Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased negative emotions and decreased positive emotions globally. Left unchecked, these emotional changes might have a wide array of adverse impacts. To reduce negative emotions and increase positive emotions, we tested the effectiveness of reappraisal, an emotion-regulation strategy that modifies how one thinks about a situation. Participants from 87 countries and regions (n = 21,644) were randomly assigned to one of two brief reappraisal interventions (reconstrual or repurposing) or one of two control conditions (active or passive). Results revealed that both reappraisal interventions (vesus both control conditions) consistently reduced negative emotions and increased positive emotions across different measures. Reconstrual and repurposing interventions had similar effects. Importantly, planned exploratory analyses indicated that reappraisal interventions did not reduce intentions to practice preventive health behaviours. The findings demonstrate the viability of creating scalable, low-cost interventions for use around the world.

The COVID-19 pandemic is increasing negative emotions and decreasing positive emotions around the globe1–10. Concurrently, individuals are reporting that COVID-19 is having a negative impact on their psychological functioning and mental health4,11,12. For example, individuals report sleeping less, consuming more alcohol or other drugs or substances, having trouble concentrating because their mind is occupied by COVID-19, and having more fights with their partner or loved ones, some escalating to domestic violence1,9,13.

These disturbing trends are caused partly by heightened levels of negative emotion and diminished levels of positive emotion, which have been found to contribute to a number of negative psychological, behavioural and health consequences. These include increased risk of anxiety and depressive disorders as well as other forms of psychopathology14; impaired social connections15; increased substance use16–18; compromised immune system functioning19–21; disturbed sleep22; increased maladaptive eating23,24; increased aggressive behaviour25,26; impaired learning27; worse job performance28,29; and impaired economic decision-making30,31.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds around the world, we believe it is crucial to mitigate expected adverse outcomes by reducing negative emotions and increasing positive emotions. Such a change in emotions is central to increasing psychological resilience, a multifaceted concept that involves adaptive emotional responses in the face of adversity32–34. Reappraisal—an emotion regulation strategy that involves changing how one thinks about a situation with the goal of influencing one’s emotional response35—is a promising candidate as an intervention to increase psychological resilience due to its adaptability, simplicity and efficiency34,36–38. In contrast to less effective emotion-regulation strategies such as suppression, reappraisal generally leads to more successful regulation (d = 0.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.35, 0.56] in changing emotion experience in a meta-analysis39; see caveats about interpreting effect sizes in past research in Methods, ‘Sampling plan’). In particular, over the short term, reappraisal leads to decreased reports of negative emotion and increased reports of positive emotion40–42, as well as corresponding changes both in peripheral physiological responses43–45 and central physiological responses46–53. Over the longer term, reappraisal is associated with stronger social connections54; higher academic achievement55,56; enhanced psychological well-being57; fewer psychopathological symptoms58,59; better cardiovascular health60,61, and greater resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic62.

Despite these shorter-term and longer-term benefits, most people do not reappraise consistently63,64, which has motivated efforts to teach people to use reappraisal (reviewed in refs. 65,66). For example, in the context of anxiety, reappraisal training led to reduced intrusive memories67 and increased emotion-regulation self-efficacy68,69. Reappraisal training also led to long-lasting changes in the neural representation of unpleasant events70.

Although demand characteristics are always a concern when examining the effects of reappraisal (given that one is teaching people to change their thinking in order to change how they’re feeling, and then asking them how they feel)71, the wide array of self-report and non-self-report outcomes39–53 that show reappraisal effects across studies increases confidence that these effects are real. It is also encouraging to note that reappraisal generally outperforms other types of emotion regulation such as suppression, even though demand characteristics appear comparable across regulation conditions39. In addition, evidence indicates that reappraisal interventions can influence emotional outcomes even in intensely challenging contexts in which people are often unmotivated to regulate their emotions72. For example, a brief reappraisal training conducted in the context of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and replicated in the context of the Colombian conflict73, has been found to contribute to reduced intergroup anger and increased support for conciliatory political policies74.

As part of the attempt of the Psychological Science Accelerator (PSA) to address pressing questions related to the psychological impact of COVID-19, the current study aimed to use reappraisal interventions to enhance psychological resilience in response to the pandemic. To maximize the impact of these interventions, this project had a global reach of large, diverse samples via the PSA’s network75, and employed highly scalable methods that were translated for use around the world. In order to make stronger and clearer inferences, our design included two reappraisal interventions that were compared with two control conditions, an active control and a passive control.

For our reappraisal interventions, we examined two theoretically defined forms of reappraisal76—reconstrual and repurposing. Reconstrual involves changing how a situation was construed or mentally represented in a way that changes the emotional responses related to the situation. Examples of reconstrual in response to COVID-19 include: “Washing hands, avoiding touching my face, keeping a safe distance…There are simple and effective things I can do to protect myself and my loved ones from getting sick and to stop the spread of the virus” and “I know from world history that keeping calm and carrying on gets us through tough times”. Repurposing involves focusing on a potentially positive outcome that could come from the current situation in a way that changes the emotional response to it. Examples of repurposing in response to COVID-19 include: “This situation is helping us realize the importance of meaningful social connections, and helping us understand who the most important people in our lives are” and “Medical systems are now learning to deal with amazing challenges, which will make them much more resilient in the future”. For our active control condition, we asked participants to reflect on their thoughts and feelings as they unfolded. Meta-analyses have revealed that reflecting on one’s thoughts and feelings produces small but reliable salutary effects (d = 0.07, 9% CI = [0.05, 0.17] in improving psychological health, including emotional responses77,78). Examples of reflecting in response to COVID-19 are: “I really wish we could find a vaccine soon” and “This situation is changing so fast, and I don’t know how the future will develop”. By asking participants in this condition to actively use a strategy that is likely to have a positive effect, we sought to match expectancy and demand across reappraisal and active control conditions. For our passive control condition, we asked participants to respond as they naturally do, which is a commonly used passive control condition in prior research on emotion regulation (for a meta-analysis, see ref. 39).

In comparing conditions, we chose to distinguish between negative and positive emotional responses, as previous evidence suggests that the two are clearly separable79,80. Specifically, we hypothesized that our reappraisal interventions would lead to reduced negative emotional responses (hypothesis 1) and increased positive emotional responses (hypothesis 2) compared with both control conditions combined. While both reconstrual and repurposing strategies involve changing thinking, we hypothesized that the reconstrual intervention would lead to greater decreases in negative emotional responses than the repurposing intervention (hypothesis 3) and that the repurposing intervention would lead to greater increases in positive emotional responses than the reconstrual intervention (hypothesis 4). We theorized that reconstruing one’s situation should primarily decrease negative emotions, because it typically focuses on ameliorating the problem at hand. The reconstrual intervention is most similar to a previously studied subtype of reappraisal called reappraising emotional stimulus, which has been investigated mainly on negative emotions and has a d = 0.38 and 95% CI = [0.21, 0.55] for changing emotion experience39. Repurposing one’s situation, by contrast, should primarily increase positive emotions because it usually calls to mind positive experiences. Repurposing is similar to a few previously examined types of reappraisals, such as benefit finding and positive reappraisal, both of which are primarily associated with positive outcomes81,82 (Methods, ‘Sampling plan’ provides further detail).

In testing these hypotheses, we planned to use orthogonal contrasts that make two primary comparisons, while keeping all other comparisons exploratory (Table 1 provides further detail). The first comparison contrasted both the reappraisal conditions combined with both the active control condition and the passive control condition combined for negative (hypothesis 1) and positive (hypothesis 2) emotions. The second comparison contrasted the reconstrual and repurposing interventions for negative (hypothesis 3) and positive (hypothesis 4) emotions. One attractive feature of comparisons between reappraisal conditions is that there is no reason to assume that demand or expectancies would differ across these reappraisal conditions.

Table 1 |.

Contrast structure of testing hypotheses 1–4 (with unit weighting)

| Active control | Passive control | Reconstrual | repurposing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast 1 (hypotheses 1–2) | 0.5 | 0.5 | −0.5 | −0.5 |

| Contrast 2 (hypotheses 3–4) | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | −0.5 |

One potential concern about the current design was that the emotion-regulation interventions might reduce preventive health behaviours (for example, maintaining social distance and washing hands) that could potentially be motivated by negative emotions. Some research on the connection between emotions and health behaviour suggests that increased negative emotions such as fear do not seem to be a strong motivator for changing one’s health behaviour83. Furthermore, positive emotions augmented by the reappraisal interventions may contribute to a greater tendency to undertake health behaviours84,85. For example, positive emotions can lead to higher medication adherence86. To ensure that our interventions would not adversely impact any relevant health behaviours, we took two steps. First, during the instructions, we clarified that—in some cases—negative emotions such as fear and sadness may be helpful, and that it is up to each person to determine when an emotion is unhelpful or not and to downregulate only those emotions that are unhelpful. Second, to assess whether our training would lead to reduced vigilance, we specifically measured and examined intentions to follow stay-at-home orders and wash hands in exploratory analyses.

