Abstract

Background:

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is one of the most common spinal deformities in children and adolescents requiring extensive surgical intervention. Due to the nature of surgery, spinal fusion increases their risk of experiencing persistent postsurgical pain. Up to 20% of adolescents report pain for months or years after corrective spinal fusion surgery.

Aims:

To examine the influence of preoperative psychosocial factors and mRNA expression profiles on persistent postoperative pain in adolescents undergoing corrective spinal fusion surgery.

Design:

Prospective, longitudinal cohort study.

Setting:

Two freestanding academic children’s hospitals.

Methods:

Utilizing a longitudinal approach, adolescents were evaluated at baseline (preoperatively) and postoperatively at ±1 month and ±4-6 months. Self-report of pain scores, the Pain Catastrophizing Scale-Child, and whole blood for RNA sequencing analysis were obtained at each time point.

Results:

Of the adolescents enrolled in the study, 36% experienced persistent pain at final postoperative follow-up. The most significant predictors of persistent pain included preoperative pain severity and helplessness. Gene expression analysis identified HLA-DRB3 as having increased expression in children who experienced persistent pain postoperatively, as opposed to those whose pain resolved. A prospective validation study with a larger sample size is needed to confirm these findings.

Conclusions:

While adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is not often classified as a painful condition, providers must be cognizant of pre-existing pain and anxiety that may precipitate a negative recovery trajectory. Policy and practice change are essential for early identification and subsequent intervention.

Each year, six million children and adolescents will undergo surgery and are at risk of experiencing persistent postsurgical pain (PPP), defined as pain at or around the surgical region (incision and surrounding tissue) that lasts ≥8 weeks postoperatively (Katz & Seltzer, 2009; Macrae, 2001; Manworren et al., 2015). PPP significantly impairs quality of life and increases vulnerability for later comorbid persistent pain disorders (Nikolajsen & Brix, 2014). Corrective spinal fusion (SF) surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is one of the most invasive surgical procedures performed on adolescents and may result in PPP that can last for years, impairing physical and social functioning (Rullander et al., 2013). To date, the most significant risk factor identified for PPP after AIS corrective surgery is the severity of presurgical pain (Walker, 2015). Based on research findings in other pain populations, both psychological factors (anxiety, depressive symptoms, pain catastrophizing) and social factors (self-image, peer relationships) can increase the risk of PPP (Edwards et al., 2009; Starkweather & Pair, 2013). In addition, genetic predisposition may play a role in transition to PPP in adolescents; however, few studies have simultaneously examined these biopsychosocial risk factors. Identification of the factors that precipitate PPP in adolescents with AIS could lead to the development of innovative personalized approaches for pain management throughout the perioperative course, with the goal of reducing the incidence of PPP, improving pain outcomes, and protecting quality of life.

To further examine the biological and psychosocial risk factors of PPP in adolescents undergoing SF, the authors conducted a prospective, descriptive longitudinal study. The present study aimed to identify preoperative psychosocial factors and mRNA expression profiles predictive of PPP among adolescents undergoing corrective spinal fusion surgery. We hypothesized that adolescents who experience PPP will experience higher levels of pain severity and pain catastrophizing throughout the perioperative period, and that variability in PPP is further associated with one or more differential gene expression profiles.

Materials and Methods

Design

The study used a prospective, descriptive, longitudinal design. Data collection time points included preoperative (baseline) and postoperative (±1-month, ±4-6 months).

Sample and Setting

The study included 36 adolescents who underwent SF after AIS diagnosis. Data collection occurred at two freestanding children’s hospitals. Institutional Review Board approval from each site was obtained prior to data collection. The parents of all eligible children and adolescents were approached and provided informed consent. Additionally all eligible children and adolescents were approached to provide assent for participation.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) men and women between the ages of 10 and 17 years old at the time of surgery; (2) history of AIS and scheduled for SF surgery; (3) cognitively intact, as evidenced by ability to follow simple instructions, provide a self-report of pain, and assent for the procedure and study; (4) able to read, write and speak English. Exclusionary criteria included: (1) diagnosed chronic pain conditions and (2) conditions involving impairment or loss of sensation.

Measures

Biological Factors

Age, sex, and race/ethnicity were obtained via electronic medical record and verified by self-report from the patient or family member.

