Key Points

Question

What is the immune humoral response to 2 or 3 doses of the BNT162b2 (BioNTech; Pfizer) vaccine in patients treated with anticancer agents for solid cancer?

Findings

In this cohort study including 163 patients, a third vaccine dose strengthened the immune response in 75% of the patients treated with chemotherapy or targeted therapy presenting a weak humoral response after the second dose.

Meaning

The data of this study appear to support the use of a third vaccine dose as a booster dose among patients with active cancer treatment for solid tumors.

Abstract

Importance

Patients with solid cancer are more susceptible to develop SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe complications; the immunogenicity in patients treated with anticancer agents remains unknown.

Objective

To assess the immune humoral response to 2 or 3 doses of the BNT162b2 (BioNTech; Pfizer) vaccine in patients treated with anticancer agents.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A prospective observational cohort study was conducted between February 1 and May 31, 2021. Adults treated with anticancer agents who received 2 or 3 doses of vaccine were included; of these, individuals with a weak humoral response 1 month after the second dose received a third injection.

Interventions

Quantitative serologic testing of antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2 was conducted before vaccination and during follow-up.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Humoral response was evaluated with a threshold of anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike protein antibody levels at 1000 arbitrary units (AU)/mL to neutralize less-sensitive COVID-19 variants.

Results

Among 163 patients (median [range] age, 66 [27-89] years, 86 men [53%]) with solid tumors who received 2 or 3 doses of vaccine, 122 individuals (75%) were treated with chemotherapy, 15 with immunotherapy (9%), and 26 with targeted therapies (16%). The proportions of patients with an anti-S immunoglobulin G titer greater than 1000 AU/mL were 15% (22 of 145) at the time of the second vaccination and 65% (92 of 142) 28 days after the second vaccination. Humoral response decreased 3 months after the second dose. Treatment type was associated with humoral response; in particular, time between vaccine and chemotherapy did not interfere with the humoral response. Among 36 patients receiving a third dose of vaccine, a serologic response greater than 1000 AU/mL occurred in 27 individuals (75%).

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this cohort study appear to support the use of a third vaccine dose among patients with active cancer treatment for solid tumors.

This cohort study examines the use of a third dose of the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with cancer.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has a substantial effect on populations with fragile health and is associated with an increased mortality rate in patients with cancer compared with the general population.1 Patients with cancer have been defined as a high-risk population for priority access to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.2 However, patients with immune deficiency or those receiving immunosuppressive treatment were excluded from SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trials, and the immunogenicity in patients treated with anticancer agents remains unknown. To date, few reports of immunogenicity after 3 vaccine doses in patients treated for solid tumors have been published.3,4

We conducted this study to evaluate the immunogenicity of the recommended 2 or 3 doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in patients with active cancer receiving systemic therapy. This study focused on the type of oncologic treatment (cytotoxic vs immunotherapy vs targeted treatment) and the timing of vaccination.

Methods

A prospective, single-center observational cohort study including patients receiving treatment for solid cancer from Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil, France, was conducted between February 1 and May 31, 2021. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies. An information sheet was given to the patients and oral informed consent was obtained; participants did not receive financial compensation. The study was approved by the Groupe Hospitalier AP-HP-Nord Ethics Committee.

Active cancer was defined as histologic confirmation of solid cancer under treatment within the previous 6 weeks or starting treatment during the next 2 weeks. All data were prospectively collected in a standardized format, including cancer diagnosis, cancer stage, anticancer therapy, and biological results before vaccination. Data on race and ethnicity were not obtained because these data are highly protected by French legislation. The ethics committee was not asked to allow statistics on race and ethnicity.

All patients received 2 doses of the BNT162b2 mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (BioNTech; Pfizer) on days 0 and 21. Patients with a history of COVID-19 or positive SARS-CoV-2 antinucleocapsid antibodies before vaccination were excluded. A third vaccine dose was offered to patients with a weak humoral response 1 month after the second dose, defined as an anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (anti-S) antibody level less than 1000 arbitrary units (AU)/mL.5 SARS-CoV-2 anti-S antibody testing was performed at the time of the first, second, and third vaccine doses 28 days and 3 months (±7 days) after the second and third vaccine doses.

