient of determination (R-square) suggested that 48.80% of the disparities in yield loss have been elucidated by final severity than AUDPC (48.40%) during the growing period. That is, the contribution of FHB severity was more explanatory than the AUDPC in GY reduction. More importantly, the graph showed that for every single unit enhancement in disease severity, on that point about 0.0535-unit GY loss was resulted. However, the graph demonstrated that for every one-unit increase in FHB of AUDPC values, there was only a 0.0054-unit GY loss. As observed on the graph, the higher severity (at final date) and AUDPC suggested that the more vulnerability of wheat cultivars and the poor effectiveness of the treatment combinations against FHB, and consequently resulting in lower GY. This means the higher of disease severity and AUDPC value, the more vulnerable the wheat cultivars and the ineffectiveness of measures applied to manage FHB, which resulted in humble GY. The nearer the dot to the regression line suggests that the more powerful the connection between the final severity and AUDPC with GY, concerning GY loss. The minus sign in the regression equations (final severity and AUDPC) implied the inverse relationships of the final severity and AUDPC with the GY, which means the estimated degrees of the disease have a significant negative impact on the GY of wheat cultivars (Figure 4).

3.9. Cost-benefit analysis

For the integrated use of wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments for the FHB management, the NB and BCR were computed per location and treatment combinations. The cost-benefit analysis showed that significant variation in NB and BCR was observed among the evaluated experimental treatments in the seven locations (Table 6). Comparing the locations, the most prominent NB ($3415.55 and 3392.72 ha−1) and BCR (6.32 and 5.39) were computed at Bonke and Chencha, respectively. Conversely, the lowest NB ($145.28 and 462.68 ha−1) and BCR (0.35 and 0.87) were observed at North Ari and Adiyo, respectively. The NB inflicted from the marketing of goods for every one of chemical seed treatment wandered from $42055.60–67381.26 ha−1 on an untreated control plot of Hidase and Shorima treated with Imidalm, respectively. In addition, the BCR obtained from the selling of the grain for each chemical seed treatment ranged from 3.23 to 4.43 on Hidase treated with Carboxin and Shorima treated with Imidalm, respectively (Table 6). Cost-benefit analysis indicated that integration of Shorima with Imidalm exhibited the topmost NB ($67381.26 ha−1) and BCR (4.43), followed by the integration of Shorima with Thiram + Carbofuran correspondingly with the NB of $60837.76 ha−1 and BCR of 3.98. Overall, the planting of Shorima integrated with any chemical seed treatments, including the untreated plot, provides a better NB and BCR than Hidase in the same circumstances (Table 6).

Table 6.

Results of economic feasibility analysis for Fusarium head blight management through the integration of bread wheat cultivars and chemical seed treatments in the seven locations, southern Ethiopia, during the 2019 main cropping year.

| Treatment |

Grain yield (t ha−1) | Adjusted yield (t ha−1) 10% down | Total input cost ($ ha−1) | Gross benefit ($ ha−1) | Net benefit ($ ha−1) | Benefit-cost ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | |||||||

| Adiyo | 2.17 | 1.95 | 530.90 | 993.58 | 462.68 | 0.87 | |

| Bonke | 5.76 | 5.18 | 540.44 | 3955.99 | 3415.55 | 6.32 | |

| Chencha | 5.59 | 5.03 | 626.29 | 3999.21 | 3372.92 | 5.39 | |

| Gedeb | 3.64 | 3.28 | 422.79 | 1562.48 | 1139.69 | 2.70 | |

| Hulbareg | 2.40 | 2.16 | 518.18 | 1717.01 | 1198.83 | 2.31 | |

| North Ari | 0.94 | 0.85 | 419.61 | 564.90 | 145.28 | 0.35 | |

| Sodo Zuriya |

4.86 |

4.37 |

588.13 |

2781.56 |

2193.42 |

3.73 |

|

| Wheat cultivar | Chemical seed fungicide | ||||||

| Hidase | Carboxin | 3.45 | 3.11 | 15212.86 | 64865.58 | 49652.72 | 3.26 |

| Hidase | Thiram + Carbofuran | 3.70 | 3.33 | 15290.66 | 69454.14 | 54163.48 | 3.54 |