Pain Intensity

Adolescents were asked to complete a visual analog scale (VAS). Using a past seven-day recall, adolescents were asked to self-report their pain scores on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). The VAS is a self-report scale of pain intensity that is valid for use in children without cognitive impairment. A comprehensive review of pediatric pain scaled by Cohen et al. (2008) reports good inter-rater reliability amongst studies (r = 0.28-0.72), with concurrent validity (r = 0.61-0.9) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.41-0.58) of the VAS in pediatric populations.

Psychosocial Factors

Pain catastrophizing was measured using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale-Child (PCS-C), a 13-item self-report measure that assesses children’s thoughts and emotions in response to pain (Crombez et al., 2003). Similar to the original, adult-specific PCS (Sullivan et al., 2001), the PCS-C items are rated on a five-point scale yielding a maximum possible score of 52 with three subscales scores: rumination, magnification, and helplessness. Higher scores indicate higher levels of catastrophizing or rumination, magnification, or helplessness regarding pain. The PCS-C showed good internal consistency (α = .87-.90) in schoolchildren with and without pain, and correlated highly with pain intensity (r = 0.49) and disability (r = 0.50) in children with chronic pain (Crombez et al., 2003). The PCS-C has been used in other pediatric surgical studies (Esteve, et al., 2014; Page et al., 2012).

Gene Expression

Differential gene expression was measured in whole blood preoperatively, collected via venipuncture into one 5-mL cell preparation tube with sodium citrate (PAXgene Blood RNA tube). RNA isolation was performed via one of two RNA extraction methods. Samples were extracted using the PAXgene total RNA isolation system (PreAnalytiX, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The integrity of the total RNA was assayed on the Agilent TapeStation 2200 (Santa Clara, CA) and RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) were obtained for each sample. Only samples with RIN numbers of ≥6.4 were included in sequencing. Total RNA was pooled and transported to Macrogen USA (Rockville, MD) for sequencing using NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) pairedend, high-throughput sequencing.

Data Analysis

Two groups were delineated among the 36 adolescents who were recruited: those who transitioned to PPP (≥2 on VAS at final appointment) and those without PPP (<2 on VAS at final appointment). This cutoff value is consistent with previous studies of low back pain within the University of Connecticut Center for the Advancement of Managing Pain (Baumbauer et al., 2020; Starkweather et al., 2016). Psychosocial data were analyzed using SPSS Statistical Package v25 (IBM Corp., 2017), while genetic data were analyzed within the RStudio v.1.1.456 environment (2015). Preliminary analysis was conducted to look for missing data and assess the reliability of all research instruments used. Descriptive statistics (means and standard errors for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables) were used to characterize the study sample. Between-group differences were assessed via independent sample t tests to detect a main effect on the dependent variable (PPP) and linear regression.

Raw data via fastq files (text files containing raw sequence data) were received and uploaded to a high-performance computing system. A prescribed RNA sequencing pipeline outlined per the University of Connecticut’s Computational Biology Core was followed. This sequencing pipeline included the following computational packages: FastQC v.0.11.7 (Andrews, 2010), MultiQC v.1.6 (Ewels et al., 2016), Trimmomatic 0.27 (Bolger et al., 2014), HISAT2 v. 2.1.0 (Kim, et al., 2015), SAMtools v.1.7 (Li et al., 2009), HTSeq v.0.11.0 (Anders et al., 2015), and DESEQ2 (Love et al., 2014). RNA segments were mapped to the reference human genome: GRCh38.p12 (Zerbino et al., 2017). Using DESeq2’s software independent sample t tests and Wald tests to adjust for log-fold change. Genes were determined to be differentially expressed if adjusted p value was ≤.05. False discovery rate was set to 0.1 to account for the multiple comparisons generated throughout the analysis where traditional Bonferroni corrections are too conservative.

Results

Sample Demographics

Of the 36 adolescents enrolled in the study, 13 (36%) reported a pain rating of ≥2 at their final follow-up appointment and were classified as transitioning to PPP. Analysis revealed no significant differences in demographics between the PPP vs. non-PPP groups. Age, sex, and race were not associated with persistent pain outcomes (p = .46, p = .391, and p = .43, respectively). Table 1 outlines demographics and corresponding pain intensity scores.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Pain Intensity Scores

| All Individuals (N = 36) | Non-PPP (n = 23) | PPP (n = 13) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 14 (1.75) | 13.9 (1.56) | 14.3 (2.06) |

| Sex | |||

| Female (%) | 27 (75%) | 16 (30.4%) | 11 (84.6%) |

| Male (%) | 9 (25%) | 7 (69.6%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Race | |||

| White | 21 (58.3%) | 12 (52.2%) | 9 (69.2%) |

| Black | 4 (11.1%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Asian | 2 (5.6%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other/Missing | 9 (25%) | 7 (30.4%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Numeric Pain Scores (Self-Report) | |||

| Baseline (SD) | 2.25 (2.51) | 1.35 (2.26) | 3.85 (2.51) |

SD = standard deviation.

