Abstract

Aims

To develop a suite of quality indicators (QIs) for the evaluation of the care and outcomes for adults undergoing cardiac pacing.

Methods and results

Under the auspice of the Clinical Practice Guideline Quality Indicator Committee of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the Working Group for cardiac pacing QIs was formed. The Group comprised Task Force members of the 2021 ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy, members of the European Heart Rhythm Association, international cardiac device experts, and patient representatives. We followed the ESC methodology for QI development, which involved (i) the identification of the key domains of care by constructing a conceptual framework of the management of patients receiving cardiac pacing, (ii) the development of candidate QIs by conducting a systematic review of the literature, (iii) the selection of the final set of QIs using a modified-Delphi method, and (iv) the evaluation of the feasibility of the developed QIs. Four domains of care were identified: (i) structural framework, (ii) patient assessment, (iii) pacing strategy, and (iv) clinical outcomes. In total, seven main and four secondary QIs were selected across these domains and were embedded within the 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization therapy.

Conclusion

By way of a standardized process, 11 QIs for cardiac pacing were developed. These indicators may be used to quantify adherence to guideline-recommended clinical practice and have the potential to improve the care and outcomes of patients receiving cardiac pacemakers.

Keywords: Cardiac pacemaker, Quality indicators, Clinical practice guidelines

What’s new?

Collaborative effort between international experts in cardiac devices and patients using the European Society of Cardiology methodology for quality indicator development.

A set of quality indicators has been constructed for the quantification of cardiac pacing care quality and outcomes.

Eleven quality indicators have been developed across four domains of pacing care: (i) structural framework, (ii) patient assessment, (iii) pacing strategy, and (iv) clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Cardiac pacing is frequently used to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with cardiac rhythm disturbances.1 Expanding pacing indications, an ageing population and an increased life expectancy have led to increasing pacemaker implantation rates in recent years.2,3 Even so, large variations in the rates of implantation and associated complications has been observed within and between countries.3,4 According to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Cardiovascular Disease Statistics, in 2018/19 age- and sex-standardized implantation rates ranged from <60 to >1000 pacemakers per million people across ESC member countries.5 Clinical registries provide an opportunity to capture real-world naturalistic data on cardiac pacing to better understand variations and gaps in practice.4,6 However, there is a need to develop and standardize the tools by which the quality of care for cardiac pacing is evaluated and resultant outcomes monitored and reported. Such tools may integrate with, and provide, the means to develop clinical registries for cardiac pacing, as well as have the potential to improve patient outcomes.

Quality indicators (QIs) are increasingly used to measure the quality of medical care. They provide an opportunity to quantify geographic variation, and identify areas where quality improvement interventions are needed.7 QIs may serve as a means of closing the second translational gap between evidence and practice and facilitate a unified approach to the appraisal of care using clinical registries.8 While a few individual indicators for cardiac devices have been developed by the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services,9–11 we are not aware of any published set of QIs for cardiac pacing. This is in contrast to sets of QIs by the ESC,12,13 and other professional societies.14,15 Therefore, the ESC established the Working Group for cardiac pacing QIs to work on the development of indicators of care quality for cardiac pacing in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and in parallel with the writing of the 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. This was undertaken under the auspice of the Clinical Practice Guideline Quality Indicator Committee of the ESC. This article describes the process by which the ESC QIs for cardiac pacing were developed and provide their measurement specifications.

Methods

The methodology by which the ESC develops QIs for the quantification of cardiovascular care and outcomes has been published.16 In brief, the methodology involves (i) the identification of key domains of care by constructing a conceptual framework of the patients’ management, (ii) the development of candidate QIs by conducting a systematic review of the literature, (iii) the selection of the final set of QIs using a modified-Delphi method, and (iv) the evaluation of the feasibility of the developed QIs.16 The term QI is used here to describe a discreet clinical situation in which a process of care is, or is not, recommended to allow specific measurements of performance. QIs can relate to the structure, process or outcomes of care, and include main and secondary indicators. The main indicators are those that have higher validity and feasibility by the Working Group members and thus may be used for measurement across regions and over time. Both the main and secondary QIs may be used for local quality improvement activities.16

Members of the Working Group

The Working Group comprised members of the Task Force of the 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy, members of the ESC Quality Indicator Committee, nominees from EHRA and the ESC Patient Forum, as well as international experts in cardiac devices. In total, 25 members from 13 countries participated in the Working Group, and attended a series of virtual meetings between November 2020 and March 2021.