SARS-CoV-2 Anti-S Immunoglobulin G Antibody Testing

We used a commercial enzyme-linked immunoassay (Architect; Abbott) validated for clinical use to assess patient serum titers of anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike protein immunoglobulin G (IgG). The assay detects IgG directed to the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike S1 subunit. Results were acquired on the Architect i1000 analyzer (Abbott). Values greater than 21 AU/mL were considered positive, as specified by the manufacturer.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed on the R statistical software platform, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A χ2 test or Fisher exact test was performed for comparisons of proportions. A logistic regression using seroconversion as the outcome and risk factors as independent variables was performed for multivariable analysis. With 2-sided, unpaired testing, the significance threshold was set at P < .05.

Results

We enrolled 163 patients (median age, 66 [range, 27-89] years; 86 men [53%]; 77 women [47%]) receiving oncologic treatment for solid cancer with no history of COVID-19 and a negative SARS-CoV-2 antinucleocapsid serologic test before vaccination, indicating the lack of prior exposure to COVID-19. Among these patients, 122 received chemotherapy (75%), 26 received targeted oral therapy (16%), and 15 received immunotherapy (9%) (Table). Median follow-up was 14 weeks (IQR, 8-16 weeks).

Table. Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors.

| Variable | Before vaccination (n = 163), negative serologic test, No. | 1 mo After first vaccination (n = 145)a,b | 1 mo After second vaccination (n = 142)c,d | 1 mo After third vaccination (n = 36)e,f | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-S titer, No./total No. (%) | P value, χ2 | Logistic regression | Anti-S titer, No./total No. (%) | P value, χ2 | Logistic regression | Anti-S titer, No./total No. (%) | |||||||

| <1000 AU/mL | >1000 AU/mL | OR (95% CI) | P value, χ2 | <1000 AU/mL | >1000 AU/mL | OR (95% CI) | P value, χ | <1000 AU/mL | >1000 AU/mL | ||||

| All | 163 | 123/145 (85) | 22/145 (15) | NA | NA | NA | 50/142 (35) | 92/142 (65) | NA | NA | NA | 9/36 (25) | 27/36 (75) |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Male | 86 (53) | 60/73 (82) | 13/73 (18) | .37 | 0.85 (0.3-2.5) | .77 | 23/73 (32) | 50/73 (68) | .34 | 0.73 (0.3-1.6) | .43 | 4/15 (27) | 11/15 (73) |

| Female | 77 (47) | 63/72 (87) | 9/72 (13) | NA | 27/69 (39) | 42/69 (61) | NA | 5/21 (24) | 16/21 (76) | ||||

| Age, y | |||||||||||||

| ≤70 | 100 | 72/88 (82) | 16/88 (18) | .21 | 0.67 (0.2-1.9) | .46 | 27/84 (32) | 57/84 (68) | .36 | 0.66 (0.3-1.4) | .29 | 5/21 (24) | 16/21 (76) |

| >70 | 63 | 51/57 (89) | 6/57 (11) | NA | 23/58 (40) | 35/58 (60) | NA | 4/15 (27) | 11/15 (73) | ||||

| Type of cancer | |||||||||||||

| Digestive | 67 (41) | 49/57 (86) | 8/57 (14) | .41 | NA | NA | 16/57 (28) | 41/57 (72) | .50 | NA | NA | 3/10 (30) | 7/10 (70) |

| Urologic | 40 (25) | 27/35 (77) | 8/35 (23) | NA | NA | 13/34 (38) | 21/34 (62) | NA | NA | 3/8 (38) | 5/8 (62) | ||

| Breast | 51 (31) | 44/49 (90) | 5/49 (10) | NA | NA | 19/47 (40) | 28/47 (60) | NA | NA | 3/17 (18) | 14/17 (82) | ||

| Other | 5 (3) | 3/4 (75) | 1/4 (25) | NA | NA | 2/4 (50) | 2/4 (50) | NA | NA | 0/1 | 1/1 (100) | ||

| Category of cancer | |||||||||||||

| Neoadjuvant/adjuvant | 42 (26) | 35/39 (90) | 4/39 (10) | .60 | NA | NA | 14/41 (34) | 27/41 (66) | .14 | NA | NA | 2/13 (15) | 11/13 (85) |