Pain Intensity

Results of the independent samples t-test indicated that pain intensity differed between the PPP vs. non-PPP groups at each time point (Table 1). There was a significant difference in reported preoperative pain scores between the PPP (3.85 ± 2.51) vs. non-PPP groups (1.35 ± 2.26); t (28) = −2.49, p = .008). A logistic regression was performed to evaluate the association between preoperative self-report of pain and likelihood of PPP incidence. The model explained 28% (Nagelkereke R2) of the variance in PPP status and correctly classified 73.3% of cases. Increased preoperative pain was associated with 1.5x higher incidence of PPP (p = .02).

Pain Catastrophizing

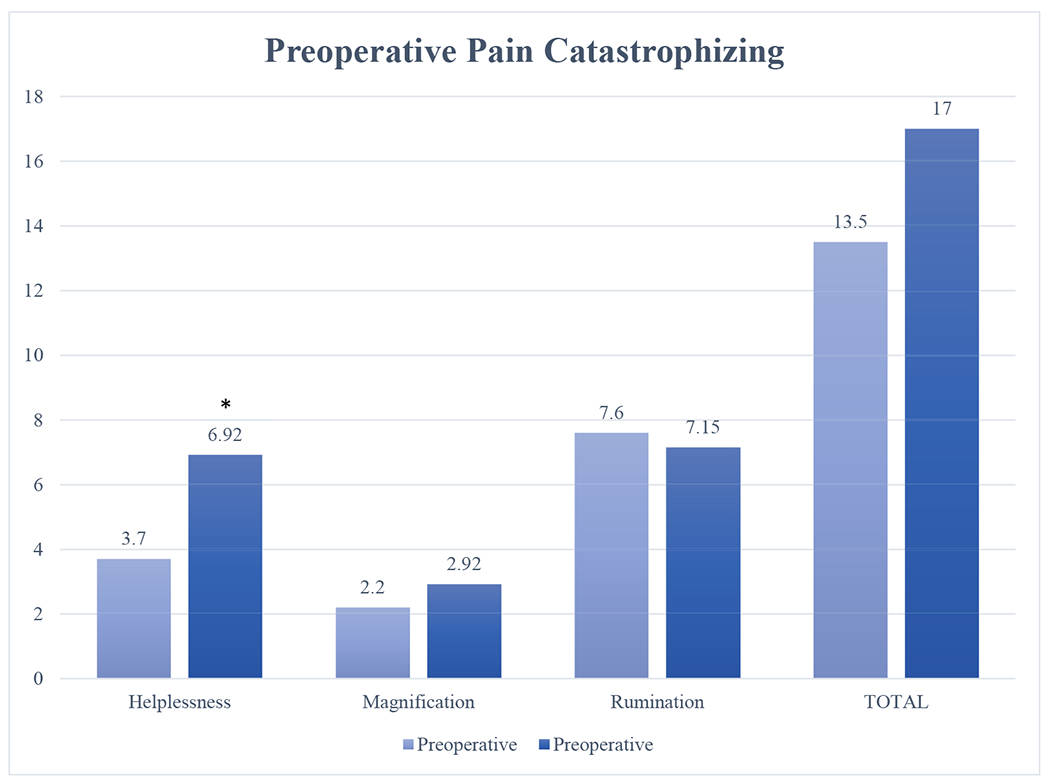

Figure 1 outlines pain catastrophizing subscale and total scores preoperatively. Independent samples t test demonstrated that at the preoperative appointment, the helplessness subscale was significantly higher in the PPP vs. non-PPP groups (t[31] = −2.47, p = .02; mean difference 3.22). Logistic regression was performed to evaluate the association between preoperative subscale scores and total PCS scores on the likelihood of PPP. The model explained 41% (Nagelkereke R2) of the variance in PPP status and correctly classified 75.8% of cases. Increased preoperative helplessness was associated with 1.6 × higher incidence of PPP (p = .01), whereas increased rumination was associated with a 0.68 × decrease of PPP incidence (p = .034).

Figure 1.