Target population

The Working Group defined the ‘target population’ for the developed QIs as patients for whom a decision has been made to implant a cardiac pacemaker for bradyarrhythmia indication in accordance with the 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy.1 As such, patients with an indication for an implantable defibrillator and those undergoing device therapy for heart failure have been excluded. In addition, the definition used for the ‘target population’ excluded patients with undiagnosed bradyarrhythmia—thereby simplifying the operationalization of quality assessment when the QIs are established.

The Working Group defined, for each process QI, a denominator which describes the patient group eligible for the measurement, a numerator which outlines the criteria by which the QI is accomplished, a measurement period which specifies the time point at which the quality assessment is taking place, and a measurement duration which is the time frame needed for enough cases to be collected in order to accumulate meaningful data. For structural QIs, only numerator definitions were provided because these are binary (yes, no) measurements.12

Literature review

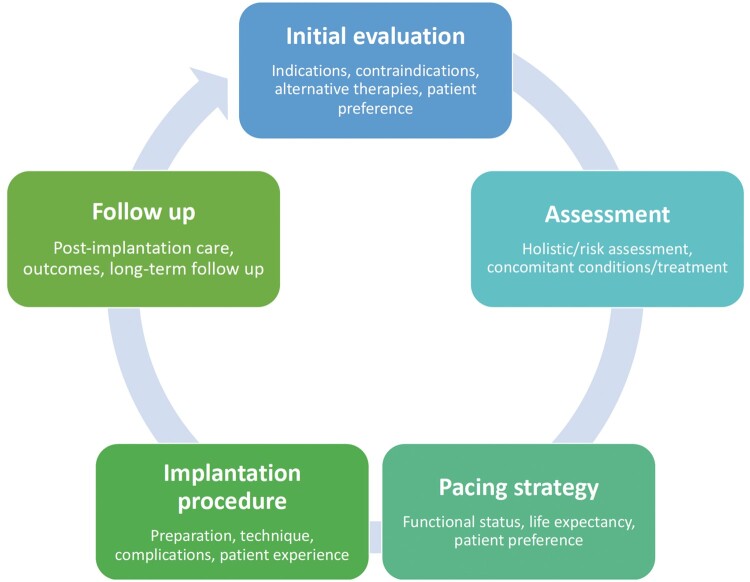

During the initial phases of the development process, the Working Group agreed on the specifications for the literature review and on the key domains of cardiac pacing care. These domains were identified by constructing a conceptual illustration of the care provision pathway, which formed the framework for the development of the QIs (Figure 1).16 In addition, there was an agreement between the Working Group members on patient-related outcome measures as an important domain of care for cardiac pacing. As such, patient-reported outcome measures, including the assessment of health-related quality of life using various tools were obtained from the literature.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of cardiac pacing patient journey.

We conducted a literature search of articles pertinent to cardiac pacing including publications from clinical registries,3,17 international guidelines,18,19 as well as the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services indicators,9–11 and societal recommendations.20 The literature review aimed to identify structural components or processes of cardiac pacing care that have a strong association with favourable patients’ outcomes, while the goal of the Clinical Practice Guidelines review was to assess the suitability of the class I and class III recommendations against the ESC criteria for QIs (Supplementary material online, Table S1).

Furthermore, and to help identify the optimal pacing strategy for patients requiring a de novo permanent pacemaker for bradyarrhythmia, a systematic review and a meta-analysis were conducted simultaneously with the development of this document.21 This review highlighted that whilst novel pacing modalities such as His-bundle pacing and left bundle branch area pacing maintain physiological ventricular activation, the published studies to date are limited by their observational design or sample size and that comparative studies are needed to understand the impact of such pacing strategies on clinical outcomes.21

Consensus development

Modified Delphi process

The candidate QIs derived from the aforementioned process were evaluated using the modified Delphi method.16 The ESC criteria for QI development (Supplementary material online, Table S1) were shared with the Working Group members prior to the voting in order to standardize the selection process. All candidate QIs were graded for validity and feasibility by each panellist via an online questionnaire using a 9-point ordinal scale.16 Two rounds in total were conducted, with teleconferences in between to discuss the results of the vote and address any concerns or ambiguities.