In addition, we conducted other exploratory analyses. These analyses included testing the impact of our reappraisal interventions on negative and positive anticipated emotions and intentions to enact potentially harmful versus beneficial behaviours associated with these emotions (details described in Methods, ‘Measures’), and assessed whether the effects of our reappraisal interventions, if any, were moderated by motivation to use the given strategy71, belief in the effectiveness of the given strategy87, or demographics (gender39, socioeconomic status88,89 or country or region90 (hereafter country/region) (particularly in light of the differing levels of impact of COVID-19 in any given country/region at any given point in time)).

Results

Final sample size and demographics.

We collected 27,989 responses between May 2020 and October 2020. After implementing preregistered exclusions (see detail in https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.4878591.v1) and an additional exclusion of nine duplicate IDs, our final sample included 21,644 participants from 87 countries/regions (63.41% female, 35.34% male, 0.45% other genders, 0.56% preferred not to say and 0.24% missing responses to the gender question; participants were aged 31.91 ± 14.52 yr (mean ± s.d.); see Supplementary Table 1 for sample size per country/region and Supplementary Table 2 for sample size per month). Of the 87 countries/regions represented, 37 had more than 200 participants, surpassing our 95% power criterion based on simulations in our power analysis (see detail in Methods, ‘Power analysis’).

We preregistered two exclusion criteria. First, as planned, we excluded participants who answered both multiple choice manipulation check questions incorrectly, and found that conditions had similar proportions of such participants (0.55%), Holm’s adjusted P values > 0.999. Second, as planned, we excluded participants who completed fewer than 50% of the questions in the study, and found that the passive control condition had fewer such participants (16.17%) than the other three conditions (23.86% in the active control condition, 24.41% in the reconstrual condition and 23.90% in the repurposing condition), Holm’s adjusted P < 0.001. One possible explanation for this difference is that the instructions given to participants in the passive control condition were shorter than those given in the other conditions, requiring less cognitive effort to read and less time to complete the study. Applying both exclusion criteria, the overall exclusion rate was significantly lower in the passive control condition (16.71%) than in the other three conditions (24.47% in the active control condition, 24.99% in the reconstrual condition and 24.37% in the repurposing condition), Holm’s adjusted P < 0.001. To rule out concerns related to differences in exclusion rates, we repeated all preregistered analyses on the full sample. Reassuringly, all patterns, statistical significance and conclusions remained unchanged when analyses were repeated on the full sample (Supplementary Table 3).

Preregistered analyses.

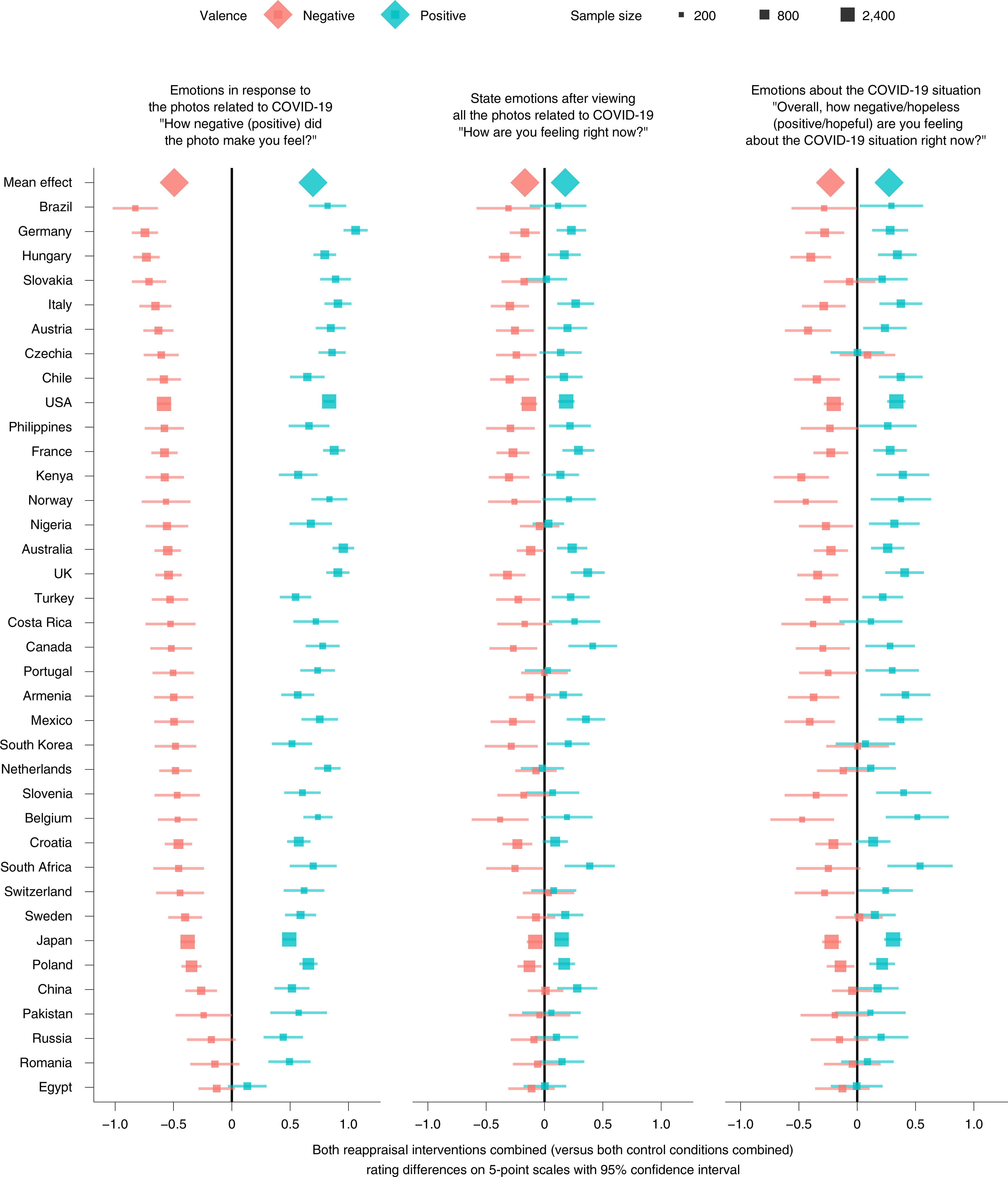

We included all 87 countries/regions in all analyses regardless of their sample sizes, except for Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2, where the 37 countries/regions with n ≥ 200 were analysed separately by country/region. Effect sizes, frequentist statistics and Bayes factors for each of our hypotheses are presented in Table 2. Raw means and standard deviations for each relevant measure are provided in Table 3. Details of analytical models are described in Methods.

Fig. 1 |. Effect sizes of both reappraisal interventions combined (versus both control conditions combined) on primary outcomes by country/region.

In almost all of the 37 countries/regions in which there were more than 200 participants, both reappraisal interventions combined (versus both control conditions combined) decreased negative emotional responses and increased positive emotional responses for primary outcome measures (emotions in response to the photos, state emotions after viewing all the photos, and emotions about the COVID-19 situation). Effect sizes are raw mean differences on five-point scales without adjusting for covariates. Confidence intervals are based on the t distribution. Countries/regions are ordered by decreasing effect sizes of negative emotions in response to the photos, and larger dots reflect larger samples (supplementary Fig. 1 presents the countries/regions in alphabetical order.).

Table 2 |.