Preoperative pain catastrophizing. * <0.05. Pain catastrophizing and its subscales were assessed preoperatively via the pediatric Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS). Mean PCS subscale and total scores are presented. Preoperative helplessness had a significant mean difference in those retrospectively classified as experiencing persistent postoperative pain at their final ±4-month appointment; p = .02.

Transcript Characterization: PPP vs. Non-PPP

Of the biological samples obtained, 15 were deemed viable in terms of integrity and quality. Across all samples (N = 15), average mapping reached 98.84% of the reference genome. In total, 66,023 gene transcripts were assessed. Between-group comparisons were made to determine differential gene expression of those in the PPP (n = 6) vs. non-PPP (n = 9) group. Preoperatively, HLA-DRB3 (p = .04) expression was significantly higher in PPP individuals compared to non-PPP (Log2FC 8.81).

Discussion

This study sought to identify biopsychosocial contextual factors that may increase incidence of PPP after SF surgery. The demographics of the sample were consistent with the wider population of adolescents with AIS. Our sample was primarily composed of non-Hispanic White women. According to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (2017), women are 8 times more likely to have a curvature requiring treatment. In terms of the prevalence of PPP in this population, Rabbitts et al. (2017) reported that up to 20% of adolescents experience PPP after AIS corrective surgery, which is consistent with our findings of PPP in 36% of our small sample.

Pain intensity scores were higher in the PPP group compared with the non-PPP group at each of the three prescribed timepoints across the perioperative period. Of note, adolescents in the PPP group had significantly higher preoperative pain intensity scores compared to the non-PPP group. Additionally, preoperative pain intensity scores were found to be predictive of PPP incidence. Similar findings regarding the relationship between preoperative pain scores and risk for PPP have been discussed in a recent integrative review of the literature (Perry et al., 2018). Early recognition of pain by healthcare providers in the preoperative period is thus imperative to improving postsurgical pain outcomes. Interestingly, however, the literature presents conflicting results as to whether or not AIS itself is a painful condition that should be evaluated preoperatively. A recent systematic review reports that while back pain in adolescents is common, the incidence of comorbid pain with AIS is relatively low, with an inconsistent and weak correlation between biomechanical issues of scoliosis and pain (Balagué & Pellisé, 2016).

This consensus regarding pain is also agreed upon by the Scoliosis Research Society (SRS), who states within their parental education portal that patients with AIS typically have no pain (2019). The SRS goes on to add that while lower back pain may be reported, this is generally due not to spine curvature, but to participation in athletic events without the support of proper core muscles, back strength, or hamstring flexibility (2019). Contrarily, a retrospective chart review of adolescents with AIS reports that nearly half of patients experience back pain (47.3%), with lumbar pain cited as the most painful area (22.6%; Théroux et al., 2015). Although presence of pain was documented, pain intensity was charted in only 21% of patient records, and there was no prescribed pain management plan in 80% of patient charts (Théroux et al., 2015). Other studies investigating pain in AIS report that back pain is an accompanying characteristic and may affect up to 71% of adolescents diagnosed with AIS (Makino et al., 2015; Smorgick et al., 2013). This finding is much higher than what has been previously reported in the past.

The findings within the literature, paired with our results, raise questions regarding whether or not this reported preoperative pain is undiagnosed chronic pain that is eventually coined persistent in the postoperative period. Consistent with previous research, our findings demonstrate that children and adolescents who experience pain preoperatively often continue to have pain within the postoperative period. A more in-depth analysis with a larger sample size must be conducted to establish whether the pain experienced within this current study postoperatively is in fact unique PPP, or is chronic preoperative pain carried into the postoperative period.

As such, policy and practice changes related to preoperative pain assessment are crucial for early identification and intervention within this population. Scoliosis screening in primary and secondary schools is currently heavily debated (Dunn et al., 2018; Jakubowski & Alexy, 2014; Linker, 2012). A position statement by the SRS, American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS), Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America (POSNA), and Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advocates for scoliosis screening, as it leads to beneficial early detection and non-surgical treatment options for AIS (Hresko, et al., 2016). Despite this position statement, fewer than half of American states have legislation that recommends or requires scoliosis screening in primary or secondary schools (Grivas et al., 2007). When mandated or recommended, screening is often performed by the school nurse. Considering that preoperative pain is a risk factor for PPP after corrective surgery, it would be prudent for school nurses to perform a focused pain assessment at the time of screening. A recent study evaluating school nurse pain documentation reveals an overall lack of pain assessment, with less than 1% of school-aged children having documented pain scores and no valid age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate scales documented (Quinn et al., 2019). In an effort to standardize scoliosis screening in states with legislation, many government agencies provide screening guidelines to school nurses. Though helpful for identifying degree of deformity, these guidelines vary by state in regard to pain assessment. While some states, such as New York, suggest a focused pain assessment at the time of screening (The University of the State of New York, State Education Department & Office of Student Support Services, 2018), others do not (e.g., Alabama, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah; State of Connecticut, 2018; Alabama State Board of Education, 2007; Utah Department of Health, 2017; State of Pennsylvania, 2019; Texas Department of State Health Services, 2019). Although school nurses are well-versed and proficient in assessing for spinal deformity, emphasis should also be placed on pain assessment at the time of screening using age and developmentally appropriate tools.