| Hidase | Imidalm | 3.75 | 3.38 | 15212.86 | 70497.00 | 55284.14 | 3.63 |

| Hidase | Proceed Plus | 3.18 | 2.86 | 15291.86 | 59651.31 | 44359.45 | 2.90 |

| Hidase | Thiram Granuflo | 3.51 | 3.16 | 15212.86 | 65908.44 | 50695.58 | 3.33 |

| Hidase |

Untreated |

2.93 |

2.64 |

13007.14 |

55062.74 |

42055.60 |

3.23 |

| Shorima | Carboxin | 3.65 | 3.29 | 15212.86 | 68619.86 | 53407.00 | 3.51 |

| Shorima | Thiram + Carbofuran | 4.05 | 3.65 | 15290.66 | 76128.42 | 60837.76 | 3.98 |

| Shorima | Imidalm | 4.40 | 3.96 | 15212.86 | 82594.12 | 67381.26 | 4.43 |

| Shorima | Proceed Plus | 3.78 | 3.40 | 15291.86 | 70914.14 | 55622.28 | 3.64 |

| Shorima | Thiram Granuflo | 3.70 | 3.33 | 15212.86 | 69454.14 | 54241.28 | 3.57 |

| Shorima | Untreated | 3.38 | 3.04 | 13007.14 | 63405.58 | 50398.44 | 3.87 |

Mean unit price of grain yield per ton was $663.18, the exchange rate of 1$ = Ethiopian Birr 31.45, at the time selling of harvested grain during the 2019 cropping years.

4. Discussion

The increase of the production areas under wheat cultivation led to the use of farm-saved seed and traditional ways of farming practices in Ethiopia as well as particularly in southern Ethiopia. The phenomenon (the use of farm-saved seed and traditional ways of farming practices) in the past four to five decades makes favorable environments for intensified infection of wheat with many fungal diseases that would adversely upset both quality and quantity of GY (Anteneh and Asrat 2020; Chernet and Mamaru 2020). As reported by CSA (2018), Anteneh and Asrat (2020), and Chernet and Mamaru (2020), a big proportion of the wheat production areas in Ethiopia as well as in the southern region are sown with farm-saved seed, seeds saved from the previous year of production. Recurrent use of farm-saved seed might lead to developing the inocula load of several diseases and dissemination of these diseases to where the diseases were not known before in the regions and Ethiopia as well.

Previous researchers suggested that host resistance combined with chemical seed treatment is considered a cost-effective and important approach to integrated FHB management (Gilbert and Haber 2013; Karasi et al., 2016; Shude et al., 2020). Accordingly, the integrated effects of host resistance and chemical seed treatment to FHB and yield performances of wheat were tested in open environments in seven locations of SNNPRs. The results of the present investigation showed that significantly different levels of variations were observed on all studies parameters under crosswise assessment. During the growing period, characteristic FHB symptoms were first observed on Hidase cultivar at ZGS of 58, which was on average at 22-days after anthesis, at North Ari, successor by Hulbareg, Adiyo, Sodo Zuriya, Gedeb, Chencha, and Bonke. The FHB symptoms characterized by the present study were analogous to the reports of McMullen et al. (2012), Mills et al. (2016), and Ghimire et al. (2020).

Integrated effects of wheat cultivar and chemical seed treatment significantly lowered the rates of disease progression, disease incidence, disease severity, and AUDPC in the study locations. In the present study, disparities in the rate of disease progression, incidence, severity, and AUDPC across the locations might have been due to host susceptibility, meteorological conditions (Figure 2), and the management approach followed. In addition, the earliness of the disease onset and the inocula load within the environment might be responsible for high disease pressure. Even if the weather conditions at Bonke and Chencha were conducive to FHB epidemic development, the disease pressure was lower compared with other locations, especially at North Ari. The phenomenon might be due to the humble amount of inoculant within the environs and the late occurrence of the disease in these locations. Moreover, crop rotation might be affected the FHB development at Bonke and Chencha than other locations. Faba bean was the precursor crop at Bonke and Chencha. At Gedeb, Adiyo, Hulbareg, North Ari, and Sodo Zuriya, the precursor crops planted plus environmental conditions might also significantly help higher disease development in these locations. Barley for the former one location and wheat for the later five locations were precursor crops.

