Abstract

Soil acidity is the major soil chemical constraint that limits agricultural productivity in the highlands of Ethiopia receiving high rainfall. This study was conducted to evaluate the effect of different lime rates determined through different lime rate determination methods on selected soil chemical properties and yield of maize (Zea mays L.) on acidic Nitisols of Mecha district, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. The experiment had 10 treatments (0, 0.06, 0.12, 0.18, 1, 2, 3.5, 4, 7 and 14 tons ha−1 lime) that were calculated by three lime rate determination methods and applied through three lime application methods (spot, drill and broadcast). The experiment was arranged in randomized complete block design (RCBD) with four replications. N at the rate of 180 kg ha−1 and P at the rate of138 P2O5 kg ha−1 were applied to all plots. A full dose of P and lime as a treatment were applied at planting; whereas N was applied in split, 1/2 at planting and 1/2 at knee height stage. One composite soil sample before planting from experimental site and again one composite sample from each experimental unit were taken after harvest to analyze soil chemical parameters following appropriate laboratory procedure. Liming showed a positive significant difference on pH-H2O, pH-buffer, cation exchange capacity (CEC) and exchangeable bases but it had an inverse and significant effect on exchangeable acidity (EA). However, it didn't show any significant difference on soil C and N. Grain and above-ground biomass of maize yields had significant differences among treatments. The highest grain and biomass yields (7719 and 18180.6 kg ha−1, respectively) were obtained from application of broad cast method while the lowest (6479 and 15004.6 kg ha−1, respectively) were obtained from control treatment. Drill lime application method provided better efficiency with over 200% cost reduction advantage compared to the broadcast method to ameliorate the same level of acidity. Application of 3.5 tons ha−1 lime in the drilling method is recommendable to ameliorate soil acidity. However, from an economic point of view, application of 0.12 tons ha−1 lime applied in the micro-dosing method is more profitable due to low variable cost.

Keywords: Exchange acidity, Lime, Maize, pH-buffer, pH-water

Exchange acidity; Lime; Maize; pH-buffer; pH-water.

1. Introduction

Agriculture in Ethiopia has long been a priority and focus of national policy, such as Agricultural Development Led Industrialization (ADLI) and various large-scale programs, like Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP). Close to 10% of the country's land area is currently under crop cultivation and the sector employs more than 85% of the population, generates over 46% of GDP and 80% of export earnings and has a significant role to play in improving food security (Alemayehu, 2008). Soil is a medium for plant growth. It provides nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sulfur and many other trace elements that support biomass production. It also used as water holding tank for preserving moisture. Some of the soil properties like texture, aggregate size, porosity, aeration (permeability) and water holding capacity affecting plant growth (FAO and ITPS, 2015).

Maize is one of the three most important cereals with wheat and rice for food security at the global level and very important for the diets of Africa and Latin America (Bekele et al., 2011; FAOSTAT, 2010). In many developed countries and the emerging economies of Asia and Latin America, maize is increasingly being used as an essential ingredient in the formulation of livestock feed (Bekele et al., 2011). In Ethiopia, maize is the most widely cultivated cereal crop with 16% area coverage, 26% production potential and 6.5 million tons of production (CSA, 2014). Estimated average yields of maize for smallholder farmers in Ethiopia is about 3.2 tons ha−1 (CSA, 2014; Tsedeke et al., 2015), which is much lower than the yield recorded under experimental plots of 5–6 tons ha−1 (Dagne et al., 2008). To solve soil fertility problems and maximizing maize yield, different research have been undertaken in Ethiopia using various fertilizer sources (Birhan et al., 2017).

Acid soils are toxic for plants as a result of nutritional disorders, unavailability of essential nutrients such as Ca, Mg, P and Mo and toxicity of Al, Mn and H activity (Jayasundara et al., 1998). In acid soils, excess Al primarily injures the root apex and inhibits root elongation. This poor root growth again leads to reduced water and nutrient uptake and consequently crops grown on acid soils face poor nutrients and water availability with the net effect of reducing growth and yield of crops (Wassie and Shiferaw, 2014). Occurrences of an increasing trend of soil acidity in arable land is attributed due to the high amount of rainfall, intensive cultivation and continuous use of acid-forming inorganic fertilizers (Abdenna et al., 2007). As Taye (2007) reported, soil acidity in Ethiopia is expanding both in scope and magnitude and becoming severely limiting crop production.

To solve such problems, proper application of lime is the fundamental action. Adane (2014) reported that soil pH enhanced from 5.03 to 6.72 by applying 3.75 tons ha−1 lime. Based on this author, CEC and available P of the soil also increased in a similar way. Inversely, EA and most availability of micronutrients like Bo, Cu, Fe, Mn and Zn significantly decreased due to liming (Goedert et al., 1997; Kebede and Dereje, 2017). Therefore, the interest of this study was to investigate the effect of different lime application methods determined through different rate determination methods on the selected soil chemical properties and maize (Zea mays L.) yield and yield components.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

The study was conducted at Mecha district, Kudemie kebele (lowest administrative unit of Ethiopia), which is approximately 525 km north of Addiss Ababa. Specifically, it is located at 11° 23′ 33.49″ Northing and 37° 06′ 25.23″ Easting at altitude of 1972 m above sea level (m.a.s.l) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area.