Additionally, within our cohort, evidence of continued persistent pain postoperatively may indicate minimal relief after SF surgery. This finding contrasts with those of a recent study examining pain scores measured by the SRS-22r after SF for AIS. The SRS-22r created by Scoliosis Research Pain Society is a 22-item questionnaire that assesses patient-reported outcomes of scoliosis, intervention including, function, pain, self-image, and mental health (Asher et al., 2003). This study finds evidence that AIS may be considered a painful condition, but concludes that SF surgery improved SRS-22r pain scores 2 years postoperatively (p < .000) and achieved mean clinically important differences for SRS pain thresholds (Djurasovic et al., 2018). A larger sample size with increased window for follow-up may be necessary to validate these findings within our cohort.

In regard to psychosocial functioning, pain catastrophizing scores were higher at each time point in the PPP group, with the exception of rumination, compared to those who had normal resolution of pain. However, the most sensitive indicator of persistent pain incidence was preoperative helplessness. Considering that preoperative pain is a significant indicator of PPP transition within this sample, preoperative assessment should rely not only on subjective pain scores, but also on an individual’s well-being and mental status. In line with our findings, a study conducted by Noel et al. (2015) reported that perioperative helplessness was the only correlative factor to a child’s pain-related emotional wellness several weeks postoperatively. Targeted assessment surrounding helplessness characteristics may therefore be useful in understanding who may be at an increased risk of PPP throughout the perioperative period. From this understanding, the development of personalized interventions for reducing helplessness throughout the perioperative period may be used to reduce the risk of PPP and improve postoperative outcomes. Interestingly, increased preoperative rumination was negatively associated with PPP incidence in our small cohort. A possible explanation could be that those who participated in our study were otherwise healthy adolescents. Preoperative rumination may be related to anticipation of pain associated with the surgical procedure, as opposed to actual pain. Asking children about their pain during an anxiety-provoking time, such as preoperative SF appointment, may precipitate rumination regardless of pain status (pre-existing or not). A recent study by Kokoneyei et al. (2019) closely examined the associations between trait rumination and anticipatory pain processing in healthy subjects. This study demonstrated increased neural response assessed via functional magnetic resonance imaging in a cohort of 30 healthy subjects in response to anticipated experimental pain. An in-depth analysis of the context of rumination within a larger AIS preoperative cohort is necessary to validate our results.

Analysis of RNA-sequencing data demonstrated significantly higher expression of HLA-DRB3, an HLA complex and chemokine signaling molecule, in the preoperative period compared to the non-PPP group (Parisien et al., 2017). Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex is a gene complex that encodes for the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), an essential component of immunity. This protein-rich complex is positioned on the surface of cells, where it is able to determine histocompatibility of foreign bodies within the system. It is present in antigen-presenting cells (APC), macrophages, and so on, which present for CD4+ recognition (UniProt Consortium, 2017). Although not definitive, these findings may suggest that increased expression of HLA-DRB3 before the surgical insult may be a useful biomarker in identification of those with increased propensity for immune-related pain persistence. Further investigation is necessary to substantiate these claims. Several studies investigating genes within the HLA region have demonstrated involvement of the HLA region in multiple chronic pain states, such as the role of increased HLA-B27 antigen in chronic low back pain diagnosis, increased HLA-DQ8 in chronic regional pain syndrome, and increased HLA-DRB1 in migraine headaches (Jajiæ, 1979; Rainero et al., 2005; van Rooijen et al., 2012). Involvement of the HLA haplotype in chronic postsurgical pain in hernia repair surgery and lumbar disc herniation has also been documented (Dominguez et al., 2013). Uncovering the underlying mechanisms of PPP transition may aid in understanding the innate immune response to surgical procedures. However, further research and validation of these particular immunity-related genes are necessary to understand their possible role in pain modulation and postoperative chronic pain.