Effect sizes, frequentist statistics and Bayes factors for each preregistered hypothesis

| Row number | Hypothesis | B (s.e.m.) | Standard deviation of B by country/region | t statistic (d.f.) | Holm’s adjusted P value | Cohen’s d [95% CI] | log10(BF) [under robustness check] | Verbal interpretation132 of log10(BF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Reappraisal interventions (versus control) would reduce negative emotions in response to the photos (hypothesis 1a). | 0.513 (0.021) | 0.129 | 23.973 (52.36) | <0.001 | 0.392 [0.360, 0.425] | 29.41 [29.47] | log(BF) > 2 represents “extreme evidence in favour of HA”; 2 > log(BF) > 1.5 represents “very strong evidence in favour of HA”; 1.5 > log(BF) > 1 represents “strong evidence in favour of HA”; 1 > log(BF) > 0.5 represents “moderate evidence in favour of HA”; 0.5 > log(BF) > −0.5 represents “inconclusive evidence”; −0.5 > log(BF) > −1 represents “moderate evidence in favour of H0”; −1 > log(BF) > −1.5 represents “strong evidence in favour of H0”; −1.5 > log(BF) > −2 represents “very strong evidence in favour of H0”; −2 > log(BF) represents “extreme evidence in favour of H0”. |

| 3 | Reappraisal interventions (versus control) would reduce negative state emotions (hypothesis 1b). | 0.185 (0.013) | 0.064 | 14.401 (36.39) | <0.001 | 0.313 [0.270, 0.357] | 15.61 [15.15] | |

| 4 | Reappraisal interventions (versus control) would reduce negative emotions about the COVID-19 situation (hypothesis 1c). | 0.241 (0.019) | 0.082 | 12.570 (30.67) | <0.001 | 0.239 [0.201, 0.277] | 13.26 [12.92] | |

| 5 | Reappraisal interventions (versus control) would increase positive emotions in response to the photos (hypothesis 2a). | 0.711 (0.025) | 0.166 | 28.301 (59.18) | <0.001 | 0.590 [0.549, 0.631] | 34.65 [34.80] | |

| 6 | Reappraisal interventions (versus control) would increase positive state emotions (hypothesis 2b). | 0.178 (0.012) | 0.064 | 14.263 (42.69) | <0.001 | 0.326 [0.281, 0.372] | 15.90 [15.42] | |

| 7 | Reappraisal interventions (versus control) would increase positive emotions about the COVID-19 situation (hypothesis 2c). | 0.263 (0.018) | 0.070 | 14.809 (31.21) | <0.001 | 0.266 [0.230, 0.301] | 15.48 [15.23] | |

| 8 | Reconstrual would lead to greater decreases in negative emotional responses in response to the photos than repurposing (hypothesis 3a). | −0.056 (0.023) | 0.107 | −2.438 (33.48) | 0.041 | −0.043 [−0.078, −0.008] | 0.25 [−0.47] | |

| 9 | Reconstrual would lead to greater decreases in negative state emotions than repurposing (hypothesis 3b). | −0.005 (0.016) | 0.069 | −0.321 (29.67) | 0.751 | −0.008 [−0.063,0.046] | −1.09 [−1.87] | |

| 10 | Reconstrual would lead to greater decreases in negative emotions about the COVID-19 situation than repurposing (hypothesis 3c) | 0.068 (0.022) | 0.045 | 3.139 (30.61) | 0.011 | 0.067 [0.024,0.112] | 1.02 [0.32] | |

| 11 | Repurposing would lead to greater increases in positive emotions in response to the photos than reconstrual (hypothesis 4a). | 0.137 (0.022) | 0.113 | 6.176 (46.79) | <0.001 | 0.114 [0.077, 0.151] | 5.37 [4.84] | |

| 12 | Repurposing would lead to greater increases in positive state emotions than reconstrual (hypothesis 4b). | −0.006 (0.011) | Random slopes by country/region were not included for the model to converge | −0.526 (20,340) | 0.599 | −0.011 [−0.049, 0.028] | −1.39 [−2.00] | |

| 13 | Repurposing would lead to greater increases in positive emotions about the COVID-19 situation than reconstrual (hypothesis 4c). | −0.047 (0.026) | 0.109 | −1.781 (37.46) | 0.166 | −0.047 [−0.100, 0.005] | −0.41 [−0.93] |

All 87 countries/regions were included in the preregistered analyses regardless of their sample sizes. The signs of B, t-statistic and Cohen’s d are adjusted such that positive (negative) values indicate being consistent (inconsistent) with the direction specified in a hypothesis. For hypotheses 1–2, B reflects the difference on the original five-point scales between the average of the means of the two control conditions and the average of the means of the two reappraisal intervention conditions. For hypotheses 3–4, B reflects the difference on the original five-point scales between the mean of the reconstrual condition and the mean of the repurposing condition. Degrees of freedom (d.f.) vary due to random slopes133. Cohen’s d is calculated as the raw mean difference divided by the square root of the pooled variance of all the random components. HA, alternative hypothesis; H0, null hypothesis.

Table 3 |.

Raw mean and s.d. values for outcomes

| Outcome | Reappraisal interventions | Control conditions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstrual (n = 5,078) | Repurposing (n = 5,421) | Active control (n = 5,349) | Passive control (n = 5,796) | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| Negative emotions in response to the photos | 2.77a (0.80) | 2.71b (0.77) | 3.29c (0.83) | 3.19d (0.84) |

| Positive emotions in response to the photos | 2.47a (0.81) | 2.62b (0.79) | 1.86c (0.72) | 1.84d (0.73) |

| Negative state emotions | 2.32a (0.90) | 2.31a (0.90) | 2.52b (0.95) | 2.48b (0.95) |

| Positive state emotions | 3.17a (0.88) | 3.18a (0.87) | 2.99b (0.88) | 2.98b (0.90) |

| Negative emotions about the COVID-19 situation | 2.71a (1.08) | 2.77b (1.07) | 2.99c (1.10) | 2.97c (1.10) |

| Positive emotions about the COVID-19 situation | 2.91a (1.05) | 2.88a (1.04) | 2.65b (1.06) | 2.59c (1.06) |

| Exploratory outcomes | ||||

| Intention to follow stay-at-home orders stringently | 5.42a (1.79) | 5.44a (1.77) | 5.41a (1.80) | 5.45a (1.77) |

| Intention to wash hands regularly for at least 20 s | 5.82a (1.53) | 5.82ab (1.50) | 5.82ab (1.51) | 5.76b (1.56) |

| Frequency of natural response | 3.49a (1.35) | 3.53b (1.35) | 4.00c (1.17) | 4.56d (0.79) |

| Frequency of using reflecting | 3.92a (1.11) | 3.90a (1.14) | 4.25b (0.97) | 3.91a (1.20) |

| Frequency of using reconstrual | 3.80a (1.09) | 3.73b (1.14) | 3.06c (1.27) | 2.75d (1.34) |

| Frequency of using repurposing | 3.89a (1.13) | 4.15b (1.01) | 3.21c (1.31) | 3.12d (1.34) |

| Motivation to use the given strategy | 6.14a (1.12) | 6.17a (1.12) | 6.26b (1.04) | 6.43c (1.00) |

| Belief in the effectiveness of the given strategy | 5.00a (1.68) | 5.03a (1.69) | 4.80b (1.76) | 4.44c (1.90) |

| Global change in negative feelings | 2.82a (0.94) | 2.75b (0.93) | 3.19c (0.92) | 3.17c (0.88) |

| Global change in positive feelings | 3.28a (0.91) | 3.33a (0.91) | 2.92b (0.92) | 2.92b (0.89) |

| Anticipated negative emotions | 2.31a (0.90) | 2.30a (0.89) | 2.45b (0.92) | 2.44b (0.94) |

| Anticipated positive emotions | 3.26a (0.88) | 3.26a (0.87) | 3.13b (0.86) | 3.11b (0.89) |

Values are displayed as raw mean (s.d.). Sample sizes (n) presented in the second row reflect the numbers of participants after preregistered exclusion. Sample sizes vary by outcome because we dropped incomplete cases on an analysis-by-analysis basis. All primary outcomes were assessed on five-point scales. The following four exploratory outcomes were assessed on seven-point scales: intention to follow stay-at-home orders stringently, intention to wash hands regularly for at least 20 s, motivation to use the given strategy, and belief in the effectiveness of the given strategy. The remaining exploratory outcomes were assessed on five-point scales. Within each row, means that do not share a superscript differ at P < 0.05; two-tailed, Holm’s method for adjustment. For instance, means both marked with a do not differ significantly, but means marked with a and b differ significantly from each other.

Hypotheses regarding the shared effects of two brief reappraisal interventions.