70% of the study district is level topographic feature. From the total area of the district, 13% is undulated and the remaining 8% and 4% of the area are covered by mountainous and valley topographies, respectively. The annual mean rainfall amount of the district is 1572 mm and the mean temperature is 25 °C. According to Ethiopian traditional agro-ecological classification, the study district is classified under Weyina Dega (mid altitude, 1800–2400 m.a.s.l) (Mekonnen, 2015). Specifically, the mean annual rainfall and temperature of the experimental site during the cropping season were 314.9 mm and 19.3 °C, respectively (Koga irrigation metrological station, 2018) (Figure 2). From the total area coverage of the district, 4% of the area (5,927 ha) is addressed by Koga irrigation command area (Eyasu, 2016).

Figure 2.

Rainfall and temperature data during the cropping year at experimental site.

The dominant farming system of the district is mixed farming system that is livestock with crop production. The average productivity of the district has been substantial due to the challenges of low soil fertility, land shortage, and crop pest and disease damage. All systems of production including ploughing, harvesting and threshing are done by human and animal powers. The major crops grown in the district are maize, finger millet, tef and Niger seed on Nitisols and tef, Niger seed, chickpea and grass pea on Vertisols under rain feed conditions. Vegetables like cabbage, potato and sugar cane are also grown under irrigation (Mekonnen, 2015).

2.2. Experimental methods

The experiment was conducted in 2018 cropping season laid in randomized complete block design (RCBD) having 4 replications. The space between rows, plants, plots, and blocks was 0.75, 0.3, 1 and 1.5 m, respectively. Each plot had a 3.75 X 3 m gross size and 5.4 m2 net plot size. A full dose of P fertilizer and all lime rates were applied at planting; whereas, N fertilizer was applied in split, 1/2 at planting and 1/2 at knee height stage. The levels of N and P2O5 were 180 and 138 kg ha−1, respectively (Adet Agricultural Research Center, 2002, unpublished). The amount of lime added and ways of application was based on treatment setup indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Treatment setup of the conducted experiment.

| No. | Treatments | Application methods |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control | Treatment without lime |

| 2 | 0.06 ton ha−1 | Micro-dosing in spot near the seed hill |

| 3 | 0.12 ton ha−1 | Micro-dosing in spot near the seed hill |

| 4 | 0.18 ton ha−1 | Micro-dosing in spot near the seed hill |

| 5 | 1 ton ha−1 | ¼ FDEA = in drilling along the rows |

| 6 | 2 ton ha−1 | ½ FDEA = in broadcasting |

| 7 | 3.5 ton ha−1 | ¼ FDB = in drilling along the rows |

| 8 | 4 ton ha−1 | FDEA = in broadcasting |

| 9 | 7 ton ha−1 | ½ FDB = in broadcasting |

| 10 | 14 ton ha−1 | FDB = in broadcasting |

Note: FDEA = Full dose based on exchangeable acidity lime recommendation; FDB = Full dose based on pH- buffer lime recommendation.

Weeding and other necessary agronomic practices were implemented mechanically. Agro-lambarcin chemical was used at vegetative stage to control the American boll worm. The test crop was improved maize variety, BH-540. The blended fertilizer NPSB was used as a source of both P and N nutrients. While Urea fertilizer was used as a source of sole N nutrient. Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) was used for lime source. Average purity and finesse of lime used were 92% and 0.045mm, respectively.

2.3. Lime rate determination

The amount of lime rates used was determined through 3 mechanisms. The first 4 rates (0, 0.06, 0.12 and 0.18 tons ha−1) were added directly as micro-dosing levels. The other 3 rates (1, 2 and 4 tons ha−1) were calculated based on EA method which as indicated in Eq. (1) (Birhanu et al., 2016) and the remaining 3 rates (3.5, 7 and 14 tons ha−1) were calculated based on SMP-pH-buffer to attain target pH value of 6.5 from the initial result as stated by Van Reeuwijk (1992).

| (1) |

where: EA = 2.54 cmol kg−1, Bulk density = 1.41 Mg m−3 taken from pre-liming soil analysis result.