Analysing voting results

A 9-point ordinal scale was used in the Delphi rounds. Ratings of 1 to 3 were interpreted as the QI was not valid/feasible, with ratings of 4 to 6 meaning that the QI was of an uncertain validity/feasibility and ratings of 7 to 9 that the QI was valid/feasible. For each candidate QI, the median and the mean deviation from the median were calculated to provide the central tendency and the dispersion of votes. Cut-offs for inclusion were similar to those reported in the literature.22 Thus, candidate QIs with median scores ≥7 for validity, ≥4 for feasibility, and with minimal inter-rater variation were included in the final set of QIs. We defined those QIs fulfilling the above numerical threshold for inclusion following the first voting round as the main QIs, while those fulfilling the numerical threshold for inclusion after a second round of voting as secondary QIs (Supplementary material online).

Results

Domains of care

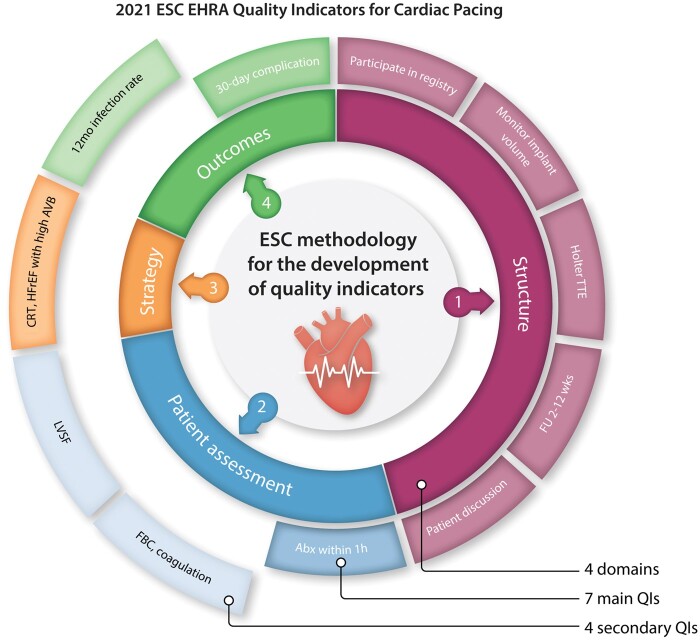

Four domains of cardiac pacing care were identified by the Working Group. These included: (i) structural framework domain, which evaluates the characteristics of the centres providing a cardiac pacing service, (ii) patient assessment domain, which evaluates the appropriateness of the investigations performed prior to cardiac pacing implantation, (iii) pacing strategy domain, which evaluates the selection of the pacing method, and (iv) outcomes domain, which captures the clinical outcomes of cardiac pacing (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Domains of cardiac pacing care, with the corresponding QIs for each domain. Abx, antibiotics; AVB, atrioventricular block; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; ECG, electrocardiogram; EHRA, European Heart Rhythm Association; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; FBC, full blood count; F/U, follow-up; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LVSF, left ventricle systolic function; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

Quality indicators

The literature search retrieved a total of 25 candidate QIs, which were included in the first round of the voting process. Of those and based on the parameters above, 12 (48%) were excluded and 7 (28%) were included as main QIs. The remaining 6 QIs were deemed inconclusive and were, therefore, carried to a second voting round, following which 4 (67%) were included as secondary QIs. Of the 11 selected QIs, 5 (46%) related to the structural framework domain, 3 (27%) to the patient assessment domain, 1 (9%) to the pacing strategy domain, and 2 (18%) to the outcome domain (Figure 2). According to the voting results, the proposed patient-reported outcome measures did not meet the inclusion criteria and so none were selected for the final set of indicators.

Domain 1: Structural framework

Structural QIs evaluate the characteristics of the centres providing cardiac pacing service, and play a role in quality assessment at the institutional level. The association between certain aspects of cardiac devices patient care and outcomes has been facilitated by well-conducted registries at the national level.4 As such, the participation in at least one registry for cardiac pacing is an indicator of care quality (Main 1.1). In addition, data from observational studies have shown an inverse association between the centre procedural volume and complication rates and thus the monitoring and reporting of the centre-specific annual rate of cardiac pacing implantation is recommended (Main 1.2) (Table 1).4,23

Table 1.