Consistent with the main hypotheses of the study, both reappraisal interventions combined (versus both control conditions combined) significantly decreased negative emotional responses (hypothesis 1) and significantly increased positive emotional responses (hypothesis 2) across all primary outcome measures (emotions in response to the photos related to COVID-19 from various news sources, state emotions after viewing all the photos and emotions about the COVID-19 situation; Table 2, rows 2–7; details of these measures are described in Methods). As shown in Fig. 1, this finding was consistent across the 37 countries/regions in which there were more than 200 participants (although all 87 countries/regions were included in the analysis testing hypotheses regardless of their sample size, only the 37 countries/regions with n ≥ 200 were analysed separately by country/region for Fig. 1). For example, in comparing participants’ immediate negative emotional responses to the photos related to the COVID-19 situation, data from 33 out of the 37 (89%) countries/regions showed significant effects of the reappraisal interventions in the hypothesized direction. None of the 37 countries/regions’ data revealed a statistically significant result in the opposite direction.

Hypotheses regarding the unique effects of the two reappraisal interventions.

Results revealed little to no support for our hypotheses regarding the differences between reconstrual and repurposing, as neither was reliably better than the other at reducing negative emotions or increasing positive emotions across outcomes (Table 2, rows 8–13; Supplementary Fig. 2). We hypothesized that reconstrual would produce greater decreases in negative emotional responses than repurposing (hypothesis 3), and data revealed supportive evidence for only one outcome (negative emotions about the COVID-19 situation; Table 2, row 10) out of the three measures of negative emotions. The other two negative emotion outcome measures did not support that hypothesis. One outcome (negative emotions in response to the photos; Table 2, row 8) revealed that repurposing had significantly stronger effects in decreasing negative emotional responses than reconstrual, whereas the Bayes factor indicated inconclusive evidence. Another outcome (negative state emotions; Table 2, row 9) revealed no significant difference between types of reappraisal, and the Bayes factor indicated strong evidence in favour of the null hypothesis.

We also hypothesized that repurposing would produce greater increases in positive emotional responses than reconstrual (hypothesis 4), and data revealed supportive evidence for only one outcome (positive emotions in response to the photos; Table 2, row 11) out of the three measures of positive emotions. The other two outcome measures of positive emotions revealed no significant differences between the two reappraisal conditions. The Bayes factors indicated strong evidence in favour of the null hypothesis for one outcome (positive state emotions; Table 2, row 12) and inconclusive evidence for another outcome (positive emotions about the COVID-19 situation; Table 2, row 13). Overall, there were no consistent differences across outcomes between reconstrual and repurposing in reducing negative emotions or increasing positive emotions in the current experimental context. We examined potential reasons for these findings in the exploratory analyses and in the discussion section.

Exploratory analyses.

To better understand the impact of the reappraisal interventions, we conducted four sets of exploratory analyses. First, we examined pairwise comparisons between conditions (each of the reappraisal conditions versus each of the control conditions, and the active control condition versus the passive control condition) for our primary outcomes (emotions in response to the photos, state emotions after viewing all the photos and emotions about the COVID-19 situation). Second, we assessed the effect of reappraisal interventions on four exploratory outcomes (behavioural intentions to practice preventive health behaviours, participants’ engagement with emotion regulation strategies, global change in emotions, and anticipated emotions). Third, we assessed four sets of potential moderators of reappraisal interventions’ effects (motivation to use the given strategy71, belief in the effectiveness of the given strategy87, demographics39,88–90 and lockdown status). Finally, we contextualised reappraisal interventions’ effect sizes on negative emotions by comparing them with effect sizes of lockdown status and self-isolation due to symptoms. Details of analytical models are reported in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

Pairwise comparisons of conditions on primary outcomes.

In the first set of exploratory analyses, we examined the extent to which each of the reappraisal conditions differed from each of the control conditions for our primary outcomes (emotions in response to the photos, state emotions after viewing all the photos and emotions about the COVID-19 situation). Pairwise comparisons for all primary outcomes produced results consistent with the pattern of evidence for hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2. Each of the repurposing and reconstrual conditions (versus each of the control conditions) significantly decreased negative emotional responses and significantly increased positive emotional responses (Ps < 0.001; Table 3).

We also examined whether the active and passive control conditions differed from each other at the level of pairwise comparisons. Among the three primary outcome measures of negative emotional responses, one was significantly higher in the active control condition than in the passive control condition (negative emotions in response to the photos: B = 0.091 ± 0.015, t(20,740) = 6.192, P < 0.001, d = 0.070, 95% CI = [0.048, 0.093]), while the other two showed no significant differences (negative state emotions: B = 0.022 ± 0.011, t(20,400) = 1.933, P = 0.053, d = 0.037, 95% CI = [−0.001, 0.075]; negative emotions about the COVID-19 situation: B = 0.005 ± 0.022, t(26.01) = 0.221, P = 0.827, d = 0.005, 95% CI = [−0.040, 0.047]). Among the three primary outcome measures of positive emotional responses, two were significantly higher in the active control condition than in the passive control condition (positive emotions in response to the photos: B = 0.039 ± 0.013, t(20,740) = 2.918, P = 0.004, d = 0.033, 95% CI = [0.011, 0.054]; positive emotions about the COVID-19 situation: B = 0.053 ± 0.019, t(233.7) = 2.805, P = 0.005, d = 0.053, 95% CI = [0.015, 0.091]), while one showed no significant differences (positive state emotions: B = 0.009 ± 0.010, t(20,350) = 0.858, P = 0.391, d = 0.017, 95% CI = [−0.021, 0.054]). Thus, effects produced by the active control condition versus the passive control condition differed infrequently. When they did differ, differences were small in magnitude, inconsistent in direction, and slightly smaller in effect size than was suggested by previous meta-analyses77 (d = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.17]).

Effects of reappraisal interventions on four exploratory outcomes.

Details of exploratory outcomes can be found in Methods and Fig. 2. Descriptive statistics and pairwise comparisons for exploratory outcomes can be found in Table 3. Here we focus on the contrast between the two reappraisal interventions combined and the two control conditions combined.

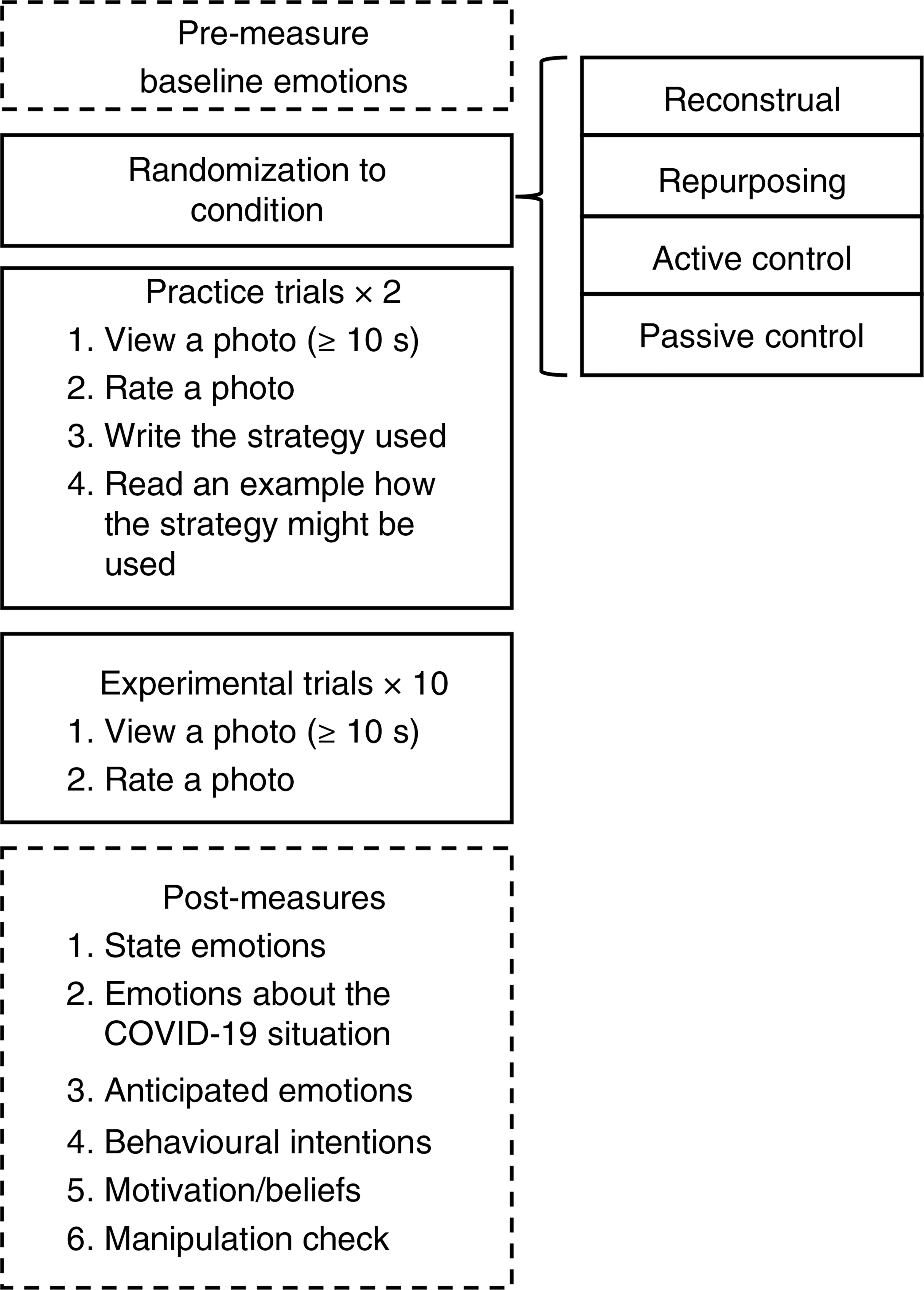

Fig. 2 |. Overview of the experiment.