2.4. Soil sampling, preparation and analysis

One composite soil sample before planting from five points in crisscross sampling technique and from each experimental plot after harvesting using the previous technique was taken at the depth of 0–15 cm. Soil texture, pH-H2O, pH-buffer, EA, CEC, OC, AP, TN, and all exchangeable cations were analyzed. The parameters were analyzed at Adet Agricultural Research Center's soil laboratory. From this, soil pH-H2O was determined in soil-water suspensions of 1:2.5 ratios. AP was analyzed through Olsen method (Olsen et al., 1954); while TN was analyzed following the Kjeldahl method (Bremner and Mulvaney, 1982). Soil organic carbon content was determined by wet digestion method using the Walkley and Black procedure (Nelson and Sommers, 1982). CEC and base cations of the soil were determined using ammonium acetate (CH3COONH4) extraction method by taking 5g of sampled soil (Sahlemedihin and Taye, 2000). Based on the above soil parameters, base saturation (BS) and acid saturation (AS) percentage values were also calculated through the formulas stated below (Eq. (2)).

| (2) |

2.5. Data collection and analysis

Agronomic data like plant height, ear length, ear diameter, harvest index (HI) and all biological yields (grain + above ground biomass) were collected. SAS software version 9.0 was used to analyze all collected agronomic data (SAS Institute, 2002). LSD was used for mean separation comparison. The economic analysis was done following the methodology of CIMMYT (1988).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of lime on selected soil chemical properties

3.1.1. Soil pH-H2O and pH-buffer

Based on pre-planting soil analysis result, the soil on the study area was sandy clay loam with the percentage of 32% clay, 11% silt, and 57% sand (using textural triangle classification principle) (Table 2). Soil pH-H2O changed from 4.85 (very strongly acidic) to 6.21 (slightly acidic) (Murphy, 1968; Tekalign, 1991) through the application of 3.5 tons ha−1 lime using drill application method. This pH value is regarded to be suitable for maize production (Ndubuisi and Deborah, 2010). However, the minimum value (4.87) was recorded from treatment 2 which received 0.06 tons ha−1 lime through spot application method. Comparing the three lime application methods, maximum pH-H2O values were obtained from the drilling method. In general, pH-H2O of the soil in the study site showed a significant difference (p < 0.001) among treatments. This result agreed with Achalu et al. (2012) and Getachew et al. (2017) who stated that soil pH sharply increased by liming. Like that of pH-H2O, pH-buffer had a significant difference (p < 0.001) among treatments. Similarly, minimum and maximum pH-buffer values were observed on points where the minimum and maximum pH-H2O values were recorded in magnitudes of 4.98 and 6.03, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Soil pH-H2O, pH-buffer, OC, CEC, AP and EA values for post-harvested soil samples.

| Treatments | Parameters |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (H2O) | pH (buffer) | OC (%) | TN (%) | CEC (cmol kg−1) | AP (mg kg−1) | EA (cmol kg−1) | |

| Initial values | 4.85 | 5.24 | 2.19 | 0.17 | 19.95 | 18.03 | 2.54 |

| Control (no lime) | 5.11de | 5.14de | 1.94 | 0.166 | 22.81ab | 17.17d | 1.939a |

| 0.060 ton ha−1 | 4.87e | 4.98e | 2.01 | 0.149 | 22.89ab | 37.80a | 2.020a |

| 0.120 ton ha−1 | 4.95e | 5.01e | 2.07 | 0.168 | 21.85b | 33.56b | 1.788a |

| 0.180 ton ha−1 | 5.27de | 5.07de | 1.95 | 0.168 | 23.47ab | 34.47ab | 0.936b |

| 1 ton ha−1 | 5.52cd | 5.75ab | 1.89 | 0.139 | 24.53ab | 31.86bc | 0.480bc |

| 2 ton ha−1 | 5.28de | 5.33dc | 2.09 | 0.161 | 24.82ab | 29.12c | 0.460bc |

| 3.5 ton ha−1 | 6.21a | 6.03a | 1.95 | 0.162 | 25.41a | 31.34bc | 0.070c |

| 4 ton ha−1 | 5.49cd | 5.65b | 2.09 | 0.144 | 23.38ab | 20.01d | 0.116c |

| 7 ton ha−1 | 5.77bc | 5.55bc | 2.00 | 0.163 | 23.22ab | 18.93d | 0.288c |

| 14 ton ha−1 | 6.17ab | 6.01a | 1.95 | 0.142 | 24.50ab | 20.90d | 0.048c |

| Mean | 5.46 | 5.45 | 1.99 | 0.156 | 23.69 | 27.52 | .814 |

| P | ∗∗ | ∗∗ | Ns | Ns | ∗ | ∗∗ | ∗∗ |

| CV (%) | 5.55 | 3.97 | 10.49 | 15.05 | 10.24 | 10.53 | 50.31 |

| Texture – clay (32%) + silt (11%) + sand (57%) = sandy clay loam | |||||||

Note: ∗ = significant, ∗∗ = highly significant, CV = Coefficient of variation. Means followed by the same letter in a column are not significantly different at p < 0.05.

3.1.2. Soil organic carbon and total nitrogen

Based on nutrient rating level of Tekalign (1991), both pre-planting and post-harvest soil sample organic carbon (OC) and total nitrogen (TN) values were grouped under medium levels (Table 2). However, based on Murphy (1968) and Ethiosis (2016), the recorded TN values could be grouped in medium to high (0.10–0.15%) and low to optimum (0.15–0.3%), respectively.

