Abstract

The viral capsid protein of the Seto virus (SeV), a Japanese strain of genogroup I Norwalk-like viruses (NLVs), was expressed as virus-like particles using a baculovirus expression system. An antigen detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay based on hyperimmune antisera to recombinant SeV was highly specific to homologous SeV-like strains but not heterologous strains in stools, allowing us type-specific detection of NLVs.

Norwalk-like viruses (NLVs), one of the four genera in the family Caliciviridae (3), are a genetically and antigenically heterogeneous group of viruses that are a major cause of acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis (1, 13). Detection and molecular characterization of NLVs have been hampered by a lack of cell culture systems and small animal models. However, recent progress in the molecular cloning and sequencing of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and capsid protein genes has enabled us to divide NLVs into at least two genogroups: genogroup I (GI) and genogroup II (GII) (22).

NLVs contain a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome that contains three open reading frames (ORFs) (12, 17). When the ORF2 gene is expressed by a recombinant baculovirus, the recombinant protein spontaneously self-assembles into virus-like particles (VLPs) that are antigenically and morphologically indistinguishable from native virions (4, 5, 6, 9, 11). The VLPs have been successfully used in structural studies (19, 20) and in the development of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for serological diagnosis of NLV infection (4, 5). Though antigen detection ELISAs using hyperimmune antisera raised against the VLPs have been developed to detect NLVs in stools (2, 6, 8), the efficiency is relatively low due to the antigenic diversity of NLVs (10). The expression of antigenically distinct VLPs and production of antisera to VLPs are needed to clarify the antigenic relationship among NLVs.

This paper describes the cDNA cloning and baculovirus expression of the viral capsid gene of the Seto virus (SeV), a member of NLV GI. In addition, we report the development and evaluation of an antigen detection ELISA based on the antisera to the recombinant capsid protein.

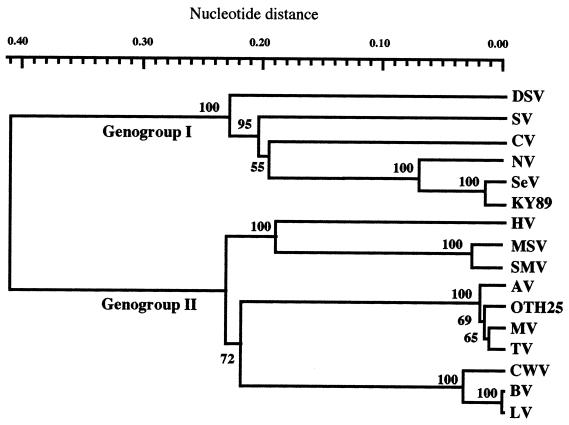

A stool specimen (124/89 in Table 1) from an SeV outbreak was used to clone the capsid gene. The NLV detected in this stool was designated SeV. Viral RNA was extracted from a 10% stool suspension in phosphate-buffered saline using Trizol (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). For cDNA synthesis, oligo(dT)15 (Promega Co., Madison, Wis.) and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL) were used. A seminested PCR was performed to amplify the entire ORF2 gene. The first PCR used forward primer G1F1 (5′-TGCCCGAATTCGTAAATGAT-3′) (positions 5343 to 5362 in the Norwalk virus [NV] genome; Genbank accession no. M87661) and reverse primer G1R0 (5′-GCCATTATCGGCGCARACCAAGCC-3′) (positions 6931 to 6954), and the second PCR used forward primer G1F0 (5′-GTAAATGATGATGGCGTCTAAGGA-3′) (positions 5354 to 5377) and G1R0. An approximately 1.6-kb PCR product was cloned into TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) to generate pCR[SeV]. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the 1.6-kb insert showed that it contained the entire ORF2 of SeV and was predicted to encode a 530-amino-acid capsid protein. A comparison of the ORF2 nucleotide sequence of SeV with those of known NLVs indicated that SeV showed the highest identity with KY89 (97%), followed by NV (89%), Chiba virus (CV) (66%), Southampton virus (62%), and Desert Shield virus (62%). SeV had lower identity with GII NLVs, including the Snow Mountain virus (52%), Hawaii virus (52%), and Mexico virus (52%). The phylogenetic analysis of the ORF2 genes of SeV and representative NLVs indicated that SeV is closest to KY89 (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Detection of NLVs in stools by ELISAs using hyperimmune antisera to rSEV and rCV