Limitations

Although this study generated important preliminary results regarding the biopsychosocial factors associated with PPP post-SF surgery, there were limitations that require cautious interpretation and replication in future studies. The major limitation was the small sample size, specifically for the genetic analysis, which limited the ability to evaluate covariates such as sex, race and ethnicity. Much of this is due in part to recruitment and retention within this unique population. Similar challenges being reported in previous studies focused on children undergoing surgery (Noel et al., 2015). For the genetic analysis, the read alignment and sequencing pipeline provided an in-depth analysis regarding risk reduction of type I and type II errors. However, recommendations for larger sample sizes are imperative for generalizing these results to the larger populations, and the current study results should thus be interpreted cautiously (Baccarella et al., 2018).

In addition to small sample size, validation via Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) was not feasible for this study due to limited access to additional control samples. Studies investigating the usefulness of qPCR as a validation step suggest that validation should occur against a separate cohort. Future studies using a validation step may strengthen the transferability of the RNA sequencing results throughout various populations.

Conclusion

The findings of this study add to the growing knowledge of biopsychosocial factors that may increase the risk of persistent pain in children and adolescents undergoing AIS corrective surgery, particularly the role of preoperative pain intensity scores, helplessness, and potential immunity-mediated biomarkers on one’s recovery trajectory. Readily identifiable and modifiable risk factors such as preoperative pain and catastrophizing may be useful in early identification and subsequent intervention, such as patient and family education. School nurses and other school-based healthcare professionals are well positioned to identify preoperative pain and catastrophizing prior to children and adolescents presenting at an orthopedic clinic. If school-based scoliosis screening is recommended or required by state legislation, policy and practice change to include age and developmentally focused pain assessments at the time of screening is suggested.

Although the findings from our gene expression data are interesting, it is important to note that they are preliminary. These findings warrant further investigation in a larger sample and clinical validation before integration in practice. In the future, such measures may become part of personalized pain management strategies for children and adolescents undergoing surgical procedures. The overall goal of individualized pain management is early identification of risk factors of persistent pain in order to improve postoperative function, quality of life, and recovery for the thousands of children and adolescents undergoing surgery each year.

Sources of Funding

M. Perry has received financial support from the Jonas Center for Nursing Excellence, the Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need (GAANN) Fellowship, the International Society of Nurses in Genetics (ISONG), the Center for the Advancement of Nursing Sciences (CANS)/Eastern Nursing Research Society (ENRS) Dissertation Award, and University of Connecticut’s Center for the Advancement of Managing Pain (CAMP).

In addition, C. Sieberg has been award a funding mechanism (K23GM123372) support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) and a Career Development Award from the Office of Faculty Development at Boston Children’s Hospital, which has aided in the culmination of this work.

References

- Alabama State Board of Education. (2007). Spinal screening program: Procedure manual. Retrieved from https://www.alsde.edu/sec/pss/Health%20Screenings/ALABAMA%20PUBLIC%20SCHOOL%20SPINAL%20SCREENING%20MANUAL%20(2007%20VERSION).pdf. (Accessed 27 March 2020).

- American Association of Neurological Surgeons. (2017). Scoliosis. Retrieved from https://www.aans.org/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Scoliosis. (Accessed 12 June 2017).

- Anders S, Pyl PT, & Huber W (2015). HTSeq: A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics, 31(2), 166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S (2010). FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Retrieved from http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc. (Accessed 19 May 2018).

- Asher M, Min Lai S, Burton D, & Manna B (2003). Scoliosis research society-22 patient questionnaire: Responsiveness to change associated with surgical treatment. Spine, 28(1), 70–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccarella A, Williams CR, Parrish JZ, & Kim CC (2018). Empirical assessment of the impact of sample number and read depth on RNA-Seq analysis workflow performance. BMC Bioinformatics, 19(1), 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagué F, & Pellisé F (2016). Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and back pain. Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders, 11(1), 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumbauer K, Ramesh D, Perry M, Carney KB, Julian T, Glidden N, Dorsey SG, & Starkweather AR (2020). Contribution of COMT and BDNF genotype and expression to the risk of transition from acute to chronic low back pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. Publish Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, & Usadel B (2014). Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics, 30(15), 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombez G, Bijttebier P, Eccleston C, Mascagni T, Mertens G, Goubert L, & Verstraeten K (2003). The child version of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS-C): A preliminary validation. Pain, 104(3), 639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LL, Lemanek K, Blount RL, Dahlquist LM, Lim CS, Palermo TM, McKenna KD, & Weiss KE (2008). Evidence-based assessment of pediatric pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(9), 939–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djurasovic M, Glassman SD, Sucato DJ, Lenke LG, Crawford CHI, & Carreon LY (2018). Improvement in Scoliosis Research Society-22R pain scores after surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 43(2), 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez CA, Kalliomaki M, Gunnarsson U, Moen A, Sandblom G, Kockum I, Lavant E, Olsson T, Nyberg F, Rygh LJ, Roe C, Gjerstad J, Gordh T, & Piehl F (2013). The DQB1 *03:02 HLA haplotype is associated with increased risk of chronic pain after inguinal hernia surgery and lumbar disc herniation. Pain, 154(3), 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, Nguyen M, Blasi PR, & Lin JS (2018). Screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. In Evidence Synthesis, No. 156. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Campbell C, Jamison RN, & Wiech K (2009). The neurobiological underpinnings of coping with pain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(4), 237–24 . [Google Scholar]