The 2021 ESC QIs for patients undergoing cardiac pacemaker implantation

| Domain 1. Structural framework |

| Main (1.1): Centres providing CIED service should participate in at least one CIEDa registry.b |

| Numerator: Number of centres participating in at least one CIED registry. |

| Main (1.2): Centres providing CIED service should monitor and report the volume of procedures performed by individual operators on annual basis.b |

| Numerator: Number of centres monitoring and reporting the volume of procedures performed by individual operators. |

| Main (1.3): Centres providing CIED service should have available resources (ambulatory ECG monitoring, echocardiogram) to stratify patients according to their risk for ventricular arrhythmias.b |

| Numerator: Number of centres with an available ambulatory ECG and echocardiogram service. |

| Main (1.4): Centres providing CIED service should have established protocols to follow-up patients within 2–12 weeks following implantation.b |

| Numerator: Number of centres that have an established protocols to follow-up patients within 2–12 weeks following CIED implantation. |

| Main (1.5): Centres providing CIED service should have a pre-procedural checklist to ensure discussion with patient regarding risks, benefits, and alternative treatment options.b |

| Numerator: Number of centres that have a checklist to ensure discussion with patient regarding risks, benefits, and alternative treatment options prior to CIED implantation. |

| Domain 2. Patient assessment |

| Main (2): Proportion of patients considered for CIED implantation who receive prophylactic antibiotics 1 h before their procedure.c |

|

Numerator: Number of patients who receive antibiotics 1 h before their CIED implantation.

Denominator: Number of patients who have CIED implantation. |

| Secondary (2.1): Proportion of patients considered for CIED implantation who have their full blood count and coagulation profile checked prior to the procedure.c |

|

Numerator: Number of patients who have their full blood count and coagulation profile checked prior to CIED implantation.

Denominator: Number of patients who have CIED implantation. |

| Secondary (2.2): Proportion of patients considered for CIED implantation who have an imaging evaluation of their LV structure and systolic function prior to the procedure.c |

|

Numerator: Number of patients who have an imaging evaluation of their LV structure and systolic function prior to CIED implantation.

Denominator: Number of patients who have CIED implantation. |

| Domain 3. Pacing strategy |

| Secondary (3): Proportion of patients with an indication for ventricular pacing and high degree AV block who have HFrEF and undergo CRT.c |

|

Numerator: Number of patients with an indication for ventricular pacing and high degree AV block who have HFrEF and undergo CRT implantation.

Denominator: Number of patients with an indication for ventricular pacing and high degree AV block who have HFrEF and undergo CIED implantation. |

| Domain 4. Outcomes |

| Main (4): Annual rate of procedural complications 30 days following CIED implantation.d |

|

Numerator: Number of patients who develop one or more of the procedural complicationse within 30 days from their CIED implantations

Denominator: Number of patients who have CIED implantation. |

| Secondary (4): Annual rates of CIED-related infections up to 1 year following CIED implantation, replacement, or revision.d |

|

Numerator: Number of patients who develop CIED-related infections up to 1 year following CIED implantation, replacement, or revision.

Denominator: Number of patients who have CIED implantation, replacement, or revision. |

AV, atrioventricular; CIED, cardiovascular implantable electronic device; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; LV, left ventricular; QIs, quality indicators.

CIED here refer to cardiac pacemakers.

Structural QIs are binary measurements (Yes/No), and, thus, only numerator is defined.

Measurement period: encounter, measurement duration: annually.

Annual measurements.

Procedural complications are defined as CIED-related bleeding, pneumothorax, cardiac perforation, tamponade, pocket haematoma, lead displacement (all requiring intervention), or infection.

The other three indicators in the structural domain include the availability of resources for the risk-stratification and clinical characterization of patients undergoing cardiac pacing, such as ambulatory rhythm monitoring and echocardiography (Main 1.3),20 of follow-up protocols within 2–12 weeks after device implantation (Main 1.4), and the presence of pre-procedural checklists documenting a discussion with patients regarding the risks and benefits of device implantation and alternative treatment options prior to implantation (Main 1.5) (Table 1).