| Sample | Result of antigen detection ELISA forb:

|

Result of RT-PCR and Southern hybridization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SeV | CV | ||

| rSEVa | 1.05 | 0.00 | NTc |

| rCVa | 0.00 | 0.93 | NT |

| 121/89 | 1.31 | 0.01 | + |

| 122/89 | 1.61 | 0.00 | + |

| 124/89 | 0.53 | 0.00 | + |

| 125/89 | 0.23 | 0.00 | − |

| 131/89 | 1.48 | 0.01 | + |

| 1381/93 | 0.35 | 0.04 | + |

| 1382/93 | 1.55 | 0.04 | + |

| 663/99 | 0.03 | 0.62 | + |

| 665/99 | 0.04 | 1.32 | + |

| 666/99 | 0.07 | 2.01 | + |

| 669/99 | 0.04 | 0.51 | + |

| 675/99 | 0.01 | 0.28 | + |

| 676/99 | 0.07 | 1.72 | + |

| 680/99 | 0.05 | 1.62 | + |

| 687/99 | 0.06 | 1.04 | + |

Purified VLPs (2 ng/ml) were used as antigens.

OD values at 492 nm. Homologous titers are shown in boldface.

NT, not tested.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram of the ORF2 gene of SeV and known NLVs. The ORF2 genes from four GI NLVs and four GII NLVs were analyzed using a SINCA package (FUJITSU, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), in which tree topology was inferred by UPGMA cluster analysis with the bootstrap option. The numbers at the branching points are the 50% threshold majority consensus values for 100 bootstrap replicates. The known NLV sequences (and GenBank accession numbers) are as follows: NV (M87661), KY89 (L23828), OTH25 (L23830), Southampton virus (SV) (L07418), Desert Shield virus (DSV) (U04469), CV (AB022679), Lorsdale virus (LV) (X86557), Bristol virus (BV) (X76716), Camberwell virus (CWV) (U46500), Toronto virus (TV) (U02030), Mexico virus (MV) (U22498), Snow Mountain virus (SMV) (U70059), Melksham virus (MSV) (X81879), Auckland virus (AV) (U46039), and Hawaii virus (HV) (U07611).

The ORF2 gene of SeV was isolated from pCR[SeV] by digestion with EcoRI and inserted into a baculovirus transfer vector, pVL1392 (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), at the same EcoRI site, to generate pVL[SeV]. Sf9 cells (Riken Cell Bank, Tsukuba, Japan) were cotransfected with 50 ng of linearized wild-type Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus DNA (BaculoGold kit; Pharmingen) and 1 μg of pVL[SeV] by the Lipofectin-mediated method. A recombinant baculovirus, designated as Ac[SeV], was selected by two rounds of plaque purification. Tn5 cells (Invitrogen) were infected with Ac[SeV] at a multiplicity of infection of 10 and harvested at 6 days postinfection (p.i.) at 26.5°C. The expression of recombinant proteins was monitored by sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (16). Samples were prepared for electrophoresis by boiling for 3 min prior to loading. A major protein band with a molecular mass of 58 kDa was observed in the infected cells at 2 days p.i., and the expression reached its maximum at 6 days p.i. (data not shown). The observed mass of 58 kDa for the expressed protein was in agreement with the predicted molecular mass calculated from the 530-amino-acid sequence encoded by the SeV ORF2. The supernatant of the infected cells at 6 days p.i. was clarified at 10,000 × g for 30 min and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 2 h in a Beckman TLA-45 rotor. The pellet was suspended in a few drops of water and examined by electron microscopy. Uniform, round, empty VLPs with diameters of 38 nm were observed at a concentration of 200 particles per electron micrograph field (data not shown). A typical yield of the VLPs was 0.1 to 0.2 mg per 2 × 107 Tn5 cells after CsCl equilibrium gradient centrifugation followed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation (9).