- Esteve R, Marquina-Aponte V, & Ramirez-Maestre C (2014). Postoperative pain in children: Association between anxiety sensitivity, pain catastrophizing, and female caregivers’ responses to children’s pain. Journal of Pain, 15(2), 157–168.e151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewels P, Magnusson M, Kaller M, & Lundin S (2016). MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics, 32(19), 3047–3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivas TB, Wade MH, Negrini S, O’Brien JP, Maruyama T, Hawes MC, Rigo M, Weiss HR, Kotwicki T, Vasiliadis ES, Sulam LN, & Neuhous T (2007). SOSORT consensus paper: School screening for scoliosis. Where are we today? Scoliosis, 2, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hresko MT, Talwalkar V, Schwend R, AAOS SRS, & POSNA. (2016). Early detection of idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 98(16), e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25). Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jajiæ I (1979). The role of HLA-B27 in the diagnosis of low back pain. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, 50(4), 411–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski TL, & Alexy EM (2014). Does school scoliosis screening make the grade? NASN School Nurse, 29(5), 258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, & Seltzer Z (2009). Transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain: Risk factors and protective factors. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 9(5), 723–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Langmead B, & Salzberg SL (2015). HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nature Methods, 12(4), 357–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokonyei G, Galambos A, Edes AE, Kocsel N, Szabo E, Pap D, Kozak LR, Bagdy G, & Juhasz G (2019). Anticipation and violated expectation of pain are influenced by trait rumination: An fMRI study. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 19(1), 56–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, & 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics, 25(16), 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linker B (2012). A dangerous curve: The role of history in America’s scoliosis screening programs. American Journal of Public Health, 102(4), 606–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, & Anders S (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq with DESeq2. Genome Biology, 14(12), 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae WA (2001). Chronic pain after surgery. BjA: International Journal of Anaesthesia, 87(1), 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino T, Kaito T, Kashii M, Iwasaki M, & Yoshikawa H (2015). Low back pain and patient-reported QOL outcomes in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis without corrective surgery. Springerplus, 4, 397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manworren RC, Ruano G, Young E, St Marie B, & McGrath JM (2015). Translating the human genome to manage pediatric postoperative pain. Journal of Pediatric Surgical Nursing, 4(1), 28–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolajsen L, & Brix LD (2014). Chronic pain after surgery in children. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 27(5), 507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel M, Rabbitts JA, Tai GG, & Palermo TM (2015). Remembering pain after surgery: A longitudinal examination of the role of pain catastrophizing in children’s and parents’ recall. Pain, 156(5), 800–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MG, Stinson J, Campbell F, Isaac L, & Katz J (2012). Pain-related psychological correlates of pediatric acute post-surgical pain. Journal of Pain Research, 5, 547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisien M, Khoury S, Chabot-Doré AJ, Sotocinal SG, Slade GD, Smith SB, Fillingim RB, Greenspan JD, Maixnver W, Mogil JS, Belfer I, & Diatchenko L (2017). Effect ofhuman genetic gariability on gene expression in dorsal root ganglia and association with pain phenotypes. Cell Reports, 19(9), 1940–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M, Starkweather A, Baumbauer K, & Young E (2018). Factors leading to persistent postsurgical pain in adolescents undergoing spinal fusion surgery: An integrative literature review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 38, 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn BL, Lee SE, Bhagat J, Holman DW, Keeler EA, & Rogal M (2019). A retrospective review of school nurse approaches to assessing pain. Pain Management Nursing, 21 (3), 233–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitts JA, Fisher E, Rosenbloom BN, & Palermo TM (2017). Prevalence and predictors of chronic postsurgical pain in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pain, 18(6), 605–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainero I, Fasano E, Rubino E, Rivoiro C, Valfrè W, Gallone S, Savi L, Gentile S, Lo Guidice R, De Martino P, Dall’Omo AM, & Pinessi L (2005). Association between migraine and HLA—DRB1 gene polymorphisms. Journal of Headache Pain, 6(4), 185–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rullander A, Jonsson H, Lundstrom M, & Lindh V (2013). Young people’s experiences with scolisos surgery: a survey of pain, nausea, and global satisfaction. Orthopedic Nursing, 32(6), 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoliosis Research Society. (2019). Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Retrieved from https://www.srs.org/patients-and-families/conditions-and-treatments/parents/scoliosis/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis. (Accessed 9 January 2019).