Domain 2: Patient assessment

Patient evaluation and preparation prior to cardiac pacing implantation reduces the risks of complications associated with the procedure and guides the selection of an appropriate pacing strategy.24,25 Evidence favours the efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics in reducing the rates of cardiac device-related infections (Main 2).26,27 The performance of basic blood tests, such as full blood count and coagulation profile may help identify patients with high risk of periprocedural complications (Secondary 2.1),25 while the evaluation of the left ventricular structure and function prior to cardiac pacing helps determine the most appropriate device for the patient (Secondary 2.2) (Table 1).24

Domain 3: Pacing strategy

For patients with heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction who have an indication for ventricular pacing and a high degree atrioventricular block, biventricular pacing with cardiac synchronization therapy has been shown to improve clinical outcomes over right ventricular pacing. Thus, the proportion of patients who receive cardiac synchronization therapy among those eligible was selected as a QI (Secondary 3) (Table 1).24

Domain 4: Outcomes

The measurement of outcomes following cardiac pacing helps benchmark performance, monitor temporal trends of adverse events and study the efficacy of quality improvement interventions. As such, complications occurring within 30 days following device implantation is delegated an indicator of care quality (Main 4). However, infections related to cardiac pacing may be delayed beyond the first month following implantation.6 Accordingly, infections up to 1 year after device insertion is also regarded as a measure of care quality (Secondary 4) (Table 1).

Patient perspective

Patient-reported outcome measures reflect the patients’ perspective of the impact of the condition and its treatment on their lives and are important determinants of the patients’ perceived quality and outcomes of care. Among the different categories of patient-reported outcome measures, patients’ health-related quality of life is of interest because it is multi-dimensional and allows the exploration of patients’ physical, emotional, and social well-being.28 While disease-specific tools exist for a number of cardiovascular disease conditions, including atrial fibrillation, arrhythmia, and heart failure, these capture limited data specific to cardiac devices implantation.29 As such, the Delphi voting reached no consensus as to the inclusion of patient-reported outcome measures in the final set of QIs with reason being lack of specificity and limited evidence to support their use.

Whereas there are common outcomes that matter to the majority of patients, individual patients may have specific outcomes of a higher importance to them based on a number of factors, such as their age or sex. For instance, a physically active patient might be concerned about restrictions of their arm and shoulder movement which may affect the ability to perform certain activities. The appearance of the scar and/or the implanted device may be more of a worry for women than men, and elderly patients might have concerns about complications related to device implantation and therapies. As such, attention is needed when designing patient-reported outcome measures to capture not only what matters to the ‘average’ patient but also to individual patient’s values.

Furthermore, it should be noted that patients’ perceptions, particularly in cardiac pacing, may change over time. For example, the implanted device implications on patients’ lives may differ according to changes in their overall health, underlying condition, and response to treatment.30 Therefore, the patient representatives within the Working Group felt that it was important to capture the trajectories of patients’ health-related quality of life following cardiac device implantation, and proposed a non-exhaustive list of potential areas for pacing QIs based on personal experience and exchanges with other patients (Supplementary material online, Table S2).

Discussion

In this document, we provide a suite of seven main and four secondary QIs that transcend four patient journey domains and may be used in the evaluation of cardiac pacing care and outcomes. The QIs were developed though a standardized methodology,16 which has been used for the development of feasible and valid QIs for other cardiovascular conditions,12 and as a joint effort between the Task Force of the 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy, EHRA, the ESC Patient Forum, and international experts in cardiac devices under the remit of the ESC Clinical Practice Guideline Quality Indicator Committee. The participation of stakeholders from 13 countries, including patients, and the co-development of these QIs with the 2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy, have enabled the provision of specific, measurable, and relevant QIs for cardiac pacing care.

The growing number of cardiac pacemaker implantations across Europe, and the variation in practice observed in clinical registries, has created the necessity to develop standardized indicators for cardiac pacing quality of care and outcomes. Although the Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services have developed individual measures for cardiac devices, these are limited to specific domains of patients care, such as follow-up following implantation,10 infection rates,9 and complications after defibrillator implantation.11 Here, we propose a suite of QIs that provides a framework that encompasses a wide and comprehensive perspective of cardiac pacing care, including structural, process and outcome measures.