Earlier researchers reported that the disparities in conducive weather demand in association with genetic and ecological adaptations within Fusarium species complex, especially Fusarium graminearum, can cause disease in a diversity of environmental circumstances, which resulting in the widespread distribution of FHB worldwide (Parry et al., 1995; Lenc 2015). Van der Plank (1963) and Campbell and Madden (1990) reported the magnitude of disease pressure is impacted by the environment, host susceptibility, pathogen aggressiveness, and inoculum production by infected individuals. The authors also suggested that the probability of inoculum reaching and contact with a disease-free host, time for a newly infected individual to produce an inoculum, and the availability, viability, and dispersibility of infective propagules are main factors in the course of epidemic development. Moreover, Hoover (2011), Gilbert and Haber (2013), Karasi et al. (2016), and Shude et al. (2020) reported that FHB development significantly reduced by crop rotation, especially crop rotation with none Poaceae family crops during the growing season.

On the other hand, significant variations between and among the treatment combinations were observed for rates of disease progression, incidence, severity, and AUDPC. Reduced rates of disease progression and subsequent lowered FHB epidemic development in the present study could be due to the chemical seed treatment along with the cultivars’ genetic background. This was explained by inhibition of injury progression, infectious inocula production, and the establishment of an additional infection within and outside the field due to retardation of the germination and development of the pathogen. The low and high effectiveness in reducing FHB intensity might also have been related to the mode of actions, ability of the chemical seed treatments, and resistance of the pathogens along with the genetic makeup of the cultivars. These findings were consistent with the work of Green et al. (1990) and Getachew et al. (2021) who mentioned that mode of action and active ingredients constituted in the agrochemical product preparation had significant effects on the ability to reduce disease pressure and resistance of the pathogens. Overall, FHB pressure was comparatively higher in plots of Hidase cultivar under any combination with chemical seed treatments than Shorima cultivar. Thus, chemical seed treatments, including Imidalm and Thiram + Carbofuran, showed effectiveness against FHB with consistent results on both Hidase and Shorima cultivars. So, the outcomes of the present study as exhibited variation in FHB development was due to the level of cultivar resistance, chemical seed treatments used, and environmental conditions. The mean highest FHB pressure was observed from the untreated control plot of the Hidase cultivar than treated and untreated control plots of the Shorima cultivar. This approach, integration of chemical seed treatments and host resistance, possibly will help to utilize the integration capabilities of each management tactic to manage FHB in the investigational areas of SNNPRs and elsewhere having analogous agro-ecologies.

In this regard, Wegulo et al. (2011), DeVuyst et al. (2014), Lingenfelser et al. (2016), and Pinto et al. (2019) reported that if cultivar resistance combined with chemical seed treatment applied for FHB management, the disease pressure had reduced under a given combination of chemical seed treatment and cultivar resistance than the untreated control plots. In the present study, the different chemical seed treatments had responded to various levels of disease intensity, and this might have also resulted from the difference in the active substances constituted in the product formulation of the fungicides. Homdork et al. (2000), Sawinska and Malecka (2007), and Turkington et al. (2016) reported that variation in the fungicidal activity of a different seed treatment had differences in the capability of the fungicide to retard the epidemic development of FHB, which was elucidated by the confrontation of the pathogen through overpowering the chemical product active ingredients. The findings of this study confirmed the wheat cultivars differed in the genetic potential to FHB supplemented with chemical seed treatments exhibited lower FHB epidemics. Thus, from the results of different chemical seed treatments in combination with wheat cultivars would be possible to deduce that planting of Shorima in combination with either Imidalm or Thiram + Carbofuran could effectively reduce the magnitude of FHB pressure during the epidemic periods.

Analysis of variance also revealed a considerable treatment variation was observed for TSW and GY in the seven locations. The difference in TSW and GY in the seven locations might have turned out from the disparity in the weather conditions, the actions of experimental treatment, and the extent of disease pressure in the study locations. About 83.68% GY gap was perceived between GY harvested at Bonke and North Ari. Campbell and Madden (1990), Agrios (2005), Gaspar et al. (2014), and Turkington et al. (2016) confirmed the existence of a favorable pathosystem among the studied environments significantly favors the epidemic development of the pathogen. Consequently, the pathogen affected the metabolic process of the crop and reduced the phenology, growth and development, and yield-associated traits of the genotype, and vice versa. In terms of treatment combinations for TSW and GY, the top-performing experimental treatments were Shorima cultivar integrated with Imidalm, followed by Shorima cultivar integrated with Thiram + Carbofuran fungicides.