Hyperimmune antisera to the purified recombinant SeV (rSeV) were prepared in rabbits (four doses of 250 μg of protein/dose with Freund's complete adjuvant). The specificity of rabbit hyperimmune antisera to rSeV or rCV (14, 15) was tested in parallel with indirect ELISAs. The ELISA method employed was identical to the ELISA for rNV (2, 11). ELISA titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of antiserum giving an optical density (OD) at 492 nm of >0.15. The titers of anti-rSeV hyperimmune sera to homologous antigen were fourfold higher than those of sera to heterologous rCV (1:4,096,000 versus 1:1,024,000). The titers of anti-rCV hyperimmune sera to homologous antigen were 32-fold higher than those of sera to heterologous rSeV (1:8,192,000 versus 1:256,000). Relatively high cross-reactivity was not unexpected because broad reactivity, especially between strains included in the same genogroup, has been reported (7, 18).

An antigen detection ELISA was developed using the rabbit hyperimmune antisera to rSeV. Microplates were coated with the rabbit preimmune or hyperimmune sera (1:5,000 dilution) to capture the antigen in the stool specimens, and peroxidase-conjugated antiserum to rSeV was used as the detector antibody. The sample was considered positive when the difference between the OD values for hyperimmune and preimmune sera was >0.15 and the ratio of the hyperimmune OD to preimmune OD was >2 (15). In control experiments, hyperimmune antisera to rSeV and rCV efficiently captured 0.2 ng of the homologous antigen but did not capture the heterologous antigen (Table 1). Preimmune sera captured neither the homologous nor heterologous VLPs at any concentration. A panel of 15 stool specimens collected from patients during two SeV-associated outbreaks and a CV-associated outbreak, which had been characterized by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) and Southern hybridization, was tested in parallel with the SeV and CV antigen detection ELISAs. In SeV-associated outbreaks, six of seven specimens (all except 125/89) were positive by RT-PCR and Southern hybridization using an SeV-specific biotinylated probe, which was prepared by PCR using pCR[SeV] as a template, as previously described (21). The probe was specific for the SeV-like strains, but not for other GI or GII NLVs (data not shown). In the CV-associated outbreak, CV-like strains from eight stool specimens were confirmed by Southern hybridization with a CV-specific probe. The antigen-detection ELISA for SeV recognized the viral antigens in stool specimens in the SeV outbreaks, but these samples were negative for the CV assay. In contrast, the CV assay detected viral antigens in a CV-associated outbreak but not in the SeV-associated outbreaks. SeV and CV can be differentiated by antigen detection ELISAs, although the two viruses belong to the same genogroup.

SeV showed 97% nucleotide identity (97% amino acid identity) in the capsid region with KY89 and 87% nucleotide identity (98% amino acid identity) with NV, indicating that SeV is nearly identical to KY89. SeV and KY89 were isolated in 1989 in Japan, while NV was isolated in 1968 in the United States. Although NV and KY89 have not been tested by our antigen detection ELISA, we predict that these three viruses are antigenically related.