It is hoped that by providing QIs for cardiac pacing that are endorsed by professional societies and co-developed with patients, a systematic and international approach to the assessment of care and outcomes for patients undergoing cardiac pacemakers may be established. Such a system may be used by the professional societies, healthcare authorities or hospitals to identify and address unwanted variation and monitor patterns of care. Consequently, policies and quality improvement activities may be developed to facilitate continuous benchmarking of performance over time and across regions, and the subsequent behaviour change needed to improve care delivery. The set of QIs that were developed may provide the basis for applying the process of Health Technology Assessment to the setting of cardiac pacing.31

The four domains of cardiac pacing care for which the QIs were developed cover broad spectrum of patient journey and may provide meaningful interpretation of care quality. We did not include QIs relevant to procedural technique, such as venous access and pacing site, in this document because these aspects of cardiac pacing care are covered in a recent EHRA consensus document on optimal implantation technique for pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.32 In addition, QIs pertinent to novel pacing modalities such as His-bundle pacing and left bundle branch area pacing have not been selected by the Working Group members. This may be explained by the limitations of the existing evidence supporting such modalities.21

Furthermore, the Working Group acknowledges that other domains may also be as important. This may include patient-reported outcome measures and the assessment of health-related quality of life in patients undergoing cardiac pacemaker implantation. While no patient-reported outcome measures were selected in the final set of QIs, the Working Group envisages that there is a need to develop and validate patient-reported measures which are specific to the implant of cardiac pacemakers.

The methodology used for the development of these QIs has limitations. We relied on expert opinion to arrive at the final set of QIs. Different panel of experts may have selected a different set of QIs, but the use of the modified Delphi method to obtain group opinion, and the involvement of patients and registry experts have provided wide perspective and standardization to the selection process. Furthermore, the application of a structured criteria, namely the ESC criteria for QI development, in selecting the QIs and guiding the voting process improved the objectivity in building consensus amongst the Working Group members.

Another limitation is the numerical thresholds used for the inclusion of the QIs, and the selection between main and secondary ones. Notwithstanding that these thresholds have been validated,22 and recommended by the ESC methodology,16 one may anticipate that different cut-offs may have retrieved different indicators. However, having a structured method to interpret the experts’ opinion provided standardization to the process and consistency across the various voting rounds. Given the number of the Working Group members and the narrow scale of the voting, the accepted level of inter-rater variation may be perceived too inclusive. However, this approach was adopted to reduce the likelihood of excluding important QIs which may be relevant to practice.

The developed QIs are intended to drive comprehensive patient assessments and drive quality improvement, and, thus, should not be considered in isolation. Furthermore, regular updates are needed for these QIs and/or to their specifications when ‘real-world’ and feasibility data become available. It is hoped that the developed set of QIs would be implemented in, and facilitate the development of, data collection efforts aiming to assess and improve the quality of cardiac pacing care. For instance, the European Unified Registries on Heart care Evaluation and Randomized Trials (EuroHeart) project33 may favour the implementation of methodologically developed QIs for future cardiac device registries in Europe, which this statement uniquely provides.

Conclusion

Using the ESC methodology for QI development, a set of QIs for cardiac pacing have been developed across four key domains of care. These QIs provide the means to systematically measure the quality of care for patients undergoing cardiac pacemakers and capture care outcomes through their implementation in daily practice and clinical registries.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Conflict of interest: H.B. reports speaker fees/consultancy from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Medtronic and Microport. G.B. reports speaker’s fees of small amount form Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston and Medtronic. P.D. reportsed grants and honoraria from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Abbott and Microport CRM. M.G. reportsed consultant and Clinical trial support: Boston Scientific and Medtronic. Clinical Trial Steering Committee: Abbott, Boston Scientific, EBR, Medtronic. C. P. G reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Bayer, grants from BMS, personal fees from Boehrinher-Ingelheim, personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, personal fees from Vifor Pharma, grants from Abbott, personal fees from Menarini, personal fees from Wondr Medical, personal fees from Raisio Group, grants from British Heart Foundation, grants from NIHR, grants for Horizon 2020, personal fees from Oxford University Press, outside the submitted work. J.C.N. is supported by grants from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF16OC0018658 and NNF17OC0029148). J.M.T. reports consultancy of Boston Scientific, Abbott and Medtronic. K.V. reports consultancy, grants and honoraria from Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Suleman Aktaa, Leeds Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; Leeds Institute for Data Analytics and Leeds Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK; Department of Cardiology, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK.

Amr Abdin, Internal Medicine Clinic III, Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Saarland University Hospital, Homburg/Saar, Germany.

Elena Arbelo, Arrhythmia Section, Cardiology Department, Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Institut d'Investigacións Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

Haran Burri, Cardiology Department, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland.