From the results obtained, the highest TSW and GY were observed on Shorima than Hidase under all circumstances, in both untreated and treated with chemical seed treatments. The chemical seed treatments, including Imidalm and Thiram + Carbofuran, showed consistent results on GY obtained in both Hidase and Shorima cultivars. From the results obtained, it is conceivable to understand that integrated application of cultivar resistance and chemical seed treatment had a vital role in enhancing GY, which may perhaps be ascribed to their favorable influences on GY imparting traits while creating negative influences for various metabolic actions of the pathogen. According to May et al. (2010) and Gaspar et al. (2014) reports, combined use of cultivar resistance and chemical seed treatments along with good cultural practices had a favorable effect on the GY of the crops. Other related reports demonstrated that combined approaches of cultivar resistance and chemical seed treatments significantly minimized disease pressure and amplified GY over the untreated control plots (Schaafsma and Tamburic-Ilincic, 2005; Turkington et al., 2016).

Response of cultivar and chemical seed treatments, and subsequent variation in FHB pressure due to integration of them could be responsible for comparative yield advantages and relative yield losses, which were obtained per location and treatment combination, along with other factors. Under crosswise assessment, GY losses varied among locations experimented with the integration of wheat cultivars and seed treatment fungicides. The highest GY losses were computed at North Ari and Adiyo, respectively, compared with the maximum GY obtained from Bonke. The likely reasons could be due to the environmental conditions that favor the highest FHB development and other factors, including other wheat diseases that causes high GY losses. Across the locations, GY losses differed among the evaluated experimental treatments on each plot. The highest GY losses were calculated for untreated control of the cultivars Hidase and Shorima, respectively, related to the maximum protected plots. The highest GY losses might have resulted from the severe FHB pressure on the head, which was resulted in shriveled, pre-mature, shrunken, and sometimes causes dissertations of grain, and the GY become uneconomical due to losses in grain quality and quantity. Windels (2000), Pirgozliev et al. (2003), Gilbert and Haber (2013), and Shude et al. (2020) reported that 100% GY loss had been noticed on the severely affected field due to FHB on wheat crops.

Highly significant relationships were observed between epidemiological parameters and GY. The correlation analysis showed that disease severity and AUDPC maintained a negative and significantly correlated with GY. The negative association between epidemiological parameters and GY indicates the observed levels of disease severity, and AUDPC exhibited a substantial negative effect on the GY of wheat. Guant (1995), Campbell and Madden (1990), and Agrios (2005) mentioned epidemiological variables had been strongly correlated with the host growth and development, which is explained by the deterioration of physiological processes of the host by the pathogen, and consequently, retards the phenology, growth and development, and yield-associated characters of the crop. To perform a linear regression analysis, the relationship of epidemiological parameters and GY was accomplished in plot-wise assessment. The regression analysis showed that significant yield loss predictions in every unit of disease progression were observed between the epidemiological parameters and GY. The higher the disease severity and AUDPC in FHB epidemic development, the less the effect of the management options applied, treated, and untreated control plots of the two wheat cultivars under combinations. Thus, as disease severity and AUDPC increase, the yield declines and shifts in the direction of zero asymptotes, which suggests the inverse association between epidemiological parameters and GY. Wheeler (1969), Guant (1995), Campbell and Madden (1990), and Agrios (2005) suggested that there had been a potent relationship between plant diseases and yield traits of the crop.