Participants in the passive control condition did not have the fourth step in the practice trials.

Behavioural intentions to practice preventive health behaviours.

To address the concern that reappraisal interventions might reduce preventive health behaviours (by reducing negative emotions such as fear), we asked about participants’ behavioural intentions to follow stay-at-home orders stringently and to wash their hands regularly for at least 20 s the following week. We found that reappraisal interventions (versus both control conditions combined) did not significantly change intentions to follow stay-at-home orders (B = 0.009 ± 0.024, t(15.04) = 0.38, P = 0.709, d = 0.005, 95% CI = [−0.023, 0.032]) or to wash hands (B = 0.034 ± 0.020, t(20,740) = 1.69, P = 0.091, d = 0.022, 95% CI = [−0.004, 0.048]). Pairwise comparisons revealed that the only significant difference was that participants in the reconstrual condition reported higher intentions to wash their hands than those in the passive control condition (B = 0.077 ± 0.028, t(20,740) = 2.714, Holm’s adjusted P = 0.040, d = 0.051, 95% CI = [0.014, 0.087]). These results thus provide preliminary evidence that reappraisal interventions did not significantly reduce intentions to practice preventive health behaviours.

Participants’ engagement with emotion-regulation strategies.

To better understand participants’ engagement with emotion-regulation strategies when viewing the photos related to COVID-19, we examined participants’ self-reported frequency of using different strategies when viewing the photos, motivation to use their given strategy, and belief in the effectiveness of their given strategy.

Providing confidence in the effectiveness of the manipulation, we found that participants in each of the four conditions reported using the strategy instructed in their condition more frequently than using the other strategies (see Table 3). It is noteworthy that participants in the two reappraisal conditions reported using both reconstrual and repurposing more frequently than those in either control conditions rather than primarily using only the form of reappraisal instructed in their condition. This finding may help explain the lack of differences between the two reappraisal conditions on our primary outcomes.

Next, we examined participants’ motivation to follow the given instructions, as well as participants’ belief that the given strategy could influence their emotions. We found that participants in the two reappraisal interventions (versus both control conditions combined) reported being significantly less motivated to follow their given instructions while viewing the photos (B = −0.192 ± 0.016, t(20.87) = −11.62, P < 0.001, d = −0.183, 95% CI = [−0.215, −0.152]), but reported significantly greater belief in the effectiveness of their given strategy (B = 0.420 ± 0.053, t(52.05) = 7.97, P < 0.001, d = 0.233, 95% CI = [0.175, 0.290]). Thus, the reappraisal conditions were effective in changing emotions despite the fact that participants in reappraisal conditions reported being less motivated to follow the instructions than participants in the control conditions.

Global change of emotions.

At the end of the study, we asked participants how they felt compared with at the beginning of the study. We found that reappraisal interventions (versus both control conditions combined) significantly reduced global negative feelings (B = −0.397 ± 0.026, t(45.29) = 15.30, P < 0.001, d = −0.432, 95% CI = [−0.489, −0.377]) and significantly increased global positive feelings (B = 0.378 ± 0.023, t(45.49) = 16.75, P < 0.001, d = 0.423, 95% CI = [0.373, 0.473]). These findings suggest that the effects are not specific to items in the immediate proximity of the manipulations.

Anticipated emotions.

To gain insight into the potential longer-term effects of reappraisal interventions, we asked participants how they anticipated they would feel the following week. We found that reappraisal interventions (versus both control conditions combined) significantly reduced negative anticipated emotions (B = −0.125 ± 0.012, t(41.99) = −10.27, P < 0.001, d = −0.205, 95% CI = [−0.245, −0.166]) and significantly increased positive anticipated emotions (B = 0.125 ± 0.008, t(13.07) = 15.58, P < 0.001, d = 0.227, 95% CI = [0.197, 0.256]). These findings suggest that participants anticipated that reappraisal strategies would be useful in improving their emotional well-being in the future.

Exploratory moderators of intervention effects.

Prior research suggests that emotion-regulation interventions lead to better results when the participants are: motivated to regulate their emotions71, led to believe in the effectiveness of regulation87, female (versus male)39, from lower (versus higher) socioeconomic status88,89, and from Western (versus Eastern) cultures90. We examined these as well as lockdown status (as a proxy for differing levels of impact of COVID-19) as potential moderators on our primary outcomes (emotions in response to the photos, state emotions after viewing all the photos, and emotions about the COVID-19 situation).

Controlling for baseline emotions, results of multilevel models revealed that two of the variables moderated intervention effects across all six primary outcomes. Specifically, the higher the scores on motivation to use the given strategy and on belief in the effectiveness of the given strategy were, the more effective the interventions were (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 and Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Two variables (gender and employment status) moderated intervention effects on four of the six primary outcomes: Females (versus males) and individuals who had no employment and no income (versus those who had employment and income or versus those with no employment but with income) showed stronger effects of the intervention (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10). One variable moderated intervention effects on two of the six outcomes: the higher a country/region scored on Hofstede’s91 index of individualism, the more effective the intervention was in increasing positive emotions in response to the photos and increasing positive emotions about the COVID-19 situation among participants from that country/region (Supplementary Table 8). Subjective socioeconomic status, education level, and lockdown status significantly moderated no more than one of the six outcomes, which would be unlikely to hold after correction for multiple comparisons (Supplementary Tables 11–13). Full, detailed results are reported in the Supplementary Information.

Contextualising reappraisal interventions’ effect sizes.

To facilitate interpretation of reappraisal effect sizes, it is helpful to compare them to effect sizes of other factors that may have also contributed to differences in participants’ emotions. One such candidate for comparison is differences in emotional experience as a function of lockdown status and of self-isolation due to symptoms. Assuming that lockdown or self-isolation due to symptoms impacted participants’ emotions, emotional changes caused by these factors could be compared to the ones caused by our interventions in order to get a sense of the impact of our intervention.

With negative state emotions as the outcome variable, we examined lockdown status and self-isolation due to symptoms, respectively, as a fixed variable in two separate multilevel models with random by-country/region slopes and random by-country/region intercepts to estimate the pure effect size of each variable (as lockdown status and self-isolation due to symptoms were correlated, entering both variables simultaneously in the same model may generate biased estimates). We found that participants whose areas were in full lockdown reported more negative state emotions than participants whose areas were not in lockdown (B = 0.154 ± 0.040, t(37.56) = 3.812, P < 0.001, d = 0.159, 95% CI = [0.075, 0.243]), and participants whose areas were in partial lockdown reported more negative state emotions than participants whose areas were not in lockdown (B = 0.094 ± 0.027, t(27.25) = 3.531, P = 0.001, d = 0.097, 95% CI = [0.041, 0.155]). We also found that participants who were self-isolating due to flu-like or cold-like symptoms reported more negative state emotions than participants who were not self-isolating due to flu-like or cold-like symptoms (B = 0.175 ± 0.044, t(25.83) = 3.981, P < 0.001, d = 0.183, 95% CI = [0.092, 0.283]). As shown in Table 2 for hypothesis 1b, participants who were in the two reappraisal conditions reported less negative state emotions than participants who were in the two control conditions (B = 0.185 ± 0.013, t(36.39) = 14.401, P < 0.001, d = 0.313, 95% CI = [0.270, 357]). In addition, the amount of variance explained by fixed effects in a model with only lockdown status as a fixed variable is marginal92 R2 = 0.003. The amount of variance explained by fixed effects in a model with only self-isolation due to symptoms as a fixed variable is marginal92 R2 = 0.001. The amount of variance explained by fixed effects in a model with only the contrast between the two reappraisal conditions and the two control conditions as the fixed variable is marginal92 R2 = 0.013. Across different measures of effect size, it is notable that the effects of reappraisal interventions on state negative emotions were of similar or even larger magnitude than the effects of lockdown status or self-isolation due to symptoms. This comparison suggests that reappraisal interventions could help to alleviate the emotional toll caused by lockdown and self-isolation. Thus, we believe that the effects of reappraisal interventions are not only statistically significant but also practically meaningful.