Kevin Vernooy, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Research Institute Maastricht (CARIM), Maastricht University Medical Center (MUMC), Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Carina Blomström-Lundqvist, Department of Medical Science and Cardiology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

Giuseppe Boriani, Cardiology Division, Department of Biomedical, Metabolic and Neural Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Policlinico di Modena, Modena, Italy.

Pascal Defaye, Department of Cardiology, Arrhythmias Unit, University Hospital Grenoble Alps and Grenoble Alps University, Grenoble, France.

Jean-Claude Deharo, Aix Marseille Univ, INSERM, INRAE, C2VN, Marseille, France; Service de Cardiologie, Hôpital de la Timone, APHM, Marseille, France.

Inga Drossart, Drossart (Belguim), ESC Patient Forum, Sophia Antipolis.

Dan Foldager, Foldager(Denmark), ESC Patient Forum, Sophia Antipolis, France.

Michael R Gold, Division of Cardiology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

Jens Brock Johansen, Department of Cardiology, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark.

Francisco Leyva, Department of Cardiology, Aston Medical School, Aston University, Birmingham, UK; Department of Cardiology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, UK.

Cecilia Linde, Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Solna, Sweden; Department of Cardiology, Karolinska University Hospital, Solna, Sweden.

Yoav Michowitz, Cardiology Department, Shaare Zedek Hospital, Affiliated to the Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel.

Mads Brix Kronborg, Department of Cardiology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; Department of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

David Slotwiner, Cardiology Division, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Torkel Steen, Centre for Pacemakers and ICDs, Oslo University Hospital Ullevaal, Oslo, Norway.

José Maria Tolosana, Arrhythmia Section, Cardiology Department, Hospital Clínic, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Institut d'Investigacións Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain.

Stylianos Tzeis, Cardiology Department, Mitera General Hospital, Hygeia Group, Athens, Greece.

Niraj Varma, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Michael Glikson, Cardiology Department, Shaare Zedek Hospital, Affiliated to the Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel.

Jens Cosedis Nielsen, Department of Cardiology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; Department of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

Chris P Gale, Leeds Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; Leeds Institute for Data Analytics and Leeds Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK; Department of Cardiology, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK.

References

- 1. Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, Michowitz Y, Auricchio A, Barbash IM et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace 2022;24:71--164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bradshaw PJ, Stobie P, Knuiman MW, Briffa TG, Hobbs MS. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of cardiac pacemaker insertions in an ageing population. Open Heart 2014;1:e000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raatikainen MJP, Arnar DO, Merkely B, Nielsen JC, Hindricks G, Heidbuchel H et al. A decade of information on the use of cardiac implantable electronic devices and interventional electrophysiological procedures in the European Society of Cardiology Countries: 2017 report from the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 2017;19:ii1–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kirkfeldt RE, Johansen JB, Nohr EA, Jørgensen OD, Nielsen JC. Complications after cardiac implantable electronic device implantations: an analysis of a complete, nationwide cohort in Denmark. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1186–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale CP, Torbica A, Lettino M, Petersen SE et al. ; European Society of Cardiology. European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2019. Eur Heart J 2020;41:12–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olsen T, Jørgensen OD, Nielsen JC, Thøgersen AM, Philbert BT, Johansen JB. Incidence of device-related infection in 97 750 patients: clinical data from the complete Danish device-cohort (1982-2018). Eur Heart J 2019;40:1862–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bebb O, Hall M, Fox KAA, Dondo TB, Timmis A, Bueno H et al. Performance of hospitals according to the ESC ACCA quality indicators and 30-day mortality for acute myocardial infarction: national cohort study using the United Kingdom Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) register. Eur Heart J 2017;38:974–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaide Services Measures Inventory Tool. https://cmit.cms.gov/CMIT_public/ViewMeasure?MeasureId=2389 (17 December 2020, date last accessed).

- 10.Centers for Medicare and Medicaide Services Measures Inventory Tool. https://cmit.cms.gov/CMIT_public/ViewMeasure?MeasureId=3218 (17 December 2020, date last accessed).

- 11.Centers for Medicare and Medicaide Services Measures Inventory Tool. https://cmit.cms.gov/CMIT_public/ViewMeasure?MeasureId=1979 (17 December 2020, date last accessed).