A cost-benefit analysis has been calculated for each experimental treatment to determine the profitability of FHB management through the integration of wheat cultivar and chemical seed treatment. Bonke and Chencha incurred the highest NB and BCR, while the lowest NB and BCR were computed from North Ari and Adiyo. Variation in NB and BCR might have been affected not only by disease pressure, management options followed, and environmental factors but also the variability in the total input costs of production in the locality. Previous scholars reported that the positive economic feasibility benefits incurred from a given agricultural commodity production had strongly affected by several factors, which includes the total input expenses of production, time of crop produced (main or off-season), the total amount of yield obtained, place of merchandise (local market or capital city) and product selling price at the time of marketing (Cook and King 1984; CIMMYT 1988). Likewise, variation in NB and BCR was seen among the tested treatment combinations. The cost-benefit analysis also revealed that the uses of Shorima treated with Imidalm incurred the highest NB and BCR, successor by Shorima treated with Thiram + Carbofuran over the other experimental treatments. The highest NB and BCR obtained from the planting of wheat with chemical seed treatment complementation might be attributed to high GY. While the lowest net benefit and benefit-cost ratio were ascribed to the minimum GY obtained due to high FHB pressures and other factors. Thus, it was evident that the uses of Shorima in combination with Imidalm or Thiram + Carbofuran were effective since they showed the most profitable over the other treatments and could be suggested for the producers. Cook and King (1984) and Foster et al. (2017) reported that better economic benefit due to additional cost of production was observed on the use of fungicide lonely or in combination with other disease management approaches for major diseases of wheat under field conditions.

5. Conclusions

During the study, untreated control plots were severely deteriorated by the FHB press, especially at North Ari. At Bonke and Chencha, the lower FHB pressure and higher yield attributes were observed compared with other locations. The empirical evidence of the current study discovered that the practicing of cultivar resistance complemented with chemical seed treatment exhibited a noticeable effect in reducing FHB epidemics and in enhancing the yield and yield characters of wheat in all locations. In addition, the cost-benefit analysis showed that integrated practicing of cultivar resistance and chemical seed treatment gave the highest NB and BCR in both crosswise and experimental treatment evaluations. The exploitation of moderately resistant (Shorima) in combination with Imidalm or Thiram + Carbofuran was verified to be the most profitable tactic in decreasing FHB incidence, severity, and AUDPC apart from enhancing wheat production and productivity in the study locations. The results acquired from the present study confirmed that the genetic potential of cultivar was supplemented by chemical seed treatment helped in lowering FHB pressure and maximizing GY and gave the most eminent monetary reward. Overall, the applying of the cultivar Shorima in a combination of either Imidalm or Thiram + Carbofuran as integrated management manner was found to be a profitable approach. These combinations could be suggested to the farmers in investigational areas of SNNPRs and elsewhere having analogous agro-ecologies to manage FHB and sustain wheat production and productivity. However, the sole use of chemical seed treatment does not as effective as post-anthesis aerial application of fungicide up to maturity of the crop. Hence, aerial application of fungicide in combination with moderately resistant and/or susceptible cultivar supplemented by either Imidalm or Thiram + Carbofuran chemical seed treatment at an early stage should be considered during post-anthesis of the crop to get better control of the disease up to maturity. In the present study, mycotoxin production and contaminations in association to yield quality losses and quantification was not analyzed. Thus, a further study aiming at mycotoxin production and contaminations must be analyzed in connection with its effects on yield quality losses and quantification for more efficient and trustworthy management schemes development for FHB in the study locations.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Getachew Gudero Mengesha: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Shiferaw Mekonnen Abebe: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Abate G/Mikael Esho; Asaminew Amare Mekonnen; Zerhun Tomas Lera; Kedir Bamud Fedilu; Yosef Berihun Tadesse; Yisahak Tsegaye Tsakamo; Bilal Temmam Issa; Dizgo Chencha Cheleko: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Misgana Mitku Shertore; Agdew Bekele W/Silassie: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Southern Agricultural Research Institute, Southern Nations, Nationality and Peoples’ Region.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The profound appreciations go to the Crop Research Work Process staff and the car drivers of all respective research centers, including Arba Minch, Areka, Bonga, Hawassa, Jinka, and Worabe, under SARI for their supports in one or other ways during the study period. The authors also would like to say warm acknowledgment to Kulumsa Agricultural Research Center (EIAR) staff of the wheat breeding program for providing the seeds. Deepest thanks also go to farmers, development agents, and extension workers of the respective Bureau of Agricultural Office at each study district for their willingness and collaboration during the study. Finally, special appreciation goes to Tahir Hajdi Mohammed (MSc) for his willingness to draw the map of the experimental locations.

References