- Smorgick Y, Mirovsky Y, Baker KC, Gelfer Y, Avisar E, & Anekstein Y (2013). Predictors of back pain in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis surgical candidates. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics, 33(3), 289–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkweather AR, & Pair VE (2013). Decoding the role of epigenetics and genomics in pain management. Pain Management Nursing, 14(4), 358–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkweather AR, Ramesh D, Lyon DE, Siangphoe U, Deng X, Sturgill J, Heineman A, Elswick RK Jr., Dorsey SG, & Greenspan J (2016). Acute low back pain: Differential somatosensory function and gene expression compared with healthy no-pain controls. Clinical Journal of Pain, 32(11), 933–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of Connecticut. (2018). Draft guidelines for health screenings: Vision, hearing and scoliosis. Retrieved from https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/SDE/Special-Education/Guidelines_Health_Screenings_CSDE.pdf. (Accessed 23 March 2020).

- State of Pennsylvania. (2019). Procedure for conducting scoliosis screening. Retrieved from https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/Documents/School%20Health/Scoliosis%20Guidelines%202019.pdf. (Accessed 23 March 2020).

- Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, & Lefebvre JC (2001). Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clinical Journal of Pain, 17(1), 52–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. (2015). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Texas Department of State and Health Services. (2019). Spinal screening program guidelines. Retrieved from https://dshs.texas.gov/spinal/spinalguide.shtm. (Accessed 23 March 2020).

- The Univesity of the State of New York, State Education Department & Office of Student Support Services. (2018). Scoliosis screening guidelines for schools. New York. Retrieved from http://www.p12.nysed.gov/sss/documents/ScoliosisScreeningGuidelinesFINALApril2018.pdf. (Accessed 24 March 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Théroux J, Le May S, Fortin C, & Labelle H (2015). Prevalence and management of back pain in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients: A retrospective study. Pain Research & Management, 20(3), 153–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProt Consortium. (2017). UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(D1), D158–D169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utah Department of Health. (2017). Utah school spinal (Scoliosis) screening guidelines. Retrieved from https://choosehealth.utah.gov/documents/pdfs/school-nurses/Final_Scoliosis_Guidelines.pdf Accessed March 2020.

- van Rooijen DE, Roelen DL, Verduijn W, Haasnoot GW, Huygen FJ, Perez RS, Claas FH, Marinus J, van Hilten JJ, & van den Maagdenberg AM (2012). Genetic HLA associations in complex regional pain syndrome with and without dystonia. Journal of Pain, 13(8), 784–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SM (2015). Pain after surgery in children: Clinical recommendations. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 28(5), 570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino DR, Achuthan P, Akanni W, Amode MR, Barrell D, Bhai J, Billis K, Cummins Gall, A., Girocn CG, Gil L, Gordon L, Haggerty L, Haskell E, Hourlier T, Izuogu OG, Janacek SH, Juettemann T, To JK, Laird MR, Lavidas I, Liu Z, Loveland JE, Maurel T, McLaren W, Moore B, Mudge J, Murphy DN, Newman V, Nuhn M, Ogeh D, Ong CK, Parker A, Patricio M, Riat HS, Schuilenburg H, Sheppard D, Sparrow H, Taylor K, Thormann A, Vullo A, Walts B, Zadissa A, Frankish A, Hunt SE, Kostadima M, Langridge N, Martin FJ, Muffato M, Perry E, Ruffier M, Staines DM, Trevanion SJ, Aken BL, Cunningham F, Yates A, & Flicek P (2018). Ensembl 2018. NucleicAcids Research, 46(D1), D754–D761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]