- 12. Schiele F, Aktaa S, Rossello X, Ahrens I, Claeys MJ, Collet J-P et al. 2020 update of the quality indicators for acute myocardial infarction: a position paper of the Association for Acute Cardiovascular Care: the study group for quality indicators from the ACVC and the NSTE-ACS guideline group. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2021;10:224–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arbelo E, Aktaa S, Bollmann A, D'Avila A, Drossart I, Dwight J et al. Quality indicators for the care and outcomes of adults with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2020;23:494–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ACC/AHA Clinical Performance and Quality Measures. https://www.onlinejacc.org/collection/performance-measures (04 April 2021, date last accessed).

- 15.CCS Data Definitions & Quality Indicators. https://ccs.ca/ccs-data-definitions-quality-indicators/ (04 April 2021, date last accessed).

- 16. Aktaa S, Batra G, Wallentin L, Baigent C, Erlinge D, James S et al. European Society of Cardiology methodology for the development of quality indicators for the quantification of cardiovascular care and outcomes. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2020. https://academic.oup.com/ehjqcco/advance-article/doi/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa069/5897413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang S, Gaiser S, Kolominsky-Rabas PL; National Leading-Edge Cluster Medical Technologies “Medical Valley EMN”. Cardiac implant registries 2006-2016: a systematic review and summary of global experiences. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Barrett C, Edgerton JR, Ellenbogen KA, Gold MR et al. ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2019;140:e382–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron-Esquivias G, Bordachar P, Boriani G, Breithardt OA, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the task force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Europace 2013;15:1070–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haines DE, Beheiry S, Akar JG, Baker JL, Beinborn D, Beshai JF et al. Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on electrophysiology laboratory standards: process, protocols, equipment, personnel, and safety. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:e9–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abdin A, Aktaa S, Vukadinović D, Arbelo E, Burri H, Glikson M et al. Outcomes of conduction system pacing compared to right ventricular pacing as a primary strategy for treating bradyarrhythmia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Cardiol 2021; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, Keesey J, Klein DJ, Adams JL et al. The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1515–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nowak B, Tasche K, Barnewold L, Heller G, Schmidt B, Bordignon S et al. Association between hospital procedure volume and early complications after pacemaker implantation: results from a large, unselected, contemporary cohort of the German nationwide obligatory external quality assurance programme. Europace 2015;17:787–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curtis AB, Worley SJ, Adamson PB, Chung ES, Niazi I, Sherfesee L et al. ; Biventricular versus Right Ventricular Pacing in Heart Failure Patients with Atrioventricular Block (BLOCK HF) Trial Investigators. Biventricular pacing for atrioventricular block and systolic dysfunction. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1585–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klug D, Balde M, Pavin D, Hidden-Lucet F, Clementy J, Sadoul N et al. ; PEOPLE Study Group. Risk factors related to infections of implanted pacemakers and cardioverter-defibrillators: results of a large prospective study. Circulation 2007;116:1349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Polyzos KA, Konstantelias AA, Falagas ME. Risk factors for cardiac implantable electronic device infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2015;17:767–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Traykov V, Erba PA, Burri H, Nielsen JC, Bongiorni MG et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus document on how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections-endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Europace 2020;22:515–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cella DH, Hahn EA, Jensen SE, Butt Z, Nowinski CJ, Rothrock N et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Performance Measurement. Research Triangle Park (NC): RTI Press; 2015. Types of Patient-Reported Outcomes. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424381/. [PubMed]

- 29. Algurén B, Coenen M, Malm D, Fridlund B, Mårtensson J, Årestedt K; Collaboration and Exchange in Swedish cardiovascular caring Academic Research (CESAR) group. A scoping review and mapping exercise comparing the content of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) across heart disease-specific scales. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2020;4:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Udo EO, van Hemel NM, Zuithoff NPA, Nijboer H, Taks W, Doevendans PA et al. Long term quality-of-life in patients with bradycardia pacemaker implantation. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:2159–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boriani G, Maniadakis N, Auricchio A, Müller-Riemenschneider F, Fattore G, Leyva F et al. Health technology assessment in interventional electrophysiology and device therapy: a position paper of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1869–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burri H, Starck C, Auricchio A, Biffi M, Burri M, D’Avila A et al. EHRA expert consensus statement and practical guide on optimal implantation technique for conventional pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Latin-American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). Europace 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wallentin L, Gale CP, Maggioni A, Bardinet I, Casadei B. EuroHeart: European Unified Registries on heart care evaluation and randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2745–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.