| M+ L1 | 54 (33) | 40/48 (83) | 8/48 (17) | NA | NA | 11/44 (25) | 33/44 (75) | NA | NA | 1/8 (13) | 7/8 (88) | ||

| M+≥L1 | 67 (41) | 48/58 (83) | 10/58 (17) | NA | NA | 25/57 (44) | 32/57 (56) | NA | NA | 6/15 (40) | 9/15 (60) | ||

| Corticosteroid treatment,g | |||||||||||||

| No | 147 (90) | 112/130 (86) | 18/130 (14) | .19 | 2.06 (0.5-8.6) | .32 | 44/129 (34) | 85/129 (66) | .39 | 0.38 (0.1-1.4) | .14 | 9/34 (26) | 25/34 (74) |

| Yes | 16 (10) | 11/15 (73) | 4/15 (27) | NA | 6/13 (46) | 7/13 (54) | NA | 0/2 | 2/2 (100) | ||||

| Lymphocytes at the time of first vaccination, /μL | |||||||||||||

| ≤1000 | 47 (29) | 37/43 (86) | 6/43 (14) | .86 | 0.91 (0.3-2.6) | .87 | 18/42 (43) | 24/42 (57) | .27 | 1.48 (0.7-3.2) | .32 | 2/14 (14) | 12/14 (86) |

| >1000 | 99 (61) | 73/86 (85) | 13/86 (15) | NA | 28/85 (33) | 57/85 (67) | NA | 6/18 (33) | 12/18 (67) | ||||

| Type of treatment | |||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 122 (75) | 94/108 (87) | 14/108(13) | .004 | 5.4 (1.5-20.2) | .02 | 40/106 (38) | 66/106 (62) | .22 | 3.29 (0.7-16.2) | .34 | 8/30 (27) | 22/30 (73) |

| Targeted therapy | 26 (16) | 22/24 (92) | 2/24 (8) | NA | 8/22 (36) | 14/22 (64) | NA | 1/6 (17) | 5/6 (83) | ||||

| Immunotherapy | 15 (9) | 7/13 (54) | 6/13 (46) | NA | 2/14 (14) | 12/14 (86) | NA | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Cytotoxic chemotherapy schedule (n = 122) | |||||||||||||

| Daily | 19 (16) | 15/17 (88) | 2/17 (12) | .97 | NA | NA | 4/16 (25) | 12/16 (75) | .51 | NA | NA | 1/3 (33) | 2/3 (67) |

| Weekly | 21 (17) | 16/19 (84) | 3/19 (16) | NA | NA | 6/17 (35) | 11/17 (65) | NA | NA | 1/5 (20) | 4/5 (80) | ||

| Every 2 wk | 52 (43) | 38/43 (88) | 5/43 (12) | NA | NA | 17/45 (38) | 28/45 (62) | NA | NA | 4/11 (36) | 7/11 (64) | ||

| Every 3 wk | 30 (24) | 26/30 (87) | 4/30 (13) | NA | NA | 13/28 (46) | 15/28 (54) | NA | NA | 2/11 (18) | 9/11 (82) | ||

| Timing between vaccination and chemotherapy (n = 110), h | |||||||||||||

| ≤48 | 8 (7) | 5/7 (71) | 2/7 (29) | .53 | NA | NA | 2/7 (29) | 5/7 (71) | .90 | NA | NA | 1/2 (50) | 1/2 (50) |

| >48 | 102 (84) | 78/89 (88) | 11/89 (12) | NA | NA | 34/88 (39) | 54/88 (61) | NA | NA | 5/25 (20) | 20/25 (80) | ||

Abbreviations: anti-S, anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike protein; AU, arbitrary unit; M+L1, metastatic first line of treatment; M+≥L1, metastatic second or more line of treatment; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

SI conversion: To convert lymphocytes to ×109 per liter, multiply by 0.001.

Data missing on 18 patients. At the time of the second vaccination: 3 patients had died, 10 patients discontinued the serologic follow-up because of tumor progression, and 5 patients were lost to follow-up.

Anti-S titer, median, 30.4 AU/mL (IQR, 0-243.4 AU/mL).

Data missing on 21 patients. One month after the second vaccination: 11 patients had died, 5 patients discontinued the serologic follow-up because of tumor progression, and 5 patients were lost to follow-up.