As reported by several authors (Kebede and Dereje, 2017; Jafer and Gebresilassie, 2017; Mesfin et al., 2014), OC and TN didn't show any significant difference among treatments through the application of different lime rates using different application methods (Table 2).

3.1.3. Cation exchange capacity

Based on the analysis of variance (ANOVA), soil cation exchange capacity (CEC) values showed significant difference (p < 0.05) among treatments. Treatment 3 and 7 which received 0.12 and 3.5 tons ha−1 lime and applied in spot and drilling application methods, respectively gave the minimum and maximum values with the magnitudes of 21.85 and 25.41 cmol kg−1, respectively. Achalu et al. (2012) and Adane (2014) stated that numerically the mean values of CEC showed increments with the increase in applied lime rates. Based on Landon (1991) and Hazelton and Murphy (2007) ratings, all recorded CEC values of soil samples collected before lime application and at post-harvest were grouped under moderate ranges (Table 2).

3.1.4. Available phosphorus

As shown in Table 2, available phosphorus (AP) values among the treatments showed significant difference (p < 0.001) due to different amounts of lime application through different application methods. The minimum and maximum values were observed on the control treatment (17.17 mg kg−1) and micro-dosing of 0.06 tons ha−1 lime (37.80 mg kg−1). In this study, AP showed a decreasing trend with an increasing amount of lime applied, which is contrary to the findings reported by several authors (Adane, 2014; Dessalegn et al., 2017; Getachew et al., 2017; Kebede and Dereje, 2017). This could be due to the fact that the available P concentrations were above the critical level (11.6 mg kg−1) stated by Yihenew et al. (2003). However, this result agreed with the findings of Haynes (1982) who reported that at high soil pH and low Al3+ concentration values, the precipitation of insoluble calcium phosphates has the power to reduce P availability. Since the amounts of exchangeable Al are trace in the soils, fixation of free AP could be caused by Ca when a high amount of lime is applied.

3.1.5. Exchangeable acidity

Exchangeable acidity (EA) showed a highly significant (p < 0.01) difference among treatments (Table 2). The minimum and maximum EA values were recorded from treatments that received 14 tons ha−1 lime (applied in broadcasting) and 0.06 tons ha−1 lime (applied in spot) with magnitudes of 0.048 and 2.020 cmolkg-1 of soil, respectively. However, the exchangeable Al3+ for all samples was in a trace amount in the study area which suggested that the source of soil acidity was H+. Exchangeable acidity (EA) showed a decreasing trend with increase in the amount of lime applied which agreed with findings of Achalu et al. (2012); Adane (2014); Dessalegn et al. (2017) and Getachew et al. (2017).

3.1.6. Exchangeable bases

As shown in Table 3, exchangeable Ca and Mg showed highly significant (p < 0.01) whereas, exchangeable K and Na showed significant difference among treatments (p < 0.05) due to liming. All minimum and maximum exchangeable base values were recorded on treatments that received 0.06 and 3.5 tons ha−1 lime through spot and drill lime application methods, respectively in exception of maximum exchangeable Mg. This showed that drill lime application is more efficient for the amendment of the basic cations in acidic soils than the broadcast application methods that agreed with the finding of Birhanu et al. (2016).

Table 3.

The effect of lime rates on soil exchangeable bases, BS and AS.

| Treatment | Parameters |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | K | Na | BS (%) | AS (%) | |

| Initial values | 9.8 | 2.68 | 1.14 | 0.31 | 69.83 | 12.13 |

| Control (no lime) | 10.73de | 2.90bc | 1.38dc | 0.48bc | 69.03ab | 8.69a |

| 0.060 ton ha−1 | 10.18e | 2.30c | 1.20d | 0.44c | 62.06b | 8.80a |

| 0.120 ton ha−1 | 10.85cde | 2.68bc | 1.43bcd | 0.45c | 71.61ab | 8.01a |

| 0.180 ton ha−1 | 11.38bcd | 3.03b | 1.48abc | 0.44c | 70.43ab | 3.81b |

| 1 ton ha−1 | 12.30ab | 3.05b | 1.63ab | 0.61ab | 72.37ab | 1.92bc |

| 2 ton ha−1 | 11.85abcd | 3.05b | 1.53abc | 0.58abc | 68.69ab | 1.84bc |

| 3.5 ton ha−1 | 12.95a | 3.98a | 1.70a | 0.65a | 75.85ab | 0.27c |

| 4 ton ha−1 | 11.75bcd | 3.15b | 1.42bcd | 0.56abc | 74.64ab | 0.49c |

| 7 ton ha−1 | 12.03abc | 3.88a | 1.52abc | 0.47bc | 78.71a | 1.25c |

| 14 ton ha−1 | 12.50ab | 4.30a | 1.52abc | 0.64a | 78.19a | 0.19c |

| Mean | 11.65 | 3.23 | 1.48 | 0.53 | 72.16 | 3.53 |

| P | ∗∗ | ∗∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗∗ |

| CV (%) | 7.02 | 14.13 | 10.96 | 19.29 | 13.58 | 46.65 |

Note: ∗ = significant, ∗∗ = highly significant, CV = Coefficient of variation. Means followed by the same letter in a column are not significantly different at p < 0.05.