The hyperimmune antisera to rSeV and rCV revealed minor cross-reactivities to each other when VLP antigens from cell culture were used to coat the plate to capture antibodies. In contrast, the antigen detection ELISAs, using the antibodies to coat the plate to capture antigens, were highly specific. Similarly high specificities have also been shown in the ELISAs for the detection of NV, Mexico virus, and Grimsby virus (2, 6, 8). The expression of more VLPs representing different antigenic types of NLVs, as well as the subsequent development of ELISAs based on the expressed VLPs, is necessary for the diagnosis and antigenic classification of NLVs.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data of SeV has been deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases with the accession number AB031013.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Health Sciences Research Grants for Research on Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases, Research on Environmental Health, Research on Pharmaceutical and Medical Safety, and Research on Health Sciences Focusing on Drug Innovation from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan. We are grateful for the support of the Interministerial Cooperative Basic Research Core System from the Agency of Science and Technology, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Estes M K, Atmar R L, Hardy M E. Norwalk and related diarrhea viruses. In: Richmann D D, Whitley R J, Hayden F G, editors. Clinical virology. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone Inc.; 1997. pp. 1073–1095. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham D Y, Jiang X, Tanaka T, Opekun A R, Madore H P, Estes M K. Norwalk virus infection of volunteers: new insights based on improved assays. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:34–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green K Y, Ando T, Balayan M S, Clarke I N, Estes M K, Matson D O, Nakata S, Neill J D, Struddert M J, Thiel H J. Caliciviridae. In: van Regenmortel C F M, Bishop D, Carsten E, Estes M K, Lemon S, Maniloff J, Maya M, McGeoch D, Pringle C R, Wickner R, editors. Virus taxonomy, in press. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press, Inc.; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green K Y, Kapikian A Z, Valdesuso J, Sosnovtsev S, Treanor J J, Lew J F. Expression and self-assembly of recombinant capsid protein from the antigenically distinct Hawaii human calicivirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1909–1914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1909-1914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green K Y, Lew J F, Jiang X, Kapikian A Z, Estes M K. Comparison of the reactivities of baculovirus-expressed recombinant Norwalk virus capsid antigen with those of the native Norwalk virus antigen in serologic assays and some epidemiologic observations. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2185–2191. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2185-2191.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hale A D, Crawford S E, Ciarlet M, Green J, Gallimore C, Brown D W G, Jiang X, Estes M K. Expression and self-assembly of Grimsby virus: antigenic distinction from Norwalk and Mexico viruses. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:142–145. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.142-145.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hale A D, Lewis D C, Jiang X, Brown D W. Homotypic and heterotypic IgG and IgM antibody responses in adults infected with small round structured viruses. J Med Virol. 1998;54:305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang X, Cubitt D, Hu J, Dai X, Treanor J, Matson D O, Pickering L K. Development of an ELISA to detect MX virus, a human calicivirus in the Snow Mountain agent genogroup. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2739–2747. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-11-2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang X, Matson D O, Ruiz-Palacios G M, Hu J, Treanor J, Pickering L K. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of a Snow Mountain agent-like calicivirus capsid protein. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1452–1455. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1452-1455.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang X, Wang J, Estes M K. Characterization of SRSVs using RT-PCR and a new antigen ELISA. Arch Virol. 1995;140:363–374. doi: 10.1007/BF01309870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang X, Wang M, Graham D Y, Estes M K. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of the Norwalk virus capsid protein. J Virol. 1992;66:6527–6532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6527-6532.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang X, Wang M, Wang K, Estes M K. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology. 1993;195:51–61. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapikian A Z, Estes M K, Chanock R M. Norwalk group of viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 783–810. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasuga K, Tokieda M, Ohtawara M, Utagawa E, Yamazaki S. Small round structured virus associated with an outbreak of acute gastroenteritis in Chiba, Japan. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1990;43:111–121. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.43.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi, S., K. Sakae, K. Natori, N. Takeda, T. Miyamura, and Y. Suzuki. A serotype-specific antigen ELISA in the detection of Chiba viruses in stool specimens. J. Med. Virol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambden P R, Caul E O, Ashley C R, Clarke I N. Sequence and genome organization of a human small round-structured (Norwalk-like) virus. Science. 1993;259:516–519. doi: 10.1126/science.8380940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noel J S, Ando T, Leite J P, Green K Y, Dingle K E, Estes M K, Seto Y, Monroe S S, Glass R I. Correlation of patient immune responses with genetically characterized small round-structured viruses involved in outbreaks of nonbacterial acute gastroenteritis in the United States, 1990 to 1995. J Med Virol. 1997;53:372–383. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199712)53:4<372::aid-jmv10>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad B V, Hardy M E, Dokland T, Bella J, Rossmann M G, Estes M K. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science. 1999;286:287–290. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prasad B V V, Rothnagel R, Jiang X, Estes M K. Three-dimensional structure of baculovirus-expressed Norwalk virus capsids. J Virol. 1994;68:5117–5125. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5117-5125.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeda N, Sakae K, Agboatwalla M, Isomura S, Hondo R, Inouye S. Differentiation between wild and vaccine-derived strains of poliovirus by stringent microplate hybridization of PCR products. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:202–204. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.202-204.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Jiang X, Madore H P, Gray J, Desselberger U, Ando T, Seto Y, Oishi I, Lew J F, Green K Y, Estes M K. Sequence diversity of small, round-structured viruses in the Norwalk virus group. J Virol. 1994;68:5982–5990. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5982-5990.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]