Anti-S titer, median, 1996.3 AU/mL (IQR, 498.2-5575.3 AU/mL).

At the time of analysis, 36 patients had received a third dose of vaccine.

Anti-S titer, median, 7435.3 AU/mL (IQR, 989.8-16 103.5 AU/mL).

Corticosteroid dose greater than or equal to 10 mg of prednisone equivalent for 4 weeks or more.

At the time of the second dose, 22 of 145 patients (15%) had anti-S IgG titers greater than 1000 AU/mL (median, 30.4 AU/mL [IQR, 0-243.4 AU/mL]). One month after the second dose, the number of patients with anti-S IgG titers greater than 1000 AU/mL increased to 92 of 142 (65%) (median, 1996.3 AU/mL [IQR, 498.2-5575.3 AU/mL]).

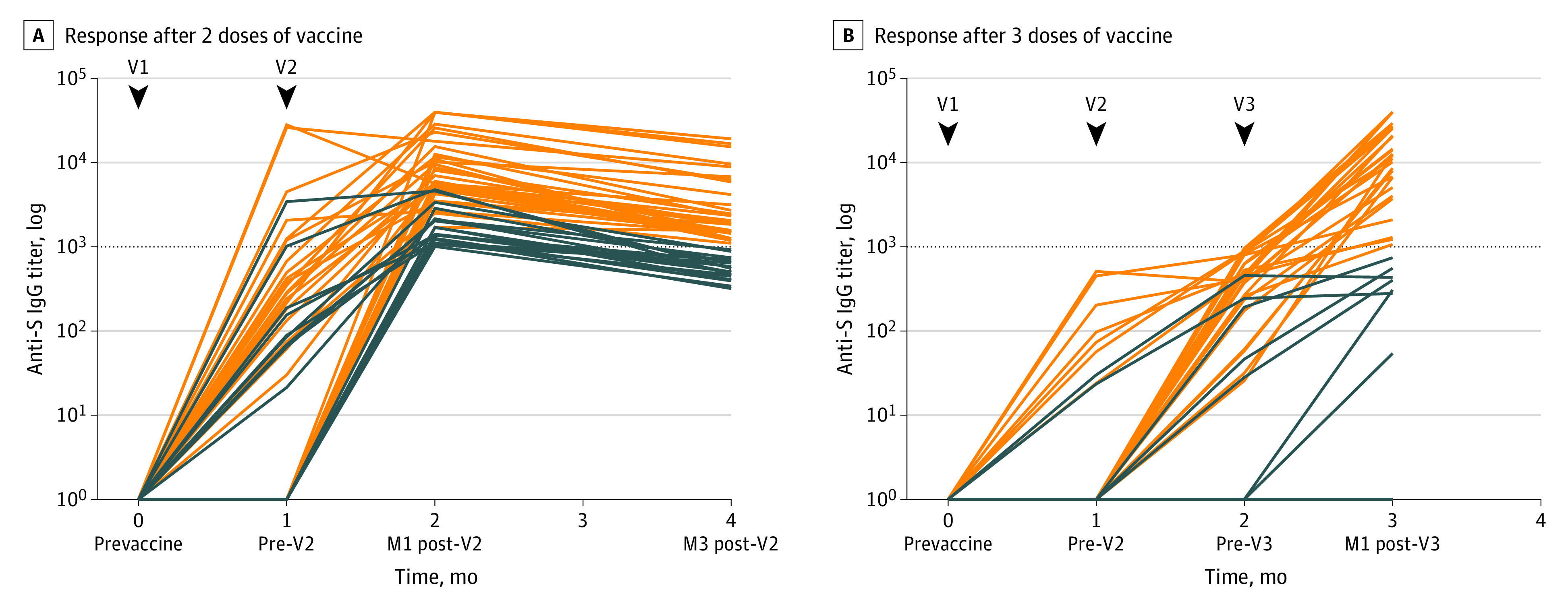

In concordance with local practices, we offered a third dose to patients with a weak humoral response, considering a cutoff of anti-S IgG titer less than 1000 AU/mL 28 days after the second dose.5,6 The third dose improved the humoral response in 27 of 36 patients (75%) (median, 7435.3 AU/mL [IQR, 989.8-16103.5 AU/mL]) (Figure).