Based on FAO (2006) nutrient rating, recorded exchangeable Ca, Mg, K, and Na grouped under high, medium to high, high to very high, and medium levels, respectively. It is apparent that, lime application increases exchangeable bases which is supported by findings of Hirpa et al. (2013); Holland et al. (2017); Jafer and Gebresilassie (2017) and Getachew et al. (2017). These authors stated that treating acid soils with lime increases exchangeable bases and decrease some micronutrients (Fe, Zn) in the soil.

3.1.7. Base and acid saturation percentages

Base saturation percentage showed significant difference (p < 0.05) and the values increased with increased lime rate. Based on Hazelton and Murphy (2007), all the observed base saturation percentage values can be grouped at a high rating level (60–80%). Acid saturation percentage showed a decreasing trend with increasing lime rate which is in agreement with findings of Achalu et al. (2012); Adane (2014) and Getachew et al. (2017) (Table 3). Acid saturation percentage reduced from 8.69% (in the 0 ton ha−1) to 0.19% at 14 tons ha−1 lime application rates.

3.2. Recommended lime (LR) equations based on soil acidity indices

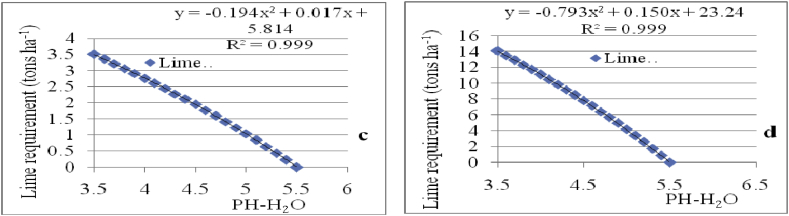

Lime requirement (LR) decreased when soil pH-buffer and pH-H2O increased for both drilling and broadcast lime application methods (Figures 3 and 4). However, LR increases when EA of soil increased for the same methods of lime application (Figure 5) which agreed with the findings of Shoemaker et al. (1961) and Van Reeuwijk (1992).

Figure 3.

LR equations for drill (a) and broadcast (b) application methods determined using pH-buffer index.

Figure 4.

LR equations for drill (c) and broadcast (d) application methods determined using pH-H2O index.

Figure 5.

LR equations for drill (e) and broadcast (f) application methods determined using EA index.

Based on the deriving equations indicated in Table 4, calculated lime rate based on pH-buffer, pH-H2O and EA ranged from 0.13-2.34, 0.22–3.50 and 0.11–2.07 tons ha−1 for drilling method and 1.18–20.83, 0.90–14.11 and 0.53–7.86 tons ha−1 for the broadcast method, respectively. Based on these readings, amount of lime required through drilling is much lower than the broadcast application method to ameliorate the some level of acidity for the same soil acidity index which agreed with finding reported by Birhanu et al. (2016).

Table 4.

LR equations developed from soil acidity indices.

| Application methods | Acidity index | Index unit | LR equations | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broadcast | pH- buffer | - | Y = -1.0063x2 + 3.383x + 25.845 | 0.9998 |

| pH-H2O | - | Y = -0.7935x2 + 0.151x + 23.249 | 0.9999 | |

| EA | Cmol+ kg−1 | Y = 1.5051x2 + 1.3794x + 0.1728 | 0.9946 | |

| Drilling | pH- buffer | - | Y = -0.1106x2 + 0.353x + 2.9735 | 0.9998 |

| pH-H2O | - | Y = -0.1947x2 + 0.017x + 5.8147 | 0.9999 | |

| EA | Cmol+kg−1 | Y = 0.2681x2 + 0.280x + 0.0497 | 0.9939 |

NB: Y= Lime rate to be applied; X = Soil acidity index value.

3.3. Effect of lime on yield and yield components of maize

As shown in Table 5, the applied lime didn't show any significant difference in maize plant height, ear length, ear diameter, thousand seed weight and harvest index among treatments. Although the experiment didn't show any significant difference in the above-listed yield components, the maximum values of each yield component were recorded on treatments that received highest amount of lime which is supported by Gitari et al. (2015) and Opala (2017). Regardless of this, maize grain and above-ground biomass yields showed significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) among treatments. Generally, both grain and above-ground biomass yields in the experiment showed an increasing trend with increasing lime rate which is supported by findings of Komljenovic et al. (2015) and Oloo (2016).

Table 5.