Discussion

The current study had two main goals. The first was to examine the shared effects of two brief reappraisal interventions (versus both passive and active control conditions) on negative and positive emotions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and to determine whether these effects were similar or different across countries/regions and COVID-19 situations. The second goal was to examine the potentially unique effects of the two reappraisal interventions—reconstrual and repurposing—on negative and positive emotions.

Regarding the first goal, we predicted and found that both reappraisal interventions (versus both control conditions combined) consistently decreased negative emotional responses (hypothesis 1) and consistently increased positive emotional responses (hypothesis 2) across all primary outcome measures: immediate emotions in response to each photo about the COVID-19 situation, state emotions after viewing all the photos related to the COVID-19 situation and overall emotions about the COVID-19 situation. Exploratory analyses suggested that both reappraisal interventions also improved participants’ reported emotions compared with at the beginning of the study and the emotions they anticipated feeling in the future.

Further exploratory analyses suggested that despite substantial local variations in how severe the pandemic was at the time data were collected and cultural differences in how people understand and respond to emotions90,93, the intervention effects appeared in almost all of the countries/regions we studied. For example, in comparing participants’ immediate negative emotional responses to the photos related to the COVID-19 situation, 33 out of the 37 (89%) countries/regions with high statistical power (over 200 participants) showed statistically significant effects of reappraisal interventions. Although reappraisal interventions tended to have larger effects among females (versus males), and among unemployed individuals without income, the effects were largely unqualified by education level, subjective socioeconomic status, and whether a participant’s country/region was under lockdown.

Regarding the second goal, we predicted that reconstrual would be more effective at reducing negative emotions than repurposing (hypothesis 3), but repurposing would be more effective at increasing positive emotions than reconstrual (hypothesis 4). We found little to no support for these hypotheses, as neither was reliably better than the other at reducing negative emotions or increasing positive emotions across outcomes. The finding that the two forms of reappraisal were similarly effective at regulating emotions in the context of COVID-19 is consistent with the idea that the pandemic offers a wide array of affordances both for construing emotional situations in different ways, thus enabling reconstrual, and for evaluating these situations in light of different goals, thus enabling repurposing76. This implies that it may be beneficial to combine both strategies, a hypothesis that future studies can be designed to test. It also remains to be investigated whether reconstrual and repurposing offer similarly comparable benefits in other contexts.

The comparable effectiveness of reconstrual and repurposing in this context raises interesting questions about these two forms of reappraisal. We found that even though participants learned only one form of reappraisal, they reported using both strategies more often than in either control condition. This overlap might have stemmed from insufficient differentiation between the reappraisal instructions used in this study. It may also mean that the distinction between repurposing and reconstrual, although useful theoretically, is not readily accessible to lay people. Alternatively, this overlap may have stemmed from reconstrual and repurposing being mutually associated to a degree that being instructed to use one strategy primes the other strategy. Future research is needed to more directly investigate these possibilities.

After assessing results related to the primary goals, an important question was whether reducing negative emotions and increasing positive emotions in response to the pandemic might inadvertently come at the cost of decreasing intentions to engage in preventive health behaviour (reviewed in ref. 94). Reassuringly, the reappraisal interventions improved emotions without significantly reducing intentions to practice preventive health behaviours. This is consistent with recent findings that there are many paths to motivate preventive health behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic without inducing negative emotions95–98.

Our results highlight the benefits of applying reappraisal interventions at scale to increase psychological resilience and to mitigate the adverse impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic—benefits that could potentially be applied in other contexts that elicit negative emotions. Importantly, the effects of the intervention were not meagre: the extent to which emotions were changed by our reappraisal interventions was comparable in magnitude to the extent to which emotions differed between people who faced extreme hardships (lockdowns or symptom-induced isolations) and people who experienced neither of these hardships. Thus, contextualising the effect sizes of reappraisal interventions in this manner suggests that the interventions are practically meaningful. This practical meaning matters in light of findings that people on average do not appear to fully recover their emotional well-being even after six months into the COVID-19 pandemic99, that stress and depression can impair vaccine efficacy100, and that negative emotions predispose morbidity and mortality via increases in substance use and other risky behaviours101. Essential workers, nurses and doctors, students, patients and many other populations whose work and life are highly affected by the pandemic could potentially benefit from reappraisal interventions, although more research is needed to establish the effectiveness of reappraisal for groups facing distinct challenges. Because these interventions are inexpensive, brief and scalable, they could be implemented through a variety of media and communication mechanisms, such as advertising campaigns102, speeches, courses, apps and mobile games103.

Our results also have important implications for the science of emotion (reviewed in ref. 104) and for emotion regulation (reviewed in refs. 35,39) in particular. Despite the fact that reappraisal is one of the most researched topics in psychology35, this study is the largest cross-cultural investigation of reappraisal that has been conducted to date, drawing diverse samples from well beyond the WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic) societies105 that have been heavily represented to date in social science. Thus, the findings reveal the generalizability of reappraisal effects across many countries/regions even in the context of substantial, protracted stressors. The present study also extends understanding of how contextual moderators influence reappraisal processes (for example, individualism, lockdown status and demographics) while deepening understanding of distinct forms of reappraisal (that is, comparing them in relation to multiple outcomes). Finally, our study provides a rich dataset for examining many other questions related to emotions, emotion regulation and cultural differences. We look forward to seeing what other insights can be generated from this dataset.

Despite the encouraging findings, several limitations should be noted. One limitation is the use of convenience sampling and a limited set of photos. Our sample was not nationally representative within each country/region, and it appeared to over-represent females, younger people and people with internet access. The photos used in the study, although carefully chosen, might not represent local situations for different groups of participants. Future research is needed to assess generalizability using nationally representative samples and more personally emotionally evocative stimuli. A second limitation is that we cannot fully rule out the influence of demand characteristics and expectancies. Although we attempted to match demand characteristics and expectancies in the reappraisal conditions using our active control condition, we did not quantify the extent to which they were comparable, and we measured perceived strategy effectiveness after participants had used the strategies, which is different from expectancies formed upon reading the instructions but before using the strategies. Future research should assess the influence of demand characteristics and expectancies. A third limitation relates to the fact that the current study examined only the immediate and proximal effects of the interventions. Future research employing longitudinal designs is needed to examine whether the effects persist over time and at what intervals individuals might optimally engage in reappraisal. A fourth limitation is that the current study examined only a limited number of outcomes via self-report measures. More comprehensive evaluations, including assessments of actual behaviours (rather than intentions) and health outcomes, are necessary to determine whether there are any additional benefits or unintended consequences of the interventions. Finally, before implementing reappraisal interventions for practice, more research is needed to better evaluate the intervention (for example, via formal cost-benefit analysis and/or using the ‘reach, efficacy, adoption, implementation and maintenance’ framework106,107).

In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that two brief reappraisal interventions had robust and generalizable effects in reducing negative emotions and increasing positive emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic across countries/regions, without reducing intentions to practice preventive health behaviours. We hope this study will inform efforts to create scalable interventions for use around the world to build resilience during the pandemic and beyond.

Methods

Ethics information and participants.

This study is one of three studies in the PSA COVID-19 Rapid Project. The other two studies investigated the effects of loss and gain message framing and self-determination theory-guided message framing, respectively. The other two studies are reported elsewhere. The study was conducted online, and participants clicked a single data collection link that led to either the current study or the other two studies in the COVID-19 Rapid Project. A comprehensive summary of the PSA COVID-19 Rapid Project—including descriptions of the study selection procedure, the other selected studies, the internal peer review process, and implementation plans—can be found at https://psyarxiv.com/x976j/.