Figure. Humoral Immune Response After 2 or 3 Doses of BNT162b2 Vaccine.

Anti-S immunoglobulin G (IgG) titer: horizontal dotted line indicates the cutoff for positivity (1000 arbitrary units [AU]/mL) at the first (V1), second (V2), and third (V3) doses of BNT162b2 vaccine. A, Humoral immune response after 2 doses of vaccine: orange lines indicate the antibody titers of patients with an immune response greater than 1000 AU/mL at 3 months after the second dose. Blue lines indicate the antibody titer of patients who lowered their immune response at 3 months (n = 64). B, Humoral immune response after 3 doses of vaccine: orange lines indicate the antibody titers of patients with a strong immune response greater than 1000 AU/mL at 1 month after a third dose of mRNA vaccine (n = 36). Blue lines indicate the antibody titer of patients with a persistent weak immune response less than 1000 AU/mL at 1 month after a third dose of mRNA vaccine. M1 indicates first month; M3, third month; V1, first dose of BNT162b2 vaccine; V2, second dose of BNT162b2 vaccine; V3, third dose of BNT162b2 vaccine.

Because the administration of 3 doses of vaccine was debated when the study was initiated, patients with anti-S IgG titers greater than 1000 AU/mL were not offered a third vaccine dose. We observed a global decrease of their anti-S IgG levels 3 months after the second dose, with 27 of 64 patients (42%) then presenting with titers less than 1000 AU/mL (median, 1352.5 AU/mL [IQR, 569.8-2186.4 AU/mL]).

Age, sex, cancer type (digestive, urologic, and breast), cancer category (neoadjuvant, adjuvant, metastatic first, or >1 line), lymphopenia, and use of corticosteroids 4 or more weeks before the vaccine injection were not associated with the level of humoral response at the time of the second dose or 28 days after the second dose. In multivariable analysis, patients treated with chemotherapy or targeted therapy had a lower anti-S IgG level than those receiving immunotherapy (odds ratio, 5.4; 95% CI, 1.5-20.2; P = .02). Schedules of administration (daily, weekly, every 2 weeks, and every 3 weeks) and time between vaccination and intravenous chemotherapy administration (≤48 vs >48 hours) were not associated with the intensity of the humoral response.

No severe adverse events were observed after the third dose. No patient presented symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection after 2 doses of vaccine or developed antinucleocapsid antibody response.

Discussion

A third vaccine booster dose strengthened the immune response in most patients with a weak humoral response after the second dose.6,7 Most patients who remained seronegative after 2 doses showed an emerging humoral response 28 days after the third dose.

To date, few studies have reported a prolonged serologic follow-up of 3 months after 2 doses of BNT162b2 vaccine.8,9 Immunogenicity after 2 doses of vaccine seems to be stronger in patients with solid cancer compared with those who have hematologic cancer or have undergone solid organ transplantation.8,10 COVID-19 guidelines have evolved since this study was designed, and a third dose is now recommended at 6 months for adults older than 60 years. The results of this study suggest that a third dose of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine could be needed at 1 month after the second dose in patients receiving active cancer treatment.

Patients treated with targeted therapy (mainly tyrosine kinase inhibitors or anti-CDK4/6 inhibitors) had the same humoral immune response profile as those treated with chemotherapy, and patients treated with immunotherapy had a stronger humoral response. We did not find any factor associated with a weak humoral response in patients receiving chemotherapy or targeted therapy: delay between vaccination and chemotherapy (≤48 vs >48 hours from the previous and next injection) was not associated with the intensity of the humoral response. This result must be confirmed in larger cohorts, because the organization of vaccination schedule and chemotherapy cycles is a daily challenge.11

Limitations

This study has limitations, including the absence of B- and T-cell function analysis. Correlation between serologic titers and protection against infection remains unclear, although neutralizing antibodies have been shown to be associated with immune protection from symptomatic infection.12,13 Several in vitro thresholds correlating with high levels of neutralizing antibodies against the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein have been proposed.3,14,15 Owing to concerns about reduced sensitivity of the Delta SARS-CoV-2 variant to antibody neutralization, we selected a threshold of 1000 AU/mL.5,16 Statistical significance of multivariable analysis should be interpreted with caution, and the lack of association with some variables could be the consequence of the relatively small number of patients, which also prevented us from performing comparative analyses after the third dose. The number of patients without iterative blood sampling was mainly owing to the poor prognosis associated with cancer.