Plant height, ear length, ear diameter, harvest index, thousand seed weight, grain and above-ground biomass yields.

| Treatment | PH (cm) | EL (cm) | EDI (cm) | HI (%) | TSW (g) | GY (kg ha−1) | AGBM (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (no lime) | 201.05 | 15.40 | 4.54 | 37.87 | 397.75 | 6479.1b | 15004.6b |

| 0.060 ton ha−1 | 202.00 | 15.48 | 4.63 | 38.44 | 399.75 | 6628.3b | 15721.8ab |

| 0.120 ton ha−1 | 200.15 | 16.35 | 4.61 | 38.91 | 400.75 | 6840.3ab | 15972.2ab |

| 0.180 ton ha−1 | 200.00 | 16.03 | 4.66 | 39.84 | 401.50 | 6621.8b | 15930.6ab |

| 1 ton ha−1 | 201.00 | 16.60 | 4.73 | 40.22 | 407.00 | 6862.4ab | 16333.3ab |

| 2 ton ha−1 | 201.80 | 16.65 | 4.63 | 39.86 | 406.50 | 6871.4ab | 16620.4ab |

| 3.5 ton ha−1 | 202.60 | 16.40 | 4.65 | 39.83 | 405.25 | 6964.3ab | 16375.0ab |

| 4 ton ha−1 | 201.80 | 17.30 | 4.62 | 41.72 | 408.75 | 7719.1a | 18180.6a |

| 7 ton ha−1 | 206.90 | 16.53 | 4.69 | 39.26 | 410.25 | 6988.0ab | 16504.6ab |

| 14 ton ha−1 | 205.93 | 16.20 | 4.74 | 40.48 | 404.50 | 7106.3ab | 16912.0ab |

| Mean | 202.32 | 16.29 | 4.65 | 39.64 | 404.20 | 6908.01 | 16355.5 |

| P | Ns | Ns | Ns | Ns | Ns | ∗ | ∗ |

| CV (%) | 6.31 | 11.17 | 5.51 | 9.52 | 8.44 | 10.9 | 10.6 |

Note: FDB = full dose of the buffer, FDEA = full dose of exchangeable acidity, PH = plant height, EL = Ear length, ED = Ear diameter, HI = harvest index, TSW = Thousand seed weight, LSD = least significant difference, CV = Coefficient of variation, Ns = non-significant at p > 0.05; ∗ = significant. Means followed by the same letter in a column are not significantly different at p < 0.05.

3.4. Economic analysis

Even though application of 3.5 tons ha−1 lime in drill application method showed better response on the improvement of basic soil chemicals, treatment that received 0.120 tons ha−1 lime and applied through spot application method gave >100% marginal rate of return (MRR) value and highest net benefit (60,897.6 birr) which is economically feasible and acceptable rate in the trail (Tables 6 and 7).

Table 6.

Dominance analysis.

| Treatments | GY (kg ha−1) | TVC (Birr ha−1) | GI (Birr ha−1) | NB (Birr ha−1) | Dominance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (no lime) | 6479.07 | 0.00 | 58311.64 | 58311.64 | |

| 0.060 ton ha−1 | 6628.26 | 332.61 | 59654.34 | 59321.73 | |

| 0.120 ton ha−1 | 6840.31 | 665.23 | 61562.82 | 60897.60 | |

| 0.180 ton ha−1 | 6621.78 | 997.84 | 59596.05 | 58598.21 | D |

| ¼ FDEA (1 ton ha−1) | 6862.42 | 2881.61 | 61761.76 | 58880.14 | D |

| ½ FDEA (2 ton ha−1) | 6871.37 | 5469.10 | 61842.37 | 56373.27 | D |

| ¼ FDB (3.5 ton ha−1) | 6964.25 | 10085.65 | 62678.25 | 52592.60 | D |

| FDEA (4 ton ha−1) | 7719.09 | 10938.20 | 69471.85 | 58533.65 | D |

| ½ FDB (7 ton ha−1) | 6988.03 | 19141.85 | 62892.29 | 43750.43 | D |

| FDB (14 ton ha−1) | 7106.33 | 38283.70 | 63956.95 | 25673.24 | D |

| ∗1kg lime = birr 2.67 and 1kg maize = birr 9.0 | |||||

Table 7.

Marginal rate of return analysis and economical profitability.

| Treatment | TVC (Birr ha−1) | NB (Birr ha−1) | MRR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (no lime) | 0 | 58311.64 | - |

| 0.060 ton ha−1 | 332.61 | 59321.73 | 303.68 |

| 0.120 ton ha−1 | 665.23 | 60897.60 | 473.78 |

Note: GI = gross income, TVC = total variable costs, NB = net benefits, MRR = marginal rate of return, D = Dominance.

4. Conclusions and recommendations

The drill lime application method improved selected soil chemical properties. This application method ameliorated soil acidity with over 200% lime cost reduction advantage comparative to the broadcast application method. Application of different lime rates affected maize grain and biomass yields but did not affect maize yield components. Farmers, who afford to apply much amount of lime, are recommended to apply 3.5 tons ha−1 lime through drill lime application method to improve soil chemical properties quickly. From an economic point of view, the use of 0.12 tons ha−1 lime in micro-dosing application method had an acceptable economic profit. Moreover, further studies are required on multi locations for consecutive years to get more reliable results.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Erkihun Alemu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Yihenew G. Selassie; Birru Yitaferu: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We want to express our deepest and heartfelt thanks to ARARI (Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institution) and Adet Agricultural Research Center for finical support of this work.