Participants were recruited by the PSA network. The PSA recruited 186 member laboratories from 55 countries/regions speaking 42 languages. Of the 27,989 participants recruited to complete the current study (not counting participants for the other two studies in the PSA COVID-19 Rapid Project), 4,050 were recruited through semi-representative panelling (on the basis of sex, age and sometimes ethnicity) from the following countries/regions: Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Mexico, United States, Austria, Romania, Russia, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, China, Japan and South Korea (270 participants per country/region). The remaining participants were recruited through the research groups by convenience sampling. Each research group obtained approval from their local Ethics Committee or IRB to conduct the study, explicitly indicated that their institution did not require approval for the researchers to conduct this type of task, or explicitly indicated that the current study was covered by a pre-existing approval. Although the specifics of the consent procedure differed across research groups, all participants provided informed consent. The style and the amount of compensation varied with local conventions (a common practice in PSA). More information regarding participant compensation and sample size can be found at https://psyarxiv.com/x976j/.

Procedure.

An overview of the experiment is depicted in Fig. 2.

Pre-measure.

Before reading the instructions, participants reported emotions they felt in the moment (details for all study measures are described in the next section). These ratings constituted a baseline emotional measure.

Randomization to condition.

Following the pre-measure, participants were randomly assigned to one of four between-subjects experimental conditions: two reappraisal intervention conditions (reconstrual and repurposing), one active control condition and one passive control condition. Because the study was conducted online, data collection was performed blind to the conditions of the participants. The content of the instructions in each condition differed, but the lengths were matched except for the passive control condition, which had a shorter set of instructions.

Participants in the two reappraisal intervention conditions (reconstrual and repurposing) and the active control condition received the following instructions: “In this study, we will show you photographs related to COVID-19 from various news sources. Our goal is to better understand how people respond to such photos, which may include feelings of fear, anger, and sadness. Sometimes emotions like these are helpful. At other times, however, these emotions can be unhelpful to us. Researchers have found that when people think their emotions are unhelpful, they can take steps to influence their emotions.”

In the reconstrual condition, participants were told that (emphasis in original) “One strategy that some people find helpful for influencing their emotions is rethinking. This strategy involves changing one’s thinking in order to change one’s emotions. This strategy is based on the insight that different ways of interpreting or thinking about any situation can lead to different emotions. This means that finding new ways of thinking about a situation can change how you feel about the situation. For example, consider someone who stays at home under lockdown due to COVID-19 and is feeling anxious, sad, or angry. In this case, rethinking might involve realizing that the situation is only temporary because dedicated people across the world are working hard to find a vaccine.” Participants were then given four examples of how rethinking might be employed for the COVID-19 situation (Example 1: “I know from world history that keeping calm and carrying on gets us through tough times.”; Example 2: “Scientists across the world are working hard to find treatment and vaccines. Throughout history, humans have been resourceful in finding solutions to new challenges.”; Example 3: “Washing hands, avoiding touching my face, keeping a safe distance…There are simple and effective things I can do to protect myself and my loved ones from getting sick and to stop the spread of the virus.”; Example 4: “In the past, people have overcome many challenges that seemed overwhelming at the time, and we will overcome COVID-19 related challenges too.”).

In the repurposing condition, participants were told that (emphasis in original) “One strategy that some people find helpful for influencing their emotions is refocusing. This strategy involves changing one’s thinking in order to change one’s emotions. This strategy is based on the insight that finding something good in even the most challenging situations can lead to different emotional responses. This means that refocusing on whatever good aspects may be found in a situation can change how you feel about the situation. For example, consider someone who stays at home under lockdown due to COVID-19 and is feeling anxious, sad, or angry. In this case, refocusing might involve realizing that staying at home gives them time to do things that they may not have been able to do before, like reading, painting, and spending time with family.” Participants were then given four examples of how refocusing might be employed for the COVID-19 situation (Example 1: “This situation is helping us realize the importance of meaningful social connections, and helping us understand who the most important people in our lives are.”; Example 2: “Medical systems are now learning to deal with amazing challenges, which will make them much more resilient in the future.”; Example 3: “Even though we are physically apart, we are finding creative ways to stay connected and our hearts are more connected than ever.”; Example 4: “I have been inspired by the way that frontline health care workers have responded with resilience, generosity, determination, and deep commitment.”).

In the active control condition, participants were asked to reflect on their emotions as they unfold. This condition is inspired by the literature on expressive writing and experimental disclosure, which shows that asking people to reflect about their very deepest thoughts and feelings can improve psychological health77,78. By having an active control condition, which was likely to lead to some benefit to participants, we can make stronger inferences regarding the impact of reappraisal interventions relative to a potentially useful strategy designed to equate demand characteristics and expectancies. In the instructions, participants were told that (emphasis in original) “One strategy that some people find helpful for influencing their emotions is reflecting. This strategy involves allowing oneself to freely experience and reflect on one’s thoughts and feelings. This strategy is based on the insight that reflecting on your thoughts and feelings about any situation can lead to different emotional responses. This means that exploring your thoughts and emotions can change how you feel about the situation. For example, consider someone who stays at home under lockdown due to COVID-19 and is feeling anxious, sad, or angry. In this case, reflecting might involve allowing oneself to experience these feelings and be fully immersed in the lockdown experience, reflecting on the meaning this situation has for the person and their loved ones.” Participants were then given four examples of how reflecting might be employed for the COVID-19 situation (Example 1: “This situation is changing so fast, and I don’t know how the future will develop.”; Example 2: “People are struggling to cope with these unprecedented and overwhelming challenges.”; Example 3: “Someone I love might get sick and there might not even be ventilators to help them.”; Example 4: “I really wish we could find a vaccine soon.”).

To reinforce what they had learned, participants in the two reappraisal conditions and the active control condition were then asked to summarize, in one or two sentences, the strategy they had just learned. This text response was collected only for exploratory purposes and was not used in confirmatory analysis.

In the passive control condition, participants received the following instructions: “In this study, we will show you photographs related to COVID-19 from various news sources. Our goal is to better understand how people respond to such photos, which may include feelings of fear, anger, and sadness. As you view these photographs, please respond as you naturally would.” Having a passive control condition allowed us to have clear interpretations in the case that we found no significant difference in our contrast between both the reappraisal conditions combined and both the control conditions combined. If this was the case, we would have compared each reappraisal condition against the passive control condition and compared the active control condition against the passive control condition in the exploratory analysis to determine whether each strategy had a non-zero impact relative to individuals’ natural responses.

Practice trials.

After receiving instructions by condition, participants were asked to practice the strategy in two trials designed to facilitate their understanding of the strategy. The practice trials included providing ratings and written responses to two photographs (per prior research108). The photographs in this study were selected by our research team from major media news sources (CNN, New York Times, The Guardian and Reuters) and present situations in Asia, Europe and North America. They were rated by our team to evoke either sadness or anxiety above the midpoint on a seven-point scale ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘very’ and to score close to or above the midpoint on a seven-point scale ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘very’ on the question “How much do you recommend using this picture?” (photographs available at https://osf.io/8bjnz/). In each practice trial, participants saw a ‘negative’ photo related to the COVID-19 situation (for example, an exhausted doctor or medical workers in hazmat suits) and a reminder above the photo to use the strategy that was presented to them. In the reconstrual condition, the reminder was “As you view the photo, draw on the examples we gave you earlier in order to interpret the situation in a new way.” In the repurposing condition, the reminder was “As you view the photo, draw on the examples we gave you earlier in order to focus on any good you can find in the situation.” In the active control condition, the reminder was “As you view the photo, draw on the examples we gave you earlier in order to reflect on your thoughts and feelings.” In the passive control condition, the reminder was “As you view the photo, respond as you naturally would.” After 10 s, participants were asked to rate their emotions in response to the photo using two corresponding unipolar five-point Likert scales, one for negative emotion and one for positive emotion. These ratings were designed to familiarize participants with the task, and were not used in the confirmatory analyses. After each photo, participants in the two reappraisal conditions and the active control condition were asked to write (in text) how they applied the strategy while observing the photo. Participants in the passive control condition were asked to write (in text) anything that comes naturally to their mind about the photo. The text response was also collected only for exploratory purposes and was not used in the confirmatory analysis. Participants in the two reappraisal conditions and the active control condition were then given one example of how the photo might be viewed (examples varied by condition). Note that the two reappraisal conditions and the active control condition were designed to be matched for demand characteristics and expectancy.

Experimental trials.

Following the two practice trials, participants viewed additional photos related to the COVID-19 situation in ten experimental trials. Participants in the two reappraisal conditions and the active control condition were asked to use the strategy that they practiced, and participants in the passive control condition were asked to respond naturally. All participants saw exactly the same ten photos, but the order of the presentation was randomized across the ten experimental trials. Each photo was presented to participants with the same reminder used in the practice trials. After observing each photo for ten seconds, participants were asked to rate both their negative and positive emotions in response to the photo using the same five-point Likert scales from the practice trials.

Post-measures.