Conclusions

In this cohort study of patients treated with anticancer agents, the use of an early third SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dose appeared to be capable of stimulating humoral immune response. Patients treated with targeted therapy had the same humoral response profile as those treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy. The timing between vaccine administration and intravenous chemotherapy cycle was not associated with humoral response.

References

- 1.Tougeron D, Hentzien M, Seitz-Polski B, et al. ; for Thésaurus National de Cancérologie Digestive (TNCD); réseau de Groupes Coopérateurs en Oncologie (GCO); Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (UNICANCER); Association de Chirurgie Hépato-Bilio-Pancréatique et Transplantation (ACHBT); Association de Recherche sur les Cancers Gynécologiques-Groupes d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’étude des Cancers Ovariens et du Sein (ARCAGY-GINECO); Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD); Groupe Coopérateur multidisciplinaire en Oncologie (GERCOR); Groupe d’Oncologie Radiothérapie Tête et Cou-Intergroupe ORL (GORTEC-Intergroupe ORL); Intergroupe Francophone de Cancérologie Thoracique (IFCT); InterGroupe Coopérateur de Neuro-Oncologie/Association des Neuro-Oncologues d’Expression Française (IGCNO-ANOCEF); Société Française de Chirurgie Digestive (SFCD); Société Française d’Endoscopie Digestive (SFED); Société Française de Radiothérapie Oncologique (SFRO); Société Française de Radiologie (SFR); Société Nationale Française de Colo-Proctologie (SNFCP); Société Nationale Française de Gastroentérologie (SNFGE) . Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination for patients with solid cancer: review and point of view of a French oncology intergroup (GCO, TNCD, UNICANCER). Eur J Cancer. 2021;150:232-239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.03.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrière J, Re D, Peyrade F, Carles M. Current perspectives for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination efficacy improvement in patients with active treatment against cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2021;154:66-72. . doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gounant V, Ferré VM, Soussi G, et al. Efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in thoracic cancer patients: a prospective study supporting a third dose in patients with minimal serologic response after two vaccine doses. medRxiv. Preprint posted August 13, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.08.12.21261806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Goshen-Lago T, Waldhorn I, Holland R, et al. Serologic status and toxic effects of the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients undergoing treatment for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(10):1507-1513. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallais F, Gantner P, Bruel T, et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies persist for up to 13 months and reduce risk of reinfection. medRxiv. Preprint posted May 17, 202 . doi: 10.1101/2021.05.07.21256823 [DOI]

- 6.Kamar N, Abravanel F, Marion O, Couat C, Izopet J, Del Bello A. Three doses of an mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):661-662. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2108861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Shakankery KH, Kefas J, Crusz SM. Caring for our cancer patients in the wake of COVID-19. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(1):3-4. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0843-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliakim-Raz N, Massarweh A, Stemmer A, Stemmer SM. Durability of response to SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccination in patients on active anticancer treatment. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(11):1716-1718. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.4390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldhorn I, Holland R, Goshen-Lago T, et al. Six-month efficacy and toxicity profile of BNT162B2 vaccine in cancer patients with solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(10):2430-2435. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thakkar A, Gonzalez-Lugo JD, Goradia N, et al. Seroconversion rates following COVID-19 vaccination among patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(8):1081-1090.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sudan A, Iype R, Kelly C, Iqbal MS. Optimal timing for COVID-19 vaccination in oncology patients receiving chemotherapy? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2021;33(4):e222. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2020.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1205-1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niu L, Wittrock KN, Clabaugh GC, Srivastava V, Cho MW. A structural landscape of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain. Front Immunol. 2021;12:647934. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.647934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebinger JE, Fert-Bober J, Printsev I, et al. Antibody responses to the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):981-984. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01325-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng S, Phillips DJ, White T, et al. ; Oxford COVID Vaccine Trial Group . Correlates of protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(11):2032-2040. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01540-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Planas D, Veyer D, Baidaliuk A, et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596(7871):276-280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]