References

- Abdenna Deressa, Chewaka Negassa, Geleto Tilahun. 2007. Inventory of Soil Acidity Status in Croplands of central and Western Ethiopia, Utilization of Diversity in Land Use Systems, Sustainable and Organic Approaches to Meet Human Needs; pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Achalu Chimdi, Gebrekidan Heluf, Kibret Kibebew, Abi Tadesse Effects of liming on acidity-related chemical properties of soils of different land use systems in western Oromia, Ethiopia. World J. Agric. Sci. 2012;8(6):560–567. [Google Scholar]

- Adane Buni. Effects of liming acidic soils on improving soil properties and yield of haricot bean. J. Environ. Anal. Toxicol. 2014;5(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Adet Agricultural Research Center . 2002. Agronomic Recommendation. unpublished paper. [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu Seyum. 2008. Decomposition of Growth in Cereal Production in Ethiopia. Background Paper Prepared for a Study on Agriculture and Growth in Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele Shiferaw, Boddupalli M., Prasanna Hellin J., Bänziger M. Crops that feed the world 6 . Past successes and future challenges to the role played by maize in global food security. Food Sec. 2011;3:307–327. [Google Scholar]

- Birhan Abdulkadir, Kassa Sofiya, Desalegn Temesgen, Tadesse Kassu, Haileselassie Mihreteab, Fana Girma, Abera Tolera, Amede Tilahun, Tibebe Degefie. Crop response to fertilizer application in Ethiopia: a review (EJNR) 2017;16 Number 1 and 2. [Google Scholar]

- Birhanu Agumas, Abewa Anteneh, Abebe Dereje, Feyisa Tesfaye, Yitaferu Birru, Desta Gtzaw. In: Proceeding of the 7th and 8th Annual Regional Conferences of Completed Research Activities of Soil and Water Management Research, 25-31 an 13-20 February 2014, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Feyisa Tesfaye., editor. Amhara Agricultural Research Institute; 2016. Effect of lime and Phosphorus on soil health and bread wheat productivity on acidic soils of South Gonder; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner J.M., Mulvaney C.S. In: Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2: Chemical and Microbiological Properties. Page A.L., editor. Agronomy 9; Madison, Wisconsin: 1982. Nitrogen-total; pp. 595–624. [Google Scholar]

- CIMMYT . 1988. From Agronomic Data to Farmer Recommendations. An Economic Training Manual. Completely Revised Edition. Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- CSA . Vol. 1. Addis Ababa; 2014. (Agricultural Sample Survey: Report on Area and Production of Major Crops (Private Peasant Holdings, Meher Season)). [Google Scholar]

- Dagne Wegary, Zelleke Habtamu, Abakemal Demissew, Hussien Temam, Singh H. The combining ability of maize inbred lines for grain yield and reaction to grey leaf spot disease. East Afr. J. Sci. 2008;2:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Dessalegn Tamene, Anbessa Bekele, Adisu Tigist. Influence of lime and phosphorus fertilizer on the acid properties of soils and soybean (Glycine max L.) crops grown in Benshangul-Gumuze Regional State Assosa area. Adv. Crop Sci. Technol. 2017;5(6):4. [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopia Soil Information System (Ethiosis) 2016. Soil Fertility Status and Fertilizer Recommendation Atlas of Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Eyasu Elias. Addis Ababa; Ethiopia: 2016. Soils of the Ethiopian highlands Geomorphology and Properties. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) 2006. Plant Nutrition for Food Security: A Guide for Integrated Nutrient Management. Rome Italy. [Google Scholar]

- FAO and ITPS . Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations and intergovernmental technical panel on Soils; Rome, Italy: 2015. Status of the World’s Soil Resources (SWSR)–main Report. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT . 2010. Statistical Databases and Data-Sets of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Getachew Alemu, Desalegn Temesgen, Debele Tolessa, Ayalew Adela, Taye Geremew, Yirga Chelot. Effect of lime and phosphorus fertilizer on acid soil properties and barley grain yield at Bedi in Western Ethiopia. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017;12(40):3005–3012. [Google Scholar]

- Gitari H.I., Mochoge E.B., Danga O.B. Effect of lime and goat manure on soil acidity and maize (Zea mays L.) growth parameters at Kavutiri, Embu County- Central Kenya. J. Soil Sci. Environ. Manag. 2015;6(10):275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Goedert W.J., Lobato E., Lourenco S. Nutrient use effciency in Brazilian acid soils, nutrient management and plant efficiency. Brazil. Soil Sci. Soc. 1997:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R.J. Effects of liming on phosphate availability in acid soils. Plant Soil. 1982;(3):289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hazelton P., Murphy B. second ed. CSIRO; 2007. Interpreting Soil Test Results: what Do All the Numbers Mean? [Google Scholar]