In the final section of the study, participants completed several measures, including (1) negative and positive state emotions, (2) negative and positive emotions about the COVID-19 situation, (3) negative and positive anticipated emotions, (4) behavioural intentions, (5) motivation/beliefs, and (6) manipulation check.

Measures.

Demographics.

At the beginning of the study, participants completed a general survey that included demographic questions and some questions related to COVID-19 shared by all three studies in the PSA COVID-19 Rapid Project. Details about the general survey can be found at https://osf.io/7axc4/. While we originally planned for the general survey to appear at the end of the study, it was necessary for recruitment purposes (selecting representative panels) that it appear at the beginning of the study.

Baseline emotions.

To assess baseline emotion, we asked participants how they were feeling right now at the beginning of the session on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) (all response options were labelled and numbers were not displayed to participants for clarity). For negative baseline emotions, we measured five items on fear, anger, sadness, distrust and stress from the modified differential emotions scale109. For positive baseline emotions, we measured five items on hope, gratitude, love, inspiration and serenity from the modified differential emotions scale109 (details for all scoring rules are described in ‘Analysis plan’). We also measured three items on loneliness110 and three items on social connectedness111. These six items also were included in the assessment of post-photo state emotions and in the assessment of anticipated emotions (at each assessment point, these six items were used in exploratory analyses).

Negative emotional responses.

In order to capture descriptively rich, nuanced data, we measured negative emotional responses in four ways. The first way is to measure negative emotions in response to the photos. For each photo, we asked participants how negative the photo made them feel using a unipolar scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The second way is to measure negative state emotions after viewing all ten photos. We asked participants “how you are feeling right now” with the same set of items used to measure baseline emotions, which included five negative state emotions of fear, anger, sadness, distrust and stress. The third way is to measure negative emotions about the COVID-19 situation. We asked participants how negative/hopeless they were feeling about the COVID-19 situation right now on a unipolar scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The fourth way is to measure negative anticipated emotions, which were an exploratory outcome. We asked participants “In the next week, to what extent, if at all, do you think you will feel each of the following?” with the same set of items used to measure baseline emotions, which included five negative anticipated emotions of fear, anger, sadness, distrust and stress.

Positive emotional responses.

Following a parallel procedure, we measured positive emotional responses in four ways. The first way is to measure positive emotions in response to the photos. For each photo, we asked participants how positive the photo made them feel using a unipolar scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The second way is to measure positive state emotions after viewing all ten photos. We asked participants “how you are feeling right now” with the same set of items used to measure baseline emotions, which included five positive state emotions of hope, gratitude, love, inspiration, and serenity. The third way is to measure positive emotions about the COVID-19 situation. We asked participants how positive/hopeful they were feeling about the COVID-19 situation right now on a unipolar scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The fourth way is to measure positive anticipated emotions, which were an exploratory outcome. We asked participants “In the next week, to what extent, if at all, do you think you will feel each of the following?” with the same set of items used to measure baseline emotions, which included five positive anticipated emotions of hope, gratitude, love, inspiration and serenity.

Behavioural intentions.

In addition to the emotional responses that are central to our four confirmatory hypotheses in this study, we also examined exploratory outcomes concerning behavioural intentions. Such intentions matter because they have been shown to predict actual behaviours112,113. Following protocols from Fishbein and Ajzen114, we asked participants to indicate on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (extremely unlikely) to 7 (extremely likely) their intentions to engage in each of 10 different behaviours within the next week. Five of the items concern potentially harmful behaviour, which we chose based on documented links between negative emotions and substance use, aggressive behaviour and excessive information seeking17,25,115. Items included: drinking too much alcohol, using too much tobacco (for example, smoking or vaping) or other recreational drugs, yelling at someone, taking anger out online and spending too much time on media.

The other five items concerned beneficial behaviour, which we chose based on evidence that positive emotions contribute to more health behaviours84,85. Items include: eating healthy food, getting enough physical activity, practicing healthy sleep habits (for example, going to bed and waking at regular hours), washing hands regularly for at least 20 s, and following a stay-at-home order stringently (if there isn’t an order in your region now, assume that one is imposed).

Motivation and beliefs.

We measured both the motivation to use the emotion regulatory strategy and the belief in the effectiveness of the emotion regulatory strategy as exploratory moderators71,87. We asked “Recall the instructions we gave you for viewing the photos. To what extent, if at all, do you agree or disagree with the following statements?” Motivation to use the emotion regulatory strategy was measured with the item: “I tried my hardest to follow the instructions I was given while viewing the photos.” Belief in the effectiveness of the emotion regulatory strategy employed by participants was measured with the item “I believed that following the instructions would influence my emotions.” Participants rated their answers using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Manipulation check.

We planned to evaluate participants’ attention to our instructions and photos using two multiple-choice questions. The first question asked participants to choose the instructions they had at the beginning of the survey from among four options. The second question asked participants to choose the photo that was not shown to them in the survey from among three options.

For exploratory purposes, we also asked how often participants actually used each approach when viewing the photographs and their global change of emotions compared to the beginning of the study. Participants were asked, “When viewing the ten photographs related to COVID-19 earlier, how often did you use each of the following approaches?” and rated four approaches: “responding as I naturally would,” “reflecting on my thoughts and feelings,” “interpreting the situation in a new way,” and “focusing on any good I could find in the situation.” Participants rated their answers using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). To measure global change of emotion, participants were asked, “Overall, compared to the beginning of this study, how negative do you feel right now?” using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (much more negative) to 5 (much less negative) and “Overall, compared to the beginning of this study, how positive do you feel right now?” using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (much more positive) to 5 (much less positive).

Order of items.

For measures above, items belonging to the negative category (that is, negative emotional responses and intentions for harmful behaviour) and to the positive category (that is, positive emotional responses and intentions for beneficial behaviour) were presented in a counterbalanced order within each measure across participants. In other words, half of the participants always rated an item from the negative category first and then an item from the positive category, whereas the other half always rated an item from the positive category first and then an item from the negative category. For measures that have multiple items, items belonging to the negative category were randomized within the negative category, and items belonging to the positive category were randomized within the positive category. When the same set of items used to measure baseline emotions was repeated, the set had the same order for every given participant.

Analysis plan.

Pre-processing.

Exclusion.

We planned to exclude (1) participants who answered both multiple-choice manipulation check questions incorrectly, and (2) participants who completed fewer than 50% of the questions in the study.

Reliability of measures.

For items from the modified differential emotions scale109, we planned to create overall negative emotion scores at each time point by averaging the five negative emotions (fear, anger, sadness, distrust and stress) and overall positive emotion scores at each time point by averaging the five positive emotions (hope, gratitude, love, inspiration and serenity) if the average inter-item correlation was above 0.40 for negative emotions and for positive emotions, respectively. If the average inter-item correlation was below 0.40, we would conduct an exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation and maintain factors with an eigenvalue above 1.00. If no factors had an eigenvalue above 1, we would report results by item rather than as a composite. The actual average inter-item correlation was 0.50 for negative baseline emotions and 0.48 for positive baseline emotions. Therefore, we created overall negative emotion scores at each time point by averaging the five negative emotions and overall positive emotion scores at each time point by averaging the five positive emotions.

Missing data.

We dropped incomplete cases on an analysis-by-analysis basis. Given our sampling plan described below, we should have power of 0.95 or above.

Outliers.

In order to be maximally conservative, we did not define or identify outliers.

Analytic plan for hypotheses.

Since negative emotional responses and positive emotional responses are separable79,80, we examined negative emotional responses and positive emotional responses separately. To control family-wise error rates in multiple comparisons, we used the Holm–Bonferroni method within each of the four hypotheses separately. For all analyses testing negative emotional responses (hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 3), we planned to control for the participants’ negative baseline emotions. As originally intended by the scale109, we planned to create an overall negative baseline emotion score by averaging the five negative emotions (fear, anger, sadness, distrust and stress). For all analyses testing positive emotional responses (hypothesis 2 and hypothesis 4), we planned to control for the participants’ positive baseline emotions. As originally intended by the scale109, we planned to create an overall positive baseline emotion score by averaging the five positive emotions (hope, gratitude, love, inspiration and serenity). To account for the nested structure in our data (for example, participant nested by country/region), we fitted multilevel models with the condition using the contrast in Table 1, random by-country/region slopes, and random by-country/region intercepts. If a model failed to converge, we planned to explore other reasonable models113 and report results of all explored models in an appendix. We visually assessed assumptions of heteroscedasticity and normality of residuals and found no severe deviations. All tests were two-tailed.