- Hirpa Legesse, Dechassa Nigussie, Gebeyehu Setegn, Bultosa Geremew, Mekbib Firew. Response to soil acidity of common bean genotypes (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) under field conditions at Nedjo, Western Ethiopia. Sci. Technol. Arts Res. J. 2013;2(3):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, Bennett A.E., Newton A.C., White P.J., McKenzie B.M., George T.S., Pakeman R.J., Bailey J.S., Fornara D.A., Hayes R.C. Science of the Total Environment; 2017. pp. 316–332. (Liming Impacts on Soils, Crops and Biodiversity in the UK : A Review Science of the Total Environment Liming Impacts on Soils, Crops and Biodiversity in the UK: A Review). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafer Dawid, Gebresilassie Hailu. Application of lime for acid soil amelioration and better Soybean performance in SouthWestern Ethiopia. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 2017;7(5):95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasundara H.P.S., Thomso B.D., Tang C. Responses of cool-season grain legumes to soil abiotic stresses. Adv. Agron. 1998;63(C):77–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kebede Dinkecha, Dereje Tsegaye. Effects of liming on physicochemical properties and nutrient availability of acidic soils in Welmera Woreda, central highlands of Ethiopia. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017;(6):102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Komljenovic I., Markovic M., Djurasinovic G., Kovacevic V. The response of maize to liming and phosphorus fertilization with emphasis on weather properties effects. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2015;2(1):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Landon J.R. John Wiley and Sons Inc. Ed.; New York: 1991. Booker Tropical Soil Manual: a Handbook for Soil Survey and Agricultural Land Evaluation in the Tropics and Subtropics. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen Getahun. 2015. Characterization of Agricultural Soils in CASCAPE Intervention Woredas of the Amhara Region. [Google Scholar]

- Mesfin Kassa, Yebo Belay, Habte Abera. Liming effect on yield and yield component of haricot bean (Phaseolus vuglaris L.) varieties grown in acidic soil at Wolaita zone, Ethiopia. Int. J. Soil Sci. 2014;9(2):67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy H.F. Collage of Agriculture HSIU. Experimental Station Bulletin No. 44, Collage of Agriculture. Alemaya, Ethiopia. 1968. A report on fertility status and other data on some soils of Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D.W., Sommers L.E. In: Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2: Chemical and Microbiological Properties. Wisconsin: Madison. Page A.L., Miller R.H., Keeney D.R., editors. 1982. Total carbon, organic carbon and organic matter. [Google Scholar]

- Ndubuisi M.C., Deborah N. The response of maize (Zea mays L.) to different rates of wood-ash application in acid ultisol in Southeast Nigeria. J. Am. Sci. 2010;6(1):53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Oloo K.P. Vol. 5. 2016. Long term effects of lime and phosphorus application on maize productivity in acid soil of Uasin Gishu; pp. 48–55.http://www.skyjournals.org/SJAR (3) [Google Scholar]

- Olsen Sterling Robertson, Cole C.V., Watanabe F.S., Dean L.A. 1954. Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium carbonate. [Google Scholar]

- Opala P.A. Influence of lime and phosphorus application rates on the growth of maize in acid soil. Adv. Agric. 2017:1–5. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlemedihin S., Taye B. National Soil Research Center, Ethiopian Agricultural Research Organization; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 2000. Procedures for Soil and Plant Analysis. Technical paper no.74; p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute . SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2002. A Business Unit of SAS; p. 2751. USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker H.E., McLean E.O., Pratt P.F. Buffer methods for determining the Lime requirement of soils with appreciable amounts of extractable aluminum. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1961;25(4):274–277. [Google Scholar]

- Taye Belachew. 2007. An Overview of Acid Soils Their Management in Ethiopia Paper Presented in the Third International Workshop on Water Management (Wterman) Project. Haramaya, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Tekalign Tadese. Working Document No. 13. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 1991. Soil, plant, water, fertilizer, animal manure and compost analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Tsedeke Abate, Shiferaw Bekele, Menkir Abebe, Wegary Dagne, Kebede Yilma, Tesfaye Kindie, Kassie Menale, Bogale Gezahegn, Tadesse Berhanu, Keno Tolera. Factors that transformed maize productivity in Ethiopia. Food Secur. 2015;7(5) [Google Scholar]

- Van Reeuwijk L.P. Wageningen: Soil Reference and Information center (ISRIC); 1992. Procedures for soil analysis (third ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Wassie Haile, Shiferaw Boke. Mitigation of Soil Acidity and Fertility Decline Challenges for Sustainable Livelihood Improvement: Research Findings from the Southern Region of Ethiopia and its Policy Implications. Awassa Agricultural Research Center; Awassa: 2014. The role of soil acidity and soil fertility management for enhanced and sustained production of wheat in southern Ethiopia; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Yihenew G., Selassie, Suwanarit A., Suwannarat C., Sarobol E. Equations for estimating phosphorus fertilizer requirements from soil analysis for maize ( Zea mays L.) grown on Alfisols of Northwestern Ethiopia. Kasetsart J./Nat. Sci. 2003;37(3):284–295. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.